Abstract

The Reinforcing Spirals Model (RSM, Citation Withheld) has two primary purposes. First, the RSM provides a general framework for conceptualizing media use as part of a dynamic, endogenous process combining selective exposure and media effects that may be drawn on by theorists concerned with a variety of social processes and effects. Second, the RSM utilizes a systems-theory perspective to describe how patterns of mediated and interpersonal communication contribute to the development and maintenance of social identities and ideology as well as more transient attitudes and related behaviors, and how those outcomes may influence subsequent media use. The RSM suggests contingencies that may lead to homeostasis or encourage certain individuals or groups to extreme polarization of such attitudes. In addition, the RSM proposes social cognitive mechanisms that may be responsible for attitude maintenance and reinforcement. This article discusses empirical progress in testing the model, addresses misconceptions that have arisen, and provides elaborated illustrations of the model. The article also identifies potentially fruitful directions for further conceptual development and empirical testing of the RSM.

The Reinforcing Spirals Model (or RSM, Citation Withheld) seeks to understand media's role in helping create and sustain both durable and more transient attitudes, as well as behaviors associated with those attitudes. By durable attitudes, I refer to values, social identities such as ideology, lifestyle community, and religious conviction, and those attitudes which are closely associated with a given social identity, lifestyle, or ideology. The model also addresses more transient attitudes (e.g., about social policies, other social groups, specific behaviors) that may be associated with identities, lifestyles, and ideologies. The RSM views selective exposure to attitude-consistent content and media effects as two components of a larger dynamic process by which such social identities, attitudes, and behaviors are maintained. The RSM therefore provides a general theoretical framework regarding the role of mediated (and, by logical extension interpersonal) communication experience from which other theorists concerned with various social processes and effects can draw.

The RSM, accordingly, differs in its perspective on understanding the relation of media and attitudes from theories of message influence and persuasion, such as the elaboration likelihood model (Petty, Briñol, & Priester, 2009) and social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2009), which address ways in which particular messages may help form or change attitudes and behavior. The RSM is similar to cultivation theory (Morgan, Shanahan, & Signorielli, 2009) in some respects while differing in crucial ways. Cultivation theory is concerned with the influence of elements of media content, such as a focus on crime and violence, which are relatively uniform and disseminated broadly through society via major media broadcast outlets or distribution channels. In contrast, the RSM is concerned with selection of differentiated media content consistent with and reflecting the values of subgroups within a larger society, be they ideological, religious, or lifestyle-focused. The RSM draws from social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), suggesting that media use in contemporary society is a principal means by which such social and personal identities are maintained. The RSM in some technical respects is similar to the spiral of silence theory (Noelle-Neumann, 1974) with respect to a focus on dynamic, iterative processes, but comes to nearly opposite conclusions regarding the role of contemporary media in the development and sustenance of minority opinions and beliefs. Finally, the RSM combines a systems theory perspective on the role of media in formation and maintenance of attitudes and related behaviors with theorizing about social cognitive mechanisms that can explain the model's proposed dynamics.

In the present article, I will briefly review key tenets of the RSM for readers unfamiliar with the model, and highlight and correct misconceptions regarding RSM that have sometimes emerged, for those with some prior familiarity. I will summarize evidence reported in the literature regarding the RSM and attitude research to date. I will discuss key unanswered questions and further directions regarding the model and the questions it raises regarding the creation and maintenance of attitudes and related behaviors. I also provide figures illustrating the dynamics proposed by the RSM.

Communication patterns and media use as part of a dynamic, endogenous process

A fundamental proposition of the RSM is that media use serves as both an outcome variable and a predictor variable in many social processes. Therefore, it can best be understood in such processes as a mediating or endogenous variable, to use formal statistical modeling language. Less technically, media use is shaped by social context and individual characteristics. Media use may in turn influence many attitudes and related behaviors (Citation Withheld). Media content selection can influence attitudes ranging from beliefs in the appropriateness of aggression to address conflict to religious identification. In turn, individual differences such as dispositional need for arousal and education may influence outcomes such as aggressiveness and religious identification in part through their influence on media content to which people attend.

