Abstract

Cells of the osteoblast lineage play an important role in regulating the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche and early B cell development in animal models, perhaps via parathyroid hormone (PTH) dependent mechanisms. There are few human clinical studies investigating this phenomenon. We studied the impact of long-term daily teriparatide (PTH 1-34) treatment on cells of the hematopoietic lineage in postmenopausal women. Twenty-three postmenopausal women at high risk of fracture received teriparatide 20 mcg SC daily for 24 months as part of a prospective longitudinal trial. Whole blood measurements were obtained at baseline, 3, 6, 12, and 18 months. Flow cytometry was performed to identify hematopoietic subpopulations, including HSCs (CD34+/CD45(moderate); ISHAGE protocol) and early transitional B cells (CD19+, CD27−, IgD+, CD24[hi], CD38[hi]). Serial measurements of spine and hip bone mineral density as well as serum P1NP, osteocalcin, and CTX were also performed. The average age of study subjects was 64 ± 5. We found that teriparatide treatment led to an early increase in circulating HSC number of 40% ± 14% (p=0.004) by month 3, which persisted to month 18 before returning to near baseline by 24 months. There were no significant changes in transitional B cells or total B cells over the course of the study period. In addition, there were no differences in complete blood count profiles as quantified by standard automated flow cytometry. Interestingly, the peak increase in HSC number was inversely associated with increases in bone markers and spine BMD. Daily teriparatide treatment for osteoporosis increases circulating HSCs by 3 to 6 months in postmenopausal women. This may represent a proliferation of marrow HSCs or increased peripheral HSC mobilization. This clinical study establishes the importance of PTH in the regulation of the HSC niche within humans.

Keywords: hematopoietic stem cell niche, parathyroid hormone, teriparatide, B cell lymphopoiesis

INTRODUCTION

The bone microenvironment is critically important to sustaining bone marrow, although the mechanisms by which this occurs have not been fully defined. In particular, the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche is thought to be modulated by both osteoblasts and osteoprogenitors within the endosteal and perivascular stroma (1-3). Increasing evidence suggests that osteoblasts also regulate the development of the lymphoid, erythroid, and myeloid lineages (4, 5).

In vitro and animal studies have demonstrated that both hematopoiesis and the HSC niche may be modulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH) activity within osteoblasts. In vitro, murine calvarial osteoblasts treated with PTH were able to support B-cell differentiation (6). Studies of transgenic mice have demonstrated that disruption of the PTH receptor via Gsα ablation early within the osteoblast lineage leads to a reduction in early B cell lineages (7). Conversely, constitutive activation of the PTH receptor in osteoblasts increased HSC number and activity (8). Exogenous treatment with PTH in mouse models expands HSC number within the bone marrow (8), induces HSC mobilization into peripheral circulation (9), and leads to superior engraftment in mouse models of bone marrow transplantation (8, 10). Lastly, a 14-day study of teriparatide (PTH 1-34) administration in postmenopausal women found differences in gene expression within osteoprogenitor cells as compared to untreated controls(11).

There are little data from human clinical studies investigating the physiologic actions of PTH on hematapoiesis and HSCs. We sought to determine the long-term effect of teriparatide treatment on peripheral HSCs and early B cell lineages in postmenopausal women receiving treatment for osteoporosis.

METHODS

Study Population

We studied a subset of women who received teriparatide monotherapy as part of the Denosumab and Teriparatide Administration (DATA) study. Details of the study recruitment and protocol have been previously described (12). Briefly, postmenopausal women with high fracture risk were recruited for a 24-month randomized controlled trial of teriparatide monotherapy, denosumab monotherapy, or combination therapy. We defined high fracture risk according to the following criteria: T score −2.5 or less at the spine, hip, or femoral neck; T score −2.0 or less with at least one BMD-independent risk factor (fracture after age 50 years, parental hip fracture after age 50 years, previous hyperthyroidism, inability to get up from a chair with arms raised, or current smoking); or T score −1.0 or less with history of fragility fracture. Women were excluded for use of oral bisphosphonates in previous 6 months, any use of parenteral bisphosphonates, or use of other osteoporosis medications for previous 3 months. Women were required to have 25-hydroxyvitamin D ≥ 20 ng/ml (50 nmol/L) prior to enrolling in the study. Subjects randomized to the teriparatide monotherapy arm were invited to participate in this optional substudy. Twenty-three women provided written consent to participate. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners HealthCare Systems.

