Abstract

Epidemiological studies indicate that progestin-containing contraceptives increase susceptibility to HIV, although the underlying mechanisms involving the upper female reproductive tract are undefined. To determine the effects of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) and the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) on gene expression and physiology of human endometrial and cervical transformation zone (TZ), microarray analyses were performed on whole tissue biopsies. In endometrium, activated pathways included leukocyte chemotaxis, attachment, and inflammation in DMPA and LNG-IUS users, and individual genes included pattern recognition receptors, complement components, and other immune mediators. In cervical TZ, progestin treatment altered expression of tissue remodeling and viability but not immune function genes. Together, these results indicate that progestins influence expression of immune-related genes in endometrium relevant to local recruitment of HIV target cells with potential to increase susceptibility and underscore the importance of the upper reproductive tract when assessing the safety of contraceptive products.

Keywords: progestin-based contraceptives, gene expression, endometrium, cervix, host defense

Introduction

Contraceptives are utilized by more than 660 million women worldwide, with hormonal methods accounting for at least 20%.1 In Sub-Saharan Africa, over 8 million use injectable hormonal contraceptives, mainly depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA).1 Intrauterine devices, including the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), are popular and highly effective methods of long-acting reversible contraception, and nonhormonal IUS are used by over 160 million women worldwide.1 Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and the LNG-IUS have complex systemic and local mechanisms of action on the endometrium, ranging from progestational early effects to atrophy with long-term use.2,3 However, epidemiological evidence indicates that DMPA may increase male to female HIV transmission,4 although effects of other long-acting, progestin-only methods have not been evaluated extensively. The mechanisms underlying these epidemiologic observations are unclear.

For male to female HIV transmission, the female reproductive tract (FRT) is a site of viral introduction, and mounting evidence suggests that the endometrium and cervical transformation zone (TZ, zone between the ecto- and endocervix) are potential portals of HIV entry.5,6 In contrast to the lower FRT (vagina and ectocervix), which is lined by a multilayered squamous epithelium,7 the upper FRT (TZ, endocervix, and uterus) consists of a single-layered columnar epithelium. The latter is a major site of mucosal lymphoid tissue and is the first line of defense against pathogens. For example, the upper FRT epithelia secrete innate immune factors, including secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor and defensins, and inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, endometrial cells express the HIV coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5.5,8 In cycling women, progesterone promotes secretory transformation of the endometrium along with an influx of leukocytes, increased production of innate immune factors, and immune tolerance. In the absence of pregnancy and with declining progesterone levels, there is an influx of macrophages and the secretion of inflammatory cytokines locally that promote tissue desquamation and menses.9 Interestingly, the greatest risk of sexual acquisition of HIV is postulated to occur in the secretory phase of the cycle, indicating that progesterone may induce changes in the local immune milieu of the upper FRT that increase this susceptibility.6,10

Although the lower FRT mucosa is the most intensively investigated site of HIV entry in male to female transmission, with numerous in vitro and in vivo studies,11 upper FRT tissues are plausible portals of HIV entry and accessed by fluids deposited intravaginally.5,6,11–15 Understanding upper FRT responses to exogenous progestins is important in the context of a possible role for them in susceptibility to HIV transmission and to better understand how vaccinations and other treatments may function in women. Herein, in a cross-sectional study of DMPA and the LNG-IUS users, we assessed the effects of these progestins on whole-genome transcriptomes of upper FRT tissues. We found moderate changes in cervical TZ and profound changes in the expression of immune-related genes of the endometrium, suggesting that mediators of innate immunity and populations of HIV-susceptible cells may be altered in the upper FRT in vivo by exposure to systemic and local progestins.

Methods

Study Design and Human Tissue Acquisition

This report is based on a cross-sectional study of DMPA and LNG-IUS users and women using no hormonal contraception, all of whom consented to study participation and procedures using a human subjects protection protocol that was approved by the University of California San Francisco Human Subjects Protection Committee. All biopsies were taken for the sole purpose of research, with no other medical indications. Samples were obtained during the mid-secretory phase from the nonhormonal contraception comparison group, 7 to 10 days after a positive home urine luteinizing hormone test (ClearBlue urine Ovulation Test, www.clearblue.com) and verified by a plasma progesterone level on the day of sampling (Table 1).The DMPA and LNG-IUS users were sampled after a minimum of 6 months of method use and did not have phase-based urine sampling. Participants were 18 to 45 years old, with intact uteri, negative HIV serologies and negative urine nucleic acid amplification tests for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and were free from clinically evident vaginitis or other acute infections. Women who donated tissue for the control group did not have a history of abnormal bleeding. Rare spotting occurred in DMPA users and there was variability in spotting/bleeding among LNG/IUS users. Participants were asked to refrain from vaginal intercourse or to use unlubricated condoms for 10 days prior to tissue collection. Women with recent or unresolved cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, current use of steroidal or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, recent pregnancy (within a year), and who were breast-feeding were excluded. All participants had a negative urine pregnancy test on the day of tissue collection. Participants from the nonhormonal contraception comparison group had a history of regular menstrual cycles (21-35 days) and at least 3 normal menstrual cycles since discontinuation of any previous hormonal or intrauterine device contraception.

Table 1.

Participant Information.

| ID# | Group | Age | Cycle Day | Days Post LH Surge | Duration of Use, days | Serum P4 | Endo Bx | Cervix Bx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR-A | Control | 43 | 18 | 7 | N/A | 9.4 | Y | N |

| PR-B | Control | 44 | 21 | 8 | N/A | 9.7 | N | Y |

| PR-C | Control | 28 | 22 | 6 | N/A | 5.9 | N | Y |

| PR-D | Control | 40 | 20 | 7 | N/A | 3.2 | Y | Y |

| PR-E | Control | 43 | 26 | 9 | N/A | 16.6 | Y | Y |

| PR-F | Control | 41 | 19 | 7 | N/A | 6.7 | Y | Y |

| PR-G | Control | 34 | 24 | 8 | N/A | 9.3 | Y | N |

| PR-H | Control | 32 | 20 | 7 | N/A | 9.9 | Y | N |

| PR-I | Control | 26 | 26 | 9 | N/A | 6 | N | Y |

| PR-J | Control | 27 | 18 | 6 | N/A | 6.4 | Y | Y |

| PR-K | Control | 26 | 24 | 8 | N/A | 7.7 | N | Y |

| PR-L | Control | 28 | 21 | 8 | N/A | 9.6 | N | Y |

| PR-M | Control | 43 | 23 | 9 | N/A | 2.5 | Y | Y |

| PR-N | Control | 34 | 21 | 9 | N/A | 16.9 | N | Y |

| PR-O | Control | 27 | 21 | 7 | N/A | 12.4 | N | Y |

| PR-P | Control | 38 | 31 | 8 | N/A | 7.8 | Y | Y |

| PR-01 | Control | 25 | 25 | 8 | N/A | 10.8 | Y | Y |

| PR-02 | Control | 36 | 26 | ND | N/A | 8.8 | N | Y |

| PR-04 | Control | 28 | 24 | 9 | N/A | 7.7 | N | Y |

| PR-08 | Control | 38 | 27 | 11 | N/A | 2.3 | Y | Y |

| PR-09 | Control | 34 | 27 | 11 | N/A | 2.9 | Y | Y |

| PR-13 | Control | 27 | 24 | 12 | N/A | 6.5 | N | Y |

| PR-17 | Control | 43 | 23 | 12 | N/A | 3.9 | N | Y |

| PR-03 | DMPA | 28 | N/A | ND | 462 | N/A | N | Y |

| PR-14 | DMPA | 23 | N/A | ND | 776 | N/A | N | Y |

| PR-15 | DMPA | 24 | N/A | ND | 1019 | N/A | N | Y |

| PR-27 | DMPA | 37 | N/A | ND | 274 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-29 | DMPA | 31 | N/A | ND | 1378 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-30 | DMPA | 24 | N/A | ND | 861 | N/A | N | Y |

| PR-32 | DMPA | 26 | N/A | ND | 811 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-33 | DMPA | 32 | N/A | ND | 3251 | N/A | N | Y |

| PR-34 | DMPA | 27 | N/A | ND | 431 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-37 | DMPA | 38 | N/A | ND | 449 | N/A | N | Y |

| PR-38 | DMPA | 23 | N/A | ND | 386 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-40 | DMPA | 32 | N/A | ND | 369 | N/A | N | Y |

| PR-42 | DMPA | 21 | N/A | ND | 1503 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-43 | DMPA | 22 | N/A | ND | 421 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-44 | DMPA | 23 | N/A | ND | 250 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-05 | LNG-IUS | 28 | N/A | ND | 299 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-06 | LNG-IUS | 24 | N/A | ND | 464 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-07 | LNG-IUS | 28 | N/A | ND | 1019 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-10 | LNG-IUS | 21 | N/A | ND | 308 | N/A | N | Y |

| PR-11 | LNG-IUS | 23 | N/A | ND | 272 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-12 | LNG-IUS | 25 | N/A | ND | 400 | N/A | Y | Y |

