Abstract

DNA methylation plays a crucial role in the regulation of gene expression, cell differentiation and development. Previous studies have reported age-related alterations of methylation levels in the human brain across the lifespan, but little is known about whether the observed association with age is confounded by common neuropathologies among older persons. Using genome-wide DNA methylation data from 740 postmortem brains, we interrogated 420,132 CpG sites across the genome in a cohort of individuals with ages from 66 to 108 years old, a range of ages at which many neuropathologic indices become quite common. We compared the association of DNA methylation prior to and following adjustment for common neuropathologies using a series of linear regression models. In the simplest model adjusting for technical factors including batch effect and bisulfite conversion rate, we found 8,156 CpGs associated with age. The number of CpGs associated with age dropped by more than 10% following adjustment for sex. Notably, after adjusting for common neuropathologies, the total number of CpGs associated with age was reduced by approximately 40%, compared to the sex-adjusted model. These data illustrate that the association of methylation changes in the brain with age is inflated if one does not account for age-related brain pathologies.

Keywords: methylation, age, CpG, epigenetics, neuropathology

Introduction

DNA methylation is a widely studied epigenetic mark and plays a crucial role in gene expression regulation, cell differentiation and development [1]. Proper establishment and maintenance of DNA methylation is essential for the development and function of human organisms [2]. Abnormalities in DNA methylation have been associated with a number of non-neurologic and neurologic diseases, including cancer [3], diabetes [4], multiple sclerosis [5], autism [6], schizophrenia [7], Alzheimer's disease (AD) [8], stroke [9], and Parkinson's disease [10]. DNA methylation may also serve as a surrogate marker for other epigenetic changes or for influences of the environment [11], making it a useful tool for probing the etiology of various diseases.

DNA methylation patterns are not fixed but change over time within an individual [12]. Identifying the age-related patterns of DNA methylation in the aging human brain is essential for understanding common age-related neurologic diseases [13]. In a recent review, we found 20 papers published from 1999 to 2014 on the relation of DNA methylation to age [14]. Most studies were relatively small, and the largest array was the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation27 BeadArray. None of the studies investigated the influence of common brain neuropathologies on the relation of methylation to age. Thus, we believe that our study extends prior studies in several important ways. First, our sample size of 740 exceeds by orders of magnitude the largest prior study in human brain, providing great fidelity of the results. Second, our study uses the Illumina 450 BeadArray which generates more than 16 fold more data than the largest prior study to date. Finally, we are able to control for common brain neuropathologies, which to our knowledge has never been done before in examining association of DNA methylation with age. Our results suggest that the association of DNA methylation with age is inflated when common neuropathologies were not taken into account. We believe that these findings will contribute to a better understanding of the change in DNA methylation associated with the aging brain that are distinct from those associated with brain pathology.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants were from two ongoing clinical pathologic studies of aging and dementia: the Religious Orders Study (ROS) and the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP). Detailed information about the two studies can be found elsewhere [15, 16]. The studies share a large core of clinical and post-mortem data collected by the same investigative team, which allows for efficient merging of data. Briefly, ROS began in 1994 and enrolls Catholic clergy aged 55 or older without known dementia at enrollment. The participants were from more than 40 groups across the United States and must agree to organ donation at the time of death and annual clinical evaluation in order to enter the study. MAP began in 1997 and includes participants aged 55 or over without known dementia at enrollments. The participants were from continuous care retirement communities in northeastern Illinois and agreed to annual clinical evaluation and organ donation. By January 1, 2010 when the methylation data were generated, 2,475 participants completed baseline evaluation, and 806 deceased participants underwent autopsies. The overall follow-up rate among survivors exceeds 90% and the autopsy rate exceeds 90%. Participants in both studies sign an informed consent and an anatomic gift act. Both studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center.

