Abstract

Aims

A discussion of conceptual frameworks applicable to the study of isolation precautions effectiveness according to Fawcett and DeSanto-Madeya’s (2013) evaluation technique and their relative merits and drawbacks for this purpose

Background

Isolation precautions are recommended to control infectious diseases with high morbidity and mortality, but effectiveness is not established due to numerous methodological challenges. These challenges, such as identifying empirical indicators and refining operational definitions, could be alleviated though use of an appropriate conceptual framework.

Design

Discussion paper

Data Sources

In mid-April 2014, the primary author searched five electronic, scientific literature databases for conceptual frameworks applicable to study isolation precautions, without limiting searches by publication date.

Implications for Nursing

By reviewing promising conceptual frameworks to support isolation precautions effectiveness research, this paper exemplifies the process to choose an appropriate conceptual framework for empirical research. Hence, researchers may build on these analyses to improve study design of empirical research in multiple disciplines, which may lead to improved research and practice.

Conclusion

Three frameworks were reviewed: the epidemiologic triad of disease, Donabedian’s healthcare quality framework and the Quality Health Outcomes model. Each has been used in nursing research to evaluate health outcomes and contains concepts relevant to nursing domains. Which framework can be most useful likely depends on whether the study question necessitates testing multiple interventions, concerns pathogen-specific characteristics and yields cross-sectional or longitudinal data. The Quality Health Outcomes model may be slightly preferred as it assumes reciprocal relationships, multi-level analysis and is sensitive to cultural inputs.

Keywords: Theoretical models, conceptual analysis, nursing, patient isolation, cross-contamination, healthcare-associated infection, barrier precautions, contact precautions, infection prevention, infection control

INTRODUCTION

Isolating those with communicable pathogen(s) has been a key means to control disease since the black plague in the 14th century (Landelle et al. 2013). Today, isolation precautions are still a preferred method in many healthcare systems to control infectious diseases with high morbidity and mortality, such as Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Smith et al. 2008, Siegel et al. 2007). However, high resource requirements (Kirkland 2009), associated adverse events (Morgan et al. 2009) and evidence-based medicine prioritization (Swanson et al. 2010) have sparked debate as to whether existing data regarding isolation precautions are adequate to guide effective practice (Gasink & Brennan 2009). This debate intensified following transmission of Ebola virus to healthcare workers in the U.S. despite use of isolation precautions (Santora 2014). It is important to generate new, consistent data regarding optimal infection control techniques to improve clinical practice (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013).

However, it remains challenging to demonstrate isolation precautions are effective. Recent studies of isolation precautions effectiveness took place in many different countries including France (Gbaguidi-Haore et al. 2008), Great Britain (Cepeda et al. 2005), Hong Kong (Cheng et al. 2010), Israel (Cohen et al. 2011), Taiwan (Lin et al. 2011) and the United States (Bearman et al. 2010, Bearman et al. 2007). Similar studies were rarely repeated in the same country. As wide variation exists in clinical practice guidelines regarding isolation precautions, even among those from English-speaking countries (Aboelela et al. 2006), variation in the healthcare systems and isolation precautions processes threatens external validity of study results (Zastrow 2011). Therefore, it is difficult to combine and draw conclusions from this international body of literature.

Although substantial methodological barriers exist in this area, improvement is possible. Challenges that are difficult or impossible to address include establishing temporality between exposure and infection given new resistance and asymptomatic colonization periods (Gasink & Brennan 2009) and blinding intervention and outcomes (Aboelela et al. 2006). As isolation precautions are not recommended in all countries, randomized controlled trials of isolation precautions are uncommon. Because the most relevant study designs (quasi-experimental and observational studies) limit the researcher’s ability to control for confounders (Siegel et al. 2007), addressing confounders and accounting for bias is critical. Future studies may also improve on existing literature assessing compliance with all aspects of the intervention (Landelle et al. 2013) as well as fully describing the environment and outcome assessment methods . Careful study design to evaluate isolation precautions is essential, not only to produce rigorous results, but also to fully consider all the risks and benefits to patients, providers, facilities, allowing interpretation of findings by an international audience.

Background

Using a conceptual framework can be an effective tool to guide research of complex problems by helping to define concepts relevant to the phenomenon of interest and outline the relationships between these concepts (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya 2013). Conceptual frameworks also can help to refine operational definitions and identify empirical indicators for these concepts. They aid derivation of theories, research questions and corresponding logical hypotheses to be tested in empirical research (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya 2013). Given the difficulties of studying isolation precautions, appropriate conceptual frameworks may advance theory generation and improve evaluation through empirical research.

When designing a study, it is essential to ensure that the chosen conceptual framework and theory under investigation are logically aligned (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya 2013). While infection control and prevention is inherently a multidisciplinary effort, nurses are a critical component given their frequent, direct patient contact, education and research roles. Therefore, effectiveness research should consider nursing roles, perspectives and theory to maximize applicability of research findings. Models from other disciplines which appear potentially applicable to nursing issues ‘should be critically analyzed and evaluated before it is introduced into nursing curricula, empirically tested or applied in nursing practice’ (Sullivan 1989).

The objective of this paper is to support study design by identifying, analyzing and evaluating conceptual frameworks to study the effectiveness of isolation precautions. This paper discusses the relative merits and drawbacks of each to frame empirical research on this topic and compares which conceptual frameworks are best-suited for various study designs used to evaluate isolation precautions effectiveness. Further, it outlines a critical thinking process regarding how to choose a conceptual framework, which may of useful beyond infection control research.

Data Sources

In mid-April 2014, C.C.C. performed a systematic search of electronic, scientific literature databases for peer-reviewed publications using or describing a conceptual framework applicable to examine the effectiveness of isolation precautions. Databases included PubMed, Ovid Medline, EBSCO Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Keyword searches were supplemented by Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms in the search criteria, where applicable and related to the following concepts: Patient isolation (i.e., ‘barrier precautions’, ‘contact isolation’, ‘contact precautions’, ‘isolation precautions’, ‘quarantine’) and conceptual frameworks (i.e., ‘theoretical model’, ‘conceptual model’, ‘organizing framework’, ‘theoretical framework’), in singular and plural forms. Search parameters included publication in English. Searches were not limited by publication date.

