Abstract

Researchers have sought to understand the processes that may promote effective parent-adolescent communication because of the strong links to adolescent adjustment. Mindfulness, a relatively new construct in Western psychology that derives from ancient Eastern traditions, has been shown to facilitate communication and to be beneficial when applied in the parenting context. In this article, we tested if and how mindful parenting was linked to routine adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation within a longitudinal sample of rural and suburban, early adolescents and their mothers (n = 432; mean adolescent age = 12.14, 46% male, 72% Caucasian). We found that three factors -- negative parental reactions to disclosure, adolescent feelings of parental over-control, and the affective quality of the parent-adolescent relationship -- mediated the association between mindful parenting and adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation. Results suggest that mindful parenting may improve mother-adolescent communication by reducing parental negative reactions to information, adolescent perceptions of over-control, and by improving the affective quality of the parent-adolescent relationship. The discussion highlights intervention implications and future directions for research.

Keywords: mindfulness, mindful parenting, adolescent disclosure, parental monitoring, mother-adolescent relationships

Introduction

Low levels of parental knowledge of adolescent activities and whereabouts have been linked to higher levels of adolescent problem behavior (Racz & MacMahon, 2011). Parents often gain knowledge through adolescent routine disclosure of information about their whereabouts and activities (Kerr, Stattin, & Burk, 2010; Tilton-Weaver, Marshall, & Darling, 2014), but parental solicitation of information may also be linked to knowledge in some contexts (Lippold, Greenberg, Graham, & Feinberg, 2014; Laird, Marrero, & Sentse, 2010). Researchers have sought to understand the processes that may promote effective parent-adolescent communication because of the links to adolescent adjustment. Supportive parental reactions to adolescent disclosure (Tilton-Weaver et al., 2010), adolescent perceptions of appropriate parental control (Kakihara, Tilton-Weaver, Kerr, & Stattin, 2010), and a warm parent-adolescent relationship (Blodgett Salafia, Gondoli, & Grundy, 2009) have been associated with more parent-child communication. Yet little is known about how meta-cognitive and meta-emotional processes of parenting, such as mindful parenting (Duncan, Coatsworth, & Greenberg, 2009a), may impact these communication processes.

Mindful parenting is the extension of mindfulness, or the awareness that arises through paying attention on purpose in the present moment, nonjudgmentally (Kabat-Zinn, 2003), to the interpersonal domain of parent-adolescent interaction (Duncan, Coatsworth, & Greenberg, 2009b). Parents who approach their adolescent with qualities found in mindful parenting such as present-centered, non-judgmental acceptance, non-reactivity, and compassion (Duncan et al., 2009a) may be more likely to effectively communicate with their adolescent, resulting in higher levels of routine adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation (Racz & McMahon, 2011). Aspects of mindful parenting may reduce parental negative reactivity to adolescent disclosure and adolescent feelings of parental over-control, and may engender a warmer parent adolescent relationship (Duncan et al., 2009b). Research on mindful parenting interventions has shown improvements in mother anger management and positive behavior exhibited towards adolescents (Coatsworth, Duncan, Greenberg, & Nix, 2010), yet little is known about whether and how mindful parenting may promote specific aspects of parent-adolescent communication. This article builds on prior work on the process of parent-adolescent communication, investigating if and how mindful parenting is linked to adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation. We test if the linkages between mindful parenting and mother-adolescent communication are mediated by negative reactions to disclosure, adolescent perceptions of over-control, and the affective quality of the parent-adolescent relationship.

Mindful Parenting

Mindfulness practice may increase individuals’ awareness of their moment-to-moment experiences (e.g., thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations). Present-centered awareness may enable individuals to break cycles of automatic and habitual responses to experiences and instead exercise more conscious choice about how to respond to their daily experiences (Goldstein, 2002). A present-centered focus may also increase an individual’s awareness of the experiences of others. Mindfulness training in adults has been linked to increases in self-control and greater attunement to others (Bögels, Hoogstada, van Duna, de Schuttera, & Restifo, 2008).

Similar to dispositional mindfulness (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007), mindful parenting includes elements of present-centered awareness in everyday life. However, mindful parenting extends mindfulness to include both the inter- and intra-personal processes specific to parenting. Kabat-Zinn and Kabat-Zinn (1997) describe mindful parenting as paying attention to your child in an intentional, present-centered and nonjudgmental manner. Five main elements of mindful parenting have been proposed including: 1) listening with full attention (parents’ ability to pay close attention and listen carefully to their adolescents during moment-to-moment parenting interactions); 2) self-regulation in the parent-adolescent relationship (parents’ ability to bring awareness to their reactivity to their adolescents’ behavior and calmly select and implement parenting behaviors intentionally); 3) emotional awareness of self and adolescent (noticing their own emotions as they arise and change, as well as those of their adolescent, during parenting interactions); 4) nonjudgmental acceptance of self and adolescent (parents’ awareness of their attributions and expectations of their adolescents and the cultivation of openness and acceptance toward their own and their adolescents’ traits, attributes, and behaviors); and 5) compassion for self and adolescent (parents’ genuine sense of concern for their adolescents, themselves as parents, and the struggles they all face) (Duncan et al., 2009a).

Mindful parenting may enable parents to more accurately and correctly interpret their adolescents’ verbal and non-verbal cues. Mindful parenting may enable parents to break cycles of automatic reactivity to adolescent behaviors by increasing their ability to notice their reactions, pause, and then select an appropriate response. Indeed, training in mindful parenting has been linked to reduced emotional reactivity and better anger management in parents and improved parent-adolescent relationships, such as positive affect (Coatsworth et al., 2010; Duncan et al., 2009b). It is likely that mindful parenting also impacts parent-adolescent communication (Coatsworth et al., 2015), yet these links have not yet been tested.

