Abstract

Purpose of review

To describe progress and challenges to elimination of mother-to-child HIV transmission (EMCT) in high-income countries.

Recent findings

Despite ongoing declines in the number of perinatally HIV-infected infants in most high-income countries, the number of HIV-infected women delivering may be increasing, accompanied by apparent changes in this population, including higher percentages with antiretroviral “pre-treatment” (with possible antiretroviral resistance), other co-infections, mental health diagnoses, and recent immigration. The impact of antiretroviral resistance on mother-to-child transmission is yet to be defined. A substantial minority of infant HIV acquisitions occur in the context of maternal acute HIV infection during pregnancy. Some infant infections occur after pregnancy, e.g., by premastication of food, or breastfeeding (perhaps by an uninfected woman who acquires HIV while breastfeeding).

Summary

The issues of EMCT are largely those of providing proper care for HIV-infected women. Use of combination antiretroviral therapy by increasing proportions of the infected population may function as a structural intervention important to achieving this goal. Providers and public health systems need to be alert for HIV-serodiscordant couples in which the woman is uninfected and for changes in the population of HIV-infected pregnant women. Accurate data about HIV-exposed pregnancies is vital to monitor progress toward EMCT.

Keywords: Human immunodeficiency virus, mother to child transmission, perinatal, elimination, prevention

Elimination of mother-to-child HIV transmission (EMCT) has been adopted as a goal in high-income countries such as the United States (US) [1] and the countries of Europe [2], and also in less-resourced countries [3]with much higher incidences of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV. In the US, the achievements of the past two decades leading to this goal are the result of the following:1) early and ongoing clinical research, 2) proactive public health policies and recommendations, 3) dedicated funding for clinical care (including laboratory monitoring, antiretrovirals [ARV] for prophylaxis and treatment, and alterations in obstetric practice), 4) case management services through Medicaid and the federal Ryan White Program and, 5) federal and state public health support for surveillance for MTCT, HIV testing, and public education. Ongoing cases of MTCT continue, however, and will challenge clinicians and public health professionals to adapt as the population of HIV-infected pregnant women changes. If at one time the emphasis was on young women with untreated HIV infection diagnosed during pregnancy, the contemporary population also includes substantial numbers of older women who may have knowledge of their HIV status, experience with ARV's, viral strains resistant to antiretroviral therapy (ART), viral co-infections, or recently immigrated. After an epidemic of more than 30 years, after nearly 20 years of effective prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) and treatment of HIV, this paper describes changes in the population of pregnant HIV-infected women (Table 1) in the US and other high-income countries, as well as challenges (Table 2) for the health-care and public health systems which will affect EMCT in the years to come.

Table 1. Perinatal HIV infections in resource-rich countries: numbers, maternal and infant characteristics, and preventive interventions.

