Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the number and types of discrepancy errors present after discharge from home health care in older adults at risk for medication management problems following an episode of home healthcare. More than half of the 414 participants had at least one medication discrepancy error (53.2%, n=219) with the participant’s omission of a prescribed medication (n=118, 30.17%) occurring most frequently. The results of this study support the need for home health clinicians to perform frequent assessments of medication regimens to ensure that the older adults are aware of the regimen they are prescribed, and have systems in place to support them in managing their medications.

One of the most difficult challenges for home health care clinicians is to discharge an older adult who would benefit from additional visits, but is no longer eligible for Medicare Homecare. For the chronically ill, self-management of a medication regimen is an ongoing critical task, yet the current Medicare home health program is based on episodic care, leaving a group of vulnerable older adults at high risk for problems in self-managing their care. Medication self-management is one area where episodic care is especially problematic.

Older adults are challenged due to the prevalence of multiple chronic conditions resulting in complex medication regimens usually prescribed by multiple providers (Coleman, Smith, Raha, & Min, 2005; Kogut, Goldstein, Charbonneau, Jackson, & Patry, 2014; Vogelsmeier, 2013). It is estimated that 25% of hospitalizations are related to medication discrepancies (Duran-Garcia, Fernandez-Llamazares, & Calleja-Hernandez, 2012). Factors such as cognitive impairment, depression, and decreased physical functioning also contribute to problems in medication self-management in this population (K.D. Marek & Antle, 2008). Medication nonadherence is often not intentional. Poor communication and lack of understanding of changes in a prescribed medication regimen are leading causes of medication discrepancy errors (Cua & Kripalani, 2008; Karapinar-Carkit et al., 2010). Home care clinicians facilitate communication among providers and promote self-management of medications. However, at discharge from home health care, such support is no longer available to this vulnerable population.

Although home care clinicians address medication management in the provision of home healthcare, patients who need medication assistance but are otherwise designated to be in a stable condition are not eligible for nursing visits under the current Medicare home health benefit. Despite efforts to prepare the older adult to self-manage their medications, many are at high risk for future medication problems at discharge from home healthcare. This is especially true for individuals who do not have engaged family or other persons to assist them in management of their medications. Many older adults are at risk without systems in place to support the complex activities of managing medications and other aspects of chronic disease. The purpose of this study was to examine the number and types of discrepancy errors present after discharge from home health care in older adults at risk for medication management problems following an episode of home health care.

Background

A medication-discrepancy is a specific type of medication error that occurs when unexplained differences among documented medication regimens occur. This type of error poses a major barrier to safe medication practices. Medication-discrepancy errors often occur when there are differences between what a patient actually takes, based on self-reports, and what is listed in the medical record(s)(Bedell et al., 2000). These errors frequently include the wrong dosage, duplicate dosages, omission of prescribed or over-the-counter medications and intended or unintended medication variances in the prescribed regimen (Gleason et al., 2010; Vira, Colquhoun, & Etchells, 2006). Maintaining an accurate list of prescribed medications, including both the dosage and frequency of each medication is a challenge for both prescribers and users of medications. Inaccurate lists are a major cause of medication-discrepancy errors. Often, there are several prescribers contributing to the medication regimen increasing the likelihood that discrepancy errors will occur. Common reasons for discrepancy errors in older adults include forgetting to have a new prescription filled, not changing a dose or frequency as instructed by a prescribing provider, and finishing an old prescription before obtaining new medication.

Transitions of care are an especially vulnerable time for medication discrepancies to occur (Sinvani et al., 2013). As a result, medication reconciliation is now a standard practice on admission to most health care settings. However, medication discrepancies remain prevalent. For example, studies of medication discrepancies on admission to the hospital range from 22 to 70 percent (Feldman et al., 2012; Hellstrom, Bondesson, Hoglund, & Eriksson, 2012; Kilcup, Schultz, Carlson, & Wilson, 2013; Pourrat et al., 2013; Unroe et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2008; Ziaeian, Araujo, Van Ness, & Horwitz, 2012), admission to the nursing home post hospitalization were reported to be 86% (Boockvar, Carlson LaCorte, Giambanco, Fridman, & Siu, 2006) and at discharge to home from skilled nursing facility 90% of patients were found to have a drug-related problem in their medication regimen (Delate, Chester, Stubbings, & Barnes, 2008). Examination of medication lists provided by patients during an emergency department visit revealed that 80% contained a discrepancy error (Caglar, Henneman, Blank, Smithline, & Henneman, 2011). On admission to assisted living communities post hospitalization 86.2% of the patient medication lists contained medication discrepancies (Fitzgibbon, Lorenz, & Lach, 2013). Finally, a study of medication lists used by home healthcare providers following hospitalization found 59% contained medication discrepancies (Bruning & Selder, 2011).