Experimental Protocol

Women in this substudy received open-label teriparatide 20 mcg SC daily for 24 months. Blood samples were taken at 0, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. Complete blood count with standard differential was performed to define total counts of white blood cells, lymphocytes, monocytes, red blood cells, and platelets using automated flow cytometry (Sysmex XE-5000, Kobe, Japan). Additional flow cytometry was performed to further define lymphocyte subpopulations and HSC number, as detailed below. Serum samples were batched for analysis of osteocalcin (Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD), P1NP (Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland), and C-telopeptide, CTX (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Assessments of lumbar spine and femoral bone mineral density (BMD) were performed on a Hologic QDR 4500A densitometer (Hologic, Waltham, MA) at each study visit.

Flow cytometry analyses

Identification of HSC number, as well as B and T lymphocyte subpopulations was performed using a FACSCanto™ II cytometer (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) running FACSDiva™ (BD Biosciences, version 6.1.3) acquisition and analysis software. All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences unless otherwise specified.

For quantification of HSCs, 100 uL of whole blood was added to each of a 3-tube panel containing 2 identical tubes with CD34-PE and CD45-PerCP and 1 negative control tube with mouse IgG1-PE and CD45 PerCP. The antibody and sample mixture was incubated for 15 minutes and afterwards 1 mL of 1X BD FACS Lysing solution was added and incubated for 10 minutes. The tubes were centrifuged at 500g, the supernatant was aspirated and 500 uL of 1% Paraformaldehyde fixative was added to each of the tubes. The International Society of Hematotherapy and Graft Engineering (ISHAGE) guidelines for CD34+ cell determination by flow cytometry were followed for the acquisition and analysis of the data (13). As per ISHAGE guidelines, at least 100,000 CD45+ events were collected. Side Scatter(low)/CD34+/CD45(moderate) events with appropriate Forward Scatter were selected as the HSC population. The CD34+ HSC value was calculated by taking the average CD34+ value from the first two tubes of the panel and subtracting out any events that stained positively for the IgG1 negative control.

For quantification of lymphocyte subpopulations, 100 uL of peripheral blood that had been washed three times with Phosphate Buffered Saline was added to test tube containing CD24-FITC, IgD-PE, CD38-PerCP (BioLegend Co., San Diego, CA), CD3-PE-Cy7, CD27-APC, CD19-APC-H7, CD14-Pacific Blue and CD45 AmCyan. The antibody and sample mixture was incubated for 15 minutes and afterwards 1 mL of 1X BD FACS Lying solution was added and incubated for 10 minutes. The tubes were centrifuged at 500g, the supernatant was aspirated and 500 uL of 1% Paraformaldehyde fixative was added to each of the tubes. The lymphocyte population was determined by placing a gate around the CD45+/Side Scatter(low) events. Total T cells were defined by gating on CD3+CD19− events and total B cells were defined by gating on CD19+CD3− events. We also identified a population of early stage “transitional” B cells as the subset of cells derived from the total CD19+ B cell population as CD27−, IgD+, CD24[hi], CD38[hi]. Previous literature has identified this subpopulation to be circulating immature B cells (14).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline data are summarized as mean ± SD and longitudinal data are summarized as mean ± SEM. Changes over time within hematopoietic subsets were analyzed with linear mixed models with random subject intercepts and fixed effect of time (SAS 9.2, PROC MIXED). Adjustment for multiple comparisons between timepoints was performed using Dunnett’s test, and Dunnett-adjusted p-values are reported for longitudinal data. Three subjects dropped out over the course of the 24-month study; their data are included up until the time of their discontinuation from teriparatide. Five subjects did not have HSC flow cytometry evaluation at baseline and were therefore excluded from longitudinal HSC analyses. Interim analyses demonstrated a lack of effect on lymphocyte subsets at 12 months and therefore additional flow cytometry analyses of T cell, B cell, and transitional B cell subpopulations were not continued beyond that timepoint. Changes in hematopoietic subsets were correlated with baseline bone density and bone markers, and change in bone density and bone markers using Pearson’s correlations (SAS 9.2, PROC CORR). Given that changes in HSCs were nonlinear, we focused on correlations of initial changes in HSCs with changes in bone markers and BMD. HSCs were also correlated with baseline age, PTH, and 25OHD. Analyses were performed with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Resulting values of p < 0.05 (two-sided) were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