Another premise of RSM is that the process of media selection and effects of exposure to selected media is dynamic and ongoing. Therefore, the influence of exposure to particular types of media content (determined in large measure by social context, social identity, and prior attitudes), will influence subsequent strength and accessibility of social group identification, attitudes, and behaviors—which in turn will influence subsequent media use, which should continue to reinforce those associated elements of social identity, attitude, and behavior over time. Beliefs about aggressiveness (a formal of personal identity that is also social in its implications) and religious identification, for example, are likely to influence subsequent media content choice.

It should be noted, too, that while my focus has been on media content choice, choice of interpersonal communication activities, involvement with organizations, and other non-mediated communication activities are equally relevant to such processes. Indeed, in the era of social media, the distinction between mediated and interpersonal communication selection and use is increasingly becoming elided.

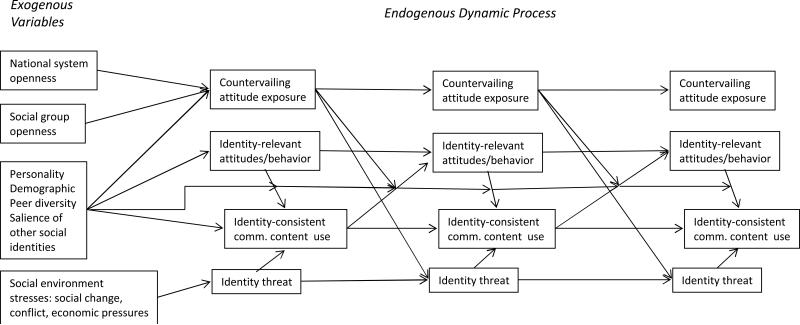

Why spirals typically reinforce and maintain attitudes, rather than driving attitudes towards extremes

I had illustrated this process in its simplest form as a process in which one can see predictive paths from media content exposure to attitudes and behaviors, and from attitudes to media content exposure, at any time point (Citation Withheld). In retrospect, providing such a simplified illustration may have been a mistake, as I have seen authors arguing that RSM is tested by predicting continuing and even non-linear growth over time in a given type of media use and outcome. However, in the same paper I also pointed out that such a process if unchecked would lead to a positive feedback loop in which effects grow out of control, to use systems theory (e.g., von Bertalanffy, 1968) language. In other words, there may be a tendency to positive feedback and growth in media use and endorsement of associated attitudes for limited times (e.g., during processes of socialization) but at some point the positive feedback loop normally has to stop. Even during times of socialization, tendencies toward positive feedback loop-type effects are most likely only for those particularly at risk due to social circumstances or personality-based vulnerabilities (Citation Withheld), and even then normally would be limited by concern about consequences and other externalities. A true positive feedback loop would lead to extremes of media use, attitudes, and behavior that one sees only in highly atypical cases such as fundamentalists and zealots of various stripes; terrorists of course come to mind. The operative questions, then, as described in Citation Withheld and discussed later in this article, concern the contingencies that determine when effects tend to increase and when effects will tend toward homeostasis. I have therefore provided an illustration of the model that more clearly indicates its contingent nature (Figure 1) and provide additional discussion of possible moderators later in the article.

Figure 1.

A version of the Reinforcing Spirals Model including contingent factors normally leading to homeostasis and maintenance of identity-relevant attitudes and those escalating the process. All relationships are positive except the dampening effects of system openness and of competing social identities on the spiral process, shown as interaction effects. Cross-sectional correlations not illustrated.

Reinforcement and maintenance of identity-central attitudes—towards homeostasis

The RSM therefore is concerned both with identifying those unusual contexts in which such feedback loops may range out of control, and with understanding the normal process, in which homeostasis is reached (Citation Withheld). The reinforcement/maintenance of media content selection and effects may be considered a homeostatic process or negative feedback loop (i.e., operating much as a thermostat does). The RSM argues that when social identity is under threat (during political campaigns or other times when rival ideologies are becoming salient, or at times of economic or social strain), selective use of attitude- and identity-consistent content should increase until a satisfactory equilibrium is reached. When identity threats are diminished, such selectivity can be reduced.