C.C.C. examined titles and abstracts of papers returned through database searches for potentially applicable conceptual frameworks. Additional publications were sourced through reference lists of papers returned in the database search. Conceptual frameworks previously known to the authors were also considered. C.C.C. then identified original literature that proposed these frameworks of interest as well as publications by the original author(s) that further elaborate on these frameworks.

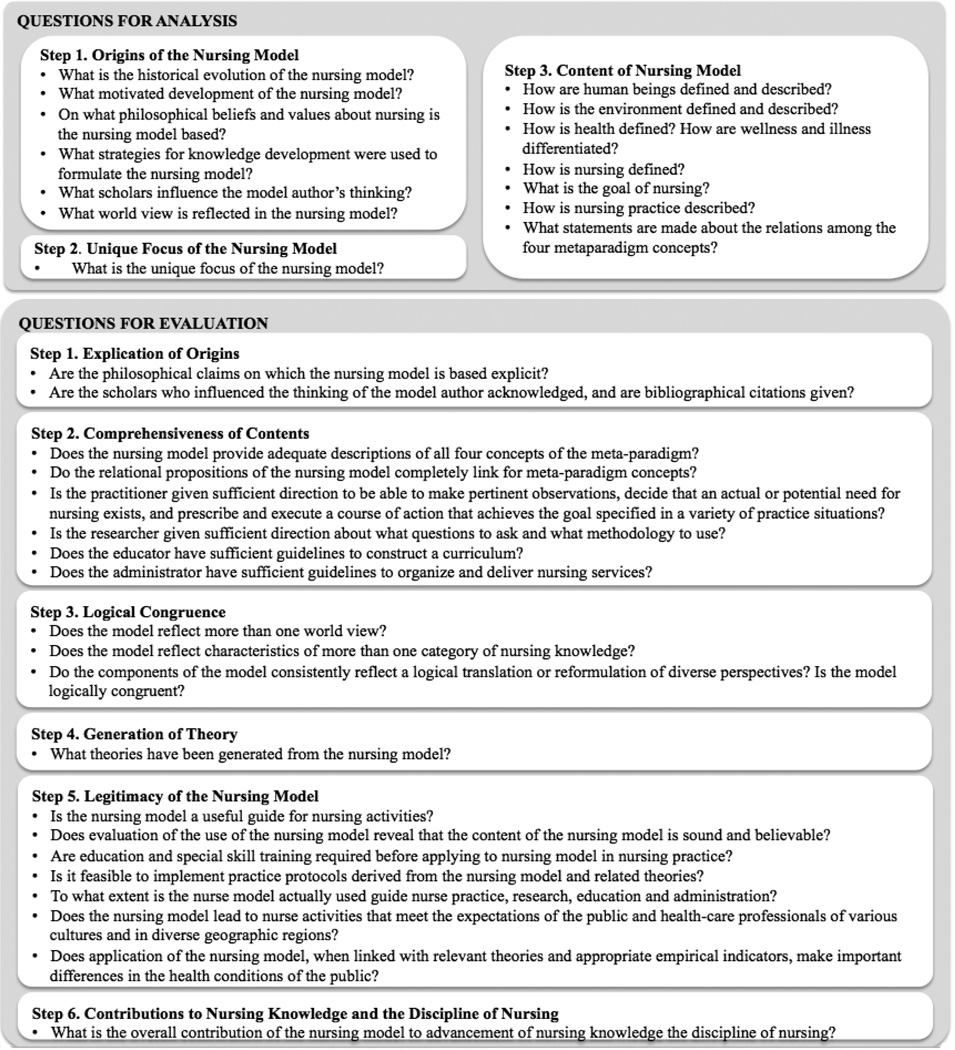

Frameworks selected for analysis were included based on 1) applicability to the study of isolation precautions effectiveness and 2) the number of times the publications that originally proposed this conceptual framework has been cited on PubMed. Applicability and usefulness of the identified conceptual frameworks were evaluated following the analysis technique outlined by Fawcett and DeSanto-Madeya (Figure 1) (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya 2013).

Figure 1.

Framework for Analysis and Evaluation of Nursing Models (Adapted from Fawcett and Desanto-Madeya, 2013).

DISCUSSION

Searches of electronic databases yielded 128 publications, 25 of which were duplicates. Six conceptual frameworks were identified relevant to the study of isolation precautions (Table 1). Among the six frameworks, the epidemiologic triad of disease (though not always titled as such, as discussed below) was most frequently cited by other publications in PubMed (247 times), followed by Donabedian’s healthcare quality framework (67 times) and Quality Health Outcomes framework (21 times). The other two frameworks were each cited less than four times. We described the three more frequently cited frameworks and evaluated their usefulness to study isolation precautions effectiveness (Table 2).

Table 1.

Identified conceptual frameworks applicable to the study of isolation precautions, presented in chronological order of publication

| Framework Name | Source | Description | Constructs Included | PubMed Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiologic triad of disease |

Clark 1954 | Describes the three categories of factors and their interrelationships that influence epidemics |

|

247** |

| Donabedian’s healthcare quality framework |

Donabedian 1966 | Identifies three factors by which to assess the quality of health care delivery and the linear flow of influence between them |

67 | |

| Conceptual model of an infection surveillance and control program (ISCP) |

Haley et al. 1981 | Relates nosocomial infection (a patient characteristic) to all activities performed by an ISCP for the purpose of evaluating those activities’ impact on the patient characteristics |

1 | |

| Quality health outcomes framework |

Mitchell et al. 1998 | Building on Donabedian, introduces dynamic interrelationships between concepts and an indirect path between intervention and outcomes influenced by the system and client(s) |

|

21*** |

| Predisposing, reinforcing and enabling factors in education and health diagnosis and evaluation model (PRECEDE) |

Mody et al. 2011 | Describes the process to implement interventions in high risk groups by health care workers, model proposed specifically in relation to prevention of HAI |

|

3 |

| HAI prevention system framework |

Kahn et al. 2014 | Specifies system-based components for HAI prevention and mitigation |

0 |

Represents concept(s) in which isolation precautions are incorporated

Includes papers containing Agent-Host-Environment as in Clark (1954), though not cited and/or titled differently

Incorporates Mitchell and Lang (2004) and cited articles

HAI = Healthcare associated infections; ISCP = Infection surveillance and control program.

Table 2.