Methods

Study Design

A descriptive cross-sectional design was employed in this secondary analysis of data from the Home Care Medication Management for the Frail Elderly study (R01-NR008911) (K. D. Marek et al., 2013). The primary study used a longitudinal repeated measures design, enrolling and randomly assigning participants discharged from three home healthcare agencies in a large Midwestern urban region of the United States. The purpose of the primary study was to determine whether a home care medication management interventional program which included nurse care coordination and the use of a medication-dispensing machine would affect older adults’ health outcomes, health costs and satisfaction with healthcare services over a one year period. Before the intervention was delivered, medication reconciliation was conducted on all study participants.

To identify participants for medication management problems the primary study used two questions from the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS), a federally mandated assessment that is completed on all individuals receiving Medicare-financed home health services (Shaunnessy, Crisler, Hittle, & Schlenker, 2002). Inclusion criteria for the study were: (a) age 60 or older, (b) Medicare primary payer, (c) impaired ability to manage medications as indicated by a score of 1 or higher on OASIS item M0780, (d) impaired cognitive functioning but able to follow directions with prompting, as indicated by a score of 1 or 2 on OASIS item MO560, and (e) working telephone line and electricity. Exclusion criteria were (a) terminal diagnosis or hospice care that would suggest attrition and (b) use of other device for medications (such as pager as a prompt).

Medication Reconciliation

During the enrollment period into the primary study, a nurse-driven medication reconciliation assessment was completed on all participants. The first step in the medication reconciliation process was the creation of a medication list from the older adult’s perspective. Research nurses visited older adults in their homes and asked for a list of medications they were currently taking. This process included examination of the older adult’s medication lists from past hospitalizations, discharge medication lists obtained from the home-care service agencies, provider driven medication lists in the older adult’s possession, medication bottles, self-report(s), and any other means the older adult identified and utilized to track any and all medications. A complete list that included drug name, route, dosage and dosing interval was created. The older adult’s medication list was sent to the prescribing provider(s) for verification and clarification. A comparison of what medications the older adult was actually taking (self-report), including doses, and frequencies to what was actually documented on the medical record (recorded medications) occurred. Frequently, multiple prescribers were contacted to coordinate a medication list, requiring multiple phone calls and faxes to the prescribers and the participants. Reconciliation was complete when one congruent medication list was obtained.

Medication Discrepancy Error

Medication discrepancy errors were identified by comparing the older adult’s self-reported medication list to the medication list(s) identified by the prescribing provider(s). Any inconsistency including discrepancies in dose, defined as a change in the number of tablets or pills, frequency defined as a change in the number of times per day, or strength, defined as a change in milligrams etc. between the participant’s and prescribing provider(s)’ lists were counted as medication discrepancy errors. Finally, any errors of omission including medications not listed by the participant, or errors of commission which were medications listed that were discontinued by the prescriber but still being taken by the participants were also counted. After discrepancies were identified, they were categorized.

Data Analysis and Results

Using SPSS® v.15.0, we examined descriptive statistics for the demographic variables of age, living arrangements, hearing and vision deficit, cognition, number of discrepancy errors, difficulty purchasing medications and number of providers. Medication discrepancy errors were categorized by the type of errors that occurred. A total of 414 participants were included in the secondary analysis and ranged in age from 60-100 years with a mean age of 79.18 (SD = 7.64) years. Slightly more than 70% of the participants were over the age of 75. The majority of the study sample consisted of women (66%). More than 80% (n=351) of participants were white, and almost half (49.27%) of the participants lived alone. The mean score for cognition as measured by the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE)(Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) was 25.61 (SD = 3.428) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants (n = 414)

| Characteristic | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 60 to 74 | 121 | 29.2 |