Linkages between Mindful Parenting and Parent-Adolescent Communication

First, parents who are more mindful in their parenting may be less likely to have negative reactions to routine adolescent disclosures, which may promote more parent-adolescent communication. Negative parental reactions to adolescent disclosures, such as angry, uninterested, or rejecting responses, may inhibit parent-adolescent communication; such responses have been linked to reductions in adolescent disclosure over time (Tilton-Weaver et al., 2010). Mindful parents may be more likely to pause, listen carefully, and reflect deeply about what their adolescents are disclosing. Such self-regulatory and awareness cultivation processes may make parents less emotionally reactive to adolescent disclosures, and better able to consciously choose how to respond. For example, parents engaging in mindful parenting may be less likely to react with anger if an adolescent discloses information about a sensitive topic, such as a poor grade on a test, and may be more likely to listen to the adolescent’s explanation. Compassion for the adolescent and non-judgmental acceptance may also lead to fewer negative reactions and attributions when parenting mindfully. In turn, supportive parental responses may facilitate more parent-adolescent communication. Parents who are more compassionate and better able to regulate their emotional reactions may be more comfortable soliciting youth for information about their activities, and their adolescent may be more likely to disclose information.

Second, mindful parenting, with its focus on acceptance and non-judgment, may reduce adolescent feelings of parental over-control. Several studies suggest that adolescents may disclose less information when they perceive their parents to be intrusive or controlling (Tilton-Weaver et al., 2010) and when they believe that their parents are invading their privacy (Hawk, Hale, Raaijmakers, & Meeus, 2008). Adolescents who perceive their parents to be over-controlling may inhibit or withhold information from their parents as a mechanism to meet age-typical needs for autonomy and independence (Marshall et al., 2005). A mindfulness orientation to parenting may make parents more likely to be oriented towards the present rather than the past (Duncan et al., 2009b). Thus, mindful parents may also be more likely to recognize their adolescents’ growing need for autonomy and independence and be more responsive to their changing developmental needs (Deci & Ryan, 2010) and, therefore, more likely to solicit information in a manner that respects youth autonomy. Further, parents with higher levels of mindful parenting may be less judgmental and more accepting and compassionate in their interactions with their adolescents, which may also be linked to lower adolescent perceptions of parental over-control and subsequently higher levels of adolescent routine disclosures.

Third, mindful parenting may promote a warmer, closer parent-adolescent relationship, which may lead to increases in parent-child communication. A few studies suggest that both adolescent disclosure and parents’ family management strategies may be influenced by the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship (Blodgett Salafia et al., 2009; Lippold et al., 2014). Adolescents who experience close, warm, trusting parent-adolescent relationships are more likely to disclose information (Blodgett Salafia et al., 2009) and less likely to keep secrets (Engels, Finkenauer, & van Kooten, 2006). Given their need for relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2010), adolescents may manage the information they share with their parents in an effort to maintain a close parent-adolescent relationship (Marshall et al., 2005). Aspects of mindful parenting, such as non-judgmental acceptance, emotional awareness of self and adolescent, and compassion, may engender a closer parent-adolescent relationship, with positive implications for parent-adolescent communication.

Early Adolescence

Mindful parenting may be particularly important for parent-adolescent communication during the adolescent transition, when levels of solicitation and disclosure typically decline (Keijsers & Poulin, 2013). Adolescents spend increasingly less time with their parents and more unsupervised time with peers (Lam, McHale, & Crouter, 2012), making it more difficult for parents to consistently keep track of their adolescents’ experiences. Further, parents may need to adapt their parenting strategies to support adolescents’ growing need for autonomy (Wray-Lake, Crouter, & McHale, 2010). Increases in parent-adolescent conflict and parental feelings of ineffectiveness and strain may increase during early adolescence, as parents and adolescents transition to more egalitarian relationships (Collins & Laursen, 2006). Mindful parents’ ability to remain focused on the present moment may enable them to recognize and respond to their adolescents’ current developmental needs, rather than relying on past expectations and prior parenting strategies (Duncan et al., 2009a) and to capitalize on brief, focused opportunities to solicit information from their adolescents and to listen to youth disclosures. Thus, mindful parents’ ability to regulate their own emotions and have compassion for themselves and their adolescents may help them maintain close positive relationships with their adolescents during this time period.

This Study

Here, we investigate whether mindful parenting is associated with increased mother-adolescent communication across three waves of data within one school year in families of 6th and 7th graders. We hypothesize that mindful parenting may be linked to increases in parental solicitation and routine adolescent disclosure through three mediating mechanisms. First, more mindful parents may be less behaviorally reactive and therefore less likely to engage in harsh parenting in response to adolescent disclosure of information than less mindful parents. Second, mindful parenting, with its focus on acceptance and non-judgment, may be associated with lower levels of adolescent feelings of parental over-control. Third, because mindful parenting emphasizes skills for promoting a close interpersonal connection, including compassion and acceptance, it may promote a warmer parent-adolescent relationship on affective indicators. These three processes -- reducing negative behavioral reactions to disclosure and adolescent perceptions of over-control and increasing parent-adolescent warmth -- in turn, may be linked to increases in adolescent routine disclosure and parental solicitation of information.

Method

Participants

Four hundred and thirty-two mothers and their adolescents participated in this study. Seventy- two percent of adolescents were White European American, 16% were Black, 4% were Asian, 1% was Native American, and 7% were multiracial; across racial categories, 8% of adolescents were Latino. Sixty-six percent of families (N = 286) included two parents. Twenty-five percent of mothers had a high school diploma or less; median annual family income was $49,000. Fifty-four percent of adolescents were female; adolescents were 12.14 (SD = .67) years old, on average, at the beginning of this study. All adolescents were in middle school, grades 6 – 8, throughout this study.

