Abstract

Background and purpose

In traditional radiostereometric analysis (RSA), 1 segment defines both the acetabular shell and the polyethylene liner. However, inserting beads into the polyethylene liner permits employment of the shell and liner as 2 separate segments, enabling distinct analysis of the precision of 3 measurement methods in determining femoral head penetration and shell migration.

Patients and methods

The UmRSA program was used to analyze the double examinations of 51 hips to determine if there was a difference in using the shell-only segment, the liner-only segment, or the shell + liner segment to measure wear and acetabular cup stability. The standard deviation multiplied by the critical value (from a t distribution) established the precision of each method.

Results

Due to the imprecision of the automated edge detection, the shell-only method was least desirable. The shell + liner and liner-only methods had a precision of 0.115 mm and 0.086 mm, respectively, when measuring head penetration. For shell migration, the shell + liner had a precision of 0.108 mm, which was better than the precision of the shell-only method. In both the penetration and migration analyses, the shell + liner condition number was statistically significantly lower and the bead count was significantly higher than for the other methods.

Interpretation

Insertion of beads in the polyethylene improves the precision of femoral head penetration and shell migration measurements. A greater dispersion and number of beads when combining the liner with the shell generated more reliable results in both analyses, by engaging a larger portion of the radiograph.

Radiostereometric analysis (RSA) is a useful and accurate tool for early measurement of femoral head penetration and acetabular cup stability in total hip replacement (THR) (Rohrl et al. 2005, Ryd et al. 2000, Valstar et al. 2005, Glyn-Jones et al. 2008). Indications of implant failure are generally not detectable on plain radiographs in the early postoperative period and clinical symptoms usually occur much later, making RSA a valuable instrument for predicting long-term patient outcomes (Karrholm et al. 1994, Ryd et al. 1995, Pijls et al. 2012). The accuracy and precision of RSA (up to 50 µm) permits studies with smaller patient groups without sacrificing statistical power (Karrholm et al. 1997, Borlin et al. 2002, Karrholm et al. 2006).

Increasing the number of markers subsequently increases the strength and reliability of the RSA migration analysis by using a greater proportion of the radiograph to define a particular segment (Ryd et al. 2000, Valstar et al. 2005). Thus, the polyethylene liner and acetabular shell are often assigned as 1 combined segment in RSA since the running assumption is that there is no motion between the 2 components. Alternatively, if beads are inserted into the liner, the liner and shell can be separated into 2 individual segments. Liner beads allow for the liner segment to be uniquely identified and the shell to be uniquely identified from points automatically assigned to the backshell by the software, after the user has defined the general shape of the shell within the program—thus employing a markerless shell segment that does not require the inclusion of tantalum beads. Additionally, it is possible to compare the liner and shell segments over time to ultimately determine whether in fact the liner is stable within the shell.

Previous phantom RSA studies have indicated that a combined segment might provide optimal precision (Bragdon et al. 2004, Borlin et al. 2006). 1 phantom RSA study demonstrated that wear measured using shell + liner, liner only, or shell only yielded comparable results, and concluded that there was no significant difference in wear measurements between the 3 different methods. However, the shell + liner method used the greatest amount of information in the radiograph, and therefore it was the preferred method (Bragdon et al. 2007). Highly precise and accurate results are essential for these early long-term predictions, but the specialized radiology suite and trained staff that accompany an RSA study are costly (McCalden et al. 2005). In order to minimize costs and the number of patients exposed to new implant technologies before the materials have been vetted with an RSA trial, high levels of precision and accuracy must be obtained (Karrholm et al. 1997, Malchau et al. 2011). The purpose of this in vivo follow-up study was to determine if assigning the shell and liner as 1 combined or 2 individual segments affected the precision of RSA measurements of femoral head penetration into the polyethylene liner and acetabular cup stability in the pelvis.

Patients and methods

47 THR RSA patients (51 hips) from 1 center gave informed consent to participate in a prospective Institutional Review Board approved RSA study. This patient cohort was originally enrolled for the purposes of prospectively monitoring in vivo performance of the new technologies of the Regenerex acetabular shell (Biomet, Warsaw, IN) and the Vitamin E polyethylene liners, which will be reported separately. This cohort consisted of 15 females and 32 males, all of whom had a primary diagnosis of osteoarthritis. The average age at the time of surgery was 59 (26–75) years. The surgeries were performed by 4 arthroplasty surgeons between November 2007 and February 2011. Patients received a Regenerex acetabular cup, an E1 polyethylene liner, a 32-mm cobalt-chromium femoral head, and a Taperloc press-fit femoral stem (all components were from Biomet). Our laboratory previously analyzed the different RSA measurement methods in a phantom model, but this patient cohort presented the opportunity to explore the precision of different RSA measurement methods in vivo by separating the shell and liner segment, as beads were placed in the liners to monitor these implants (Bragdon et al. 2004).

