Occupational therapy has the philosophical underpinnings to provide expanded and more effective client-centered care that emphasizes the active engagement of the client and recognizes the greater contexts of his or her life.

MeSH TERMS: health reform, nondirective therapy, occupational therapy, patient-centered care, patient outcome assessment

Abstract

Health reform promotes the delivery of patient-centered care. Occupational therapy’s rich history of client-centered theory and practice provides an opportunity for the profession to participate in the evolving discussion about how best to provide care that is truly patient centered. However, the growing emphasis on patient-centered care also poses challenges to occupational therapy’s perspectives on client-centered care. We compare the conceptualizations of client-centered and patient-centered care and describe the current state of measurement of client-centered and patient-centered care. We then discuss implications for occupational therapy’s research agenda, practice, and education within the context of patient-centered care, and propose next steps for the profession.

Much of client-centered theory in occupational therapy mirrors principles of the wider patient-centered movement in health care. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA; Pub. L. 111–148) emphasizes patient centeredness as both an outcome in and of itself and as a means to improve health outcomes (Millenson & Macri, 2012). To this end, occupational therapy has the philosophical underpinnings to provide expanded and more effective client-centered care that emphasizes the active engagement of the client and recognizes the greater contexts of his or her life. Yet, the emphasis on patient centeredness also poses challenges to traditional thinking in occupational therapy around client centeredness that must be addressed for the profession to keep pace with health reform.

In this article, we describe client centeredness as most often defined in occupational therapy and patient centeredness within the broader health care system, and illustrate similarities and differences between them. In addition, we discuss how occupational therapy can help inform the evolving conceptualization of patient centeredness by sharing perspectives from a rich foundation of client-centered theory and practice, including measurement of client-centered care. We then outline implications for occupational therapy research, practice, and education.

Origins of Client-Centered and Patient-Centered Care

Occupational therapy has long considered client centeredness a key component of practice. Aspects of client centeredness, such as acknowledging the importance of the client’s perspectives in treatment planning, have been present in occupational therapy values since the very beginning of the profession (Bing, 1981). Eventually, the profession worked to formally define client centeredness and describe what it means to provide client-centered therapy (Kyler, 2008; Law, Baptiste, & Mills, 1995; Law & Mills, 1998; Townsend, Brintnell, & Staisey, 1990), with the earliest formal reference to client-centered practice appearing in 1983 (Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists [CAOT] & Department of National Health and Welfare, 1983). The formalization of the working concept of client centeredness, led by Canadian occupational therapists, marked the beginning of a growing literature on client-centered theory and practice.

Similarly, the roots of the modern patient-centered care movement can be traced back several decades to initiatives involving care for children with special needs, early medical homes, and patient advocacy in the 1960s and 1970s (de Silva, 2014; National Quality Forum [NQF], 2014). The patient-centered care movement gained prominence when the Institute of Medicine (IOM; 2001) cited patient-centered care as one of six aims in its seminal report on improving health care quality, and momentum has continued to build since then.

Health Reform and Patient Centeredness

Patient centeredness was already part of the national conversation on improving the quality of health care when the ACA was signed into law in 2010, so it is not surprising that the ACA contains multiple elements directly related to patient-centered care. Indeed, the text of the ACA mentions the term patient-centered several dozen times and includes variations on core concepts for building a more patient-centered system. The overall national strategy to improve health care as outlined by the ACA includes improving patient centeredness as a key priority. Measurement of patient centeredness is described as a critical outcome for quality of care, and quality improvement approaches, incentive programs, and payment reform initiatives are all tied to patient-centered measures that are either in use or to be developed.

As implied by its name, the patient-centered medical home, one model of primary care promoted by the ACA for payment and practice reform, is defined by inclusion of many of the core components of patient centeredness. In addition, the ACA specifies that training of all health professionals should emphasize patient-centered care. The ACA also created the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), which has a national research agenda focused on patient-centered outcomes and has been funding projects related to this agenda since 2012 (PCORI, 2012). Because patient centeredness is a crucial focus of the ACA in particular and of health care transformation more generally as a dimension of the patient experience component of the Triple Aim (Berwick, Nolan, & Whittington, 2008), occupational therapy practitioners need to be cognizant of how the profession’s concepts of client centeredness dovetail with and differ from patient centeredness.

