Abstract

Patient: Female, 15

Final Diagnosis: Varicella Zoster aseptic meningitis

Symptoms: —

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Lumber punctur

Specialty: Infectious Diseases

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Neurologic complications can occur with varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection, usually after vesicular exanthem. A review of the literature revealed 3 cases of viral meningitis associated with 6th nerve palsy but without significantly increased intracranial pressure.

Case Report:

We report a case of a previously healthy 15-year-old girl with aseptic meningitis as a result of reactivated-VZV infection with symptoms of increased intracranial pressure and reversible 6th cranial nerve palsy but without exanthema.

Diagnosis was made by detection of VZV-DNA in cerebrospinal fluid using polymerase chain reaction and documented high intracranial pressure. Full recovery was achieved after a course of acyclovir and acetazolamide.

Conclusions:

This case demonstrates that VZV may be considered in cases of aseptic meningitis in immunocompetent individuals, even without exanthema, and it may increase the intracranial pressure, leading to symptoms, and causing reversible neurological deficit.

MeSH Keywords: Abducens Nerve Diseases; Herpesvirus 3, Human; Intracranial Hypertension; Meningitis, Aseptic

Background

Varicella-Zoster virus (VZV) remains dormant in the cranial and dorsal root ganglia, with the potential for reactivation as shingles (zoster) [1]. Neurologic complications are known to occur with VZV infection, especially in the immunocompromised, and usually in association with a vesicular rash [2,3]. A series of cases has been reported in the literature of reactivation of VZV in immunocompetent patients and direct invasion of cranial nerves, with partial or complete recovery [4–10], but none with significant increase in the intracranial pressure.

We report a case of a previously healthy immunocompetent 15-year-old girl with acute aseptic meningitis without exanthema, as a result of reactivated VZV infection and significant increase in intracranial pressure.

Case Report

A 15-year-old girl complained of 1-week history of severe headache, new-onset diplopia, blurring of vision, nausea, and vomiting for 3 days. The headache was severe, persistent, with no special character, and with no exacerbating or relieving factors. The headache severity gradually increased over a 1-week period, with no improvement following analgesia. The blurring of vision and diplopia were mostly on her leftward gaze. She denied any history of fever, photophobia, neck stiffness, skin rash, or recent travel. However, an episode of varicella infection in her childhood was reported by her parents, with no history of Zoster. Apart from that, her medical history was unremarkable. She was not taking any medications or oral contraceptive pills. Her family history is not significant.

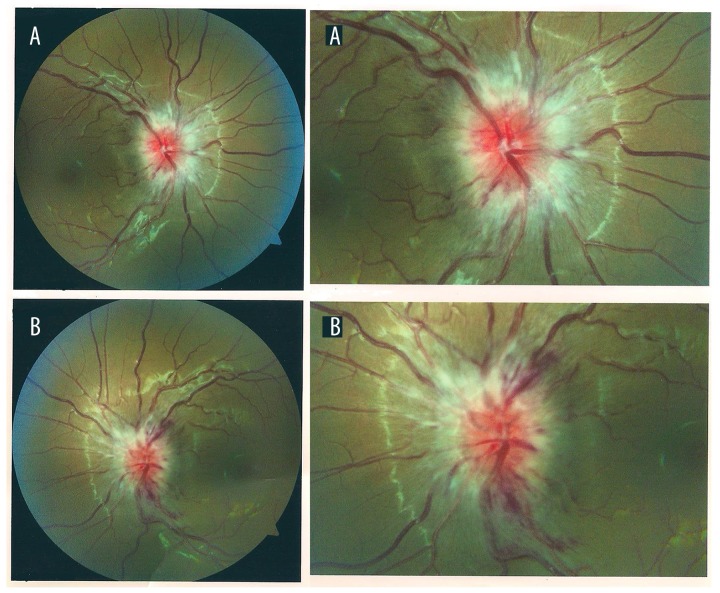

On examination, the patient was alert, oriented, and overweight, with a BMI of 28 kg/m2. Her vital signs were normal. No fever or skin rash was reported. Her examination revealed no signs of meningeal irritation, and she had normal papillary reflexes and bilateral papilledema (Figure 1). Cranial nerves examinations were normal except for left abducent nerve palsy and diplopia in both right and left gaze. The rest of her full neurological assessment was within normal limits. Her blood tests revealed normal renal, liver, and bone biochemistry. Normal inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and Erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and white cell count of 5.3×103 per mm3 were 41% neutrophils, 45% lymphocytes, 11.4% monocytes, 1.3% eosinophils, and 0.4% basophils.

Figure 1.

