Abstract

Within the last twenty years the view on reactive oxygen species (ROS) has changed; they are no longer only considered to be harmful but also necessary for cellular communication and homeostasis in different organisms ranging from bacteria to mammals. In the latter, ROS were shown to modulate diverse physiological processes including the regulation of growth factor signaling, the hypoxic response, inflammation and the immune response. During the last 60–100 years the life style, at least in the Western world, has changed enormously. This became obvious with an increase in caloric intake, decreased energy expenditure as well as the appearance of alcoholism and smoking; These changes were shown to contribute to generation of ROS which are, at least in part, associated with the occurrence of several chronic diseases like adiposity, atherosclerosis, type II diabetes, and cancer. In this review we discuss aspects and problems on the role of intracellular ROS formation and nutrition with the link to diseases and their problematic therapeutical issues.

Keywords: Free radicals, Diets, Oxygen, Metabolism, Diseases, Mitochondria, Hypoxia, Diabetes, Obesity

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Oxidative stress is linked to overnutrition, obesity and associated diseases or cancer.

-

•

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are crucially involved in modulation of signaling cascades.

-

•

NOX proteins and hypoxia contribute to formation of ROS under different nutrient regimes.

-

•

ROS are powerful post-transcriptional and epigenetic regulators.

-

•

Treatment of obesity with antioxidants requires more, larger, and better monitored clinical trials.

1. Introduction

The research within the last twenty years on chemically reactive molecules containing oxygen, commonly called reactive oxygen species (ROS), has shown that these molecules are important for cellular communication and homeostasis in different organisms ranging from bacteria to mammals. Thereby, ROS were shown to modulate diverse physiological processes including the regulation of growth factor signaling, the hypoxic response, inflammation and the immune response in mammalian cells. ROS are often simply called “free radicals” because their majority is characterized by at least one unpaired electron in their outer orbitals; however, peroxides like hydrogen peroxide may also give rise to the formation of oxygen radicals and are therefore also considered as ROS. Frequently the incomplete reduction of oxygen by one electron producing superoxide anion () is the first step for the formation of most other ROS [1,2].

The action of ROS is usually balanced by the antioxidative capacity of a cell or organism and a disturbance of this balance in favor of a prooxidant state is commonly referred to as oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is usually coupled to harmful effects due to the primary chemical reactions of ROS with lipids and proteins. In this respect, diseases frequently associated with a Western lifestyle and nutritional regime like type II diabetes, cardiovascular diseases or cancer were found to be associated with a deregulated ROS formation [3–7]. Hence, it appears to be of special interest that production of ROS due to nutrition may affect signaling pathways and the pathogenesis of these diseases. In the current review we aim to summarize some aspects on the role of ROS, nutrition, intracellular ROS formation, and the link to diseases.

2. Cellular sources of ROS

A number of studies within the last decade indicated that overnutrition-induced ROS formation and oxidative stress contribute to the development of metabolic disorders, in particular to insulin resistance, as well as to cardiovascular diseases, and cancer [8–12].

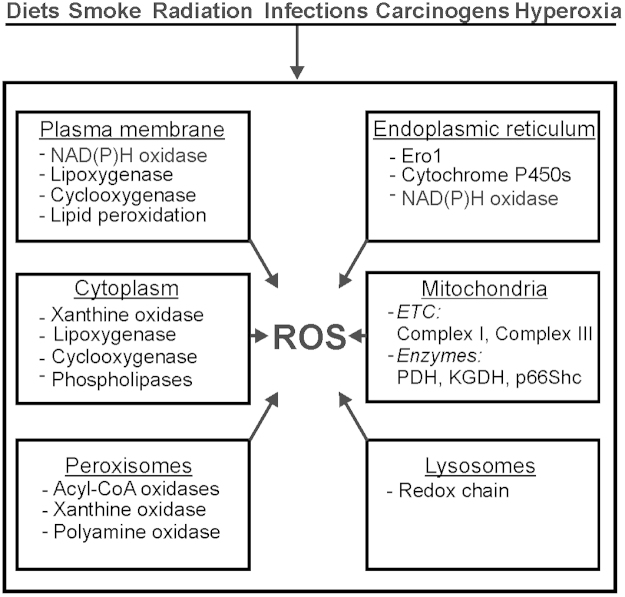

In mammalian cells ROS can be generated in different cellular compartments such as membranes, cytoplasm, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), lysosomes, and peroxisomes (Fig.1). In the following we will give only a short summary because the role of each compartment in ROS formation has been discussed elsewhere in excellent detail [13].

Fig. 1.

ROS generation in cells. ROS can be generated in response to various stimuli among them diets or radiation which is supported by the action(s) of enzyme(s) located in different intracellular compartments. ETC, electron transport chain;

2.1. Plasma membranes and ROS production

The prototypic NADPH oxidase was found in phagocytes localized in the plasma membrane and phagosomes [14]. It is composed of gp91phox and the smaller subunit p22phox forming the flavocytochrome b558 [15,16] which is the catalytic core of the NADPH oxidase generating . Several homologs of gp91phox – now termed NOX2-named NOX1-5, and the more distantly related DUOX1/2 (dual oxidases) were found [17–19]. NOX2 is mainly expressed in polymorphonuclear cells, macrophages and endothelial cells, but its expression was also verified in other cell types including cells from the CNS, smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, cardiomyocytes, skeletal muscle, hepatocytes, and hematopoietic stem cells [20] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of the NOX family members (see text for details and references)

| Name | Subcellular localization | Expression# | Cofactors |

| NOX1 | Caveolae membrane | Colon epithelia | p22phox |

| NOXO1 | |||

| Smooth muscle cells | |||

| Endothelial cells | |||

| Endosomes | |||

| Uterus | NOXA1 | ||

| Placenta | |||

| Nucleus | |||

| p47phox(?) | |||

| Pancreatic islet beta cells | |||

| RAC 1 | |||

| NOX2 | Plasma membrane | Neutrophils | p22phox |

| Macrophages | |||

| Endothelial cells | p40phox | ||

| Central nervous system | |||

| Smooth muscle cells | p47phox | ||

| Fibroblasts | |||

| Phagosomes | Cardiomyocytes | p67phox | |

| Skeletal muscle | |||

| Hepatocytes | |||

| RAC 1/2 | |||

| Hematopoietic stem cells | |||

| NOX3 | Fetal tissues | p22phox | |

| NOXO1 | |||

| Inner ear | |||

| Hepatoblastoma cell line HepG2 | |||

| NOXA1 | |||

| Murine Macrophage cell line RAW264.7 | |||

| P47phox(?) | |||

| Murine lung endothelium | |||

| RAC 1 | |||

| NOX4 | Endoplasmic reticulum | Kidney | p22phox |

| Endothelial cells | |||

| Smooth muscle cells | RAC 1(?) | ||

| Outer nucleus membrane | |||

| Fibroblasts | |||

| Hepatocytes | |||

| NOX5a | Endoplasmic reticulum | Testis | Ca2+ |

| Prostate | |||

| Spleen | Calmodulin | ||

| Lymph nodes | |||

| Endothelial cells | |||

| Smooth muscle cells | |||

| DUOX1/2 | Endoplasmic reticulum | Thyroid | Ca2+ |

| Plasma membrane | Lung epithelium | ||

| DUOX1/2 | |||

| Gastrointestinal tract | |||

NOX5 is not present in rodents.

Most relevant expression listed with no claim to completeness.

NOX1 is highly expressed in the colon epithelia [21] and was also detected in lower abundance in smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, uterus, placenta, pancreatic islet beta cells and other cell types [22,23]; it is mainly localized in the plasma membrane of caveolae, but also in early endosomes or nucleus [24,25].

NOX3 has long been considered to be expressed in fetal tissues, but is it now also found in the inner ear, HepG2 cells, the mouse macrophage cell line RAW264.7, and in murine lung endothelium [26] (Table 1).

NOX4 is widely expressed in many tissues, especially in the kidney [27], but also in most other tissues and cells including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts and hepatocytes [25,28–30]. In contrast to most other NOXes, NOX4 is mainly localized in the endoplasmic reticulum as well as in the outer membrane of the nucleus [31,32]. Finally, NOX5 expression has been detected in testis, prostate, spleen, lymph nodes, but also in endothelial and smooth muscle cells [26] and its mainly localized in the endoplasmic reticulum of the cell [33] (Table 1).

The two DUOX1/2 proteins are highly expressed in the thyroid, but also in lung epithelium and gastrointestinal tract [34–36]; mainly in the endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane [32].

Most NOXes as well as the two DUOX members require cytosolic subunits for full activation. In the case of NOX2 these are the cytosolic subunits p40phox, p47phox, p67phox as well as the small monomeric GTPase Rac [16]. NOX1 and NOX3 can be regulated by NOXO1 (p67phox homolog) and NOXA1 (p47phox homolog) while DUOX1 and -2 require their regulators DUOXA1 and DUOXA2, respectively [26,32]. NOX4 activity seems to be independent of regulatory subunits, though a role for Rac is discussed [26] and it is mainly regulated at the expression level. In addition to regulatory proteins, activation of NOX5 and DUOX1/2 requires calcium [17,33] and in case with NOX5 also calmodulin [37] (Table 1). Most generated ROS in non-phagocytic cells are mainly considered to act as second messenger molecules in several processes including responses to nutrition [26].