| PR-18 | LNG-IUS | 32 | N/A | ND | 578 | N/A | N | Y |

| PR-19 | LNG-IUS | 30 | N/A | ND | 1313 | N/A | N | Y |

| PR-20 | LNG-IUS | 28 | N/A | ND | 745 | 0.5 | Y | Y |

| PR-22 | LNG-IUS | 27 | N/A | ND | 803 | 11.9 | N | Y |

| PR-23 | LNG-IUS | 26 | N/A | ND | 408 | 2.6 | N | Y |

| PR-25 | LNG-IUS | 18 | N/A | ND | 755 | 3.4 | Y | Y |

| PR-26 | LNG-IUS | 26 | N/A | ND | 231 | 0.5 | Y | Y |

| PR-31 | LNG-IUS | 40 | N/A | ND | 758 | 0.5 | Y | Y |

| PR-35 | LNG-IUS | 23 | N/A | ND | 443 | 12.1 | Y | Y |

| PR-36 | LNG-IUS | 23 | N/A | ND | 520 | <0.5 | Y | Y |

| PR-39 | LNG-IUS | 44 | N/A | ND | 311 | 9.3 | Y | N |

| PR-41 | LNG-IUS | 26 | N/A | ND | 242 | 0.7 | Y | Y |

Abbreviations: LH, luteinizing hormone; Y, yes; N, no; DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system; N/A, not available; ND, not determined.

Tissue Collection

Endometrial tissues were collected using Pipelle aspirators (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, Connecticut). After 1 to 2 sampling insertions, tissue samples were expelled into Nunc cryovials (Roskilde, Denmark) and flash frozen in acetone and dry ice. Cervical TZ tissues were collected via punch method, placed in a Nunc vial, and flash frozen.

Systemic Progesterone Levels

Plasma progesterone was measured in control samples collected on the day of tissue collection by coated tube assays (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Los Angeles, California) performed by the University of Virginia National Institutes of Health Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research Ligand Assay and Analysis Core (Table 1).

RNA Isolation and Complementary DNA Microarray

RNA was extracted from frozen tissues using Trizol Reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, New York) and purified using the NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania) as described.16 Total RNA as well as protein (A260/A280) and organic compound (A260/A230) contamination were measured using the Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts). Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California) was used to verify that RNA quality met the minimum criteria for array-based complementary DNA (cDNA) generation. Samples were further processed for hybridization to the Affymetrix whole-genome Human Gene 1.0 ST arrays at the Gladstone Institutes Genomics Core according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Affymetrix, Inc, Santa Clara, California) as described.17

Gene Expression Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

The .cel data files were uploaded to the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus Database (Series Accession GSE60129). For each sample, intensity values for all probe sets in the GeneChip operating software (Affymetrix) were imported into GeneSpring GX version 12.6 (Agilent Technologies) and processed using the robust multiarray analysis algorithm for background adjustment, normalization, and log2 transformation of perfect match values.9,18 Intensity values in each condition and tissue type were normalized to the median of all samples. Gene lists were generated using two-way analysis of variance and Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction for false discovery rate and filtered with a ≤1.5-fold change cutoff and P ≤ .05. Principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering were performed as described previously.9,18

Fluidigm-Based Microfluidic Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction Validation of DE Genes

For progestin versus control comparisons, differential expression validation by quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (q-RT-PCR) was performed (TZ: 17 genes DMPA and 13 LNG-IUS; endometrium: 52 DMPA and 69 LNG-IUS). Primers (Supplemental Table 1) were purchased (Fluidigm Corp, South San Francisco, California) and cDNAs reserved from the microarray (endometrium: 7 control, 12 LNG-IUS, and 9 DMPA; cervix: 7 control, 13 LNG-IUS, and 12 DMPA) were enriched for these targets according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, primers were pooled and combined with 250 ng cDNA and TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix (Applied BioSystems, Grand Island, New York), then amplified with Stratagene Mx3005P (Agilent Technologies). Products were treated with USB 10 un/uL exonuclease I (Affymetrix) and diluted 1:20. According to the manufacturer’s protocol, sample and assay mixtures were added to 48.48 (TZ) or 96.96 (endometrium) Dynamic Array IFC chips, loaded with the integrated fluidic circuits (IFC) controllers and run with the BioMark HD system (Fluidigm Corp). Data were imported to Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington), and ΔΔ CT values, average fold change, and standard deviation were calculated. Outliers were removed using Dixon Q test.19

Gene Ontology and Pathway Analyses

Gene ontology and functional annotations were evaluated using Ingenuity Pathway analysis (IPA; Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, California), into which RefSeq IDs and fold changes of differentially expressed genes in each comparison were imported. Inhibition or activation of pathways were predicted for functional groups of genes based on collective messenger RNA expression levels, and significance was determined using the right-tailed Fisher exact test. The P values reflected the number of analysis-specific genes in a given pathway compared with the total number of occurrences of these genes in all pathways in the Ingenuity knowledge base. Results are shown for pathways with a bias-corrected Z score (reported as z=) <−1.0 or >1.0 (except for upstream regulators in cervix DMPA); however, only Z scores < −2.0 or > 2.0 (P < .05) were predicted to be inhibited or activated, respectively.

Correlation Between q-RT-PCR and Microarray Data

The correlation between microarray and q-RT-PCR differential gene expression was evaluated with nonparametric Spearman ρ and Kendall τ tests using StatView 5.0.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina). For both tests, a more positive value indicates greater agreement between microarray and q-RT-PCR differential expression values. The P values were based on a 2-tailed null hypothesis of no association.

Results

Principal Component Analysis and Hierarchical Clustering of Endometrial and Cervical Samples

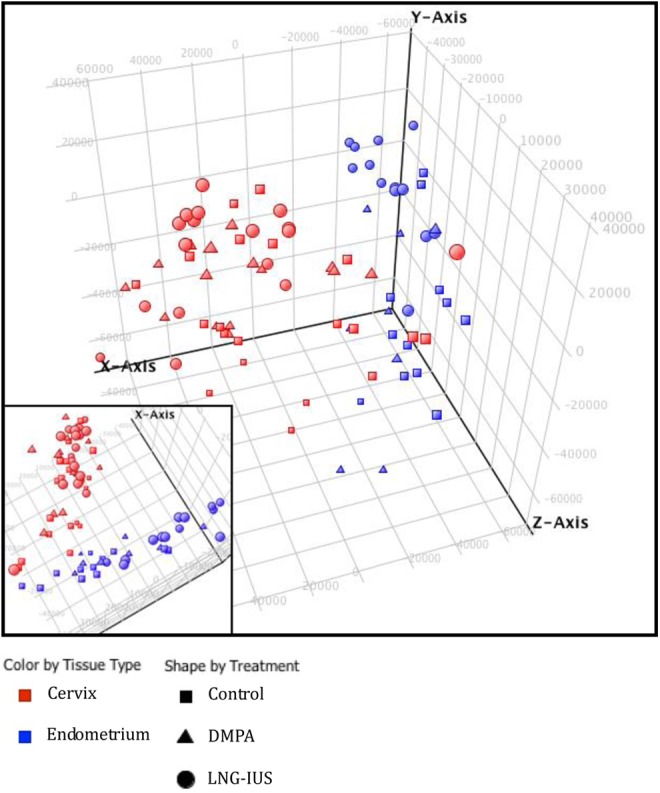

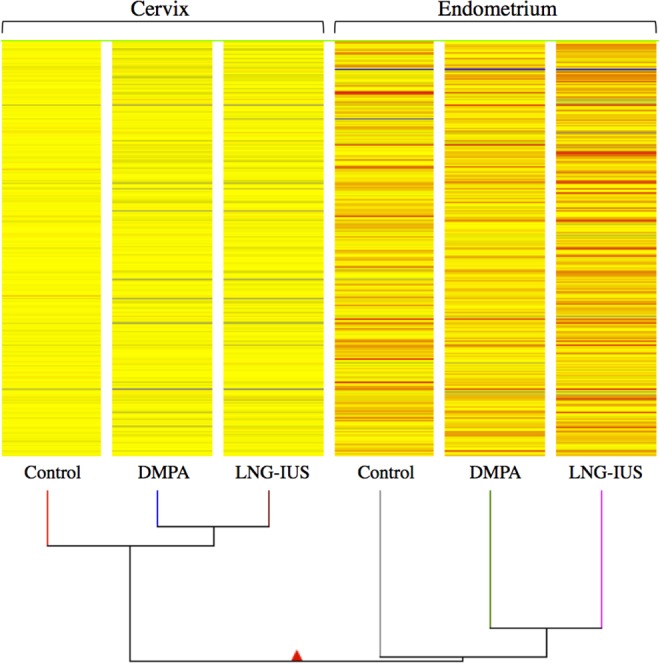

The PCA revealed that samples clustered into 2 major subdivisions, endometrium and cervix (Figure 1). In general, control samples from each tissue clustered more closely with each other than did progestin-treated ones. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analyses based on the combined gene list fold change (FC > 1.5, P < .05) derived from pairwise comparisons yielded a dendrogram of sample clustering and a heatmap of gene expression. The clustergram (Figure 2), similar to the PCA, revealed a main branching between endometrium and cervix and subbranches between controls and progestin-treated samples in the same tissue.