| Characteristics and countries | Study period | Estimates |

|---|---|---|

| Numbers of Cases | ||

| Perinatal Infections | ||

| MCT Rates | ||

| USA [21, 22] | 2000-2003 | 3.7% |

| 2005-2008 | 2.2% | |

| Spain [7] | 2000-2003 | 1.4% |

| 2004-2007 | 1.8% | |

| Numbers per year | ||

| USA [4, 8] | 2009 | 151 |

| 2010 | 164 | |

| Europe [9] | 2004 | 347 |

| 2011 | 494 | |

| Incidence per million | ||

| UK [5] | - | 10 |

| France [6] | 2003-2006 | 9 |

| HIV-infected women delivering | ||

| USA [14] | 2006 | 8700 |

| USA (number/1000 person years) [18] | 1994-1995 | 57/1000 PY |

| 2001-2002 | 142/1000 PY | |

| UK/Ireland [5, 13] | 2006-2010 | >1300/yr |

| 2000-2001 | 3.4% | |

| 2008-2009 | 4.5% | |

| Foreign birth (%) among: | ||

| Infected children | ||

| USA [10] | 2007-2010 | 33% |

| France [6] | 2006 | 69% |

| UK [11] | 2011 | 73% |

| HIV-infected mothers of infected children | ||

| USA [26] | 2003-2007 | 21% |

| HIV-infected women delivering | ||

| Canada [25] | 2007-2009 | 60% |

| UK/Ireland [12, 15] | 1990-1993 | 43.5% |

| 2004-2006 | 78.6% | |

| 2000-2009 | 78.5% | |

| France [27] | 1984-1986 | 12% |

| 2003-2004 | 64% | |

| Italy [28] | 2002 | 23.9% |

| 2008 | 45.2% | |

| Spain [7] | 2000-2003 | 11.4% |

| 2004-2007 | 22.1% | |

| Characteristics of HIV-Infected women | ||

| Repeat Pregnancies | ||

| UK/Ireland [15] | 1997 | 20.3% |

| 2009 | 38.6% | |

| Europe [16] | 1989 | 2% |

| 2003-2004 | 14% | |

| France [17] | 2009 | 30% |

| Use of cART/HAART at time of conception | ||

| UK [41] | 2000-2006 | 24% |

| Adherence during pregnancy and postpartum [43] | ||

| USA (pregnancy) | 2001-2005 | 61% |

| USA (post-partum) | 2001-2005 | 44% |

| Injection Drug Use | ||

| USA [21, 22] | 2000-2003 | 11% |

| 2005-2008 | 8% | |

| Illicit drug use | ||

| USA [21, 22] | 2000-2003 | 20% |

| 2005-2008 | 11% | |

| Hard drug use | ||

| USA [23] | 2007-2010 | 3% |

| Positive mental health screen & drug use | ||

| USA [24] | 2007-2010 | 35% |

| Acute HIV infection during pregnancy or breastfeeding | ||

| USA [48] | 2005-2010 | 8% |

| USA (NYS) [50] | 2002-2005 | 14% |

| UK [49] | 2002-2005 | 11.5% |

| Co-infection w/hepatitis B | ||

| Puerto Rico [59] | 1989-1990 | 12.5% |

| USA (Dallas) [60] | 1993-2003 | 1.5% |

| Europe [61] | 1999-2005 | 4.9% |

| Netherlands [62] | 1997-2008 | 4.9% |

| Italy [28] | 2000-2008 | 4% |

| UK (London) [47] | 2000-2009 | 4% |

| USA (hepatitis B or C) [63] | 2006-2010 | 29% |

| Co-infection w/hepatitis C | ||

| Puerto Rico [59] | 1989-1990 | 12.5% |

| USA [64] | 1989-1995 | 29% |

| Italy [28] | 2002 | 29.2% |

| USA (Dallas) [60] | 1993-2003 | 4.9% |

| Europe [61] | 1999-2005 | 12.3% |

| Netherlands [62] | 1997-2008 | 2.1% |

| Italy [28] | 2008 | 17.3% |

| UK (London) [47] | 2000-2009 | 1.6% |

| USA (hepatitis B or C) [63] | 2006-2010 | 29% |

| Negative male partner | ||

| USA (n=181) [31] | - | 62% |

| France (n=555) [32] | - | 43.6% |

| Desire/Intention to have children | ||

| USA (n=181) [31] | ||

| Desire | - | 59% |

| Intend | - | 66% |

| USA (n=50) [35] | ||

| Intend | 2003-2004 | 70% |

| Canada (n=490) [34] | ||

| Desire | 2007-2009 | 69% |

| Intend | 2007-2009 | 56% |

| UK (n=450) [33] | ||

| Desire | 2003-2004 | 75% |

| France (n=555) [32] | ||

| Expect | - | 33% |

| Perinatal Prevention Cascade | ||

| Discussed contraception with provider | ||

| USA [39] | 2008-2010 | 50.6% |

| Unplanned pregnancy after diagnosis | ||

| USA [40] | 2007-2009 | 88% |

| Diagnosed before pregnancy | ||

| USA [21, 22] | 2000-2003 | 60% |

| 2005-2008 | 68% | |

| Established HIV dx during pregnancy | ||

| Italy [28] | 2008 | 32.9% |

| Use of cART in pregnancy | ||

| USA [23] | 2007-2011 | 85% |

| Spain [7] | 2004-2007 | 99.4% |

| Italy [28] | 2007-2008 | 95.5% |

| UK/Ireland [41] | 2000-2006 | 82.1% |

| Maternal viral suppression (undetectable) | ||

| USA (VL >1000c/ml) [23] | - | 15% |

| Europe [46] | 2000-2010 | 65% |

| Europe (ARV naïve) [65] | 1997-2004 | 73% |

| France [17] | 2005-2008 | 65% |