2.2. Mitochondria and ROS production

Mitochondria are well known to be major ROS producers [38] and the fraction of oxygen that is used for ROS production varies and ranges from 0.15% to 4% [39]. Interestingly, in females mitochondria produce less ROS than in males; a difference which can be seen also in the induced levels of antioxidant enzymes in females which is largely due to the action of estrogens [40]. The electron transport chain (ETC) within mitochondria constitutes an important source of formation primarily due to leaking electrons from complex I (NADH-CoQ reductase) and complex III (cytochrome c reductase). Thereby complex I generates only within the matrix, while complex III can contribute to formation also in the intermembrane space [41]. In addition to the ETC, also the acetyl-CoA generating enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and the Krebs cycle enzyme α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGDH) can be sources of [42–46]. Moreover, it was shown that the redox enzyme p66Shc is involved in the direct reduction of oxygen to H2O2 in the intermembrane space by using reducing equivalents through the oxidation of cytochrome C [47].

2.3. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and ROS production

The endoplasmic reticulum is a place with a high rate of ROS generation. On the one hand ER-localized ROS can be a byproduct of ER-localized oxygenases and oxidases during oxidative protein folding-among them endoplasmic oxidoreductin 1 (ERO1) as the most prominent one [13,48]. On the other hand there are also ER localized NADPH oxidases such as NOX4, NOX5, and DUOX1/2 which can contribute to ROS generation in the ER [31,33]. In addition, there is a crosstalk between enzymes of the protein folding machinery and NADPH oxidases due to a described interaction between PDI and NOX1/NOX4 as well as an interaction between calmodulin and NOX5 [37,49]. Further, ER localized iron deposits may also contribute to the pool of ROS by the formation of ·OH via a Fenton reaction [50].

2.4. Lysosomes and ROS production

Lysosomes are important organelles involved in degradation of intracellular and extracellular materials which interlinks them with phagocytosis, endocytosis and autophagy. To operate the degradative acidic hydrolases require a pH of about 4.8. To generate this pH, lysosomes appear to contain a redox chain which similar to the mitochondrial ETC contributes to proton distribution. As a byproduct ROS are generated. Thereby, reduction of O2 in three steps can give rise to ·OH generation [51]. Since lysosomes are degrading iron- and copper containing macromolecules they accumulate iron and copper. Due to the acidic and reducing lysosomal environment iron is mainly in the divalent, thus redox active, state whereas lysosomal copper is usually complexed with various thiols and is thus likely not redox-active [52]. Hence, the presence of divalent iron further fosters generation of ·OH by Fenton reactions which may affect lysosomal membrane integrity [52].

2.5. Peroxisomes and ROS production

Peroxisomes participate in several metabolic processes, including long-chain fatty acid β-oxidation, the oxidative part of the pentose phosphate pathway, phospholipid biosynthesis, purine, and polyamine metabolism as well as amino acid and polyamine oxidation [53]. Many of the enzymes operating in these pathways are flavin-dependent oxidases [53] which produce H2O2 as a result of their activity [54]. The major process forming H2O2 is β–oxidation of fatty acids whereas a peroxisomal xanthine oxidase appears to provide not only H2O2 but also [54]. Since H2O2 can give rise to formation of other ROS which could damage the cells, it needs to be degraded into per se non-reactive substances. This is done by the enzyme catalase which converts H2O2 into O2 and H2O [55].

2.6. Detrimental action of ROS

The harmful action of ROS is primarily due to their ability to oxidize and subsequently damage DNA, proteins and (membrane) lipids (Fig. 2). Among the ROS, ·OH are known to mainly damage DNA by reacting with all four bases whereas 1O2 selectively attacks guanine [56]; and H2O2 contribute indirectly to DNA damage by forming ·OH and lipid peroxides which contribute to formation of DNA adducts [57]. Again, most protein damage is exerted due to the action of ·OH at the protein polypeptide backbone [58]; as a consequence, further radicals such as peroxyl, alkylperoxide, or alkoxyl radicals are formed [59].

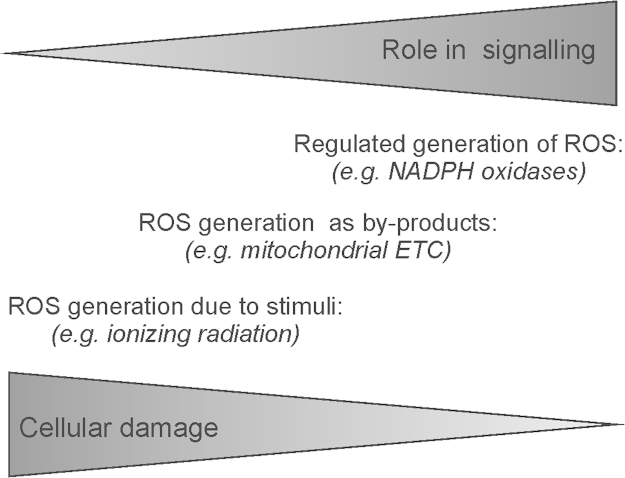

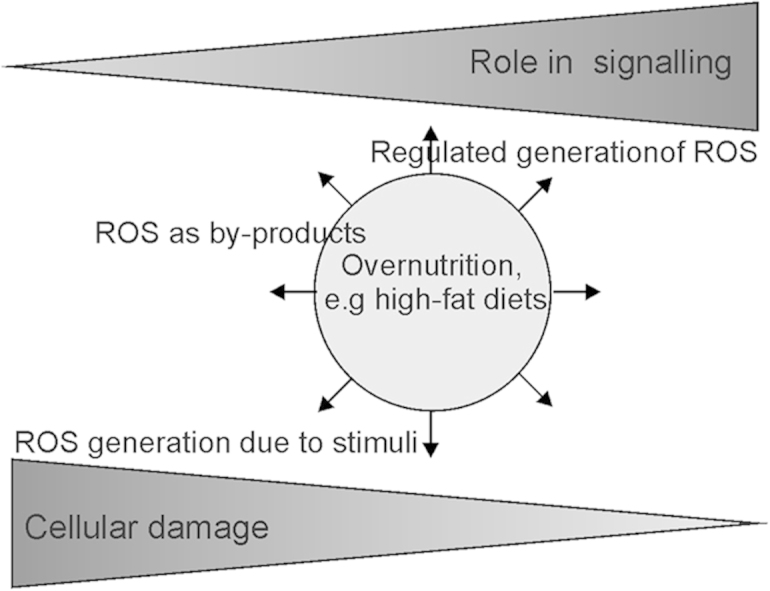

Fig. 2.

Interrelation between ROS in signaling and cell damage. ROS generated in cells by specific action of various enzymes appear to have a more critical role in signaling than ROS generated as by-products of intracellular processes or due to external toxic stimuli. ETC, electron transport chain. PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; KGDH, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase.

It appears that mitochondrial DNA is more susceptible to DNA damage than nuclear DNA since it lacks histones, has only a limited repair capacity, and is ultimately exposed to mitochondrial ROS [60]. In particular the displacement loop (D-loop) in mitochondrial DNA is known as mutational hotspot and associated with hepatocellular carcinoma [61], ovarian cancer [62], breast cancer [63], colorectal cancer [64] and melanoma [65].

Moreover, ROS can also influence epigenetic modifications (for review see [66]). For example, ROS can affect DNA methylation [67] by downregulating the expression of O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase and MLH1 (mutL homolog 1) [5]. In addition, it has been speculated that oxidative stress may also be involved in the oxidation of 5-methylcytosines to 5-hydroxy-methylcytosine [68]. Moreover, ROS-mediated formation of 8-oxodG adjacent to a cytosine may prevent methylation of the latter [69].