| 75 to 84 | 182 | 44.0 |

| 85+ | 111 | 26.8 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 140 | 33.82 |

| Female | 274 | 66.18 |

| Race/Ethnicity* | ||

| Caucasian | 351 | 84.78 |

| African American | 62 | 14.97 |

| Hispanic | 11 | .03 |

| Lives Alone | 204 | 49.27 |

| Hearing Impairment | 116 | 28.00 |

| Visual Impairment | 76 | 18.3 |

| Cognitive impairment (MMSE) | ||

| No impairment (30-27) | 193 | 70.69 |

| Mild impairment (26-21) | 70 | 25.64 |

| Moderate (20-16) | 10 | 3.60 |

| Financial difficulty with medications | 74 | 17.87 |

Participants self-identified with more than 1 category

Only 74 (17.87%) of the participants reported financial difficulty purchasing routine medications. The mean number of prescribers contributing to the medication lists was 1.93, with a range of 1 to 9. Almost half of the participants (48.7%) had more than one prescriber contributing to the regimen with 9% reporting four or more prescribers contributing to their medication lists. The average number of medications taken each day by participants was 11 (Range 2-27). The mean number of doses per day required to maintain the medication regimen was 16.50 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medication Related Characteristics

| n | % | M (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Difficulty Purchasing Medications | 74 | 17.87 | - | - |

|

| ||||

| Number of Prescribers | - | |||

| 1 | 208 | 1.93(1.28) | 1 - 9 | |

| 2 - 3 | 165 | |||

| ≥4 | 41 | |||

|

| ||||

| Number of Medications | - | - | 11.01 (4.466) | 2-27 |

|

| ||||

| Daily Doses | - | - | 16.50 (8.29) | 2-55 |

Medication Discrepancy

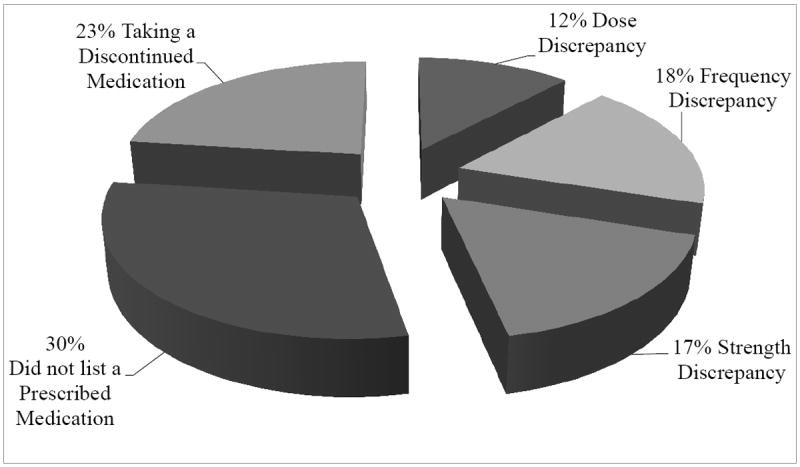

More than half of the participants had at least one medication discrepancy error (52.89%, n =219) during enrollment into the primary study. The mean number of discrepancy errors was 1.79 (SD 1.187, range 1-5). A total of 391 errors were identified and categorized by type. The most common type of discrepancy error was the participant’s omission of a medication that was prescribed (n=118, 30.17%). The second most common type of discrepancy error was the inclusion of a medication that had been previously discontinued (n=90, 23.01%). Other discrepancy errors included strength discrepancies (n=70, 17.90%), frequency discrepancies (n=66, 16.87%) and dose discrepancies (n=47, 12.02%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Medication Discrepancy Error by Type

(Total medication discrepancy errors=391)

Discussion

Findings from this study suggest that frail older adults with complex medication regimens experience a high rate of medication discrepancy errors after discharge from home health care. Although no longer eligible for the Medicare home healthcare benefits, the majority of older adults in this study were struggling with a basic element in managing their chronic conditions. The majority of medication use occurs in the community, but much of our understanding about the prevalence and impact of medication discrepancy errors are discovered during reconciliation processes in transitions of care. Post discharge is a safety area neglected in the current health care system (Tsilimingras & Bates, 2008).

