Abstract

The accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) and tau aggregates is a pathological hallmark of Alzheimer's disease. Both polypeptides form fibrillar deposits, but several lines of evidence indicate that Aβ and tau form toxic oligomeric aggregation intermediates. Depleting such structures could thus be a powerful therapeutic strategy. We generated a fragment of tau (His-K18ΔK280) that forms stable, toxic, oligomeric tau aggregates in vitro. We show that (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a green tea polyphenol that was previously found to reduce Aβ aggregation, inhibits the aggregation of tau K18ΔK280 into toxic oligomers at ten- to hundred-fold substoichiometric concentrations, thereby rescuing toxicity in neuronal model cells.

Keywords: Tau protein, tau oligomers, aggregation inhibitors, EGCG, Alzheimer's disease, polyphenol

Introduction

A variety of peptides and proteins are known to assemble into highly ordered aggregate structures with a cross-beta sheet structure, termed amyloid. The brains of patients suffering from Alzheimer's disease (AD) exhibit two types of aggregated protein deposits: extracellular plaques mainly composed of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptide and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of the hyperphosphorylated protein tau, in which the microtubule-binding repeat domain adopts a cross-beta structure1–4. Tau exists in multiple splicing variants and is a highly hydrophilic and thus soluble protein with little propensity to aggregate5. The K18ΔK280 tau protein fragment spans the four repeat domains of the microtubule-binding domain of the longest human isoform tau40; the deletion of lysine 280 has been described in FTDP-176 (Figure 1 A). Filaments of wild-type (wt) tau only form in vitro in the presence of polyanions such as heparin7,8, however K18ΔK280 aggregates into β-sheet rich structures without heparin9.

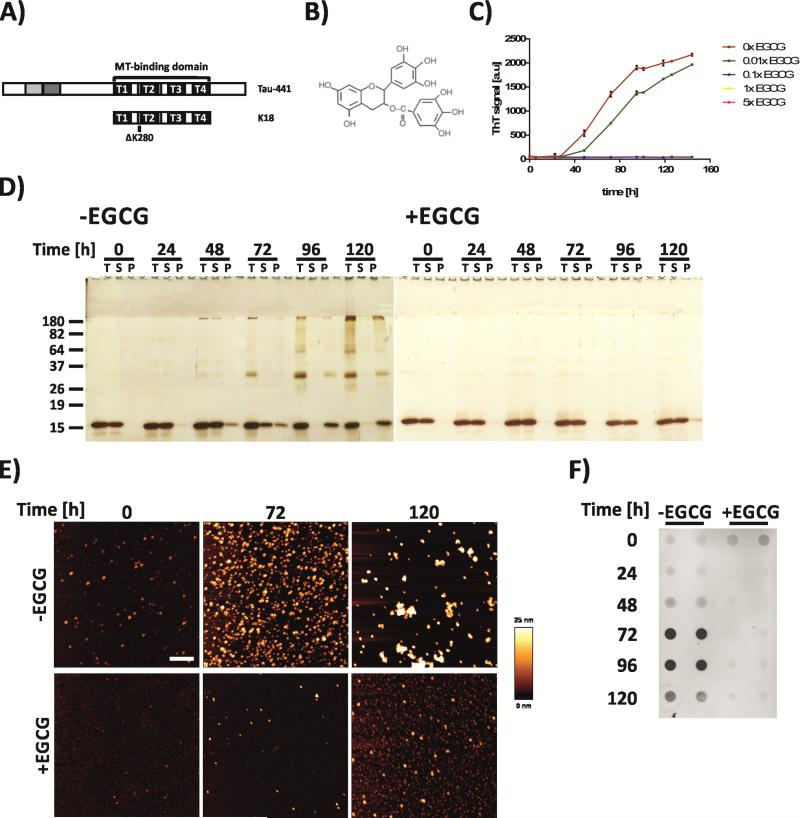

Figure 1. EGCG prevents the formation of tau oligomers and SDS-stable aggregates at substoichmiometric concentrations.