3. ROS-dependent regulation of signaling pathways

3.1. Kinase signaling and ROS

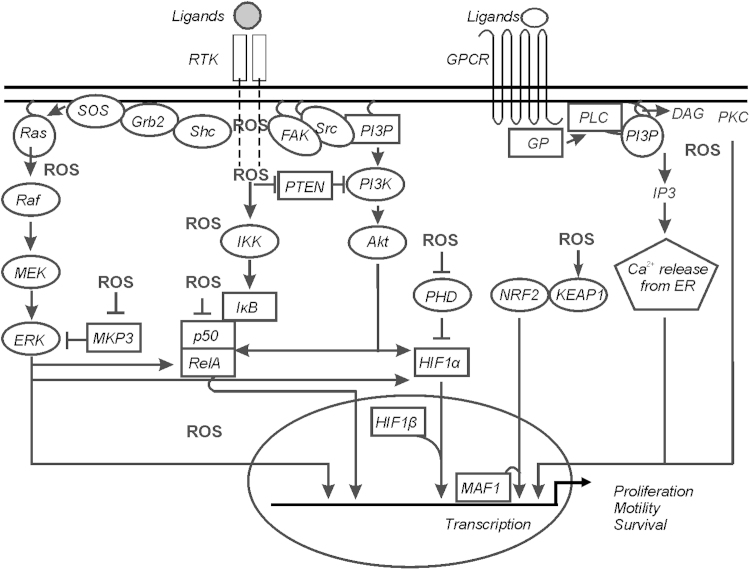

The action of ROS in various signaling networks is connected to their physiological role but also to diseases [70–73]. Various stimuli, among them nutrients like fatty acids, growth factors, hormones, coagulation factors, cytokines, and hypoxia were shown to act at least partially via regulated ROS generation (Fig. 2). Thus, aberrant generation or even degradation of ROS may limit the signaling function of these stimuli often affecting the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and/or phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K)/Akt cascades. ROS also affect pathways like protein kinase C (PKC), Wnt/β-catenin, Hedgehog, Notch [71, 74–76] in several ways [77], and many excellent reviews have covered the details [78,79]. We will thus concentrate only on some principles of the best studied so far.

3.2. MAPK signaling

ROS are known to be able to activate the ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) and JNK (c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase) MAPK cascades. Thereby they are supposed to cause autophosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or PDGFR in a ligand-dependent manner [80]. In addition, oxidative modification of Ras, a major component of the ERK1/2 cascade, at Cys118 [81] inhibits GDP/GTP exchange, and activates Ras and the whole cascade. Since MEK1/2 (MAPK/ERK kinase 1/2) inhibitors can suppress ROS-mediated ERK1/2 activation [82] ROS might act indirectly at the level of MEK1/2 or by antagonizing phosphatases (see below) like mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase (MKP3) [83] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

ROS-regulated signaling pathways. Simplified diagram representing major ROS regulated signaling pathways. ROS can influence the pathways either positively or negatively; see text for further explanations. ROS necessary for regulation of signaling pathways are mostly generated through specific enzymatic reactions as well as due to the changes in cellular metabolic activity leading to altered ROS production.

DAG, diacylglycerol; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; GP, G-protein; GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor; Grb2, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α; IκB, inhibitor of NF-κB; IKK, IκB kinase; MEK, MAPK/ERK kinase; MKP3, mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase phosphatase/dual specificity protein phosphatase-6; PHD, prolyl hydroxylase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases; PI3P, phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate; PKB/Akt, protein kinase B; PKC, protein kinase C; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10; Raf, ras attachement factor; Ras, Rat sarcoma; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; SOS, son of sevenless; Shc, SHC-transforming protein; Src, sarcoma.

ETC, electron transport chain; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NOX, NADPH oxidase subunit; PKC, protein kinase C; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

3.3. PI3K/Akt signaling

In addition to MAPK pathway activation, growth factor protein tyrosine kinase receptors including EGFR or PDGFR are also known to stimulate the protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) pathway [84]; ROS, especially H2O2 were found to activate PKB/Akt. In addition, the tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10), a counter regulator of PKB/Akt activation was found to be inactivated by ROS-dependent oxidation of Cys124 [85] thus enhancing PKB/Akt activation. Moreover, loss of PTEN also causes depletion of antioxidant enzymes [86] (Fig. 3).

3.4. PKC signaling

Three major PKC subfamilies are distinguished; (i) conventional PKC isoforms (cPKCs; α, with alternatively spliced βI/βII isoforms, and γ); (ii) the so called novel PKCs (nPKCs, with isoforms δ, θ, ε, and η), and (iii) atypical PKCs (aPKC; with isoforms Mζ, and ι/λ). The cPKCs require diacylglycerol and calcium for their activity while nPKCs can be activated by diacylglycerol independent of calcium; aPKCs do neither require calcium nor diacylglycerol. All are potentially susceptible to redox modifications due to their content in cysteine residues. Indeed, some proteinkinase C (PKC) isoforms like α, βI, and γ of cPKC, δ and ɛ of nPKC, and Mζ of aPKC, were activated upon treatment of cells with H2O2 [87] and further evidence points to ROS-dependent changes in a conserved cysteine-rich region in PKCα binding diacylglycerol [88]. However, it appeared that the redox-dependent activation of PKC can also be communicated in an indirect manner. In fact, the activation of PKCδ by H2O2 was not mediated by cysteine modification. Interestingly, the H2O2-dependent increase in PKCδ activity was caused by the tyrosine kinase Lck (a member of the Src family) which phosphorylated a tyrosine residue between the regulatory and catalytic domain [89]. Overall, the existence of various PKC isoforms with the option of a direct or indirect redox-dependent regulation adds another layer of complexity to the understanding of PKC regulation. This may in particular be important for those PKCs involved in metabolic regulation; in particular isoform θ in skeletal muscle and δ in liver can be activated by fatty acid metabolites such as fatty acyl CoA and diacylglycerol. As a consequence this can lead to inhibitory serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrates and an attenuation of insulin signaling [90] (Fig. 3).

3.5. Protein tyrosine phosphatases

Oxidation of catalytic cysteine residues and inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTP) is another ROS-dependent regulatory mechanism of action [91]. Extracellular ligand-stimulated ROS and signal-independent ROS production can cause PTP oxidation. In addition to classical PTPs dephosphorylating phosphotyrosine, also dual-specificity phosphatases like MAPK phosphatases can be inactivated by ROS-dependent oxidation [91] (Fig. 3).

4. Transcription factors and ROS

Transcription factors are among the ROS targets which can positively or negatively respond to nutrients by changing gene expression. Thereby the transcription factors nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor-2 (Nrf2), as well as hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and hypoxia-inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) appear to integrate the responses to different primary stimuli at the level of ROS signaling. [92,93] (Fig. 3). Activation/inhibition of these transcription factors can be crucial for adaptation, survival and progression of diseases like inflammation, type II diabetes, or cancer.

4.1. NF-κB signaling

The activation of NF-κB is closely linked with ROS generation during inflammation and obesity [94]. ROS were found to mediate inhibitor of NF-κBα (IκBα) kinase (IKKα and IKKβ) phosphorylation and release of free NF-κB dimers [95]. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), a bona fide NF-κB activator, was shown to mediate a redox-dependent activation of protein kinase A [96] which subsequently phosphorylated Ser276 on RelA (v-rel avian reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A). By contrast, the NF-κB member p50 was found to have reduced DNA binding activity when oxidized at Cys62 [97,98].

4.2. Nrf2 signaling

The Nrf2 and its partner Keap1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein (1) are considered as the major transcriptional regulators in the response and defense against oxidative stress [99,100]. The regulation of this dimer is primarily achieved by the sulfhydryl groups within Keap1 which act as sensors for electrophiles and oxidants [101]. In the absence of ROS binding of Keap1 promotes proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. In the presence of ROS, cysteine residues in Keap1, with Cys151 being the most critical, become oxidized leading to a conformational change of Keap1, which prevents its binding to Nrf2. In addition to oxidation, ROS can contribute to dephosphorylation of Keap1 at Tyr141 which contributes to Keap1 degradation [102]. As an overall consequence, Nrf2 is no longer degraded and can be transported to the nucleus. Moreover, oxidation of Cys183 in Nrf2 inhibits binding of the nuclear export protein CRM1 and thus promotes nuclear presence. In the nucleus, Nrf2 heterodimerizes with a small Maf protein to activate genes of the antioxidant response such as NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1, glutathione S-transferases, cysteine-glutamate exchange transporter, and multidrug resistance-associated protein.

Interestingly, Nrf2 activating substances like quercetin, genistein, curcumin and sulforaphane are often components of plants, fruits and vegetables; therapeutics such as oltipraz, auranofin and acetaminophen; environmental agents like paraquat, and metals as well as endogenous substances like hydrogen peroxide, NO, or 4-hydroxynonenal also activate Nrf2 signaling [103]. This somehow may imply that an activation of the Nrf2 pathway may be of therapeutical benefit. However, Keap1 knockout mice die shortly after birth. This finding and the rescue of this lethal phenotype in Keap1/Nrf2 double knockout mice [104] suggests that excessive Nrf2 activity may be detrimental for normal life. Indeed, this was supported by a study showing that constitutive activation of the Nrf2 pathway was beneficial for tumor survival [105].