Procedures

During four consecutive academic years, families of 6th and 7th grade students in four school districts in rural and suburban areas of central Pennsylvania were invited to participate in a randomized controlled trial of the Mindfulness-Enhanced Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14 (MSFP; Coatsworth et al., 2015). Families were randomized to one of three study conditions: 1) the standard Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14 (SFP; Molgaard, Kumpfer, & Fleming, 2001), 2) MSFP, or 3) a home study control condition.

Assessments were conducted at three waves: baseline, prior to the beginning of the intervention; approximately eight weeks later, after the conclusion of the intervention; and approximately one year later. Assessments included paper and pencil measures that were mailed to both mothers and youths and an in-home assessment that included an additional computer-assisted survey. Families received incentives of $75, $100, and $125 to complete baseline, post-intervention, and one-year follow-up assessments, respectively. The current study is a secondary data analysis of data from all three assessments (Waves 1–3) controlling for intervention condition.

Measures

We used a measure of adolescent reports of mindful parenting collected at baseline, prior to the beginning of the intervention. Measures of our mediators-- adolescent reports of negative reactions to disclosure, over-control, and the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship-- were collected at baseline and approximately eight weeks later at post-intervention (Wave 2). Our outcomes, maternal report of routine adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation, were collected at baseline and approximately one year later (Wave 3). We chose to alternate reporters in this study, and henceforth used adolescent reports of mindful parenting and mother reports of routine adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation. We expect that alternating reporters may provide a more stringent test of effects, given that it may reduce common method variance.

Mindful parenting

Adolescent perceptions of mothers’ mindful parenting were measured using an expanded version of the Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting Scale (IM-P; Duncan, 2007), based on Duncan et al.’s model of mindful parenting (2009a). The adolescent-report version of the expanded IM-P contains 19 items on a Likert-type scale which assess adolescent perceptions of how frequently a parent listens with full attention, exhibits emotional awareness in parenting, shows self-regulation, and displays non-judgmental acceptance and compassion. Example items are “When I need to talk to my mother about something, she really pays attention to me” and “I feel like my mom accepts me just as I am, even if we do not always agree.” Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1= Never true to 5= Always true) and averaged to create a total score, with higher scores indicating more mindful parenting. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .89.

Negative reactions to disclosure

Adolescent perceptions of parents’ negative reactions to disclosure were measured using four items (Tilton-Weaver et al., 2010). An example item is “Have your parents ever used what you told them against you?” Parent behaviors were rated on a five-point scale (1= Hardly ever to 5= Always) and averaged to create a total score. The Cronbach alpha was .76.

Adolescent feelings of over-control

Adolescent perceptions of parents’ over-control were measured using five items (Kerr & Stattin, 2000). An example item is “Do you think your parents control everything in your life?” Items were rated on a six-point scale (0 = No, never to 5 = Yes, always) and averaged to create a total score. Cronbach’s alpha was .82.

Affective quality

Adolescent perceptions of the affective quality of the mother-adolescent relationship were measured using 14 items that assessed both positive and negative interactions in the affective domain of the relationship over the past month (Conger, 1989; Spoth, Redmond, & Shin, 1998). Example items include “How often does your mother let you know she really cares about you?” and “How often does your mother criticize your ideas?” (reverse scored). Items were rated on a seven-point scale (0 = Never to 6 = Always). Items were scored such that higher scores indicated more positive and less negative affective relationships and were averaged to create a total score. Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

Adolescent disclosure

Maternal perceptions of adolescent routine disclosure of their whereabouts and activities were measured using four items (Stattin & Kerr, 2000). An example item is “How often does this child tell you what he/she is doing without your asking?” Items were rated on a five-point scale (1 = Hardly ever to 5 = Always) and averaged with higher scores indicating more adolescent routine disclosure. Cronbach alpha was .84.

Parental solicitation

Mothers were asked how often in the last month they asked adolescents about their activities using five items (Stattin & Kerr, 2000). An example item is “How often did you ask this child about things that happened at school?” Items were rated on a five-point scale (0= Almost never to 4= Almost always) and averaged with higher scores indicating more parental solicitation. Cronbach’s alpha was .78.

Control variables

Covariates in this study included adolescent age, adolescent gender, highest level of parent education, family income, and parent marital status. Given the current study is a secondary analysis of data from an intervention trial, we controlled for intervention condition using dummy codes to indicate participation in SFP or MSFP, where the control group was the reference group. Our mindful parenting variable for the current study was assessed at baseline, prior to the intervention, and dummy coding provided us with the added precaution of parsing out any effects of MSFP or SFP on our mediation models. We also controlled for the baseline assessments of all mediators and all outcomes.

Results

Plan of Analysis

Path models were estimated in MPlus 7.2 (Muthen & Muthen, 2012). All variables assessed at the same time point were correlated. All models include both direct and indirect effects. Each model controlled for demographic characteristics, and intervention condition, and baseline levels of the mediator and the outcomes. All missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood procedures (Graham, Cumsille, & Elek-Fisk, 2003). At the one-year follow-up assessment, approximately 27% of families were missing outcome data; however, attrition was not related to baseline differences on any of the variables included in this study, except parent education.

