Abstract

Why has progress toward gender equality in the workplace and at home stalled in recent decades? A growing body of scholarship suggests that persistently gendered workplace norms and policies limit men's and women's ability to create gender egalitarian relationships at home. In this article, we build on and extend prior research by examining the extent to which institutional constraints, including workplace policies, affect young, unmarried men's and women's preferences for their future work-family arrangements. We also examine how these effects vary across levels of education. Drawing on original survey-experimental data, we ask respondents how they would like to structure their future relationships while experimentally manipulating the degree of institutional constraint under which they state their preferences. Two clear patterns emerge. First, as constraints are removed and men and women can opt for an egalitarian relationship, the majority of them choose this option, regardless of gender or education level. Second, women's relationship structure preferences are more malleable to the removal of institutional constraints via supportive work-family policy interventions than are men's. These findings shed light on important questions about the role of institutions in shaping work-family preferences, underscoring the notion that seemingly gender-traditional work-family decisions are largely contingent on the constraints of current workplaces.

Keywords: Gender inequality, Work-family policy, Preference formation

In recent decades, women have entered the labor force en masse, yet this trend has not been matched with a corresponding increase in men's share of unpaid household work, men's entry into traditionally female-dominated occupations, or substantial reforms to government and workplace policies (England 2010; Gerson 2010a; Hochschild and Machung [1989] 2003). Furthermore, women still comprise only a small minority of elite leadership positions in government, business, and academic science. For instance, women make up just four percent of Fortune 500 CEOs and eighteen percent of the 535 members in the U.S. Congress (Center for American Women and Politics 2013; Leahey 2012). And, although ideological support for women's employment has substantially increased since the 1970s, this trend leveled off in the mid-1990s (Bolzendahl and Myers 2004; Brewster and Padavic 2000; Cotter, Hermsen and Vanneman 2011; Thornton and Young-DeMarco 2001).

How can we explain this “stalled” gender revolution? One key dynamic that researchers point to is the disjuncture between contemporary institutional structures and individuals’ ideals. That is, even when individuals hold gender-egalitarian ideals, their choices, both about how much to work and in what occupation, are often constrained by workplace norms and policies that are generally unsupportive of individuals with family responsibilities (Cha 2010; 2013; Gerson 2010a; Stone 2007; Williams 2001; 2010). For instance, Kathleen Gerson (2010a) finds that many young, unmarried men and women ideally prefer to have egalitarian relationships where both partners contribute equally to earning and caregiving. However, they often doubt that this ideal preference is attainable given the reality of workplaces that demand long hours for a successful career and cultural norms that demand long hours for successful parenting. As a result, men and women end up employing fallback plans that are more gender-differentiated (with men preferring a more traditional arrangement, and women preferring an arrangement in which they can remain financially autonomous). Similarly, Stone (2007) finds that women who opt to forego their careers in order to care for their family typically do so as a last resort—only after they have encountered inflexible, even hostile, workplace environments.

The overall implication of these findings is that work-family preferences are formed largely in response to the constraints and options created by workplace institutions, and because these institutions are traditionally gendered, men's and women's patterns of behavior follow accordingly. However, observed work-family preferences and decisions may also reflect gender differences in preexisting, stable, and potentially internalized beliefs that individuals hold about men, women, caregiving, and earning. Indeed, scholars have argued that such gendered aspects of individuals’ identities operate alongside gendered institutions to maintain patterns of inequality (Ferree, Lorber and Hess 1999; Risman 1998). Thus, a critical challenge for researchers has been to determine the extent to which gendered preferences for employment and caregiving are produced by gendered institutional conditions (such as gendered workplace cultures and policies), independent of otherwise durable beliefs about gender at the individual-level. Prior studies have been limited in their ability to address this question because they rely on in-depth interviews or survey data, and thus cannot demonstrate the extent to which a causal relationship exists between institutional conditions and preference formation.

The goal of our study is to evaluate the direct relationship between institutional constraints and preference formation by drawing on original survey-experimental data from a representative U.S. sample of young, unmarried, childless individuals. Our study is designed to assess the extent to which men's and women's stated preferences for balancing future work and family responsibilities differ under high, medium, and low levels of institutional constraint. First, we use experimental methods to replicate and elaborate on Gerson's (2010a) findings by investigating how the distribution of men's and women's stated preferences for balancing work and family responsibilities differ depending on whether or not respondents are provided an egalitarian earner-caregiver relationship as a response option (thereby simulating high versus medium levels of institutional constraint). Second, we test the causal relationship between work-family policies and work-family preference formation by investigating how the distribution of men's and women's preferences differ depending on whether or not policies designed to support an egalitarian earner-caregiver arrangement (see Gornick and Meyers 2009a) are universally available (thereby simulating medium versus low levels of institutional constraint). Finally, we take advantage of our nationally representative sample to investigate how these patterns may vary for individuals whose educational pursuits have set them on a working class versus a white collar, or professional, employment trajectory.

Our results offer evidence that institutional constraints substantially influence young men's and women's work-family preferences. In particular, men's and women's relationship preferences converge toward egalitarianism when the option is made available to them. Furthermore, women's, but not men's, preferences are dramatically affected by the presence of supportive policies: women are significantly more likely to prefer an egalitarian relationship and significantly less likely to prefer a neotraditional relationship when supportive policies are available. Despite some variability by educational background in the overall distribution of men's and women's preferences, which we discuss in detail below, these effects of institutional constraints on preferences are fairly similar across education groups.

In contrast to studies that have documented the impact of workplace structures and policies on gender biases among managers and employers (Castilla and Benard 2010; Kalev 2009; Kalev, Dobbin and Kelly 2006), we examine the impact of workplace structures and policies on gendered preferences for organizing work and family life. Thus, our research complements studies that focus on gendered processes within organizations by addressing how gendered workplaces fuel a key “supply-side” process that contributes to gender inequality in the labor market as well as in the family. Ultimately, our findings contribute new insights to long-standing theoretical debates about the institutional- and individual-level factors that underlie persistently gendered patterns of paid and unpaid work in American society.

Gendered Preferences, Gendered Institutions

While there is considerable evidence that “demand side” processes, such as employer discrimination, contribute to unequal outcomes for men and women in hiring, promotion, and pay (Castilla 2008; Correll, Benard and Paik 2007), “supply side” processes have garnered substantial attention and debate in recent years from scholars and the public alike (Belkin 2003; Fernandez and Friedrich 2011; Sandberg 2013; Slaughter 2012; Stone 2007). For instance, despite an overall rise in women's representation in professional and managerial roles (Percheski 2008), women (especially those with children) remain substantially less likely than men to pursue the most competitive and time-intensive (male-typed) professional career tracks. And, those who do are more likely to leave these careers midstream, either to be at home full-time or to switch to a more “part-time friendly” occupation (which is typically female-dominated) (Cha 2010; 2013; Stone 2007).

This “opt out” phenomenon is often understood in the public discourse to be a reflection of stable differences between men's and women's work-family preferences. Often rooted in gender-essentialist beliefs about men's and women's hard-wired differences (for a discussion, see Charles and Bradley 2009; England 2010), popular perspectives invoke a logic of choice: men prefer more competitive work environments, whereas women prefer less demanding work environments and/or “choose” to return home because they value the comforts of home and family (see Belkin 2003).