A) Structure of the K18Δ280 tau fragment comprising all four repeat domains (T1-4) of the microtubule-binding domain found in the longest human tau isoform Tau-441and with a deletion of lysine residue 280. B) Structure of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG). C) Effect of ECGC on tau K18ΔK280 aggregation (12.5 μM) as assessed by ThT fluorescence assay. Results represent mean fluorescence signal ± s.d. (n = 3). D) Effects of EGCG (equimolar concentration) on the formation of SDS-stable, high molecular weight tau aggregates. T = total, unfractionated sample, S = supernatant, P = pellet. Fractionation by centrifugal sedimentation at 200,000 × g. E) Analysis of untreated and EGCG-treated (equimolar concentration) K18ΔK280 by atomic force microscopy after 0 h, 48 h and 120 h incubation at 37°C. Scale bar = 500 nm. F) Effects of EGCG on the formation of tau oligomers as assessed by A11 dot blot analysis.

Therapeutic efforts into slowing or reversing the progression of neurodegenerative diseases have concentrated on clearing insoluble protein aggregates or inhibiting the aggregation of amyloidogenic proteins. In recent years, new therapeutic strategies have emerged, which include the stabilization of mature fibrils to deplete toxic oligomers or the redirection of the aggregation cascade to increase the formation of non-toxic, off-pathway aggregates10.

Since two types of fibrillar aggregates are formed from Aβ and tau in AD, small molecules targeting both polypeptides could be a valuable therapeutic strategy. Inhibitors of heparin-induced tau paired helical filament formation were found in the classes of anthraquinones, polyphenols, porphyrins and phenothiazines11,12. The green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) interferes with aggregation of numerous amyloidogenic proteins and small polypeptides and ameliorates their detrimental effects13–18. It stimulates the assembly of non-toxic, unstructured, off-pathway oligomers from Aβ, α-synuclein and IAPP in vitro19,20. Despite challenges in its variable oral bioavailability, short pharmacokinetic half-life, and limited partitioning across the blood-brain barrier, this may make it a promising model drug for AD21,22. However, the effect of EGCG on tau aggregation has not yet been characterized. Here, we developed a cell-free aggregation assay using the tau fragment His-K18ΔK280 to probe the effect of EGCG under physiological conditions in the absence of heparin. We demonstrate that EGCG prevents the formation of β-sheet rich aggregates at substoichiometric concentrations and reduces their toxicity in cell-based assays, suggesting a specific interaction of EGCG with a crucial early aggregation intermediate.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

The construct encoding the tau fragment K18 (K18ΔK280, Figure 1 A), comprising the mutant four-repeat microtubule-binding domain, was kindly provided by M. Holzer. Expression clones for K18ΔK280 with an N-terminal His6-tag were generated using the Gateway® technology (Life Technologies). AttB sites were added to the construct by PCR (forward primer: 5’-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGGatgcagacagcccccgtgcccatgc-3’; reverse primer: 5’-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGTCATTCAATCTTTTTATTTCCTCC-3’). pDONR221 and pDESTco were chosen as entry and expression vectors, respectively. Ni-NTA matrix columns were used for purification of recombinant protein (QIAGEN). Columns were washed with native wash buffer or with wash buffers of decreasing urea concentrations, and the His-tagged protein was eluted under native conditions following the manufacturer's specifications (QIAGEN).

The protein was subjected to reversed-phase purification using Poros 50 R1 resin (Applied Biosciences), washed using 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and eluted with 60% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA, lyophilized and the aliquots stored at −20°C. Protein concentration was determined by OD280 using an extinction coefficient of 8480 M−1cm−1.

Protein aggregation

Lyophilized His-K18ΔK280 protein was reconstituted in PBS and sonicated at 4°C for 5 min. The protein solution was cleared by centrifugation at 200,000 × g and 4°C for 20 min. His-K18ΔK280was incubated at 37°C in 96-well plates at 12.5 μM, with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) added daily to prevent formation of intramolecular disulfide bonds. EGCG (Sigma Aldrich) solutions were freshly prepared with ultrapure H2O.

Thioflavin T assay

To measure aggregation formation, 20 μM Thioflavin T (ThT) was added to each reaction and fluorescence measured in triplicates in black non-binding 96-well plates with clear, flat bottoms (#3651, Corning) using a microplate reader (Infinite M200, Tecan), at excitation and emission wavelengths of 440 and 485 nm, respectively. Results were calculated as means ± s.d.