Figure 1.

Principal component analysis.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical clustering.

Effects of Progestins on Endometrial Gene Expression

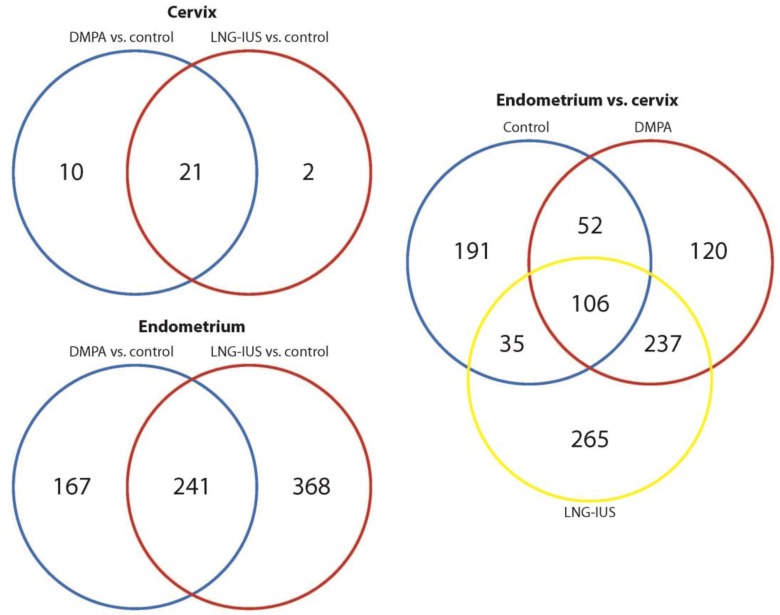

Gene expression comparisons were made between endometrial tissue from women using 1 of the 2 target progestin contraceptives and controls during the mid-secretory (peak progesterone) phase. With DMPA versus control, somatostatin (SST), matrix metallopeptidase 7 (MMP7), and hemoglobin β (HBB) were the genes that demonstrated the greatest increase in expression, and matrix metallopeptidase 26 (MMP26), uroplakin 1B (UPK1B), and hydroxysteroid 17-β dehydrogenase 2 (HSD17B2) were the genes that showed the greatest reduction in expression. With LNG-IUS, IGFBP1, MMP7, and prolactin (PRL) demonstrated the greatest increase in expression, and homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase (HGD), MMP26, and UPKB1 had the largest decrease in expression. High expression of IGFBP1 and PRL and LEFTY2 with both progestins confirmed the progestational effects of these drugs.3,20 In total, there were 609 genes in LNG-IUS and 408 in DMPA which were differentially expressed when compared to tissues from unexposed women. There were 241 genes associated with treatment with either progestin, and 368 and 167 genes unique to LNG-IUS and DMPA, respectively, versus the unexposed controls (Figure 3). Full lists of differentially expressed genes are given in Supplemental Table 2A and B, and those with q-RT-PCR-validated expression levels are given in Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 3.

Venn diagrams.

Table 2.

Correlation of Array and q-RT-PCR: Endometrium DMPA Versus Control.a,b

| Gene | Array | qRT-PCR | Gene | Array | qRT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SST | 11.07 | 82.16 | AQP9 | 1.65 | 6.72 |

| MMP7 | 8.25 | 6.29 | CNR1 | 1.57 | 9.13 |

| S100A8 | 4.19 | 2.55 | TIMP3 | 1.56 | 2.4 |

| IGFBP1 | 3.96 | 152 | CCL3 | 1.56 | 1.68 |

| PROM1 | 3.70 | −1.14 | GZMB | 1.51 | 1.81 |

| LGR5 | 3.64 | 1.35 | SPP1 | 1.50 | 1.93 |

| MMP3 | 3.50 | 12.62 | SERPINA5 | −1.59 | −1.4 |

| IGF2|INS-IGF2 | 3.11 | 2.06 | PAPPA|PAPPAS | −1.61 | −3.1 |

| TNFRSF11B | 3.05 | 6.04 | GPX2 | −1.63 | −4.49 |

| PRL | 2.99 | 3.38 | ICA1 | −1.75 | −2.41 |

| ITGB3 | 2.55 | 4.57 | CTNNA2 | −1.87 | −2.38 |

| MMP1 | 2.53 | 52.27 | PLCB1 | −1.90 | −2.37 |

| LEFTY2 | 2.39 | 7.33 | TLR3 | −1.93 | −4.61 |

| FMOD | 2.26 | 3.12 | FN1 | −2.07 | −1.19 |

| TREM1 | 2.25 | 10.39 | TLR4 | −2.08 | −6.96 |

| RGS2 | 2.22 | 2.07 | HLA-DOB|TAP2 | −2.14 | −11.77 |

| FCGR3A | 2.13 | 3.29 | RHOU | −2.19 | −1.97 |

| C3 | 2.10 | −1.03 | GNG11 | −2.20 | −5.24 |

| WNT5A | 1.97 | 1.82 | PLCB4 | −2.27 | −4.06 |

| FCER1G | 1.96 | 1.52 | CYP26A1 | −2.88 | −4.95 |

| CD163 | 1.84 | 2.72 | FGF10 | −2.91 | −11.07 |

| WNT7A | 1.84 | 5.21 | OGN | −3.16 | −8.03 |

| CCL4 | 1.82 | 1.69 | TFPI2 | −3.59 | −2.3 |

| CCL3L1|CCL3L3 | 1.79 | 3.42 | HGD | −4.87 | −9.78 |

| SERPINE1 | 1.72 | 3.94 | HSD17B2 | −5.63 | −24.43 |

| PRF1 | 1.69 | 1.37 | MMP26 | −7.29 | −12.33 |

Abbreviations: q-RT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate.

aSpearman’s ρ: 0.82, P < .0001.

bKendall τ: 0.62, P < .0001.

Table 3.

Correlation of Array and q-RT-PCR: Endometrium LNG-IUS Versus Control.a,b

| Gene | Array | qRT-PCR | Gene | Array | qRT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGFBP1 | 12.33 | 495 | CD97 | 2.24 | 2.44 |

| MMP7 | 11.72 | 13.5 | MMP3 | 2.22 | 18.75 |

| PRL | 10.22 | 19.7 | CD180 | 2.19 | 1.71 |

| S100A8 | 10.15 | 20.62 | MMP1 | 2.16 | 24.48 |

| TREM1 | 9.57 | 25.52 | CXCR1 | 2.14 | 12.4 |

| SST | 6.26 | 57 | PLAU | 2.11 | 2.21 |

| SERPINE1 | 6.23 | 15.11 | CCL7 | 2.07 | 123.2 |

| AQP9 | 6.20 | 38.6 | CCRL2 | 2.04 | 4.56 |

| CNR1 | 5.55 | 76.7 | CCL24 | 1.88 | 69.38 |

| CD163 | 5.15 | 4.75 | PROM1 | 1.88 | 1.26 |

| HSD11B1 | 4.71 | 132.5 | VEGFA | 1.79 | 1.99 |

| FCGR3A | 4.32 | 4.42 | MMP2 | 1.79 | 2.04 |

| CCL3L1|CCL3L3 | 4.06 | 5.43 | SERPING1 | 1.65 | 1.27 |

| CCL4 | 3.99 | 3.42 | NFKB1 | 1.62 | 1.38 |

| CCL3 | 3.95 | 5.42 | WNT7A | 1.53 | 7.26 |

| RGS2 | 3.89 | 4.64 | GPX2 | −1.57 | −2.64 |

| FCER1G | 3.61 | 3.24 | S100A14 | −1.62 | −1.65 |

| MARCO | 3.43 | 741 | RHOU | −1.65 | −1.62 |

| CCR1 | 3.13 | 3.03 | LGR5 | −1.90 | −2.7 |

| IGF2|INS-IGF2 | 3.04 | 2.04 | HLA-DOB|TAP2 | −2.06 | −3.26 |

| FMOD | 2.99 | 3.9 | TLR3 | −2.15 | −2.58 |

| TIMP3 | 2.95 | 2 | GNG11 | −2.21 | −2.43 |

| ITGAM | 2.95 | 4.09 | ICA1 | −2.36 | −3.27 |

| CD86 | 2.90 | 9.67 | OGN | −2.38 | −4.83 |

| C3 | 2.87 | 1.22 | CTNNA2 | −2.60 | −2.88 |

| GZMB | 2.77 | 2.01 | PLCB1 | −2.64 | −3.83 |

| ITGB3 | 2.70 | 2.95 | CYP26A1 | −2.68 | −2.56 |

| PAPPA|PAPPAS | 2.64 | 2.75 | PLCB4 | −2.72 | −4.28 |

| SPP1 | 2.54 | 1.86 | FGF10 | −2.75 | −5.66 |

| TNFRSF11B | 2.46 | 10.08 | SERPINA5 | −3.56 | −7.82 |

| WNT5A | 2.46 | 3.08 | TFPI2 | −3.91 | −2.11 |

| CD300A | 2.38 | 3.59 | HSD17B2 | −4.78 | −12.73 |

| PRF1 | 2.32 | 3.06 | MMP26 | −7.07 | −17.02 |

| LEFTY2 | 2.27 | 4.06 | HGD | −9.30 | −10.8 |

| MIR223 | 2.25 | 20.34 |

Abbreviations: q-RT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system.

aSpearman’s ρ: 0.79, P < .0001.

bKendall τ: 0.62, P < .0001.