At study entry, the average age of the women was 64 ± 5 years (Table 1). Thirty-nine percent of women had previously taken oral bisphosphonates, although use was discontinued on average 44 ± 37 months prior to study entry.

Table 1.

| Baseline characteristics, mean ± SD (n=23) | |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 64 ± 5 |

| Height (in) | 63 ± 3 |

| Weight (lbs) | 146 ± 25 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26 ± 4 |

| Previous oral bisphosphonate use (%) | 39% |

| Duration of use (months) | 41 ± 30 |

| Time since discontinuation (months) | 44 ± 37 |

| 25OH-VitD (ng/ml) | 31 ± 8 |

| CTX (ng/ml) | 0.35 ± 0.15 |

| P1NP (mcg/l) | 61 ± 22 |

| Osteocalcin (ng/ml) | 46 ± 20 |

| DXA BMD (g/cm2) | |

| Posterior-anterior lumbar spine | 0.845 ± 0.107 |

| Total hip | 0.767 ± 0.063 |

| Femoral neck | 0.652 ± 0.062 |

| T-score | |

| Posterior-anterior lumbar spine | −1.8 ± 0.6 |

| Total hip | −1.4 ± 0.5 |

| Femoral neck | −1.8 ± 1.0 |

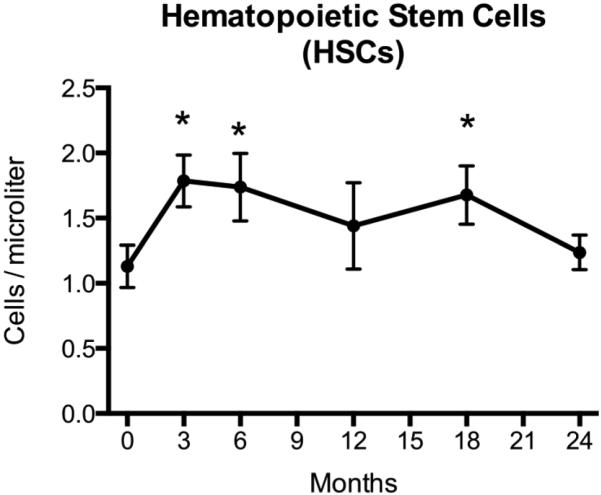

Peripheral HSC number increased by 40% ± 14% after 3 months of TPTD administration (p=0.004, Figure 1), which was the earliest timepoint studied. The increase in HSCs was greatest after 3 months of therapy, but remained significantly above baseline at the 6 month (p=0.013) and 18 month (p=0.044) timepoints (Figure 1). HSC number returned to baseline by the 24-month time point. A similar pattern of change in HSCs was observed in the subset of women (n=9) who had never been exposed to bisphosphonates (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1. Peripheral Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) during 24 months of teriparatide treatment.

HSCs were assessed by flow cytometry at months 0 (n=18), 3 (n=18), 6 (n=17), 12 (n=13), 18 (n=15), and 24 (n=15) after initiation of daily teriparatide. Increases in HSCs over baseline are evident at months 3 (p=0.004), 6 (p=0.013), and 18 (p=0.044; * indicates statistical significance after Dunnett’s adjustment for multiple comparisons). HSC number declines towards baseline by 24 months of daily teriparatide treatment. Data presented are mean ± SEM.