Evaluation of three most-cited frameworks applicable to the study of isolation precaution effectiveness

| Evaluation Criteria | Clark (1954) | Donabedian (1966) | Mitchell (1998) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explication of Origins |

Yes. Desire for increased health promotion and disease prevention to meet patient demands in medicine and dentistry stated. Works of numerous named and ‘unnamed’ authors credited for ‘epidemiologic viewpoint’ as a lens for framework development (Leavell & Clark 1958) |

Yes. Personal experience with individual level physician-client relationship implicated as well as publications for framework development and explication, such as Sheps (1955), among others |

Yes. Influences of the goals of Outcomes Measures and Care Delivery Systems invitational conference and work of Donabedian (1966), Holzemer & Reilly (1995), Wilson and Cleary (1995) acknowledged |

|

Comprehensiveness of Content |

Incomplete. Nursing inputs/interventions not included in model |

Complete. All nursing domains and relational propositions addressed, though not identified as such |

Complete. All nursing domains and relational propositions addressed |

| Logical Congruence |

Yes. Consistent with Reaction World View, person-environment and intervention categories of knowledge |

Yes. Consistent with Reaction World View, outcomes and interventions category of knowledge |

Yes. Consistent with Reciprocal World View, outcomes category of knowledge |

| Generation of Theory |

Yes. Few examples in the literature that use the model to generate nursing theory |

Yes. Numerous nursing publications use this framework to generate testable hypotheses |

Yes. Multiple nursing publications use this framework to generate testable hypotheses |

| Legitimacy |

Mixed. Few examples found of successful hypothesis testing in nursing, inspired creation of adapted nursing model (Reifsnider 1995) |

Mixed. Model has been used to guide nursing research and practice successfully, but has also inspired creation of adapted nursing models (Mitchell et al. 1998, Shield et al. 2014) |

Yes. Successful hypothesis testing published without limitations due to the model |

| Social Utility |

Moderate. No education or skills required. Ability to implement protocols derived from model based on expert opinion (Zastrow 2011, Massanari 1989) |

High. No education or skills required. Ability to implement protocols |

High. No education or skills required. Ability to implement protocols |

| Social Congruence |

Unknown. Usefulness across cultures and geographies not published in nursing |

High. Cross-cultural/diverse geographic application published in nursing research (Chen et al. 2007, Closs & Tierney 1993) |

High. Applied to nursing care among facilities in diverse geographic locations and with diverse patient demographics (Brooks-Carthon et al. 2011, Shang et al. 2014) |

| Social Significance |

High. Versatility of model yields high applicability in diverse subjects and fields |

High. Model is well-integrated into nursing research with high impact on practice |

High. Model directed at nursing outcomes with significant influence |

|

Contributions to Nursing Knowledge and nursing Discipline |

High. Effective organizing framework though few papers identified using this model to generate theory |

High. Breadth of model concepts yield broad applicability in nursing |

High. Model has effectively guided nursing activities such as several report card initiatives |

Epidemiologic Triad of Disease

Description

The epidemiologic triad of disease is also referred to in the literature as the ‘epidemiologic triad of agent/host/environment’ (Bernardo et al. 2002), ‘host-agent-environment complex’ (Smith 1986), ‘agent-host-environment model’ (Zastrow 2011), ‘epidemiologic triangle’ (Huerta & Leventhal 2002) and the ‘traditional public health triangle’ (Wilde 1997). As detailed in a textbook focused on ‘health promotion and disease prevention’ in medicine and dentistry (Leavell & Clark 1958), the motivation for development of this model was to frame infection prevention strategies (Clark 1954) and assemble facts in a body of knowledge regarding the natural history of disease (Leavell & Clark 1958). Although originally developed to describe infectious disease, the framework was also used in studies related to non-infectious disease, such as lead poisoning (Clark 1954) or nutrient deficiency (Leavell & Clark 1958).

The epidemiologic triad of disease identifies three components necessary to initiate and propagate illness (Leavell & Clark 1958), including a host (i.e., susceptible individual), an agent (i.e., a pathogen) and environment compatible with transmission of a disease-causing entity (Figure 2). As such, the environment, described as ‘all things except man himself’ (Leavell & Clark 1958), also includes biologic and socioeconomic factors in addition to the physical environment that ‘may be preparing the way long before pathogenesis is initiated’ (Clark 1954). In the original framework, Clark (1954) targeted interventions to intercept the causes contributing to disease process and proposed five ‘levels of application of preventive measures’ (Clark 1954). Variations of this model including a central ‘vector’ concept linking the other three (Huerta & Leventhal 2002) and presenting the framework as a tripod (or triangle) of the three concepts (Scholthof 2007) rather than a balance between agent and host with environment as the fulcrum (Leavell & Clark 1958).

Figure 2.

The Epidemiologic Triad of Disease (Clark 1954)

Analysis

Because this framework is originally from the medical discipline, it purports no philosophical beliefs, values, goals or descriptions with regard to nursing practice. The authors’ views regarding the general purpose of nursing interventions are not stated in descriptions of the framework, neither are relationships to the domains of nursing. The general method of knowledge development using this framework is deductive as Leavell and Clark (1958) believe that knowledge of the natural history of disease can ‘fill in the gaps’ regarding what is known of the agent, host and environment in a particular situation (Leavell & Clark 1958), that is, using theory to deduce what empirical observations may occur (Reed 2012).

Regarding nursing metaparadigm domains of nursing, environment, health and person(s)/client/human beings (Peterson & Bredow 2013), the model could be interpreted as addressing client and the environment. Human beings are described as both a reservoir of disease and also a compilation of ‘habits and customs’ and that influence the interaction between agents of disease and the individual (Clark 1954). As mentioned above, environment is described as multi-factorial influences on the ‘life and development of an organism’, including biologic and socioeconomic as well as physical entities (Clark 1954). Because the authors wanted to outline a health promotion philosophy when developing this framework, health is implied in this model through the host’s level of susceptibility. Nursing is not included, which might be interpreted as a significant weakness of this model for framing interventional research.

Evaluation

The origins of the model in medical epidemiology are not an inherent weakness for nursing or multidisciplinary studies as many conceptual frameworks of non-nursing origin have been successful to generate and test nursing theory (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya 2013). This framework has been used in nursing research (Bernhardt & Langley 1999, Bernardo et al. 2002), including for infection control (Massanari 1989, Wilde 1997). In applications to the study of isolation precautions, this framework emphasizes a means to change the environmental component, breaking the links to both presence of an agent and contact with a susceptible host. The model was also specifically identified as a useful tool to study contact precautions (Zastrow 2011). Indeed, simplicity of the framework and breadth of concepts are strengths that enhance the model’s applicability to diverse disciplines and topics.