4.3. HIFα signaling

ROS play an important role in HIF signaling (for review see [106]). Both HIF-1α and HIF-2α can be modified by ROS in a direct and indirect manner. Direct regulation requires presence of redox factor-1 (Ref-1) and affects transactivation of HIF-1α at Cys800 and of HIF-2α at Cys848 [107] as well as recruitment of coactivators such as steroid receptor coactivator-1 and transcription intermediary factor 2. Another direct redox effect is oxidation of the Cys present in the DNA-binding domain of HIF-2α, but not HIF-1α [108]. The indirect effects of ROS are mediated via regulation of prolyl hydroxylases (PHD), asparagine hydroxylases, redox-sensitive kinases, and phosphatases (for review see [3,109]). The PHDs hydroxylate HIF-1α and HIF-2α at critical proline residues thereby inducing HIF degradation under normoxia. The PHDs belong to a family of oxygen, Fe2+, 2-oxoglutarate, and ascorbate dependent dioxygenases (reviewed by [110]) which need a radical cycling system to regenerate the iron after each catalytic cycle [111]. Even though ascorbate is a key agent in the regeneration of iron, glutathione could substitute it in mice deficient in vitamin C synthesis, pointing to the importance of thiol oxidation/reduction cycles. In line, a pair of cysteine residues in one of the PHDs was described to modulate its redox sensitivity [112], again highlighting the possible involvement of thiol oxidation in regulating PHD activity, though in endothelial cells subjected to hypoxia, no variation in PHD cysteine oxidation was observed [113].

Both, HIF-1α and HIF-2α could be prevented from hydroxylation and degradation by increasing ROS generation from ER-localized NOX4 or addition of hydrogen peroxide to cells [114]. Moreover, ROS generated at the Qo site of the mitochondrial complex III affected HIF-1α and HIF-2α regulation [115,116]. Thereby mitochondrial ROS seemed to act upstream of prolyl hydroxylases in regulating HIF-1α and HIF-2α [117]. From the ROS formed, hydrogen peroxide seems to be of major importance for HIF regulation since overexpression of glutathione peroxidase or catalase, but not superoxide dismutase 1 or 2, prevented the hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α [115,116,118]. Together, ROS appear to constitute an important link for HIF regulation especially under certain metabolic regimes or diseases like cancer which are associated with altered mitochondrial activity [119].

In addition, HIFα signaling is known to undergo a crosstalk with both PI3K/Akt and MAPK cascades where ROS and NOX enzymes act as activators (reviewed by [120]). In line, antioxidants or NOX inhibitors blocked signaling via PI3K/Akt to HIF-1α [121]. In addition, a number of ROS inducing substances like angiotensin-II [122], prostaglandin E2 [123], shock waves [124], thrombin [121] or chromium (VI) [125] contribute to HIF-1α induction via ERK1/2 which also can phosphorylate HIF-1α [120]. Further, p38 MAPKs and the p38 upstream kinases MKK3 and MKK6 [126] were shown to be involved in the induction of HIF-1α by thrombin [121] and chromium (VI) [125]. In addition, these NADPH oxidases activating substances can also induce HIF-1α mRNA levels in several cell types [127–130]. In line, HIF-1α is a direct target gene of NFκB [131–135], and ROS derived from NOXes or direct application of H2O2 regulates NFκB–dependent HIF-1α transcription [132,136,137].

Taken together, ROS are important regulators of the HIF system and the crosstalk between ROS and HIF is an important pathophysiological link for a wide variety of disorders.

5. Hypoxia and ROS, a paradoxical and complex relationship

Paradoxically an increased availability of lipids and carbohydrates which is typical for a Western diet will also increase the demand on energy synthesis in form of ATP; i.e provision of these substances will activate usage of the mitochondrial electron transport chain and oxygen [138]. As a result of an acute hypoxic event a superoxide burst can occur [139]; however, hypoxia per se seems to affect ROS production with subsequent consequences for metabolic activity. In addition to mitochondria [119], several other sources have been proposed to be involved in the modulation of ROS levels under hypoxia, such as NADPH oxidases [140], or xanthine oxidase [141].

The variability of ROS production in response to changes in the ambient oxygen partial pressure has been linked with the activation of the HIF α-subunits. Although controversial data exist, there is evidence for a feedback regulation between ROS production and the HIF pathway. However, it appears that the molecular links between ROS, the complexes involved in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), and responses to hypoxia through the HIF pathway are complex, less direct and may involve cell specific factors [142,143]. This is indicated by the fact that most of the interventions (if not all) on OXPHOS complexes alter not only ROS production but also other activities, especially oxygen consumption, oxygen redistribution [144], or metabolites taking part in the HIF-α degrading PHD reaction such as 2-oxoglutarate or succinate (see above). In addition to this, several molecular approaches including overexpression of antioxidant enzymes showed a link between HIF activation and ROS formation which was independent of the cellular oxygen consumption [115–118].

Vice versa, adaptation to hypoxia through the HIF pathway has also an effect on ROS production. Both, NOX2 and NOX4 NADPH oxidases are HIF1 target genes [114,145] and are involved in maintaining angiogenesis, cellular proliferation, and hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension [114], as well as in metabolic diseases [146,147]. In mitochondria, several HIF-dependent mechanisms have been described that actively contribute to reduce OXPHOS activity under hypoxia and which have been shown (in more or less detail) to reduce mitochondrial ROS production: reduction of pyruvate entry into the TCA cycle through enhanced expression of PDK1 [148,149], PDK3 [150] or PDK4 [151,152], reduction of complex I activity through upregulation of NDUFA4L2 expression [153], and reduction of the activity of iron-sulfur clusters-containing proteins (among them OXPHOS complexes) by enhanced expression of miR-210, which represses the iron-sulfur cluster assembly proteins ISCU1/2 [154].

In addition, HIF-1α and HIF-2α are able to affect mitochondrial ROS production also in a negative manner. Thereby HIF-1 regulates the hypoxic switch from COX4-1 to COX4-2 in cytochrome c oxidase at complex IV, and the mitochondrial protease LON which degrades COX4-1 [155]. In line, HIF-1α-dependent upregulation of the tumor suppressor REDD1 decreases ROS production while loss of REDD1 increases mitochondrial ROS [156]. HIF-2α was found to be involved in the regulation of the SOD2 gene [157]. Together, these mechanisms are part of a negative feedback loop for regulation of HIF-1α and HIF-2α.

Another mechanism by which hypoxic responses can be mediated through ROS production is reversible protein cysteine oxidation. Indeed, the recent use of a redox proteomic method, by which reversibly oxidized protein cysteines are specifically labeled [158], has helped to identify a number of proteins specifically oxidized in cardiac mitochondria from mice subjected to ischemia/reperfusion or from endothelial cells subjected to acute hypoxia [113,159]. Thus, the identification of reversibly oxidized proteins by a fluorescent labeling and LC-MS/MS-based approach provides the option to explore more closely the links between acute or chronic adaptations to hypoxia and ROS generation.

Together, it is obvious that an intricate interplay between hypoxia and ROS production exists and that this involves feed-forward and feed-back mechanisms involving HIFs function. However, the detailed mechanisms, the timing of the responses as well as the cell-type specific factors involved in these regulations need still further investigations before they are completely understood.

6. Dietary fashion, ROS, and diseases

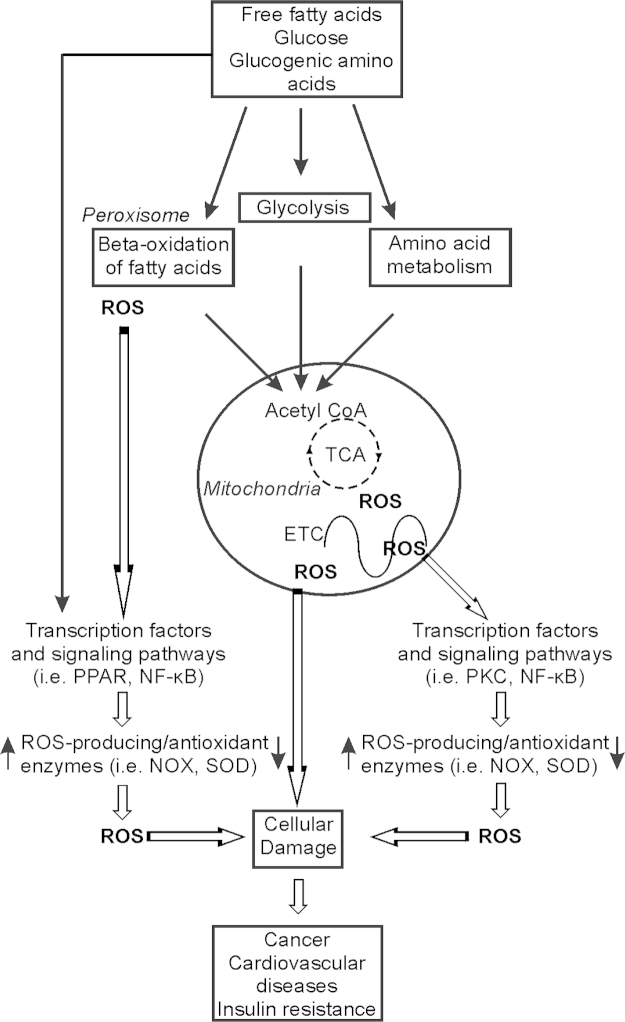

In Western societies, a significant part of the day is spent in the postprandial state. Postprandial oxidative stress is characterized by an increased susceptibility of the organism towards oxidative damage after consumption of a meal rich in lipids, proteins and/or carbohydrates (Fig.4). Evolution of dietary patterns and lifestyle in most developed countries support the evidence that there is a direct relationship between diet, lifestyle and risk of certain diseases including cancer; up to 35% of risk is estimated to be associated with diet [160]. The postprandial state is characterized by persistent substrate abundance in the circulation. Increased substrate availability (like glucose), leads to an increased insulin release and also to an increment in oxidative stress as, for example, a higher production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [161]. The permanent availability of oxidizable substrates at rest leads to an enhanced mitochondrial membrane potential which, in turn, leads to a diminished velocity in oxidative phosphorylation and, thus, a higher possibility for electrons to “leak” from the respiratory chain directly to molecular oxygen, resulting in ROS generation [162] (Fig. 4). In turn, the diminished substrate utilization is accompanied by an increment in NADH, in both the cytosol and in mitochondria. NAD+ and NADH values are kept relatively constant within a cell, and the ratio between them is considered to be a marker of the metabolic status [163]. As such, high levels of cellular nutrient metabolites result in ROS production and oxidative stress as well as the development and progression of diseases like obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD), type II diabetes, atherosclerosis or cancer which are increasing, rapidly reaching epidemic proportions.