Either 12 or 14 tantalum beads (depending on the size of the acetabular shell) were inserted into the polyethylene liner, and 10 beads on average were inserted into the pelvic bone surrounding the shell. A trained surgical assistant inserted all tantalum beads into the liner in the operating room using a customized jig. Patients returned for RSA follow-up postoperatively up to 6 weeks (average 15 (0–43) days after surgery), at 6 months, and 1, 2, 3, and 5 years after surgery. A uniplanar calibration cage (cage 43) was positioned beneath the patient in supine position such that the long axis of the femur was parallel to the y-axis and the femoral stem, acetabular cup, and pelvic beads were within the reference points on the cage. 2 digital radiographs were taken simultaneously with 2 ceiling-mounted X-ray tubes at convergent 40-degree angles and the cage was used as a reference for all subsequent digital image comparisons. As a result, a 3D reconstruction of the segments, defined by the tantalum beads in each anatomical area, was created.

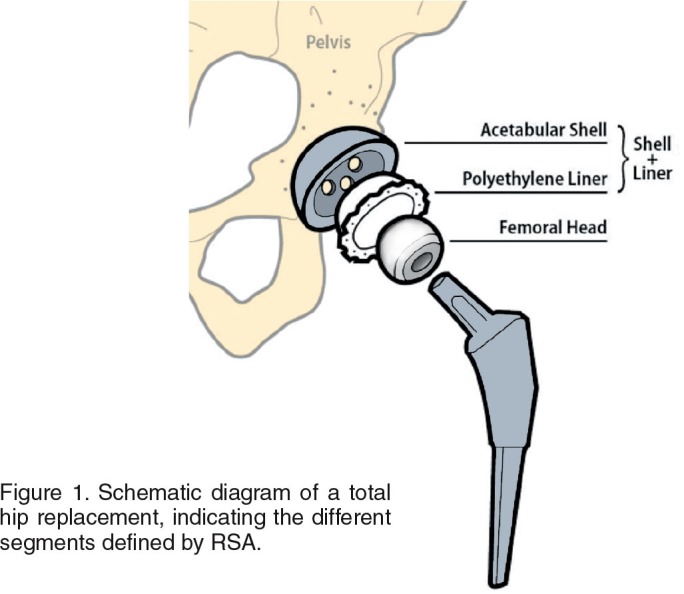

There are several ways to measure an RSA film pair, depending on where beads have been implanted. In this study, we investigated each measurement method (Figure 1). There were 5 component and anatomic segments defined for this study: (1) The head was measured by assigning a sphere using automated edge detection in order to determine its center. (2) Up to 9 beads were labeled in the polyethylene liner to define the liner segment, and no film pairs had less than 4 beads visible in both foci. The UmRSA software allows a maximum of 9 beads per segment; for example, the polyethylene segment was segment 23 and the beads labled1 through 9 (beads 231 to 239). When more than 9 beads were visible in the liner, those remaining were assigned to an unused segment 24. The beads assigned to segment 23 were optimized for their visualization in both foci and those relegated to segment 24 were left over because they were not visualized in both foci. (3) For the shell-only method, 5 points were assigned by the program to the acetabular backshell using edge detection: one at the north pole, one at the south pole, one anterior point, one posterior point, and the center of the sphere (Borlin et al. 2006). (4) The shell + liner segment was defined by up to 6 beads labeled in the polyethylene liner and 3 points were assigned to the shell using edge detection because only 9 points can define any one segment. (5) The pelvic segment was defined by up to 9 beads labeled in the pelvic bone and labeled as segment 11 (beads 111 to 119) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a total hip replacement, indicating the different segments defined by RSA.

