Abstract

Background

The green speckled lentil seed (Lens culinaris) lectin (GSLL) exhibits hemagglutinating activity, and possesses some properties distinct from those of other lentil lectins (e.g., molecular size, biological activities) that deserve further investigation. This study aims to investigate the basic properties (e.g., molecular size, amino acid sequence, sugar specificity) and biological activities (e.g., antiproliferative activity) of GSLL.

Methods

GSLL was purified by successive fractionation on SP-Sepharose, Affi-gel blue gel, Mono Q, and Superdex 75. The biochemical properties of GSLL were investigated by SDS-PAGE, mass spectrometry, N-terminal amino acid sequencing, and sugar inhibition tests. For the biological activities, purified lyophilized GSLL was sterilized, adjusted to concentrations from 1 to 0 mg/mL (by twofold serial dilution) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with fetal bovine serum, and examined by using the MTT assay, flow cytometry, and western blotting after treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma CNE1 and CNE2 cell lines with the lectin.

Results

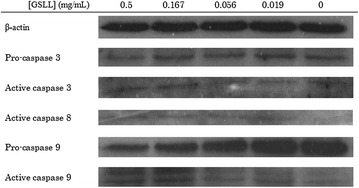

GSLL appeared as a 21-kDa band in non-reducing SDS-PAGE. It was composed of two subunits with molecular sizes of 17 and ~4 kDa. It exhibited specificity in binding to glucose and mannose, as well as glucosides and mannosides. Mass spectrometry and N-terminal amino acid sequencing revealed similarity of GSLL to L. culinaris lectin (LcL), especially higher coverage of the β-chain of LcL. A 48-h treatment with GSLL exerted antiproliferative effects on nasopharyngeal carcinoma CNE1 and CNE2 cell lines with significant inhibition at 0.125 mg/mL (P < 0.001) and 1 mg/mL (P = 0.004), respectively, and these effects were attenuated in the presence of glucose and mannose. GSLL induced apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma CNE1 cells, with detectable phosphatidylserine externalization, mitochondrial depolarization, and cell cycle arrest. Western blot analysis suggested that GSLL triggered the extrinsic apoptotic pathway involving caspase 3, 8, and 9 in CNE1 cells.

Conclusion

GSLL possessed some different properties from LcL (e.g., lower pI), and increased caspase 3, 8, and 9 activity in CNE1 cells.

Background

Lentil (Lens culinaris) seeds contain high contents of proteins (~25 % dry weight) and minerals (Zn, Fe, Ca, Mn, etc.) [1, 2]. They are also rich in dietary fiber, which helps the digestive tract to function under good conditions [3], have high contents of folate and magnesium that reduce the risk of coronary heart disease [4], and possess high levels of iron [5]. In Chinese medicine, lentil seeds benefit the spleen (pi) and stomach (wei), and relieve dampness (shi) of the body [6, 7].

Lentil seeds contain a carbohydrate-binding protein, L. culinaris lectin (LcL) or hemagglutinin (LcH) [8]. The sequence and structure of LcLs have been elucidated [9], and they bind to glucose, mannose, and some glucose- and mannose-containing sugars, as well as to α-d-mannopyranosyl and α-d-glucopyranosyl residues of glycoproteins and glycolipids [10]. LcLs can bind to specific carbohydrate groups of glycoproteins on cell surfaces, thus allowing studies on differences in the levels of glycoproteins in different cell types [11, 12]. They are also used in affinity chromatography for detection of glucose- and mannose-containing biomarkers, e.g., LcLs can bind to α-fetoprotein in the blood for diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma [13, 14].

Lentils are differentiated into many different cultivars worldwide, such as the green speckled lentil in the United States. Although not manufactured in bulk quantities, the product of edible dry green speckled lentil seeds can be found in a number of supermarkets. Similar to other lentil seeds, green speckled lentil seeds contained a lectin that exhibited hemagglutinating activity [15]. Although LcLs have been well studied, little information is available on lentil lectins from other cultivars. Different cultivars of lentil seeds may generate lectins with variable activities. For example, the lectin from the extralong autumn purple bean cultivar (Phaseolus vulgaris) had prominent antiproliferative activity on hepatoma HepG2 cells [16]. Meanwhile, the lectin from the brown kidney bean cultivar (P. vulgaris) inhibited breast cancer MCF7 cells and nasopharyngeal carcinoma CNE1 cells more strongly than it inhibited HepG2 cells [17], and their counterpart from an Indian cultivar (P. vulgaris) was devoid of anticancer activity [18].

This study aims to investigate the basic properties (e.g., molecular size, amino acid sequence, sugar specificity) and biological activities (e.g., antiproliferative activity) of the green speckled lentil seed lectin (GSLL).