| Italy [28] | 2000 | 37.3% |

| 2008 | 80.9% | |

| London [47] | 2000-2009 | 77% |

| Pregnant women with VL<50 | ||

| After 3 months of tx [66] | - | 61.5% |

| After 6 months of tx | - | 67.9% |

| Mode of delivery: Cesarean | ||

| USA [21, 22] | 2000-2003 | 36% |

| 2005-2008 | 40% | |

| Europe [46] | 2000-2010 | 58% |

| Italy [28] | 2008 | 63.2% |

| UK/Ireland [12] | 1997 | 38.3% |

| 1999 | 66.4% | |

| 2006 | 50% | |

| Spain [7] | 2000-2003 | 57.6% |

| 2004-2007 | 46.5% | |

Table 2. Challenges and Opportunities.

| Antiretrovirals: |

| “Pre-treatment” |

| Resistant HIV |

| Prenatal exposure increasing |

| HIV-infected pregnant women: |

| Age |

| Numbers of pregnanciesincreasing |

| Acute HIV infection |

| Substance abuse |

| Mental health |

| Viral co-infections |

| Morbidity, additionaldrug exposure |

| Immigration |

| Poverty/housing instability |

| HIV-discordant couples with seronegative women |

| Contraception and family planning services, consistent access |

| Health-care system: |

| Affordable Care Act |

| Ryan White Care Program |

| Local systems failures in consistently providing the full cascade of interventions |

| Public Health system: |

| Financial support for programs |

| Data |

| Testing laws, state |

Numbers of cases

HIV-infected infants

The United States and nearly all western European countries reportvery low annual numbers of perinatally infected infants and children [4-8]. The numbers of infected children in the World Health Organization's European region, however, increased from 347 to 494 between 2004 and 2011, largely because of the number of infections inits eastern and central sub-regions [9].

Among HIV-infected children in the US and Europe, birth in lesser-resourced countries, most often sub-Saharan Africa, is becoming more frequent. During 2007-2010, foreign-birth was reported for 33% (295/884) of HIV-infected children diagnosed with HIV in the US [10], and an even greater proportion of foreign birth was reported for infected children in France and in the United Kingdom (UK), at 60% and 73%, respectively [6, 11].

HIV-infected pregnant women

In several resource-rich countries, an increase in the number of HIV-infected pregnant women delivering annually has been reported in the last decade [5, 12-14]. Repeat pregnancies among HIV-infected women are increasing in European countries [15-17]. The live-birth rate of HIV-infected women in the US increased 150% from the era before highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) (pre-HAART era, 1994-1995) to the HAART era (2001-2002) [18], while, on the other hand, pregnancy rates between 1994 and 2009 in HIV-infected women were approximately half those in HIV-uninfected women in the US [19, 20].

Characteristics of the population of HIV-infected pregnant women

Injection drug use among HIV-infected pregnant women appears to be declining, from 11% during 2000-2003 to 8% during 2005-2008 in U.S. Enhanced Perinatal Surveillance (EPS); use of any illicit drugs declined from 20% to 11% in the same periods [21, 22]. Another US study, the Surveillance Monitoring of ART Toxicities (SMARTT) cohort reported ‘hard drug use’ by 3% of women in 2007-2010 [23], while also reporting positive behavioral screens for mental disorder (mainly post-traumatic stress disorder) or substance abuse in 35% compared to 26% in the general population [24].

Immigrants from lesser-resourced countries account for an increasing proportion of HIV-exposed deliveries, including 78.5% of infected women delivering in the UK during 2000-2009 [15] and 60% in Canada during 2007-2009 [25]. Among mothers of HIV-infected infants reported to US National HIV Surveillance during 2003-2007, 21% were born in countries other than the US [26]. The annual percentage of HIV-infected pregnant women born in Africa and delivering was 24-78% in several western European countries during the past decade [7, 12, 27, 28]. Immigrant women were at some risk of less frequent uptake of PMTCT interventions, specifically, accessing prenatal care and ARV initiation [27, 29].