However, the model is limited in comprehensiveness of content regarding nursing inputs and perspectives. The lack of a nursing or intervention-specific concept in the framework may not be a concern for describing the natural history of disease or even testing a single intervention’s effects. However, to compare multiple interventions, the framework may require adaptation to capture effects of the interventions, especially if they affect the same concept (e.g., host) in different ways (e.g., education regarding isolation precautions procedures versus vaccination). Despite these weaknesses, researchers have used this framework from nursing perspectives. For example, in the study of occupational nursing, Smith (1986) used the framework from a different worldview by assuming mutable agent, host and environment as well as dynamic relationships between these concepts (Smith 1986). Similarly, Reifsnider (1995) adapted the framework to show multiple inputs to each concept as well as reciprocal relationships between environment and host (Reifsnider 1995). Given that nurse scientists saw fit to adapt the model for use, the original framework may fail to capture the complexities of nursing interventions required to study isolation precautions.

Donabedian’s Healthcare Quality Framework

Description

In 1966, Avedis Donabedian proposed that the quality of medical care can be evaluated through consideration of structure, process and outcomes of that care (Figure 3) (Donabedian 1966). Structure, the setting where medical care takes place and ‘instrumentalities’ that produce care processes, includes the ‘adequacy of facilities and equipment’ needed to provide care, provider qualifications, ‘fiscal organization’ as well as ‘administrative and related processes that support and direct the provision of care (Donabedian 1966). Process, ‘medical care’ (Donabedian 1966), includes not only technical skills, but also whether medical evidence has been applied in decision-making, the ‘appropriateness, completeness and redundancy’ of information obtained regarding the client and whether the client values the care provided (Donabedian 1966). Outcomes of medical care, the ‘recovery, restoration of function and of survival’ of a client (Donabedian 1966), is described by Donabedian as product of structures and processes.

Figure 3.

Donabedian’s Quality Health Outcomes Framework, Note that the following is sometimes depicted with a separate ‘client characteristics’ concept leading to/influencing ‘processes’ (Donabedian 1966)

This framework applies to the study of isolation precautions as isolation precautions are represented in structure and process concepts. For example, structure encompasses the availability of a private room and processes include the use of gowns and gloves for contact with the patient and the patient’s environment. Outcomes related to isolation may be infection or colonization with a specific pathogen, among others.

Analysis

With its medical field origin, Donabedian specifically focused on quality evaluation of physician-patient interaction, as this was ‘familiar territory of care’(Donabedian 1966). Similarly to the epidemiologic disease triad, Donabedian’s model is not built on any philosophical beliefs and values specific to nursing nor does it inherently include any strategies for nursing knowledge development. It therefore does not have a unique focus in nursing. Donabedian’s method of knowledge development using this model appears to be abductive system of reasoning, as it represents ‘a conceptual leap form experience, beliefs and a pre-knowledge of patterns to arrive at an educated guess or theory about a phenomenon’ (Reed 2012).

When Donabedian described this framework, he did not address domains of the nursing metaparadigm; however, when applying this framework to evaluate nursing or interdisciplinary care, the framework could incorporate all domains. Human beings are included both in structures (e.g., health care provider staffing) and in the influence of client characteristics on processes. Structure also describes the environment where healthcare is delivered. Health is measured by outcomes. Donabedian’s model previously received criticism that structure and process concepts are ill-defined for nursing which may, at times, fit into both (Closs & Tierney 1993). However, for the sake of evaluating isolation precautions, both structure and process factors would certainly need to be considered in a well-designed study. Therefore nursing activities and attributes need not fit into a single concept in this model.

Evaluation

The Donabedian model is so well established in healthcare quality research that, despite its origins in medicine, one could argue that it is very well aligned and logically congruent with most nursing theory and knowledge developed in its wake. In nursing, it has been used to evaluate quality of hospice care (Richie 1987), elderly discharge planning (Closs & Tierney 1993), nurse practitioner services (Gardner et al. 2014) and obstetrical/labor and delivery patient perceptions (Hosek et al. 2014), among others. Research studies that use this framework demonstrate its social congruence in multiple geographic location and cultures (Chen et al. 2007, Closs & Tierney 1993), indicating the international relevance of its content. Considering that this framework has successfully guided nursing theory development and testing in this way, its empirically adequate use is a distinct strength (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya 2013).

While the content of the framework is purposefully broad to be widely applicable, it may not be ideal to study isolation precautions as it lacks a clear component or role regarding the characteristics of pathogens (e.g., the ‘agent’ concept in the epidemiologic triad of disease). This reflects that the unique focus of the model is not infection control. To use Donabedian’s model in infection control studies, the structure component may best incorporate the concept of a dangerous agent present in the environment and perhaps the pathogen’s virulence and pathogenicity.

Another limitation of this model is that ‘the relation between structure and process is poorly understood’ (Donabedian 1978). This lack of clear relational propositions between concepts may be a significant drawback for guiding studies on this topic. As such, nursing researchers have defined the relational propositions interactions more explicitly (Richie 1987) and also proposed new, adapted models (Chen et al. 2007, Shield et al. 2014, Mitchell et al. 1998).

Furthermore, the relationship between outcomes and other concepts in the Donabedian model also may not be ideal to study isolation precautions. For example, during a suspected influenza outbreak, confirmation of each additional case in a facility (outcomes) may change the process for isolation precautions for the next individual with a suspected case of influenza. The propensity to isolate and hence structures and processes of practice, will have changed as a result of what the Donabedian model identifies as outcomes. It is not clear how this reciprocal influence might be reflected in the Donabedian model.