Comparing Client-Centered and Patient-Centered Care

Occupational therapy primarily uses the term client rather than patient to identify recipients of service (American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2014; CAOT, 2013), but it is recognized that terminology may vary by practice setting, such as “residents in housing, patients in medical settings, or students in educational settings” (CAOT, 2013, p. 116). Despite some controversy concerning the ethical, legal, and practical implications when the use of client versus patient gained traction in the 1980s (Reilly, 1984; Sharrott & Yerxa, 1985), use of client implies active participation and may serve to reinforce a more collaborative therapeutic process (CAOT, 2013; Herzberg, 1990).

One of the most widely cited definitions of client-centered practice in occupational therapy is from the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists which described client-centered practice as “collaborative approaches aimed at enabling occupation with clients who may be individuals, groups, agencies, governments, corporations or others” that requires “occupational therapists demonstrate respect for clients, involve clients in decision-making, advocate with and for clients in meeting their needs, and otherwise recognize clients’ experience and knowledge” (CAOT, 1997, p. 49; CAOT, 2002, p. 180). Multiple concepts are embedded in this definition, including respect, collaboration and shared decision making, and valuing of the client’s contributions.

Sumsion and Law’s (2006) literature review of the conceptualization of client centeredness in occupational therapy confirmed the key concepts incorporated in the CAOT definition but also highlighted the role of open communication between practitioner and client and the importance of giving hope as core elements of client centeredness. Moreover, this literature review added nuance to the concept of shared decision making by stressing that the transfer of power to the client is what enables an equal partnership between the client and practitioner.

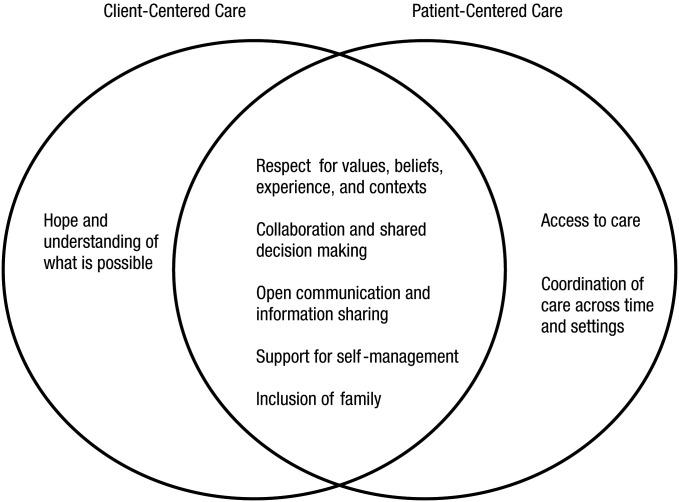

AOTA’s (2014) Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process (3rd ed.) refers to several of the same concepts of client-centered care. The Framework includes values, beliefs, and spirituality as important client factors and recognizes that cultural and temporal contexts and the social environment influence participation. The Framework also identifies collaboration between practitioner and client as central to the occupational therapy process and underscores the importance of understanding the goals of the client in planning intervention. Furthermore, the Framework recognizes family members and caregivers as clients in the occupational therapy process. Taken together, the CAOT (2013) definition, Sumsion and Law’s (2006) review, and the Framework suggest that occupational therapy’s view of client-centered care contains the core concepts of respect for a client’s values, beliefs, experience, and contexts that influence participation; active collaboration throughout the occupational therapy process, with the balance of power weighted toward the client; open communication; inclusion of family; support for participation in care and self-management; and the provision of hope and possibility.