Brain Autopsy Procedures

Details of the brain autopsy procedures have been previously reported [17]. Briefly, at the time of autopsy the brainstem and cerebellum are removed, the corpus callosum transected, and one fresh hemisphere of the brain is cut into 1 cm coronal slabs using a Plexiglas jig. Each coronal slab is photographed and examined for visible pathology. Slabs from the hemisphere without visible pathology are placed in a -80°C freezer for long term storage. The alternate hemisphere is fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stored in cryoprotectant solution in a 4°C refrigerator. After fixation, fixed brain slabs and digital images are reviewed for pathology. Tissue blocks are taken from all macroscopic infarcts for confirmation and from specific brain regions for the assessment of common age-related pathologies. All blocks of tissue are embedded in paraffin and cut into 6μm sections for assessment of infarcts, hippocampal sclerosis, and Lewy bodies and 20 μm sections for assessment of amyloid and tangles, and mounted on glass slides for staining.

Age-related Neuropathology

Amyloid, tangles, and Lewy bodies are assessed using immunohistochemistry. Each stain is run on an automated immunohistochemical stainer in precisely timed runs, with identical incubation times. Control sections are included in all runs [18, 19]. Over the course of the study we have used three different antibodies for the assessment of amyloid (4G8, 1:9000; 6F/3D, 1:50; 10D5, 1:300) and one for tangles (AT8, 1:2000), and use diaminobenzidine as the reporter for immunohistochemical analysis, with 2.5% nickel sulfate to enhance immunoreactions product contrast. For the assessment of amyloid we outline 8 brain regions as previously described and perform image analysis to estimate the percent area occupied by amyloid [20]. To reduce the influence of artifactual staining, the cortical areas to undergo image analysis are delineated by hand using the microscopic tools and areas of artifactual staining are excluded from the regions to be sampled. We previously showed that amyloid load measured in this fashion is related to cognition and in persons without cognitive impairment and that the association persists controlling for neurofibrillary tangles [21-23]. The average density of neuronal neurofibrillary tangles per 1mm2 is estimated in the same cortical regions using systematic sampling as previously described [18]. Macroscopic infarcts (i.e., those that can be seen by the naked eye) are found in a subset of brains; each infarct in each individual potentially can be located in one or more of many distinct cortical and/or subcortical brain regions. To assess Lewy bodies, we have used two antibodies during the course of the study (LB509, 1:100; pSyn#64, 1:20,000), and use alkaline phosphatase as the chromogen to provide more contrast for neuromelanin. The presence or absence of neocortical Lewy bodies is determined using sections from the midfrontal, middle temporal, and inferior parietal cortices [19]. Finally, we use hematoxylin and eosin stain to document hippocampal sclerosis (defined as significant neuronal loss and gliosis in CA1 and/or subiculum area of hippocampus as previously described); to confirm the presence of chronic infarcts seen macroscopically; and to determine the presence or absence of microinfarcts. Microscopic infarcts are investigated in 9 separate brain regions and are defined as infarcts that can only be seen under the microscope. All neuropathologic evaluations are conducted by examiners shielded to all clinical data.

DNA Isolation and Generation of DNA Methylation Data

Details have been reported previously [14]. Briefly, 100 mg sections of frozen dorsolateral prefrontal cortex were obtained from autopsied subjects. Sections were thawed on ice, and the gray matter carefully dissected from the white matter. We extracted DNA with the Qiagen (cat: 51306) QIAamp DNA mini protocol. We used 16uL of DNA at a concentration of 50ng/uL as measured by PicoGreen on the Broad Institute's Genomics Platform for the Illumina InfiniumHumanMethylation450 bead chip assay. The DNA Methylation level for each CpG site is presented as a Beta value (β), which is calculated as the ratio of signal from the methylated probe to the sum of both methylated and unmethylated probes and ranges from 0 to 1. Missing values were imputed using a K-nearest neighboring algorithm with k=100.

