Abstract

Introduction:

DOG1 is a transmembrane protein originally “discovered on gastrointestinal stromal tumors,” works as a calcium-activated chloride channel protein. There is a limited number of studies on the potential usage of this antibody in the diagnosis of salivary gland tumors on routine practice in cell blocks. The aim of this study was to search for the usefulness of K9 clone in oncocytic type tumors and review of the literature.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty-nine fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytologic materials of predominantly oncocytic morphology salivary gland tumors; acinic cell carcinoma (AciCC) (n = 8), adenoid cystic carcinoma (n = 2), pleomorphic adenoma (PA) (n = 22), Warthin tumor (WT) (n = 20), myoepithelioma (ME) (n = 5), benign oncocytoma (BeO) (n = 3), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) (n = 7), mammary analog salivary gland carcinoma (n = 2) were immunostained with DOG1 (clone K9) stain.

Results:

Of the 8 AciCCs, 7 were observed apical-luminal positive staining, demonstrating 1–3 + intensity, and involving 40–70% of the tumor cells. One MEC of 7 (14%), 1 ME of 5 (20%), and 4 PA of 22 (18%) showed weak (1+) cytoplasmic granular staining in 5–10% of the tumor cells. Pure oncocytic neoplasms (WT, BeO) showed no expression with DOG1-K9.

Conclusions:

FNA is a common tool in the diagnosis and management of salivary gland tumors. DOG1-K9 clone was very useful with a unique staining pattern of apical-luminal positivity in the differential diagnosis of AciCC from other oncocytic salivary gland tumors.

Keywords: Acinic cell carcinoma, clone K9, DOG1, fine needle aspiration biopsy, salivary gland

INTRODUCTION

As a third common malignancy of salivary gland; acinic cell carcinoma (AciCC)[1] is a rare, yet, cytomorphologically intriguing epithelial malignant neoplasm. AciCC is accounting for 1–6% of all salivary gland tumors that are mostly seen in the parotid gland, young female patients.[1] Despite a low-grade malignant behavior of AciCC, the recurrences and metastasis customarily can be seen in the aggressive behavior, particularly to the lung, and cervical lymph nodes.[2] The diagnostic perplexity of AciCC arises from the broad differential diagnosis including both malignant and benign entities of the salivary gland on cytopathology specimens. False negative diagnosis reported as 43% in fine needle aspiration (FNA) due to the resemblance of neoplastic cells to the normal serous acinar cells, at times, misinterpretation as benign salivary gland or sialoadenosis can be probable.[3,4] The neoplastic mimickers largely include oncocytic morphology salivary gland neoplasms (e.g. Warthin tumor [WT], pleomorphic adenoma [PA], benign oncocytoma [BeO], some myoepithelioma [ME]) that are mostly benign.[1,3] However, 10–15% of the AciCC cases can be found with metastasis to the local lymph nodes, thus, differentiating AciCC from those benign entities is crucial.[2] Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC), mammary analog salivary gland carcinoma (MASC) are well known malignant mimickers, which also have oncocytic morphology.[5,6] Rarely, oncocytic changes may seen in adenoid cystic carcinoma (ADC) and create a confliction in the differential diagnosis of AciCC. Cytomorphologic findings and also immunohistochemistry have a limited value to discriminate AciCC from predominantly oncocytic morphology salivary gland neoplasms. Lately, DOG1 has been issued in the literature, which is a transmembrane protein originally discovered on GIST1, works as a calcium-activated chloride channel protein.[7,8,9] Interestingly, there are a limited number of studies on the value of DOG1 in salivary gland, particularly focused on AciCC.[4,10] Previous studies on the validation of DOG1 in the diagnosis of AciCC designed with different clones of DOG1.[4,7,10] They showed different staining patterns, intensity, and also extensity. Due to the clonal variability of DOG1 and limited number of studies, may create a confusion on the role of DOG1 in the diagnosis of AciCC.