What is unique about the findings from this study is that reconciliation occurred several weeks after discharge from home- health care and participants were not acutely ill. Reconciliation occurred in the participant’s home where the participant had complete access to any medication lists given to them in previous hospitalizations or other transitions in care, a time when new lists are often generated. They had full access to medication bottles, or other sources of medication information to assist in their self-reported medication list.

When the study nurse first arrived at the participant’s home to initiate the medication reconciliation process, participants would often gather large stockpiles of both old and new medications, as well as multiple medication lists from various providers and hospitalizations. Once gathered, participants in collaboration with the research nurses, would attempt to create current accurate lists of medications. On the second or even third visit, participants would reveal prescriptions that were never filled and medications long forgotten or overlooked during the initial visits. Often nurses and other healthcare professionals are quick to attribute medication errors to patient-driven factors including cost and non-adherence. It is estimated that 10% to 70% of older adults are not taking medications as prescribed due to system-driven issues including inaccurate medication information such as wrong dose, wrong drug, or wrong frequency (Meredith et al., 2002).

Previous studies have revealed that cost-related non-adherence is also common in elderly low-income, chronically ill patients (Briesacher, Gurwitz, & Soumerai, 2007; Kennedy & Morgan, 2009). In our analysis, approximately 18% of participants reported difficulty with purchasing routine medications. This is similar to other studies that estimate rates between 12-30% among disabled individuals and Medicare recipients (Briesacher et al., 2011). During the study period, Medicare Part D, the federal prescription drug coverage plan, was implemented and could have potentially lowered the incidence of cost related non-adherence. Of note however, was that during the primary study the intervention nurses were actively assisting the participants in planning for the drug coverage gap or “donut hole” that occurs under Part D at the time of the study. When necessary, study nurses explored discount drug programs, samples from physician offices, changing to generic medications, secondary insurance payer benefits and state and local drug purchasing assistance programs. It is unclear if intentional non-adherence related to cost was a mitigating factor in why participants failed to disclose all of their prescribed medications. This underscores the need for healthcare professionals to critically assess the medication cost burden of older, chronically ill adults, especially in polypharmacy situations.

Improving Community Based Medication Reconciliation

Findings from this study suggest that medication assessments and reconciliation activities are needed on an ongoing basis regardless of setting, to prevent adverse drug events, unnecessary emergency room visits and hospital admissions, and to decrease the number of medication related mortalities. This study revealed multiple medication discrepancy errors affecting the medication regimens of more than half of the participants. This highlights the desperate need for systems and structures in place that allow for ongoing medication reconciliation outside of the typical healthcare setting. Interprofessional programs that include pharmacist review in the reconciliation process are demonstrating favorable results in both hospital and community settings (Cumbler, Carter, & Kutner, 2008; Feldman et al., 2012; Reidt et al., 2014; Vogelsmeier, 2013).

In the community, evidence based interventions that include multiple assessments over much longer periods of time are needed. Medication reconciliation, procurement, knowledge, physical ability, cognitive capacity, intentional nonadherence, and ongoing monitoring of medication effectiveness are essential components of medication management (K.D. Marek & Antle, 2008). During the home health episode, medication regimens should be assessed regularly for additions, deletions, or changes in medication dosage. Often, older adults do not reveal all the medications they are taking or not taking until they are comfortable with their home care clinician. Also, mistakes such as not breaking a pill in half, for correct dosage can occur if they are administering their medications independently.

System such as mediplanners or blister packs provide support in the organization and administration of medications. Before discharging an older adult with medication management problems, a system must be in place for them to independently manage their medications. Many pharmacies will deliver blister packs, which are a useful system for many older adults. However, it is essential to monitor the older adults use of the blister pack to be sure they are able to administer their medication independently. If blister packs are not available, identification of a person to assist them, such as procuring and filling a device such as a mediplanner is important.

Limitations

With respect to limitations, the participants in this study were frail chronically ill older adults with impaired medication management abilities and/or impaired cognitive functioning in one Midwestern community. Although not representative of all older adults, this group is representative of a growing segment of the older adult population, who due to their frail status struggle to manage their chronic illness and often complex medication regimens.