Quality Control

Data quality was checked at both the probe and sample level, as reported [14]. At the probe level, the p-value criteria reported by Illumina are used for the initial quality check. These p-values represent probe quality relative to background noise. Poor quality probes with detection p-values >0.01 were discarded. In addition, we removed cross-reactive and polymorphic probes. Cross-reactive probes are probes that cross-hybridize with sex chromosomes [24], many of which show strong associations with sex. Polymorphic probes overlap with single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) such that methylation at these sites is affected by the genotype. Since SNPs with very low minor allele frequencies are not likely to have noticeable effects on methylation, we removed polymorphic probes that involve SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.01. At the end of this pipeline, a total of 420,132 autosomal CpGs were retained for the downstream analysis.

At the sample level, we used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to evaluate subject-specific data quality. PCA was performed using a random selection of 50,000 autosomal probes for all the samples. Samples that had first three principal component values within 3 standard deviations from the means were included. Using these criteria, 748 subjects out of a total of 761 subjects were accepted. Eight subjects had poor bisulfite conversion (BC) efficiency, which is defined as having at least 2 of the 10 BC controls that fail to reach a value of 0.8. They were excluded, leaving a total of 740 subjects for the downstream analyses.

Estimation of Cell Types

The proportion of neurons and other cell types in the human cerebral cortex may vary in different brain samples. Neuronal nuclei (NeuN) is a commonly used neuronal marker. To account for cell proportional differences, we used a recently developed technique to quantify the proportion of NeuN+ cells vs. other cell types in each brain sample [25]. This technique allows us to adjust for cell type heterogeneity bias in DNA methylation data. Estimation was done using the CETS package in R. We used nonlinear least-squares to create convex combinations of purified profiles, using the data from the NeuN+ nuclei contained in this package. As a result, we estimated the proportion of NeuN+ for each of the brain sample for the 740 subjects included in this study.

Statistical analysis

To examine the association of age with DNA methylation of an individual CpG, we ran four linear regression models. In each model, the methylation level of a CpG was the response variable, and age was the predictor of interest, with other terms to adjust for potential confounding due to bisulfate conversion rate and batch effect.

We next adjusted for: 1) sex in model 2; 2) sex and six indices of common neuropathologies in model 3, including beta amyloid load, PHFtau tangle density, chronic macro-infarcts and micro-infarcts, neocortical Lewy bodies and hippocampal sclerosis; and 3) sex, common neuropathologies, and cell type mixing proportion in model 4. Multiple comparisons were accounted for using Bonferroni correction.

We employed a novel “Chicago” plot to illustrate the strength and direction of association between DNA methylation and age in a single figure. Unlike the widely-used Manhattan plot which only presents the strength of evidence for an association, the Chicago plot shows, on its vertical axis, –log10p if the association is positive (and hence all relevant points are above the line y=0) and –log10p if the association is negative (and hence all relevant points are below the line y=0). Therefore, this visualization provides valuable information about the direction of association in addition to the significance level of the association.

Statistical analyses were performed using the program R (www.R-project.org) and SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

A total of 740 participants are included in the analyses. Characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. The mean age at death is 88 years (SD=6.7, interquartile range 8.6, and range 66-108) and 36.4% are males. On average, females are older at death (89.2±6.5, range 69-106) than males (86.0±6.5, range 66-108, p<0.0001). Both amyloid load (r=0.18, p<0.0001) and PHFtau tangles (r=0.13, p=0.0004) also are related to age. Participants with macroscopic infarcts are older on average than those without (89.4±6.4 vs. 87.2±6.7; p<0.0001), with similar findings for microscopic infarcts (88.8±7.0 vs.87.7±6.5; p=0.049) and hippocampal sclerosis (91.3±5.9 vs. 87.8±6.6; p=0.0002). An APOE ε4 allele is present in 26.22% subjects. Distributions of the counts of macroscopic and microscopic infarcts are presented in eTable 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the 740 study participants.