Pathway Analysis: Effects of DMPA

In the endometrium of DMPA users, IPA predicted increased movement of myeloid cells (z = 3.40), adhesion of immune cells (z = 2.35), and inflammatory response (z = 3.68), among other pathways (Table 4). Upstream regulators include TWIST1 (z = 2.00), tumor necrosis factor (TNF; z = 1.62), nuclear factor κ-B (NFκB) complex (z = 1.41), and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL1RN; z = −2.00; Table 5).

Table 4.

Biofunctions: Endometrium DMPA and LNG-IUS Versus Control.

| # Molecules | Z score | Predicted Activity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMPA versus control | |||

| Cell movement | |||

| Chemotaxis of leukocytes | 12 | 3.68 | Increased |

| Cell movement of myeloid cells | 14 | 3.40 | Increased |

| Cell movement of phagocytes | 14 | 3.38 | Increased |

| Cell movement of neutrophils | 8 | 2.63 | Increased |

| Cell movement of granulocytes | 10 | 3.21 | Increased |

| Cell movement of mononuclear leukocytes | 11 | 2.00 | Increased |

| Cell-to-cell signaling and interaction | |||

| Adhesion of immune cells | 11 | 2.35 | Increased |

| Activation of leukocytes | 14 | 1.19 | – |

| Molecular transport | |||

| Quantity of Ca2+ | 10 | 1.65 | – |

| Flux of Ca2+ | 7 | 1.84 | – |

| Metabolism of reactive oxygen species | 8 | 2.01 | Increased |

| Production of reactive oxygen species | 6 | 1.80 | – |

| Inflammatory response | |||

| Inflammatory response | 14 | 3.68 | Increased |

| Tissue development | |||

| Vasculogenesis | 12 | 2.01 | Increased |

| Proliferation of endothelial cells | 10 | 1.99 | – |

| Development of epithelial tissue | 11 | 2.08 | Increased |

| LNG-IUS versus control | |||

| Cell movement | 89 | 2.15 | Increased |

| Homing of cells | 41 | 3.35 | Increased |

| Cell movement of leukocytes | 49 | 3.06 | Increased |

| Cell movement of phagocytes | 32 | 3.57 | Increased |

| Cell movement of myeloid cells | 30 | 3.56 | Increased |

| Cell movement of granulocytes | 19 | 3.11 | Increased |

| Cell movement of monocytes | 17 | 2.27 | Increased |

| Cell movement of neutrophils | 16 | 3.73 | Increased |

| Cell-to-cell signaling and interaction | |||

| Adhesion of immune cells | 26 | 2.97 | Increased |

| Binding of phagocytes | 11 | 2.88 | Increased |

| Binding of T lymphocytes | 5 | 2.24 | Increased |

| Activation of cells | 38 | 1.62 | – |

| Cellular growth and proliferation | |||

| Cell death of connective tissue cells | 13 | −1.85 | – |

| Free radical scavenging | |||

| Synthesis of reactive oxygen species | 14 | 2.20 | Increased |

| Metabolism of reactive oxygen species | 15 | 2.56 | Increased |

| Molecular transport | |||

| Quantity of Ca2+ | 17 | 2.08 | Increased |

| Accumulation of cyclic AMP | 7 | −2.25 | Decreased |

| Cellular growth and proliferation | |||

| Proliferation of endothelial cells | 17 | 2.07 | Increased |

| Cardiovascular system development and function | |||

| Development of blood vessel | 29 | 2.02 | Increased |

| Cellular function and maintenance | |||

| Engulfment of cells | 14 | 2.02 | Increased |

| Tissue development | |||

| Development of epithelial tissue | 21 | 1.67 | – |

Abbreviations: DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system; AMP, adenosine monophosphate.

Table 5.

Upstream Regulators: Endometrium DMPA and LNG-IUS Versus Control.

| Upstream Regulator | Molecule Type | # Molecules | Z Score | Predicted Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMPA vs control | ||||

| TWIST1 | Transcription regulator | 4 | 2.00 | Activated |

| TNF | Cytokine | 19 | 1.62 | – |

| NFκB (complex) | Complex | 6 | 1.41 | – |

| IL10 | Cytokine | 7 | 1.34 | – |

| IL18 | Cytokine | 4 | 1.30 | – |

| LDL | Complex | 4 | 1.29 | – |

| P38 MAPK | Group | 6 | 1.01 | – |

| Immunoglobulin | Complex | 4 | 1.00 | – |

| IL13 | Cytokine | 9 | −1.67 | – |

| IL1RN | Cytokine | 4 | −2.00 | Inhibited |

| LNG-IUS vs control | ||||

| TNF | Cytokine | 37 | 3.93 | Activated |

| NFκB (complex) | Complex | 16 | 3.54 | Activated |

| P38 MAPK | Group | 14 | 3.26 | Activated |

| IL1B | Cytokine | 19 | 2.87 | Activated |

| ERK1/2 | Group | 8 | 2.80 | Activated |

| IFNA2 | Cytokine | 7 | 2.62 | Activated |

| IL2 | Cytokine | 7 | 2.60 | Activated |

| TLR7 | Transmembrane receptor | 7 | 2.60 | Activated |

| IFNG | Cytokine | 21 | 2.47 | Activated |

| TWIST1 | Transcription regulator | 6 | 2.45 | Activated |

| Jnk | Group | 6 | 2.43 | Activated |

| RNASE1* | Enzyme | 5 | 2.22 | Activated |

| IL15 | Cytokine | 5 | 2.22 | Activated |

| MIF | Cytokine | 5 | 2.19 | Activated |

| TREM1* | Transmembrane receptor | 17 | 2.18 | Activated |

| RNASE2 | Enzyme | 8 | 2.15 | Activated |

| IL1A | Cytokine | 4 | 2.00 | Activated |

| TSLP | Cytokine | 4 | 1.98 | – |

| CSF2 | Cytokine | 8 | 1.97 | – |

| CD40LG | Cytokine | 4 | 1.97 | – |

| CTGF | Growth factor | 4 | 1.97 | – |

| EGFR | Kinase | 4 | 1.96 | – |

| TCR | Complex | 14 | 1.95 | – |

| CCL5 | Cytokine | 7 | 1.89 | – |

| IL17A | Cytokine | 6 | 1.75 | – |

| TLR2 | Transmembrane receptor | 6 | 1.66 | – |

| IL18 | Cytokine | 8 | 1.62 | – |

| Cg | Complex | 9 | 1.59 | – |

| STAT3 | Transcription regulator | 11 | 1.58 | – |

| IL4 | Cytokine | 10 | 1.53 | – |

| Immunoglobulin | Complex | 8 | 1.41 | – |

| IL13 | Cytokine | 22 | 1.41 | – |

| LDL | Complex | 6 | 1.38 | – |

| TGFB1 | Growth factor | 13 | 1.35 | – |

| IL6 | Cytokine | 5 | 1.34 | – |

| IL10 | Cytokine | 18 | 1.18 | – |

| IL21 | Cytokine | 8 | 1.13 | – |

| IL3 | Cytokine | 4 | 1.07 | – |

| Hsp27 | Group | 4 | 1.00 | – |

| CD3 | Complex | 8 | −1.07 | – |

| miR-155-5p | Mature microrna | 4 | −1.98 | – |

| COL18A1 | Other | 9 | −2.36 | Inhibited |

| IL1RN | Cytokine | 7 | −2.65 | Inhibited |

Abbreviations: DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system.

Pathway Analysis: Effects of LNG-IUS

In the endometrium of LNG-IUS users, pathway analysis suggested an increase in cell movement of myeloid cells (z > 3.00), engulfment of cells (z = 2.02), and binding of phagocytes (z = 2.88) and T lymphocytes (z = 2.24). Pathways related to blood vessel development (z = 2.02) and synthesis and metabolism of reactive oxygen species (z = 2.20, 2.56) were also activated (Table 4). Upstream regulators that were significantly activated included TNF (z = 3.93), NFκB complex (z = 3.54), P38 MAPK (z = 3.26), and IL1B (z = 2.87) among several others (Table 5).