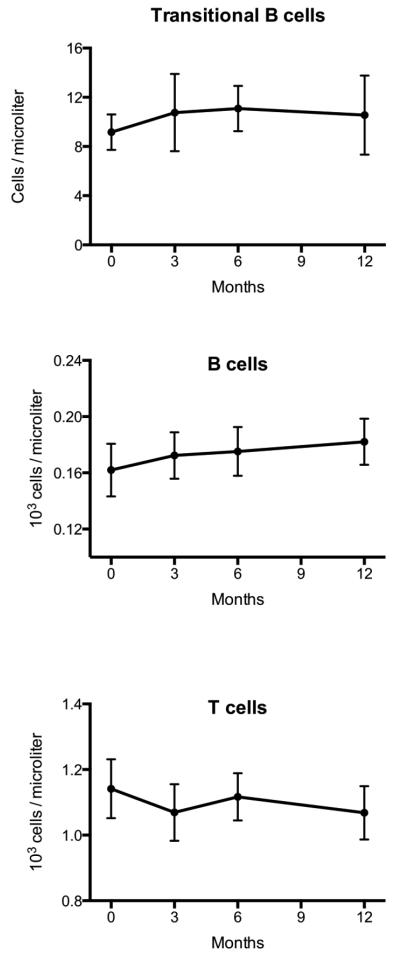

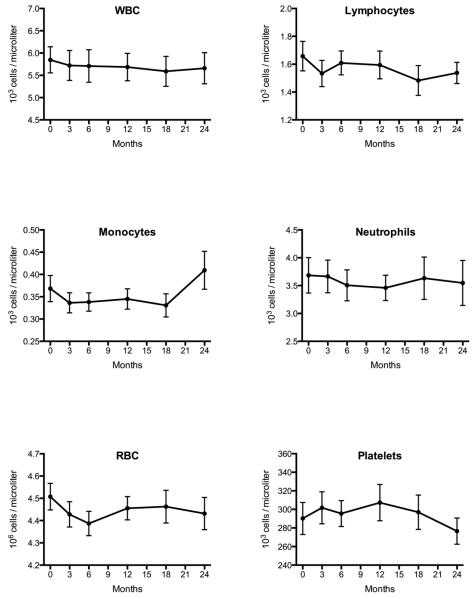

There were no significant changes in the total B cell, total T cell, or transitional B cell subpopulations throughout 12 months of teriparatide administration (Figure 2). Similarly, there were no detectable changes in the numbers of total white cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, red blood cells, or platelets throughout the 24-month study (Figure 3).

Figure 2. B and T lymphocyte subpopulations during 12 months of teriparatide treatment.

B and T lymphocytes were assessed by flow cytometry at months 0 (n=23), 3 (n=22), 6 (n=21), and 12 (n=19) after initiation of daily teriparatide. No significant changes were noted in early transitional B cells, total B cells, or total T cells in response to daily teriparatide treatment. Data presented are mean ± SEM.

Figure 3. Other hematopoietic lineages during 24 months of teriparatide treatment.

Complete blood counts with differentials were assessed by standard automated flow cytometry at months 0 (n=23), 3 (n=23), 6 (n=22), 12 (n=21), 18 (n=20), and 24 (n=20) after initiation of daily teriparatide. No significant changes were noted in total white blood cells, lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, red blood cells, or platelets in response to daily teriparatide treatment. Data presented are mean ± SEM.