| ROS/MAP | |

|---|---|

| Age at death | |

| Mean±SD | 88.0±6.7 |

| Range | 66-108 |

| Male, n (%) | 269 (36.4) |

| Amyloid load (%) (mean± SD ) | 3.5±3.7 |

| Tangles density (mm2) (mean± SD ) | 6.4±8.1 |

| Macroscopic infarct, n (%) | 263 (35.5) |

| Microinfarct, n (%) | 206 (27.8) |

| Neocortical Lewy bodies, n (%) | 75 (10.1) |

| Hippocampal sclerosis, n (%) | 55 (7.4) |

| APOE genotype, n (%)* | |

| ε2ε2 | 6 (0.81) |

| ε2ε3 | 100 (13.51) |

| ε2ε4 | 17 (2.30) |

| ε3ε3 | 433 (58.51) |

| ε3ε4 | 168 (22.70) |

| ε4ε4 | 9 (1.22) |

| CERAD neuritic plaque score, n (%) | |

| Definite AD | 224 (30.27) |

| Probable AD | 247 (33.38) |

| Possible AD | 78 (10.54) |

| No AD | 191 (25.81) |

| Braak score, n (%) | |

| 0 | 9 (1.22) |

| I | 63 (8.51) |

| II | 79 (10.68) |

| III | 220 (29.73) |

| IV | 204 (27.57) |

| V | 158 (21.35) |

| VI | 7 (0.95) |

| NIA-Reagan, n (%) | |

| High likelihood of AD | 128 (17.30) |

| Intermediate Likelihood of AD | 319 (43.11) |

| Low Likelihood of AD | 285 (38.51) |

| No AD | 8 (1.08) |

ROS, the Religious Order Study; MAP, the Memory and Aging Project; APOE, Apolipoprotein E; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease; NIA, National Institute on Aging.

APOE genotype is available for 733/740 subjects.

CERAD neuritic plaque score is a semiquantitative measure of neuritic plaques (Mirra, S.S., M.N. Hart, and R.D. Terry, Making the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. A primer for practicing pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 1993. 117(2): p. 132-44)

Braak score is semiquantitative measure of neurofibrillary tangles (Braak, H. and E. Braak, Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol, 1991. 82(4): p. 239-59)

NIA-Reagan diagnosis of AD (Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. The National Institute on Aging, and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer's Disease. Neurobiol Aging, 1997. 18(4 Suppl): p. S1-2)

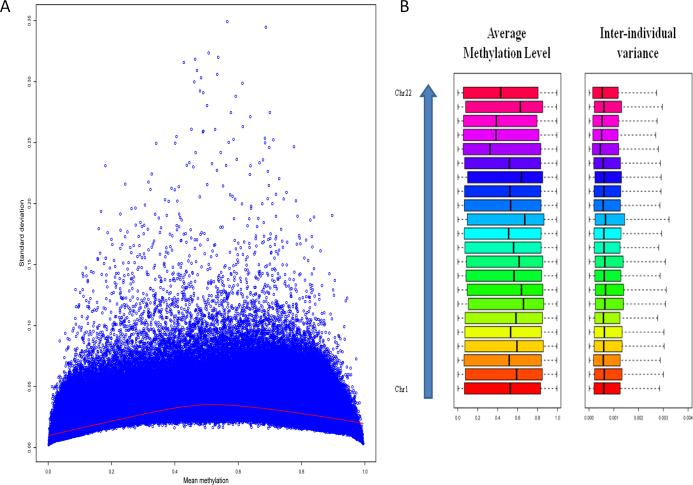

Inter-individual variation in human brain DNA methylation

We find relatively lower variability in DNA methylation for CpG sites with very low or high level of methylation, and higher variability for CpG sites with intermediate level of methylation (Figure 1A). A recent study of DNA methylation in the human peripheral blood monocytes reported a higher density of variable regions in chromosomes 13 and 21, and lower density of variable regions in chromosomes 1 and 3 [26]. In human brain, however, we do not find dramatic differences in inter-individual variances of DNA methylation across chromosomes (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Inter-individual variation in DNA methylation in the human brain.

A. Level and standard deviation of methylation.

The red curve is the smooth curve fitted by loess.

B. Inter-individual variation in methylation by chromosome

Association of age with human brain DNA methylation

We perform a genome-wide association analyses to examine the relationship of age to DNA methylation in the human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. We subsequently evaluate our results by adjusting for different sets of important covariates in a series of regression models.