Validation and Correlation Between Microarray and q-RT-PCR

Differentially expressed genes of interest from endometrium (52 DMPA vs control, 69 LNG-IUS vs control) were chosen and Fluidigm DELTAgene assays were performed starting from the same total RNAs used for the microarray. For each comparison, average fold changes were calculated and correlation analyses were performed using 2 nonparametric measures of correlation, Spearman ρ, and Kendall τ, for DMPA versus control (ρ = 0.82, P < .0001; τ = 0.62, P < .0001) and LNG-IUS versus control (ρ = 0.79, P < .0001; τ = 0.62, P < .0001; Tables 2 and 3).

Effects of DMPA and LNG-IUS on Cervical TZ

The cervical transformation is an important site of cell-mediated immunity.21 When compared with unexposed controls, there were 31 genes differentially expressed with DMPA and 23 genes in LNG-IUS compared with unexposed controls. Between the 2 treatments, there were 21 genes that shared changes in expression, and 10 and 2 genes whose expression was unique to DMPA and LNG-IUS, respectively (Figure 3). In DMPA users, the GABAA receptor pi (GABRP) and 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase [NAD+] (HPGD) were the genes that showed the greatest increase in expression, while MMP7 and complement component 3 (C3) were the genes that showed the largest decline in expression. With LNG-IUS, HPGD had the greatest increase in expression, followed by COX7B and GABRP, while C3 and prominin 1 (PROM1) were the most downregulated. Full lists of differentially expressed genes are given in Supplemental Table 2C and D, and those with q-RT-PCR-validated expression levels are given in Table 6.

Table 6.

Correlation of Array and q-RT-PCR: Cervix DMPA and LNG-IUS Versus Control.a,b

| DMPA Versus Control | LNG-IUS Versus Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Array | qRT-PCR | Gene | Array | qRT-PCR |

| GABRP | 3.03 | 4.04 | HPGD | 2.14 | 5.27 |

| HPGD | 2.44 | 2.34 | COX7B | 1.69 | 1.31 |

| S100A14 | 1.79 | 1.13 | GABRP | 1.69 | 1.47 |

| CLDN8 | 1.58 | 1.94 | S100A14 | 1.66 | 1.29 |

| SERPING1 | −1.55 | −1.22 | CLDN8 | 1.54 | 2.78 |

| TIMP1 | −1.61 | −1.14 | PTGER2 | −1.62 | −1.02 |

| LOX | −1.63 | −2.25 | FN1 | −1.64 | −1.39 |

| CFTR | −1.63 | −1.22 | SPP1 | −1.75 | −1.21 |

| HGD | −1.64 | −1.34 | IL1R1 | −1.77 | −1.03 |

| FMOD | −1.65 | −1.55 | MMP2 | −1.77 | −1.44 |

| IL1R1 | −1.70 | −1.72 | SERPING1 | −1.84 | −1.15 |

| SPP1 | −1.78 | −1.53 | C3 | −1.94 | 1.20 |

| FN1 | −1.78 | −1.68 | PROM1 | −2.09 | 1.63 |

| MMP2 | −1.87 | −1.57 | |||

| C3 | −1.93 | −1.02 | |||

| MMP7 | −1.93 | −1.24 | |||

| PROM1 | −2.42 | −1.03 | |||

Abbreviations: q-RT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system; DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate.

aSpearman’s ρ: 0.49, P = .48; Spearman’s ρ: 0.46, P = .11.

bKendall τ: 0.38, P = .039; Kendall τ: 0.33, P = .11.

Pathway Analysis: Effects of DMPA

In the cervical TZ of DMPA users, pathway analysis indicates the occurrence of increased necrosis (z = 2.04) and decreased proliferation of cells (z = −2.30). A trend toward decreased expression of genes involved with adhesion of blood cells (z = −1.20) was also found (Table 7). A trend toward the decreased expression of TNF genes (z = −0.17) was identified but was not statistically significant (Table 8).

Table 7.

Biofunctions: Cervix DMPA and LNG-IUS Versus Control.

| # Molecules | Z Score | Predicted Activity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMPA vs control | |||

| Cell death | |||

| Necrosis | 5 | 2.04 | Increased |

| Apoptosis | 5 | 1.31 | – |

| Cell death | 6 | 1.30 | – |

| Cell-to-cell signaling and interaction | |||

| Adhesion of blood cells | 4 | −1.20 | – |

| Cellular growth and proliferation | |||

| Proliferation of cells | 9 | −2.30 | Decreased |

| LNG-IUS vs control | |||

| Cellular movement | |||

| Migration of cells | 6 | −1.01 | – |

| Cell-to-cell signaling and interaction | |||

| Adhesion of blood cells | 4 | −1.44 | – |

| Cellular growth and proliferation | |||

| Proliferation of cells | 7 | −2.42 | Decreased |

Abbreviations: DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system.

Table 8.

Upstream Regulators: Cervix DMPA and LNG-IUS Versus Control.

| Upstream Regulator | Molecule Type | # Molecules | Z Score | Predicted Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMPA vs control | ||||

| TNF | cytokine | 6 | −0.17 | – |

| LNG-IUS vs control | ||||

| TNF | cytokine | 4 | −1.15 | – |

Abbreviations: DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system.

Pathway Analysis: Effects of LNG-IUS

In TZ of LNG-IUS users, the expression of genes involved in the proliferation of cells was significantly decreased (z = −2.42), and there was a trend toward decreased expression of genes involved in the adhesion of blood cells (z = −1.44) and migration of cells (z = −1.01; Table 7). As with DMPA, a trend indicating a decrease in genes involved with TNF was identified, but the effect did not reach statistical significance (z = −1.15; Table 8).

Validation and Correlation Between Microarray and q-RT-PCR

Differentially expressed genes of interest from cervix (17 DMPA vs control, 13 LNG-IUS vs control) were chosen and Fluidigm DELTAgene assays were performed starting from the same total RNA extracts used for the microarray. Average fold changes were calculated and correlation analyses were performed using Spearman ρ and Kendall τ tests, for DMPA versus control (ρ = 0.49, P = .048; τ = 0.38, P = .039) and LNG-IUS versus control (ρ = 0.46, P = .11; τ = 0.33, P = .11; Table 6).

Endometrium Versus Cervix: Differential Expression of Genes and Pathway Analyses

The current study also offered the opportunity to study the biology of the TZ that was exposed to different progestins and compare its response to that of the endometrium. Analyses of endometrium versus cervix for DMPA, LNG-IUS, or no treatment were performed. There were 384 differentially expressed genes for no treatment, 515 for DMPA, and 643 for LNG-IUS. In all, 106 genes were common to all 3 groups, while DMPA and LNG-IUS shared 237, DMPA shared 52 with control, and LNG-IUS shared 35 with control (Figure 3). In all analyses, IGFBP1 was upregulated in endometrium. For DMPA and LNG-IUS, PRL, osteopontin (SPP1), fibronectin 1 (FN1), MMP7, and TIMP3 were also among the most upregulated genes in endometrium (Supplemental Table 2E-G). Genes related to cell movement of leukocytes, inflammatory response, and cell death were modified in endometrium of women using DMPA and LNG-IUS but not in the no-contraceptive group. In cervix, compared with endometrium, pathways related to infectious disease including replication of HIV-1 (z = −2.26 for DMPA, −1.64 for LNG-IUS) and infection of T-lymphocytes (z = −2.05, −1.41) were decreased as was cell death of connective tissue cells (z = −1.34, −1.34; Supplemental Table 3). Several upstream regulators were also found to be altered in each treatment (Supplemental Table 4).

Discussion

Progestins Alter Immune Milieu

Our findings herein demonstrate that administration of the progestin-based contraceptives DMPA and LNG-IUS alters the immune milieu of the endometrium, with key pathways governing recruitment of immune cells and immune response being differentially expressed. The pathways we have identified are consistent with studies demonstrating chemokine alterations and increased numbers of leukocytes, including macrophages, in endometrium of subdermal LNG, LNG-IUS, MPA, or norethisterone users.22,23 The current study comprises the first global gene expression profile of upper FRT tissues in women using progestin-based contraceptives, and the accompanying analysis provides insight into possible mechanisms for the increased rates of HIV infection observed for users of progestin contraceptives in some studies.

Although the cervical TZ is commonly considered to be vulnerable to HIV,21,24 an appreciable change in immunologically or structurally relevant gene expression in response to progestins was not detected in our work. In contrast, both progestins induced profound changes in endometrial tissue, influencing the expression of cytokines and chemokines, markers of monocyte-derived cells, pattern recognition receptors, and components of the complement system. Together the data indicate that DMPA and LNG-IUS use may increase susceptibility to HIV infection via the recruitment of HIV target cells and a reduced antiviral response by these cells in the endometrium.