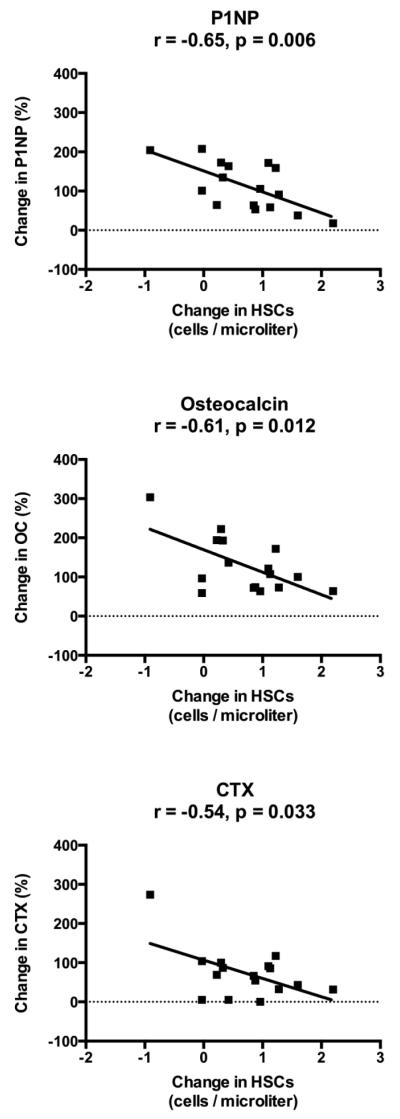

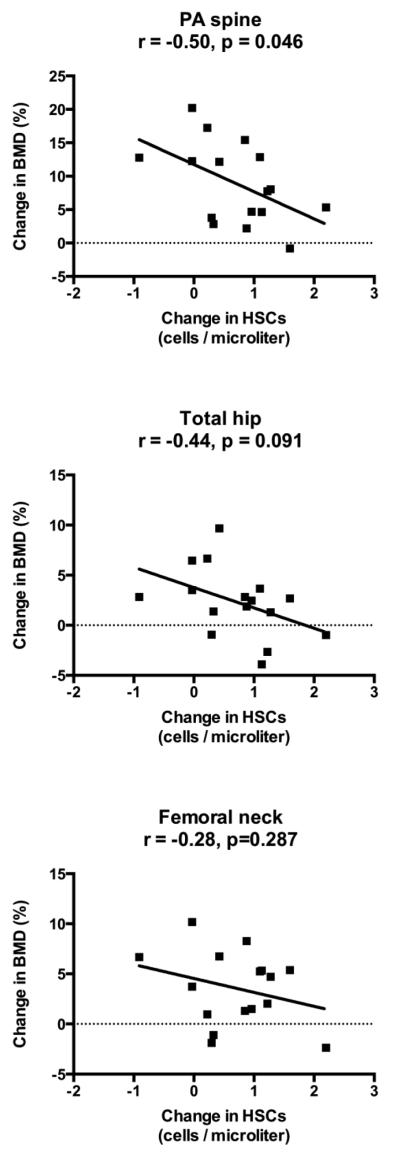

As expected, bone mineral density increased in response to 24 months of teriparatide (spine: 8.8 ± 1.3%; total hip: 1.8 ± 0.8%; femoral neck: 3.2 ± 0.8%; p≤0.005 for all). Teriparatide treatment also led to anticipated changes in bone turnover markers, with an early increase in bone markers that peaked at 6 months and gradually declined between 12 and 24 months (% increase at 6 months for P1NP: 195 ± 35%; OC: 150 ± 29%; CTX: 138 ± 29%; p<0.001 for all). However, peak change in HSCs at 3 months was inversely associated with changes in P1NP (r = −0.65, p=0.006), osteocalcin (r = −0.61, p=0.012), and CTX (r = −0.54, p=0.033) at 3 months (Figure 4). Similarly, changes in HSCs and bone turnover markers at 6 months were also inversely associated (P1NP: r = −0.68, p=0.005; osteocalcin: r = −0.59, p=0.022; CTX: r = −0.66, p=0.005). Furthermore, peak change in HSCs at 3 months was negatively associated with the change in spine BMD at 24 months (r = −0.50, p=0.046), but not total hip or femoral neck BMD (Figure 5). There were no associations between baseline HSCs or change in HSCs and age, 25-hydroxyvitamin D level, endogenous PTH level, or baseline bone mineral density at any site.

Figure 4. Inverse correlation of change in HSCs with change in bone markers.

Both HSCs and bone markers increased during the initial period of teriparatide treatment before reaching a plateau and subsequently declining. Peak change in HSCs at 3 months was inversely correlated with change in P1NP, Osteocalcin, and CTX at 3 months.

Figure 5. Inverse correlation of change in HSCs with change in bone density.