Methods

Purification

Green speckled lentil seeds were purchased from a local supermarket in Shatin, New Territories, Hong Kong. The seeds were authenticated using a DNA analysis method, which was carried out by Prof. Shiu-Ying Hu, Honorary Professor of Chinese Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. The seeds (80 g) were soaked in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.6) overnight, homogenized in a blender, and centrifuged twice at 30,000×g and 4 °C for 25 min in an Avanti J-E High Speed centrifuge (Beckman Coulter, USA). The 800-mL supernatant obtained constituted a crude extract of the seeds. This extract was loaded onto an SP-Sepharose column (Code: 17-0729-04; GE Healthcare, USA) (5 cm × 15 cm) previously pre-equilibrated with the same buffer. The unbound fraction containing GSLL was collected and loaded onto an Affi-gel blue gel column (Code: 1537301; Bio-Rad, USA) (5 cm × 15 cm). The unbound materials were removed by washing with the buffer. The adsorbed materials were eluted with 1 M NaCl in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.6) and collected as the bound fraction. The bound fraction was dialyzed against double-distilled water, and lyophilized into powder form.

The powder was resuspended into a 15 mg/mL protein solution in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.6), and injected into a Mono Q 5/50 GL column (Code: 17-5166-01; GE Healthcare) for fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) with an AKTA purifier (Code: 28-4062-64; GE Healthcare). An increasing NaCl concentration was utilized to elute the column. Fractions of the first adsorbed peak corresponding to the lectin were collected, dialyzed, and lyophilized.

The powder was resuspended into a 5 mg/mL protein solution in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.6), and loaded onto a Superdex 75 10/300 GL column (Code: 17-5174-01; GE Healthcare) for size-exclusion FPLC with the AKTA purifier. The last peak eluted at the 37th minute contained purified GSLL [16].

Biochemical property tests

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

Loading buffer with (for reducing SDS-PAGE) or without (for non-reducing SDS-PAGE) β-mercaptoethanol was added to the fractions obtained at different steps during the purification of GSLL. The samples were loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel (15 % running gel; 5 % stacking gel), and subjected to SDS-PAGE at a constant voltage of 120 V for 70 min. The gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue for 1 h, and destained with 10 % acetic acid overnight [18].

Assay of hemagglutinating activity

Using a Corning® Costar® 96-Well U-plate (Code: CLS3799; Sigma-Aldrich), twofold serial dilutions of a 50-µL protein sample in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were prepared. The same volume of 2 % rabbit red blood cell suspension was added to the wells. After approximately 1 h, the red blood cells in the control (without protein sample) sank to the bottom of the well and appeared as a red spot. The presence of proteins with hemagglutinating activity would cause the cells to clump together and form a plaque [17].

Carbohydrate specificity test

Twofold serial dilutions of a 50-µL protein sample in PBS were prepared in a 96-well U-plate, and different carbohydrate solutions (glucose, mannose, galactose, glucosamine, maltose, rhamnose, arabinose, N-acetylgalactosamine, α-methyl-d-glucoside, α-methyl-pyranoside, raffinose, mannitol, xylitol) were added. The same volume of 2 % rabbit red blood cell suspension was added to the wells. A reduction in hemagglutinating activity indicated that the carbohydrate was specific in its interaction with the lectin, resulting in competitive inhibition of lectin binding with the red blood cells [17].

Mass spectrometry

Purified lectin was subjected to SDS-PAGE in a polyacrylamide gel (15 % running gel; 5 % stacking gel) at a constant voltage of 120 V for 70 min. The gel was stained, and the area containing the protein band was cut into small pieces. The gel was destained, dehydrated in acetonitrile, and air-dried. A minimal amount of trypsin was added to the gel and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h to allow digestion. The solution containing the tryptic fragments was transferred to a tube, and sent to the laboratory in the Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong, for mass spectrometry analysis according to a previously described procedure [19].

N-terminal amino acid sequencing

Purified lectin was subjected to SDS-PAGE in a polyacrylamide gel (15 % running gel; 5 % stacking gel) at a constant voltage of 120 V for 70 min, and then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using a Trans-Blot® SD Semi-Dry Electrophoretic Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad) at a constant voltage of 15 V for 40 min. The membrane was sent to the central laboratory of Beijing Agricultural University, Beijing, for N-terminal amino acid sequencing using a previously described procedure [20].

Comparison of amino acid sequences

An NCBI BLAST (Standard Protein BLAST: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastp&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome) analysis was conducted using the results from the mass spectrometry and N-terminal amino acid sequencing to search for known proteins with similarity to GSLL. The proteins showing the highest scores (most closely related to GSLL) were marked, and the differences in their amino acid sequences were identified.