Although many women who “opt out” stand by their choice to forego their career as something they prefer to do for the benefit of their families, many gender scholars have argued that these seemingly gender-traditional preferences are actually formed under a high level of institutional constraint. This is largely because modern work organizations are still premised on an ideal (i.e., male) worker, an individual who can unconditionally commit to a firm because he has few domestic responsibilities (Acker 1990; Jacobs and Gerson 2004; Williams 2001), and cultural ideologies increasingly praise an unyielding commitment to work and “intensive” parenting styles (Blair-Loy 2003; Hays 1998). Workplace practices that prize long hours as a signal of unwavering commitment disproportionately disadvantage women because widely shared cultural beliefs about gender (often implicitly) prescribe caregiving as a woman's responsibility, regardless of her income or career status (Correll et al. 2007; Potuchek 1997; Tichenor 2005).

To date, much of the scholarship and public discourse in this area has focused on the work-family challenges specific to professional and managerial workers. Research suggests, however, that gendered institutions are similarly, if not more, constraining for working class men and women, who, for instance, typically have less flexibility and control over their schedules and may have to work multiple jobs to earn an adequate wage to support their families (Presser 2003; Williams 2006). Thus, the constraining nature of workplace demands for balancing work and family life likely span across the education, class, and occupational spectrum.

Gerson's (2010a) study builds on these arguments by specifying the ways in which institutional constraints may affect work-family preferences. In interviews with men and women between the ages of 18 and 32, she finds that the current institutional logics of “greedy” workplaces are incompatible with “hard-won desires for egalitarian relationships” (p. 220). While both men and women would ideally prefer to be in a long-term, egalitarian relationship where both partners contribute equally to earning and caregiving (what Gerson (2010b) refers to as individuals’ “Plan A”), many doubt that this ideal preference is attainable given the reality of social and economic conditions that demand long hours for successful employment and successful parenting. As a result, men's and women's fallback plans (what Gerson (2010b) refers to as individuals’ “Plan B”) differ considerably from their ideal preferences. For men, concerns about workplace pressures and the expectations of some men that women will serve as the primary caretaker for any future children lead them to prefer a “neotraditional” fallback plan. These arrangements retain a traditional gender boundary in which the man is the primary labor market earner and his wife is the primary caregiver (regardless of her employment status or income level). By contrast, women express concern about the instability and risk that traditional work-family models could pose for them and, as a result, stress a fallback plan of self-reliance. These women prefer to be personally autonomous and financially independent, even if that means foregoing a lifelong relationship (Gerson 2010a). To the extent that they desire children, they tend to decouple marriage from motherhood and to reject the selfless ideology of traditional mothering.1

Gerson (2010a) also finds that men's and women's fallback plans may differ somewhat by class background. Despite having less advantageous employment prospects, the women from working class backgrounds in her study were more likely to stress self-reliance and less likely to stress a neotraditional fallback plan than their middle- and upper-middle class counterparts. Moreover, working class men were slightly less likely to fall back on neotraditional arrangements than their more advantaged male counterparts. This contrasts with some prior work suggesting that working class men tend to hold a more gender-traditional ideology (Deutsch 1999; Williams 2010; Wilkie 1993).

Taken together, this literature suggests that institutionalized constraints in the workplace, which are generally unsupportive of individuals with family responsibilities, substantially affect men's and women's preferences regarding work and family arrangements. Specifically, unsupportive institutions amplify gendered patterns in work-family preferences because they effectively limit a couple's ability to equally share earning, housework, and caregiving, whereas supportive institutions mitigate such gender differences because they make egalitarian arrangements a more feasible option. Disentangling the extent to which workplace and policy structures affect men's and women's stated work-family preferences, independent of otherwise stable, deep-seated beliefs at the individual-level has proven difficult in prior research. Therefore, to advance the literature in this area and gain traction on this complex set of issues, we draw on original experimental data. Before describing our methodological approach in detail, however, we first turn to the literature on work-family policies to provide preliminary reasoning behind our argument that certain kinds of policy arrangements can have the power to “de-gender” individuals’ preferences for balancing formal employment, household work, and caregiving.

Policy Promises and Caveats

If institutions are arguably to blame for stubbornly gendered work-family patterns, then which kinds of changes in institutions could shift individuals’ preferences and decision-making? Many work-family scholars advocate policies that are more supportive of working parents, such as subsidized childcare, paid family leave, flexible scheduling and schedule control (Gornick and Meyers 2003; 2009a; Jacobs and Gerson 2004; Kelly, Moen and Tranby 2011). In the United States, access to these kinds of policies is particularly limited. For instance, national policies offer minimal childcare assistance and a limited duration of unpaid leave after the birth of a child, a level which is lower than all other industrialized nations as well as many developing nations (Gerstel and Armenia 2009; Gornick and Meyers 2003; 2009a). Moreover, although part-time work is more common in female-dominated occupations, these occupations actually offer less scheduling flexibility than others (Glass and Camarigg 1992; Weeden 2005). And, even elite workers who do have greater access to paid leaves and flexible workplace practices through their employers are often reluctant to make use of them for fear of the negative employment consequences that can arise from violating the cultural norm of having an unwavering commitment to work (Fried 1998; Hochschild 2001; Perlow and Kelly 2014; Turco 2010). Indeed, there is evidence that individuals are critically aware of the fact that workers who request flexibility from their employer are stigmatized, so much so that they are likely to believe that others view such workers more negatively than they do themselves (Munsch, Ridgeway and Williams 2014). This concern, which fuels the reluctance to take advantage of supportive work-family policies, is particularly acute for men who may have a (well-founded) sense that requesting leave or flexible hours would also undermine their masculine credibility among coworkers and managers (Butler and Skattebo 2004; Rudman and Mescher 2013; Vandello et al. 2013).

Cross-national studies suggest, however, that universal policies (i.e., policies that are available to all workers, regardless of their income) may nevertheless influence men's and women's work-family decisions (see Hegewisch and Gornick 2011 for a review). For instance, women's full-time employment is particularly high in countries such as Sweden, which offers paid leaves and publicly funded childcare (Mandel and Semyonov 2006). Although policy change in general has had less of an impact on men's behavior than women's, studies find that when countries extend parental leave to men, particularly through “use it or lose it” incentives, men do increase their contributions in the home (Hook 2006). Prior research also suggests that when men take advantage of employer-provided policies, they engage in a greater share of traditionally female-typed household tasks (Estes, Noonan and Maume 2007). Policies that allow for more flexible work hours – such as regulations on total working time, increased worker autonomy over their schedules, and/or more opportunities to work from home without the risk of a penalty – are also considered particularly beneficial for balancing work and family time, especially as children get older (Gornick and Meyers 2009a; Lyness et al. 2012). Though the effectiveness of particular policies and policy configurations remain a topic of debate,2 the underlying goal of these work-family policies – whether implemented by states, employers, or a combination of both – is to reduce institutional constraints on working parents and to enable couples to achieve egalitarian, dual-earner, dual-caregiver arrangements if that is what they prefer (Fraser 1994; Gornick and Meyers 2009b).

Nevertheless, some scholars remain skeptical of the extent to which supportive work-family policies can create widespread change in the gendered division of labor in light of resilient norms and expectations regarding gender, work, and family. For instance, Blair-Loy (2003) argues that policies will be ineffective “without a transformation of the work-devotion culture currently devouring American managers and executives” (p. 18), which involves big rewards for long hours at work and internalized beliefs about what kinds of pursuits make a life worthwhile. Others argue that policy changes in workplaces may be ineffective and possibly even detrimental without fundamental changes to the deep investments people have in gender, such as the power and advantages of men's current positions, the cultural dominance of intensive mothering, and the freedom to express what are often thought of as essentially different and “gendered selves” (Charles and Bradley 2008; MacDonald 2009; Orloff 2009).