HSC number during teriparatide treatment peaked at 3 months, whereas bone density increased throughout the 24 months. Peak change in HSCs at 3 months was inversely correlated with change in PA spine BMD at 24 months, but was not associated with change in total hip or femoral neck BMD.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective longitudinal study, 3 months of daily teriparatide administration in postmenopausal women increased circulating HSCs, and these increases remained evident after 6 and 18 months of therapy. The expected PTH-induced increases in bone turnover markers and bone mineral density were inversely associated with the peak increase in HSCs. No changes in B lymphocytes were observed, including within the early transitional B cell subpopulation.

This is the first human study to examine the effect of PTH on hematologic cells in a non-oncologic population. Two early phase I/II studies examined short-course high-dose PTH treatment as an adjunct for autologous stem cell transplantation (15) or umbilical cord transplantation (16) in the treatment of hematologic malignancies. In both studies, high-doses of teriparatide (up to 100 mcg/day) were given for 28 days or less, and were given in conjunction with G-CSF, a stem cell mobilizing agent. These studies, both powered for safety endpoints only, were unable to determine whether PTH improved stem cell mobilization into peripheral circulation or engraftment after transplantation. Another study of short-course teriparatide (40 mcg/day for 14 days) in postmenopausal women found differences in gene expression within osteoprogenitor cells as compared to untreated controls (11). In the current study, we demonstrated that long-term teriparatide treatment at FDA-approved osteoporosis dosing (20 mcg/day) increases circulating HSCs in the absence of G-CSF. This result is consistent with findings from animal studies (8, 9) and provides important insights into the physiologic regulation of the HSC niche by parathyroid hormone.

While our data provide clear evidence for enhanced early mobilization of HSCs after PTH treatment, we could not determine whether this effect is due to enhanced egress of HSCs into the circulation or true bone marrow expansion of the HSC population. Animal studies, however, suggest that short-term PTH administration increases circulating HSC number without depleting marrow space HSCs (9). Future studies should examine clinical bone marrow specimens in long-term studies of PTH treatment to confirm the preservation and/or expansion of HSCs within the marrow.

Interestingly, we observed that circulating HSCs increased less in women who respond to teriparatide most vigorously by bone markers and bone density. This unexpected result suggests that the effects of PTH on bone mass and HSC mobilization may be inversely mediated through common molecular or cellular mechanisms. One common pathway may be the Wnt signaling cascade, which has been implicated in the anabolic actions of PTH (17, 18). Osteoblastic overexpression of Wnt inhibitors also leads to impairment of HSC self-renewal (19, 20). The differing actions of PTH on the skeleton and HSCs might then result from differential activation of effector cells. For example, the anabolic actions of PTH appear to be exerted in part through re-activation of bone lining cells into mature osteoblasts (21, 22), and/or via stimulation of terminally differentiated osteocytes (23). In contrast, the hematomodulatory actions of PTH appear to target early-stage osteoblasts. The manipulation of Gsα or PPR within early osteoblastic cells results in striking hematopoietic phenotypes (7, 8), but similar studies within maturing or terminally differentiated osteocytes do not affect B lymphopoiesis (24) or HSC number (25, 26) despite the expected effects on osteoblast numbers. Therefore, the separate anabolic and hematopoietic effects of PTH may be a result of actions in distinct populations of effector cells, which may be differentially activated in different individuals. Alternatively, it may be that those with the greatest anabolic response to PTH may respond with a likewise increase in HSCs within the marrow but are unable to mobilize these HSCs into the circulation. Unfortunately we are unable to test this hypothesis without access to the bone marrow space. Other studies have suggested that bisphosphonates may directly impact the HSC niche (27) and/or inhibit teriparatide’s actions on the HSC niche in mouse models (28). One third of the subjects in the current study had previously used bisphosphonates prior to enrollment, but we did not observe any differences in patterns of HSC response to teriparatide based on previous bisphosphonate use.