Biological activity tests

MTT assay

Human nasopharyngeal carcinoma CNE1 and CNE2 cells were purchased from the Sun Yat-sen University of Medicinal Sciences (China). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10 % fetal bovine serum and 100 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin, and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under 5 % CO2. The cells were seeded onto Corning® Costar® 96-Well plates (Code: CLS3595; Sigma-Aldrich) overnight. Different concentrations of GSLL were added to the cells and incubated at 37 °C for 24, 48, or 72 h. The effects of addition of 62.5 mM glucose or mannose on the GSLL treatment of CNE1 cells were examined to investigate the inhibitory effects of the carbohydrates on the action of GSLL on CNE1 cells. Briefly, after the wells were washed with PBS, 25 µL of MTT (5 mg/mL) in PBS was added and incubated for 4 h. Next, 150 µL of DMSO was added to the wells, and the optical density at 580 nm was recorded with a SpectraMax i3 Multi-mode Plate Reader (Molecular Devices, USA). The IC50 values for GSLL treatment of the cells were determined as the GSLL concentrations causing 50 % inhibition of the cells.

Flow cytometry

CNE1 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates overnight. Different concentrations of GSLL were added to the cells and incubated for 48 h. The cells were then trypsinized and washed with PBS. For assessment of phosphatidylserine externalization, 250 µL of binding buffer containing 1.25 µL of Annexin V-FITC and 0.5 µL of propidium iodide (PI) was added to the cells, followed by incubation in the dark for 15 min. For assessment of mitochondrial depolarization, 250 µL of PBS containing 2.5 µg/mL JC-1 was added to the cells, and incubated in the dark for 15 min. For cell cycle analysis, the cells were fixed in 70 % ethanol at −20 °C for 2 h and washed with PBS, followed by addition of 250 µL PBS containing 5 µL of PI and incubation in the dark for 15 min. The cells were examined with a BD LSRFortessa™ Cell Analyzer (BD Biosciences, USA). The data were analyzed using BD FACSDiva 7.0 software (BD Biosciences).

Western blotting

CNE1 cells were seeded onto 90-mm petri dishes and treated with different concentrations of GSLL for 48 h. The cells were trypsinized, washed with PBS, and lysed with RIPA buffer on ice for 2 h. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 20,000×g and 4 °C for 30 min, and the supernatants were collected as the protein fractions. SDS-PAGE was performed, followed by semi-dry transfer onto a PVDF membrane using a Trans-Blot® SD Semi-Dry Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad) at a constant voltage of 15 V for 40 min. The PVDF membrane was blocked with 5 % milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1 % Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h, incubated with a primary antibody (1:1000 in 5 % milk in TBST) at 4 °C overnight, washed with TBST, and incubated with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-associated secondary antibody (1:1000 in 5 % milk in TBST) at room temperature for 2 h. Primary antibodies used included: Rabbit anti-caspase 3 antibody (Code: #9662; Cell Signaling); Rabbit anti-cleaved caspase 8 antibody (Code: #9496; Cell Signaling); Rabbit anti-caspase 9 antibody (Code: #9502; Cell Signaling). Secondary antibody used included HRP-linked anti-rabbit antibody (Code: #7074; Cell Signaling). The presence of the target proteins was visualized with an electrochemiluminescence detection system using an Amersham ECL Western Blotting Detection Kit (Code: RPN2018; GE Healthcare).

Statistical analysis

Cell culture experiments were performed three times. The percentage inhibition obtained in each trial, and the mean percentage inhibition and standard deviation of the three trials were obtained using Microsoft Office Excel 2003 (Microsoft, USA). P-values for each data point were calculated by a two-tailed Student’s t test using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., USA). Data points with P-values below 0.05 were determined as significant results.

Results

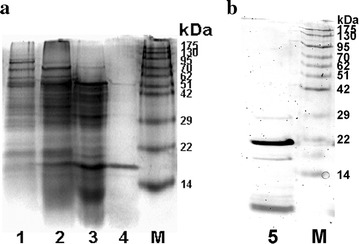

The current protocol used for purification of GSLL from green speckled lentil seeds comprised ion exchange chromatography (SP-Sepharose: cation exchanger; Mono Q: anion exchanger), affinity chromatography (Affi-gel blue gel), and size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 75). After the first two chromatographic steps (non-adsorption on SP-Sepharose and adsorption on Affi-gel blue gel), GSLL was purified by about 5.6-fold (Table 1). A major absorbance peak after this purification process was detected in the unbound fractions, and two peaks were detected in the bound fractions eluted with a gradient of increasing NaCl concentrations (Fig. 1a). The first bound peak (shaded in grey) represented the bulk of GSLL, which was collected from the final FPLC-gel filtration step on the Superdex 75 column. One major and three minor absorbance peaks were observed (Fig. 1b). The last minor peak constituted purified GSLL. From 80 g of lentil seeds, approximately 11.8 mg of GSLL was isolated, accounting for about 13 % of the total activity. Using this protocol, approximately 50-fold purification of GSLL was achieved. The efficiency of GSLL purification in each step could be observed by the SDS-PAGE results (Fig. 2a). In reducing SDS-PAGE using a 15 % polyacrylamide gel, the purified GSLL obtained from Superdex 75 yielded a 17-kDa band (Fig. 2a). When GSLL was subjected to non-reducing SDS-PAGE using a 15 % polyacrylamide tricine gel, a sharp 21-kDa band with two smaller lighter bands (17 and ~4 kDa) were observed (Fig. 2b). Hence, GSLL consisted of two subunits represented by these two smaller bands.