Quality Health Outcomes Model

Description

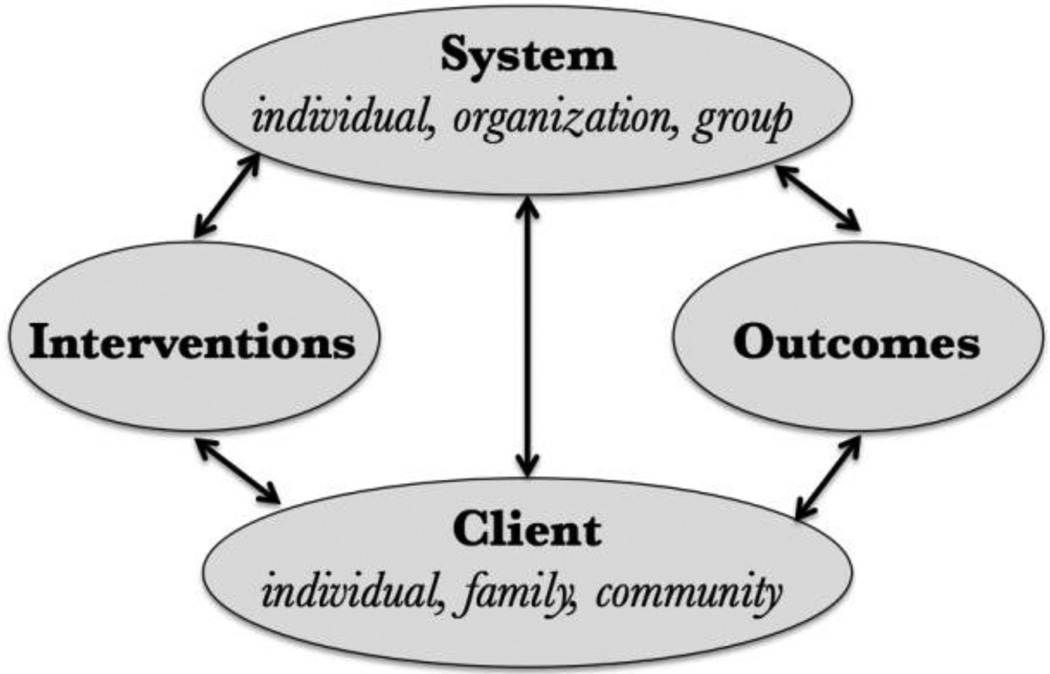

Building on Donabedian’s linear framework of healthcare quality improvement, the Quality Health Outcomes Model (Mitchell et al. 1998) includes four components: system, client, interventions and outcomes (Figure 4). System characteristics incorporate structure and process elements of the Donabedian model. Similar to processes in the Donabedian model, the interventions component represents clinical processes and related activities by which they are performed. Unlike Donabedian, Mitchell and colleagues specify client characteristics, which are indicators of health status, demographics and disease risk factors of individual patients, families and communities. Outcomes are health indicators such as morbidity, mortality and other variables dependent on the previously listed components (Mitchell et al. 1998). Relational propositions between concepts in the Quality Health Outcomes framework are dynamic and the relationship between interventions and outcomes is indirect and mediated by system and client components (Mitchell et al. 1998).

Figure 4.

The Quality Health Outcomes Framework (Mitchell et al. 1998)

This framework applies to the study of isolation precautions effectiveness as it was developed to facilitate testing complex relationships between concepts with attention to nursing contributions (Mitchell et al. 1998). Interventions represent the processes of isolation precautions, while the system characteristics (e.g., nursing staffing ratios) and client characteristics (e.g., isolation adherence related to mental status) mediate the intervention’s effects on the outcome (e.g., facility infection rate). The decision to isolate includes client and system characteristics, balancing the negative consequences of isolation on the individual with the benefits of reduced infection risk to a larger group of individuals. In this way, the content of this nursing conceptual model is appropriate to study isolation precautions.

Analysis

The origin of this model was the Outcomes Measures and Care Delivery Systems Invitational Conference (Mitchell & Lang 2004), which targeted defining categories of outcome indicators that can affect health policy. As such, the unique focus of this model is outcomes, especially nursing outcome research and management. The authors believe that a model with multiple feedback loops between the components and outcomes would be more sensitive to nursing inputs than the Donabedian model (Mitchell et al. 1998). The authors also incorporated multi-level analysis, as proposed by Holzemer and Reilly (1995) and clinical and functional outcomes introduced by Wilson and Clearly (1995). Their motivation was to establish a model broad enough to guide database development, suggest key clinical intervention variables, provide a framework for research and influence health policy (Mitchell et al. 1998).

The authors appear to have used abductive reasoning (Reed 2012, Sullivan 1989) to develop this conceptual guide as it was derived from ‘expert panel members’ ongoing research, expert opinion and literatures of nursing and health services’ (Mitchell & Lang 2004). However, the authors specifically support use of this model for inductive knowledge development (‘the process of subjecting the theoretical ideas to empirical test’ (Reed 2012)). Influences of specific philosophies are not stated. However, the authors’ description of the model notes that the impacts of nursing inputs are mediated by individual client characteristics and contextual factors of the system where care is provided. This appears to take a postmodern approach (i.e., outcomes are dependent on context) (Reed 2012). Hence, both outcomes and mediators require sensitive measures to capture nursing value.

Mitchell and colleagues specifically incorporated all four nursing metaparadigm domains in this model (Mitchell & Lang 2004). The desire to incorporate broader outcomes than negative events (i.e., the 5-Ds: death, disease, disability, discomfort, dissatisfaction) (Mitchell & Lang 2004) reflects the domain of health. It may also be argued that environment is present in the system characteristics concept, intervention contains nursing and both client characteristics and outcomes can differentiate between illness and non-illness states. The person(s) domain might be interpreted as aspects of healthcare workers in system characteristics as well as influencing client characteristics.

Evaluation

Regarding the study of isolation precautions, the Quality Health Outcomes model is similar to Donabedian’s framework in that it lacks an ‘agent’ concept as described by Leavell and Clark (1958). In this model, the system characteristics concept best incorporates presence of a disease agent. Another potential flaw in this model is that direct relationships between intervention and outcomes are not possible. As stated above, this framework purports that the relationship between intervention and outcomes is always mediated by system and client characteristics. Therefore, in a hypothetical study population that is homogenous with regard to system and client characteristics, the authors question whether relational propositions described by the model are meaningful. However, though individual studies regarding isolation precautions are often performed in a single unit or facility, it is unlikely that system and client characteristics can be sufficiently homogenized based on existing studies. In this way, the model appears to be appropriate for empirical research regarding isolation precautions with these mediators influencing the intervention-outcome relationship.

