Abstract

The seventh AJCC TNM classification defines rules for classifying adenocarcinomas of esophagogastric junction (AEG II and III) as a part of esophageal cancer. But there are still many controversies over the classification system. The study aims to evaluate and compare whether AEG should be classified as cancers of esophagus or stomach. A single-center cohort of patients with AEG or proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma underwent surgical resection with curative intent in Shanghai from November 2004 to July 2011. We compared the clinicopathologic features between AEG (n=291) and proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma (n=176) and analyzed overall survival probabilities of AEG using the latest seventh AJCC TNM classification for cancers. Patients with AEG not only show more advanced diseases, but also have a significantly worse 5-year survival rate than those with proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma (P=0.027). In 291 patients with AEG, the gastric T classification is monotone but indistinct except for pT2 versus pT3 (P=0.001) and pT4a versus pT4b (P=0.012). The esophageal T classification is neither monotone nor distinct. For the N classification, both schemes are monotone and distinct. The gastric scheme is indistinctive for stages IA versus IB (P=0.428), for IIA versus IIB (P=0.376), for IIB versus IIIA (P=0.086), for IIIA versus IIIB (P=0.087), and for IIIC versus IV (P=0.928). The esophageal scheme is indistinct only except for IIIB versus IIIC (P=0.002). The gastric scheme includes one heterogeneous stage group (stage IIIC, P<0.001), whereas all stage groups are homogeneous in the esophageal scheme. Although AEG shows different clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of patients, the current seventh AJCC TNM classification which stages the AEG in the esophageal scheme does not demonstrate the advantages in the assessment of the patient prognosis. We propose a revised staging system to clarify the AEG with esophageal invasion.

Keywords: TNM classification, esophagogastric junction, esophageal cancer, gastric cancer

Introduction

The incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (AEG) has been dramatically increasing in the Western countries during the last two decades [1,2]. However, it is not clear whether this trend has also occurred in Eastern countries [3-5]. Like gastric carcinoma, due to the lack of effective preoperative screening, AEG is often diagnosed at an advanced stage. AEG are proposed to be an aggressive disease with different histopathologic entities from adenocarcinoma in other part of stomach, such as poor prognosis, early lymph node metastasis and hematogenous dissemination [6,7].

Siewert’s classification proposed AEG into 3 types according to the sites of the tumor epicenter [8]. The classification was approved at the consensus meetings of the Seventh International Society of Diseases of the Esophagus in 1995 and the second International Gastric Cancer Congress in 1997. But the classification of AEG as either an esophageal or a gastric cancer is still not clear. The recently new seventh edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification firstly converged cancer staging across the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) [9,10]. Accordingly, cancers whose epicenters are within the first 5 cm of the stomach that extend into the EGJ are now staged as esophageal cancers. The other cancers with epicenters within 5 cm of the EGJ but not extending into the EGJ or in the stomach greater than 5 cm from the EGJ are considered as gastric cancers. It means that the Siewert type II AEG (true cardiac carcinoma) and the Siewert type III AEG (subcardial gastric carcinoma that infiltrates the EGJ and the lower esophagus from below) are now assigned to the different staging system for esophageal cancer. Perhaps the newly-approved classification has profound implications for medical treatment, but it still provoked more controversies. Because in the Eastern countries, AEJ has always been considered and treated as a unique group of adenocarcinoma of the proximal third of the stomach. The etiological and pathological characteristics of AEG are different from Eastern and Western countries.

In our retrospective study, we investigated the clinicopathologic characteristics of AEG and proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma and analyzed overall survival probabilities of AEG according to the latest seventh AJCC TNM classification for the cancers to evaluate which of the current staging systems best defines prognosis of these tumors.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 467 patients with AEG or proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma who underwent curative surgical resection at the Department of General Surgery and the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Ren Ji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, School of Medicine, Shanghai, China, from November 2004 to July 2011, were enrolled in this study. Patients who had received neoadjuvant therapy before the surgery, with recurrent cancer, or gastric stump cancer were excluded from this study.