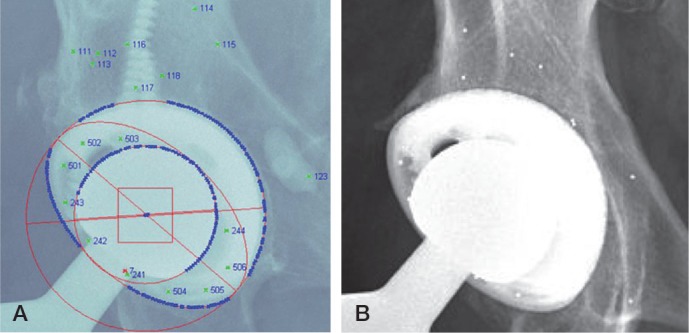

Figure 2.

A. Image of a total hip replacement with RSA markings. The acetabular shell and femoral head are defined by edge detection (ellipses), the marked tantalum beads in the pelvic bone are numbered 111–118, and the polyethylene liner beads are numbered 231–236 and 241–243. B. AP hip image showing the unmarked tantalum beads in the pelvis and liner.

RSA radiographs were analyzed with UmRSA 6.0 software (RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden). Both point motion and segment motion were investigated. Point motion measured the change in a single point with respect to a defined segment. Segment motion measured the change in 1 segment relative to a reference segment that was assumed to be stable. Polyethylene wear was measured using point motion of the center of the femoral head with respect to 3 segments: (1) the liner-only segment, (2) the shell-only segment, and (3) the shell + liner segment. Cup stability was measured by segment motion comparing the stable pelvic segment to (1) the liner segment, (2) the shell-only segment, and (3) the shell + liner segment. Rotation of the acetabular shell using the shell-only method was not reported because the 3D rotational motion of the shell alone cannot be measured due to the 2D technique of edge detection. Liner stability within the shell was reported in 2 ways: (1) the liner segment compared to the shell-only segment, and (2) the liner compared to the pelvis segment.

2 sets of RSA images (double examinations) were captured at least once for each patient at the same visit, to establish the precision of each measurement method. The precision was defined by multiplying the standard deviation by the appropriate critical value (t), based on a t distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of observations, n, minus 1. The precision interval was defined by the mean (with SD) multiplied by the critical value. Each RSA measurement method had a slightly varied number of observations, due to error limits set for the analyses such as mean errors or condition numbers that were too high, or there were not enough beads to define a particular segment. Thus, the critical value used to calculate precision was not consistent for all methods.

If a patient had several double examinations, the set of double examinations used for that patient was determined by the best positioning of the acetabular shell and pelvis beads within the calibration cage. If one set of double examinations was not obviously superior to another, the determination was then based on the greatest bead count in each analysis, in order to use as much information defining each segment as possible, then by the lowest condition number, and then by lowest mean error. The condition number determined the quality of dispersion of the tantalum markers within each segment. The mean error represents the stability of the tantalum beads from one time point to the next, and was calculated with an algorithm that determined the difference in the respective distances of the beads over time. Thus, for both the mean error and the condition number, low numbers were most desirable. The same double examination set was used for all analysis methods for each patient. This study adhered to the guidelines for mean error and condition number tolerances for RSA studies, which were 0.25 and 110, respectively (Valstar et al. 2005).

Statistics

The Wilcoxon paired signed ranks test (SPSS version 17.0) was used to determine differences in the condition numbers and bead counts among the 3 measurement methods for polyethylene wear and between the 2 methods for acetabular cup stability. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Ethics and registration

The enrollment of these patients for the purpose of monitoring wear and cup and stem stability using RSA was approved by the Institutional Review Board. This study has also been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number: NCT00551967).

Results

Usable double examinations were obtained for 50 of the 51 hips. The precision of the head penetration measurements was 0.086 mm for the liner-only method, 0.257 mm for the shell-only method, and 0.115 mm for the shell + liner method in the y-axis. In all 3 axes, the shell-only method was the least precise for measurement of femoral head penetration, and in the x- and z-axes, the shell + liner method showed superior precision (Table 1, see Supplementary data). The median bead count for the liner-only segment was 5 and the median condition number was 52; for the shell-only segment, the values were 5 and 25, respectively, and for the shell + liner segment they were 8 and 23. The shell + liner analysis had a significantly better median bead count and condition than both the liner-only and shell-only analyses (both p < 0.001).