Model goodness of fit was assessed using chi-square tests, and indices of model fit including Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993), the Non-normed Fit Index or Tucker Lewis Index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973; Bentler & Bonett, 1980), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990). Cutoffs of acceptable fit were .08 for RMSEA and .90 for TLI and CFI. We used the PRODCLIN program to test the significance of the mediated effect (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011). This program tests significance, based on the product of the two regression coefficients (from mindful parenting to the mediator, and the mediator to the outcome; MacKinnon et al., 2002).

We also investigated if the model paths differed between adolescents in the intervention and control groups. Using multiple group invariance tests, we compared the fit of a model in which the three substantive model paths were constrained to be equal across study condition groups to a model in which those paths were freely estimated. We compared changes in chi-square as well as in the CFI. A change in the CFI greater than .01 was used as an indicator of group differences (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002).

Descriptive Statistics

Means and correlations for study variables can be found in Table 1. Adolescent reports of mindful parenting were significantly and positively correlated with mother reports of adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation, suggesting that parents who are more mindful in their parenting were more likely to effectively communicate with their adolescents. Mindful parenting was also significantly correlated with adolescent reports of our three mediating variables: negative reactions to disclosure, adolescent perceptions of parental over-control, and the affective quality of the parent-adolescent relationship.

Table 1.

Means and correlations between study variables

| Mean | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mindful parenting | 2.75 | 0.67 | ||||||

| 2. Negative reactions to disclosure | 1.24 | 0.78 | −0.31*** | |||||

| 3. Youth perceptions of over control | 1.39 | 0.86 | −0.36*** | 0.50** | ||||

| 4. Affective-quality | 4.69 | 0.96 | 0.60*** | −0.46*** | −0.49*** | |||

| 5. Youth disclosure | 2.66 | 0.71 | 0.24** | −0.31*** | −0.34** | 0.26*** | ||

| 6. Parental solicitation | 2.78 | 0.60 | 0.27** | −0.16** | −0.16** | 0.23*** | 0.40*** |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001,

Means and correlations are presented from Wave 1 (baseline) for mindful parenting, Wave 2 (post-test) for negative reactions to disclosure, over control, and affective-quality, and Wave 3 (follow-up) for youth disclosure and parental solicitation.

Mediation Models

We investigated if negative reactions to disclosure, adolescent perceptions of over-control, and the affective quality of the parent-adolescent relationship mediated the relations between mindful parenting and adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation.

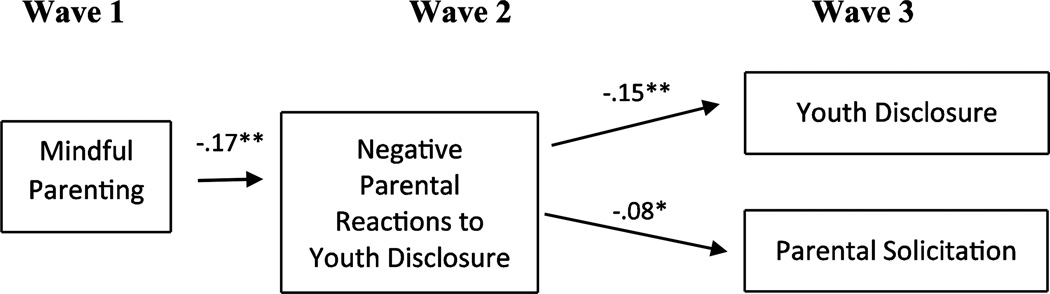

Negative reactions to disclosure

The fit of the first path model, in which negative reactions to disclosure was the mediator, was acceptable (X2 = 43.22, df = 22, p < .05; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .97; TLI = .93). As seen in Figure 1, adolescent report of mindful parenting at baseline was associated with fewer negative reactions to routine adolescent disclosure at post-intervention (B = −.17, SE = .06, p < .01), even when controlling for initial levels of negative reactions to routine adolescent disclosure. Fewer negative reactions, in turn, were associated with maternal reports of more routine adolescent disclosure (B = −.15, SE = .04 p < .01) and parental solicitation (B = −.08, SE = .03, p < .05) at follow-up, even when controlling for initial levels of these outcomes. Based on the PRODCLIN program, the mediated effects were significant for both disclosure (B =.03, CI [.005, .052], p < .05) and solicitation (B =.01, CI [.001, .029] p < .05). Residual direct effects represent the residual effect of the independent variable on the outcome after taking the mediator into account. Although the initial correlation between mindful parenting and routine adolescent disclosure was significant (r = .24, p < .01, from Table 1), the residual direct effect after taking the mediator into account was nonsignificant (B =.07, SE = .05, p = ns). Likewise, although the initial correlation between mindful parenting and parental solicitation was significant (r = .27, p < .01, from Table 1), the residual direct effect after taking the mediator into account was also nonsignificant (B =.07, SE = .04, p = ns).

Figure 1. Negative parental reactions to youth disclosure mediate the linkages between mindful parenting and youth disclosure and parental solicitation.

Note. Mindful parenting and over-control are reported by youth. Youth disclosure and solicitation are reported by mothers. Models include direct effects and control for Wave 1 levels of the mediator and outcome variables, intervention condition, and demographics (not shown).