Global and Progestational Effects of LNG-IUS and DMPA on Endometrium

In this study, the changes in expression of several genes were consistent with the expected action of both progestins on the endometrium. The high concentration of LNG released directly into the uterine cavity, as well as mechanical effects of the IUS contacting the uterus, may have resulted in the larger number of genes that demonstrated differential expression and the greater extent of the changes in expression found in endometrial tissues compared with tissues taken from users of DMPA, which is systemically and not locally administered. Upregulation of IGFBP1 and PRL, key markers of endometrial stromal decidualization,25–27 is consistent with their upregulation in stromal fibroblasts exposed to progestins.28 There was also marked downregulation of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (HSD17B2), which converts estradiol E2 to the less active estrone E1, an effect previously shown with progestin use.29

Interestingly, a study published by another group analyzed the effects of an inert intrauterine device on endometrial gene expression and reported a profile very different from our own.30 Although several genes did overlap between the 2 studies, the direction of the change was not necessarily the same. These differences may indicate that the local hormonal effect overrides, or interacts with, the effect of the foreign substance in the uterus.

Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate and LNG-IUS Induce Expression of Genes Associated With Leukocyte Targeting to the Endometrium

Although CD4 T cells are a primary target in productive HIV infection, antigen presenting cells (APCs) that are concentrated at vulnerable mucosal sites are believed to be initial sites of viral replication.31,32 Dendritic cells (DCs) populate the cervicovaginal squamous epithelium as well as intraepithelial and submucosal sites of the endocervix and endometrium.33,34 In many cases, these cells extend processes through columnar epithelium to probe for foreign antigen.35 Thus, they may be the first point of contact for HIV and are central to viral dissemination to the underlying tissue. Both macrophages and DC may be infected by HIV at low frequencies and even in the absence of infection can transfer virus to T cells through direct contact,36,37 a process aided by expression of CD4, CCR5, and other HIV-binding receptors on both cell types.33,38 In the current study, progestin users demonstrated pathways related to increased myeloid cell migration and binding in the endometrium, as well as increased expression of myeloid cellular markers, lending support to the idea that these cells may contribute to an increased risk of HIV acquisition in progestin users.

During the secretory phase of normally cycling endometrium, an increase in uterine natural killer cells, macrophages, mature DC, and neutrophils, but not B or T lymphocytes, has been observed.39 In the current study, for both DMPA and LNG-IUS compared with mid-secretory phase unexposed controls, changes in expression of genes involved in lymphocyte chemotactic pathways were not found, with differentially expressed genes predominantly predicted to increase myeloid cell chemotaxis and adhesion (Table 4). In particular, there was an increase in the expression of macrophage and DC markers, including CD14 and CD163, suggesting increased numbers of these cells in the endometrium of progestin users.

Interestingly, in the DMPA versus control analysis, inflammatory response was one of the upregulated pathways. Although the effects of progestins are widely thought to be anti-inflammatory, it is important to note the context in which these responses occur. During the progesterone-mediated secretory phase, a variety of leukocytes are recruited to the endometrium during the window of implantation by endometrial epithelial, stromal, and resident leukocyte-secreted chemokines and cytokines, such as interleukin (IL) 6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFA).40 These cells participate in a variety of functions: Decidual NK cells secrete angiogenic factors necessary for a vascularized decidua.41 Studies in mice have shown that endometrial DCs promote a cytokine profile in endometrium that is necessary for successful decidualization.42 Both cells are major facilitators of the innate immune response, and studies (including our results) indicating that progestins promote an inflammatory, chemotactic effect is consistent with events occurring in vivo. Th2 T regulatory cells, which suppress the immune system to promote immunotolerance of the implanting embryo, are also recruited to endometrium, and hence the “anti-inflammatory” response that has been classically proposed as the effect of progesterone/progestins on the endometrium.43 Dendritic cells, in addition to decidualization, have also been shown to play a part in this type of immunosuppression.44 That immune cells are recruited to the endometrium during the secretory phase, mimicking an inflammatory response to infection and that the milieu that the recruited cells generate is anti-inflammatory (because those cells suppress the immune system to inhibit allogenic responses to the implanting embryo) underscore interpretation of the type of inflammatory response elicited by progesterone and synthetic progestins. Furthermore, progestins may elicit cellular responses that differ from progesterone per se and contribute to the results observed herein.

Genes Involved in Microbial Recognition and Antiviral Response are Altered in Endometrium of DMPA and LNG-IUS Users

Pattern recognition receptors such as C-type lectins, scavenger receptors, CD14, and toll-like receptors (TLRs) are crucial mediators of antimicrobial responses in APCs. Strikingly, genes for many of these receptors were differentially expressed in response to progestins (Table 9), including decreased TLR3 with both progestins, downregulation of TLR4 with DMPA, and upregulation of TLR8 with LNG-IUS. Expression of the HIV-enhancing DC-SIGN (CD209) and mannose receptor (MRC1; CD206), expressed on dendritic cells or macrophages residing within the uterine luminal epithelium,34 was also increased with LNG-IUS.

Table 9.

Select Differentially Expressed Genes Listed by Category.

| Gene | Regulation | Fold change (array) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMPA | LNG-IUS | ||

| Pattern recognition receptors | |||

| CD14 | Up | 1.86 | 3.81 |

| CLEC12A | Up | 1.54 | |

| CLEC2D | Up | 2.06 | 2.57 |

| DC-SIGN | Up | 1.56 | |

| MARCO | Up | 3.43 | |

| MRC1|MRC1L1 | Up | 3.83 | |

| MSR1 | Up | 2.19 | 3.15 |

| SCARA3 | Up | 1.70 | |

| TLR3 | Down | −1.93 | −2.15 |

| TLR4 | Down | −2.08 | |

| TLR8 | Up | 1.76 | |

| Complement components | |||

| C2 | CFB | Up | 1.53 | |

| C3 | Up | 2.10 | 2.87 |

| CR1 | Up | 2.23 | |

| ITGAM (CR3) | Up | 2.95 | |

| ITGAX (CR4) | Up | 1.78 | 3.25 |

| SERPING1 | Up | 1.65 | |

| Metallopeptidases and inhibitors | |||

| ADAM19 | Up | 1.68 | |

| ADAMTS2 | Up | 1.76 | |

| ADAMTS5 | Up | 1.74 | |

| ADAMTS8 | Down | −1.85 | −1.62 |

| MMP1 | Up | 2.53 | 2.16 |

| MMP16 | Down | −1.57 | |

| MMP19 | Up | 2.26 | |

| MMP2 | Up | 1.79 | |

| MMP26 | Down | −7.29 | −7.07 |

| MMP3 | Up | 3.50 | 2.22 |

| MMP7 | Up | 8.25 | 11.72 |

| TIMP1 | Up | 2.69 | |

| TIMP3 | Up | 1.56 | 2.95 |

| TIMP4 | Up | 1.56 | |

| Cytokines and receptors | |||

| CCL24 | Up | 1.88 | |

| CCL3 | Up | 1.56 | 3.95 |

| CCL3L1 | CCL3L3 | Up | 1.79 | 4.06 |

| CCL4 | Up | 1.82 | 3.99 |

| CCL7 | Up | 2.07 | |

| CCL8 | Up | 2.47 | |

| CCR1 | Up | 3.13 | |

| CCRL2 | Up | 2.04 | |

| CMKLR1 | Up | 1.93 | |

| CSF1 | Up | 1.71 | |

| CSF2RA | Up | 1.67 | |

| CXCL3 | Up | 1.52 | |

| CXCR1 | Up | 2.14 | |

| IL2RA | Up | 1.58 | |

| TNFRSF11B | Up | 3.05 | 2.46 |

Abbreviations: DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system.

The complement system is an important mediator of innate and adaptive immune responses, activation of which leads to attraction of macrophages and neutrophils and ultimately lysis or phagocytosis of pathogens. Work by our group and others has shown that expression of complement components in the endometrium is regulated by steroid hormones.9,45 Interestingly, C3 and the α integrin component of CR4 (ITGAX; CD11c) were upregulated with DMPA and LNG-IUS, herein, and CR1, CR2, C1 inhibitor (SERPING1), and the α integrin of CR3 (ITGAM; CD11b) were upregulated with LNG-IUS. Although the biological implications of complement component expression in women using progestin contraceptives are not yet fully understood, these data raise important issues about HIV uptake and systemic spread via lymphoid tissue.

Genes Regulating Vascular Development are Differentially Expressed in Endometrium of DMPA and LNG-IUS Users

With both progestins, there were changes in multiple genes predicted by IPA to increase blood vessel development and endothelial cell proliferation (Table 4), including several MMPs, members of the ADAMTS family, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), and SERPINE1 (endothelial plasminogen activator inhibitor, PAI-1). With LNG-IUS, levels of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) also increased. Some of these changes have been previously described and are associated with abnormal bleeding in progestin users.46–48 In combination with other pathways described herein, increased vascularization in the endometrium is a potential route of virus dissemination to the general circulation.