An estimated 140,000 HIV-serodiscordant heterosexual couples reside in the US [30], but whether that number or its proportion of HIV-infected persons is changing is unknown. It is known that many HIV-infected women have HIV-uninfected partners. Of 181 HIV-infected US women of childbearing age, 62% had negative partners and 11% had partners of unknown status [31]. In France, among HIV-infected individuals, 41.5% of men and 43.6% of women had partners of unknown or negative status [32]. The patterns of serodiscordance offer different opportunities for prevention of HIV MCT, which become more relevant as the population's desire to conceive and bear children increases. One US study of 181 women of childbearing age reported that 59% desired children, of whom 66% intend to have children [31]. Studies from Canada and the UK have reported similar findings [33, 34]. Of HIV-infected persons in France, 20% of men and 33% of women expected to have children [32]. Finally, a study of perinatally infected females of childbearing age found that 70% intended to have children [35]. Safer conception for HIV-discordant couples is being made possible through the use of assisted reproductive technology [30, 36]—e.g., artificial insemination of an HIV positive woman, or so-called ‘sperm washing’, with intrauterine insemination or in vitro fertilization—and antiretrovirals for pre-exposure prophylaxis [37] or treatment as prevention [38]. It remains to be seen whether these approaches will lead to an increase in the annual number of HIV-exposed infants.