Fundus photograph (A) Right eye, (B) left eye. Shows bilateral papilledema.

Imaging studies including chest x-ray, computed tomography (CT), MRI, and MRA of the brain failed to show any evidence of cerebral venous thrombosis, vasculitis, or other abnormalities.

Lumber puncture revealed an opening pressure was 53 cm of water (normal opening pressure 10–20 cm of H2O), 537 white blood cells, with the following differential (lymphocytes 96%, monocytes 3% and segmented 1%), 17 red cells/mm3, protein of 62mg/dL (normal protein 15–45 mg/dL), and glucose of 2.3 mmol/L (blood glucose of 6mmol/L). Gram stain, Indian ink for Cryptococcal neoformans capsule and CSF cultures were negative

CSF cytology did not demonstrate any malignant cells, and CSF polymerase chain reactions (PCR) for herpes simplex virus I and II, enterovirus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, adenovirus mumps, Parecho virus, and TB were negative. A positive VZV DNA PCR was detected in the CSF sample, but plasma serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was nonreactive.

The patient was treated with IV Acyclovir for 14 days together with Acetazolamide 250 mg PO BID. Her symptoms resolved gradually with complete recovery of her diplopia and headache. She was discharged home following a normal parametric visual study and instructed to have a regular ophthalmology follow-up for her papilledema.

Discussion

Reactivated VZV can cause wide varieties of neurologic disease [2,3]. The discovery of PCR increases the detection rate in diagnosis of viral meningitis due to herpes simplex type 2 (HSV-2) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) [11].

Several studies conducted in patients with herpes zoster have demonstrated that subclinical meningeal irritation can occur in 40–50% of cases [12,13], but a careful review of the literature showed that VZV-related neurologic disease can occur without the classic herpes zoster exanthema, even in immunocompetent patients. There are several reported cases about VZV reactivation; Klein et al. reported on a 14-year-old a patient with the same clinical presentation but lacking symptoms and signs of increased intracranial pressure [14].

Moreover, 6 cases of VZV meningitis confirmed by PCR have been reported, and those cases failed to show any skin manifestation [15]. This may confirm the ability of the latent virus in the spinal ganglia to travel directly to the central nervous system without the classical skin involvement.

The present case demonstrates the same phenomenon, but with increased intracranial pressure as a predominant clinical feature. The mechanism behind this increase remains poorly understood. However, this can be explained by one of the postulated theories, where superimposed infection of baseline subclinical pseudotumor cerebri or caused primarily by the VZV meningitis. Further explanation suggested by Lo et al. is the post-infectious allergic response to the causative virus and diffuse brain swelling [16]. In their series of 3 cases of aseptic meningitis with similar complications, the causative virus was not identified in 2 cases, while in the third case evidence of herpes infection was detected. In the present case, the viral etiology was proven. Similar to our case, complications appeared at between 11 and 16 days from the start of the illness. Table 1 summarizes the previous case reports of aseptic meningitis with neurological complications and compares it with the present case presentation.

Table 1.

Summarizes the previous case reports of aseptic meningitis with neurological complications and compares it with present case presentation.

| References | Ag (Yr.) | Sex | Presenting symptoms | Meningeal signs | Nerve palsy | Lymphocytes/mm3 | CSF finding glucose mmol | Protein/dl | Culture | Causative agent | Opening pressure in cm water | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our case | 15 | Female | Headache Nausea, Vomiting | No | LT 6th nerve | 515 | Normal | 0.62 | Negative | VZV* by PCR | 53 | Acyclovir + acetazolamide | Complete recovery after 2 week |

| Slo et al. 1991 (Case 1) | 14 | Female | Fever Headache Diarrhea | Yes | RT 6th nerve | 104 | Normal | 0.64 | Negative | Presumed Enterovirous ** | 30 | Conservatively | Complete recovery after 2 week |

| Slo et al. 1991 (Case 2) | 28 | Female | Fever Headache vomiting Diarrhea | Yes | RT 6th nerve | 12 | Normal | 0.67 | Negative | Presumed Enterovirous ** | 14.8 | Conservatively | Complete recovery after 3 week |

| Slo et al. 1991 (Case 3) | 22 | Male | Headache & Sore throat | No | LT 6th nerve | Normal | Normal | 0.32 | Negative | CSF serology herpes simplex IgM | 18 | Conservatively | Complete recovery after 24 week |

VZV – Varicella Zoster Virus,

Based on clinical Judgment.