Patient-centered care descriptions contain many similar views. Multiple definitions of patient-centered care exist in the literature, and the core concepts embedded in these definitions are often comparable to one another. The NQF, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that reviews and endorses quality measures, recently tasked a work group with defining patient-centered care as a precursor to understanding measurement of the delivery of patient-centered care. Drawing on foundational work from leaders in the patient-centered care movement, including the IOM, the Picker Institute, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, the Commonwealth Fund, and Planetree, the NQF defined patient-centered care as “an approach to the planning and delivery of care across settings and time that is centered around collaborative partnerships among individuals, their defined family, and providers of care” and that “supports health and well-being by being consistent with, respectful of, and responsive to an individual’s priorities, goals, needs, and values” (NQF, 2014, p. 2).

The core components described by NQF as vital to patient-centered care include respect, inclusion of family as defined by the patient, information sharing and communication, shared decision making, individualized care that is coordinated across settings and time, support for self-management, and access to care that is convenient and in the form preferred by the patient. Although a universally accepted or endorsed definition of patient-centered care does not exist, these core components align with prior seminal work on patient-centered care (Cronin, 2004; de Silva, 2014; NQF, 2014).

Figure 1 depicts the similarities and differences between the core concepts of occupational therapy’s perspective of client-centered care and patient-centered care in health care more broadly. Both perspectives appreciate the multidimensional nature of providing this type of care. A general convergence of concepts exists despite some differences in terminology, suggesting a great deal of overlap between client-centered and patient-centered care. However, the areas in which the concepts diverge provide a chance for occupational therapy to examine potential gaps in its view of client centeredness and offer opportunities for the profession to contribute to refining the health system’s conceptualization of patient-centered care.

Figure 1.

Intersection between core components of client-centered care and patient-centered care.

Care coordination and team-based care underlie many proposed directions for revamping the health care system and represent an opportunity for occupational therapy (Moyers & Metzler, 2014). Occupational therapy’s concepts of client-centered care do not currently emphasize collaboration and coordination of care beyond the practitioner–client dyad. As it stands, occupational therapy’s view of client centeredness, although highly aware of the rich contexts and environments of the client, does not incorporate the context of the wider health care team. An explicit recognition of how occupational therapy interacts with others involved in care (e.g., physicians, nurses, physician extenders, physical therapists, speech–language pathologists, teachers, employers, social workers) is necessary to facilitate better collaboration and thus more coordinated care. Coordination may be particularly important for transitions between rehabilitation and the community (Cott, 2004).

Further, client-centered care also does not clearly acknowledge access to care as a core component; access includes the ability to seek and receive care according to patient needs and preferences. Although barriers to access to care are implied to an extent within occupational therapy’s view of the greater contexts and environments that affect a client, an explicit appreciation is warranted that occupational therapy services need to be available when and how a client requires them for care to be truly client centered (Gupta & Taff, 2015; Pitonyak, Mroz, & Fogelberg, 2015).

One element that client centeredness may add to patient-centered care is the notion of hope and belief in possibilities; occupational therapy’s concept of understanding what is possible is not an explicit part of patient-centered care. As the emphasis on shared decision making in health care grows, it will be essential for providers to be equipped with the skills and understanding to address hope as it influences health and well-being. Occupational therapy can provide insight concerning how to acknowledge and address the hopes of patients and their loved ones because this approach is frequently part of occupational therapy service delivery (Spencer, Davidson, & White, 1997).

For example, in rehabilitation, patients often have to reconcile the incompatibility of their physical or mental capacity with their perceptions of themselves in the past or in the future (Wood, Connelly, & Maly, 2010). As they explore new roles and possibilities, hope may promote optimum achievement. Having hope during rehabilitation has been shown to increase participation in life roles and life satisfaction after discharge (Berges, Seale, & Ostir, 2012; Kortte, Gilbert, Gorman, & Wegener, 2010; Kortte, Stevenson, Hosey, Castillo, & Wegener, 2012; Popovich, Fox, & Burns, 2003). Rehabilitation clinicians can aim to work collaboratively with the patient and caregiver to facilitate care decisions by providing them with the knowledge and strategies needed to maintain hope and achieve desired goals.