AEG definition

AEG was defined as tumors with epicenters within 5 cm of the anatomical EGJ. The location of the primary cancer was classified by Siewert’s classification. AEG II was defined as a tumor with an epicenter located between 1 cm above and 2 cm below the EGJ; and AEG III was defined as a tumor with an epicenter located below 2 cm from the EGJ. The proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma was ruled out from the AEG. Before the surgery, all the patients underwent thoraco-abdominal computed tomography scan and esophago-gastric endoscopy for tumor staging by Siewert’s subtype protocol. All surgical specimens were delivered to the department of pathology after the operation. The pathologists and endoscopists measured the distance from the EGJ to the tumor’s epicenter and determined the Siewert’s type together. The demographic data of these patients were collected, included gender, age, tumor size, histologic type, numbers of lymph node retrieved and metastatic lymph nodes. Follow-up periods ranged from 2 to 91 months (median 24 months). Overall survival analysis contained all the deaths, including those due to an unrelated cause.

TNM classification

We compared clinicopathologic features and overall survivals between patients with AEG and proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma in order to examine the rationality of the new seventh edition of AJCC TNM classification, which allocates AEG to the separate staging system for esophageal cancer. Meanwhile, the staging systems for esophageal cancer and gastric cancer were both used to describe tumor progression in all patients with AEG II or AEG III. To confirm the reliability of the new staging system, we examined the monotonicity (decreasing patient survival with increasing stage group), distinctiveness (difference in survival between groups) and homogeneity (similar survival within a group). The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ren Ji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, School of Medicine in Shanghai, China.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 11.0 software (Chicago, Illinois). The data were expressed as mean ± SD. Student’s t-test and One-way ANOVA test were used to compare data between the different groups. Survival time was calculated from the month of operation, and the day of death or the month of last follow-up was considered as the endpoint. Survival curves were drawn according to the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was applied to compare the survival curves. Differences were considered significant at P<0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Among the 467 patients analyzed, 127 patients had AEG II, 164 patients had AEG III and 176 patients had proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma. In all, 372 were male (79.7%) and 95 were female (20.3%). The median age was 66 years. Primary surgical resection was performed in all the patients and no patient underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. All these operations in the AEG patients included systematic abdominal D2 lymphadenectomy and lymphadenectomy in the lower mediastinum. The median number of retrieved lymph nodes was 24 (range, 7 to 54). In 426 of the 467 patients (91.2%), 15 or more lymph nodes were resected.

AEG versus proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma

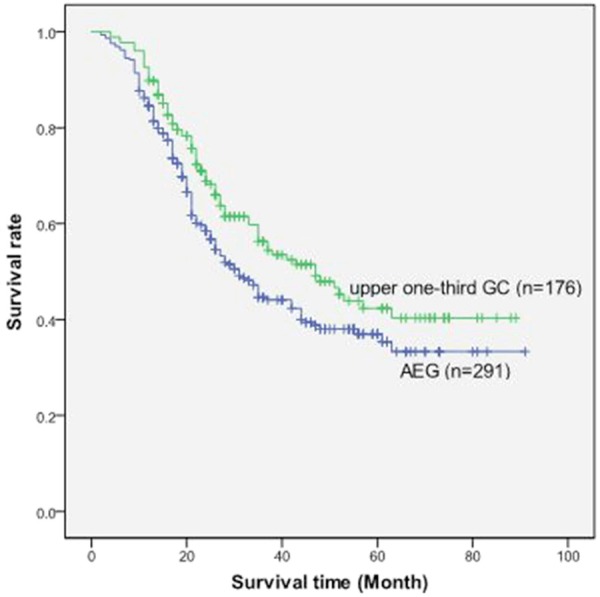

There was no significant difference between AEG and proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma except that AEG showed a larger tumor size, a greater number of retrieved lymph nodes and a higher proportion of advanced T stage (Table 1). The 5-year survival rate of patients with AEG (37%) is significantly poorer than those with proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma (42.4%, P=0.027, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of AEG and proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma

| AEG (n=291) | upper 1/3 GC (n=176) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male:Female) | 236:55 | 136:40 | 0.32 |

| Age (year, Mean±SD) | 65.5±11.7 | 65.6±11.3 | 0.934 |

| Size of tumor (cm, Mean ± SD) | 5.9±2.4 | 4.6±2.6 | <0.001 |

| No. metastatic LN | 4.0±4.8 | 3.5±4.2 | 0.275 |

| No. retrieved LN | 25.8±7.7 | 22.1±7.4 | <0.001 |

| T stage | |||

| T1 | 14 (4.8%) | 20 (11.4%) | 0.008 |

| T2-T4 | 277 (95.2%) | 156 (88.6%) | |

| N stage | |||

| N0 | 89 (30.6%) | 57 (32.4%) | 0.684 |

| N1-N3 | 202 (69.4%) | 119 (67.6%) | |

| Histology | |||

| Differentiated | 184 (63.2%) | 99 (56.3%) | 0.135 |

| Undifferentiated | 107 (36.8%) | 77 (43.8%) |

Figure 1.

Overall survival curve of patients between the group of AEG and the group of proximal third adenocarcinoma.

TNM classification

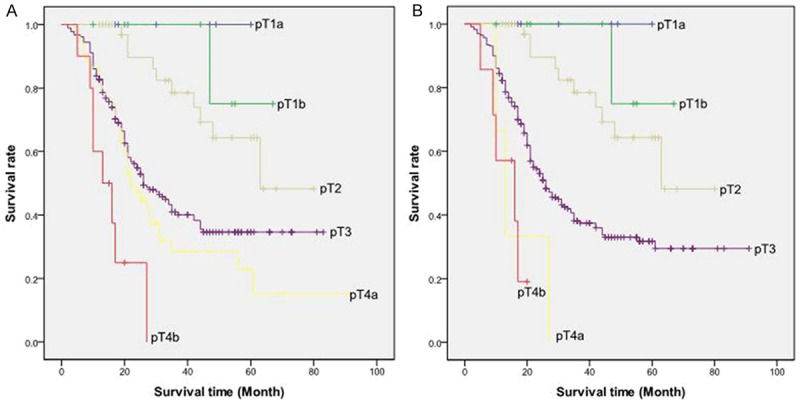

Considering stage distribution by the esophageal and gastric schemes, 55 patients (18.9%) switched their T classification, 64 patients (22.0%) switched their N classification. Figure 2A shows that, for AEG, the gastric T classification was monotone which defined subgroups with continuous decreasing survival with increasing T stage. But it was indistinct except for pT2 versus pT3 (P=0.001) and pT4a versus pT4b (P=0.02) (Table 2), as it lacked significant differences in survival between these T categories. In contrast, the esophageal T classification was neither monotone nor distinct (Figure 2B; Table 2). In addition, the 5-year survival rate for patients staged at pT4a (0%) was worse than that at pT4b (19%). These 2 subgroups are combined into pT4b in the gastric scheme because the T classification for cancer of the stomach does not account for different types of infiltrated adjacent structure. Among the 231 patients staged as pT3 by the esophageal scheme, the gastric scheme classified 179 of them to be pT3, whereas pT4a for the remaining 52 because of perforation of the serosa without infiltration into any adjacent structures.

Figure 2.

A: Overall survival curve of patients with AEG stratified by the seventh AJCC TNM classification for cancers of the stomach according to pT category. B: Overall survival curve of patients with AEG stratified by the seventh AJCC TNM classification for cancers of the esophagus according to pT category.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of patients with AEG stratified by the seventh AJCC TNM classification for cancersof the stomach and esophagus according to pT category

| AJCC stomach | n | 5-year survival (%) | P value between subgroups* | AJCC esophagus | n | 5-year survival (%) | P value between subgroups* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pT1a | 6 | 100% | 0.386 | pT1a | 6 | 100% | 0.386 |

| pT1b | 8 | 75% | 0.382 | pT1b | 8 | 75% | 0.382 |

| pT2 | 36 | 64.3% | 0.001 | pT2 | 36 | 64.3% | <0.001 |

| pT3 | 179 | 34.6% | 0.183 | pT3 | 231 | 31.7% | 0.076 |

| pT4a | 52 | 22.9% | 0.012 | pT4a | 3 | 0 | 0.804 |

| pT4b | 10 | 0 | pT4b | 7 | 19% |

Analysis between the adjacent subgroups according to pT category.