By homeostasis I refer to a balance in which identity-relevant attitudes (e.g., ideology, religion, or lifestyle) are adequately maintained in the face of competing worldviews. Exposures to competing worldviews come through mediated and interpersonal experiences. It is psychologically more comfortable for most individuals to select interpersonal and mediated experiences that reinforce social identity (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). On the other hand, it is functional and enjoyable, in living in a complex society, to have wide exposure to information that is likely to have utility (e.g., Knobloch, Dillman Carpentier, & Zillmann, 2003) or offer pleasure and a way to manage and adjust moods and explore personal meaning (Knobloch, 2003; Oliver & Raney, 2011; Zillmann, 1988), which are likely to result in exposure to attitudes about the world inconsistent with one's own. Therefore, selectivity of attitude- and identity-consistent content are likely to operate only to the extent necessary to maintain a reasonable level of comfort with respect to protecting identity-central attitudes and beliefs.

Reinforcement of attitudes as a theoretically and socially important phenomenon

In a sense, then, the RSM revisits classic work by Klapper (1960) and Berelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee (1954), which argued media tended more to reinforce existing beliefs than to change them. The RSM points out that if one is concerned with understanding media's relevance to identity-relevant attitudes such as values and ideology, the reinforcement argument is a sensible one. Moreover, while these reinforcement arguments are typically described in texts as theories of limited media effects (e.g., Baran & Davis, 2012), such socialization and reinforcement effects are of fundamental social importance (see Stroud, 2010, for a similar point). How identity-relevant attitudes are formed through socialization (of which media are a part) and then maintained in a complex, diverse society is a central question for social science. If media's role is to help initially form and then help reinforce those attitudes so that they survive in the face of myriad alternative points of view, it is a significant role indeed. Moreover, media exposure within a reinforcement perspective can influence behavior by strengthening the attitude-behavior relationship through increased attitude accessibility (Fazio, Powell, & Williams, 1989), as well as by modeling how to enact behaviors successfully (Bandura, 2009).

The RSM and a sum-over-indirect-and-direct–effects approach to assessing media effects

The RSM can be viewed in two ways. On one hand, the RSM seeks to theorize the role of media use in the development and maintenance of social identities and related attitudes. On the other, it is a broader conceptual framework that emphasizes the mediating role of mediated and interpersonal communication in social processes and associated effects. This framework can readily be drawn upon by theorists interested in understanding specific social processes and communication effects. The specific proposed pathways and relationships illustrated in Figure 1 are likely to evolve with increased empirical scrutiny and theoretical thinking, or perhaps in time be superseded. However, I believe such future approaches will draw on the basic insights offered with respect to the emphasis on mediated and interpersonal communication content choices as an endogenous factor in dynamic social processes.

The RSM perspective arguing for the mediating role of communication processes also suggests alternative and perhaps more powerful ways of assessing the impact of media exposure on attitudes and behavior. Traditional media effects analyses attempt to assess cause-effect relations by controlling away as many other variables as might be implicated in the causal process, to minimize the threat of third-variable, alternative causal explanations. The RSM, in contrast, would suggest that further insight can be gained by incorporating variables such as individual differences and social influences as predictors of media use rather than as statistical controls. One can then consider the total effect of media use as summed across all the direct and indirect effects. In other words, RSM suggests that traditional media effects analyses, by trying to control for variables that are part of the causal process and are not really third variables providing competing causal explanations, in fact are likely to reduce the actual effects that should be attributed to the role of media use (see Citation Withheld, for an example).

Reinforcing spirals and extreme attitudes

While the RSM is primarily concerned with explaining the maintenance and reinforcement of attitudes relevant to social or personal identity, it is also concerned with the contingencies under which these attitudes, instead of reaching homeostasis, move towards extremes. There clearly are circumstances in which perceived threat to identity is very strong (perceived threat to the integrity or survival of the group), identification with that group is strong and relatively unaffected by competing social identifications with rival claims (e.g., role as parent), or social group norms carefully minimize exposure to countervailing perspectives or national cultures control exposure to such perspectives effectively. In such circumstances (when the system is relatively closed rather than relatively open, to use systems theory language), the homeostatic influences begin to break down and the possibility of positive feedback loops and extreme outcomes arises (see Citation Withheld, for a more detailed discussion).