In the simplest model, adjusted for technical factors including batch effects and bisulfite conversion rate, we find 8,156 CpGs associated with age. Consistent with the strong effect of sex on methylation and the differential survival of men and women in older age, about 17% of CpGs no longer show associations with age after further adjusting for sex. Interestingly, an additional 569 CpGs become associated with age, leading to a total of 7,336 CpGs. This represents more than a 10.1% reduction of the number of CpGs associated with age. We next adjust for six common neuropathologic indices. In this model, 2,862 CpGs are no longer significant, and only 60 new CpGs are identified, leading to a total of 4,534 CpGs. This represents nearly a further 40% decrease compared to the model adjusted for sex. Finally, after further adjusting for an estimate of the proportion of neuronal cells in each sample which is also likely to be associated with age and neuropathologic indices [25], another 848 CpGs are no longer associated with age, whereas 577 new CpGs are identified. The final model identified 4,263 CpGs associated with age. This represents about half of the CpGs identified in the simplest model, and includes more than 600 CpGs that were unmasked compared to the simplest model, illustrating that the significant associations are markedly inflated in the absence of the adjustment.

The details of the number of significant CpGs under each model are given in Table 2, and Figure 2A and 2B compares the association of age with DNA methylation by chromosome with and without adjusting for common neuropathologies. The Chicago plot illustrates that the directionality of the associations is quite different. The positive associations with age which rise vertically from 0 are both more numerous and stronger with many values reaching 10-20 and some 10-40. By contrast, the negative associations which fall below 0 are fewer and nearly all less than 10-10. Interestingly, Figure 2C illustrates the mean level of DNA methylation and association of DNA methylation with age for all the CpGs associated with age in the fully adjusted models. The figure illustrates that level of DNA methylation varies with the directionality of association with age. Specifically, we found that among the significant CpGs with positive associations with age, a majority (92.7%) are hypo-methylated (mean methylation<0.5). By contrast, among the significant CpGs showing negative association with age, a majority (65.3%) are hyper-methylated.

Table 2.

Number of CpGs showing significant association with age in each model.

| Model | Common | New | No longer significant | Total # of significant CpGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8,156 | 8,156 | ||

| 2 | 6,767 | 569 | 1,389 | 7,336 |

| 3 | 4,474 | 60 | 2,862 | 4,534 |

| 4 | 3,686 | 577 | 848 | 4,263 |

Total number of CpGs interrogated: 420,132

Common: # of CpGs showing significant association with age both in this model and in the previous model (e.g., significant in both model 2 and model 1)

New: # of CpGs showing significant association with age in this model but not in the previous model (e.g., significant in model 2 but not in model 1)

No longer significant: # of CpGs showing significant association with age in the previous model but not in this model (e.g., significant in model 1 but not in model 2)

Figure 2. Association of DNA methylation with age.

Each point on the plot represents association of an individual CpG. The horizontal coordinate is the location within chromosome. The vertical coordinate is –log10p if the CpG's association with age is positive and log10p if the association is negative. The dashed line corresponds to the significance level using Bonferroni correction (1.19×10-07). The observed level of significance was calculated from linear regression with methylation being the response and age being the predictor.

A. We adjusted for batch effect and bisulfite conversion.

B. We further adjusted for gender, cell type and six neuropathologies (amyloid, tangles, gross infarct, cortical Lewy bodies, cerebral Infarcts and hippocampal sclerosis).

C. Mean level of methylation and association of DNA methylation with age.

The coefficient displayed for the x-axis is re-scaled to represent the change in methylation per decade.

We also examine the distribution of significant CpGs by genomic location. Of the 135,303 CpG islands across genome, 1734 islands harbor at least one CpG with a significant association with age. We find that compared with CpG islands which have the highest percentage of significant CpGs (2.1%), less than 0.5% of CpGs in the shelves and non-CpG related regions show significant associations with age. Further, only CpG islands show an enrichment in association (4.89×10-176; see eTable 2 in the online supplementary file). We also generate a Manhattan plot for all CpGs in CpG islands (eFigure 1). Both the Manhattan plot and the enrichment analysis by CpG islands indicate that some genomic locations in the CpG islands are enriched for significant CpGs (e.g., some CpG islands on chromosome 6, see eTable 3).