The precision, median condition number, and median bead count determined that the shell + liner method was the most desirable method for measuring superior cup translation, as the precision for this method along the y-axis was 0.108 mm. For the shell + liner method, the median bead/point count was 8 and the median condition number was 24. The liner-only method showed a precision of 0.105 mm, but yielded a poorer median bead count of 5 and a higher median condition number of 52. The shell-only analysis resulted in the worst precision across all 3 axes, with a median point count of 5 and median condition number of 26 (Table 2). For acetabular cup rotation, the shell + liner method showed superior precision over the liner-only method, and in all 3 axes (Table 3, see Supplementary data). Again, the condition number was lower and the bead count was higher in the shell + liner analysis than in the liner-only and the shell-only analyses (p < 0.001 for both comparisons).

Table 2.

The mean (SD) precision (mm), and precision interval (all calculated from double examinations) in measuring acetabular cup translation in the x-, y-, and z-planes. The precision is defined by the SD × critical value (t) and the precision interval is defined by the mean (SD) × t

| Method / Plane | Mean (SD) | Precision | Precision interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liner (n = 44) | |||

| x | −0.002 (0.079) | 0.161 | −0.163 to 0.159 |

| y | −0.004 (0.520) | 0.105 | −0.109 to 0.102 |

| z | −0.021 (0.227) | 0.457 | −0.478 to 0.436 |

| Shell (n = 47) | |||

| x | −0.011 (0.148) | 0.298 | −0.309 to 0.287 |

| y | 0.024 (0.138) | 0.278 | −0.255 to 0.302 |

| z | −0.023 (0.311) | 0.626 | −0.649 to 0.603 |

| Shell + liner (n = 45) | |||

| x | −0.007 (0.091) | 0.184 | −0.191 to 0.177 |

| y | 0.003 (0.054) | 0.108 | −0.105 to 0.111 |

| z | −0.023 (0.197) | 0.397 | −0.421 to 0.374 |

The true motion of the liner with respect to the shell, and of the liner with respect to the pelvis was measured for the purpose of ensuring that the liners were not moving within the shells. The mean (SD) superior translation (y-axis) of the liner (backside wear), compared to the shell, was −0.039 (0.16) mm, which was within the error of detection for this method as determined by the precision interval, calculated from the double examinations (Table 4). When comparing the shell to the pelvis, the shell translated 0.190 (0.20) mm in the superior direction, which was again within the confines of the error of detection, and thus not considered true motion. Both translation and rotation of the liner with respect to the pelvis were within the precision interval; thus, no true motion was detected (Table 5). We therefore conclude that if the liners were moving, it was at a magnitude that was undetectable. Since all motion was within the precision interval, combining the shell and liner into one segment is justified—as these 2 segments individually do not move with respect to each another.

Table 4.

Mean (SD) translation (mm) of the polyethylene liner, derived from 2 measurement methods, and the precision of the measurements as defined by the mean (SD) × t

| Segments / Plane | Mean liner motion (SD) | Precision | Precision interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liner to shell (n = 45) | |||

| x | −0.025 (0.147) | 0.211 | −0.221 to 0.201 |

| y | −0.039 (0.160) | 0.193 | −0.187 to 0.199 |

| z | −0.029 (0.428) | 0.654 | −0.690 to 0.619 |

| Liner to pelvis (n = 44) | |||

| x | −0.010 (0.211) | 0.161 | −0.163 to 0.159 |

| y | 0.101 (0.174) | 0.105 | −0.109 to 0.102 |

| z | −0.017 (0.287) | 0.457 | −0.478 to 0.436 |

Table 5.

Mean (SD) rotation (°) of the polyethylene liner, derived from 2 measurement methods, and the precision of the measurements as defined by the mean (SD) × t

| Segments / Plane | Mean liner motion (SD) | Precision | Precision interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liner to shell (n = 45) | |||