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

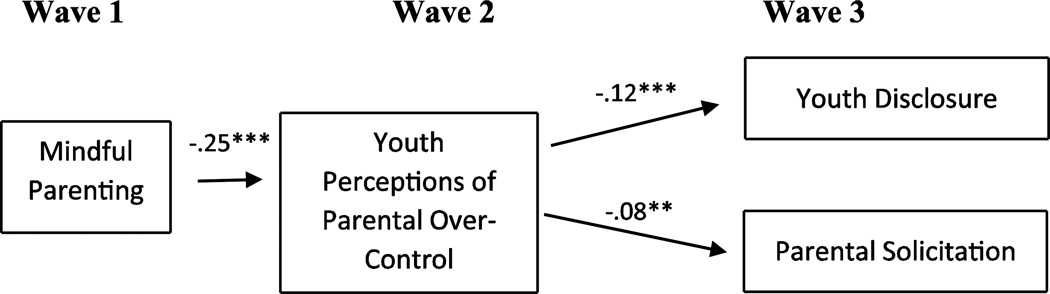

Adolescent perceptions of parental over-control

The fit of the second path model, in which adolescent perceptions of over-control was the mediator, was also acceptable (X2 = 53.14, df = 22, p < .05; RMSEA = .06; CFI = .95; TLI = .94). As seen in Figure 2, adolescent reports of mindful parenting at baseline was associated with a decrease in adolescent perceptions of parental over-control at post-intervention (B = −.25, SE = .06, p < .001). Lower perceptions of over-control, in turn, was associated with positive changes in routine adolescent disclosure (B = − .12, SE = .03, p < .001) and parental solicitation (B = −.08, SE = .03, p < .01) at follow-up. The mediated effects were significant for both disclosure (B = .03, CI [.011- .056], p < .05) and solicitation (B =.02, CI [.004 – .041] p < .05). All residual direct effects were non-significant (for disclosure B =.07, SE = .05, p = ns; for solicitation, B = .06, SE = .04, p = ns).

Figure 2. Youth perceptions of parental over-control mediate the linkages between mindful parenting and youth disclosure and parental solicitation.

Note. Mindful parenting and over-control are reported by youth. Youth disclosure and parental solicitation are reported by mothers. Models include direct effects and control for Wave 1 levels of the mediator and outcome variables, intervention condition, and demographics (not shown).

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

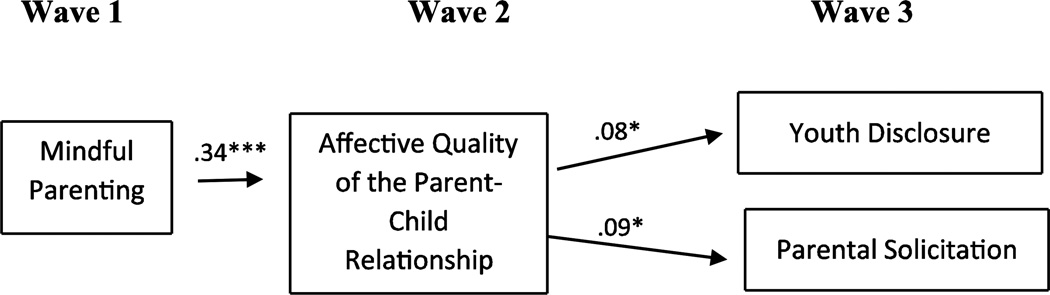

Affective quality

The fit of the final path model, in which adolescent perceptions of the quality of the affective mother-adolescent relationship was the mediator, was also good (X2 = 39.71, df = 22, p < .05; RMSEA = .04; CFI = .98; TLI= .98). As seen in Figure 3, mindful parenting at baseline was associated with an increase in the positive quality of the mother-adolescent affective relationship (B = .34, SE = .09, p < .001) at post-intervention, even controlling for initial levels of the affective quality of the relationship. More positive affect quality, in turn, was associated with positive changes in routine adolescent disclosure (B = .08, SE = .04, p < .05) and parental solicitation (B= .09, SE = .04, p < .05) at follow-up, one year later. The mediated effects were significant for both disclosure (B =.03, CI [.004- .061], p < .05) and solicitation (B =.03, CI [.004 – .062], p < .05). All residual direct effects were nonsignificant (for disclosure B = .06, SE = .06, p = ns; for solicitation, B= .03, SE = .05, p = ns).

Figure 3. The affective-quality of the parent-child relationship mediates the linkages between mindful parenting and youth disclosure and parental solicitation.

Note. Mindful parenting and affective quality are reported by youth. Youth disclosure and parental solicitation are reported by mothers. Models include direct effects and control for Wave 1 levels of the mediator and outcome variables, intervention condition, and demographics (not shown).

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Homogeneity of Results

As a check of our strategy of controlling for intervention participation in this secondary analysis of data collected in an intervention trial, we also investigated if our models differed between participants in different intervention conditions. We included both intervention and control-group families in this study. Even though SFP and MSFP were designed to change mean levels of the constructs featured in this study, they were not designed to change the relations among those constructs, which is the focus of this study. Nonetheless, we investigated if the model paths differed between mothers and adolescents in the intervention and control groups with multiple group invariance tests. We compared the fit of a model where the three substantive model paths (the relation between mindful parenting and the mediator, the relation between the mediator and routine adolescent disclosure, and the relation between the mediator and parental solicitation) were constrained to be equal across groups to a model where they were freely estimated. Three different sets of comparisons were run for each model: MSFP vs. control, SFP vs. control, and MSFP vs. SFP. We compared changes in chi-square as well as in the CFI. A change in the CFI greater than .01 was used as an indicator of group differences (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). No overall differences were found between MSFP and control groups or between the SFP and control groups for any of our mediation models: the chi square change was minimal and non-significant and the CFI change was less than .01. Similarly, no differences were noted between the MSFP and SFP groups in our mediation models for negative reactions to adolescent disclosure or adolescent perceptions of parental over-control. However, some differences emerged between the MSFP and SFP groups for the model in which the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship was the mediator. The chi-square difference was significant (Δχ2 = 11.07, df = 3, p < .05) but the change in CFI was not greater than .01. When each path in this model was examined separately, the chi-square difference test was significant only for the path between mindful parenting and the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship (Δχ2 = 8.51, df = 1, p < .01; B =.16, SE = .10, p =ns, for SFP vs. B = .63 SE=.13, p < .01, for MSFP), but there were no changes in CFI that were greater than .01. Given that only 1 of 27 possible paths (3 paths for 3 models for 3 study conditions) appeared different, we concluded that relations among constructs were generally comparable across study conditions and could be presented for the entire sample.