The concept of hope is central to habilitative and primary care services as well. Occupational therapy’s method of communicating and supporting hope could inform emerging conversations about how to recognize and support realistic hope within chronic illness management (Hudon et al., 2012). As occupational therapy and the health care system focus on health in a more holistic, long-term way, hope may become a critical health concept (Mattingly, 2010) and thus may provide an opening for occupational therapy practitioners to share how their methods build on and are steeped in hope for “living life to its fullest.”

Measuring Client-Centered and Patient-Centered Care

Measurement of patient outcomes and experience is playing an increasing role in health care transformation efforts. Measurement is both a major theme of the ACA and the focus of the IMPACT Act of 2014 (Pub. L. 113–185), which mandates reporting of quality data by all postacute care settings. Leland, Crum, Phipps, Roberts, and Gage (2015) described a useful framework for quality measurement and value-based care to help position occupational therapy for the future. Because patient centeredness is now viewed as a critical component of quality and value in health care (ACA, 2010; Berwick et al., 2008; IOM, 2001), it is useful to look at additional detail on the current status of measurement of client-centered care and patient-centered care and on opportunities for future work in this area.

NQF endorsement is widely viewed as the gold standard in health care quality measurement; for example, the IMPACT Act requires that measures be NQF endorsed when possible. The NQF evaluates measures of patient-centered care that include patient-reported experience with care, patient-reported or clinician-assessed functional status and health-related quality of life, communication, cultural awareness, and other miscellaneous processes and outcomes related to patient centeredness (NQF, 2015). The Consumer Assessment of Health Providers and Systems family of surveys from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality are one example of NQF-endorsed measures of patient experience (www.cahps.ahrq.gov). Setting-specific measures of functional status that are already in use for public reporting by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have been recommended for NQF endorsement (NQF, 2015).

In addition to measures used for research, public reporting, and payments, quality improvement tools exist to help facilities, departments, and providers assess their current status in providing patient-centered care and create prioritized action plans to increase patient centeredness. For example, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care provides multiple resources and practical tips for providing patient-centered care (http://www.ipfcc.org/tools/downloads-tools.html), and Planetree offers a practical improvement guide for hospitals (http://planetree.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Patient-Centered-Care-Improvement-Guide-10.10.08.pdf).

Because no universal definition of client-centered care or patient-centered care exists, it is not surprising that approaches to measurement vary. A recent review of the measurement of patient-centered care examined both what is generally measured and how it is measured; findings suggest that despite a proliferation of tools to measure patient-centered care through surveys of patients and clinicians and clinical observations, which tools perform best is not clear, and a single tool is unlikely to capture all aspects of patient-centered care (de Silva, 2014). Even if a universal definition existed, operationalizing all aspects of the core components into measureable behaviors that reflect both clinical practice and patient experience remains a challenge (de Silva, 2014; Epstein, Fiscella, Lesser, & Stange, 2010; NQF, 2015; Stiefel & Nolan, 2012). Furthermore, development is needed of measures that address non-English-speaking patients, that are appropriate for care settings outside of hospitals and ambulatory care, and that adequately track change over time (de Silva, 2014; Hudon et al., 2012; NQF, 2014). Reconciling care that results in positive patient satisfaction with negative clinical outcomes is also a limitation of some patient-reported experience measures (Epstein & Street, 2011). Involving patients in measure development is one strategy to address some of these issues (de Silva, 2014).

Because many of the core concepts of patient-centered care and client-centered care overlap, some measures of patient-centered care may be appropriate for measuring client-centered care. Occupational therapy also has measures unique to the profession that address aspects of client-centered care; the best known is the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM; Law et al., 1990), which was designed with client-centered practice in mind and is used both as a tool for collaborative goal setting for occupational therapy and as an outcome measure. The COPM has been shown to be reliable and valid for research and practice with many client populations (Carswell et al., 2004; Dedding, Cardol, Eyssen, Dekker, & Beelen, 2004; Enemark Larsen & Carlsson, 2012; Eyssen et al., 2011). Other assessments, such as the Client-Centered Rehabilitation Questionnaire (Cott, Teare, McGilton, & Lineker, 2006) and the Client-Centredness of Goal Setting (Doig, Prescott, Fleming, Cornwell, & Kuipers, 2015) scale, were designed specifically to address one or more aspects of client-centered care. Occupational therapy has a responsibility to consider appropriate measures of client centeredness for research and practice but also the opportunity to contribute to development and evaluation of measures of patient-centered care based on prior work in this area.