Furthermore, it is possible that these types of work-family policies would have uneven effects across the class structure. On the one hand, policy and discourse around workplace flexibility has been largely focused on employer-supported policies for salaried, professional positions, and as a result, these policies may not be relevant or helpful for, hourly employees (see Lambert, Haley-Lock and Henly 2012). Shalev (2009) also suggests that the public provision of childcare would factor little into working class women's work-family decisions because working class women traditionally rely more on extended family for childcare provision. On the other hand, childcare costs as a percentage of income are disproportionately higher for lower income families (Williams 2010), and working class women's employment interruptions often result from failures in their fragile care networks (Damaske 2011). Moreover, because the parenting culture of “concerted cultivation” (Lareau 2003) is prevalent among the middle and upper-middle class, class-privileged women may be the ones to discount publicly provided childcare because they prefer options like private nannies who are better substitutes for home-based intensive parenting (MacDonald 2009). Therefore, the effects of these policies may affect work-family preferences differently across the social classes, but the effect could go in either direction.

Remaining cognizant of these debates, we suspect that universal access to policies along the lines of what Gornick and Meyers (2003; 2009a) term a “dual-earner/dual-carer” model—namely, paid parental leave, subsidized childcare, and workplace flexibility—are likely to promote more egalitarian work-family ideals among young, unmarried, childless men and women across the social class spectrum because, despite variability in work experiences and parenting norms, they will more often than not reduce the salience of gendered structural constraints in modern workplaces. At the same time, access to supportive policies alone may not fully eliminate gendered patterns, given the resilience of shared beliefs and expectations about gender and work in American culture. Because shared gender beliefs still prescribe women greater responsibility for caregiving and men greater responsibility for earning, work-family policies designed to restructure employer expectations around earner-caregiver employees are more directly relevant to women's experiences than men's. As a result, men may be less likely to recognize the ways that the availability of such policies could broaden their own options for organizing work and family responsibilities.

Empirical Predictions

The two theoretical claims articulated above – that both men and women would ideally prefer egalitarian relationships if it were a possible option and that institutional arrangements, such as supportive work-family policies, have the power to further shape these relationship preferences – have been particularly difficult for researchers to tease apart because of the endogeneity between individual preference formation and institutional environments. Extant research on the association between work-family policies and work-family preferences and decision-making relies on interview or cross-sectional survey data, often across national contexts (e.g., Hook 2006; Mandel and Semyonov 2006). While these studies provide important correlational insights, it remains an open question as to whether supportive policies have an independent effect on men's and women's work-family preference formation. Thus, our research contributes to the existing literature by providing, to our knowledge, the first estimate of the causal effect of perceived structural dynamics – specifically, the presence or lack of an egalitarian relationship as an option at all, and the presence or lack of supportive work-family policies – on relationship preferences. While we are not able to examine the consequences of respondents’ lived experiences under different institutional constraints, we believe that our research design has the ability to offer important insights about how differing structural dynamics shape the way that individuals form their relationship preferences.

In this study, we use a survey-experimental design that allows us to address these concerns about endogeneity. By randomly assigning respondents to conditions with different levels of institutional constraint, we eliminate concerns that observable or unobservable differences between respondents, such as the family environment in which they grew up or the ways that individuals may select into particular work environments, are driving our findings. We utilize two experimental manipulations that offer the rare opportunity to examine men's and women's preferred work-family arrangements under different institutional conditions that are exogenously determined. First, we evaluate Gerson's argument by experimentally manipulating the response choices that participants are offered when asked about the ideal structure of their future work and family life. Consistent with Gerson (2010a), we expect that gender differences in men's and women's preferred work-family arrangements will be greatest when an egalitarian earner-caregiver arrangement is not offered as a response option (i.e., the “Fallback Plan” condition, where there is a high level of institutional constraint). Specifically, we posit that when no egalitarian option is available, men will be most likely to prefer a neotraditional arrangement, whereas women will be most likely to prefer a “self-reliant” strategy. That is, women will stress a preference for personal and financial independence, regardless of whether or not they have a lifelong relationship. However, the majority of men and women will prefer egalitarian arrangements when they are made available as an option (i.e., the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition, where there is a moderate level of constraint).

Second, we investigate whether supportive workplace policies further affect men's and women's ideal work-family preferences by asking a randomly assigned group of participants to express their ideal work-family arrangements under the assumption that egalitarianism is an option and there is full, unconditional access to policies that are supportive of working parents (i.e., the “Supportive Policies” condition, where there is low institutional constraint). Specifically, we expect that making supportive policies (i.e., paid leave, subsidized childcare, and flexible workplace practices) salient will enable men's and women's preferred work-family arrangements to come into even sharper relief. That is, respondents will be most likely to prefer egalitarian work-family arrangements under conditions where all workers have access to policies that support a “dual earner/dual carer” model (Gornick and Meyers 2003; 2009a) than when no such policies are made salient. However, we expect that the effect of supportive policies will be stronger for women because, in light of ongoing gendered expectations about who is responsible for household work and caregiving, they are the ones who stand to disproportionately benefit from these policies. Moreover, men have fewer incentives to take advantage of such policies given that they may face negative social repercussions for doing so.

Third, we analyze each of these patterns separately for respondents who are and who are not on a college-educated employment trajectory, which we use as a rough proxy for social class.3 As discussed, there exists in the literature contradictory evidence about the extent of differences by social class in the overall distribution of work-family preferences. Moreover, there is an important debate over how much social class and employment circumstances affect individuals’ perceptions and experiences of institutional constraints in the workplace. Therefore, it is not clear whether the removal of institutional constraints, particularly through supportive work-family policies, would have stronger, weaker, or similar effects for these two groups. For these reasons, we remain largely agnostic about the extent and form of the effects of educational background on our outcome variables.

Data & Methods

To address the hypotheses articulated above, we draw on original survey-experimental data. The survey experiment was fielded by a survey research company, formerly Knowledge Networks (now called Gfk), that maintains a national probability-based online panel of respondents that is representative of the United States population. The Knowledge Networks panel was built using random-digit dialing and address-based sampling methods. Households selected for the panel who need computers or access to the Internet are provided with those resources. Thus, while our survey was administered online, the sample was not limited to computer and Internet users.

Given that our hypotheses center on the future relationship preferences of young men and women, our sample was limited to respondents between 18 and 32 years old. Additionally, we only included unmarried individuals without any children.4 Because individuals who are married or have children have likely already negotiated balancing work and family pressures, their preferences about relationship structures may be heavily influenced by their current experiences and thus present a different set of constraints than we are focused on here. Additionally, while our sample includes respondents of all sexual orientations, we do not have information about whether an individual identifies as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgendered (LGBT).5 Importantly, though, the random assignment of respondents across experimental conditions prevents any systematic differences between LGBT and non-LGBT individuals from biasing our findings.