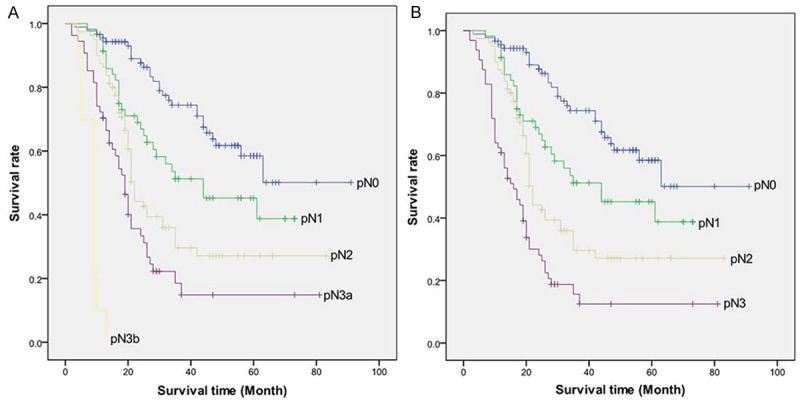

For the N classification, both the gastric and the esophageal schemes were monotone and distinct (Figure 3A, 3B). That is, prognosis decreased with an increasing number of lymph node metastases with statistical differences between all number-based N subgroups. The gastric scheme differentiated between 54 patients with pN3a tumors and 10 patients with pN3b tumors, whereas the esophageal scheme combined all 64 patients with >6 lymph nodes metastases into pN3. The further subclassification of the pN3 group in the gastric scheme revealed statistical differences in prognosis between the pN3a and pN3b patients in our cohort (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Figure 3.

A: Overall survival curve of patients with AEG stratified by the seventh AJCC TNM classification for cancers of the stomach according to pN category. B: Overall survival curve of patients with AEG stratified by the seventh AJCC TNM classification for cancers of the esophagus according to pN category.

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of patients with AEG stratified by the seventh AJCC TNM classification for cancers of the esophagus and stomach according to pN category

| AJCC stomach | n | 5-year survival (%) | P value between subgroups* | AJCC esophagus | n | 5-year survival (%) | P value between subgroups* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pN0 | 89 | 58.5% | 0.014 | pN0 | 89 | 58.5% | 0.014 |

| pN1 | 58 | 45.2% | 0.039 | pN1 | 58 | 45.2% | 0.039 |

| pN2 | 80 | 27.2% | 0.017 | pN2 | 80 | 27.2% | 0.001 |

| pN3a | 54 | 14.8% | <0.001 | pN3 | 64 | 12.5% | |

| pN3b | 10 | 0 |

Analysis between the adjacent subgroups according to pN category.