| x | –0.370 (1.607) | 1.441 | –1.297 to 1.585 |

| y | 0.022 (2.128) | 1.894 | –1.794 to 1.995 |

| z | 0.013 (0.814) | 0.775 | –0.752 to 0.797 |

| Liner to pelvis (n = 44) | |||

| x | –0.060 (0.420) | 0.826 | –0.813 to 0.838 |

| y | 0.010 (0.484) | 1.067 | –1.163 to 0.972 |

| z | 0.038 (0.390) | 0.343 | –0.332 to 0.353 |

Discussion

RSA is a reliable tool for assessment of micromotion early in the postoperative period, and the precision of this tool can vary depending on bead placement and the type of analysis performed. Our results indicate that the use of beads in the polyethylene liner led to an improvement in the precision of wear and acetabular cup migration measurements over the shell-only method. Putting beads in the liner permitted up to 9 points to define the cup segment, rather than using the shell or liner alone (with an of average of 5 beads). Due to the software’s algorithm of automated edge detection to define the shell, the program only allows for a maximum of 5 points for this segment, which is a limitation of using the shell-only method in the UmRSA software, since less information from the radiograph is used. Although 12–14 beads were implanted into the liner, ultimately 7 or fewer beads were visible in the radiograph due to obstruction by the femoral head and neck. Since the shell + liner analysis considered points in the liner and shell (not just each segment individually), more of the information in the radiograph was used—which increased the precision of the analysis, as evidenced by improved rotational precision of the cup and the statistically significantly improved condition number and bead counts for this method compared to the other methods (Ryd et al. 2000, Borlin et al. 2006). Thus, adding beads to the liner increased the precision and gave more reliable RSA results.

The precision, low condition numbers, and higher bead counts of the shell + liner technique confirmed that this method used a greater dispersion of measurement points and more information from the radiograph than the liner-only and shell-only methods. Traditionally, RSA migration comparisons are selected based first upon the highest bead count followed by the lowest condition number, and then by the lowest mean error of any given comparison (Valstar et al. 2005). These criteria define which migration comparisons are the most reliable. Because the shell + liner technique showed improved precision and consistently used more measurement points with a greater dispersion within the joint (a lower condition number), it was the most desirable method for measurement of polyethylene wear (Soderkvist and Wedin 1993).

The precision of the liner-only and the shell + liner methods was similar in cup translation analyses, and it was better than that for the shell-only method, indicating that the addition of beads to the liner improved the ability to define the acetabular cup segment. Additionally, incorporation of the shell points into the measurement of the acetabular cup segment improved the rotational precision and improved both the bead count and the condition number when using the shell + liner segment instead of the liner-only segment. Since there was no discernible migration of the polyethylene liner within the shell, we feel confident in combining the shell and liner to form one segment (shell + liner).

While the shell-only method was inherently limited by the software using only 5 points assigned by computer, the edge detection of these shells may have been further disadvantaged by the porous metal surface of the Regenerex shell. The added porosity projected a less well defined edge encompassing the periphery of the shell in the radiographic image. Perhaps the shell-only method would have been more precise if the shells had not been porous-coated. The addition of a second patient group with a different porous coating on the shells could provide more information about the program’s ability to identify the shell segment using edge detection. Even if the precision were to improve in shells with a different coating, the bead count and probably the condition number would still not be as ideal as the shell + liner method. It should be noted that all shells have some type of coating, so perhaps using the shell-only method to define the shell segment in the UmRSA system is not ideal due to the inability of the program to determine the solid edge of the shells. The results of our study call into question the use of model-based RSA systems in conjunction with this particular shell, especially since new porous-coated acetabular component designs are being increasingly used clinically.

Adding beads to the polyethylene and peripheral bone of a patient can be done intraoperatively with approximately 5 minutes of extra time, since all the components necessary for doing so will already be available. RSA studies have been conducted in Europe for several decades, and no negative clinical effects from the tantalum beads have been reported (Karrholm et al. 1997). The beads in the polyethylene liner can be inserted simultaneously by the surgical assistant, which will require extra staff time. Ideally, the beads can be inserted by the manufacturer, which has occurred in the past for study-specific components (Valstar et al. 2005). These extra data points increase the precision and most likely the accuracy of measurement of polyethylene wear and acetabular cup migration since the shell + liner can be combined into one segment, with many more points than the shell or liner segments alone (due to obstruction by the femoral head and neck). Using a combined segment also provides an easy alternative to marking the acetabular cup with tantalum beads, which is time-consuming, expensive, and difficult to achieve because of manufacturers’ preponderant opposition to altering their components (Valstar et al. 1997, Kaptein et al. 2004). The liner beads also allow measurement of cup rotation of the shell + liner segment, which is not possible when using the shell segment alone.

In summary, our study justifies adding beads into the polyethylene liner because doing so increases the precision of wear and migration (translation and rotation) measurements. As the prediction of implant survivorship in the early postoperative period relies heavily on RSA, it is crucial to use the most precise system to monitor these implants (McCalden et al. 2005, Karrholm et al. 2006, Malchau et al. 2011). In order to achieve maximum benefit from studies on small patient cohorts, a very precise and reliable method of migration detection is necessary to ensure full confidence in the results, and the shell + liner method meets that standard.