The survey was fielded between August 3, 2012 and August 9, 2012.6 The completion rate for the survey was 44.6 percent, which is generally consistent with Knowledge Networks surveys and significantly higher than non-probability, opt-in, web-based panels where survey completion rates are generally between two and 16 percent (Knowledge Networks 2012). Importantly, because the individuals who were contacted to participate in the survey, but did not complete the survey, are part of Knowledge Networks’ on-going panel of respondents, detailed demographic and background information is available on the non-responders. This information about the individuals who did not respond to the survey is incorporated into a weight created by Knowledge Networks to adjust the sample for non-response and representativeness of the U.S. population. We use these weights in all of the analyses presented below (for more information on the design of the weights, see Knowledge Networks (2012)).7

Experimental Design

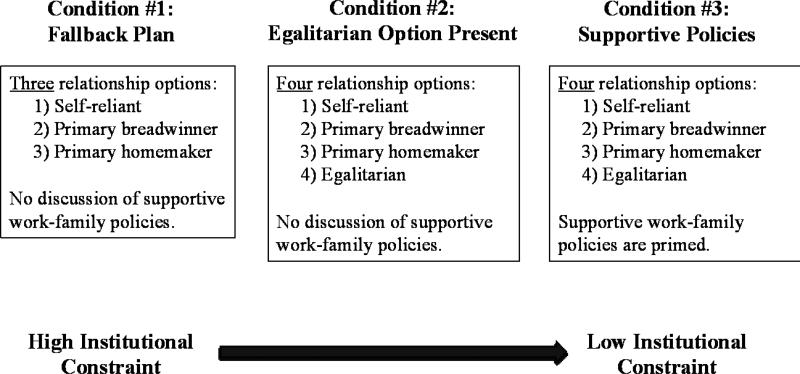

We conducted a between-subjects experimental study with three experimental conditions, summarized in Figure 1.8 The first condition (Condition #1: Fallback Plan) asked respondents to report their relationship structure preference (i.e., how they would like to share work and household responsibilities with their future spouse or partner) and provided them with three options. The first option category reflects a “self-reliant” preference. Specifically, respondents indicate that they would prefer to maintain personal independence and focus on a career, even if that would mean forgoing marriage or a life-long partner. The content and framing of this option closely parallels Gerson's (2010a) “self-reliant” construct (p. 105). The second and third options reflect neotraditional and counter-normative arrangements (depending on the respondent's gender) by asking whether one would prefer to be primarily responsible for either a) breadwinning or b) managing the household (which may include housework and/or caregiving). In the “primary breadwinner” option, the respondent would be primarily responsible for financially supporting the family, whereas his/her spouse would be primarily responsible for managing the household; in the “primary homemaker/caregiver” option the respondent would be primarily responsible for managing the household, whereas his/her spouse would be primarily responsible for financially supporting the family. Importantly, these options do not preclude dual-earner arrangements. For instance, the “primary breadwinner” category reflects a respondent's preferred level of responsibility for earning relative to his or her spouse. Thus, a respondent who selects the primary homemaker/caregiver option could also plan to work outside the home.

Figure 1.

Experimental Design

This first experimental condition is designed to capture respondents’ fallback relationship structure preferences, their preferences under conditions of high institutional constraint. Respondents were unable to select an egalitarian option – creating conditions similar to those under which Gerson's respondents expressed their “fallback positions” (Gerson 2010a; 2010b). Moreover, there is no information provided to respondents about policies that would support their ability to balance work and family life. This leaves respondents to state their preferences under a level of institutional constraint that is similar to the current policy environment in the United States.

The second experimental condition (Condition #2: Egalitarian Option Present) presented respondents with the same question as Condition #1 – asking them for their relationship structure preferences – but added an egalitarian option to the response categories. Specifically, this option allowed the respondent to indicate if they would prefer an egalitarian relationship where work and family tasks would be shared equally between spouses. This experimental condition is therefore less constrained than the first and corresponds to the ideal relationship structure preferences that Gerson's (2010a; 2010b) respondents expressed. However, similar to the first condition, in Condition #2 we do not provide respondents with any information about policies that support work and family life. Thus, there is still a level of institutional constraint in the second experimental condition.

Our final experimental condition (Condition #3: Supportive Policies) offered respondents the same relationship structure preferences as were offered in the second condition. However, in this condition, we also provided respondents with information about supportive work-family policies in the framing of the question. Respondents were told to imagine that there were supportive policies in place to ease the challenges associated with work-family balance. Following Gornick and Meyers’ (2009a) earner-caregiver policy model, they were told to imagine that all workers had access to paid family leave, subsidized childcare, and flexible work options (such as the opportunity to work from home one day per week). To ensure that our results are not confounded by the possible influence of attitudes toward government spending or heterogeneous prior or current exposure to employer-based policies, the “Supportive Policy” condition does not specify whether these policies are made available by governments or by employers. Thus, Condition #3 is designed to limit the influence of institutional constraints on respondents’ stated preferences as much as possible by providing an egalitarian option and indicating that supportive policies are in place (see Appendix A for the exact wording of the experimental prompts).9

Since respondents are randomly assigned to each of the experimental conditions, our research design enables us to estimate the causal effect of each of our treatments without including control variables in our statistical models (Mutz 2011). Thus, we do not adjust for respondent characteristics in the models presented below. The results we present, however, are robust to the inclusion of a large set of demographic, economic, and ideological control variables, including the respondent's level of desire to have children and a standard gender ideology scale (results available upon request). The robustness to gender ideology, in particular, gives us added confidence that our findings pertaining to the effects of institutional constraint are not being driven by prescriptive beliefs at the individual-level regarding how men and women ostensibly ought to organize their work and family responsibilities.

Key Variables

The primary dependent variable in our analysis is the relationship structure preference selected by respondents (e.g., egalitarian, self-reliant, etc.). We code selections of the “primary breadwinner” option as neotraditional for men and counter-normative for women. We code selections of the “primary homemaker/caregiver” option as counter-normative for men and neotraditional for women. The primary independent variable in our analysis is the experimental condition to which respondents were randomly assigned. Additionally, we analyze the responses of male and female respondents separately in our analyses given that previous research has found important gender differences in relationship structure preferences (Gerson 2010a). Moreover, because we expect variation by respondents’ education level, we examine responses separately for respondents with at least some college-level education and those with a high school education or less. Since many of our respondents are between 18 and 24 years old, prime age for being enrolled in college, many of the respondents reporting “some college” will likely complete college in few years. Thus, their career and relationship expectations and aspirations are likely similar to those respondents who have completed college. We present weighted descriptive statistics for the key demographic characteristics of our sample in Table 1.10

Table 1.

Weighted Descriptive Statistics of Respondent Characteristics

| Proportion/Mean | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.431 | 0 | 1 |

| Completed at Least Some College | 0.598 | 0 | 1 |

| Age (In Years) | 23.1 | 18 | 32 |

| Race/Ethnicity: | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 0.655 | 0 | 1 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 0.091 | 0 | 1 |

| Other, Non-Hispanic | 0.047 | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic | 0.201 | 0 | 1 |

| Two or More Races | 0.018 | 0 | 1 |

| Household Income (Median) | $67,500 | $2,500 | $175,000 |

| Currently Working | 0.62 | 0 | 1 |

| Southern Resident | 0.337 | 0 | 1 |

| Sample Size | 329 |

Notes: Population weights were used to produce descriptive statistics. Listwise deletion was used to deal with missing data.

Manipulation Check

At the end of the survey, respondents were asked: “Which of the following statements is accurate about the first question you answered on this survey?” Respondents were then offered three options, one of which indicated that they were told nothing about supportive policies and two that contained information about work-family policies. As expected, we find that respondents in the “Supportive Policies” condition are significantly less likely than respondents in the “Fallback Plan” and “Egalitarian Option Present” conditions to report receiving no information about work-family policies (|z| = 5.62, p < .001). However, there were some respondents in each condition who did not accurately recall the manipulation. It is unclear how to interpret the findings for these respondents because if they did not notice the manipulation, it could not have meaningfully affected their responses. Therefore, we follow the common practice among experimentalists of limiting our analysis to respondents who accurately recalled the manipulation (see e.g., Simpson, Willer and Ridgeway 2012). Our final analytic sample includes 329 respondents (sample sizes range from 84 to 132 respondents in each experimental condition).11 After presenting our main findings, we test for the robustness of our results to the decision to exclude respondents who did not pass the manipulation check.