So far, there has been few articles about the value of DOG1 in the diagnosis of AciCC in pathological specimens and much lesser in the FNA cell block specimens.[4,10] To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that analyze the value for DOG1-K9 on the cytology specimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case and specimen selection

Cases were retrieved from the archives at the Haydarpasa Numune Education and Research Hospital cytopathology files between 2004 and 2014. The study group contained 69 cases of predominantly oncocytic morphology salivary gland tumors. All cases were confirmed by pathology resection specimens. Cases were selected from the great mimickers of AciCC which are primarily composed of oncocytic morphology neoplasms; AciCC (n = 8), ADC (n = 2), PA (n = 22), WT (n = 20), ME (n = 5), BeO (n = 3), MEC (n = 7), MASC (n = 2) Figure composite 1. Cases without sufficient tumor cells in cell blocks and histopathologic diagnosis were excluded. Sixty-nine cell blocks were stained with DOG1 (clone K9) immunostain.

DOG1 (clone K9) immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining for DOG1-K9 (1:100 dilution; Novocastra/Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) was performed on cell blocks with an automated immunostaining platform, Ventana Benchmark XT (Ventana Medical Systems Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA) on serially sectioned 4-micron paraffin-embedded cell blocks according to the manufacturer's instructions. DOG1-K9 positive gastrointestinal stromal tumor was used as external positive and negative control.

Evaluation

Cell block specimens were considered as positive when 5% of tumor cells stained apical/luminal for DOG1-K9. Staining intensity is graded by scoring normal serous acinar cells as (2+), less intense positivity as (1+), and more strong positivity as (3+). Subcellular localization of the staining pattern (cytoplasmic, membranous, and luminal) are also taken into consideration.

RESULTS

Of the 8 AciCCs, only 1 (12%) had no expression with DOG1-K9. The rest of 7 AciCCs were observed apical-luminal positive staining, demonstrating 1–3 + intensity, and involving 40–70% of the tumor cells. The one had no expression with DOG1-K9 was poorly differentiated AciCC, while the other 7 cases were well to moderate differentiated AciCC.

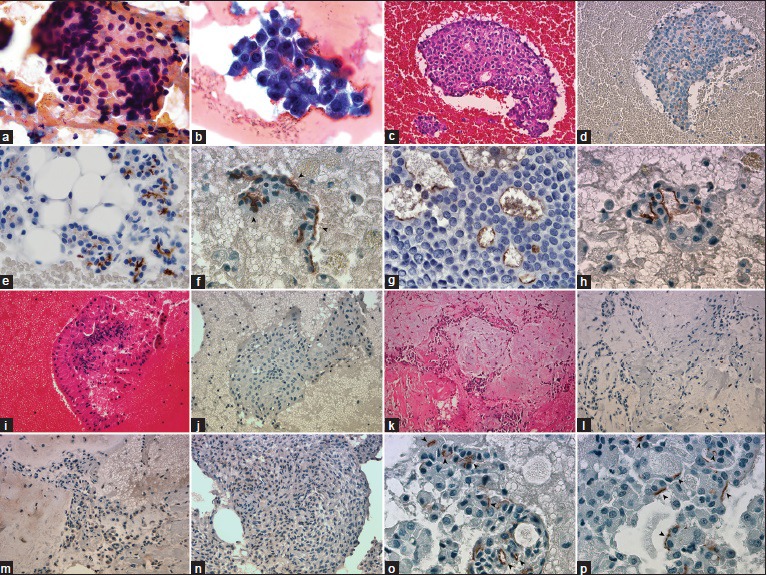

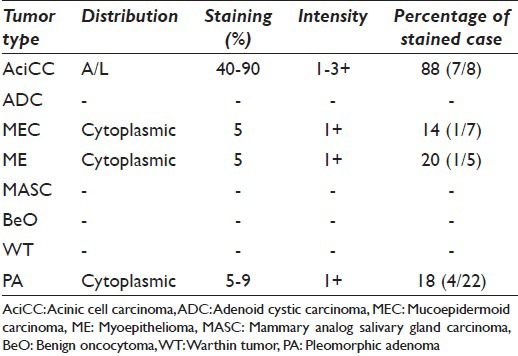

One MEC of 7 (14%), 1 ME of 5 (20%), and 4 PA of 22 (18%) showed weak (1+) cytoplasmic granular staining in 5–10% of the tumor cells. Pure oncocytic neoplasms (WT, BeO) showed no expression with DOG1-K9. Between the case population, only AciCC showed specific staining pattern, which detected as apical-luminal [Figure 1 and Table 1].

Figure 1.