SDS-PAGE and dot blot assays

Protein samples were either denatured by boiling at 95°C for 10 min with 2% SDS + 50 mM DTT for denaturing SDS-PAGE and denaturing dot blots or diluted with an equal volume of H2O for nondenaturing dot blots. 20 μl were applied to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 h in 3% nonfat milk and incubated overnight with the following primary antibodies at 4°C: polyclonal anti-tau A0024 (aa 243-441, DAKO; 1:2000), anti-amyloid oligomer A11 (1:2000, Life Technologies). Proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence (Chemicon) or the AttoPhos reagent (Promega). NBT staining of nitrocellulose membranes was performed as previously described19,23.

Centrifugal sedimentation

Samples were collected every 24 h and subjected to ultracentrifugation for 20 min at 200,000 × g (70,000 rpm) and 4°C in a TL-100 centrifuge and TLA120.2 rotor (Beckman). Pellets were resuspended in PBS. Unfractionated samples, supernatants and resuspended pellets were boiled in SDS sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining as previously described24.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

20 μl of His-K18ΔK280 samples were pipetted onto freshly cleaved mica fixed onto a glass slide and incubated for 10 min at room temperature, washed 3× with ddH2O, and dried overnight. Samples were analyzed using the Nanowizard AFM (JPK, Berlin) in intermittent contact mode.

Tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy

Protein solutions were diluted 1:10 in PBS. Fluorescence emission was measured at 280 nm absorption wavelength using a fluorescence spectrometer (LS 50, Perkin Elmer).

Cell viability assay

PC-12 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were grown in DMEM F12-K medium supplemented with 14.5% horse serum, 4% fetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 ug/mL streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified environment. Prior to viability assays, DTT was removed from K18ΔK280 aggregate reactions by buffer exchange using a 10 kDa centrifugal filter (Amicon) or by pelleting aggregates by ultracentrifugation (200,000 × g, 20 min), washing and resuspending in PBS. Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay as previously described19. Student's t-test was used to calculate p values.

Results

EGCG substoichiometrically prevents the formation of SDS-stable tau oligomers

First, we assessed the aggregation of tau K18ΔK280 (Figure 1 A) in the absence or presence of EGCG (Figure 1 B) by measuring Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence emission at 485 nm under reducing conditions (Figure 1 C). ThT increases fluorescence on binding to β-sheet rich amyloid-like structures25. In the absence of EGCG, ThT fluorescence increased after an initial lag phase of ca 24 - 30 h. In contrast, incubation of K18ΔK280 with a substoichiometric concentration of EGCG (0.01x tau protein) elongated the lag phase. At higher concentrations of EGCG (0.1×, 1× and 5×), no increase in ThT fluorescence was observed (Figure 1 C), indicating that EGCG blocks the formation of amyloid-like, β-sheet rich tau aggregates. In contrast, EGCG did not prevent the rapid formation of β-sheet rich K18ΔK280 aggregates that were induced by heparin (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2 A), but changed aggregate morphology from large fibrillar assemblies into smaller spherical structures (Supplementary Figure S2 B). Likewise, EGCG reduced ThT binding to heparin-induced full length tau aggregates both under reducing (wt tau) and oxidizing conditions (ΔC tau), but did not delay aggregation or alter the fibrillar morphology of tau aggregates under these conditions (Supplementary Figure S3).

We next analyzed the effects of EGCG on tau aggregation by centrifugal fractionation of samples followed by denaturing SDS-PAGE and silver staining (Figure 1 D). In the absence of EGCG, we found a time-dependent increase of tau in the pellet fractions, indicating the formation of insoluble, high molecular weight aggregates (Figure 1 D). In addition, SDS-stable multimers appeared from 48 hours onwards. In contrast, incubation of the tau fragment with equimolar EGCG eliminated the formation of SDS-stable aggregates (Figure 1 D). Thus, our centrifugation assays confirm that EGCG treatment potently blocks K18ΔK280 aggregation in vitro.

To visualize K18ΔK280 aggregate species, we performed atomic force microscopy (AFM) on samples incubated with or without equimolar concentrations of EGCG. In the absence of EGCG, we observed the time-dependent formation of non-fibrillar, oligomeric K18ΔK280 aggregate species (Figure 1 E). In contrast, only a few small tau aggregate species were observed after incubation with EGCG.