Acknowledgments

AN wrote the manuscript and performed the data analysis and the statistical analysis. KR and HP performed statistical analysis and edited the manuscript. HM contributed to analysis of the data and edited the manuscript. MG performed data analysis, assisted with the statistical analysis, and edited the manuscript.

We thank Janet Dorrwachter for her work in enrolling and following the patients in this study. We also thank Tobias Haak for his help with the early analysis of data. We are grateful to Kip Lyall for preparation of the schematic diagram (Figure 1). Funding for this study was provided by the Harris Orthopaedic Laboratory.

No competing interests declared.

Supplementary data

Tables 1 and 3 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 7515.

References

- Borlin N, Thien T, Karrholm J. The precision of radiostereometric measurements. Manual vs. digital measurements . J Biomech. 2002;35(1):69–79. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlin N, Rohrl SM, Bragdon CR. RSA wear measurements with or without markers in total hip arthroplasty . J Biomech. 2006;39(9):1641–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragdon CR, Estok DM, Malchau H, Karrholm J, Yuan X, Bourne R, Veldhoven J, Harris WH. Comparison of two digital radiostereometric analysis methods in the determination of femoral head penetration in a total hip replacement phantom . J Orthop Res. 2004;22(3):659–64. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragdon CR, Greene ME, Freiberg AA, Harris WH, Malchau H. Radiostereometric analysis comparison of wear of highly cross-linked polyethylene against 36- vs 28-mm femoral heads . J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 Suppl 2):125–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glyn-Jones S, McLardy-Smith P, Gill HS, Murray DW. The creep and wear of highly cross-linked polyethylene: a three-year randomised, controlled trial using radiostereometric analysis . J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(5):556–61. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B5.20545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein BL, Valstar ER, Stoel BC, Rozing PM, Reiber JH. Evaluation of three pose estimation algorithms for model-based roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis . Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2004;218(5):231–8. doi: 10.1243/0954411041561036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrholm J, Borssen B, Lowenhielm G, Snorrason F. Does early micromotion of femoral stem prostheses matter? 4-7-year stereoradiographic follow-up of 84 cemented prostheses . J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(6):912–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrholm J, Herberts P, Hultmark P, Malchau H, Nivbrant B, Thanner J. Radiostereometry of hip prostheses. Review of methodology and clinical results . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;344:94–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrholm J, Gill RH, Valstar ER. The history and future of radiostereometric analysis . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;448:10–21. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000224001.95141.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchau H, Bragdon CR, Muratoglu OK. The stepwise introduction of innovation into orthopedic surgery: the next level of dilemmas . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(6):825–31. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCalden RW, Naudie DD, Yuan X, Bourne RB. Radiographic methods for the assessment of polyethylene wear after total hip arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(10):2323–34. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijls BG, Nieuwenhuijse MJ, Fiocco M, Plevier JW, Middeldorp S, Nelissen RG, Valstar ER. Early proximal migration of cups is associated with late revision in THA: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 RSA studies and 49 survivalstudies . Acta Orthop. 2012;83(6):583–91. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.745353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrl S, Nivbrant B, Mingguo L, Hewitt B. In vivo wear and migration of highly cross-linked polyethylene cups a radiostereometry analysis study . J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(5):409–13. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryd L, Albrektsson BE, Carlsson L, Dansgard F, Herberts P, Lindstrand A, Regner L, Toksvig-Larsen S. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee prostheses . J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(3):377–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryd L, Yuan X, Lofgren H. Methods for determining the accuracy of radiostereometric analysis (RSA) . Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(5):403–8. doi: 10.1080/000164700317393420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderkvist I, Wedin PA. Determining the movements of the skeleton using well-configured markers . J Biomech. 1993;26(12):1473–7. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(93)90098-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valstar ER, Spoor CW, Nelissen RG, Rozing PM. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis of metal-backed hemispherical cups without attached markers . J Orthop Res. 1997;15(6):869–73. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valstar ER, Gill R, Ryd L, Flivik G, Borlin N, Karrholm J. Guidelines for standardization of radiostereometry (RSA) of implants . Acta Orthop. 2005;76(5):563–72. doi: 10.1080/17453670510041574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.