Discussion

Because high levels of parental knowledge about youth activities have been linked to positive youth outcomes, researchers have sought to understand the processes that may promote effective parent-adolescent communication (Racz & MacMahon, 2011). Mindfulness, a relatively new construct in Western psychology that derives from ancient Eastern traditions, has been shown to be beneficial when applied in the parenting context (Coatsworth et al., 2010; Duncan et al., 2009b). Aspects of mindful parenting such as present-centered attention, emotional awareness, self-compassion and compassion for one’s child, may be linked to increased youth disclosure and parental solicitation regarding youth activities (Duncan et al., 2009a). Yet, little is known about if and how mindful parenting may impact these parent-child communication processes. The goal of this study was to understand how mindful parenting may influence parent adolescent communication, such as routine adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation in families during early adolescence. We tested whether negative reactions to routine adolescent disclosure, adolescent perceptions of parental over-control, and the affective quality of the parent-adolescent relationship mediated the association between mindful parenting and mother-adolescent communication.

Our results suggest that mindful parenting may play an important role in promoting parent-adolescent communication. As predicted, adolescents who reported higher levels of their mothers’ mindful parenting were more likely to be perceived by their mothers as disclosing information about their activities. Further, mothers engaging in more mindful parenting were also more likely to solicit information from their adolescents. Parent-adolescent communication can be initiated by either mothers or adolescents, and our results indicate that mindful parenting may improve both forms (Lippold et al., 2013). These findings support other studies that have found mindful parenting to have important implications for parent-adolescent relationships and adolescent well-being (Coatsworth et al., 2010; Coatsworth et al., 2015), but also extend this work into the domain of parent-adolescent communication. Results indicate that parenting with present-centered, non-judgmental awareness, non-reactivity, and compassion is linked to more parent-adolescent communication, marked by increased disclosure and solicitation.

Our study also provides insight into how mindful parenting influences parent-adolescent communication. The associations between mindful parenting and adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation were mediated by adolescent reports of parents’ negative reactions to the adolescents’ disclosures and adolescent perceptions of the quality of the mother-adolescent relationship. Perhaps practicing mindful parenting increases parents’ ability to regulate their emotional responses, thus enabling them to stay calm and compassionate when adolescents share sensitive information. A central focus of mindful parenting is practicing present-centered attention through listening with full attention. Maintaining present-centered awareness, having compassion for themselves and the adolescent, and more fully listening, may enable mothers to develop closer parent-adolescent relationships, thereby meeting their adolescents’ need for connection and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2010). These findings support other research that has found parental reactions to information (Tilton-Weaver et al., 2010) and the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship may have important implications for parent-adolescent communication (Smetana et al., 2006).

We found that adolescents’ perceptions of parental over-control mediated the relationship between mindful parenting and routine adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation. Because mindful parents are more oriented to the present, they may be cognizant of and responsive to their adolescents’ changing needs for autonomy and privacy (Deci & Ryan, 2010). Mindful parents may be more comfortable granting adolescents more independence, which may reduce adolescents’ feelings of parental over-control. Such autonomy-granting may facilitate more open discussion between parents and their adolescent about a variety of topics via routine adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation. These finding support other work showing that parental respect for adolescent privacy (Hawk et al., 2008) and reduced adolescent perceptions of parental over-control (Kakihara et al., 2010) may promote communication.

Study Limitations and Strengths

This study has several limitations that provide important directions for future research. First, this study was conducted with a sample of primarily White European American adolescents residing in rural and suburban Pennsylvania. Future studies are needed to understand whether our findings are applicable to other cultural groups and adolescents residing in urban settings. Second, this study did not investigate the linkages between mindful parenting, parent-adolescent communication, and adolescent adjustment, such as externalizing or internalizing problems. More research is needed to understand how the specific processes explored in this study are linked to adolescent adjustment. Third, it is likely that our three mediating mechanisms are related to one another. For example, there is some evidence that reactions to disclosure may impact adolescent perceptions of parental over-control and connectedness to their parents (Tilton-Weaver et al., 2010). Future studies with a larger sample and more time points may shed light on which of these mediating processes has the strongest influence on parent-child communication and may allow closer examination of how these mediating processes interact with mindful parenting and one another over time. Fourth, although this study examined the mother-adolescent dyad, adolescents rated two of our mediators, negative reactions to disclosure and perceptions of parental over-control, in relation to both mothers and fathers. Most likely, however, the imprecision that resulted from rating both parents together rather than mothers independently made the relations to other aspects of mothers’ behaviors lower rather than higher. Fifth, our study relied on self-report data, which may contain some degree of bias. Sixth, study effect sizes were relatively small. Clearly, other factors not included in this study contribute to parent-adolescent communication. Seventh, some of our measures had floor or ceiling effects. Eighth, our subgroup analyses might have revealed so few significant differences across study conditions because of the smaller sample size in each of those study conditions. And, ninth, future studies are needed to understand which elements of mindful parenting may relate to fewer negative reactions to routine adolescent disclosure, less parental over-control, and stronger affective relationships (Parent et al., 2010). A more nuanced examination of mindful parenting may allow for further refinement of interventions aimed to improve parent-adolescent communication.