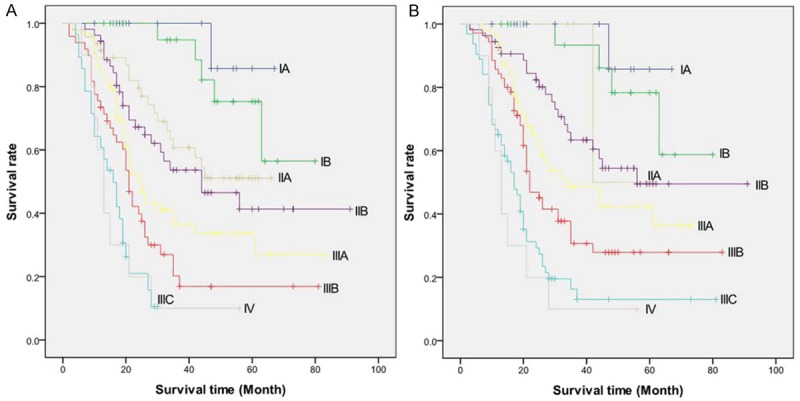

Both staging schemes proved to be monotone but indistinct for all stage groups (Figure 4A, 4B). The gastric scheme was not distinctive for stages IA versus IB (P=0.428), for IIA versus IIB (P=0.376), for IIB versus IIIA (P=0.086), for IIIA versus IIIB (P=0.087), and for IIIC versus IV (P=0.928). The esophageal scheme was all indistinct with only except for IIIB versus IIIC (P=0.002). Moreover, Tables 4 and 5 demonstrate the heterogeneity of some stage groups. The survival rates of patients with different TNM subsets within a stage group differed significantly. In the gastric scheme, all stage groups were homogeneous, except for stage IIIC, with significant differences in survival between the different TNM subsets (P<0.001). Whereas in the esophageal scheme, all stage groups were homogeneous with no significant differences in survival between the different TNM subsets.

Figure 4.

A: Overall survival curve of patients with AEG stratified by the seventh AJCC TNM classification for cancers of the stomach. B: Overall survival curve of patients with AEG stratified by the seventh AJCC TNM classification for cancers of the esophagus.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of patients with AEG stratified by the seventh AJCC TNM classification for cancersof the stomach

| AJCC stomach | Subsets | n | 5-year survival | P value between subsets | P value between stages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IA | pT1aN0M0 | 6 | 100% | 0.386 | |

| pT1bN0M0 | 8 | 75% | |||

| 0.428 | |||||

| IB | pT2N0M0 | 24 | 75.3% | / | |

| 0.04 | |||||

| IIA | pT3N0M0 | 41 | 50.9% | 0.712 | |

| pT2N1M0 | 6 | 60% | |||

| 0.376 | |||||

| pT4aN0M0 | 7 | 40% | |||

| IIB | pT3N1M0 | 40 | 42.8% | 0.45 | |

| pT2N2M0 | 6 | 26.7% | |||

| 0.086 | |||||

| IIIA | pT4aN1M0 | 9 | 51.9% | 0.382 | |

| pT3N2M0 | 57 | 30% | |||

| 0.087 | |||||

| pT4bN0M0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| pT4bN1M0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| IIIB | pT4aN2M0 | 13 | 16.5% | 0.6 | |

| pT3N3aM0 | 31 | 20% | |||

| pT3N3bM0 | 3 | 0 | |||

| 0.027 | |||||

| IIIC | pT4aN3aM0 | 18 | 13% | ||

| pT4aN3bM0 | 3 | 0 | |||

| pT4bN2M0 | 2 | 0 | <0.001 | ||

| pT4bN3aM0 | 2 | 50% | |||

| pT4bN3bM0 | 3 | 0 | |||

| 0.928 | |||||

| IV | anyTanyNM1 | 10 | 10 | / |

Table 5.

Subgroup analysis of patients with AEG stratified by the seventh AJCC TNM classification for cancers of the esophagus

| AJCC esophagus | Subsets | n | 5-year survival | P value between subsets | P value between stages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IA | pT1aN0M0G1-2 | 6 | 100% | 0.386 | |

| pT1bN0M0G1-2 | 8 | 75% | |||

| 0.528 | |||||

| IB | pT2N0M0G1-2 | 19 | 78.3% | / | |

| 0.442 | |||||

| IIA | pT2N0M0G3 | 5 | 50% | / | |

| 0.45 | |||||

| IIB | pT3N0M0 | 48 | 49.2% | 0.788 | |

| pT2N1M0 | 6 | 60% | 0.119 | ||

| IIIA | pT2N2M0 | 6 | 26.7% | 0.79 | |

| pT3N1M0 | 49 | 44.8% | |||

| pT4aN0M0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 0.106 | |||||

| IIIB | pT3N2M0 | 70 | 27.9% | / | |

| 0.002 | |||||

| IIIC | pT3N3M0 | 55 | 13.9% | 0.666 | |

| pT4aN3M0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| pT4bN1M0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| pT4bN2M0 | 2 | 0 | |||