Discussion

We interrogated 420,132 CpG sites across the genome using brain DNA methylation data from 740 older persons between the ages of 66 and 108. We identify 8,156 CpG sites showing signification association with age after adjustment for technical factors. The number of significant CpGs decreased by half to 4,263 in the fully adjusted model where we further controlled for sex, six common age-related neuropathologies, and cell type mixing proportion. This study has by far the largest sample size as well as the total number of CpG sites interrogated in investigating the association of age with post-mortem brain DNA methylation. Further, to our knowledge, this is the first study to adjust for the potential confounding effects of common neuropathologies. Our findings suggest that numerous CpGs associated with age result from confounding and that some CpGs associated with age are masked by confounding.

Our recent study examined DNA methylation in 28 known susceptibility loci for AD and found that brain DNA methylation in SORL1, ABCA7, HLA-DRB5, SLC24A4, and BIN1 was associated with pathological AD [27]. We and others have also detected DNA methylation associations with AD pathology in methylome wide association studies [28, 29]. AD-related alteration in methylation has also been observed in previous studies [8, 30, 31]. Similarly, changes in DNA methylation has been reported in persons with other neuropathologies such as dementia with Lewy bodies [32] and hippocampal sclerosis [33]. These results suggest that the pathogenesis of AD and other neurological diseases might influence the brain's epigenome, and therefore, these common neuropathologies are potentially important confounding factors in the analysis of the association of DNA methylation with age.

Compared with the model adjusting for technical factors, age and sex (model 2), in the model with further adjusting for the six common neuropathologies (model 3), the methylation in many genes is no longer significantly associated with age. For example, brain DNA methylation in ABCA7 was reported to be associated with pathologic AD [27]. The one CpG (cg02308560) in ABCA7 that shows a significant association with age in model 2 (p=1.63×10-8), is greatly attenuated in model 3 (p=6.09×10-5). Similarly, a recent study reported association of genetic variants in TRIB1 with microscopic infarct pathology [34]. We find that no CpG in TRIB1 remain associated with age after controlling for neuropathologies. A polymorphism in ABCC9 was found to be associated with hippocampal sclerosis pathology [35]. Again, we find that one CpG (cg01085837) showing an association with age in model 2 is no longer significant in model 3. These observations highlight the possibility of false positive findings when neuropathologies are not taken into account in the study of the association of DNA methylation with age. The extent to which subclinical disease affects the association of age with DNA methylation in other tissues is unknown but our findings warrant caution with all tissues that may harbor disease.

The regression coefficients of age estimated from the regression analyses are generally smaller than previously reported [36]. This is consistent with previous findings that methylation exhibits the strongest age difference in the prenatal period, but less so in adults and as one ages [37]. This suggests that overall variation in DNA methylation is the smallest among old persons. The Chicago plot clearly indicates that most of the significant CpGs (92.4%) are hypo-methylated and show positive associations with age such that older brains are less methylated (Figures 2A, 2B, and 2C). This is consistent with findings from a recent study which reported that the majority of age related CpGs showed positive association and were generally hypo-methylated across various human tissues [38].

In the same cohorts, we have published data on coexisting brain diseases [17, 39]. Briefly, we found that nearly every brain has some PHFtau tangles, about 80% have amyloid, and about a third have macro- and another third micro-infarcts; about 10% have cortical Lewy bodies and nearly 10% have hippocampal sclerosis. Thus, many people have subclinical pathology, including many with more than one pathology.