Social cognitive mechanisms by which reinforcement processes may take place

Another aspect of the RSM is its proposal of social cognitive mechanisms that may help explain how both durable and more transient attitudes may be reinforced by media content exposure choice. Principal among these is attitude and construct accessibility. Fazio and colleagues point out that attitudes that are central to our personal or social identity are normally chronically accessible: they are so often accessed that they come very readily to mind (Fazio et al., 1989). Chronic accessibility, then, results from frequent and ongoing activation of attitudes. The RSM argues that a major source for such frequent and ongoing activation is the selective choice of attitude- and identity-consistent communication experiences (e.g., conversation partners and media content, and, in the era of social media, both at once).

The role of identity and attitude accessibility

Therefore, attitudes such as values, ideology, and religion, and in particular the accessibility of social identities themselves, should influence media content choices and in turn such choices should continue to support the accessibility of those central attitudes. In fact, the RSM made the prediction that selective exposure to attitude-consistent content should in turn have an immediate, short-term effect of increasing accessibility of those identities and identity-relevant attitudes Citation Withheld). This was a risky prediction, as chronically accessible attitudes such as elements of one's social identity are quite stable and should not be readily influenced by brief message exposures. However, it seemed that an effect on accessibility immediately following exposure was a reasonable possibility consistent with the reinforcement hypothesis and the proposed mechanism of reinforcing chronic accessibility with each exposure. Comello (2013) develops this argument, proposing that social and personal identities themselves, consistent with the active-self perspective of Wheeler, DeMaree, and Petty (2007), are influenced in terms of accessibility as a function of media exposure, as well as moderating the impact of such exposure. The RSM (see proposition 6, Citation Withheld) also predicted that the influence of attitudes associated with a given identity would be strengthened briefly following such exposure, as a result of increased accessibility of that identity.

Empirical Evidence Regarding the Reinforcing Spirals Model: A Summary, Update, and Review of Unanswered Questions

To understand the RSM and to place unresolved issues into context, it is useful first to review the evolution of the model across a series of initial studies through which it developed. These included a first examination of ways media use could influence attitudes, and in turn ways attitudes could influence media use, in longitudinal data (the “downward spiral model”). Other work examined how dispositional and situational variables could dampen or accentuate spiral effects. Another study conceptualized media use as a mediator not just of prior effects of use, but of a wide range of individual difference variables that typically have been instead modeled as statistical controls, not implicated in the causal process.

Initial Evidence: Socialization and Longitudinal Data

Work on the RSM was launched with a longitudinal study of exposure to violent media content in movies, video games, and on the internet, and its effect on aggressive attitudes. The study employed a four-wave data set including 2,550 youth mostly aged 12-14, collected in 16 communities around the U.S. This age range is a key time of identity formation and socialization (Adams & Marshall, 1996). As such, it was an appropriate place to test a simplified model in which aggressiveness influenced media use, and media use influenced behavior, over time. Over this limited timeframe, tendencies to increases in both media use and behavior were plausible.

Downward spiral model

The study in fact found that exposure to the violent media content indeed prospectively predicted aggressiveness (defined and measured attitudinally) among these younger adolescents and aggressiveness prospectively predicted violent content media use after inclusion of controls. A second analysis tested a more stringent model, in which we tested as predictors only the extent to which violent media exposure or aggressiveness varied at each wave from the respondents’ age-adjusted mean. In so doing, we were looking at only within-person variation, thus eliminating possible confounding due to between-person differences (i.e., controlling individual difference variation). Similar results were found, except that for the aggressiveness to violent media content exposure relation, the effect was significant modeled concurrently but not prospectively (Citation Withheld). In that paper, we described the findings as a “downward spiral model,” in which media effects of violent media content exposure and aggression could be expected to feed on one another. (It should also be noted that Eveland, Shah, & Kwak, 2003, had tested a similar process using the same name in the context of political knowledge and information processing, using a two-wave data set.)