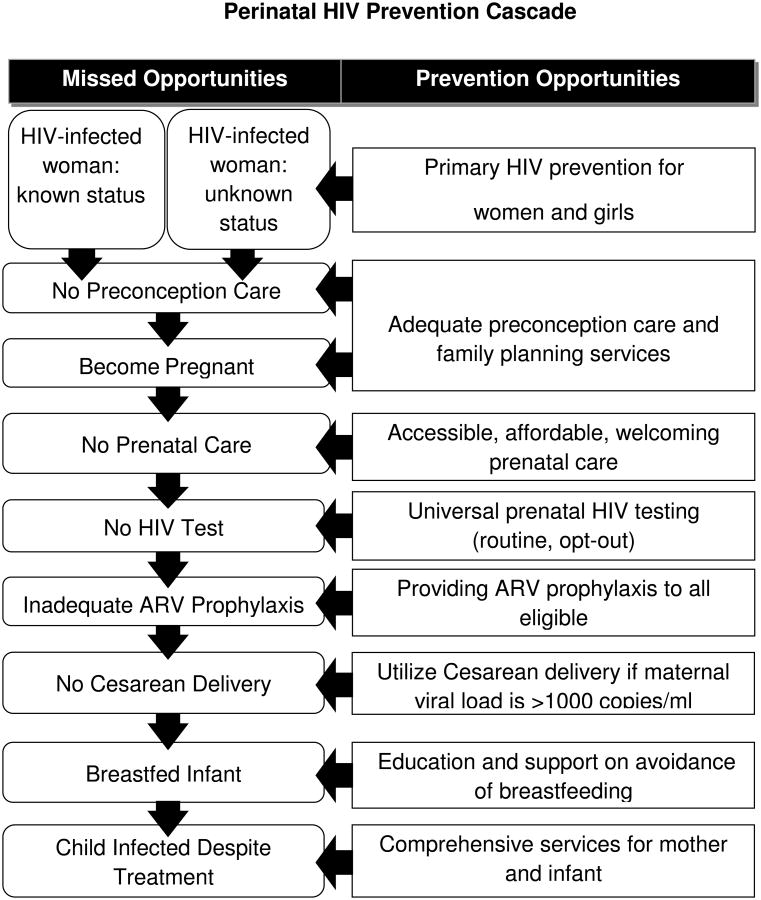

Perinatal Prevention Cascade—uptake of elements

In the US, MTCT has been organized around the perinatal HIV prevention cascade (see Figure), which begins with primary prevention of HIV infection and preconception care of women known to be infected prior to pregnancy a percentage which appears to be increasing [21, 22]. While more women may thus have opportunity to maximize their HIV care and plans for pregnancy, there is a paucity of data about how many HIV-infected women acquire such preconception care. One US study (2008-2010) reported that 50.6% of sexually active HIV-infected women had spoken with a provider within the past year about contraception plans [39]. At least one unplanned pregnancy after learning her HIV diagnosis was reported by 88% in a study of US women [40]. Maternal diagnosis was established before pregnancy in 60% and 68% of cases during 2000-2003 and 2005-2008, respectively [21, 22]. In Italy, 32.9% of HIV-infected pregnant women's diagnoses were made during pregnancy in 2008, a figure unchanged over the preceding decade [28]. In the US, once a diagnosis is made prenatal care was received by a large percentage (88% in 2000-2003and 90% in 2005-2008) [21, 22]. In those periods, use of prenatal, natal (labor and delivery) and post-natal ARV use increased [21, 22]. In SMARTT during 2007-2011, effective combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) use was reported by 85% of women in the ‘dynamic’ cohort [23]. Similar high rates of cART use have been seen in several European countries [7, 28, 41], where its use is frequently reported at the time of conception [16, 41]. Though ARV resistance has been recognized in maternal and infant viral strains, it is not clear that the proportion of affected individuals has changed, nor is the effect on MCT clear [42]. Adherence to ARV's during pregnancy often exceeds that in the post-partum period [43, 44]. Uptake of PMTCT interventions and viral load suppression–but not MCT rate—are highly associated with a woman's disclosure of her diagnosis to her partner [45].

Figure. Perinatal HIV Prevention Cascade.

Maternal viral suppression appears to be increasingly common in recent years. In SMARTT, only 15% in the ‘dynamic’ cohort had VL > 1000 copies/ml [23]. In several European cohorts, viral RNA was frequently undetectable at the time of delivery: 65% in the European Collaborative Study [46]; 65% in the French Perinatal Cohort [17]; 80.9% in Italy [28]; and 77% in London [47].

Mode of delivery of infants to HIV-infected women in the US was by elective Cesarean-section in 36% during 2000-2003 [21] and 40% during 2005-2008 [22]. While the Cesarean-section rate has been higher in Europe [28, 46], the rates have declined in UK/Ireland, from a peak of 66.4% in 1999to 50% in 2006 [12]. Similarly, in Spain the elective Cesarean delivery rate was 57.6% in 2000-3 and 46.5% in 2004-7 [7].

“Other” opportunities for HIV MCT

There are several opportunities for MTCT which don't fit neatly into, or whose issues transcend, the list of prevention interventions—and their converse, missed opportunities— in the perinatal prevention cascade. Women with acute HIV-infection—that is, women who seroconvert to HIV-positive status—during pregnancy or breastfeeding are more likely to transmit HIV to their infants, mainly because of higher HIV VL's which occur, albeit transiently, during acute HIV infections. Such infections are typically the result of partnerships of an HIV-infected man and HIV-uninfected woman. That number is not precisely known, but it is vital that individuals be alerted to the additional risk attendant to such partnerships. The proportion of perinatal HIV transmissions which occur under these conditions in recent years is 8% in the U.S. among cases reported to EPS during 2005-2010 [48], 11.5% in the UK audit of transmissions which occurred during 2002-2005 [49], and 14% in cases reported to New York State during 2002-2006 [50]. As overall MCT rates decline among women with established HIV diagnoses, it is possible that those with acute infection may comprise an increasing proportion of MCT. It has been suggested that the rate of acute infection in adolescent females may behigh because of the high HIV incidence among adolescent males [51], some of whom have sex with both males and females. Among HIV-infected females of reproductive age is an increasing number who acquired infection perinatally [52]. Though these women may deliver prematurely or require Cesarean delivery more frequently, they appear to transmit HIV to their infants at a rate similar to other HIV-infected women [52]. Finally, there are the so-called “late” perinatal transmissions, which may result from infants ingesting “premasticated” food, from being breastfed by an HIV-infected woman, or from behaviors which are difficult to characterize; some of these infants, though born to HIV-infected women, have repeatedly negative nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) before they have a NAAT result which establishes their diagnosis [53].