Although we observed an early and transient rise in HSCs, daily PTH treatment did not lead to any detectable changes in peripheral numbers of other hematopoietic lineages, including early “transitional” B cells, red blood cells, or platelets. These clinical findings are in contrast with previous animal studies of Gsα manipulation describing arrested B cell development (7) and altered erythrocyte and megakaryocytic development (25). In addition, while mouse models of short-term (14-day) exogenous PTH administration demonstrated increased numbers of circulating lymphocytes and neutrophils (9), we found no change in these cell populations even at our earliest time point of 3 months. These negative findings may be a result of the small sample size of our study, the relative insensitivity of peripheral cell counts, or the physiologic differences between long-term PTH treatment and either short-term treatment or genetic manipulation of the PTH receptor. Alternatively, the difference in hematopoietic response to PTH may reflect inherent differences in the mouse and the human. Finally, our interpretations of the results are limited due to the lack of a control group.

In summary, this study demonstrates that daily teriparatide treatment transiently increases peripheral HSCs in postmenopausal osteoporotic women. This increase may represent a proliferation of marrow HSCs or increased peripheral HSC mobilization. The mechanisms by which PTH increases circulating HSCs are unknown, but could include actions on early osteoblasts. Further studies are required to better define the mechanisms that underlie the effects of PTH on hematopoiesis as well the possible physiologic or pharmacologic consequences of this phenomenon.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Henry Kronenberg for his helpful discussion and critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants AR54741 and OD008466 (to J.Y.W.) and AR61228, and funding support from Amgen Inc. and Eli Lilly Co.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration Number: NCT00926380

Disclosures: E.W.Y. has served as a consultant for Amgen Inc. and Eli Lilly Co.