Table 1.

Steps for purification of GSLL

| Purification step | Yield (mg)/80 g seeds | Specific hemagglutinating activity (units/mg) | Total hemagglutinating activity (105 units) | Recovery of hemagglutinating activity (%) | Fold of purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 4647 | 138 | 6.42 | 100 | 1 |

| Affi-gel blue gel | 580.9 | 768 | 4.46 | 69.4 | 5.57 |

| Mono Q | 124.9 | 1024 | 1.28 | 19.9 | 7.42 |

| Superdex 75 | 11.8 | 6960 | 0.82 | 12.8 | 50.43 |

Fig. 1.

Elution profile for purification of GSLL through a Mono Q and b Superdex 75

Fig. 2.

a Results of reducing SDS-PAGE of fractions from various steps of purification using a 15 % polyacrylamide gel. Lane 1 crude seed extract; lane 2 Affi-gel blue gel, bound fraction; lane 3 Mono Q, first bound peak, purified lectin from Superdex 75, last peak; lane M protein ladder. b Results of non-reducing SDS-PAGE of GSLL using a 15 % polyacrylamide tricine gel. Lane 5 GSLL; lane M protein ladder

Both ion exchange chromatography steps were carried out in a pH 7.6 buffer. GSLL was adsorbed on Mono Q, but not on SP-Sepharose, indicating that GSLL was anionic at this pH, and had a pI value lower than pH 7.6. However, GSLL was eluted from Superdex 75 at about 18.5 mL. Based on the Superdex 75 calibration curve for size determination, GSLL should have a molecular size of approximately 2.6 kDa. The actual size of GSLL should be much larger (≥21 kDa) than the observed size, meaning that GSLL was not eluted from Superdex 75 in keeping with its molecular size.

Mass spectrometry after trypsin digestion (cutting of lysine and arginine residues on the C-terminal side unless the next amino acid was proline) of GSLL was performed, and the mass values obtained were searched using NCBI BLAST to find matching peptides. In the NCBI BLAST analysis, GSLL showed the highest similarity to LcL with 275 amino acids (Table 2). Nine fragments of GSLL were found to match, covering 29 % of the sequence of LcL.

Table 2.

Results for mass spectrometry of trypsin-digested GSLL

| No. | Sequence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MASLQTQMIS | FYLIFLSILL | TTIFFFKVNS | TETTSFSITK | FSPDQKNLIF |

| 51 | QGDGYTTKGK | LTLTKAVKST | VGRALYSTPI | HIWDRDTGNV | ANFVTSFTFV |

| 101 | IDAPSSYNVA | DGFTFFIAPV | DTKPQTGGGY | LGVFNSKEYD | KTSQTVAVEF |

| 151 | DTFYNAAWDP | SNKERHIGID | VNSIKSVNTK | SWNLQNGERA | NVVIAFNAAT |

| 201 | NVLTVTLTYP | NSLEEENVTS | YTLNEVVPLK | DVVPEWVRIG | FSATTGAEFA |

| 251 | AHEVHSWSFH | SELGGTSSSK | QAADA | ||

The results were matched and compared using NCBI BLAST, and GSLL showed highest similarity to LcL

Match to: LEC_LENCC (LcL) Score: 57

Nominal mass (Mr): 30261; Calculated pI value: 5.37

Number of mass values searched: 90; Number of mass values matched: 9; Sequence Coverage: 29 %

Matched sequence no.: 41–46, 66–68, 69–73, 74–85, 138–141, 142–163, 164–175, 181–189, 231–238; Matched peptides shown in boldface

The sequence of the first 15 amino acids from the N-terminus of GSLL was found to be TETTSFSITKFSPDQ. This sequence was identical to amino acids 31 through 45 of LcL, as shown in Table 2. A protein BLAST search on this segment revealed that it matched with LcL (100 % identical), as well as some other species (e.g., Lens nigricans [100 % identical], Cajanus cajan [100 % identical], Vigna aconitifolia [100 % identical], Cicer arietinum [100 % identical], Lathyrus ochrus [93 % identical], Pisum sativum [93 % identical], Lathyrus sativus [93 % identical]) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Protein BLAST results for the N-terminal amino acid sequence of GSLL

| Description | Sequence | Score | Identity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSLL | 1 | TETTSFSITKFSPDQ | 15 | ||