Challenges for EMCT

The annual number of HIV-infected infants born in the US and most other high-income countries is decreasing. Though the numbers of deliveries by HIV-infected pregnant women appears to be increasing, at least in the US, this trend is not the result of increasing incidence among women, as HIV incidence is actually decreasing [54]. The increased number of deliveries appears to be the result of improved survival and overall well-being, accompanied by increasing desire to conceive and increasing numbers of women with ‘repeat’ pregnancies. Whether the number of HIV-exposed pregnancies will further increase as the availability of assisted reproductive technologies increases—and how such technologies will change PMTCT—remains to be seen. The evident connection between survival and ART means that increasing numbers of women will be ART-experienced when they conceive. It can be anticipated that recent ART guidelines, which recommend treatment for all HIV-infected persons [55], when implemented, will constitute an important structural intervention for EMCT, leading to an increasing proportion with viral suppression among women of childbearing age. This experience leads not only to increased prenatal ARV exposure, but also the possibility of an increasing prevalence of ARV-resistant HIV, which in turn could result in more women being on second- and third-line regimens whose effectiveness may differ So far, MTCT does not appear to be substantially affected by ARV-resistance [42]. Additional antiviral exposure—as well as additional maternal morbidity--in this population may occur as a result of maternal co-infection with other viruses, notably hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses. Though immigrant HIV-infected women of childbearing age comprise an increasing percentage in many resource-rich countries, their PMTCT problems relate more to health care access and utilization (e.g., timely diagnosis, linkage to and retention in primary and prenatal care) than to biomedical issues (e.g., resistant virus, adherence).

In the US, most of the ongoing mother-to-childtransmissions are apparently attributable to incomplete uptake of elements of the Perinatal Prevention Cascade, e.g., identification of HIV-infected women and effective retention of them in care [56]. It is likely that many of such transmissions are from women who are extremely difficult to reach, for reasons in addition to illicit drug abuse, reasons which include the substantial degree of poverty [57] and mental health problems in the population. The expansion in medical care access in the U.S. anticipated from the Affordable Care Act may mitigate some of poverty's effects, but it can be predicted that the social instability and segregation associated with poverty will continue to aggravate problems of access. Indeed, in this era of low MCT rates, as each transmission's specific characteristics take on heightened importance, it remains important to review cases, with the goal of changing the local system in ways that may prevent further transmissions and improve the care of HIV-infected women to optimize their health prior to—and between—pregnancies, as well as to prevent unwanted pregnancies. The Framework for EMCT [1] incorporates Case Review and Community Action as one of its key components, as the Fetal-Infant Mortality Review—HIV (FIMR-HIV) Prevention Program. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention includes FIMR-HIV among activities encouraged by its prevention grantees. These reviews have identified issues of domestic violence and maternal mental health diagnoses [58]. FIMR-HIV has also recognized the dramatic effect on women—including depression and decreased linkage to care and medication adherence—when they lose custody of children after birth.

Conclusion

It will remain a challenge for public health institutions to commit new funds to PMTCT as the numbers of perinatal cases decline in contrast to the number of adult cases and when comparing resource-rich to resource-poor settings. Actionable data on the number of HIV-infected women delivering, and on the kind of care they receive, is essential for public health authorities to monitor EMCT adequately. Support for this can come from state laws and policies which advocate “opt-out” HIV testing and encourage perinatal HIV exposure reporting. Medical care providers must be made aware of changes in these policies. Vital to all of these considerations, however, is the recognition that “elimination” of mother-to-child transmission is not a single event, but, rather, is an ongoing process. That process necessarily must address the needs of successive annual waves of HIV-infected pregnant women as long as there are new cases of HIV in women, underscoring the importance of primary prevention and appropriate HIV care for women.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Nesheim SR, et al. A Framework for Elimination of Perinatal Transmission of HIV in the United States. Pediatrics. 2012 doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostergren M, Malyuta R. Elimination of HIV infection in infants in Europe--challenges and demand for response. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11(1):54–7. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Global plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive: 2011-2015. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor A, et al. Estimated Perinatal Antiretroviral Exposures, Cases Prevented and Infected Infants in the Era of Antiretroviral Prophylaxis in the US; 2012; CROI; Seattle, WA: Poster 1000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. British Paediatric Surveillance Unit Annual Report 2011/12. 2012 Sep; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heraud-Bousquet V, et al. A three-source capture-recapture estimate of the number of new HIV diagnoses in children in France from 2003-2006 with multiple imputation of a variable of heterogeneous catchability. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:251. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prieto LM, et al. Low rates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 and risk factors for infection in Spain: 2000-2007. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(10):1053–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31826fe968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2010. HIV Surveillance Report. 2012;22 [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe. HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2011. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prosser AT, Tang T, Hall HI. HIV in persons born outside the United States, 2007-2010. JAMA. 2012;308(6):601–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Protection Agency. United Kingdom; New HIV Diagnoses data to end June 2012. Tables No 1:2012. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Townsend CL, et al. Trends in management and outcome of pregnancies in HIV-infected women in the UK and Ireland, 1990-2006. BJOG. 2008;115(9):1078–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huntington SE, et al. Predictors of pregnancy and changes in pregnancy incidence among HIV-positive women accessing HIV clinical care. AIDS. 2013;27(1):95–103. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283565df1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitmore SK, et al. Estimated number of infants born to HIV-infected women in the United States and five dependent areas, 2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(3):218–22. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182167dec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.French CE, et al. Incidence, patterns, and predictors of repeat pregnancies among HIV-infected women in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 1990-2009. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(3):287–93. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823dbeac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Collaborative Study. Increasing likelihood of further live births in HIV-infected women in recent years. BJOG. 2005;112:881–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briand N, et al. Previous antiretroviral therapy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV does not hamper the initial response to PI-based multitherapy during subsequent pregnancy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(2):126–35. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318219a3fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma A, et al. Live birth patterns among human immunodeficiency virus-infected women before and after the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(6):541 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massad LS, et al. Pregnancy rates and predictors of conception, miscarriage and abortion in US women with HIV. AIDS. 2004;18(2):281–6. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401230-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linas BS, et al. Relative time to pregnancy among HIV-infected and uninfected women in the Women's Interagency HIV Study, 2002-2009. AIDS. 2011;25(5):707–11. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283445811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CDC. Enhanced Perinatal Surveillance—Participating Areas in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2000-2003. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Supplemental Report. 13(4) [Google Scholar]