| pT4bN3M0 | 4 | 25% | 0.554 | ||

| IV | anyTanyNM1 | 10 | 10% | / |

Discussion

The distribution of the three types of AEG is strikingly different between Western and Eastern countries. In Eastern countries, Type II and III cancers are more common than type I [11,12]. In Western countries the distribution is more or less the same [13,14]. Theoretically, type I cancer arises from the esophageal glandular epithelium, mostly occur in the Barrett’s esophagus. Type III cancer arises from the gastric mucosa, where might be associated with Helicobacter pylori. However type II cancer is true AEG arising from the junctional epithelium. Most of studies have demonstrated that the entity of type II cancer is more similar to that of type III than that of type I cancer [15]. So in Eastern countries, AEJ has often been considered as a part of adenocarcinoma of the proximal third of the stomach. Type II and type III patients at most Japanese institutions are likely to be treated by the gastric surgical group or the department of general surgery, while those with type I patients are treated by the esophageal surgical group. In China, AEG are always vaguely classified as the cancer of cardia, which could be treated as the cancer of distal esophagus or the proximal gastric cancer by esophageal or gastric surgeons respectively. Therefore, there can be two separate sets of database in Chinese medical institutes. In the present study, we combined and examined databases from the two different departments to clarify the clinical features and outcomes of AEG at a single cancer center hospital in China.

Our study demonstrates that tumor diameter was larger and pathological T stage was more advanced in AEG than in proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma. A larger number of retrieved lymph nodes in AEG than proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma are possibly due to the higher probability of lower mediastinal lymphadenectomy with transthoracic approach. These findings are similar to the recently retrospective analysis from Suh et al. in Korea [16]. The postoperative prognosis, which is the most important determinant for stage grouping, was significantly different for AEG and proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma in our study. Tokunaga et al. also reported the 5-year overall survival rate was significantly better in patients without esophageal invasion than in patients with esophageal invasion [17], while the conclusion by Suh et al. that there was no significant difference in prognosis between gastric carcinoma and AEG did not support our results [16]. It would be more reasonable to consider that the most potential cause of worse AEG prognosis may be the late detection of AEG with their relevant distribution of advanced stage [18]. Meanwhile, the lymphatic metastasis flow from the lower esophagus into the lower mediastinal node could deteriorate the outcome [12,19]. In our study, all patients with AEG II and III received lower mediastinal lymphadenectomy. There was no significant difference in the number of metastatic lymph nodes between AEG and proximal third gastric adenocarcinoma, thus we did not compare the station of metastatic lymph nodes between two groups. Although the value of lower mediastinal lymphadenectomy remains controversial, this could still be the other reason for the poorer prognosis of AEG. Considering risk factors for carcinogenesis, AEG also have some different pathogenesis from gastric cancer. All these could explain why the new seventh TNM classification was proposed for AEG in the esophageal category.

In our study, the gastric T classification proved to be monotone as it defined subgroups with continuous decreasing survival with increasing T stage. But it was not distinct for all T groups, with no significant difference in prognosis between pT1a and pT1b tumors, pT1b and pT2 tumors, pT3 and pT4a tumors. In contrast, the esophageal T classification was neither monotone nor distinct because patients with pT4a disease had an even worse survival than patients with pT4b disease due to the limitation of pT4 patients (n=10). And if we combined pT4a and pT4b into one stage (pT4), the esophageal T classification would be monotone just like the gastric T classification. A retrospective analysis by Gertler et al. from a large German cohort of 1141 patients with AEG II and AEG III demonstrated monotonicity and distinctiveness of the esophageal T classification, while the gastric T classification was only partially monotone but was not distinct across the T groups [20]. The other study by Huang et al. from China with 142 patients failed to show monotonicity and distinctiveness of the gastric T classification, but 88% of Huang’s cohort was consisted of pT3 tumors [21]. Our study also proved significant prognostic differences between pT2 and pT3 tumors in both esophageal and gastric classification. Recently published study from Korea reported the marked different prognosis between gastric pT2 and pT3 tumors [22]. But the data from Germany had the opposing results that there was no prognostic difference between pT2 and pT3 tumors according to the gastric scheme [20]. The problem in gastric T classification is somehow difficult to apply for AEG II because there is no serosa in some parts affected by the tumor.