Our study has some limitations. We performed DNA methylation on a chunk of brain tissue with many cell types. Cellular composition of human brains is dynamic and may change with chronological aging (e.g., the proportion of neurons to glia) [40]. We address this by controlling for cell type, although this is likely imperfect. Our study was limited to one brain region (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), and the findings should be extrapolated to other brain regions with caution. There is only limited information in the literature regarding DNA methylation patterns in other brain regions or other tissues [41-44]. Previous studies found different types of age-related methylation profiles associated with age that suggest the rate of change in DNA methylation varies at different age stages [45]. Since all our data were obtained from elderly participants, it is only possible to examine the relation of DNA methylation to age in older subjects aged 70-100, the ages at which neuropathologies become very common. We did not control for APOE status in this study. However, our recent research indicates that APOE is strongly associated with amyloid load and PHFtau tangles such that there is likely to be little residual confounding [46]. This study is limited to non-Hispanic whites, and our results might not be generalized to other racial or ethnic groups. Our results indicate that the association pattern may vary across genomic locations. It will be important to explore this and other possible alterations in gene expression in future papers.

Supplementary Material

eFigure 1. Association of DNA methylation with age in CpG islands across genome.

Each point on the plot represents association of an individual CpG. The horizontal coordinate is the location within chromosome. The observed level of significance was calculated from linear regression with methylation being the response and age being the predictor, adjusting for age, gender, batch effect, bisulfite conversion, cell type and the six neuropathologies. The dashed line corresponds to the significance level using Bonferroni correction (1.19×10-07).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants in the Rush Memory and Aging Project and Religious Order Study, and the faculty and staff of the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center.

The study was supported by NIH/NIA grants P30AG10161, R01AG15819, R01AG17917, R01AG36042, U01AG46152 and the Illinois Department of Public Health. The funders had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest disclosures:

All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this manuscript.