- 22.CDC. Enhanced Perinatal Surveillance--15 areas, 2005-2008. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 16(2) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams PL, et al. A trigger-based design for evaluating the safety of in utero antiretroviral exposure in uninfected children of human immunodeficiency virus-infected mothers. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(9):950–61. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malee K, et al. Third International Workshop on HIV and Women. Toronto: Jan 14-15, 2013. Prevalence and persistence of psychiatric and substance abuse disorders among mothers living with HIV. Abstract O_06. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loutfy M, et al. High prevalence of unintended pregnancies in HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective study. HIV Med. 2012;13(2):107–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor AW, et al. Estimated Number and Characteristics Associated with Perinatal HIV Infections, 33 States and 5 Dependent Areas, United States, 2003-2007. International AIDS Society; Mexico City. Poster A-361-0139-03613: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jasseron C, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission: similar access for sub-Sahara African immigrants and for French women? AIDS. 2008;22(12):1503–11. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283065b8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baroncelli S, et al. Antiretroviral treatment in pregnancy: a six-year perspective on recent trends in prescription patterns, viral load suppression, and pregnancy outcomes. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(7):513–20. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tariq S, et al. The association between ethnicity and late presentation to antenatal care among pregnant women living with HIV in the UK and Ireland. AIDS Care. 2012;24(8):978–85. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.668284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lampe MA, et al. Achieving safe conception in HIV-discordant couples: the potential role of oral preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):488 e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finocchario-Kessler S, et al. Understanding high fertility desires and intentions among a sample of urban women living with HIV in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(5):1106–14. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9637-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heard I, et al. Reproductive choice in men and women living with HIV: evidence from a large representative sample of outpatients attending French hospitals (ANRS-EN12-VESPA Study) AIDS. 2007;21 Suppl 1:S77–82. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000255089.44297.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cliffe S, et al. Fertility intentions of HIV-infected women in the United Kingdom. AIDS Care. 2011;23(9):1093–101. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loutfy MR, et al. Fertility desires and intentions of HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e7925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ezeanolue EE, et al. Sexual behaviors and procreational intentions of adolescents and young adults with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus infection: experience of an urban tertiary center. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(6):719–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savasi V, et al. Reproductive assistance in HIV serodiscordant couples. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(2):136–50. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CDC. Interim Guidance for Clinicians Considering the Use of Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in Heterosexually Active Adults. MMWR. 2012;61(31):586–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen MS, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badell ML, et al. Reproductive healthcare needs and desires in a cohort of HIV-positive women. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:107878. doi: 10.1155/2012/107878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutton MY, Frazier EL. Unplanned Pregnancies among Women in Care for HIV Infection --United States, 2007-2009; CROI; 2012; Seattle, WA. Poster 185. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Townsend CL, et al. Low rates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV following effective pregnancy interventions in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 2000-2006. AIDS. 2008;22(8):973–81. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f9b67a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weidle PJ, Nesheim S. HIV drug resistance and mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37(4):825–42, x. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mellins CA, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral treatment among pregnant and postpartum HIV-infected women. AIDS Care. 2008;20(8):958–68. doi: 10.1080/09540120701767208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nachega JB, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy during and after pregnancy in low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2012;26(16):2039–52. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359590f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jasseron C, et al. Non-Disclosure of a Pregnant Woman's HIV Status to Her Partner is Associated with Non-Optimal Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(2):488–97. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0084-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aebi-Popp K, et al. Pregnant women with HIV on ART in Europe: how many achieve the aim of undetectable viral load at term and are able to deliver vaginally? J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(6) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Read PJ, et al. When should HAART be initiated in pregnancy to achieve an undetectable HIV viral load by delivery? AIDS. 2012;26(9):1095–103. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283536a6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh S, et al. HIV Seroconversion During Pregnancy and Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission: Data from Enhanced Perinatal Surveillance, United States, 2005-2010. International AIDS Society; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Study of HIV in Pregnancy and Childhood; Audit, Information Analysis Unit. Perinatal transmission of HIV in England 2002-2005, Executive Summary. 2007 Oct; [Google Scholar]