Results

Our analysis proceeds in two parts. First, we discuss the differences between respondents’ preferences in the “Fallback Plan” and “Egalitarian Option Present” conditions (“high” versus “medium” constraint) and examine gender and education differences in each of these conditions. Second, we examine how priming supportive work-family policies (“low” constraint) shapes respondents’ relationship structure preferences, compared to not having any policy prime, and how this effect varies by gender and education.

Preferences Under “High” Versus “Medium” Constraint

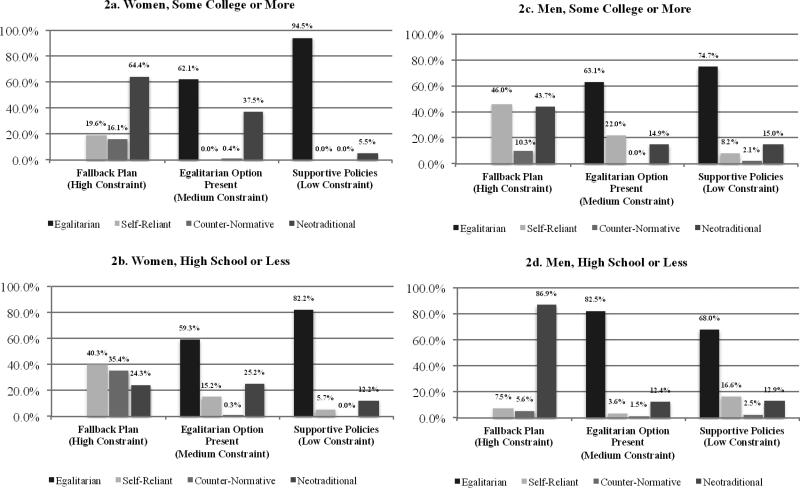

We begin our analysis by examining men's and women's fallback relationship structure preferences, which are their preferences under conditions of high institutional constraint. Figure 2 presents respondents’ relationship structure preferences across experimental conditions, broken down by gender and education. Higher educated women's “Fallback Plan” preferences are presented in the upper-left cluster of bars (Figure 2a). Here, we see that 64.4 percent of women with higher levels of education gravitate towards a neotraditional relationship structure under high institutional constraint. For women with less education (Figure 2b), however, their preferences are relatively evenly distributed across the self-reliant (40.3%), counter-normative (35.4%), and neotraditional (24.3%) options. A bivariate logistic regression model indicates that higher educated women have more than five times the odds of less educated women of selecting the neotraditional option under conditions of high constraint (OR = 5.62, p < .05).12

Figure 2.

Distribution of Male and Female Relationship Structure Preferences, by Education

Source: Original survey-experimental data collected via Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences.

We also find that men's “Fallback Plan” preferences differ substantially by education level. Among more highly educated men (Figure 2c), 46.0 percent selected the self-reliant option, 43.7 percent selected the neotraditional (i.e., primary breadwinner) option, and 10.3 percent selected the counter-normative option. Among less educated men (Figure 2d), the vast majority (86.9%) opted for the neotraditional arrangement, where they would be the primary breadwinner. These differences by education are highly statistically significant for men (weighted chi-square square test: F(1.93, 154.45) = 8.46, p < .001).

Finally, we compare the “Fallback Plan” preferences of men and women. There is no overall difference in these preferences for men and women on a college career track (weighted chi-square square test: F(1.77, 136.56) = 1.26, p = .29). It is important to note, though, that this lack of a statistically meaningful finding indicates that more highly educated men's and women's fallback preferences actually represent a highly gendered (i.e., neotraditional) arrangement agreed upon by men and women. Our findings also indicate, however, that there are statistically significant gender differences in the “Fallback Plan” preferences of lower educated men and women (weighted chi-square square test: F(1.94, 98.66) = 11.22, p < .001).

Next, we turn to the medium constraint condition (which corresponds to the ideal preferences expressed by Gerson's (2010a) participants). Here, respondents were provided with the option of selecting an egalitarian relationship structure. A majority of women, 62.1 percent of higher educated women (Figure 2a) and 59.3 percent of lower educated women (Figure 2b), selected the egalitarian option when it was provided. Meanwhile, 63.1 percent of men with some college education (Figure 2c) and 82.5 percent of men with a high school education or less (Figure 2d) indicated that they would ideally like to have an egalitarian relationship structure. Using logistic regression techniques, we find no evidence in our data that the odds of a respondent desiring an egalitarian relationship varied in a meaningful way by gender or education (results available upon request). This finding – that a majority of men and women, across education groups, ideally prefer egalitarian relationship structures – is consistent with the results presented in Gerson's (2010a) work.

Importantly, a sizable minority (37.5%) of higher educated women selected a neotraditional option under conditions of medium constraint. Lower educated women who did not select the egalitarian option were split between the self-reliant (15.2%) option and the neotraditional (25.2%) option. Higher educated men who did not opt for the egalitarian option generally selected the self-reliant (22.0%) and neotraditional (14.9%) options. However, weighted chi-square tests do not provide evidence that women's (F(2.09, 112.76) = 1.46, p = .24) or men's (F(2.33, 130.42) = 1.81, p = .16) preferences differed in statistically significant ways by education level in the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition.

While it would be interesting to statistically compare the distribution of responses for respondents in the “Fallback Plan” and “Egalitarian Option Present” conditions, there is no straightforward way to do so. The experimental design presented respondents with a different number of un-ordered response options in these conditions. Thus, the distribution of responses in these experimental conditions is necessarily different due to the research design. What is clear from descriptively examining the results, however, is that respondents’ preferences are highly gendered in the “Fallback Plan” condition. When some constraint is removed, though, in the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition, men and women at all levels of education prefer an egalitarian relationship structure.

Preferences Under “Medium” Versus “Low” Constraint

We now move on to examine whether priming respondents to imagine supportive work-family policies influences respondents’ relationship structure preferences. Here, we attempt to simulate a condition of low institutional constraint. First, we examine how supportive work-family policies shape women's relationship structure preferences. Among higher educated women, 94.5 percent indicated that they would ideally structure their relationship in an egalitarian manner when supportive policies are primed. This is more than 30 percentage points higher than in the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition, which did not include supportive policies. At the same time, only 5.5 percent of women with at least some college education selected the neotraditional (i.e., primary homemaker, secondary earner) option when supportive policies were primed, compared to 37.5 percent in the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition. Among lower educated women, 82.2 percent opted for an egalitarian relationship in the “Supportive Policies” condition, a more than 20 percentage-point increase from the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition. Only 12.2 percent of lower educated women selected the neotraditional option when supportive policies were primed.