The strengths of this model are its intentionally broad concepts and numerous published examples of use in nursing research. This model has influenced theory relating health outcomes to nurse staffing (Shang et al. 2014), patient experience (Lundgren & Wahlberg 1999), system characterization (Dubois et al. 2012) and recognition of nursing excellence (Lake et al. 2012), among others. Contributions to the nursing discipline also include guiding several nursing report card initiatives (Mitchell & Lang 2004). The studies using this model indicate that the model has international relevance as they take place in multiple countries and represent different cultures (Brooks-Carthon et al. 2011, Shang et al. 2014). In summary, this model has been sufficiently validated through contributions to the nursing discipline.

Other key strengths of the Quality Health Outcomes model are the incorporation of system and client characteristics concepts and the assumption of multi-level analysis. First, the mediating concepts of system and client and indirect relationship between interventions and outcomes compels researchers to account for differences between populations and settings where studies of isolation precautions effectiveness are performed, for example, different resources available in another healthcare system and cultural influences of that country on psychological adverse events associated with isolation precautions. This is particularly important for repeating studies in diverse settings, interpreting findings from studies performed in other countries and synthesizing data collected in diverse geographic regions, which is particularly relevant to the highly international body of literature regarding isolation precautions effectiveness. Second, incorporation of Holzemer’s multi-level analysis (Mitchell & Lang 2004) allows the model to address risk and benefits at both the individual and group levels. Including variables at multiple levels is integral to the study of isolation precautions as the isolation precaution benefits (e.g. reduced infection risk) are realized by a group of patients at the facility or unit level and the harms (e.g., depression) are specific to the individual in isolation. Therefore, the Quality Health Outcomes framework allows detailed reflection in study design of isolation precautions and considerations for cross-cultural sensitivities.

Implications for Nursing

Our review of scientific literature revealed that comparative evaluations of conceptual frameworks for their applicability to a given topic are rarely published, although researchers often evaluate and compare conceptual frameworks when designing research studies. This paper outlines thought processes to compare usefulness of conceptual frameworks. Therefore, this paper may be of use to researchers designing new studies and administrators and clinicians evaluating results of these studies in multiple fields beyond infection control practices.

Analysis and comparison of frameworks, as described in this paper, may be helpful to assist multidisciplinary projects and/or international collaborations in infection control as well as other fields. Multidisciplinary research necessitates conceptual translation, establishing uniform language and ‘common or at least correlated approach to individual questions’ (Kessel et al. 2008). Collaboration across cultures and healthcare systems also requires mutual conceptual understanding for success. For example, combating the on-going Ebola epidemic requires a coordinated, global effort to maximize effectiveness of isolation precautions and other infection control practices with attention to local health beliefs, resources and disease strains. Evaluating and using a conceptual framework may be ideal to level expectations among stakeholders before beginning a study or intervention.

Regarding isolation precautions, use of a conceptual framework may improve empirical research design, leading to improved clinical practice. In previous studies, it is unclear whether authors did not address confounders or biases because it was impractical or whether these issues were not considered. However, application of one of these conceptual frameworks may have prompted authors to compare ‘client characteristics’ in the Quality Health Outcomes Framework (or ‘host’ in the epidemiologic triad) of the pre and post-intervention groups. For example, some previous studies did not report the proportion of the respective sample with immunocompromised status or indwelling devices (Bearman et al. 2010, Bearman et al. 2007, Cheng et al. 2010, Cohen et al. 2011), which are known risk factors for infection (Siegel et al. 2006). Further, operationalizing the process concept in Donabedian’s framework (or ‘intervention’ in Mitchell’s) may have prompted Gbaguidi-Haore et al. (2008) to report compliance, Cohen et al. (2011) to track compliance consistently across different phases of the study or Cepeda et al. (2005) and Cheng et al (2010) to record compliance for all components of the intervention. Detailing structure and processes (or ‘environment’ or ‘system characteristics’) would be helpful to understand equipment access, regular provider training and case communication, especially for studies conducted in different healthcare systems. Understanding the representativeness of the sample, level of intervention compliance and system characteristics would help clinicians to determine whether to apply these interventions in clinical practice.

All three conceptual frameworks reviewed in this paper could be used to guide study of isolation precautions, though none are ideal. While the epidemiologic triad of disease does not contain a clear concept for interventions but is sensitive to pathogenicity and virulence of specific infectious agents, the reverse is true of Donabedian’s framework and the Quality Health Outcomes model. As isolation precautions are initiated in response to infection, lack of a pathway by which outcomes influence structure and process may be problematic. In this way, the Donabedian model would not help to address temporality between exposure and outcome, which is a significant challenge in infection control intervention studies (Gasink & Brennan 2009). In contrast, Mitchell et al.’s (1998) recognition of need for multi-level analyses may help researchers to distinguish between individual-level outcomes that trigger isolation precautions and facility-level variables that follow isolation precautions use. Furthermore, The Quality Health Outcomes model also has a strength that differentiates it from Donabedian’s framework and the epidemiologic triad of disease: incorporation of system and client characteristics concepts. Hence, the Quality Health Outcomes model may be slightly preferred for nursing studies regarding isolation precautions, depending on outcome(s) of interest and study design.

The strengths and weakness of the three conceptual frameworks indicate they may be better-suited to specific study designs used to evaluate isolation precautions. The epidemiologic triad of disease may be most useful for observational studies, especially cohort studies (i.e., exposure has already occurred (LoBiondo-Wood & Haber 2006)) where there is no need to observe the effects of an intervention, but perhaps a need to capture biological characteristics of the agent (e.g., presence of specific strains or pathogenicity). An example of such a study is Tschudin-Sutter et al., (2010) which assessed risk of developing extended-spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae among roommates of infected individuals (i.e., exposure prior to being moved into isolation precautions) (Tschudin-Sutter et al. 2012). Donabedian and Mitchell et al.’s frameworks are more efficient for interventional studies. The dynamic nature of the Quality Health Outcome framework would be well-suited to both mathematical model-based studies where all factors related to isolation precautions are simultaneously influencing others (e.g., cross-sectional analysis) (Chow et al. 2011), as well as capturing dynamic responses over time. While neither the Donabedian or Mitchell model has a direct path between outcomes and structure/process or intervention, respectively, Mitchell’s framework contains an indirect pathway by which outcomes can influence interventions. Therefore, longitudinal studies may not benefit as much from the Donabedian model as from Mitchell’s framework. However, pretest-posttest studies, as are often used to study isolation precautions (Aboelela et al. 2006), would not be affected by this drawback.