Finally, we performed dot blot assays with the anti-oligomer antibody A11 in order to examine whether the spontaneously formed K18ΔK280 aggregates are toxic, disease relevant structures. Previous studies have demonstrated that A11 detects proteotoxic, oligomeric aggregate species of Aβ, tau and other polypeptides but not fibrils or monomers26,27. In the absence of EGCG, dot blot analysis revealed strong A11 signals at 72 and 96 hours, supporting the results by AFM that predominantly oligomeric K18ΔK280 aggregates are spontaneously formed in vitro (Figure 1 E). Interestingly, at 120 hours, the A11 signal decreased, which could be due to the formation of the larger aggregates that are less efficiently recognized by the antibody. In samples of K18ΔK280 co-incubated with EGCG, we observed no time-dependent increase in the A11 signal, suggesting that EGCG inhibits the formation of potentially proteotoxic oligomeric tau species.

Taken together, these data indicate that EGCG is a potent inhibitor of K18ΔK280 aggregation in vitro, which blocks the formation of insoluble, high-molecular weight, SDS-stable tau oligomers at substoichiometric concentrations.

EGCG prevents tau conformational changes and rescues tau toxicity in vitro

Next, we scrutinized the effect of EGCG on the structure of tau K18ΔK280. First, we tested if EGCG bound to the monomer or to some other tau species. After incubation with EGCG (5× molar ratio) we performed SDS-PAGE and detected tau by silver staining and EGCG by electroblotting and subsequent staining with the redox-sensitive dye nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), which detects EGCG-bound polypeptides19,28. As before, treatment with EGCG prevented the formation of SDS-resistant tau dimers, oligomers, or aggregates (Figure 2 A). However, a second (18 kDa) band appeared after 24 h with slightly lower mobility than the tau monomer (16 kDa). This band reacted weakly with silver staining, but strongly with the EGCG-sensitive dye NBT. This suggests that the bulk of the protein exists as a monomer that is not bound to EGCG, but that a subpopulation of EGCG-bound tau molecules exists. These molecules are either monomers that have a conformation that is distinct from the unbound tau monomers, or they are present in the form of SDS-labile oligomers.

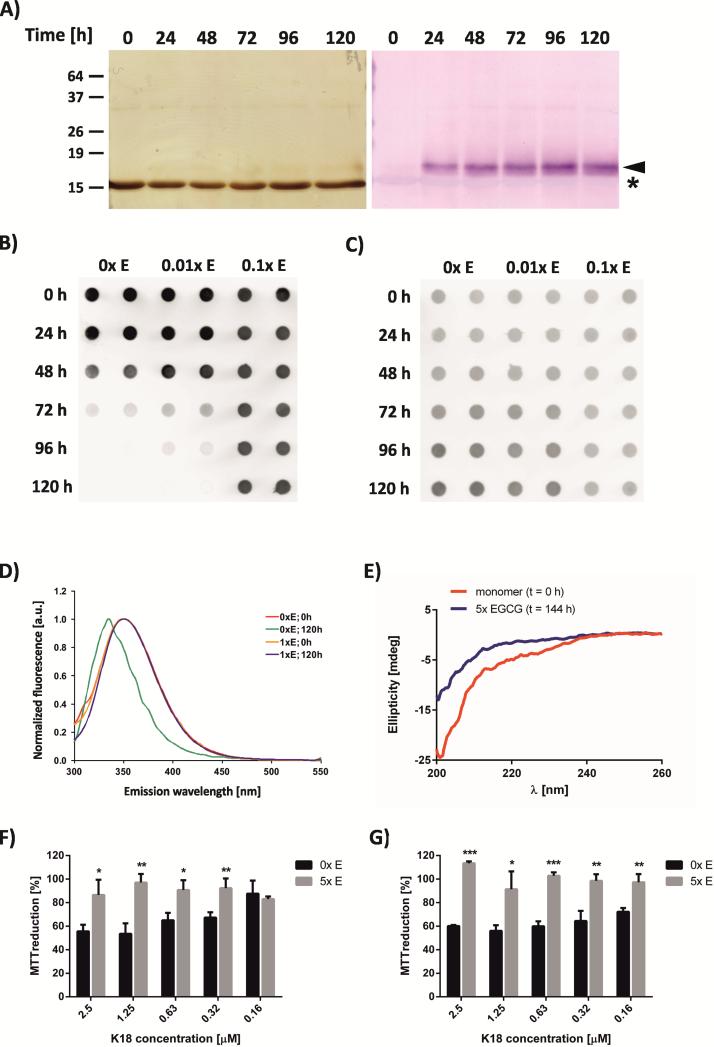

Figure 2. EGCG prevents tau conformational changes and rescues tau toxicity.

