Abstract

Cerebrovascular accident during hypertensive disorder of pregnancy is a rare entity, but carries high risk of mortality and morbidity due to its unpredictable onset and late diagnosis. Here, we report an unusual case of 20-year-old primigravida with 34 weeks gestation having no risk factor, which developed sudden atypical eclampsia and intracranial hemorrhage within few hours. She was successfully managed by multidisciplinary approach including emergency cesarean section and conservative neurological treatment for intraventricular hemorrhage.

Keywords: Atypical eclampsia, intraventricular hemorrhage, prolonged coma

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia/eclampsia is one of the most common risk factors for stroke in pregnancy, particularly during the postpartum period.[1] The incidence of stroke during pregnancy including cerebral venous thrombosis ranges from 10 to 34/100,000 deliveries.[2] In some patients, this can be complicated by atypical presentation of eclampsia, which is characterized by the occurrence of eclampsia before 20 weeks, after 48 h postpartum or in the absence of typical signs of hypertension and/or proteinuria.[3] Clinical literature regarding anesthetic and critical care management for eclampsia with stroke is very sparse. Only early diagnosis and management can improve the outcome in these patients. This unique case illustrates that timely diagnosis and multidisciplinary approach for management in eclamptic patient complicated by intracranial hemorrhage can decrease the mortality and morbidity associated with it, especially in developing countries.

CASE REPORT

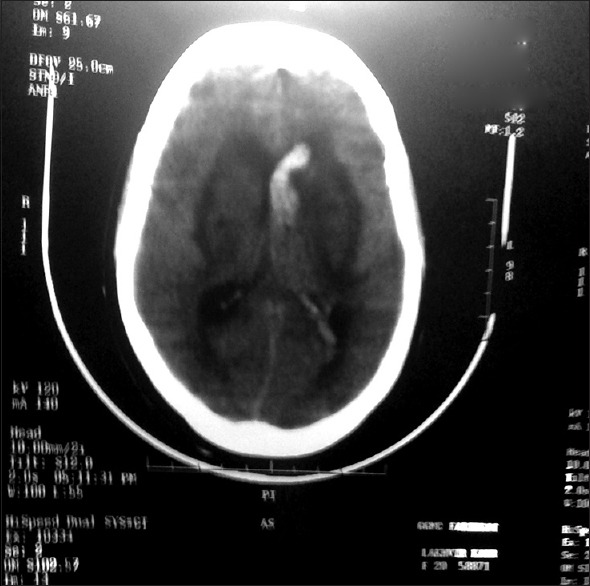

A 20-year-old primigravida of 34 weeks gestation with previous normal antenatal care, brought to the emergency with complaint of sudden onset of headache and epigastric pain since morning. On clinical examination, she was 34 weeks pregnant and not in the labor. Her vitals record of heart rate - 102/min, blood pressure (BP) - 170/100 and SpO2-96% were made. On provisional diagnosis of imminent eclampsia, supportive treatment started to control BP. She received injection labetalol 20 mg intravenous (i.v.) stat and magnesium sulfate 5 g i.m. in each buttock along with 4 g by i.v. infusion over 20 min. The patient was admitted to the obstetric high care unit for BP control with observation for any complication. Blood tests were ordered for urea, electrolytes, blood sugar, uric acid, full blood count, liver function and coagulation profile, which were found normal. Urine test was negative for proteinuria. Within 4 h of admission, patient had sudden generalized tonic-clonic seizures for which supportive treatment including oxygen with assisted ventilation and drugs, that is, midazolam, phenytoin, magnesium sulfate were given. Emergency lower segment caesarean section planned in view of persistent postictal drowsiness and high BP. Standard general anesthesia with rapid sequence induction was carried out for surgery. During intraoperative period, high BP after intubation was controlled with injection labetalol 20 mg i.v. stat again and a healthy male baby delivered with Apgar score of 7/10 at 1 and 5 min respectively. Postoperatively patient shifted to Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for elective ventilation due to persistent poor Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 5/15. Injection magnesium sulfate continued as per protocol with monitoring for magnesium toxicity along with antihypertensive drugs in ICU. After 24 h of surgery, computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was obtained in view of persisting low GCS, that is, 4/15. Scan showed intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) in all the ventricles with diffuse brain edema [Figure 1]. On the advice of neurosurgeon, conservative treatment with injection manitol, lasix, steroid, and levipril started. On 4th postoperative day, improvement in GCS was noted and weaning from the ventilator started. After the return of full conscious level, patient extubated on 7th day and repeated CT scan of head had shown resolving IVH with no brain edema. Patient discharged on 10th day in satisfactory condition with advice of regular follow-up.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography head showing intraventricular hemoorhage