Limitations

Selecting seminal frameworks by the number of papers citing the original publication underestimated the importance of the oldest and newest frameworks. Publications influenced by a framework point to its associated theory generation, legitimacy and contributions to nursing knowledge (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya 2013). However, the most used framework is not necessarily the most useful. Further, studies using a framework may not always cite or indicate it in the corresponding publication. This is especially true of the epidemiologic triad of disease, which is not always named as such, despite description of ‘host’, ‘agent’ and ‘environment’ concepts in relation to disease control in many papers (Stirling 2004). As such, it is impossible to know all the ways these frameworks have be used in research and practice to date.

CONCLUSIONS

Going forward, the authors recommend that researchers carefully consider study design elements needed to determine the effectiveness of isolation precautions using one of the three conceptual frameworks discussed above. Future systematic reviews and meta-analyses should frame data abstraction and quality analysis through the Quality Health Outcomes framework as it incorporates elements that can be sensitive to cultural differences. Cross-cultural sensitivities will be important to interpret outcomes of studies conducted in many different countries, especially outcomes such as psychological adverse events of isolation precautions. Administrators, clinicians and researchers may draw from the critical thinking process outlined here when deciding between conceptual frameworks for study design, policymaking or intervention implementation. Hence, this paper has the potential to facilitate future research, international collaboration and multidisciplinary interaction in infection control and other fields.

SUMMARY STATEMENT.

Why is this research or review needed?

Evidence regarding the effectiveness of isolation precautions remains weak due to numerous methodological challenges.

Although infection control is inherently multidisciplinary, nursing practice is an important component; hence, effectiveness research in this field should incorporate nursing perspectives.

Study design and therefore strength of research findings may be improved through use of a conceptual framework congruent with nursing theory.

What are the key findings?

Three conceptual frameworks were identified that may be most applicable to guide study design for isolation precautions effectiveness research.

Which framework can be most useful likely depends on whether the study question necessitates testing multiple interventions, concerns pathogen-specific characteristics and yields cross-sectional or longitudinal data.

The Quality Health Outcomes framework has the advantages of assuming reciprocal relationships and multi-level analysis and incorporating sensitivity to cultural differences.

How should the findings be used to influence policy/practice/research/education?

Future research regarding isolation precautions effectiveness should use a conceptual framework such as one of the three identified in this paper.

This paper outlines a critical thinking process to decide between conceptual frameworks for study design, policymaking or intervention implementation.

Those reviewing and synthesizing evidence regarding isolation precautions should consider the Quality Health Outcomes model to encourage culturally sensitive data abstraction and quality assessment.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: Funding for Catherine Cohen’s work on this paper was generously provided by a National Institutes of Nursing Research institutional training grant (NINR T32NR013454).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Author Contributions:

- substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

- drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Contributor Information

Catherine Crawford, Columbia University School of Nursing, Center for Health Policy.

Jingjing Shang, Columbia University School of Nursing.