Table 2 examines whether the effects of the supportive policy prime were statistically meaningful for women's relationship structure preferences. Model 1, a logistic regression model, examines the effect of the supportive work-family policy prime on women's likelihood of selecting an egalitarian relationship. The positive and statistically significant coefficient for the supportive policies variable indicates that when women were primed with supportive work-family policies, their odds of selecting an egalitarian relationship were more than five times higher (exp(1.63) = 5.10) than when no supportive policies were primed. Model 2 examines whether this finding is moderated by women's level of education by including an interaction between being in the supportive policies condition and women's education level. The interaction term is not statistically significant, suggesting that education does not play a moderating role.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Models of the Consequences for Women of Supportive Policies and Education on Relationship Structure Preferences

| Egalitarian Relationship | Neotraditional Relationship | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Supportive Policies | 1.629* | 1.152 | −1.593* | −0.889 |

| (0.657) | (0.835) | (0.761) | (0.977) | |

| Higher Education Level | 0.363 | 0.120 | 0.291 | 0.575 |

| (0.666) | (0.789) | (0.717) | (0.830) | |

| Supportive Policies X Higher Education | -- | 1.198 | -- | −1.445 |

| -- | (1.417) | -- | (1.507) | |

| Constant | 0.248 | 0.375 | −0.923* | −1.086* |

| (0.421) | (0.461) | (0.462) | (0.524) | |

| n | 91 | 91 | 91 | 91 |

Notes: Log-odds are presented. Standard errors in parentheses. Weights used in all models. Listwise deletion used for missing data.

p < .05

** p < .01

*** p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

In Model 3, we turn to the effect of supportive policies on the odds of women selecting a neotraditional relationship structure. We see a large, negative, and statistically significant coefficient for the supportive policies variable, indicating that women in the “Supportive Policy” condition are less likely than women in the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition to select a neotraditional relationship. Model 4 shows no evidence that this effect varies by education level.

We now turn to how supportive work-family policies shape men's relationship structure preferences (Figure 2). Among more highly educated men, 74.7 percent indicated that they would prefer an egalitarian relationship when supportive work-family policies were primed, compared to 63.1 percent in the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition (Figure 2c). A logistic regression model indicates that this difference is not statistically significant. Next, in Figure 2d, we see a slight decrease in the proportion of lower educated men who would prefer an egalitarian relationship between the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition (82.5%) and the “Supportive Policy” condition (68.0%), but again this difference is not statistically meaningful.

In addition to the logistic regression models presented above, which examine the effect of different experimental conditions on whether a respondent selected a particular relationship structure preference compared to all of the other relationship structure options, we also estimated a series of multinomial logistic regressions, which jointly examine the effect of the policy prime on the full set of respondents’ relationship structure preferences. The results from these analyses, which are presented and discussed in Appendix B, are highly consistent with those presented above. However, because multinomial logistic regressions can be fairly cumbersome to present, interpret, and discuss, we do not focus on them here.

Together, these findings provide compelling evidence that supportive policies play an important role in shaping relationship structure preferences, but that those consequences tend to be concentrated among women, regardless of their level of education. We do not find consistent effects of the supportive policy prime on the ways that men would ideally like to structure their future relationships. Below, we examine the robustness of these findings and then conclude by discussing the implications of our results for research on gender, work, and social stratification.

Robustness Checks

In this section, we examine the sensitivity of our findings to various analytic decisions. First, we evaluate the robustness of the findings to the decision to exclude respondents who did not accurately answer the manipulation check item regarding the supportive policy prime. While limiting our analytic sample in this way ensures that the responses we analyze are driven by the experimental manipulations, it is possible that this approach introduces bias into our sample. If the respondents who accurately received the manipulation check are different – on observable or unobservable characteristics – than the respondents who failed the manipulation check, then limiting our analytic sample in this way could lead to biased estimates.

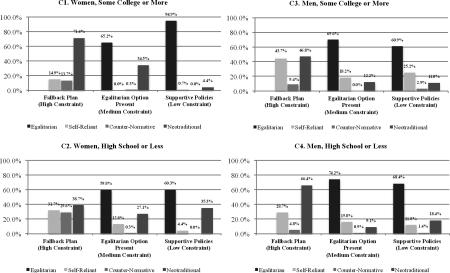

The two central findings from the analyses presented above are: 1) in the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition, a majority of men and women selected an egalitarian relationship and this does not vary by gender or education; and 2) there are strong, positive effects of the supportive policy prime on the odds of women selecting an egalitarian relationship and negative effects of the supportive policy prime on the odds of women selecting a neotraditional relationship structure. Here, we re-examine these key findings using the full sample of respondents, including those who did not accurately answer the manipulation check item. In Appendix C we present the descriptive distributions of relationship structure preferences by gender and education for the full sample of respondents.

First, when including all respondents, patterns of results for individuals’ preferences under high and moderate levels of constraint are similar to those presented above. In particular, the majority of respondents across gender and education groups selected an egalitarian option when that option was provided as a response category. Logistic regression models further indicate that the proportion of respondents selecting an egalitarian relationship in the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition does not vary by gender or education (results available upon request).

Second, we examine possible differences in the effects of the supportive policy prime. The descriptive patterns of results are similar to those in the original analysis for each gender-education group, with the exception of women with a high school education or less. Model 1 in Table 3 shows the logistic regression model examining how supportive policies affect women's odds of selecting an egalitarian relationship structure preference. While the coefficient for supportive policies is positive, it is not statistically significant. Model 2, which includes the interaction between women's education level and being in the “Supportive Policies” condition, indicates that the consequences of supportive policies differ for higher and lower educated women in the full sample. Consistent with our prior analysis, supportive policies have a positive effect on higher educated women selecting an egalitarian relationship (OR = 9.87, p < .05). Unlike our prior analysis, however, we do not find that supportive policies influence lower educated women's preferences for an egalitarian relationship (OR = 1.02, p = .98).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models of the Consequences for Women of Supportive Policies and Education on Relationship Structure Preferences (Full Sample)

| Egalitarian Relationship | Neotraditional Relationship | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Supportive Policies | 0.768 | 0.0197 | −0.594 | 0.380 |

| (0.552) | (0.689) | (0.593) | (0.735) | |

| Higher Education Level | 1.079 | 0.229 | −0.729 | 0.345 |

| (0.562) | (0.734) | (0.596) | (0.758) | |

| Supportive Policies X Higher Education | -- | 2.272* | -- | −2.812* |

| -- | (1.124) | -- | (1.197) | |

| Constant | −0.0145 | 0.399 | −0.441 | −0.988* |

| (0.391) | (0.428) | (0.393) | (0.463) | |

| n | 133 | 133 | 133 | 133 |

Notes: Log-odds are presented. Standard errors in parentheses. Weights used in all models. Listwise deletion used for missing data. Analyses include respondents who failed the manipulation check.

p < .05

** p < .01

*** p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Model 3 in Table 3 investigates the consequences of supportive policies for women's likelihood of selecting a neotraditional relationship structure. Again, there is no meaningful main effect of supportive policies detected here. In Model 3, however, we include an interaction term between women's education level and the supportive policy prime, which has a statistically significant and negative coefficient. This indicates that, for higher educated women, supportive policies are consistently associated with lower odds of selecting a neotraditional relationship (OR = .09, p < .05), whereas there is no effect of supportive policies on the odds of lower educated women selecting a neotraditional relationship structure (OR = 1.46, p = .61). Thus, when analyzing the full sample, the effects of supportive policies for higher educated women mirror the findings presented in the analytic sample above, but we encounter divergent findings for women with lower levels of education.