For the N classification, both schemes were monotone and distinct, an increasing number of lymph node metastases leading to continuously decreasing and significantly different prognosis. The N classification for stomach cancer differed between pN3a and pN3b tumors, revealing statistically significant differences in prognosis between these subgroups. With the similar results from the German study [20], the differentiation of pN3a and pN3b disease is believed to be justified and might be considered in future AJCC esophageal cancer stage groupings.

The new AJCC TNM system of esophageal scheme implanted the histology grade to subclassify T1N0M0 patients into stages IA and IB, T2N0M0 patients into stages IB and IIA. However, the roles of histology grade in AEG patient survival were controversial in the literature. The study including 292 patients with esophageal cancer by Wijnhoven et al. showed histology grade as a prognostic factor in univariate analysis but not in Cox regression multivariate analysis [23]. In present study, there is no significant prognostic difference between stage IB (pT2N0M0G1-2) and IIA (pT2N0M0G3) in esophageal scheme.

Comparing the 2 staging schemes for AEG II and AEG III, we found that only the gastric scheme (IIIC) included one heterogeneous stage group. This stage group included subsets of patients with significantly different survival. Moreover the gastric scheme was not distinctive among the 5 stages, whereas the esophageal scheme was not distinctive among the 6 stages. On the basis of stage heterogeneity and distinctiveness, it seemed that the new AJCC TNM system is not as good for prognostic stratification of patients with AEG II and AEG III when they are grouped as esophageal cancers, compared with when staged as gastric cancers. The other data from China concluded that AEG were better staged by the gastric system than esophageal cancer staging system only by the figures of survival curve and did not present any statistical evidence to favor the gastric scheme [21]. While the data from Germany favored the esophageal over the gastric scheme because there were less heterogeneous and distinctive stage groups in esophageal scheme than those in gastric scheme [20]. All these studies showed that the prognosis of patients with AEG II and AEG III was sufficiently determined by both the gastric and esophageal schemes, but either schemes of the staging system did not reveal clear proficiency. It is easy to acknowledge that an ideal cancer staging should not only provide an indication of prognosis and a framework for treatment decisions but should also allow for evaluation of treatment with meaningful comparisons between different treatments or the same treatment modalities by different groups [24]. It also offers a “common language” for convenient communication between clinicians from different countries. However, the large number of stage groups in both schemes and the complex subgroupings in stage III somehow counteract the principal goal of cancer staging.

In our study, there are certain limitations. First, patients’ surgical procedure and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy may be different between the different departments. Second, our patient cohort is limited in number (n=291) and even there is no patient in some subsets. So it could be difficult to clarify the homogeneity of the staging system.