References

- Aboelela SW, Saiman L, Stone P, Lowy FD, Quiros D, Larson E. Effectiveness of barrier precautions and surveillance cultures to control transmission of multidrug-resistant organisms: a systematic review of the literature. American Journal of Infection Control. 2006;34(8):484–494. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman G, Rosato AE, Duane TM, Elam K, Sanogo K, Haner C, Kazlova V, Edmond MB. Trial of universal gloving with emollient-impregnated gloves to promote skin health and prevent the transmission of multidrug-resistant organisms in a surgical intensive care unit. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2010;31(5):491–497. doi: 10.1086/651671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman GM, Marra AR, Sessler CN, Smith WR, Rosato A, Laplante JK, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. A controlled trial of universal gloving versus contact precautions for preventing the transmission of multidrug-resistant organisms. American Journal of Infection Control. 2007;35(10):650–655. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo LM, Gardner MJ, Rosenfield RL, Cohen B, Pitetti R. A comparison of dog bite injuries in younger and older children treated in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatrric Emergency Care. 2002;18(3):247–249. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200206000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt JH, Langley RL. Analysis of tractor-related deaths in North Carolina from 1979 to 1988. Journal of Rural Health. 1999;15(3):285–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1999.tb00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Carthon JM, Kutney-Lee A, Sloane DM, Cimiotti JP, Aiken LH. Quality of care and patient satisfaction in hospitals with high concentrations of black patients. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2011;43(3):301–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda JA, Whitehouse T, Cooper B, Hails J, Jones K, Kwaku F, Taylor L, Hayman S, Cookson B, Shaw S, Kibbler C, Singer M, Bellingan G, Wilson APR. Isolation of patients in single rooms or cohorts to reduce spread of MRSA in intensive-care units: prospective two-centre study. Lancet. 2005;365(9456):295–304. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17783-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM, Hong MC, Hsu YH. Administrator self-ratings of organization capacity and performance of healthy community development projects in Taiwan. Public Health Nursing. 2007;24(4):343–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng VCC, Tai JWM, Chan WM, Lau EHY, Chan JFW, To KKW, Li IWS, Ho PL, Yuen KY. Sequential introduction of single room isolation and hand hygiene campaign in the control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care unit. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2010;10:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow K, Wang X, Curtiss R, Castillo-Chavez C., 3rd Evaluating the efficacy of antimicrobial cycling programmes and patient isolation on dual resistance in hospitals. Journal of Biological Dynamics. 2011;5(1):27–43. doi: 10.1080/17513758.2010.488300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark EG. Natural history of syphilis and levels of prevention. British Journal of Venereal Diseases. 1954;30(4):191–197. doi: 10.1136/sti.30.4.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Closs SJ, Tierney AJ. The complexities of using a structure, process and outcome framework: the case of an evaluation of discharge planning for elderly patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1993;18(8):1279–1287. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18081279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MJ, Block C, Levin PD, Schwartz C, Gross I, Weiss Y, Moses AE, Benenson S. Institutional control measures to curtail the epidemic spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: a 4-year perspective. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2011;32(7):673–678. doi: 10.1086/660358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Quarterly. 1966;44(3) Suppl:166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. The Quality of Medical Care. Science. 1978;200(26):856–864. doi: 10.1126/science.417400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois CA, D'Amour D, Tchouaket E, Rivard M, Clarke S, Blais R. A taxonomy of nursing care organization models in hospitals. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:286. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J, Desanto-Madeya S. Contemporary nursing knowledge : analysis and evaluation of nursing models and theories. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner G, Gardner A, O'Connell J. Using the Donabedian framework to examine the quality and safety of nursing service innovation. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014;23(1–2):145–155. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasink LB, Brennan PJ. Isolation precautions for antibiotic-resistant bacteria in healthcare settings. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2009;22(4):339–344. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32832d69b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gbaguidi-Haore H, Legast S, Thouverez M, Bertrand X, Talon D. Ecological study of the effectiveness of isolation precautions in the management of hospitalized patients colonized or infected with Acinetobacter baumannii. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2008;29(12):1118–1123. doi: 10.1086/592697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley RW. The usefulness of a conceptual model in the study of the efficacy of infection surveillance and control programs. Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 1981;3(4):775–780. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.4.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzemer WL, Reilly CA. Variables, variability, and variations research: implications for medical informatics. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 1995;2(3):183–190. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1995.95338871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek C, Faucher MA, Lankford J, Alexander J. Perceptions of care in women sent home in latent labor. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2014;39(2):115–121. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta M, Leventhal A. The epidemiologic pyramid of bioterrorism. Israel Medical Association Journal. 2002;4(7):498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel FS, Rosenfield PL, Anderson NB. Interdisciplinary research : case studies from health and social science. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland KB. Taking off the gloves: toward a less dogmatic approach to the use of contact isolation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48(6):766–771. doi: 10.1086/597090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake ET, Staiger D, Horbar J, Cheung R, Kenny MJ, Patrick T, Rogowski JA. Association between hospital recognition for nursing excellence and outcomes of very low-birth-weight infants. Journal of American Medical Association. 2012;307(16):1709–1716. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landelle C, Pagani L, Harbarth S. Is patient isolation the single most important measure to prevent the spread of multidrug-resistant pathogens? Virulence. 2013;4(2):163–171. doi: 10.4161/viru.22641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavell HR, Clark EG. Preventive medicine for the doctor in his community; an epidemiologic approach. New York: Blakiston Division; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Lin WR, Lu PL, Siu LK, Chen TC, Lin CY, Hung CT, Chen YH. Rapid control of a hospital-wide outbreak caused by extensively drug-resistant OXA-72-producing Acinetobacter baumannii. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences. 2011;27(6):207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBiondo-Wood G, Haber J. Nursing research: Methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby/Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren I, Wahlberg V. The experience of pregnancy: a hermeneutical/phenomenological study. Journal of Perinatal Education. 1999;8(3):12–20. doi: 10.1624/105812499X87196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massanari RM. Nosocomial infections in critical care units: causation and prevention. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. 1989;11(4):45–57. doi: 10.1097/00002727-198903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PH, Ferketich S, Jennings BM. Quality health outcomes model. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1998;30(1):43–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1998.tb01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PH, Lang NM. Framing the Problem of Measuring and Improving Healthcare Quality: Has the Quality Health Outcomes Model Been Useful? Medical Care. 2004;42(2):II4–II11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000109122.92479.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody L, Bradley SF, Galecki A, Olmsted RN, Fitzgerald JT, Kauffman CA, Saint S, Krein SL. Conceptual Model for Reducing Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance in Skilled Nursing Facilities: Focusing on Residents with Indwelling Devices. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;52(5):654–661. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DJ, Diekema DJ, Sepkowitz K, Perencevich EN. Adverse outcomes associated with Contact Precautions: a review of the literature. American Journal of Infection Control. 2009;37(2):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.04.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson SJ, Bredow TS. Middle range theories: Application to nursing research. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reed PG. A treatise on nursing knowledge development for the 21st century: Beyond postmodernism. In: Reed PG, Shearer NBC, editors. Perspectives on Nursing Theory. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reifsnider E. The use of human ecology and epidemiology in nonorganic failure to thrive. Public Health Nursing. 1995;12(4):262–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1995.tb00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie ND. An approach to hospice program evaluation. The use of Donabedian theory to measure success. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 1987;4(5):20–27. doi: 10.1177/104990918700400511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santora M. The New York Times. New York, NY: 2014. New York and New Jersey Tighten Ebola Screenings at Airports. [Google Scholar]

- Scholthof K-BG. The disease triangle: Pathogens, the environment and society. Nature. 2007;5:152–156. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang J, You L, Ma C, Altares D, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Nurse employment contracts in Chinese hospitals: impact of inequitable benefit structures on nurse and patient satisfaction. Human Resources for Health. 2014;12:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheps MC. Approaches to the quality of hospital care. Public Health Rep. 1955;70(9):877–886. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shield R, Rosenthal M, Wetle T, Tyler D, Clark M, Intrator O. Medical staff involvement in nursing homes: development of a conceptual model and research agenda. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2014;33(1):75–96. doi: 10.1177/0733464812463432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L Committee, t.H.I.C.P.A. Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L The Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory, C. Management of multidrug-resistant organisms in health care settings, 2006. American Journal of Infection Control. 2006;35(10):S165–S193. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MN. The best possible condition for nature to act upon host-agent environment relationships. Americal Association of Occupational Health Nurses Journal. 1986;34(3):120–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PW, Bennett G, Bradley S, Drinka P, Lautenbach E, Marx J, Mody L, Nicolle L, Stevenson K. SHEA/APIC guideline: infection prevention and control in the long-term care facility. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2008 Jul;29(9):785–814. doi: 10.1086/592416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling B. Nurses and the control of infectious disease: Understanding epidemiology and disease transmission is vital to nursing care. The Canadian Nurse. 2004;100(9):16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan GC. Evaluating Antonovsky's Salutogenic Model for its adaptability to nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1989;14(4):336–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb03421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JA, Schmitz D, Chung KC. How to practice evidence-based medicine. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010;126(1):286–294. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181dc54ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschudin-Sutter S, Frei R, Dangel M, Stranden A, Widmer AF. Rate of transmission of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing enterobacteriaceae without contact isolation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012;55(11):1505–1511. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde MH. Long-term indwelling urinary catheter care: conceptualizing the research base. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25(6):1252–1261. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273(1):59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zastrow RL. Emerging infections: the contact precautions controversy. American Journal of Nursing. 2011;111(3):47–53. doi: 10.1097/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000395242.14347.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]