A) EGCG binding to K18ΔK280 visualized by NBT staining (right) compared to silver stained protein (left). Asterisk indicates monomer band, arrowhead band stained by NBT. B) Dot blot analysis of non-denatured K18ΔK280 protein incubated in the absence (0×) or presence of substoichiometric (0.01× and 0.1×) concentrations of EGCG for 0 - 120 hours. C) Dot blot analysis of denatured samples of K18ΔK280 incubated under the same conditions. D) Tryptophan fluorescence spectra of K18ΔK280 (12.5 μM) incubated for 0 h or 120 h in the absence or presence of equimolar concentrations of EGCG (tryptophan absorption wavelength 280 nm). E) Circular dichroism spectra of K18ΔK280 (12.5 μM) incubated with EGCG. F), G) Assessment of tau K18ΔK280 toxicity using the MTT metabolic assay. PC-12 cells were incubated with protein incubated in the absence or presence of EGCG for 144 h. E) Protein samples were filtered using a 10 kDa size exclusion filter. F) Samples were pelleted by ultracentrifugation, washed and resuspended in PBS. Results represent means ± s.d. (n = 3). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 (Student's t-test).

To further assess the effects of EGCG on K18ΔK280 misfolding and aggregation, we performed dot blot assays under native conditions using the anti-tau antibody A0024 (Figure 2 B and C). In the absence of EGCG, antibody binding decreased from 48 hours onwards. After 96 hours of incubation, no tau signal could be detected (Figure 2 B). In contrast, the protein could be detected with the A0024 antibody after 96 h or 120 h in samples incubated with EGCG at 1:100 or 1:10 ratios, respectively. Tau was detected in all samples when re-probed with the same antibody under denaturing conditions (Figure 2 C), confirming that the loss of antibody binding indicated a change in secondary and/or tertiary structure during tau aggregation, which was prevented by EGCG treatment.

We speculated that EGCG might prevent early conformational changes in the tau fragment K18ΔK280 that could trigger subsequent aggregation. To investigate this hypothesis, we performed tryptophan fluorescence and circular dichroism spectroscopy (Figure 2 D and E). In the absence of EGCG, the tryptophan fluorescence emission spectrum of monomeric K18ΔK280 (incubation time 0 hours) showed a maximum emission at approximately 350 nm. After 120 hours of incubation, a hypsochromic shift in the emission spectrum was observed, with maximum emission at 335 nm. This shift in emission was abrogated by co-incubation of K18ΔK280 with EGCG, suggesting that EGCG suppresses the conformational changes observed in untreated protein samples. Correspondingly, circular dichroism spectra before and after incubation with EGCG both indicated that the protein was largely unstructured and did not adopt a β-sheet conformation (Figure 2 E).

Finally, we investigated whether EGCG-treated or -untreated tau aggregates are toxic to mammalian cells. To this end, we incubated K18ΔK280 for 144 h in the presence or absence of EGCG and then filtered K18ΔK280 aggregate samples using a 10 kDa filter to remove all small molecules while retaining all tau species. Solutions were then applied to PC-12 cells for 72 hours, and cell viability was measured by MTT reduction (Figure 2 F). Our results showed a significant cellular toxicity of aggregated K18ΔK280, which was rescued by co-incubation of the protein with EGCG. To confirm that tau toxicity and its rescue by EGCG was linked to the aggregation of tau, we pelleted aggregated tau by ultracentrifugation and washed the pellet to remove DTT, EGCG, and soluble tau protein (Figure 2 G). We found that the resuspended aggregates were toxic to PC-12 cells as assessed by the MTT assay, whereas pellets from EGCG-treated samples were neither toxic nor contained any tau protein. This confirmed that tau toxicity was linked to its aggregation and that EGCG prevented the formation of toxic tau aggregates.

Discussion

Alzheimer's disease is characterized by the two aggregated protein species Aβ and tau1,2. While much effort has been put into elucidating the mechanisms of Aβ polymerization, and a large body of evidence exists for a toxic role of Aβ oligomers in AD pathology29–31, studies investigating the aggregation mechanism of the microtubule-associated protein tau have been less numerous. Recently, oligomeric forms of tau isolated from AD brains were found to be potently toxic32,33 and have been discussed as potential targets for therapeutic intervention34–36. The aim of this study was therefore to establish a model for tau oligomerization in vitro, and to investigate the effects of the green tea polyphenol EGCG on tau oligomerization without the help of polyanions.