Despite these limitations, this study has several strengths. Many prior studies on mindfulness and parent-adolescent relationships have been cross-sectional (Guertzen et al., 2014). By using longitudinal data across three waves, we were able to establish the temporal precedence necessary to test mediation (Collins, 2006) and to show how sample-level changes in the mediators were associated with sample-level changes in the outcomes. We used multi-informant data from both mothers and adolescents in our models. Relying on measures from one reporter only may inflate model estimates due to common method variance. By alternating reporters in our models, we reduced the potential bias from common method variance. Lastly, this study focused on the mediational processes that may link mindfulness to parent-adolescent communication, highlighting potentially key intervention targets.

Conclusions

This study adds to a growing body of research on mindful parenting and its positive effects on the parent-adolescent relationship (e.g., Coatsworth et al., 2015). Our study findings suggest that mindful parenting has important implications for parent-adolescent communication; routine adolescent disclosure and parental solicitation. Prior studies have identified barriers to effective parent-child communication, such as negative parental reactions to disclosure (Tilton-Weaver et al., 2010), youth perceptions of parental over-control (Kakihara et al., 2010), and cold, unsupportive parent-child relationships (Blodgett Salafia et al., 2009). Mindful parenting may exert its influence on parent-adolescent communication by reducing these barriers to communication. The linkages between mindful parenting and parent-adolescent communication were mediated by negative reactions to disclosure and adolescent perceptions of over-control and by improving the quality of the parent-adolescent affective relationship.

Interventions to improve mindful parenting may be one avenue to promote parent-adolescent communication during early adolescence. Learning to be more mindful may increase parental self-awareness so they can note their own internal reactivity, choose to employ self-regulatory capacities, and therefore have fewer harsh reactions to their adolescents’ disclosures. Moreover, learning to be more mindful may help parents learn to effectively meet their adolescents’ changing needs for autonomy, so that the adolescents are less likely to perceive parents as intrusive and controlling. Finally, learning to be more mindful may help parents be warmer and more supportive in the affective domain of their relationships with their adolescents. Training in mindful parenting and other mindfulness practices may enable parents to more effectively adjust to the normative developmental changes that accompany the transition to adolescence. In the end, such practices may facilitate better communication between parents and adolescents, which will allow parents the opportunity to provide – and adolescents to accept -- more guidance as adolescents navigate the new challenges and many changes they may face.

Acknowledgements

Work on this article was supported by the National Institutes of Health through a research grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1 R01 DA026217) and a career award to L. G. Duncan from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (1 K01 AT005270). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Melissa Lippold, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor in The School of Social Work at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her program of work explores the role of parent-youth relationships in the prevention of problem behavior and the promotion of child health. She holds a Ph.D. in Human Development and Family Studies from the Pennsylvania State University and a dual Master’s degree in Social Work and Public Policy from the University of Chicago.

Larissa G. Duncan, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Department of Family and Community Medicine and a core faculty member of the UCSF Osher Center for Integrative Medicine. Her program of research focuses on studying mindful parenting and testing the impact of mindfulness interventions delivered to families during two key developmental transitions: pregnancy and early adolescence. She holds a Ph.D. in Human Development and Family Studies from The Pennsylvania State University.

J. Douglas Coatsworth is Professor of Human Development and Family Studies and Director of the Colorado State University Prevention Research Center. His research focuses on design and evaluation of family-focused interventions to promote competence and prevent problem behaviors and on how mindfulness can be applied to parenting. He holds a Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology from the University of Minnesota.

Robert Nix is a Research Associate in the Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center at The Pennsylvania State University. He develops and evaluates preventive interventions to promote positive social and emotional functioning among high risk children. He earned his doctorate in clinical child psychology from Vanderbilt University.

Mark T. Greenberg is the Bennett Chair of Prevention Research at The Pennsylvania State University Prevention Research Center and in Human Development and Family Studies. He received his Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology from the University of Virginia. His major research interests include prevention, substance use, and mindfulness.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

ML and LD conceived of the study and drafted the manuscript; ML conducted statistical analysis; JDC, LD, and MG designed and conducted the parent intervention study which provided the data for the study; RN provided statistical consultation; LD, JDC, MG, and RN participated in the interpretation of the data and reviewed all manuscript drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett Salafia EH, Gondoli DM, Grundy AM. The longitudinal interplay of maternal warmth and adolescents’ self-disclosure in predicting maternal knowledge. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19(4):654–668. [Google Scholar]

- Bögels S, Hoogstada B, van Duna L, de Schuttera S, Restifo K. Mindfulness training for adolescents with externalizing disorders and their parents. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;36:193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry. 2007;18:211–237. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9(2):233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Greenberg MT, Nix RL. Changing parent’s mindfulness, child management skills and relationship quality with their youth: Results from a randomized pilot intervention trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19(2):203–217. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9304-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Nix RL, Greenberg MT, Gayles JG, Bamberger KT, Berrena E, Demi MA. Integrating mindfulness with parent training: Effects of the Mindfulness-Enhanced Strengthening Families Program. Developmental Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1037/a0038212. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JAS, Semple RJ. Mindful parenting: A call for research. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19(2):145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equations models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM. Analysis of longitudinal data: The integration of theoretical model, temporal design, and statistical model. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:505–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Laursen B. Parent-adolescent relationships. In: Noller P, Feeney J, editors. Close relationships: Functions, forms, and process. New York: Psychology Press; 2006. pp. 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD. Iowa Youth and Families Project, Wave A. Report prepared for Iowa State University, Ames, IA: Institute for Social and Behavioral Research; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter A, Head M. Parental monitoring and knowledge of children. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of parenting. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erblaum; 2002. pp. 461–483. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination. In: Weiner IB, Craighead WE, editors. Corsini encyclopedia of psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2010. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LG. Assessment of mindful parenting among parents of early adolescents: Development and validation of the Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting scale. Unpublished dissertation. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LG, Coatsworth JD, Greenberg MT. A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent-child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009a;12(3):255–270. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LG, Coatsworth JD, Greenberg MT. Pilot study to gauge acceptability of a mindfulness-based, family-focused preventive intervention. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009b;30(5):605–618. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels RC, Finkenauer C, van Kooten DC. Lying behavior, family functioning and adjustment in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(6):949–958. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher AC, Steinberg L, Williams-Wheeler M. Parental influences on adolescent problem behavior: Revisiting Stattin and Kerr. Child Development. 2004;75:781–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein J. One dharma: The emerging Western Buddhism. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Golish T, Caughlin J. "I'd rather not talk about it": adolescents' and young adults' use of topic avoidance in stepfamilies. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2002;30(1):78–106. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Cumsille PE, Elek-Fisk E. Methods for handling missing data. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Handbook of psychology: Research methods in psychology. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. pp. 87–114. [Google Scholar]