In conclusion, AEG shows different clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of patients from the gastric cancer. The current seventh AJCC TNM classification which stages the AEG in the esophageal scheme does not show the advantages in the assessment of patient prognosis. Neither of two staging systems is absolutely superior over the other. We hope that our findings will initiate further studies which would need to be designed to propose a revised stage grouping to clarify the AEG with esophageal invasion.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry (20144908).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Devesa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JJ. Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 1998;83:2049–2053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botterweck AA, Schouten LJ, Volovics A, Dorant E, van Den Brandt PA. Trends in incidence of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia in ten European countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:645–654. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shibata A, Matsuda T, Ajiki W, Sobue T. Trend in incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus in Japan, 1993-2001. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:464–468. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kusano C, Gotoda T, Khor CJ, Katai H, Kato H, Taniguchi H, Shimoda T. Changing trends in the proportion of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction in a large tertiary referral center in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1662–1665. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung JW, Lee GH, Choi KS, Kim DH, Jung KW, Song HJ, Choi KD, Jung HY, Kim JH, Yook JH, Kim BS, Jang SJ. Unchanging trend of esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma in Korea: experience at a single institution based on Siewert’s classification. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:676–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saito H, Fukumoto Y, Osaki T, Fukuda K, Tatebe S, Tsujitani S, Ikeguchi M. Distinct recurrence pattern and outcome of adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia in comparison with carcinoma of other regions of the stomach. World J Surg. 2006;30:1864–1869. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0582-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohno S, Tomisaki S, Oiwa H, Sakaguchi Y, Ichiyoshi Y, Maehara Y, Sugimachi K. Clinicopathologic characteristics and outcome of adenocarcinoma of the human gastric cardia in comparison with carcinoma of other regions of the stomach. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:577–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Classification of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1457–1459. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice TW, Rusch VW, Ishwaran H, Blackstone EH Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration. Cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: data-driven staging for the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer Cancer Staging Manuals. Cancer. 2010;116:3763–3773. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice TW, Blackstone EH, Rusch VW. 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1721–1724. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai JG, Lv Y, Dang CX. Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagogastric Junction in China according to Siewert’s classification. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:364–367. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosokawa Y, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, Takahashi S, Gotohda N, Kato Y, Daiko H, Nishimura M, Katsumata K, Sugiyama Y, Kinoshita T. Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction according to Siewert classification: experiences at a single institution in Japan. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:677–683. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1983-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siewert JR, Stein HJ, Feith M. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. Scand J Surg. 2006;95:260–269. doi: 10.1177/145749690609500409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Manzoni G, Pedrazzani C, Pasini F, Di Leo A, Durante E, Castaldini G, Cordiano C. Results of surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siewert JR, Feith M, Stein HJ. Biologic and clinical variations of adenocarcinoma at the esophago-gastric junction: relevance of a topographic-anatomic subclassification. J Surg Oncol. 2005;90:139–146. doi: 10.1002/jso.20218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suh YS, Han DS, Kong SH, Lee HJ, Kim YT, Kim WH, Lee KU, Yang HK. Should adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction be classified as esophageal cancer? A comparative analysis according to the seventh AJCC TNM classification. Ann Surg. 2012;255:908–915. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824beb95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tokunaga M, Tanizawa Y, Bando E, Kawamura T, Tsubosa Y, Terashima M. Impact of esophageal invasion on clinicopathological characteristics and long-term outcome of adenocarcinoma of the subcardia. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:856–861. doi: 10.1002/jso.23152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakaguchi T, Watanabe A, Sawada H, Yamada Y, Tatsumi M, Fujimoto H, Emoto K, Nakano H. Characteristics and clinical outcome of proximal-third gastric cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:352–357. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nunobe S, Ohyama S, Sonoo H, Hiki N, Fukunaga T, Seto Y, Yamaguchi T. Benefit of mediastinal and para-aortic lymph-node dissection for advanced gastric cancer with esophageal invasion. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:392–395. doi: 10.1002/jso.20987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gertler R, Stein HJ, Loos M, Langer R, Friess H, Feith M. How to classify adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction: as esophageal or gastric cancer? Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1512–1522. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182294764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Q, Shi J, Feng A, Fan X, Zhang L, Mashimo H, Cohen D, Lauwers G. Gastric cardiac carcinomas involving the esophagus are more adequately staged as gastric cancers by the 7th edition of the American Joint Commission on Cancer Staging System. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:138–146. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn HS, Lee HJ, Hahn S, Kim WH, Lee KU, Sano T, Edge SB, Yang HK. Evaluation of the seventh American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer Classification of gastric adenocarcinoma in comparison with the sixth classification. Cancer. 2010;116:5592–5598. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wijnhoven BP, Tran KT, Esterman A, Watson DI, Tilanus HW. An evaluation of prognostic factors and tumor staging of resected carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Surg. 2007;245:717–725. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251703.35919.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sayegh ME, Sano T, Dexter S, Katai H, Fukagawa T, Sasako M. TNM and Japanese staging systems for gastric cancer: how do they coexist? Gastric Cancer. 2004;7:140–148. doi: 10.1007/s10120-004-0282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]