(a) Large granular cytoplasm with round eccentrically located nuclei (PAP, ×1000). (b) Clusters are composed of malignant acinar cells, thin-granular large cytoplasm, and mildly atypical nuclei (Diff-Quik, ×1000). (c) Cell block of acinic cell carcinoma (H and E, ×400). (d) DOG1-K9 clone shows diffuse apical-luminal expression in acinic cell carcinoma (Immunohistochemistry, ×400). (e) Apical-luminal staining (2+) in normal serous acinar cells (Immunohistochemistry, ×1000). (f-h) Apical-luminal staining in acinic cell carcinomas, (1+, 2+, 3+), respectively, (Immunohistochemistry, ×1000). (i) Warthin Tumor is easily recognized with mature lymphocytes wrapping oncocytic cells (H and E, ×400). (k-m) Cell block of pleomorphic adenoma, areas of focal weak cytoplasmic granular positivity, and negativity in the identical case (H and E and Immunohistochemistry, ×400). (n) Focal, weak cytoplasmic granular staining in myoepithelioma case (Immunohistochemistry, ×400). (o and p) Apical-luminal staining (subcellular localization) in acinic cell carcinomas, (Immunohistochemistry, ×1000)

Table 1.

Demonstrates DOG1-K9 staining in our cases

DISCUSSION

FNA biopsy is a widely approved diagnostic procedure in salivary gland tumors before the definitive treatment including management of surgery.[11] There is a well-documented diagnostic perplexity reported by numerous studies in the literature. At times, discriminate benign entities from malignant ones is a bane of the pathologist owing to its heterogeneous cytomorphology in salivary gland tumors.[11] The overall sensitivity and specificity of all salivary gland tumors were estimated between 64% and 99%, respectively.[3,6] Overall diagnostic accuracy was reported in a wide range from 50% to 90%.[1] Fortuitously, primary salivary gland carcinomas are rare accounting for approximately 0.5% of all malignancies and lesser than 5% of all head and neck cancers.[2,12] However, 24 different malignant subtypes of salivary gland carcinomas endorsed by the World Health Organization blue book 2005 with a broad tumor heterogeneity, clinical outcome, and varying prognoses.[12,13] Surgical excision is the first step and benign tumors needed to be distinguished from the malignant ones to set up the correct surgical management.[2] Malignant salivary gland tumors must be evaluated for neck dissection when metastatic lymph nodes are present and adjuvant chemotherapy or in combination with radiotherapy are the choices according to the tumor type, grade, size, clinical stage, nerve invasion or recurrence.[12,14] The most common malignant salivary gland tumors; MEC and ADC must be taken in the differential diagnosis of AciCC, in addition to great mimicker MASC.[5] Well-prepared slides with high cellularity and presence of cytopathologist may harbor better performance in the accurate diagnosis. AciCC is a low-grade malignant tumor and associated changes such as; necrosis, metaplasia, degeneration, infarct, sampling error, preparation artifacts easily may cause misinterpretation. If not alerted by any of those changes above, a misdiagnosis will be inevitable.[1] Furthermore, both AciCC and oncocytic lesions (Warthin, oncocytomas) as its mimickers are rather vulnerable to those changes, exclusively to infarction.[1]

AciCC is reported a recurrence rate between 12% and 35% and the 5 years survival of 83.3%.[2] Differential diagnosis includes vast majority of benign and a few malignant salivary gland tumors due to the cytomorphology of sampling.[1] Cells are usually round, polygonal with large cytoplasm. Cytoplasm is mostly seen granular due to the presence of azurophilic granules. Nuclei also have sweet roundness and uniformity. Binucleation can occur. Chromatin texture might be fine to moderate coarse and nucleoli are not necessarily prominent. High cellularity, large groups, papillae, acinar structures are the important clues. Low-grade AciCCs are bland, hard to differentiated from normal acinar cell groups in the samples with poor cellularity.[1,6] Adequacy of the yield influenced by the nature of the lesion besides the experience of the radiologist.[1]