References

- 1.Robertson KD, Jones PA. DNA methylation: past, present and future directions. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(3):461–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16(1):6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feinberg AP, Tycko B. The history of cancer epigenetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(2):143–53. doi: 10.1038/nrc1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volkmar M, et al. DNA methylation profiling identifies epigenetic dysregulation in pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetic patients. EMBO J. 2012;31(6):1405–26. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urdinguio RG, Sanchez-Mut JV, Esteller M. Epigenetic mechanisms in neurological diseases: genes, syndromes, and therapies. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(11):1056–72. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagarajan RP, et al. Reduced MeCP2 expression is frequent in autism frontal cortex and correlates with aberrant MECP2 promoter methylation. Epigenetics. 2006;1(4):e1–11. doi: 10.4161/epi.1.4.3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mill J, et al. Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(3):696–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mastroeni D, et al. Epigenetic changes in Alzheimer's disease: decrements in DNA methylation. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(12):2025–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baccarelli A, et al. Ischemic heart disease and stroke in relation to blood DNA methylation. Epidemiology. 2010;21(6):819–28. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181f20457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masliah E, et al. Distinctive patterns of DNA methylation associated with Parkinson disease: Identification of concordant epigenetic changes in brain and peripheral blood leukocytes. Epigenetics. 2013;8(10) doi: 10.4161/epi.25865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat Genet. 2003;33(Suppl):245–54. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson B. Impact of aging on DNA methylation. Ageing Res Rev. 2003;2(3):245–61. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(03)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang SC, Oelze B, Schumacher A. Age-specific epigenetic drift in late-onset Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett DA, et al. Epigenomics of Alzheimer's Disease. Translational Research. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.05.006. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett DA, et al. Overview and findings from the Religious Orders Study. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9(6):628–45. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett DA, et al. Overview and findings from the rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9(6):646–63. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider JA, et al. The neuropathology of probable Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(2):200–208. doi: 10.1002/ana.21706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett DA, et al. Neurofibrillary tangles mediate the association of amyloid load with clinical Alzheimer disease and level of cognitive function. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(3):378–84. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider JA, et al. Cognitive impairment, decline and fluctuations in older community-dwelling subjects with Lewy bodies. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 10):3005–14. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson RS, et al. Life-span cognitive activity, neuropathologic burden, and cognitive aging. Neurology. 2013;81(4):314–321. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829c5e8a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett DA, et al. Neurofibrillary tangles mediate the association of amyloid load with clinical Alzheimer disease and level of cognitive function. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(3):378–384. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett DA, et al. Education modifies the association of amyloid but not tangles with cognitive function. Neurology. 2005;65(6):953–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000176286.17192.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett DA, et al. Relation of neuropathology to cognition in persons without cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(4):599–609. doi: 10.1002/ana.23654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YA, et al. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics. 2013;8(2):203–9. doi: 10.4161/epi.23470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guintivano J, Aryee MJ, Kaminsky ZA. A cell epigenotype specific model for the correction of brain cellular heterogeneity bias and its application to age, brain region and major depression. Epigenetics. 2013;8(3):290–302. doi: 10.4161/epi.23924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen H, et al. Characterization of the DNA methylome and its interindividual variation in human peripheral blood monocytes. Epigenomics. 2013;5(3):255–69. doi: 10.2217/epi.13.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu L, et al. Association of Brain DNA Methylation in SORL1, ABCA7, HLA-DRB5, SLC24A4, and BIN1 With Pathological Diagnosis of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Jager PL, et al. Alzheimer's disease: early alterations in brain DNA methylation at ANK1, BIN1, RHBDF2 and other loci. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(9):1156–63. doi: 10.1038/nn.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lunnon K, et al. Methylomic profiling implicates cortical deregulation of ANK1 in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(9):1164–70. doi: 10.1038/nn.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chouliaras L, et al. Consistent decrease in global DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation in the hippocampus of Alzheimer's disease patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(9):2091–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao JS, et al. Epigenetic modifications in frontal cortex from Alzheimer's disease and bipolar disorder patients. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2 doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandez AF, et al. A DNA methylation fingerprint of 1628 human samples. Genome Res. 2012;22(2):407–19. doi: 10.1101/gr.119867.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller-Delaney SF, et al. Differential DNA methylation profiles of coding and non-coding genes define hippocampal sclerosis in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2014 doi: 10.1093/brain/awu373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chou SH, et al. Genetic susceptibility for ischemic infarction and arteriolosclerosis based on neuropathologic evaluations. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;36(3):181–8. doi: 10.1159/000352054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson PT, et al. ABCC9 gene polymorphism is associated with hippocampal sclerosis of aging pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(6):825–43. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christensen BC, et al. Aging and environmental exposures alter tissue-specific DNA methylation dependent upon CpG island context. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Numata S, et al. DNA methylation signatures in development and aging of the human prefrontal cortex. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(2):260–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Day K, et al. Differential DNA methylation with age displays both common and dynamic features across human tissues that are influenced by CpG landscape. Genome Biol. 2013;14(9):R102. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-9-r102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyle PA, et al. Much of late life cognitive decline is not due to common neurodegenerative pathologies. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(3):478–489. doi: 10.1002/ana.23964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terry RD, DeTeresa R, Hansen LA. Neocortical cell counts in normal human adult aging. Ann Neurol. 1987;21(6):530–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410210603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ladd-Acosta C, et al. Common DNA methylation alterations in multiple brain regions in autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(8):862–71. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Illingworth RS, et al. Inter-individual variability contrasts with regional homogeneity in the human brain DNA methylome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(2):732–44. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hernandez DG, et al. Distinct DNA methylation changes highly correlated with chronological age in the human brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(6):1164–1172. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ziller MJ, et al. Charting a dynamic DNA methylation landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2013;500(7463):477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siegmund KD, et al. DNA methylation in the human cerebral cortex is dynamically regulated throughout the life span and involves differentiated neurons. PLoS One. 2007;2(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu L, et al. Disentangling the effects of age and APOE on neuropathology and late life cognitive decline. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(4):819–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.10.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Association of DNA methylation with age in CpG islands across genome.

Each point on the plot represents association of an individual CpG. The horizontal coordinate is the location within chromosome. The observed level of significance was calculated from linear regression with methylation being the response and age being the predictor, adjusting for age, gender, batch effect, bisulfite conversion, cell type and the six neuropathologies. The dashed line corresponds to the significance level using Bonferroni correction (1.19×10-07).