The high opening pressure in our patient (53 cm of water) compared to previous reported cases may favor the first theory – subclinical pseudotumor cerebri with superadded infection. However, the dramatic response to antiviral medication suggests that aseptic meningitis was the direct cause of her symptoms. Moreover, a recently published review concluded that reactivation of herpes simplex virus isoform 1 (HSV-1) and/or herpes zoster virus (HZV) from the geniculate ganglia is the most strongly suspected cause of isolated Bell’s palsy [17].

Another theory describes Bell’s palsy as an acute demyelinating disease, which may have a pathogenic mechanism similar to that of Guillain-Barré syndrome [18,19]. It has been suggested that they both represent an inflammatory demyelinating neuritis in which Bell’s palsy can be considered a mono-neuritic variant of Guillain-Barré [19,20]. This may partially explain the involvement of the abducent never in this case, but fails to clarify the increased cranial pressure.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates that VZV may be considered in cases of aseptic meningitis in immune-competent individuals, even without exanthema, and it may increase the intracranial pressure, leading to symptoms and causing reversible neurological deficit.

References:

- 1.Eshleman E, Shahzad A, Cohrs RJ. Varicella zoster virus latency. Future Virol. 2011;6(3):341–55. doi: 10.2217/fvl.10.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilden DG, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, et al. Neurologic complications of the reactivation of varicella zoster virus. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:635–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gnann JW. Varicella-zoster virus, atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;86:S91–98. doi: 10.1086/342963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mantero V, De Toni Franceschini L, Lillia N, et al. Varicella-zoster meningoencephaloradiculoneuropathy in an immunocompetent young woman. J Clin Virol. 2013;57(4):361–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gómez-Torres A, Medinilla Vallejo A, Abrante Jiménez A, Esteban Ortega F. Ramsay-Hunt syndrome presenting laryngeal paralysis. Acta Otorrinolaringológica Española. 2013;64(1):72–74. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haargaard B, Lund-Andersen H, Milea D. Central nervous system involvement after herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(7):806–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karmon Y, Gadoth N. Delayed oculomotor nerve palsy after bilateral cervical zoster in an immunocompetent patient. Neurology. 2005;65(1):170. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000167287.02490.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu S, Walker M, Czartoski T, et al. Acyclovir responsive brain stem disease after the Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2004;217(1):111–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terborg C, Förster G, Sliwka U. Unusual manifestation of zoster sine herpete as unilateral caudal cranial nerve syndrome. Der Nervenarzt. 2001;72(12):955–57. doi: 10.1007/s001150170010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maigues Llácer JM, Pujol Farriols R, Pérez Sáenz JL, Fernández Viladrich P. Meningitis caused by varicella-zoster virus and ophthalmic trigeminal neuralgia without skin lesions in an immunocompetent woman. Med Clin (Barc) 1998;111(6):238–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franzen-Röhl E, Tiveljung-Lindell A, Grillner L, Aurelius E. Increased detection rate in diagnosis of herpes simplex virus type 2 meningitis by real-time PCR using cerebrospinal fluid samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(8):2516–20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00141-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robillard RB, Hilsinger RL, Jr, Adour KK. Ramsay Hunt facial paralysis: clinical analyses of 185 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;95(3 Pt 1):292–97. doi: 10.1177/01945998860953P105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee DH, Chae SY, Park YS, Yeo SW. Prognostic value of electroneurography in Bell’s palsy and Ramsay-Hunt’s syndrome. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006;31(2):144–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2006.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein NC, McDermott B, Cunha BA. Varicella-zoster virus meningoencephalitis in an immunocompetent patient without a rash. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42(8):631–33. doi: 10.3109/00365540903510716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Echevarría JM, Casas I, Tenorio A, et al. Detection of varicella-zoster virus-specific DNA sequences in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with acute aseptic meningitis and no cutaneous lesions. J Med Virol. 1994;43(4):331–35. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890430403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo S, Phillips DI, Peters JR, et al. Papilloedema and cranial nerve palsies complicating apparent benign aseptic meningitis. J R Soc Med. 1991;84(4):201–2. doi: 10.1177/014107689108400406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zandian A, Osiro S, Hudson R, et al. The neurologist’s dilemma: a comprehensive clinical review of Bell’s palsy, with emphasis on current management trends. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:83–90. doi: 10.12659/MSM.889876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aviel A, Ostfeld E, Burstein R, et al. Peripheral blood T and B lymphocyte subpopulations in Bell’s palsy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1983;92:187–91. doi: 10.1177/000348948309200218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greco A, Gallo A, Fusconi M, et al. Bell’s palsy and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:323–28. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaco J. Subclinical peripheral nerve involvement in unilateral Bell’s palsy. Am J Phys Med. 1973;52:195–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]