| Lentil lectin Chain A | 1 | TETTSFSITKFSPDQ | 15 | 50.3 | 100 |

| Lentil lectin precursor | 31 | TETTSFSITKFSPDQ | 45 | 50.3 | 100 |

| lectin [Lens nigricans] | 31 | TETTSFSITKFSPDQ | 45 | 50.3 | 100 |

| lectin [Cajanus cajan] | 31 | TETTSFSITKFSPDQ | 45 | 50.3 | 100 |

| lectin [Vigna aconitifolia] | 24 | TETTSFSITKFSPDQ | 38 | 50.3 | 100 |

| lectin [Cicer arietinum] | 24 | TETTSFSITKFSPDQ | 38 | 50.3 | 100 |

| Isolectin [Lathyrus ochrus-Chain A] | 1 | TETTSFSITKFGPDQ | 15 | 46.9 | 93 |

| Lectin [Garden Pea (Pisum Sativum)] | 1 | TETTSFLITKFSPDQ | 15 | 44.3 | 93 |

| lectin [Lathyrus sativus] | 22 | TETTSFLITKFSPDQ | 36 | 44.3 | 93 |

Residues that differ from GSLL are in boldface and underlined

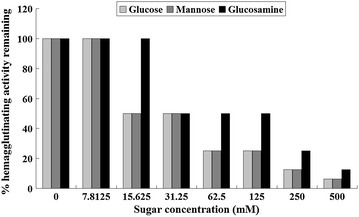

In the carbohydrate specificity test, addition of specific binding sugars for GSLL would lead to competition for binding sites of GSLL, causing competitive inhibition of GSLL binding onto the surface sugars of the red blood cells, thereby reducing the hemagglutinating activity of GSLL. The results revealed that GSLL was a glucose- and mannose-specific lectin. Among the various tested carbohydrates, galactose, rhamnose, arabinose, N-acetylgalactosamine, raffinose, mannitol, and xylitol did not affect the hemagglutinating activity of GSLL. On the other hand, glucose and mannose strongly inhibited the hemagglutinating activity of GSLL, followed by glucosamine, while maltose, α-methyl-d-glucoside, and α-methyl-pyranoside slightly inhibited the hemagglutinating activity. The minimal concentrations of glucose and mannose with an inhibitory effect were about 15.6 mM, and that of glucosamine was about 31.2 mM (Fig. 3). Moreover, increases in the sugar concentrations enhanced the inhibitory effect, and the residual hemagglutinating activity was further reduced.

Fig. 3.

Effects of glucose, mannose, and glucosamine on the hemagglutinating activity of GSLL. Increases in the concentrations of the specific sugars of GSLL strengthened the effects of competitive inhibition on the hemagglutinating activity. The tests were performed three times

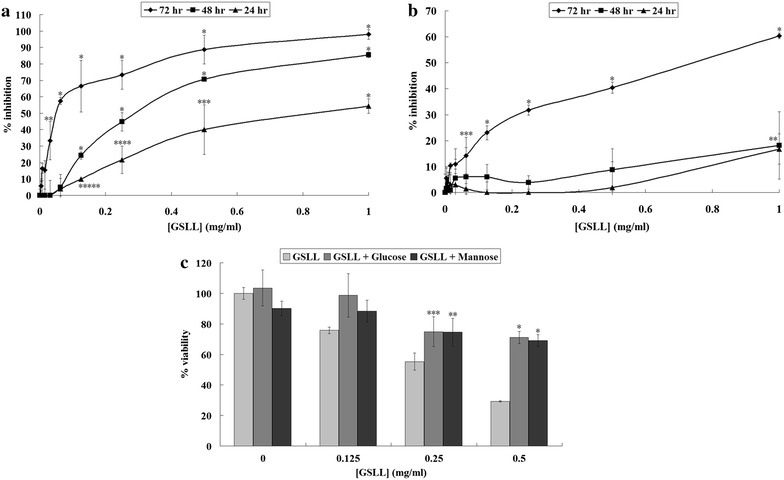

In the MTT assay, GSLL inhibited cell proliferation. GSLL strongly inhibited nasopharyngeal carcinoma CNE1 cells, and slightly inhibited CNE2 cells. Treatment with 0–1 mg/mL GSLL resulted in antiproliferative effects on CNE1 cells. After treatment with GSLL for 24, 48, and 72 h, significant inhibition was observed for the GSLL concentrations of 0.125 mg/mL (P = 0.0113), 0.125 mg/mL (P < 0.001), and 0.031 mg/mL (P = 0.004), respectively, and their respective IC50 values were 0.95, 0.28, and 0.06 mg/mL (Fig. 4a). CNE2 cells were much less responsive to GSLL treatment. Non-significant antiproliferative activity was detected after 24 h (i.e. for 1 mg/mL GSLL treatment, the data point with 16 % inhibition was P > 0.05). Slight inhibition of 18 % was detected after treatment with 1 mg/mL GSLL for 48 h (P = 0.004). The activity was more obvious when the duration of GSLL treatment was lengthened to 72 h, and the inhibitory effect was significant starting from 0.063 mg/mL GSLL (P = 0.044), with an IC50 value of 0.75 mg/mL (Fig. 4b). In the presence of 62.5 mM glucose or mannose, the specific sugars of GSLL, the antiproliferative effects of GSLL on CNE1 cells were reduced (Fig. 4c). After treatment with 0.25 mg/mL GSLL for 48 h, the presence of glucose and mannose significantly reduced the inhibitory effects of the lectin on CNE1 cells from 55.25 to 74.85 % (P = 0.043) and 74.52 % (P = 0.036), respectively. After treatment with 0.5 mg/mL GSLL, the inhibitory effects were reduced from 29.25 to 71.05 % (P < 0.001) and 69.11 % (P < 0.001), respectively, in the presence of glucose and mannose. The IC50 values after GSLL treatment were also elevated from 0.28 to 1.11 mg/mL and 1.79 mg/mL with the addition of glucose and mannose, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Results of the MTT assay for GSLL-treated a CNE1 and b CNE2 cells for 24, 48, or 72 h, and c GSLL-treated CNE1 cells under co-treatment with 62.5 mM glucose or mannose for 48 h. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). The marked data points represent those with significant differences of P < 0.05: a *P < 0.001, **P = 0.004, ***P = 0.0082, ****P = 0.0095, *****P = 0.0113; b *P < 0.001, **P = 0.004, ***P = 0.044; c *P < 0.001, **P = 0.036, ***P = 0.043