Implications for Research, Practice, and Education

For occupational therapy to demonstrate its value within the evolving health care system, the profession must consider how the ever-increasing focus on patient-centered care may shape research, practice, and education. Occupational therapy should continue to include client-centered care as part of its overall research agenda. Refinement of the definitions of client-centered care and core concepts is necessary (Kyler, 2008). Careful consideration should be given to the convergence and divergence in concepts and terminology between client-centered and patient-centered care so that occupational therapy can share its perspectives and remain relevant in the ongoing conversations around patient centeredness in health care.

A refined definition and delineation of core concepts grounded in occupational therapy theory will also enable further use of existing reliable and valid measures of client-centered and patient-centered care and spur development of new measures as needed. Additionally, a clearer understanding of how core concepts of client-centered care are operationalized in practice will allow for robust study of the translation of client-centered care principles to practice, a critical link that has not been well established in the literature to date (Gupta & Taff, 2015; Hammell, 2013; Kjellberg, Kåhlin, Haglund, & Taylor, 2012; Kyler, 2008; Maitra & Erway, 2006; Rebeiro, 2000). This translation of theory to practice will also contribute to the nascent, inconclusive literature on whether patient-centered care actually leads to better outcomes for patients in areas beyond the patient experience (Fredericks, Lapum, & Hui, 2015; Rathert, Wyrwich, & Boren, 2013).

Occupational therapy researchers are also positioned to develop or collaborate on research proposals that support the mission of PCORI and include the experience of patients as a vital component. Occupational therapy’s relative expertise in patient-centered care concepts, along with PCORI’s history of funding projects related to rehabilitation and populations with which occupational therapy practitioners work, make PCORI a potential funding source for projects within this scope. Further, occupational therapy practitioners’ expertise in collaborating with clients throughout the direct care process may be useful in involving patients as key stakeholders throughout the research process, which is a necessary element for PCORI funding.

While the profession continues to develop the research base on client-centered theory and practice, implications for occupational therapy practice in both traditional and emerging practice settings must also be considered within the context of patient-centered care. Because occupational therapy is already a key part of the rehabilitation team in acute and postacute care, the profession has an obligation to contribute to implementation of patient-centered care processes in these settings. Indeed, occupational therapy practitioners can provide keen insights on interdisciplinary quality improvement teams tasked with addressing patient-centered care because they have training and practice experience with several of the core components. Occupational therapy practitioners need to be aware, however, that different professions may value or emphasize different core components, which may create challenges for translation into practice (Kitson, Marshall, Bassett, & Zeitz, 2013).

Occupational therapy must take the value it places on client involvement into emerging areas of practice such as primary care, prevention, and other non-traditional rehabilitation settings. The promotion of primary care in the ACA creates opportunities and challenges for occupational therapy’s involvement in primary care (Metzler, Hartmann, & Lowenthal, 2012). For occupational therapy to capitalize on the elevation of primary care’s role in health system and payment reform models, including patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations, the profession needs to align client-centered care with the principles of patient-centered care that have been associated with chronic disease management (Hudon, Fortin, Haggerty, Lambert, & Poitras, 2011; Hudon et al., 2012; Wagner et al., 2005).

As health and wellness programming for primary and secondary prevention at the population level also becomes more prominent because of these models of care, occupational therapy has the potential to contribute through its expertise on habits, roles, and routines. Although the ACA addresses the importance of patient-centered care and the health of populations, core components of both patient centeredness and client centeredness are heavily focused at the individual level. Consideration of how these core components translate to the population level will be necessary for successful implementation of programs and payment systems aimed at enhancing population health, such as wellness promotion models and accountable care organizations.