Fig. 4.

Nutrients modulate ROS generation. Nutrients (free fatty acids, glucose, amino acids) stimulate ROS production by increasing the postprandial metabolic rate, especially in mitochondria. Further, nutrients affect ROS via signal cascades and transcription factors that regulate expression of antioxidant/ROS-generating enzymes.

In addition to the direct effect on ROS production, mainly via the ETC, although data on NADPH oxidases also exist, nutrients have long-term indirect effects on ROS levels via regulation of gene expression. Thereby peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR), liver X receptors, and sterol response element-binding proteins, contribute to fatty acid-induced transcription [164]. In particular PPARγ was found to promote elimination of ROS; in a murine model of type 2 diabetes, PPARγ activation exerted an antioxidant effect in vivo [165] and decreased expression of PPARγ in morbidly obese persons was associated with the decrease of Cu/ZnSOD and glutaredoxin activities and an increase in the concentration of free fatty acids after a fat meal [166]. These features as well as the link between PPARγ, HIF-1α and activated fatty acid uptake and glycerolipid synthesis seem to be important for cardiac contractile dysfunction. Indeed, deletion of HIF-1α in the heart of mice prevented hypertrophy-induced PPARγ activation, metabolic reprogramming, and contractile dysfunction [167]. In addition, fatty acids and glucose may modify the activity of transcription factors like NF-κB, and HIF-1α [74,164] which have antioxidant as well as ROS-generating enzyme coding genes as targets. Therefore, transcription factors like NF-κB or HIF-1 can respond to a macronutrient-dependent burst in ROS as well as to the macronutrient-mediated regulation of intracellular signaling pathways like PKC or PKB. Overall, the short-term action of macronutrients may increase ROS, but they may also cause increased ROS scavenging via their long-term action on transcription factors.

6.1. Diets and oxidative stress

High-fat diets (HFDs) typically contain about 32–60% of calories from fat and are commonly used to induce obesity in rodents [168,169]. A HFD is associated with body weight increase, fat deposition throughout various organs, a marked insulin resistance and development of a hypoxic status in the fat depositing organs. Before a significant peripheral fat deposition occurs, HFDs typically increase liver fat levels as well as hepatic insulin resistance, elevation of ROS and oxidative stress [170]. In addition, the hypoxic status becomes evident already after three days of feeding a HFD in white adipocytes. Subsequently, HIF-1α induction contributes to an off-set of the chronic adipose tissue inflammatory response [171]. Importantly, the source of dietary fat can modify the “phenotype”; e.g. in comparison to fat from butter, polyunsaturated fats present in olive and fish oil increase liver fat oxidation, reduce liver triglyceride accumulation and liver cholesterol levels, respectively [172] as well as induce expression of pro-inflammatory genes [173].

An excess intake of refined carbohydrates is associated with increased weight gain, hypertriglyceridemia, ROS production and insulin resistance in humans and animal models [174,175]. Usually, rodent chow diets contain only 4% sucrose and less than 0.5% of free fructose with most carbohydrates as both digestible starch and non-digestible fiber from grain sources. In contrast, low-fat purified diets can contain higher levels of sucrose and this will depend heavily on the formula being used. It is possible to modify purified diets by manipulating only the carbohydrates while the essential nutrients remain at recommended levels to promote a metabolic syndrome and to have different oxidative stress levels.

A methionine and choline-deficient (MCD) diet rapidly induces hepatic macrovesicular steatosis in rodents and leads to inflammation, fibrosis and cancer [176,177]. The MCD diet also contains sucrose, which induces de novo lipogenesis and triglyceride synthesis. Despite inducing the same overall level of hepatic fat accumulation, fructose was more effective than glucose in inducing hepatocellular injury in mice fed MCD diets for 21 days [178]. A choline-deficient diet alone induces only steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis within 10 weeks [179,180], but not a marked hepatitis, cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. A choline-deficient l-amino acid-defined diet leads to the development of typical non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), with lobular inflammation and fibrosis, a basis on which further hepatocarcinoma develops [181].

6.2. Metabolic reprogramming and ROS generation

Several studies are consistent with the idea that an increased caloric intake and/or obesity are associated with a pro-oxidant environment and increased oxidative damage [8–12] (Fig. 5). In line, both protein carbonylation and lipid peroxidation were increased in white adipose tissue and liver of animals with high-nutrient feeding induced obesity [182]. Increased ROS production was shown in mitochondria isolated from skeletal muscle, kidney, liver and adipose tissue from obese HFD fed animals [183–186]. In addition, NADPH oxidases have also been described to contribute to elevated ROS levels and to be upregulated in the liver in several animal models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [187,188] where animals were treated with an “high-fat” or “hypercholesterolemic” diet. Interestingly, female mice lacking the NADPH oxidase subunit p47phox are protected against high fat diet induced obesity [189]. Similar results have been obtained in NOX2-deficient mice [190] while NOX4 deficient mice were reported to be more obese and to have hepatic steatosis and whole body insulin resistance [191]. The role of NOX2 in insulin resistance was also corroborated in skeletal muscle. Here, a long-term HFD increased NOX2 expression, superoxide production, and impaired insulin signaling in skeletal muscle of wild-type mice; these effects were not occurring in NOX2-deficient mice. Cell culture experiments with C2C12 myotubes revealed a key role for H2O2 in mediating insulin resistance since down-regulation of NOX2 by shRNA prevented insulin resistance induced by high glucose or palmitate [192].

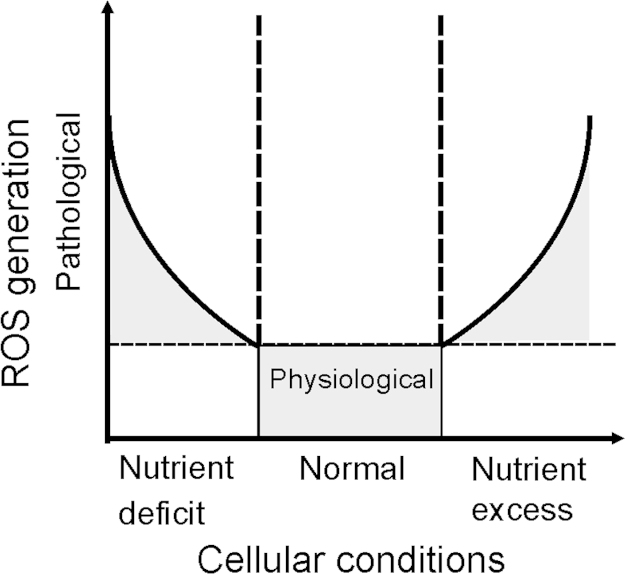

Fig. 5.

ROS generation and nutrient availability. Under nutrient-deficient conditions, as well as in the presence of nutrient excess ROS formation is above the physiological threshold. As such, these conditions may be considered as pathological situations, with abnormally high ROS generation.

Further, increased mitochondrial ROS were found to be involved in short-term HFD-induced insulin resistance in white adipose tissue. Consuming a high-fat diet for one week impaired insulin signaling, increased c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase phosphorylation and mitochondrial ROS formation. Overexpression of human catalase in the mitochondria of these mice attenuated mitochondrial ROS formation, inflammation, and maintained insulin signaling. Thus, elevated mitochondrial ROS formation can contribute to HFD-induced insulin resistance in white adipose tissue [193]. Moreover, HIF transcription factors were shown to be induced by NOX4-derived ROS [132,194] and lipid load [106,195]. Thus, HIFs and NOXes appear to be involved in insulin resistance, metabolic dysfunction and inflammation [171,196,197] and thus might play an important role in the concert of redox related processes promoting the development of steatohepatitis, obesity and type II diabetes, and aging-related diseases. Aging tissues exhibit higher rates of ROS generation, genetic instability, and inflammation and in some cases telomere shortening which is accelerated during diabetes [198,199].