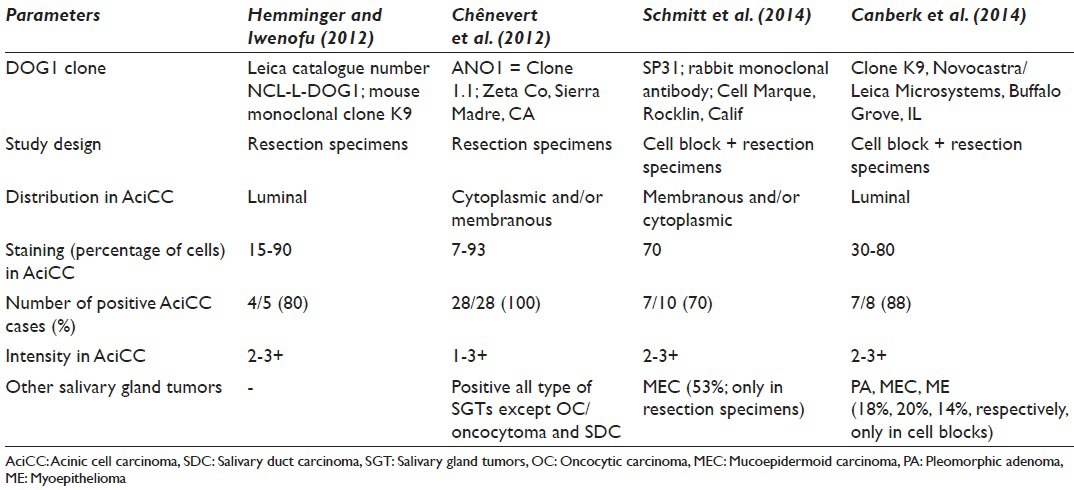

Schmitt investigated for p63, S100, and DOG1 antibodies in terms of differentiating the oncocytic neoplasms of the salivary gland.[4] DOG1-sp31 was first studied using cell blocks and pathology specimens; diffuse, moderately-strong, membranous/cytoplasmic positive staining was noted in 70% of AciCCs with the clone.[4] Interestingly, both patterns and staining intensity were different. On the contrary of AciCC that has moderate to strong membranous/cytoplasmic expression, normal acinar cells were demonstrated focal-faint apical luminal membranous staining. A question comes to mind; does DOG1-sp31 clone be able to distinguish malignant acinar cells from the benign ones? In our study, no matter benign or malignant nature, acinar cells always showed an apical-luminal pattern with DOG1-K9 clone. Another question about the study of Schmitt;[4] if also MEC expressed focal-faint DOG1-sp31 in 53% and exactly the same pattern as well as AciCC in resection specimens, even no expression has observed in cell blocks for the same tumor population; could it be possible to use alone or in a panel for differentiating AciCC from MEC confidently? Although, faint focal membranous and cytoplasmic positivity in MEC was noted in our study, yet, the staining pattern of AciCC seemed to be specific for acinar cell nature. The common finding of DOG1-sp31 and DOG1-K9 studies was the lack of any staining in pure oncocytic neoplasms; WT and oncocytoma.

Similar to the current study, Chênevert et al.[10] searched for DOG1 staining in the normal salivary gland and in the tumors originating from the salivary glands with a different clone DOG1-ANO1 and in tissue sections. Unlike the unique apical-luminal strong positivity with K9 clone, AciCCs showed scattered cytoplasmic and complete membranous positivity besides apical membranous staining. Furthermore, 75% of ADCs, 47% of myoepithelial carcinomas, 60% of MECs showed some apical-luminal positivity in ductal and cytoplasmic-membranous positivity in myoepithelial components. Although it appeared that diffuse and strong apical and membranous staining favors the diagnosis of AciCC, intersecting staining patterns between different neoplasias made somewhat hard to differentiate these entities by using DOG1-ANO1.

Hemminger and Iwenofu[7] found that 4/5 of AciCCs were showing moderate to strong luminal expression with the DOG1-K9 clone in the comparison pathology study between gastrointestinal stromal tumors and nongastrointestinal stromal tumor neoplasms. This finding correlates with our finding that the staining pattern was only apical-luminal, whereas other clones of DOG1 presented cytoplasmic/membranous staining, was seen not only in AciCC but also in other tumors [Table 2].

Table 2.