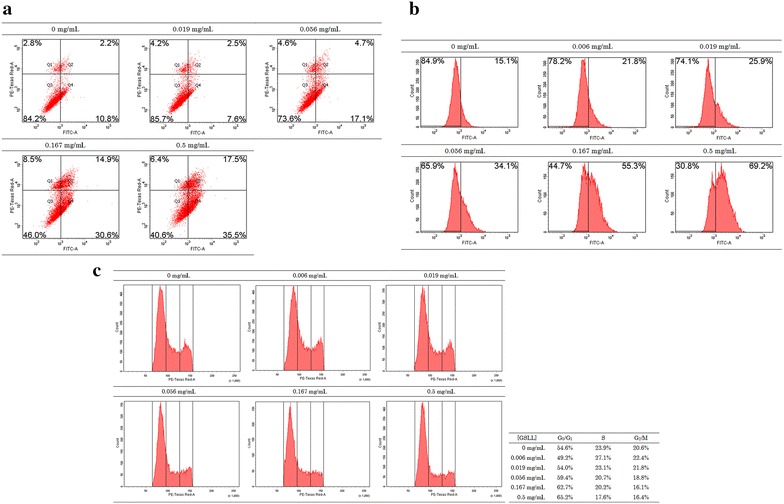

In flow cytometry experiments, GSLL induced apoptosis in CNE1 cells. Upon annexin V-FITC and PI staining, an increase in GSLL concentration from 0 to 0.5 mg/mL led to a rightward shift of the majority of the cells, the population of cells located at the lower left quadrant (healthy cells) was decreased, and the population located at the lower right quadrant (early apoptotic cells with phosphatidylserine externalization) was increased. The cell population at the upper right quadrant (late apoptotic or necrotic cells) was also increased, indicating that GSLL was cytotoxic toward the cells (Fig. 5a). Upon JC-1 staining, an increase in GSLL concentration from 0 to 0.5 mg/mL led to an increase in the intensity of green fluorescence (cells with mitochondrial depolarization) in the majority of the cells (Fig. 5b). In cell cycle analysis, an increase in GSLL concentration from 0 to 0.5 mg/mL reduced the populations of cells at S phase and G2/M phase (Fig. 5c), indicating that GSLL blocked cell cycle progression by arresting the cells at G1 phase. From the western blotting analysis, GSLL treatment triggered apoptosis of CNE1 cells with activation of caspase 3, 8, and 9 (Fig. 6). Specifically, an obvious decrease in the level of pro-caspase 9 and a slight decrease in pro-caspase 3 were detected, while the levels of active cleaved caspase 3 and 8 were slightly elevated, and that of active caspase 9 was more significantly increased.

Fig. 5.

Results of flow cytometry for 48-h GSLL-treated CNE1 cells examined for a phosphatidylserine externalization (with annexin V-FITC and PI staining), b mitochondrial depolarization (with JC-1 staining), and c cell cycle analysis (with PI staining)

Fig. 6.

Results of western blotting analysis for 48-h GSLL-treated CNE1 cells

Discussion

The sequence of GSLL partially matched that of LcL. LcL has a 30-kDa precursor form with 275 amino acids; the 1st to 30th amino acids form the signal peptide chain, the 31st to 210th amino acids belong to the lectin β-chain, and the 218th to 269th amino acids belong to the lectin α-chain, with the remaining amino acids located in the propeptides. LcL is a heterotetramer composed of two α-chains and two β-chains [8, 9]. The two chains have isoelectric points of pH 8.2 and 8.8, respectively, and that of their native form is pH 8.6 [21].