The focus of this study was on medication-discrepancy errors present in the medication regimens of frail older adults living in the community including unintentional medication non-adherence. Intentional non-adherence with a prescribed medication regimen was not addressed in this analysis. We recognize that some medication discrepancies could be intentional, especially related to the ability to pay for medications. We did identify if the older adult had problems paying for their medications. In gathering the older adult’s medication lists, we asked the older adult to identify the list of medications they were taking; however, we did not examine the older adults’ adherence to the medications they identified in their list as a part of the reconciliation.

Summary

Appropriate prescribing of medications for older adults has received great attention in the past decade. However, for many frail older adults, accurately taking the appropriately prescribed medications is a challenge. Complex medication regimens with multiple medications and prescribing providers can be unmanageable for a chronically ill older adult, especially one with cognitive impairment. The results of this study support the need for additional assessments of medication regimens to ensure that the older adults are aware of the medication regimen they are prescribed, and have systems in place to support them in managing their medication regimens. The current Medicare home health benefit is episodic and does not address the needs of chronically ill older adults.

Understanding that medication reconciliation is an iterative, ongoing process and not a single intervention delivered during, or immediately after hospitalization may decrease the number of medication related adverse events. This will potentially improve health outcomes and provide a cost savings for the healthcare system. The reconciliation process in the acute care setting is well established. But ongoing, community-based medication reconciliation activities, beyond that done in home-health care admissions, are not an integral part of the care for chronically ill older adults. The results of this study suggest that assessment of an older adult’s medication regimen may require multiple assessments over much longer periods of time.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee Self-Management Science Center (P20NR010674-01) and the Home Care Medication Management for the Frail Elderly (R01-NR008911).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Contributor Information

Rachelle Lancaster, University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

Karen Dorman Marek, College of Nursing & Health Innovation, Arizona State University, Phoenix, Arizona.

Linda Denison Bub, Director of Education and Program Development Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem, Elders- NICHE, New York University College of Nursing.

Frank Stetzer, College of Nursing, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