The similar studies with different type of clones of DOG1 in the literature including both pathology/cytopathology specimens of salivary gland tumors

DOG1-K9 represented selectivity to acinar cell nature, regardless of the biologic behavior. This led us to believe that the DOG1-K9 clone is significantly specific comparing to other clones of DOG1 in the diagnosis of AciCC. Nonetheless, further studies are needed to be analyzed with large groups of tumors to support our promising results.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article. S.C designed the project and the study, wrote the manuscript. M.O and E.S helped to these parts and carried out the figures. C.G carried out the acquisition of the data and financially supported the study with S.C. Pathology diagnosis were confirmed by M.E. All biopsies were performed by G.K and T.A.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was retrospectively designed using archival materials, therefore spesific written informed consents had obtained from the patients before performing FNA. All authors take the responsibility of maintaining relevant documentation of records, slides and other data used in this study on archival material as per the institutional policy.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

AciCC - Acinic Cell Carcinoma

ADC - Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma

BeO - Benign Oncocytoma

FNA - Fine Needle Aspiration

MASC - Mammary Analog Salivary Gland Carcinoma

ME - Myoepithelioma

MEC - Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma

PA - Pleomorphic Adenoma

WT - Warthin Tumor.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are gratefully thankful for continued support and encouragement to Dr. F.V.Aker (the head of department) and offering sincere appreciation for some cases of Drs. K. Behzatoglu and G.E. Huq that shared with us. (Istanbul Education and Research Hospital, Pathology Department).

Contributor Information

Sule Canberk, Email: sulecanberk@icloud.com.

Mine Onenerk, Email: monenerk@yahoo.com.tr.

Elif Sayman, Email: saymanelf @gmail.com.

Ceren Canbey Goret, Email: drcerencanbey@hotmail.com.

Murat Erkan, Email: mumuerkan@gmail.com.

Tugba Atasoy, Email: tuba_tip@yahoo.com.

Gamze Z. Kilicoglu, Email: gamze@kilicoglu.nom.tr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Demay R.M., 2nd Edition rt Sci Cytopathol. 2011;2:777–818. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ettl T, Schwarz-Furlan S, Gosau M, Reichert TE. Salivary gland carcinomas. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;16:267–83. doi: 10.1007/s10006-012-0350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes JH, Volk EE, Wilbur DC. Cytopathology Resource Committee, College of American Pathologists. Pitfalls in salivary gland fine-needle aspiration cytology: Lessons from the College of American Pathologists Interlaboratory Comparison Program in Nongynecologic Cytology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:26–31. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-26-PISGFC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmitt AC. DOG1, p63, and S100 protein: A novel immunohistochemical panel in the differential diagnosis of oncocytic salivary gland neoplasms in fine-needle aspiration cell blocks. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2014;3:303e–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellevicine C, Natella V, Somma A, De Rosa G, Troncone G. MASC is indistinguishable from acinic cell carcinoma, papillary-cystic variant on salivary gland FNA cytomorphology: Case report with histological and immunohistochemical correlates. Cytopathology. 2014;25:344–6. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukunyadzi P. Review of fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland neoplasms, with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118(Suppl):S100–15. doi: 10.1309/WVVR-30E4-13TW-494D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemminger J, Iwenofu OH. Discovered on gastrointestinal stromal tumours 1 (DOG1) expression in non-gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) neoplasms. Histopathology. 2012;61:170–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong NA, Shelley-Fraser G. Specificity of DOG1 (K9 clone) and protein kinase C theta (clone 27) as immunohistochemical markers of gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Histopathology. 2010;57:250–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes LF, West RB, Bacchi LM, van de Rijn M, Bacchi CE. DOG1 for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): Comparison between 2 different antibodies. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2010;18:333–7. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181d27ec8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chênevert J, Duvvuri U, Chiosea S, Dacic S, Cieply K, Kim J, et al. DOG1: A novel marker of salivary acinar and intercalated duct differentiation. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:919–29. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colella G, Cannavale R, Flamminio F, Foschini MP. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions: A systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shigeishi H, Ohta K, Okui G, Seino S, Hashikata M, Yamamoto K, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of salivary gland carcinomas and literature review. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:202–6. doi: 10.3892/mco.2014.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eveson JW, Auclair P, Gnepp DR, El-Naggar AK. Tumours of the salivary galnads. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours (IARC WHO Classification of Tumours) Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tryggvason G, Gailey MP, Hulstein SL, Karnell LH, Hoffman HT, Funk GF, et al. Accuracy of fine-needle aspiration and imaging in the preoperative workup of salivary gland mass lesions treated surgically. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:158–63. doi: 10.1002/lary.23613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]