There were dissimilarities of GSLL from LcL. In the purification protocol, GSLL was not adsorbed on the cation exchanger SP-Sepharose, but was adsorbed on the anion exchanger Mono Q in pH 7.6 Tris–HCl buffer. GSLL should have a pI value below 7.6, which was lower than that of LcL [21]. The matching sequences of GSLL mainly fell into the β-chain of LcL, covering 73 of 180 amino acids of the β-chain (40.6 %). A segment of GSLL also matched with the α-chain of LcL, covering 8 of 50 amino acids of the α-chain (16 %). GSLL appeared as a 21-kDa band in non-reducing SDS-PAGE, with subunits displaying molecular sizes of 17 and ~4 kDa. The size of the 17-kDa band corresponded with that of the β-chain of LcL. However, the ~4-kDa subunit of GSLL was smaller than the α-chain of LcL (5.7 kDa) [8]. While the N-terminal amino acid sequence of GSLL was found to be TETTSFSITKFSPDQ, which was identical to that of the LcL β-chain, GSLL probably had at least 83 amino acids matching with the 180 amino acids of the LcL β-chain (46.1 %).

From the results of the western blotting analysis, GSLL increased the activation of caspase 3, 8, and 9 in CNE1 cells, suggesting an initiation of the caspase cascade in apoptosis.

LcLs can bind to cell surface polysaccharides and glycoproteins [22, 23]. GSLL showed a strong inhibitory effect on CNE1 cells, but exhibited a slight suppressive action on CNE2 cells. CNE1 is a well-differentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line, while CNE2 is a poorly-differentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line [24]. These two nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines exhibit differences in morphology, and expression levels of surface proteins. Despite its similar carbohydrate specificity with LcL, GSLL showed differential binding capability to these cell lines.

GSLL exhibited cytotoxic effects on the two cell lines. GSLL treatment caused phosphatidylserine externalization, mitochondrial depolarization, and cell cycle arrest, finally leading to cell death. GSLL might induce apoptosis selectively in cells with high expression levels of glucose- and mannose-containing glycoproteins, depending on its carbohydrate binding capability.

There are no previous reports on the induction of apoptosis in tumor cells by lectins from L. culinaris. Furthermore, most of the lectins (e.g., L. nigricans lectin, C. cajan lectin, V. aconitifolia lectin) with N-terminal amino acid sequences similar to GSLL have not been reported to elicit apoptosis in tumor cell lines or exhibit antiproliferative activities. To our knowledge, GSLL is the first lectin from the Lens genus to exhibit proapoptotic activities on tumor cells.

Among the lectins with N-terminal amino acid sequence homology to GSLL, only P. sativum lectin (pea lectin) triggered apoptosis in tumor cells [25]. Similar to GSLL, pea lectin was specific in glucose and mannose binding. It was also composed of two subunits with different molecular sizes, although the sizes of both subunits were slightly larger than those of GSLL (19.5 and 5 kDa). Pea lectin caused 84 % inhibition of Ehrlich ascites carcinoma (EAC) cells at a concentration of 120 µg/mL [25]. Addition of a caspase-3 inhibitor and caspase-8 inhibitor could reduce the inhibitory activity of pea lectin on EAC cells, indicating an association of this activity with the extrinsic apoptotic pathway involving caspase 3, 8, and 9 [25]. GSLL blocked cell cycle progression by arresting the cells at G1 phase (Fig. 5c), while pea lectin inhibited EAC cell proliferation by arresting the cells at G2/M phase [25].

Conclusion

GSLL possessed some different properties from LcL (e.g., lower pI), and increased caspase 3, 8, and 9 activity in CNE1 cells.

Authors’ contributions

LXX and TBN designed the study. YSC performed the experiment. TBN, YSC and HMY wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the funding of National Nature Science Foundation of China (NSFC) from Science and Technology Innovation Committee of Shenzhen City (006995) (Code: NFSC(81273275)).

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- DMSO

dimethyl sulphoxide

- ECL

electrochemiluminescence

- FPLC

fast protein liquid chromatography

- GSLL

green speckled lentil lectin

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- LcH

Lens culnaris hemagglutinin

- LcL

Lens culnaris lectin

- MTT

4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PI

propidium iodide

- PVDF

polyvinylidene difluoride

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacylamide gel electrophoresis

Contributor Information

Yau Sang Chan, Email: chanyausang@szu.edu.cn.

Huimin Yu, Email: yuhuimin@szu.edu.cn.

Lixin Xia, Email: xialixin@szu.edu.cn.

Tzi Bun Ng, Email: b021770@mailserv.cuhk.edu.hk.