Conditions of reduced glucose supply activate metabolic reprogramming that switches cells to metabolize fatty acids and amino acids through the TCA cycle and OXPHOS; this elevates the risk of mitochondrial oxidative damage, when compared only to the metabolization of glucose via glycolysis (Fig. 5). Exposure of cells in culture to free fatty acids increases ROS, suggesting that an elevated concentration of fatty acids in the circulation may provide an additional source of excess OXPHOS substrates through increased fatty acid oxidation [200]. However, studies performed with obese animals that develop diabetes, have shown a state of metabolic inefficiency where an increase in cardiac fatty acid utilization is associated with enhanced mitochondrial oxygen consumption but a lower cardiac contractile capacity [201–203]. Moreover, these hearts exhibit limited ATP generation associated with fatty acid-induced mitochondrial uncoupling and are unable to modulate their substrate utilization in response to insulin and fatty acid supply [201,204]. These findings suggest that mitochondrial dysfunction in response to diets may arise from lipotoxicity or oxidative stress [205,206] rather than from changes in glucose concentrations [204,206]. This view is supported by a study indicating that ROS are also involved in obesity-induced autophagy. Interestingly HFD fed transgenic mice with cardiac overexpression of catalase did not display ROS production and showed suppressed autophagy in the heart. In addition, the HFD compromised myocardial geometry and function like hypertrophy, enlarged left ventricular end systolic and diastolic diameters, fractional shortening, cardiomyocyte contractile capacity and intracellular Ca2+ were attenuated by catalase. On the molecular level these HFD-mediated effects in the heart seemed to be transmitted by an IKKβ-AMPK-dependent pathway which could be inhibited by catalase [207].

By contrast, the metabolism in cancer cells is a strong example how glucose deprivation and altered mitochondrial function contribute to massive ROS production [208]. Energy production in cancer cells is abnormally dependent on glycolysis classically best known the “Warburg effect”. Moreover, the rapid proliferating status dictates an increased biosynthesis which is dependent on the availability of building blocks and reducing equivalents [209]. Therefore, cancer cells may be considered to be in a perpetually “hungry” state. NOX1 seems to be involved in regulation of the Warburg effect and metabolic remodeling of hepatic tumor cells towards a sustained production of building blocks required to maintain a high proliferative rate [210].

Moreover, cancer cells often proliferate in a hypoxic milieu, where the adaptation is largely dependent on HIF transcription factors regulated by NOX, and the transcriptional activation of genes involved in various metabolic pathways, among them carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolism. Thereby, the role of hypoxia and HIFs, especially HIF-1 as regulator of carbohydrate metabolism is well established. In this respect, HIFs respond to enhanced levels of insulin [211–213] and regulate almost every gene which is involved in glucose uptake, glycogen synthesis, and glycolysis [142,214]. Reciprocally, gluconeogenesis in liver is reduced under hypoxia as indicated by the decreased expression of the key gluconeogenic enzyme PCK1 [215]. Moreover, lipid metabolism, in particular in liver, appears to be more regulated by HIF-2 [216]. In addition to the direct involvement of the HIF proteins as powerful regulators of metabolism, recent findings indicated a cross-talk between the insulin signaling pathway and hypoxia signaling at the level of the HIF-regulating proline hydroxylases in liver. In particular PHD3 was found to have a key role since its acute deletion improved insulin sensitivity and ameliorated diabetes by specifically stabilizing HIF-2α [217].

Moreover, a vast majority of endogenously derived fatty acids are synthesized in the cytosol from acetyl-CoA through a large polyfunctional fatty acid synthetase encoded by the FASN gene. Both the cytosolic form of acetyl-CoA synthase and FASN itself can be induced by hypoxia [218]. However, hypoxic induction of FASN appears to be an indirect HIF effect involving first HIF-dependent up-regulation of SREBP1 and an action of SREBP1 on the promoter of FASN [218]. Further, hypoxia and the Ras regulated MAPK pathway were also shown to regulate elongation and desaturation of fatty acids for lipogenesis [219]. In addition to the role of hypoxia/HIF-1-dependent regulation of lipid metabolism, there exist also a number of hypoxia mediated, but HIF1α-independent alterations of lipid metabolites and associated enzymes. For example, a recent metabolomics approach showed that enzymatic steps in fatty acid synthesis and the de novo synthesis of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine were modified in a HIF1α-dependent fashion whereas palmitate, stearate, phospholipase D3 and platelet activating factor 16 were regulated in a HIF-independent manner [220]. Overall, these findings help to understand why an increased lipid content is a common feature of hypoxic cancer cells [142]

Although stabilization of HIF-1α contributes to a decrease in oxidative phosphorylation, and an initial increase in ROS production, likely via NOX4, it also initiates a later counteracting adaptive response e.g. by switching complex IV subunits or by increasing the mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase content [143]. These features may be important for the survival of metastatic cancer cells since it was described that colonization of lungs with cancer cells is dependent on reduced ROS due to HIF-1-mediated metabolic reprogramming [221].

In line, the up-regulation of the antioxidant capacity in some subsets of cancer stem cells appears to be associated with resistance to therapy [222]. This makes exogenous agents, which are able to modulate the susceptibility of cancer cells to oxidative insults, interesting for anticancer strategies [223] and may, at least in part, explain why antioxidant supplementation in cancer patients is not necessarily beneficial (see below).

Recent findings from experiments where the mitochondria targeted redox cycler mitoquinone was able to induce an autophagic growth arrest in breast cancer cells associated with enhanced ROS levels and the initiation of an antioxidant response underline this. Interestingly, a further knockdown of Nrf2 in these cells potentiated the autophagy [224]. In line, more recent data indicate that high ROS can cause autophagy, but that autophagy is able to trigger an antioxidant feedback response by linking autophagy related gene 7 (Atg7) with Keap1 and Nrf2 [225]. Overall, this is in line with findings that a forced activation of Nrf2 has a pro-carcinogenic function (see above) and why antioxidants are not simply protective against cancer (see below).

Moreover, inactivating mutations in genes that promote autophagy have been described in several human cancers, as well as activation of genes that block autophagy [226]. Hyperactivation of the Ser/Thr kinase mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) has been shown to promote breast cancer progression through increasing autophagy [227] and aberrant mTORC1 signaling has been frequently detected among common human cancers [228]. Thereby mTORC1 integrates the activation of kinase complexes like receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), the PI3K, and the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways which are ROS sensitive and dictates the balance between the energetic and anabolic demands of rapidly proliferating cancer cells [229]; hence linking autophagy with ROS, cancer and nutrition.

6.3. Antioxidative therapeutic strategies: rather harmful than beneficial?

The association of ROS with various diseases like atherosclerosis, type II diabetes or cancer is known for more than three decades [5,6,71,230] and accordingly this led to the believe that an antioxidant supplementation would have beneficial therapeutic effects. Indeed, the first observations were promising and an ‘antioxidant hype’ emerged throughout the world. As a result, high doses of antioxidants were examined in hundreds of studies among them about a dozen of large randomized trials where various combinations of the best known antioxidants except polyphenols (so called ‘traditional antioxidants’) were included [231]. More than 10 large-scale trials have been completed (for review see [232]). The outcome was enigmatic. There was no corroboration of the data derived from non-human models as well as from observational epidemiologic studies. In particular, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials including tens of thousands subjects found no overall association between the consumption of antioxidant supplements and cancer risk [233] (for detailed review see [232]). This ‘antioxidant paradox’ [234] is not only limited to cancer but also reported for type II diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [235,236].

So far it is not known why the antioxidants did not exert the expected protective effects. The wrong type, dose, combination, and/or duration of exposure may explain some but not all. Indeed, in almost all large-scale trials high doses of each antioxidant were used either alone or in limited combinations. In addition, mechanisms of actions have been neglected; some antioxidants including vitamin E, vitamin C, and quercetin, can act as prooxidants at high concentrations. Indeed, meta-analyses of the vitamin E dose and total mortality indicated that vitamin E at high doses ≥400 IU/day) may be associated with increased mortality due to the prooxidant effects of vitamin E at these concentrations [237]. Moreover, β–carotene can act as prooxidant when given to smokers [238,239]. In line, quercetin at concentrations in the range of 1–40 µM reacts with ROS and chelates metal ions whereas at concentrations higher than 40 µM it increases oxidative stress [240]. Thus, antioxidant therapy may be improved if patients would be tested for subclinical deficiencies of antioxidants before such a therapy is initiated. In addition, the large clinical trials did not test for compliance like the EPIC Norfolk clinical trial in which certain antioxidant levels were measured in plasma and where significant improvement of various parameters could be reported. For example, parental administration of vitamin C was highly beneficial in many different disease conditions [241].

However, the beneficial effects of antioxidant-rich food at least with respect to cancer are widely reported [242–244]; but these benefits are achieved by the diet itself and not by supplementation [245]. Moreover, the dietary intake involves low doses of various antioxidants and not high doses of a single antioxidant. In line, while high doses of single antioxidants were shown to be harmful in smokers, two antioxidant-rich diets were found to be safe in a randomised controlled trial in male smokers [246]. Overall, this suggests that antioxidant therapies are not hopeless but to find an optimal way more research on ROS, antioxidants and nutrition in line with large multicenter trials are necessary.