One possible explanation for the different findings for lower educated women may be that the lower educated women who passed the manipulation check are different than the lower educated women who failed the manipulation check. To test for this possibility, we examined whether the lower educated women who “failed” the manipulation check were any different from the lower educated women who “passed” the manipulation check in terms of gender ideology, desire to have children, political ideology, age, household income (logged), employment status, or region of residence. We do not find any evidence that this is case. Thus, at least on observables, lower educated women who passed the manipulation check look similar to lower educated women who failed the manipulation check. For this reason, we are inclined to cautiously interpret the findings that are limited to female respondents who accurately answered the manipulation check – those presented in the main section of the article – as more accurately reflecting the effects of supportive policies on women's relationship structure preferences. However, future research would be well served to further investigate how education and social policies interact in the production of women's relationship structure preferences.

As a second robustness check, we examine variation in our findings by respondents’ age. Following Gerson (2010a), our sample contains unmarried, childless men and women between the ages of 18 and 32. Yet, it is possible that individuals in their early twenties may be less aware of the constraints of current workplaces than individuals in their early thirties, leading to variation in the effects of the policy prime by respondent age. To evaluate this possibility, we conducted three analyses examining whether the effect of the supportive policy prime on women's preferences for an egalitarian relationship (Model 1 from Table 2) varies by age. First, we tested for an interaction between a linear age term and the variable for whether the respondent received the supportive policy prime. Second, in a separate model, we interacted a dichotomous age variable (older than 25 versus 25 or younger) with whether the respondent received the supportive policy prime. In neither case was the interaction term statistically significant. Third, the coefficient for the effect of the supportive policy condition on women's preferences was similar when we ran the model while sub-setting our data by different age groups. Therefore, it does not appear that there is significant variation in our findings by respondents’ age.

Discussion & Conclusion

How would young, unmarried, childless men and women ideally like to structure their future relationships to balance the demands of work and family life? When institutional constraints render those ideal preferences unattainable, what becomes of men's and women's relationship structure preferences? And, what role do policies that support work-family balance play in shaping such preferences? To date, answering these questions has been challenging. Differentiating between individuals’ ideal and fallback relationship structure preferences has remained largely in the realm of qualitative research, leaving open questions about the generalizability of these findings. And, identifying the direct effect of supportive work-family policies in shaping relationship structure preferences has proven elusive given the endogeneity concerns that arise between policy interventions and preferences. Using a survey-experimental methodology conducted on a national probability sample of young, unmarried, childless men and women, we begin to fill these gaps in the literature.

Our first main finding is that the majority of the young men and women in our study, regardless of their education level, prefer an egalitarian relationship structure when that option is available to them. This result is consistent with Gerson's (2010a) work. We also find evidence that young men's and women's preferences are strongly gendered when they face a high level of institutional constraint (the “Fallback Plan” condition), but that these patterns vary by education level. The lower educated men and women in our sample also demonstrate fallback relationship structure preferences that align closely with Gerson's (2010a) findings: women without any college education largely prefer either the self-reliant or primary breadwinner option, whereas their male counterparts overwhelmingly prefer a neotraditional arrangement.13

Our findings regarding respondents’ fallback preferences also resonate with prior research on the intersecting dynamics of gender and class in the work-family domain. As the need for two earners in a household has become increasingly necessary for middle- and upper-middle class families in recent decades, neotraditional arrangements enable well-educated women to simultaneously live up to the expectations of intensive mothering without substantially sacrificing their own financial stability: the long-term employment prospects of their potential spouses are good and their own employment opportunities are relatively advantageous, even if they only work part-time. Indeed, a recent study suggests that family resources make it easier for women to remain at work, not to leave it (Damaske 2011). In contrast, working class women are more financially vulnerable in a neotraditional relationship given their relatively less lucrative and stable job prospects (both for themselves and for their potential spouses). This reality is underscored by the stated fallback relationship structure preferences of lower educated women in our study: the emphasis they place on self-reliance and breadwinning is consistent with a long tradition among working class women, especially women of color, of providing for themselves and their families through wage employment (Collins 1990; Deutsch 1999).

Our results regarding men's preferences under high levels of constraint (i.e., their “Fallback Plan” preferences) are also consistent with studies showing that, despite difficulties in doing so, working class men often aspire to fully provide for their families so their wives do not “have to” work (Deutsch 1999; Williams 2006; 2010). Because neotraditional arrangements are to some extent a modification of the “separate spheres” arrangements that have long characterized middle- and upper-middle class lifestyles, working class men may fall back on this arrangement because, for them, it signifies social status and class mobility. At the same time, as Gerson (2010a) notes, self-reliance for men means not having to be responsible for the care and feeding of a family. Thus, college-educated men's high level of identification with a self-reliant relationship structure may suggest that they are more likely to prioritize career success over family, an idea which is consistent with studies suggesting that middle- and upper-middle class families more often prioritize personal achievements over family relationships (Lareau 2003; Shows and Gerstel 2009). Importantly however, our study highlights a critical caveat to any interpretation of these patterns in fallback relationship structure preferences: they are expressed under conditions of highly gendered institutional constraint.

Our second main finding is that reducing these institutional constraints through policies that are supportive of dual-earner, dual-caregiver arrangements can have important implications for relationship structure preferences. However, the consequences of supportive policies are distinct for men and women. While women's preferences are responsive to supportive policies – leading them to be more likely to opt for an egalitarian relationship structure and less likely to opt for a neotraditional relationship structure – we do not find evidence that this is the case for men. On the one hand, the lack of findings for men underscores research suggesting that the cultural expectation for men to engage in breadwinning (while simultaneously avoiding substantial engagement in family care) is a particularly resilient dimension of masculinity (Thébaud 2010). In this interpretation, the desire among a significant subset of men to fulfill a neotraditional role is strong and largely impervious to policy context in part because they may feel they have less respect to gain (and more to lose) by taking advantage of work-family policies and increasing their contributions to household work. This idea is also consistent with findings suggesting that work-family policies that offer specific incentives for men to engage in caregiving, incentives which are not primed in our experiment, are most effective for changing men's behavior (see e.g., Hook 2006). On the other hand, the lack of findings for men underscores the extent to which cultural norms in the workplace are gendered (regardless of policy availability), such as the common perception that work-family policies only address “women's issues.” Thus, it is possible that a different sort of policy intervention, such as one that aims more explicitly to destabilize overwork norms, would affect men's work-family preferences more strongly than the policies examined here. Future research would be well served to investigate this set of issues.

Taken together, these results are consistent with theoretical arguments that gendered institutions have direct effects on individual preferences. In general, our findings suggest that highly constraining institutional arrangements may lead to more traditionally gendered work-family preferences, whereas institutional arrangements that alleviate those constraints may lead to less traditionally gendered (though not entirely de-gendered) work-family preferences. Therefore, as Stone (2007) suggests, a woman's decision to “opt-out” of a particular career track may more accurately reflect her strategy under high levels of institutional constraint, rather than her ideal work-family structure preference. The finding that the effects of supportive policies likely do not vary according to a woman's education level further underscores the idea that many non-professional women, who cannot afford to “opt-out,” also face suboptimal work-family arrangements and may make more gendered work-family decisions than they would ideally prefer. This finding also supports the theoretical argument of Gornick and Meyers (2009b) and others that work-family policies that support earner-caregiver arrangements should generally ameliorate gendered workplace constraints across the class structure.