Authors’ roles: Study design: EWY, BZL, and JYW. Study conduct and data collection: RK, ESS, MD, and FIP. Data analysis and interpretation: EWY, MD, FIP, BZL, and JYW. Drafting manuscript: EWY. Revising manuscript content: All authors. Approving final version of manuscript: All authors. EWY takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nilsson SK, Johnston HM, Coverdale JA. Spatial localization of transplanted hemopoietic stem cells: inferences for the localization of stem cell niches. Blood. 2001 May 15;97(8):2293–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz ÖH, Iwashita T, Yilmaz OH, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM Family Receptors Distinguish Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells and Reveal Endothelial Niches for Stem Cells. Cell. 2005 Jul;121(7):1109–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G, Morrison SJ. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2012 Jan 26;481(7382):457–62. doi: 10.1038/nature10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panaroni C, Wu JY. Interactions between B lymphocytes and the osteoblast lineage in bone marrow. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013 Sep;93(3):261–8. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9753-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visnjic D, Kalajzic Z, Rowe DW, Katavic V, Lorenzo J, Aguila HL. Hematopoiesis is severely altered in mice with an induced osteoblast deficiency. Blood. 2004 May 1;103(9):3258–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu J, Garrett R, Jung Y, Zhang Y, Kim N, Wang J, et al. Osteoblasts support B-lymphocyte commitment and differentiation from hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2007 May 1;109(9):3706–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu JY, Purton LE, Rodda SJ, Chen M, Weinstein LS, McMahon AP, et al. Osteoblastic regulation of B lymphopoiesis is mediated by Gs{alpha}-dependent signaling pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008 Nov 4;105(44):16976–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802898105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003 Oct 23;425(6960):841–6. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunner S, Zaruba MM, Huber B, David R, Vallaster M, Assmann G, et al. Parathyroid hormone effectively induces mobilization of progenitor cells without depletion of bone marrow. Exp Hematol. 2008 Sep;361(9):1157–66. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams GB, Martin RP, Alley IR, Chabner KT, Cohen KS, Calvi LM, et al. Therapeutic targeting of a stem cell niche. Nat Biotechnol. 2007 Feb 25;(2):238–43. doi: 10.1038/nbt1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drake MT, Srinivasan B, Modder UI, Ng AC, Undale AH, Roforth MM, et al. Effects of intermittent parathyroid hormone treatment on osteoprogenitor cells in postmenopausal women. Bone. 2011 Sep;49(3):349–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai JN, Uihlein AV, Lee H, Kumbhani R, Siwila-Sackman E, McKay EA, et al. Teriparatide and denosumab, alone or combined, in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: the DATA study randomised trial. Lancet. 2013 Jul 6;382(9886):50–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60856-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutherland DR. Assessment of peripheral blood stem cell grafts by CD34+ cell enumeration: toward a standardized flow cytometric approach. J Hematother. 1996 Jun;5(3):209–10. doi: 10.1089/scd.1.1996.5.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palanichamy A, Barnard J, Zheng B, Owen T, Quach T, Wei C, et al. Novel human transitional B cell populations revealed by B cell depletion therapy. J Immunol. 2009 May 15;182(10):5982–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballen KK, Shpall EJ, Avigan D, Yeap BY, Fisher DC, McDermott K, et al. Phase I trial of parathyroid hormone to facilitate stem cell mobilization. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007 Jul;13(7):838–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballen K, Mendizabal AM, Cutler C, Politikos I, Jamieson K, Shpall EJ, et al. Phase II trial of parathyroid hormone after double umbilical cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012 Dec;18(12):1851–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellido T, Ali AA, Gubrij I, Plotkin LI, Fu Q, O'Brien CA, et al. Chronic elevation of parathyroid hormone in mice reduces expression of sclerostin by osteocytes: a novel mechanism for hormonal control of osteoblastogenesis. Endocrinology. 2005 Nov;146(11):4577–83. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Brien CA, Plotkin LI, Galli C, Goellner JJ, Gortazar AR, Allen MR, et al. Control of bone mass and remodeling by PTH receptor signaling in osteocytes. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):e2942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaniel C, Sirabella D, Qiu J, Niu X, Lemischka IR, Moore KA. Wnt-inhibitory factor 1 dysregulation of the bone marrow niche exhausts hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2011 Sep 1;118(9):2420–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-305664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleming HE, Janzen V, Lo Celso C, Guo J, Leahy KM, Kronenberg HM, et al. Wnt signaling in the niche enforces hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and is necessary to preserve self-renewal in vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2008 Mar 6;2(3):274–83. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dobnig H, Turner RT. Evidence that intermittent treatment with parathyroid hormone increases bone formation in adult rats by activation of bone lining cells. Endocrinology. 1995 Aug;136(8):3632–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.8.7628403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SW, Pajevic PD, Selig M, Barry KJ, Yang JY, Shin CS, et al. Intermittent parathyroid hormone administration converts quiescent lining cells to active osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2012 Oct;27(10):2075–84. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saini V, Marengi DA, Barry KJ, Fulzele KS, Heiden E, Liu X, et al. Parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide type 1 receptor (PPR) signaling in osteocytes regulates anabolic and catabolic skeletal responses to PTH. J Biol Chem. 2013 Jul 12;288(28):20122–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.441360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fulzele K, Krause DS, Panaroni C, Saini V, Barry KJ, Liu X, et al. Myelopoiesis is regulated by osteocytes through Gsalpha-dependent signaling. Blood. 2013 Feb 7;121(6):930–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-437160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schepers K, Hsiao EC, Garg T, Scott MJ, Passegue E. Activated Gs signaling in osteoblastic cells alters the hematopoietic stem cell niche in mice. Blood. 2012 Oct 25;120(17):3425–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-395418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calvi LM, Bromberg O, Rhee Y, Weber JM, Smith JN, Basil MJ, et al. Osteoblastic expansion induced by parathyroid hormone receptor signaling in murine osteocytes is not sufficient to increase hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2012 Mar 15;119(11):2489–99. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-360933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soki FN, Li X, Berry J, Koh A, Sinder BP, Qian X, et al. The effects of zoledronic acid in the bone and vasculature support of hematopoietic stem cell niches. J Cell Biochem. 2013 Jan;114(1):67–78. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lymperi S, Ersek A, Ferraro F, Dazzi F, Horwood NJ. Inhibition of osteoclast function reduces hematopoietic stem cell numbers in vivo. Blood. 2011 Feb 3;117(5):1540–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.