7. Conclusion

ROS have likely evolved together with the appearance of oxygen on earth and the evolution of aerobic living cells. At the same time aerobic living cells developed systems allowing to use ROS in signaling and to protect themselves from their harmful effects. Within these systems components need to be maintained and provision of certain substances through the diet is a prerequisite. Although the human genome seems to be quite stable for the last ten thousand years (spontaneous mutation rate is appr. 0.5% per million years [247]), dietary fashion, food amount and composition has changed within the last 60–100 years; at least in the Western world. In addition to the increase in the caloric intake, also the decreased energy expenditure as well as alcoholism and smoking contribute to generation of more ROS than needed. As a consequence the antioxidant capability is confronted with various problems and not always able to maintain redox homeostasis, which is, at least in part, associated with the occurrence of several chronic diseases like adiposity, atherosclerosis, type II diabetes, and cancer. In addition, the little or no benefit evidence from the large scale studies with antioxidant supplementation demands to further improve the knowledge about the interconnection of ROS with nutrition and diseases indicating that the associated health problems are not yet solved.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful and apologize to all researchers who contributed to the field and whose work could not be cited due to space limitations. This work was supported by grants from German Research Foundation (DFG-GO709/4-5), DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research), German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Acidox, Epiros), to AG. Work in the AMR lab was supported by grants from the Spanish Government (PI12/00875) and from the Fundación Domingo Martínez; AMR and PHA are supported by the I3SNS and FPU programs of the Spanish Government, respectively. Work in the TK lab was supported by grants from the Finnish Academy of Sciences, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, CIMO, and Biocenter Oulu. Some of the authors were supported by the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST Action BM1203/EU‐ROS).