EGCG has been implicated in several studies as a drug candidate that modulates the aggregation of proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, such as huntingtin, amyloid-beta and α-synuclein19,23. We found that EGCG strongly inhibits tau aggregation even at highly substoichiometric concentrations, suggesting that the compound may target an aggregation intermediate that appears early in the amyloid formation cascade. However, loss of ThT fluorescence by itself is not a reliable marker for a loss of amyloid-like structures37. Several hypotheses could explain the effect of EGCG on ThT fluorescence: (1) EGCG binds to K18ΔK280 without altering aggregation, but displaces ThT; (2) in the presence of EGCG, K18ΔK280 aggregation is redirected into a distinct aggregate species that has no affinity for ThT; (3) EGCG prevents the polymerization of K18ΔK280, so that the protein largely remains in its natively unfolded monomeric form. We will discuss these possible mechanisms in the following paragraphs.

Sedimentation assays indicated that EGCG indeed inhibits polymerization of tau into high molecular weight aggregates; however, they do not exclude the formation of SDS-labile, low-molecular aggregates in the presence of EGCG. We performed atomic force microscopy to investigate whether such aggregates might be formed in the presence of EGCG. Spherical and amorphous aggregates of K18ΔK280 were detectable from 48 hour onwards in the absence of EGCG, but not in its presence, indicating that if such aggregates form in the presence of EGCG, they are rare. The hypsochromic shift in tryptophan fluorescence of tau oligomers and the masking of antibody binding epitopes compared to monomeric protein indicated a structural change during aggregation that was prevented by EGCG. Dot blot analysis using anti-oligomer antibody A11 and circular dichroism spectroscopy further corroborated that EGCG prevents the formation of β-sheet-rich oligomeric tau species.

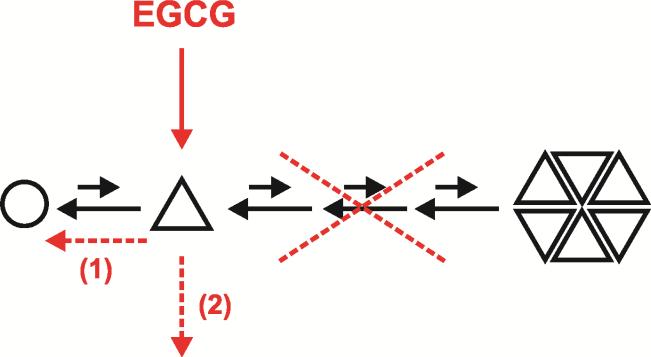

In summary, these data strongly support the hypothesis that EGCG prevents the formation of toxic tau oligomers and keeps the bulk of the tau fragment in a monomeric, unfolded state. In contrast, previous data on Aβ, α-synuclein, and IAPP indicated that EGCG induces a specific conformational change and redirects these polypeptides into off-pathway aggregation14,19. Since EGCG inhibited tau aggregation at highly substoichiometric concentrations, stable, quantitative binding to the tau monomer cannot explain its effect. Rather, we conclude that EGCG binds to a rare partially misfolded monomeric or oligomeric tau species. Quinoid substances such as EGCG can covalently bind proteins28. While the role of covalent modification in the mechanism of EGCG is still debated20,37, the appearance of a distinct population of EGCG-bound tau molecules in SDS gels (Figure 2 A) indicates tight, and possibly irreversible, binding of EGCG to a subpopulation of the tau protein. This suggests a mechanism in which EGCG binds to a rare aggregation nucleus and converts it into an inactive conformation, thus removing its seeding activity.

The apparent difference in mechanism of EGCG between K18ΔK280 polymerization on one hand and Aβ, IAPP and α-synuclein polymerization on the other hand, would then result from the rare occurrence of nucleus formation in tau, when compared to nucleus formation of other polypeptides19,20 (Figure 3). Correspondingly, the effect of EGCG on heparin induced tau aggregation more resembled its effect on Aβ. Here, the lag phase was very short and nucleus formation was not a rare rate-limiting step. Consequently, EGCG had little effect on aggregation kinetics even though it did change the structure of heparin-induced K18ΔK280 aggregates.