DISCUSSION

Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy is a multisystem disorder. Usually, occurrence of eclampsia is warned by preeclampsia but sometimes patient may present with sudden onset without prior sign of preeclampsia (i.e., hypertension and proteinuria). In our case, patient was asymptomatic till 34 weeks of the antenatal period and suddenly develops neurological symptoms with high BP. Although the presence of hypertension, sudden headache, seizures and negative proteinuria supported our diagnosis of atypical eclampsia but persistent, prolonged coma directed us for considering other differential diagnosis of this condition. The most common cause of convulsions developing in association with hypertension and/or proteinuria during pregnancy or immediately postpartum is eclampsia. Rarely, other etiologies like ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, hypertensive encephalopathy, seizure disorder and metabolic disorder may mimic eclampsia.[4] Differential diagnoses are particularly important in the presence of focal neurologic deficits, prolonged coma, or atypical eclampsia. Cerebrovascular accident due to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy account for 28–50% of maternal deaths.[5] In our case of atypical eclampsia occurrence of sudden headache, seizure, and prolonged coma could be attributed to antepartum IVH. Intracranial hemorrhage could possibly be due to rupture of blood vessels, caused by the rapid increase in the hydrostatic forces that overwhelm autoregulatory mechanisms. One study concluded that brain edema in patients with preeclampsia-eclampsia syndrome is primarily associated with laboratory-based evidence of endothelial damage.[6]

Anesthetic management in unconscious eclamptic patients may present several dilemmas including rapid sequence induction while blocking the stress responses to laryngoscopy, drug interaction between magnesium sulfate with muscle relaxant, regarding use of internal jugular cannulation with brain edema and the risk of laryngeal edema presenting as difficult airway.[7,8] Until now, only two cases of successful management in eclamptic patient with intracerebral hemorrhage by craniotomy with cesarean section had been reported.[8,9] The importance of early clinical and radiological assessment of the central nervous system in eclampsia patient with a sudden decrease in conscious level has also been emphasized.[10] We report the first case of eclamptic patient with IVH, which was successfully managed by timely diagnosis and conservative treatment. Prolonged coma and prompt response to decongestant therapy in our patient can only be explained by brain edema with intraventricluar hemorrhage secondary to eclampsia.

CONCLUSION

As an anesthesiologist and critical care expert, we should always keep the possibility of hemorrhagic stroke in eclamptic patient especially in atypical presentation with persistent poor conscious level and focal neurological sign. Early diagnosis and multidisciplinary approach including anesthesiologist, obstetrician and neurosurgeon can improve the outcome in these patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lanska DJ, Kryscio RJ. Risk factors for peripartum and postpartum stroke and intracranial venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2000;31:1274–82. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.6.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang CH, Wu CS, Lee TH, Hung ST, Yang CY, Lee CH, et al. Preeclampsia-eclampsia and the risk of stroke among peripartum in Taiwan. Stroke. 2009;40:1162–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.540880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sibai BM, Stella CL. Diagnosis and management of atypical preeclampsia-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:481.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sibai BM. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:402–10. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000152351.13671.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin JN, Jr, Thigpen BD, Moore RC, Rose CH, Cushman J, May W. Stroke and severe preeclampsia and eclampsia: A paradigm shift focusing on systolic blood pressure. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:246–54. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000151116.84113.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boxer LM, Malinow AM. Preeclampsia and eclampsia. Curr Opin Anesth. 1997;10:188–98. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parthasarathy S, Hemanth Kumar VR, Sripriya R, Ravishankar M. Anesthetic management of a patient presenting with eclampsia. Anesth Essays Res. 2013;7:307–12. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.123214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roopa S, Hegde HV, Torgal SV, Melkundi S, Sunita TH, Mudaraddi RR, et al. Anesthetic management of combined emergency cesarean section and craniotomy for intracerebral hemorrhage in a patient with severe preeclampsia. Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 2010;21:292–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghaly RF, Candido KD, Sauer R, Knezevic NN. Complete recovery after antepartum massive intracerebral hemorrhage in an atypical case of sudden eclampsia. Surg Neurol Int. 2012;3:65. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.97167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mokoka V. Early postpartum eclampsia complicated by subarachnoid haemorrhage, cerebral oedema and acute hydrocephalus. S Afr J Anaesth Analg. 2003;9:19–22. [Google Scholar]