To our knowledge, our study is the first test of the causal role of policy interventions on the relationship structure preferences of young men and women, which assists in moving forward the sociological theories of gender inequality at work and in the family. Yet, our study is not without limitations. First, although our research explores the preferences of young men and women, we are not able to observe respondents’ behavior. Stated preferences are certainly important, but we are not able to see whether respondents would act on their stated ideal. Second, the experimental condition with supportive work-family policies asks respondents to imagine that particular policies are in place. Most individuals in the United States, especially those in working class jobs, do not have access to policies that enable women and men to balance work and family life. However, if anything, we would expect the lack of real policies to bias our results in a conservative direction since there is no actual change to the respondents’ material circumstances. Third, the between-subjects design of our study does not enable us to examine how a given individual would respond to the supportive policy prime or how an individual respondent may shift his or her preferences depending on whether or not the egalitarian option is present. Future research could employ a within-subjects design to provide additional insights about how institutions shape young men's and women's preferences for their future work-family arrangements. Fourth, because college-educated young adults are somewhat more likely to be childless than those without a college education, it is possible that the lower educated respondents in our study are a more select sample on some dimensions. While not a threat to the validity of the findings presented above, future research could tease apart the extent to which this type of selection process may shape educational differences in relationship structure preferences.

Additionally, we did not oversample the LGBT community nor did we have information about respondents’ sexual orientation for our analysis. While this sample does not introduce bias into our results, it precludes us from systematically examining how institutional constraints may impact the relationship structure preferences of LGBT individuals in ways that are distinct from non-LGBT individuals. In a similar vein, we did not have enough respondents to investigate whether our results vary by race or ethnicity. We encourage future researchers to pursue these important lines of investigation.

Finally, our study focuses on the effects of work-family policies because these policies have constituted a focus of prior research pertaining to men's and women's decisions about work-family arrangements. However, there are other key aspects of institutions that could impact men's and women's work family preferences, especially the types of fallback relationship structures that individuals are likely to adopt. For instance, given that inequalities in income and employment opportunities likely underpin gender-differentiated fallback plans, policies aimed at reducing occupational sex segregation and/or ensuring equal pay and protection against workplace discrimination may also impact men's and women's fallback relationship structure preferences. Furthermore, it is possible that certain types of work-family policies may affect individuals’ preferences differently, and this may depend on whether they are implemented by governments or by employers. The effects of these and other aspects of institutional dynamics on work-family preferences should be evaluated in future research.

Though supportive work-family policies alone may not be sufficient to reshape gender inequality in the worlds of work and relationships (Blair-Loy 2003), our findings indicate that institutional environments and policies matter. Women's relationship structure preferences are particularly malleable to institutional designs that support egalitarian earner-caregiver relationships. Thus, major policy changes that enable workers to have more flexible schedules or that provide subsidized childcare have the potential to affect women's expectations, preferences, and aspirations regarding their level of engagement in the workforce (e.g., hours worked), and by extension, the form of such engagement (e.g., occupation) – both of which are key factors currently fueling the stubbornly gendered “supply” side of the inequality equation. Ultimately, by promoting preferences for egalitarian relationships, workplace institutions and policies that mitigate the challenges of balancing work and family life for women and men could help to jump-start the currently stalled progress toward gender equality.

Acknowledgments

We thank Youngjoo Cha, Shelley Correll, Patrick Ishizuka, Carly Knight, Lindsay Owens, Devah Pager, Liana Sayer, anonymous reviewers with Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences, and the anonymous reviewers and editors at American Sociological Review for helpful comments and suggestions. Data collection for this project was supported by Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences, NSF Grant 0818839, Jeremy Freese and James Druckman, Principal Investigators. Generous support for this research was provided by the Center for the Study of Social Organization at Princeton University and NICHD (5 R24 HD042849).

Appendix A. Experimental Prompts

In this Appendix, we present the prompts for our three experimental conditions. Any text not to be presented to respondents is placed in brackets, such as these [ ].

[Randomly assign respondents to one of the following three experimental conditions. The order of response categories is also randomized.]

[Condition #1: No Egalitarian Option, No Mention of Supportive Policies]

We are interested in learning about the ways that people hope to structure their future work and family lives.

Which of the following options best describes how you would ideally structure your future work and family life?

I would like to maintain my personal independence and focus on my career, even if that means forgoing marriage or a life-long partner.

I would like to have a life-long marriage or committed relationship in which I would be primarily responsible for financially supporting the family, whereas my spouse or partner would be primarily responsible for managing the household (which may include housework and/or childcare).

I would like to have a life-long marriage or committed relationship in which I would be primarily responsible for managing the household (which may include housework and/or childcare), whereas my spouse or partner would be primarily responsible for financially supporting the family.

[Condition #2: With Egalitarian Option; No Mention of Supportive Policies]

We are interested in learning about the ways that people hope to structure their future work and family lives.

Which of the following options best describes how you would ideally structure your future work and family life?

I would like to maintain my personal independence and focus on my career, even if that means forgoing marriage or a life-long partner.

I would like to have a life-long marriage or committed relationship in which I would be primarily responsible for financially supporting the family, whereas my spouse or partner would be primarily responsible for managing the household (which may include housework and/or childcare).

I would like to have a life-long marriage or committed relationship in which I would be primarily responsible for managing the household (which may include housework and/or childcare), whereas my spouse or partner would be primarily responsible for financially supporting the family.

I would like to have a life-long marriage or committed relationship where financially supporting the family and managing the household (which may include housework and/or childcare) are equally shared between my spouse or partner and I.

[Condition #3: With Egalitarian Option; With Supportive Policies]

We are interested in learning about the ways that people hope to structure their future work and family lives.

Raising children, caring for ill family members, and/or taking care of household responsibilities involves a considerable amount of time and energy. In the United States, the cost of paying others to help with these responsibilities (such as childcare) is also high. However, if policies were in place that guaranteed all employees access to subsidized childcare, paid parental and family medical leave, and flexible scheduling (such as the ability to work from home one day per week), which of the following options best describes how you would ideally structure your future work and family life?

I would like to maintain my personal independence and focus on my career, even if that means forgoing marriage or a life-long partner.

I would like to have a life-long marriage or committed relationship in which I would be primarily responsible for financially supporting the family, whereas my spouse or partner would be primarily responsible for managing the household (which may include housework and/or childcare).

I would like to have a life-long marriage or committed relationship in which I would be primarily responsible for managing the household (which may include housework and/or childcare), whereas my spouse or partner would be primarily responsible for financially supporting the family.

I would like to have a life-long marriage or committed relationship where financially supporting the family and managing the household (which may include housework and/or childcare) are equally shared between my spouse or partner and I.

Appendix B. Multinomial Logistic Regression Analyses

We estimated multinomial logistic regression models in addition to the binary logistic regression models presented in the body of the article. These models enable us to jointly examine the full set of respondents’ relationship structure preferences. For these models, the outcome variable consists of the four types of relationship structures that respondents could select – egalitarian, neotraditional, counter-normative, and self-reliant – and the independent variable is whether the respondent was in the “Supportive Policies” condition versus the “Egalitarian Option Present” condition. Respondents in the “Fallback Plan” condition are not included in these analyses because there were a different number of response categories in that condition.

The results are presented in Table B1, below. Model B1 examines the consequences of the supportive policy prime for women's selection of their relationship structure preferences. The omitted outcome category is a neotraditional relationship. More important than the individual supportive policy coefficients is whether there is an overall effect of the supportive policy prime on women's relationship structure preferences. An adjusted Wald test indicates that the supportive work-family policy prime affected women's overall relationship structure preferences in a statistically significant way (F(3, 88) = 131.34, p < .001). Model B2 includes an interaction between being in the “Supportive Policies” condition and women's education level. We did not find evidence that these effects differ across women's education levels. An adjusted Wald test indicates that there is no meaningful moderating effect of women's education on the consequences of the supportive policy prime (F(3, 88) = .57, p = .64).