Figure 3. Working model for the effects of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate on the aggregation of tau.

In this model, EGCG preferentially binds to a misfolded monomer or a rare transient nucleus (triangle), not to the unfolded monomer (circle). Binding of EGCG to the misfolded monomer or nucleus either catalytically converts it back to its unfolded monomeric form (dashed arrow (1)), or converts it to an inactive conformation and removes it from the aggregation cascade (dashed arrow (2)), thus inhibiting subsequent aggregation steps.

Alternatively, EGCG could transiently bind rare oligomers and catalytically return tau to its unfolded monomeric state, acting as a chemical chaperone38,39. Chemical chaperones have been shown to both stabilize the native conformation of amyloidogenic proteins and to destabilize partially folded states39–41. The presence of tightly bound EGCG-tau complexes and the absence of kinetic inhibition in heparin–induced aggregation both argue against such a mechanism. However, the methods used in our study are not sensitive to conformational changes in small subpopulations of the tau protein, so more refined experiments would be needed to conclusively rule out a catalytic mechanism.

In conclusion, our study indicates that EGCG is a potent inhibitor of tau aggregation and toxicity. Its effect on K18ΔK280 polymerization is distinct from its effects on Aβ and α-synuclein aggregation. Its dual inhibition of both Aβ and tau aggregation into β-sheet rich, toxic structures, might be of synergistic benefit for the treatment of AD.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Tau forms neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease

Four repeat domain tau fragment K18ΔK280 aggregates into toxic oligomers without heparin

EGCG inhibits K18ΔK280 aggregation at ten- to hundred-fold substoichiometric concentrations

EGCG likely sequesters and inactivates a rare nucleating tau oligomer species

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Holzer (Paul Flechsig Institute for Brain Research, University of Leipzig) for providing K18ΔK280 cDNA and A. Otto (Max Delbrueck Center Berlin) for MS measurements. The project was supported by the Nationales Genomforschungsnetz Plus grant 01GS08132 (JB + EW), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant BI1409-1/2 (JB), the Helmholtz-Alliance Helmholtz Alliance for Mental Health in an Ageing Society – HelMA (EW), NINDS grant 1R01NS071835 (MD) and The Tau Consortium.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- EGCG