Global and Progestogenic Effects of LNG-IUS and DMPA on Cervix

In cervical TZ, more genes and higher fold changes were observed with DMPA than LNG-IUS. Local release of LNG in the endometrium may explain the lesser effect in the cervix, whereas systemic DMPA could access this tissue more readily. Nonetheless, gene expression changes overlapped considerably between DMPA and LNG-IUS, attesting to their similar mechanisms of action. Interestingly, GABAA receptor pi (GABRP) was among the most highly upregulated genes after exposure to either progestin. Differential expression of genes related to tissue structure is reminiscent of changes occurring during pregnancy with progesterone treatment,49 cervical softening and ripening.50,51 In DMPA users, genes for lysyl oxidase (LOX), fibromodulin (FMOD), FN, SPP1, and MMP2 and MMP-7 were downregulated, suggesting coordinated tissue reorganization. Some of these same genes were downregulated with LNG-IUS as well. Indeed, progesterone and progestins have been used to effectively prevent preterm labor in some populations,52–54 possibly by inhibiting cervical ripening,55 a process characterized by extracellular matrix reorganization. Few human studies have looked at the role of steroid hormones in cervical ripening biochemically; however, expression of estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor correlate with collagen and proteoglycan composition between nonpregnant, term and postpartum cervix.56 Collagen synthesis by cultured human cervical fibroblasts is decreased in response to progesterone, an effect partially abrogated by mifepristone.57 Overall, these data support a transcriptional response in the cervix of DMPA and LNG-IUS users, and future studies should aim to better define these changes in the context of HIV.

Gene Expression in Response to DMPA and LNG-IUS Suggests Reduced Proliferation and Viability of Cells in Cervical TZ

In contrast to effects observed in endometrium, exposure to DMPA or LNG-IUS had little effect on the transcription of immune-related genes in the cervix, although reduced expression of genes implicated in the adhesion of blood cells was suggested for both. Pathways related to cellular proliferation were decreased and in DMPA pathways involved in tissue necrosis were increased; however, these predictions were made based on fairly small changes in the expression of a small number of genes. In addition, expression of HPGD was upregulated in response to both DMPA and LNG-IUS. Under hormonal control,58,59 HPGD degrades prostaglandin E2, a vasoactive compound that attracts immune cells to the cervix during ripening.60,61 Thus, HPGD upregulation is consistent with leukocyte efflux from the cervix. A recent study found that, in contrast to the leukocyte influx that occurs in labor,62,63 MPA reduces macrophage and neutrophil populations in the pregnant mouse cervix.55 Based on these data, it is unlikely that an influx of HIV target cells to the cervix can explain increased susceptibility to HIV following progestin use. However, this does not preclude changes in localization, activation, or viability of cells within the cervix. Given the regulation of genes related to tissue remodeling of the cervical TZ, these other mechanisms are worthy of further investigation.

Progestins Induce Pathways of Tissue Remodeling and Immune Activation in Endometrium Compared With Cervix

In DMPA or LNG-IUS users, pathways regulating cell death, proliferation, and motility and adhesion of leukocytes were found to be increased in endometrium compared with cervix. For women not using progestins, fewer differences were found between the 2 tissues. This can be seen in the PCA, as control samples from each tissue cluster more closely to each other. These data suggest that endometrium but not cervix responds profoundly to both progestins. Interestingly, expression of genes in pathways related to viral infection including replication of HIV-1 was decreased in the endometrium of controls, based on expression of cytokines such as CCL3 and CCL4 in both progestins and TLR-4 and -8 with DMPA. These findings indicate that cervical TZ has a limited transcriptional response to progestins, and in contrast with endometrium, cervical tissue may be more susceptible to HIV in the absence of exogenous progestins.

Limitations to Interpretation of the Study

This study provides a global transcriptomic analysis of endometrium and cervix in vivo in women using progestin contraceptives. Although a minimum of 6 months progestin use was required for participation in the study, due to a small sample size, we did not analyze the effects of exposure time on gene expression; however, we think it is important to investigate this variable in the future.

Given that this was a whole tissue study, it is difficult to draw conclusions about cell-specific responses in these tissues. To address this, we have begun in vitro studies whereby isolated cells are treated with biologically relevant levels of both MPA and LNG to elucidate cell-specific responses relevant to HIV infection. In addition, we are in the process of validating immunological changes to upper FRT tissues, including populations of HIV-target cells, using flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, and protein quantification.

Summary

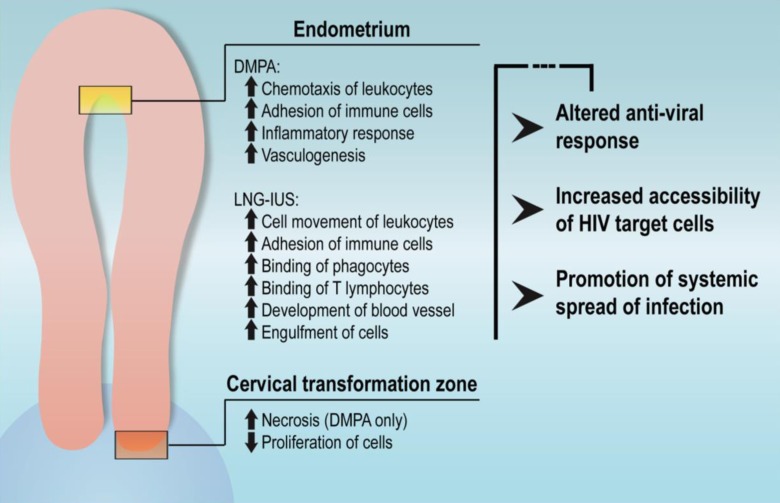

By performing microarray analysis on cervical and endometrial tissues of women using the progestin-based contraceptives DMPA and LNG-IUS, we have provided a global assessment of progestin-induced and repressed gene expression changes in the upper FRT. In addition, we have identified potential immunological alterations in the endometrium that are pertinent to known modes of mucosal HIV infection, including recruitment of HIV-susceptible cells, dampening of innate antiviral mechanisms, and increased vascularization of the tissue (Figure 4). In the cervical TZ, genes related to tissue reorganization were modified in a stereotyped manner, although few changes in the immune milieu were observed. Together, these findings lead us to emphasize the need for further examination of progestin-induced responses in upper FRT tissues in the context of HIV infection.

Figure 4.

Summary and implications of pathways regulated by progestins in endometrium and transformation zone (TZ).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr Barbara Shacklett and Dr Warner Greene for their valuable input; Rebecca Wong for clinical research coordination; Linda Ta and Yanxia Hao (Gladstone Institutes Genomics Core) for technical skills regarding microarray processing; Florence Ng for technical support for Fluidigm analysis and the Biomark system; and the participants of this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Supported by NIH/NIAID P01 grant # AI083050-05, and the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards NIH/NICHD grant # 1F32HD074423-02 (to J.C.C.).