- 50.Birkhead GS, et al. Acquiring human immunodeficiency virus during pregnancy and mother-to-child transmission in New York: 2002-2006. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(6):1247–55. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e00955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faghih S, Secord E. Increased Adolescent HIV Infection during Pregnancy Leads to Increase in Perinatal Transmission at Urban Referral Center. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2012;11(5):293–5. doi: 10.1177/1545109712446175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Badell ML, Lindsay M. Thirty years later: pregnancies in females perinatally infected with human immunodeficiency virus-1. AIDS Res Treat. 2012;2012:418630. doi: 10.1155/2012/418630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frange P, et al. Late postnatal HIV infection in children born to HIV-1-infected mothers in a high-income country. AIDS. 2010;24(11):1771–6. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.CDC. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(4) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whitmore SK, et al. Correlates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in the United States and Puerto Rico. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e74–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.CDC. Characteristics Associated with HIV Infection Among Heterosexuals in Urban Areas with High AIDS Prevalence --- 24 Cities, United States, 2006--2007. MMWR. 2011;60(31):1045–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schneider E, et al. Fetal and Infant (FIMR)/HIV Prevention Methodology: Identifying gaps in maternal health systems for women living with HIV; National Perinatal Association Annual Conference 2012; Tampa, FL. Poster Session, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deseda CC, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus infection among women attending prenatal clinics in San Juan, Puerto Rico, from 1989-1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(1):75–8. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00319-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santiago-Munoz P, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C in pregnant women who are infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3 Pt 2):1270–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Landes M, et al. Hepatitis B or hepatitis C coinfection in HIV-infected pregnant women in Europe. HIV Med. 2008;9(7):526–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Snijdewind IJ, et al. Hcv coinfection, an important risk factor for hepatotoxicity in pregnant women starting antiretroviral therapy. J Infect. 2012;64(4):409–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buchacz K, et al. Disparities in prevalence of key chronic diseases by gender and race/ethnicity among antiretroviral-treated HIV-infected adults in the US. Antivir Ther. 2013;18(1):65–75. doi: 10.3851/IMP2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hershow RC, et al. Hepatitis C virus coinfection and HIV load, CD4+ cell percentage, and clinical progression to AIDS or death among HIV-infected women: Women and Infants Transmission Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(6):859–67. doi: 10.1086/428121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.European Collaborative, S et al. Time to undetectable viral load after highly active antiretroviral therapy initiation among HIV-infected pregnant women. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(12):1647–56. doi: 10.1086/518284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rachas A, et al. Does pregnancy affect the early response to cART? AIDS. 2013;27(3):357–67. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835ac8bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.