The increased importance of patient-centered care in health reform has implications for occupational therapy education. The ACA endorses training in patient centeredness for all health professions and interdisciplinary approaches to care delivery. Moreover, an Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel (2011) report identified effective delivery of patient-centered care as one of the four domains of core interprofessional competencies. Therefore, the occupational therapy profession must explore the most effective methods to train future practitioners not only in how to practice client-centered occupational therapy but also in how to work on interprofessional teams that promote patient-centered care.

Because emphasis on completing certain aspects of training outside of practice silos is becoming more common in health care education, and because patient centeredness cuts across professions, interprofessional training in patient-centered practice is a possible future direction for occupational therapy education. Although some occupational therapy programs already include a form of interprofessional education, references to interdisciplinary education and knowledge are limited in the current Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (2012) standards and model curricula (AOTA, 2008a, 2008b) and are nonexistent in the “Blueprint for Entry-Level Education” (AOTA, 2010).

As a profession with a knowledge base in client centeredness, occupational therapy has an opportunity to be a leader in this area. Current occupational therapy education provides practitioners with skills for collaborative goal setting, client education, and support for clients in participation, as well as with an understanding of the greater contexts that affect the client, all of which contribute to patient-centered care. However, the profession needs to be able to clearly articulate how current training fosters patient-centered care using language not specific to occupational therapy so that practitioners can communicate these abilities to other professionals.

Next Steps for Occupational Therapy

Recognition is growing that high-quality health care is contingent in part on the patient’s experience of care and that patient-centered care may improve outcomes (de Silva, 2014; Fredericks et al., 2015; IOM, 2001; NQF, 2014; Rathert et al., 2013; Stiefel & Nolan, 2012). The shift toward value-based reimbursement in health care challenges occupational therapy practitioners to demonstrate their unique contributions to patient care and resulting outcomes. Occupational therapy’s longstanding philosophy of client-centered care is one strategy to help showcase its value, but the profession must be aware of limitations in how client-centered principles currently translate to practice (Gupta & Taff, 2015).

Occupational therapy needs to be part of the discussion around patient-centered care not only for the sake of demonstrating the profession’s worth in a system undergoing a sea change toward value but also for the sake of our clients. We have expertise to share with other health professionals, researchers, and policymakers. The profession should disseminate its insights into client centeredness, further develop its understanding of and research agenda around client centeredness, and ensure practitioners’ continuing competence in core components of client-centered care to align occupational therapy with the priorities of health reform.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christina Metzler for her helpful feedback during the writing process. Drs. Fogelberg and Leland were supported by the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, National Institutes of Health, during the development of this manuscript (K01HD076183 and K12HD055929, respectively).

Contributor Information

Tracy M. Mroz, Tracy M. Mroz, PhD, OTR/L, is Assistant Professor, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle; tmroz@uw.edu

Jennifer S. Pitonyak, Jennifer S. Pitonyak, PhD, OTR/L SCFES, is Assistant Professor, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle

Donald Fogelberg, Donald Fogelberg, PhD, OTR/L, is Assistant Professor, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle.

Natalie E. Leland, Natalie E. Leland, PhD, OTR/L, BCG, FAOTA, is Assistant Professor, Mrs. T. H. Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, and Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles

References

- Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education. (2012). 2011 Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE®) standards and interpretive guide. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(6, Suppl.), S6–S74. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2012.66S6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2008a). Occupational therapy assistant model curriculum. Bethesda, MD: Author; Retrieved from http://www.aota.org/-/media/Corporate/Files/EducationCareers/Educators/Model%20OTA%20Curriculum%20-%20October%202008.pdf [Google Scholar]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2008b). Occupational therapy model curriculum. Bethesda, MD: Author; Retrieved from http://www.aota.org/-/media/Corporate/Files/EducationCareers/Educators/FINAL%20Copy%20Edit%20OT%20Model%20Curriculum%20Guide%2012-08.pdf [Google Scholar]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2010). Blueprint for entry-level education. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64, 186–203. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.64.1.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2014). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (3rd ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(Suppl. 1), S1–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berges I.-M., Seale G. S., & Ostir G. V. (2012). The role of positive affect on social participation following stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34, 2119–2123. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.673684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick D. M., Nolan T. W., & Whittington J. (2008). The Triple Aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Affairs, 27, 759–769. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing R. K. (1981). Occupational therapy revisited: A paraphrastic journey (Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 35, 499–518. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.35.8.499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. (1997). Enabling occupation: An occupational therapy perspective. Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. (2002). Enabling occupation: An occupational therapy perspective (rev. ed.). Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. (2013). Enabling occupation II: Advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being, and justice through occupation (2nd ed.). Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, & Department of National Health and Welfare. (1983). Guidelines for the client-centred practice of occupational therapy. Ottawa: Department of National Health and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Carswell A., McColl M. A., Baptiste S., Law M., Polatajko H., & Pollock N. (2004). The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: A research and clinical literature review. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71, 210–222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000841740407100406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cott C. A. (2004). Client-centred rehabilitation: Client perspectives. Disability and Rehabilitation, 26, 1411–1422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09638280400000237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cott C. A., Teare G., McGilton K. S., & Lineker S. (2006). Reliability and construct validity of the Client-Centred Rehabilitation Questionnaire. Disability and Rehabilitation, 28, 1387–1397. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09638280600638398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin C. (2004). Patient-centered care: An overview of definitions and concepts. Washington, DC: National Health Council. [Google Scholar]

- Dedding C., Cardol M., Eyssen I. C., Dekker J., & Beelen A. (2004). Validity of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: A client-centred outcome measurement. Clinical Rehabilitation, 18, 660–667. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0269215504cr746oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva D. (2014). Helping measure person-centred care: Evidence review. London: Health Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Doig E., Prescott S., Fleming J., Cornwell P., & Kuipers P. (2015). Development and construct validation of the Client-Centredness of Goal Setting (C–COGS) scale. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 22, 302–310. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2015.1017530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enemark Larsen A., & Carlsson G. (2012). Utility of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure as an admission and outcome measure in interdisciplinary community-based geriatric rehabilitation. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 19, 204–213. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2011.574151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R. M., Fiscella K., Lesser C. S., & Stange K. C. (2010). Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Affairs, 29, 1489–1495. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R. M., & Street R. L. Jr (2011). The values and value of patient-centered care. Annals of Family Medicine, 9, 100–103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1370/afm.1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyssen I. C., Steultjens M. P., Oud T. A., Bolt E. M., Maasdam A., & Dekker J. (2011). Responsiveness of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 48, 517–528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2010.06.0110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks S., Lapum J., & Hui G. (2015). Examining the effect of patient-centred care on outcomes. British Journal of Nursing, 24, 394–400. http://dx.doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2015.24.7.394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J., & Taff S. D. (2015). The illusion of client-centred practice. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 22, 244–251. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2015.1020866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammell K. R. (2013). Client-centred practice in occupational therapy: Critical reflections. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 20, 174–181. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2012.752032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg S. R. (1990). Client or patient: Which term is more appropriate for use in occupational therapy? American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 44, 561–564. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.44.6.561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudon C., Fortin M., Haggerty J. L., Lambert M., & Poitras M. E. (2011). Measuring patients’ perceptions of patient-centered care: A systematic review of tools for family medicine. Annals of Family Medicine, 9, 155–164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1370/afm.1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudon C., Fortin M., Haggerty J., Loignon C., Lambert M., & Poitras M.-E. (2012). Patient-centered care in chronic disease management: A thematic analysis of the literature in family medicine. Patient Education and Counseling, 88, 170–176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMPACT (Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation) Act, Pub. L. 113–185, 42 U.S.C. §1305 (2014).

- Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative. [Google Scholar]

- Kitson A., Marshall A., Bassett K., & Zeitz K. (2013). What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69, 4–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjellberg A., Kåhlin I., Haglund L., & Taylor R. R. (2012). The myth of participation in occupational therapy: Reconceptualizing a client-centred approach. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 19, 421–427. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2011.627378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortte K. B., Gilbert M., Gorman P., & Wegener S. T. (2010). Positive psychological variables in the prediction of life satisfaction after spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55, 40–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortte K. B., Stevenson J. E., Hosey M. M., Castillo R., & Wegener S. T. (2012). Hope predicts positive functional role outcomes in acute rehabilitation populations. Rehabilitation Psychology, 57, 248–255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0029004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyler P. L. (2008). Client-centered and family-centered care: Refinement of the concepts. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 24, 100–120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01642120802055150 [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Baptiste S., Carswell A., McColl M. A., Polatajko H., & Pollock N. (1990). Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE. [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Baptiste S., & Mills J. (1995). Client-centred practice: What does it mean and does it make a difference? Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 250–257. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000841749506200504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M., & Mills J. (1998). Client-centred occupational therapy. In Law M. (Ed.), Client-centered occupational therapy (pp. 1–18). Thorofare, NJ: Slack. [Google Scholar]

- Leland N. E., Crum K., Phipps S., Roberts P., & Gage B (2015). Health Policy Perspectives—Advancing the value and quality of occupational therapy in health service delivery. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69, 6901090010 http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.691001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maitra K. K., & Erway F. (2006). Perception of client-centered practice in occupational therapists and their clients. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60, 298–310. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.60.3.298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly C. (2010). The paradox of hope: Journeys through a clinical borderland. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Metzler C. A., Hartmann K. D., & Lowenthal L. A. (2012). Defining primary care: Envisioning the roles of occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66, 266–270. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2010.663001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millenson M. L., & Macri J. (2012). Will the Affordable Care Act move patient-centeredness to center stage? [Policy Brief]. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; Retrieved from http://www.urban.org/publications/412524.html [Google Scholar]

- Moyers P. A., & Metzler C. A. (2014). Interprofessional collaborative practice in care coordination. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68, 500–505. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2014.685002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Quality Forum. (2014). Priority setting for healthcare performance measurement: Addressing performance measure gaps in person-centered care and outcomes. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- National Quality Forum. (2015). NQF-endorsed measures for person- and family-centered care: Phase 1. Technical report. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. (2012). 2012 annual report. Washington, DC: Author; Retrieved from http://www.pcori.org/assets/2013/08/PCORI-Annual-Report-2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. 111–148, 42 U.S.C. §18001 (2010).

- Pitonyak J. S., Mroz T. M., & Fogelberg D. (2015). Expanding client-centred thinking to include social determinants: A practical scenario based on the occupation of breastfeeding. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 22, 277–282. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2015.1020865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovich J. M., Fox P. G., & Burns K. R. (2003). “Hope” in the recovery from stroke in the U.S. International Journal of Psychiatric Nursing Research, 8, 905–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathert C., Wyrwich M. D., & Boren S. A. (2013). Patient-centered care and outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Medical Care Research and Review, 70, 351–379. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077558712465774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebeiro K. L. (2000). Client perspectives on occupational therapy practice: Are we truly client-centered? Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67, 7–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000841740006700103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly M. (1984). The importance of the client versus patient issue for occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 38, 404–406. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.38.6.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrott G. W., & Yerxa E. J. (1985). Promises to keep: Implications of the referent “patient” versus “client” for those served by occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 39, 401–405. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.39.6.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J., Davidson H., & White V. (1997). Help clients develop hopes for the future. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51, 191–198. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.51.3.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiefel M., & Nolan K. (2012). A guide to measuring the Triple Aim: Population health, experience of care, and per capita cost [IHI Innovation Series white paper]. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. [Google Scholar]

- Sumsion T., & Law M. (2006). A review of evidence on the conceptual elements informing client-centred practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73, 153–162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000841740607300303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend E., Brintnell S., & Staisey N. (1990). Developing guidelines for client-centred occupational therapy practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57, 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E. H., Bennett S. M., Austin B. T., Greene S. M., Schaefer J. K., & Vonkorff M. (2005). Finding common ground: Patient-centeredness and evidence-based chronic illness care. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 11(Suppl. 1), S7–S15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/acm.2005.11.s-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood J. P., Connelly D. M., & Maly M. R. (2010). “Getting back to real living”: A qualitative study of the process of community reintegration after stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation, 24, 1045–1056. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0269215510375901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]