References

- 1.Karaköy T, Erdem H, Baloch FS, Toklu F, Eker S, Kilian B, Özkan H. Diversity of macro- and micronutrients in the seeds of lentil landraces. Sci World J. 2012;2012:710412. doi: 10.1100/2012/710412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thavarajah D, Thavarajah P, Sarker A, Vandenberg A. Lentils (Lens culinaris Medikus Subspecies culinaris): a whole food for increased iron and zinc intake. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:5413–5419. doi: 10.1021/jf900786e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIntosh M, Miller C. A diet containing food rich in soluble and insoluble fiber improves glycemic control and reduces hyperlipidemia among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr Rev. 2001;59:52–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb06976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazzano LA, He J, Ogden LG, Loria C, Vupputuri S, Myers L, Whelton PK. Dietary intake of folate and risk of stroke in US men and women: NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Stroke. 2002;33:1183–1189. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000014607.90464.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell DC, Lawrence FR, Hartman TJ, Curran JM. Consumption of dry beans, peas, and lentils could improve diet quality in the US population. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:909–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito Y, Tsurudome M, Yamada A, Hishiyama M. Interferon induction in mouse spleen cells by mitogenic and nonmitogenic lectins. J Immunol. 1984;132:2440–2444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Combe E, Pirman T, Stekar J, Houlier ML, Mirand PP. Differential effect of lentil feeding on proteosynthesis rates in the large intestine, liver and muscle of rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard IK, Sage HJ, Stein MD, Young NM, Leon MA, Dyckes DF. Studies on a phytohemagglutinin from the lentil. II. Multiple forms of Lens culinaris hemagglutinin. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:1590–1595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foriers A, Lebrun E, Van Rapenbusch R, de Neve R, Strosberg AD. The structure of the lentil (Lens culinaris) lectin. Amino acid sequence determination and prediction of the secondary structure. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:5550–5560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young NM, Leon MA, Takahashi T, Howard IK, Sage HJ. Studies on a phytohemagglutinin from the lentil. 3. Reaction of Lens culinaris hemagglutinin with polysaccharides, glycoproteins, and lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:1596–1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welty LA, Heinrich EL, Garcia K, Banner LR, Summers ML, Baresi L, Metzenberg S, Coyle-Thompson C, Oppenheimer SB. Analysis of unconventional approaches for the rapid detection of surface lectin binding ligands on human cell lines. Acta Histochem. 2006;107:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choong PF, Teh HX, Teoh HK, Ong HK, Choo KB, Sugii S, Cheong SK, Kamarul T. Heterogeneity of osteosarcoma cell lines led to variable responses in reprogramming. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11:1154–1160. doi: 10.7150/ijms.8281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun Y, Qin L, Liu D, Liu C, Sun Y, Duan Y. Fast detection of alpha-fetoprotein-L3 using Lens culinaris agglutinin immobilized gold nanoparticles. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2014;14:4078–4081. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.8652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi X, Yu S, Bao Y. Alpha-fetoprotein-L3 in hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;425:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cortés-Giraldo I, Girón-Calle J, Alaiz M, Vioque J, Megías C. Hemagglutinating activity of polyphenols extracts from six grain legumes. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:1951–1954. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang EF, Lin P, Wong JH, Tsao SW, Ng TB. A lectin with anti-HIV-1 reverse transcriptase, antitumor, and nitric oxide inducing activities from seeds of Phaseolus vulgaris cv. extralong autumn purple bean. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:2221–2229. doi: 10.1021/jf903964u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan YS, Wong JH, Fang EF, Pan W, Ng TB. Isolation of a glucosamine binding leguminous lectin with mitogenic activity towards splenocytes and anti-proliferative activity towards tumor cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma A, Wong JH, Lin P, Chan YS, Ng TB. Purification and characterization of a lectin from the Indian cultivar of French bean seeds. Protein Pept Lett. 2010;17:221–227. doi: 10.2174/092986610790226067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santiago MQ, Leitão CC, Pereira FN, Jr, Pinto VR, Jr, Osterne VJ, Lossio CF, Cajazeiras JB, Silva HC, Arruda FV, Pereira LP, Assreuy AM, Nascimento KS, Nagano CS, Cavada BS. Purification, characterization and partial sequence of a pro-inflammatory lectin from seeds of Canavalia oxyphylla Standl. & L. O. Williams. J Mol Recognit. 2014;27:117–123. doi: 10.1002/jmr.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glenn G. Preparation of protein samples for mass spectrometry and N-terminal sequencing. Methods Enzymol. 2014;536:27–44. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420070-8.00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhattacharyya L, Brewer CF. Isoelectric focusing studies of concanavalin A and the lentil lectin. J Chromatogr. 1990;502:131–142. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)89570-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raczkowska J, Ohar M, Stetsyshyn Y, Zemła J, Awsiuk K, Rysz J, Fornal K, Bernasik A, Ohar H, Fedorova S, Shtapenko O, Polovkovych S, Novikov V, Budkowski A. Temperature-responsive peptide-mimetic coating based on poly(N-methacryloyl-l-leucine): properties, protein adsorption and cell growth. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2014;118:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanada H, Ohno J, Seno K, Ota N, Taniguchi K. Dynamic changes in cell-surface expression of mannose in the oral epithelium during the development of graft-versus-host disease of the oral mucosa in rats. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, Chen Y, Li Y, Chen W, Pan J, Su Y, Zou C. Raman microspectroscopy as a diagnostic tool to study single living nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines. Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;91:182–186. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2012-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kabir SR, Nabi MM, Haque A, Zaman RU, Mahmud ZH, Reza MA. Pea lectin inhibits growth of Ehrlich ascites carcinoma cells by inducing apoptosis and G2/M cell cycle arrest in vivo in mice. Phytomedicine. 2013;20:1288–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]