Supplemental Material: The online supplemental Tables are available at http://rs.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- 1. Nations U. World Contraceptive Use 2009. In: contracept2009_wallchart_front.pdf, ed. New York: United Nations Population Division; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guttinger A, Critchley HO. Endometrial effects of intrauterine levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2007;75 (6 suppl):S93–S98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Song JY, Fraser IS. Effects of progestogens on human endometrium. Obst Gynecol Surv. 1995;50 (5):385–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Polis CB, Curtis KM. Use of hormonal contraceptives and HIV acquisition in women: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13 (9):797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rodriguez-Garcia M, Patel MV, Wira CR. Innate and adaptive anti-HIV immune responses in the female reproductive tract. J Reprod Immunol. 2013;97 (1):74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wira CR, Fahey JV. A new strategy to understand how HIV infects women: identification of a window of vulnerability during the menstrual cycle. AIDS. 2008;22 (15):1909–1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patton DL, Thwin SS, Meier A, Hooton TM, Stapleton AE, Eschenbach DA. Epithelial cell layer thickness and immune cell populations in the normal human vagina at different stages of the menstrual cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183 (4):967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shacklett BL, Greenblatt RM. Immune responses to HIV in the female reproductive tract, immunologic parallels with the gastrointestinal tract, and research implications. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65 (3):230–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Talbi S, Hamilton AE, Vo KC, et al. Molecular phenotyping of human endometrium distinguishes menstrual cycle phases and underlying biological processes in normo-ovulatory women. Endocrinology. 2006;147 (3):1097–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saba E, Origoni M, Taccagni G, et al. Productive HIV-1 infection of human cervical tissue ex vivo is associated with the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6 (6):1081–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hladik F, Hope TJ. HIV infection of the genital mucosa in women. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009;6 (1):20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barnhart KT, Stolpen A, Pretorius ES, Malamud D. Distribution of a spermicide containing Nonoxynol-9 in the vaginal canal and the upper female reproductive tract. Hum Reprod. 2001;16 (6):1151–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dayal MB, Wheeler J, Williams CJ, Barnhart KT. Disruption of the upper female reproductive tract epithelium by nonoxynol-9. Contraception. 2003;68 (4):273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang Z. Sexual Transmission and Propagation of SIV and HIV in Resting and Activated CD4+ T Cells. Science. 1999;286 (5443):1353–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Asin SN, Fanger MW, Wildt-Perinic D, Ware PL, Wira CR, Howell AL. Transmission of HIV-1 by primary human uterine epithelial cells and stromal fibroblasts. J Infect Dis. 2004;190 (2):236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aghajanova L, Tatsumi K, Horcajadas JA, et al. Unique transcriptome, pathways, and networks in the human endometrial fibroblast response to progesterone in endometriosis. Biol Reprod. 2011;84 (4):801–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Piltonen TT, Chen J, Erikson DW, et al. Mesenchymal stem/progenitors and other endometrial cell types from women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) display inflammatory and oncogenic potential. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98 (9):3765–3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aghajanova L, Horcajadas JA, Weeks JL, et al. The protein kinase A pathway-regulated transcriptome of endometrial stromal fibroblasts reveals compromised differentiation and persistent proliferative potential in endometriosis. Endocrinology. 2010;151 (3):1341–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dixon W. Analysis of Extreme Values. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21 (4):488–506. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richards RG, Brar AK, Frank GR, Hartman SM, Jikihara H. Fibroblast cells from term human decidua closely resemble endometrial stromal cells: induction of prolactin and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 expression. Biol Reprod. 1995;52 (3):609–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pudney J, Quayle AJ, Anderson DJ. Immunological microenvironments in the human vagina and cervix: mediators of cellular immunity are concentrated in the cervical transformation zone. Biol Reprod. 2005;73 (6):1253–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jones RL, Morison NB, Hannan NJ, Critchley HO, Salamonsen LA. Chemokine expression is dysregulated in the endometrium of women using progestin-only contraceptives and correlates to elevated recruitment of distinct leukocyte populations. Human reproduction. 2005;20 (10):2724–2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Song JY, Russell P, Markham R, Manconi F, Fraser IS. Effects of high dose progestogens on white cells and necrosis in human endometrium. Hum Reprod. 1996;11 (8):1713–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Myer L, Wright TC, Jr, Denny L, Kuhn L. Nested case-control study of cervical mucosal lesions, ectopy, and incident HIV infection among women in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33 (11):683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gellersen B, Brosens J. Cyclic AMP and progesterone receptor cross-talk in human endometrium: a decidualizing affair. J Endocrinol. 2003;178 (3):357–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bell SC, Jackson JA, Ashmore J, Zhu HH, Tseng L. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 synthesis and secretion by progestin and relaxin in long term cultures of human endometrial stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;72 (5):1014–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhu HH, Huang JR, Mazella J, Rosenberg M, Tseng L. Differential effects of progestin and relaxin on the synthesis and secretion of immunoreactive prolactin in long term culture of human endometrial stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71 (4):889–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brar AK, Frank GR, Richards RG, et al. Laminin decreases PRL and IGFBP-1 expression during in vitro decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. J Cell Physiol. 1995;163 (1):30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Burton KA, Henderson TA, Hillier SG, et al. Local levonorgestrel regulation of androgen receptor and 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 expression in human endometrium. Hum Reprod. 2003;18 (12):2610–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Horcajadas JA, Sharkey AM, Catalano RD, et al. Effect of an intrauterine device on the gene expression profile of the endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91 (8):3199–3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wilkinson J, Cunningham AL. Mucosal transmission of HIV-1: first stop dendritic cells. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7 (12):1563–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Morrow G, Vachot L, Vagenas P, Robbiani M. Current concepts of HIV transmission. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4 (1):29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hirbod T, Kaldensjo T, Broliden K. In situ distribution of HIV-binding CCR5 and C-type lectin receptors in the human endocervical mucosa. PLoS One. 2011;6 (9):e25551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kaldensjo T, Petersson P, Tolf A, Morgan G, Broliden K, Hirbod T. Detection of intraepithelial and stromal Langerin and CCR5 positive cells in the human endometrium: potential targets for HIV infection. PLoS One. 2011;6 (6):e21344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rescigno M, Urbano M, Valzasina B, et al. Dendritic cells express tight junction proteins and penetrate gut epithelial monolayers to sample bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2001;2 (4):361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pope M, Gezelter S, Gallo N, Hoffman L, Steinman RM. Low levels of HIV-1 infection in cutaneous dendritic cells promote extensive viral replication upon binding to memory CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182 (6):2045–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rinaldo CR. HIV-1 Trans Infection of CD4(+) T Cells by Professional Antigen Presenting Cells. Scientifica (Cairo). 2013;2013:164203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kawamura T, Gulden FO, Sugaya M, et al. R5 HIV productively infects Langerhans cells, and infection levels are regulated by compound CCR5 polymorphisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100 (14):8401–8406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kammerer U, von Wolff M, Markert UR. Immunology of human endometrium. Immunobiology. 2004;209 (7):569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mor G, Cardenas I, Abrahams V, Guller S. Inflammation and pregnancy: the role of the immune system at the implantation site. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1221:80–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Burke SD, Barrette VF, Gravel J, et al. Uterine NK cells, spiral artery modification and the regulation of blood pressure during mouse pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63 (6):472–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Plaks V, Birnberg T, Berkutzki T, et al. Uterine DCs are crucial for decidua formation during embryo implantation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118 (12):3954–3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aluvihare VR, Kallikourdis M, Betz AG. Regulatory T cells mediate maternal tolerance to the fetus. Nat Immunol. 2004;5 (3):266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Laskarin G, Kammerer U, Rukavina D, Thomson AW, Fernandez N, Blois SM. Antigen-presenting cells and materno-fetal tolerance: an emerging role for dendritic cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58 (3):255–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rhen T, Cidlowski JA. Estrogens and glucocorticoids have opposing effects on the amount and latent activity of complement proteins in the rat uterus. Biol Reprod. 2006;74 (2):265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roopa BA, Loganath A, Singh K. The effect of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on angiogenic growth factors in the endometrium. Hum Reprod. 2003;18 (9):1809–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Labied S, Galant C, Nisolle M, et al. Differential elevation of matrix metalloproteinase expression in women exposed to levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for a short or prolonged period of time. Hum Reprod. 2009;24 (1):113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lockwood CJ. Mechanisms of normal and abnormal endometrial bleeding. Menopause. 2011;18 (4):408–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bokstrom H, Norstrom A. Effects of mifepristone and progesterone on collagen synthesis in the human uterine cervix. Contraception. 1995;51 (4):249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Westergren-Thorsson G, Norman M, Bjornsson S, et al. Differential expressions of mRNA for proteoglycans, collagens and transforming growth factor-beta in the human cervix during pregnancy and involution. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1406 (2):203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schlembach D, Mackay L, Shi L, Maner WL, Garfield RE, Maul H. Cervical ripening and insufficiency: from biochemical and molecular studies to in vivo clinical examination. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;144 (suppl 1):S70–S76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. da Fonseca EB, Bittar RE, Carvalho MH, Zugaib M. Prophylactic administration of progesterone by vaginal suppository to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women at increased risk: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188 (2):419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Saghafi N, Khadem N, Mohajeri T, Shakeri MT. Efficacy of 17alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate in prevention of preterm delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37 (10):1342–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH, Fetal Medicine Foundation Second Trimester Screening G. Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. N Engl J Med. 2007;357 (5):462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yellon SM, Ebner CA, Elovitz MA. Medroxyprogesterone acetate modulates remodeling, immune cell census, and nerve fibers in the cervix of a mouse model for inflammation-induced preterm birth. Reprod Sci. 2009;16 (3):257–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ekman-Ordeberg G, Stjernholm Y, Wang H, Stygar D, Sahlin L. Endocrine regulation of cervical ripening in humans--potential roles for gonadal steroids and insulin-like growth factor-I. Steroids. 2003;68 (10-13):837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. House M, Tadesse-Telila S, Norwitz ER, Socrate S, Kaplan DL. Inhibitory effect of progesterone on cervical tissue formation in a three-dimensional culture system with human cervical fibroblasts. Biol Reprod. 2014;90 (1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tornblom SA, Patel FA, Bystrom B, et al. 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase and cyclooxygenase 2 messenger ribonucleic acid expression and immunohistochemical localization in human cervical tissue during term and preterm labor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89 (6):2909–2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Farina M, Ribeiro ML, Weissmann C, et al. Biosynthesis and catabolism of prostaglandin F2alpha (PGF2alpha) are controlled by progesterone in the rat uterus during pregnancy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;91 (4-5):211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tilley SL, Coffman TM, Koller BH. Mixed messages: modulation of inflammation and immune responses by prostaglandins and thromboxanes. J Clin Invest. 2001;108 (1):15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kelly RW. Inflammatory mediators and cervical ripening. J Reprod Immunol. 2002;57 (1-2):217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Young A, Thomson AJ, Ledingham M, Jordan F, Greer IA, Norman JE. Immunolocalization of proinflammatory cytokines in myometrium, cervix, and fetal membranes during human parturition at term. Biol Reprod. 2002;66 (2):445–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Osman I, Young A, Ledingham MA, et al. Leukocyte density and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human fetal membranes, decidua, cervix and myometrium before and during labour at term. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9 (1):41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.