References

- 1.Wood P.M. The potential diagram for oxygen at pH 7. Biochem. J. 1988;253:287–289. doi: 10.1042/bj2530287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winterbourn C.C. Reconciling the chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:278–286. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kietzmann T., Gorlach A. Reactive oxygen species in the control of hypoxia-inducible factor-mediated gene expression. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2005;16:474–486. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceriello A., Motz E. Is oxidative stress the pathogenic mechanism underlying insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease? The common soil hypothesis revisited. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:816–823. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000122852.22604.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziech D., Franco R., Pappa A., Panayiotidis M.I. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)—induced genetic and epigenetic alterations in human carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. 2011;711:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta S.C., Hevia D., Patchva S., Park B., Koh W. Upsides and downsides of reactive oxygen species for cancer: the roles of reactive oxygen species in tumorigenesis, prevention, and therapy. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012;16:1295–1322. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimova E.Y., Samoylenko A., Kietzmann T. Oxidative stress and hypoxia: implications for plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2004;6:777–791. doi: 10.1089/1523086041361596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sankhla M., Sharma T.K., Mathur K., Rathor J.S., Butolia V. Relationship of oxidative stress with obesity and its role in obesity induced metabolic syndrome. Clin. Lab. 2012;58:385–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chrysohoou C., Panagiotakos D.B., Pitsavos C., Skoumas J., Krinos X. Long-term fish consumption is associated with protection against arrhythmia in healthy persons in a Mediterranean region--the ATTICA study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;85:1385–1391. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houstis N., Rosen E.D., Lander E.S. Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance. Nature. 2006;440:944–948. doi: 10.1038/nature04634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furukawa S., Fujita T., Shimabukuro M., Iwaki M., Yamada Y. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:1752–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts C.K., Sindhu K.K. Oxidative stress and metabolic syndrome. Life Sci. 2009;84:705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaludercic N., Deshwal S., Di Lisa F. Reactive oxygen species and redox compartmentalization. Front. Physiol. 2014;5:285. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ushio-Fukai M. Localizing NADPH oxidase-derived ROS. Sci. STKE. 2006;2006:re8. doi: 10.1126/stke.3492006re8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geiszt M., Leto T.L. The Nox family of NAD(P)H oxidases: host defense and beyond. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:51715–51718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babior B.M., Lambeth J.D., Nauseef W. The neutrophil NADPH oxidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;397:342–344. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Deken X., Wang D., Many M.C., Costagliola S., Libert F. Cloning of two human thyroid cDNAs encoding new members of the NADPH oxidase family. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:23227–23233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suh Y.A., Arnold R.S., Lassegue B., Shi J., Xu X. Cell transformation by the superoxide-generating oxidase Mox1. Nature. 1999;401:79–82. doi: 10.1038/43459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng G., Cao Z., Xu X., van Meir E.G., Lambeth J.D. Homologs of gp91phox: cloning and tissue expression of Nox3, Nox4, and Nox5. Gene. 2001;269:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bedard K., Krause K.H. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rokutan K., Kawahara T., Kuwano Y., Tominaga K., Nishida K. Nox enzymes and oxidative stress in the immunopathology of the gastrointestinal tract. Semin. Immunopathol. 2008;30:315–327. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui X.L., Brockman D., Campos B., Myatt L. Expression of NADPH oxidase isoform 1 (Nox1) in human placenta: involvement in preeclampsia. Placenta. 2006;27:422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uchizono Y., Takeya R., Iwase M., Sasaki N., Oku M. Expression of isoforms of NADPH oxidase components in rat pancreatic islets. Life Sci. 2006;80:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller F.J., Jr., Filali M., Huss G.J., Stanic B., Chamseddine A. Cytokine activation of nuclear factor kappa B in vascular smooth muscle cells requires signaling endosomes containing Nox1 and ClC-3. Circ. Res. 2007;101:663–671. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.151076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hilenski L.L., Clempus R.E., Quinn M.T., Lambeth J.D., Griendling K.K. Distinct subcellular localizations of Nox1 and Nox4 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:677–683. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000112024.13727.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petry A., Weitnauer M., Gorlach A. Receptor activation of NADPH oxidases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010;13:467–487. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geiszt M., Kopp J.B., Varnai P., Leto T.L. Identification of renox, an NAD(P)H oxidase in kidney. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:8010–8014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130135897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmona-Cuenca I., Herrera B., Ventura J.J., Roncero C., Fernandez M. EGF blocks NADPH oxidase activation by TGF-beta in fetal rat hepatocytes, impairing oxidative stress, and cell death. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006;207:322–330. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ago T., Kitazono T., Ooboshi H., Iyama T., Han Y.H. Nox4 as the major catalytic component of an endothelial NAD(P)H oxidase. Circulation. 2004;109:227–233. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105680.92873.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cucoranu I., Clempus R., Dikalova A., Phelan P.J., Ariyan S. NAD(P)H oxidase 4 mediates transforming growth factor-beta1-induced differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Circ. Res. 2005;97:900–907. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000187457.24338.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petry A., Djordjevic T., Weitnauer M., Kietzmann T., Hess J. NOX2 and NOX4 mediate proliferative response in endothelial cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006;8:1473–1484. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown D.I., Griendling K.K. Nox proteins in signal transduction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47:1239–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.BelAiba R.S., Djordjevic T., Petry A., Diemer K., Bonello S. NOX5 variants are functionally active in endothelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;42:446–459. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Deken X., Wang D., Dumont J.E., Miot F. Characterization of ThOX proteins as components of the thyroid H(2)O(2)-generating system. Exp. Cell Res. 2002;273:187–196. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischer H. Mechanisms and function of DUOX in epithelia of the lung. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:2453–2465. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ha E.M., Oh C.T., Bae Y.S., Lee W.J. A direct role for dual oxidase in Drosophila gut immunity. Science. 2005;310:847–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1117311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tirone F., Cox J.A. NADPH oxidase 5 (NOX5) interacts with and is regulated by calmodulin. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1202–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murphy M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brand M.D. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp. Gerontol. 2010;45:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vina J., Gambini J., Lopez-Grueso R., Abdelaziz K.M., Jove M. Females live longer than males: role of oxidative stress. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011;17:3959–3965. doi: 10.2174/138161211798764942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishikawa T., Edelstein D., Du X.L., Yamagishi S., Matsumura T. Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature. 2000;404:787–790. doi: 10.1038/35008121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cardoso A.R., Chausse B., da Cunha F.M., Luevano-Martinez L.A., Marazzi T.B. Mitochondrial compartmentalization of redox processes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;52:2201–2208. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quinlan C.L., Goncalves R.L., Hey-Mogensen M., Yadava N., Bunik V.I. The 2-oxoacid dehydrogenase complexes in mitochondria can produce superoxide/hydrogen peroxide at much higher rates than complex I. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:8312–8325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.545301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher-Wellman K.H., Gilliam L.A., Lin C.T., Cathey B.L., Lark D.S. Mitochondrial glutathione depletion reveals a novel role for the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex as a key H2O2-emitting source under conditions of nutrient overload. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;65:1201–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tretter L., Adam-Vizi V. Generation of reactive oxygen species in the reaction catalyzed by alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:7771–7778. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1842-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Starkov A.A., Fiskum G., Chinopoulos C., Lorenzo B.J., Browne S.E. Mitochondrial alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex generates reactive oxygen species. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:7779–7788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1899-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giorgio M., Migliaccio E., Orsini F., Paolucci D., Moroni M. Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell. 2005;122:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gorlach A., Klappa P., Kietzmann T. The endoplasmic reticulum: folding, calcium homeostasis, signaling, and redox control. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006;8:1391–1418. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Janiszewski M., Lopes L.R., Carmo A.O., Pedro M.A., Brandes R.P. Regulation of NAD(P)H oxidase by associated protein disulfide isomerase in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:40813–40819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509255200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Q., Berchner-Pfannschmidt U., Moller U., Brecht M., Wotzlaw C. A Fenton reaction at the endoplasmic reticulum is involved in the redox control of hypoxia-inducible gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4302–4307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400265101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nohl H., Gille L. The bifunctional activity of ubiquinone in lysosomal membranes. Biogerontology. 2002;3:125–131. doi: 10.1023/a:1015288220217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kurz T., Eaton J.W., Brunk U.T. Redox activity within the lysosomal compartment: implications for aging and apoptosis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010;13:511–523. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Antonenkov V.D., Grunau S., Ohlmeier S., Hiltunen J.K. Peroxisomes are oxidative organelles. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010;13:525–537. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schrader M., Fahimi H.D. Peroxisomes and oxidative stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1763:1755–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maehly A.C., Chance B. The assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Biochem. Anal. 1954;1:357–424. doi: 10.1002/9780470110171.ch14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wiseman H., Halliwell B. Damage to DNA by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: role in inflammatory disease and progression to cancer. Biochem. J. 1996;313(Pt 1):17–29. doi: 10.1042/bj3130017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marnett L.J. Oxy radicals, lipid peroxidation and DNA damage. Toxicology. 2002;181–182:219–222. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00448-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valko M., Rhodes C.J., Moncol J., Izakovic M., Mazur M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2006;160:1–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stadtman E.R. Role of oxidant species in aging. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004;11:1105–1112. doi: 10.2174/0929867043365341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carew J.S., Huang P. Mitochondrial defects in cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2002;1:9. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tamori A., Nishiguchi S., Nishikawa M., Kubo S., Koh N. Correlation between clinical characteristics and mitochondrial d-loop DNA mutations in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1063–1068. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1445-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu V.W., Shi H.H., Cheung A.N., Chiu P.M., Leung T.W. High incidence of somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in human ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5998–6001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tan D.J., Bai R.K., Wong L.J. Comprehensive scanning of somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:972–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lievre A., Chapusot C., Bouvier A.M., Zinzindohoue F., Piard F. Clinical value of mitochondrial mutations in colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:3517–3525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takeuchi H., Fujimoto A., Hoon D.S. Detection of mitochondrial DNA alterations in plasma of malignant melanoma patients. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1022:50–54. doi: 10.1196/annals.1318.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mikhed Y., Gorlach A., Knaus U.G., Daiber A. Redox regulation of genome stability by effects on gene expression, epigenetic pathways and DNA damage/repair. Redox Biol. 2015;5:275–289. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Franco R., Schoneveld O., Georgakilas A.G., Panayiotidis M.I. Oxidative stress, DNA methylation and carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chia N., Wang L., Lu X., Senut M.C., Brenner C. Hypothesis: environmental regulation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine by oxidative stress. Epigenetics. 2011;6:853–856. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.7.16461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Turk P.W., Laayoun A., Smith S.S., Weitzman S.A. DNA adduct 8-hydroxyl-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-hydroxyguanine) affects function of human DNA methyltransferase. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:1253–1255. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.5.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kapahi P., Boulton M.E., Kirkwood T.B. Positive correlation between mammalian life span and cellular resistance to stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;26:495–500. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vurusaner B., Poli G., Basaga H. Tumor suppressor genes and ROS: complex networks of interactions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;52:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morgan M.J., Liu Z.G. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Res. 2011;21:103–115. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kristal A.R., Arnold K.B., Neuhouser M.L., Goodman P., Platz E.A. Diet, supplement use, and prostate cancer risk: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010;172:566–577. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Comba A., Lin Y.H., Eynard A.R., Valentich M.A., Fernandez-Zapico M.E. Basic aspects of tumor cell fatty acid-regulated signaling and transcription factors. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30:325–342. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9308-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yao H., Ashihara E., Maekawa T. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in human cancers. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2011;15:873–887. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.577418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lauth M. RAS and Hedgehog—partners in crime. Front. Biosci. (Landmark edition) 2011;16:2259–2270. doi: 10.2741/3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ray P.D., Huang B.W., Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell. Signal. 2012;24:981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Badid N., Ahmed F.Z., Merzouk H., Belbraouet S., Mokhtari N. Oxidant/antioxidant status, lipids and hormonal profile in overweight women with breast cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2010;16:159–167. doi: 10.1007/s12253-009-9199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Basnet P., Skalko-Basnet N. Curcumin: an anti-inflammatory molecule from a curry spice on the path to cancer treatment. Molecules. 2011;16:4567–4598. doi: 10.3390/molecules16064567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Knebel A., Rahmsdorf H.J., Ullrich A., Herrlich P. Dephosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases as target of regulation by radiation, oxidants or alkylating agents. EMBO J. 1996;15:5314–5325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lander H.M., Hajjar D.P., Hempstead B.L., Mirza U.A., Chait B.T. A molecular redox switch on p21(ras). Structural basis for the nitric oxide-p21(ras) interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4323–4326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McCubrey J.A., Steelman L.S., Chappell W.H., Abrams S.L., Wong E.W. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell growth, malignant transformation and drug resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1773:1263–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chan D.W., Liu V.W., Tsao G.S., Yao K.M., Furukawa T. Loss of MKP3 mediated by oxidative stress enhances tumorigenicity and chemoresistance of ovarian cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1742–1750. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mehdi M.Z., Azar Z.M., Srivastava A.K. Role of receptor and nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases in H2O2-induced PKB and ERK1/2 signaling. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2007;47:1–10. doi: 10.1385/cbb:47:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee J., Giordano S., Zhang J. Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: cross-talk and redox signalling. Biochem. J. 2012;441:523–540. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huo Y.Y., Li G., Duan R.F., Gou Q., Fu C.L. PTEN deletion leads to deregulation of antioxidants and increased oxidative damage in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2008;44:1578–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Konishi H., Tanaka M., Takemura Y., Matsuzaki H., Ono Y. Activation of protein kinase C by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to H2O2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:11233–11237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kazanietz M.G. Targeting protein kinase C and “non-kinase” phorbol ester receptors: emerging concepts and therapeutic implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1754:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Konishi H., Yamauchi E., Taniguchi H., Yamamoto T., Matsuzaki H. Phosphorylation sites of protein kinase C delta in H2O2-treated cells and its activation by tyrosine kinase in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:6587–6592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111158798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Qatanani M., Lazar M.A. Mechanisms of obesity-associated insulin resistance: many choices on the menu. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1443–1455. doi: 10.1101/gad.1550907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ostman A., Frijhoff J., Sandin A., Bohmer F.D. Regulation of protein tyrosine phosphatases by reversible oxidation. J. Biochem. 2011;150:345–356. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lavrovsky Y., Chatterjee B., Clark R.A., Roy A.K. Role of redox-regulated transcription factors in inflammation, aging and age-related diseases. Exp. Gerontol. 2000;35:521–532. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Speciale A., Chirafisi J., Saija A., Cimino F. Nutritional antioxidants and adaptive cell responses: an update. Curr. Mol. Med. 2011;11:770–789. doi: 10.2174/156652411798062395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tornatore L., Thotakura A.K., Bennett J., Moretti M., Franzoso G. The nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathway: integrating metabolism with inflammation. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kamata H., Manabe T., Oka S., Kamata K., Hirata H. Hydrogen peroxide activates IkappaB kinases through phosphorylation of serine residues in the activation loops. FEBS Lett. 2002;519:231–237. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jamaluddin M., Wang S., Boldogh I., Tian B., Brasier A.R. TNF-alpha-induced NF-kappaB/RelA Ser(276) phosphorylation and enhanceosome formation is mediated by an ROS-dependent PKAc pathway. Cell. Signal. 2007;19:1419–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Matthews J.R., Kaszubska W., Turcatti G., Wells T.N., Hay R.T. Role of cysteine62 in DNA recognition by the P50 subunit of NF-kappa B. Nucl. Acids Res. 1993;21:1727–1734. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.8.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pineda-Molina E., Klatt P., Vazquez J., Marina A., Garcia de Lacoba M. Glutathionylation of the p50 subunit of NF-kappaB: a mechanism for redox-induced inhibition of DNA binding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14134–14142. doi: 10.1021/bi011459o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Motohashi H., Yamamoto M. Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism. Trends Mol. Med. 2004;10:549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Baird L., Dinkova-Kostova A.T. The cytoprotective role of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Arch. Toxicol. 2011;85:241–272. doi: 10.1007/s00204-011-0674-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]