- Geurtzen N, Scholte RH, Engels RC, Tak YR, van Zundert RM. Association Between Mindful Parenting and Adolescents’ Internalizing Problems: Non-judgmental Acceptance of Parenting as Core Element. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hawk ST, Hale WW, Raaijmakers QA, Meeus W. Adolescents’ perceptions of privacy invasion in reaction to parental solicitation or control. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28:583–608. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10(2):144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn M, Kabat-Zinn J. Everyday blessings: The inner work of mindful parenting. New York: Hyperion; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kakihara F, Tilton-Weaver L. Adolescents’ interpretations of parental control: Differentiated by domain and types of control. Child Development. 2009;80(6) doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakihara F, Tilton-Weaver L, Kerr M, Stattin H. The relationship of parental control to youth adjustment: Do youths’ feelings about their parents play a role? Journal of youth and adolescence. 2010;39(12):1442–1456. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keijsers L, Frijns T, Branje SJ, Meeus W. Developmental links of adolescent disclosure, parental solicitation, and control with delinquency: moderation by parental support. Developmental psychology. 2009;45(5):1314. doi: 10.1037/a0016693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keijsers L, Poulin F. Developmental changes in parent-child communication throughout adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49(12):2301–2308. doi: 10.1037/a0032217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H, Burk WJ. A reinterpretation of parental monitoring in longitudinal perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Marrero MD, Sentse M. Revisiting parental monitoring: Evidence that parental solicitation can be effective when needed most. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2010;39:1431–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CB, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Parent-child shared time from middle childhood to late adolescence: Developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development. 2012;83(6):2089–2103. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold MA, Coffman DL, Greenberg MT. Investigating the potential causal relationship between parental knowledge and youth risky behavior: A propensity score analysis. Prevention Science. 2013;15:869–878. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0443-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold MA, Greenberg MT, Collins LM. Parental knowledge and youth risky behavior: a person oriented approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42(11):1732–1744. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9893-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold MA, Greenberg MT, Feinberg ME. A dyadic approach to understanding the relationship of maternal knowledge of youths’ activities to youths’ problem behavior among rural adolescents. The Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1178–1191. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9595-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold MA, Greenberg MT, Graham J, Feinberg ME. Unpacking the effect of parental monitoring on early adolescent problem behavior: Mediation by parental knowledge and moderation by parent-youth warmth. The Journal of Family Issues. 2014;35:1800–1823. doi: 10.1177/0192513X13484120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SK, Tilton-Weaver LC, Bosdet L. Information management: Considering adolescents’ regulation of parental knowledge. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28(5):633–647. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masche JG. Explanation of normative declines in parents' knowledge about their adolescent children. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33(2):271–284. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molgaard VK, Kumpfer KL, Fleming E. The Strengthening Families Program: For parents and youth 10–14; A video-based curriculum. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Extension; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Parent J, Garai E, Forehand R, Roland E, Potts J, Haker K, Compas BE. Parent mindfulness and child outcome: The roles of parent depressive symptoms and parenting. Mindfulness. 2010;1(4):254–264. doi: 10.1007/s12671-010-0034-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racz SJ, McMahon RJ. The relationship between parental knowledge and monitoring and child and adolescent conduct problems: A 10-year update. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(4):377–398. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0099-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana J, Metzger A, Gettman DC, Campione-Barr N. Disclosure and secrecy in adolescent-parent relationships. Child Development. 2006;77:201–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13(1982):290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Luyckx L, Goossens L. Parenting and adolescent problem behavior: An integrated model with adolescent self-disclosure and perceived parental knowledge as intervening variables. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:305–318. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C. Direct and indirect latent-variable parenting outcomes of two universal family-focused preventive interventions: Extending a public health-oriented research base. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:385–399. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton-Weaver L. Adolescents’ information management: Comparing ideas about why adolescents disclose to or keep secrets from their parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43(5):803–813. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0008-4. 10.1007/s10964-013-0008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton-Weaver L, Kerr M, Pakalniskeine V, Tokic A, Salihovic S, Stattin H. Open up or close down: How do parental reactions affect youth information management? Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:333–346. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton-Weaver LC, Marshall SK, Darling N. What's in a name? Distinguishing between routine disclosure and self-disclosure. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014;24(4):551–563. [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43:692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Pschometrika. 1973;38(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wray-Lake L, Crouter AC, McHale SM. Developmental patterns in decision-making autonomy across middle childhood and adolescence: European American parents’ perspectives. Child Development. 2010;81(2):636–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]