(−)-epigallocatechin gallate

- ThT

Thioflavin T

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- NBT

nitroblue tetrazolium

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Masters CL, et al. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundke-Iqbal I, et al. Microtubule-associated protein tau. A component of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:6084–6089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosik KS, Joachim CL, Selkoe DJ. Microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) is a major antigenic component of paired helical filaments in Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1986;83:4044–4048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanzi RE, et al. Amyloid beta protein gene: cDNA, mRNA distribution, and genetic linkage near the Alzheimer locus. Science. 1987;235:880–884. doi: 10.1126/science.2949367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giannetti AM, et al. Fibers of tau fragments, but not full length tau, exhibit a cross beta-structure: implications for the formation of paired helical filaments. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 2000;9:2427–2435. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.12.2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goedert M, Ghetti B, Spillantini MG. Tau gene mutations in frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17). Their relevance for understanding the neurogenerative process. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000;920:74–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goedert M, et al. Assembly of microtubule-associated protein tau into Alzheimer-like filaments induced by sulphated glycosaminoglycans. Nature. 1996;383:550–553. doi: 10.1038/383550a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedhoff P, Schneider A, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Rapid assembly of Alzheimer-like paired helical filaments from microtubule-associated protein tau monitored by fluorescence in solution. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 1998;37:10223–10230. doi: 10.1021/bi980537d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barghorn S, et al. Structure, microtubule interactions, and paired helical filament aggregation by tau mutants of frontotemporal dementias. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2000;39:11714–11721. doi: 10.1021/bi000850r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bieschke J. Natural compounds may open new routes to treatment of amyloid diseases. Neurotherapeutics. 2013;10:429–439. doi: 10.1007/s13311-013-0192-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickhardt M, et al. Anthraquinones inhibit tau aggregation and dissolve Alzheimer's paired helical filaments in vitro and in cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:3628–3635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taniguchi S, et al. Inhibition of heparin-induced tau filament formation by phenothiazines, polyphenols, and porphyrins. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:7614–7623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rambold AS, et al. Green tea extracts interfere with the stress-protective activity of PrP and the formation of PrP. J. Neurochem. 2008;107:218–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng F, Abedini A, Plesner A, Verchere CB, Raleigh DP. The flavanol (−)- epigallocatechin 3-gallate inhibits amyloid formation by islet amyloid polypeptide, disaggregates amyloid fibrils, and protects cultured cells against IAPP-induced toxicity. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2010;49:8127–8133. doi: 10.1021/bi100939a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauber I, Hohenberg H, Holstermann B, Hunstein W, Hauber J. The main green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate counteracts semen-mediated enhancement of HIV infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:9033–9038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811827106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreira N, et al. Binding of epigallocatechin-3-gallate to transthyretin modulates its amyloidogenicity. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3569–3576. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferreira N, Saraiva MJ, Almeida MR. Natural polyphenols inhibit different steps of the process of transthyretin (TTR) amyloid fibril formation. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2424–2430. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheynis T, et al. Aggregation modulators interfere with membrane interactions of β2-microglobulin fibrils. Biophys. J. 2013;105:745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehrnhoefer DE, et al. EGCG redirects amyloidogenic polypeptides into unstructured, off-pathway oligomers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:558–566. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao P, Raleigh DP. Analysis of the inhibition and remodeling of islet amyloid polypeptide amyloid fibers by flavanols. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2012;51:2670–2683. doi: 10.1021/bi2015162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh M, Arseneault M, Sanderson T, Murthy V, Ramassamy C. Challenges for research on polyphenols from foods in Alzheimer's disease: bioavailability, metabolism, and cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:4855–4873. doi: 10.1021/jf0735073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh M, et al. Enhancement of cancer chemosensitization potential of cisplatin by tea polyphenols poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2011;7:202. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2011.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bieschke J, et al. EGCG remodels mature alpha-synuclein and amyloid-beta fibrils and reduces cellular toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:7710–7715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910723107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nesterenko MV, Tilley M, Upton SJ. A simple modification of Blum's silver stain method allows for 30 minute detection of proteins in polyacrylamide gels. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 1994;28:239–242. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeVine H. Quantification of beta-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:274–284. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kayed R, et al. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flach K, et al. Tau oligomers impair artificial membrane integrity and cellular viability. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:43223–43233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.396176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paz MA, Flückiger R, Boak A, Kagan HM, Gallop PM. Specific detection of quinoproteins by redox-cycling staining. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shankar GM, et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med. 2008;14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh DM, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lasagna-Reeves CA, et al. Alzheimer brain-derived tau oligomers propagate pathology from endogenous tau. Sci. Rep. 2012;2:700. doi: 10.1038/srep00700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lasagna-Reeves CA, et al. Identification of oligomers at early stages of tau aggregation in Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2012;26:1946–1959. 34. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-199851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Martinez L, Farías GA, Maccioni RB. Tau Oligomers as Potential Targets for Alzheimer's Diagnosis and Novel Drugs. Front. Neurol. 2013;4:167. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castillo-Carranza DL, et al. Passive immunization with Tau oligomer monoclonal antibody reverses tauopathy phenotypes without affecting hyperphosphorylated neurofibrillary tangles. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2014;34:4260–4272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3192-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davidowitz E, Chatterjee I, Moe J. Targeting tau oligomers for therapeutic development for Alzheimer's disease and tauopathies. Curr. Top. Biotechnol. 2008;4:47–64. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palhano FL, Lee J, Grimster NP, Kelly JW. Toward the molecular mechanism(s) by which EGCG treatment remodels mature amyloid fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:7503–7510. doi: 10.1021/ja3115696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cortez L, Sim V. The therapeutic potential of chemical chaperones in protein folding diseases. Prion. 2014;8 doi: 10.4161/pri.28938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ignatova Z, Gierasch LM. Inhibition of protein aggregation in vitro and in vivo by a natural osmoprotectant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:13357–13361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603772103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tatzelt J, Prusiner SB, Welch WJ. Chemical chaperones interfere with the formation of scrapie prion protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:6363–6373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torrente MP, Shorter J. The metazoan protein disaggregase and amyloid depolymerase system: Hsp110, Hsp70, Hsp40, and small heat shock proteins. Prion. 2014;7 doi: 10.4161/pri.27531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.