References

- Bedell SE, Jabbour S, Goldberg R, Glaser H, Gobble S, Young-Xu Y, Ravid S, et al. Discrepancies in the use of medications: their extent and predictors in an outpatient practice. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(14):2129–2134. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boockvar KS, Carlson LaCorte H, Giambanco V, Fridman B, Siu A. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. 2006;4(3):236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briesacher BA, Gurwitz JH, Soumerai SB. Patients at-risk for cost-related medication nonadherence: a review of the literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(6):864–871. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0180-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briesacher BA, Zhao Y, Madden JM, Zhang F, Adams AS, Tjia J, Soumerai SB, et al. Medicare part d and changes in prescription drug use and cost burden: national estimates for the medicare population, 2000 to 2007. Medical Care. 2011;49(9):834–841. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182162afb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruning K, Selder F. From hospital to home healthcare: the need for medication reconciliation. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2011;29(2):81–90. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0b013e3182079893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caglar S, Henneman PL, Blank FS, Smithline HA, Henneman EA. Emergency department medication lists are not accurate. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2011;40(6):613–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min SJ. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165(16):1842–1847. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.16.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cua YM, Kripalani S. Medication use in the transition from hospital to home. Ann Academic Medicine Singapore. 2008;37(2):136–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumbler E, Carter J, Kutner J. Failure at the transition of care: challenges in the discharge of the vulnerable elderly patient. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2008;3(4):349–352. doi: 10.1002/jhm.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delate T, Chester EA, Stubbings TW, Barnes CA. Clinical outcomes of a home-based medication reconciliation program after discharge from a skilled nursing facility. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(4):444–452. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran-Garcia E, Fernandez-Llamazares CM, Calleja-Hernandez MA. Medication reconciliation: passing phase or real need? International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2012;34(6):797–802. doi: 10.1007/s11096-012-9707-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman LS, Costa LL, Feroli ER, Jr, Nelson T, Poe SS, Frick KD, Miller RG, et al. Nurse-pharmacist collaboration on medication reconciliation prevents potential harm. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2012;7(5):396–401. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbon M, Lorenz R, Lach H. Medication reconciliation: reducing risk for medication misadventure during transition from hospital to assisted living. Journal of Gerontologic Nursing. 2013;39(12):22–29. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20130930-02. quiz 30-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason KM, McDaniel MR, Feinglass J, Baker DW, Lindquist L, Liss D, Noskin GA. Results of the Medications At Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) Study: An Analysis of Medication Reconciliation Errors and Risk Factors at Hospital Admission. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1256-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom LM, Bondesson A, Hoglund P, Eriksson T. Errors in medication history at hospital admission: prevalence and predicting factors. BMC Clinical Pharmacology. 2012;12:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-12-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede SD, Zoer J, Siegert C, van Tulder M, Egberts AC, van den Bemt PM. The effect of the COACH program (Continuity Of Appropriate pharmacotherapy, patient Counselling and information transfer in Healthcare) on readmission rates in a multicultural population of internal medicine patients. BMC Health Service Research. 2010;10:39. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy J, Morgan S. Cost-related prescription nonadherence in the United States and Canada: a system-level comparison using the 2007 International Health Policy Survey in Seven Countries. Clinical Therapy. 2009;31(1):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilcup M, Schultz D, Carlson J, Wilson B. Postdischarge pharmacist medication reconciliation: impact on readmission rates and financial savings. Journal of the American Pharm Association (2003) 2013;53(1):78–84. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2013.11250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogut SJ, Goldstein E, Charbonneau C, Jackson A, Patry G. Improving medication management after a hospitalization with pharmacist home visits and electronic personal health records: an observational study. Drug Healthcare Patient Safety. 2014;6:1–6. doi: 10.2147/dhps.s56574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek KD, Stetzer F, Ryan PA, Bub LD, Adams SJ, Schlidt A, O’Brien A, et al. Nurse Care Coordination and Technology Effects on Health Status of Frail Older Adults via Enhanced Self-Management of Medication: Randomized Clinical Trial to Test Efficacy. Nursing Research. 2013;62(4):269–278. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318298aa55. 210.1097/NNR.1090b1013e318298aa318255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek KD, Antle L. Medication Management of the Community-Dwelling Older Adult. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Vol. 1. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2008. Publication No. 08-0043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith S, Feldman P, Frey D, Giammarco L, Hall K, Arnold K, Ray WA, et al. Improving medication use in newly admitted home healthcare patients: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50(9):1484–1491. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourrat X, Corneau H, Floch S, Kuzzay MP, Favard L, Rosset P, Grassin J, et al. Communication between community and hospital pharmacists: impact on medication reconciliation at admission. International Journal of Clinial Pharmacology. 2013;35(4):656–663. doi: 10.1007/s11096-013-9788-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidt SL, Larson TA, Hadsall RS, Uden DL, Blade MA, Branstad R. Integrating a pharmacist into a home healthcare agency care model: impact on hospitalizations and emergency visits. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2014;32(3):146–152. doi: 10.1097/nhh.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaunnessy PW, Crisler KS, Hittle DF, Schlenker RE. OASIS and outcome based quality improvement in home health care. Denver, Colorado: Centers for Health Services Research; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sinvani LD, Beizer J, Akerman M, Pekmezaris R, Nouryan C, Lutsky L, Wolf-Klein G, et al. Medication reconciliation in continuum of care transitions: a moving target. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013;14(9):668–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsilimingras D, Bates DW. Addressing postdischarge adverse events: a neglected area. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2008;34(2):85–97. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unroe KT, Pfeiffenberger T, Riegelhaupt S, Jastrzembski J, Lokhnygina Y, Colon-Emeric C. Inpatient medication reconciliation at admission and discharge: A retrospective cohort study of age and other risk factors for medication discrepancies. Am Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. 2010;8(2):115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vira T, Colquhoun M, Etchells E. Reconcilable differences: correcting medication errors at hospital admission and discharge. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2006;15(2):122–126. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelsmeier A. Identifying medication order discrepancies during medication reconciliation: perceptions of nursing home leaders and staff. Journal of Nursing Management. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jonm.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JD, Bajcar JM, Wong GG, Alibhai SM, Huh JH, Cesta A, Fernandes OA, et al. Medication reconciliation at hospital discharge: evaluating discrepancies. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2008;42(10):1373–1379. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziaeian B, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH, Horwitz LI. Medication reconciliation accuracy and patient understanding of intended medication changes on hospital discharge. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;27(11):1513–1520. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2168-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]