Moderation of spiral effects by dispositional and situational variables

However, considering our findings in retrospect, it seemed to us that we had described the phenomenon with perhaps too-broad a brush stroke. Perhaps the small but statistically significant effects we had found masked something perhaps more interesting: little or no effect of violent media content use on most youth, but relatively larger effects on youth who might be particularly vulnerable to the impact of violent media content exposure.

We revisited the same data set employing a different analytic model. This time, we proposed that dispositional factors such as sensation-seeking (the enjoyment of arousal and risk-taking; Zuckerman, 1994), and situational factors such as problems in school or with bullying would tend to magnify the violent media content-aggressiveness relation. In other words, the kinds of variables we typically used as controls could be incorporated into the causal model as moderators. We suggested this interaction would occur both when these situational and dispositional factors were relatively high or low as a matter of individual difference, or because they were particularly high or low relative to a youth's age-adjusted mean (e.g., at a given wave he or she was being bullied more than usual or less than usual), and found support for our predictions (Citation Withheld). These findings also helped lay the foundation for the RSM proposition that the relation between exposure and effects on attitudes would tend toward homeostasis except in the presence of contingent conditions such as identity threat that increased vulnerability to communication influences (see Citation Withheld, for details regarding these contingent conditions). Current thinking regarding key contingencies (notably identity threat, norms of group and national information openness, and exposure to countervailing attitudes) is summarized later in this article and illustrated in Figure 1.

Media use as a mediating variable

These contingent results led to further thinking about the nature of the media exposure and effects causal process. In the Citation Withheld paper, variables that typically were used as controls were instead conceptualized as moderators of the causal process. Once one begins to think of such variables as part of the model instead of as controls, it was a natural step to model them as predictors of media use and thus model media use as an intervening process using mediation analyses. Media use choice clearly is a function of many determinants, as authorities on selective exposure (e.g., Zillmann & Bryant, 1985) and uses and gratifications (e.g., Rubin, 2009) suggest. Therefore, variables such as sensation-seeking or peer acceptance should not only be moderators of exposure choices and consequent effects, but also exist within the larger causal process. We tested this using a cross-sectional U.S. national probability sample survey of the U.S. population (N = 1272) and found that exposure and attention to entertainment and news media content regarding crime and accidents explained a significant amount of the relation of various individual-difference variables on perceptions of alcohol-related risks. For example, exposure and attention to such entertainment and news content explained approximately 50% of the effects of gender and of sensation-seeking, and about 25% of the effects of education and of negative personal experiences, on concern about alcohol-related risks (Citation Withheld).

Evidence from Subsequent Studies and Directions for Future Research

The Reinforcing Spirals Model, then, develops the idea of media content exposure being both cause and effect of various attitudes about oneself and about the social world. It develops the theoretical inferences that can be drawn from that original premise, as one integrates that perspective into larger questions of social identity and social context, and proposes causal models that capture some of the dynamic complexities inherent in the role of media in social experience. Many of these ideas and inferences are challenging to test, given the time-dynamic aspects of the model and concern with social context issues that are not easy to capture in a data set. However, a number of studies have made further noteworthy progress in this regard. Here, I will review studies examining the RSM in the context of youth socialization and behavior, studies examining spiral issues with respect to political issues and political contexts, and studies that have assessed the social-cognitive mechanisms proposed to explain RSM effects. I will also discuss in each area key unanswered questions and directions for future exploration.

Further evidence regarding reinforcement processes in socialization

Socialization, particularly during adolescence and young adulthood, can be expected to be a particularly fruitful context for exploring RSM claims. As noted earlier, since personal and social identities are still in formation, there is more room for escalation of both identity-consistent exposure and effects. The reinforcing spirals process during socialization can help crystallize personal and social identity as well as maintain such identities over time.

Bleakley, Hennessy, Fishbein, and Jordan (2008) conducted a two-wave panel survey of 501 Philadelphia adolescents examining the relationship between exposure to sexual media content and sexual behavior. Using extensive controls and two-stage least squares analytic procedures utilizing instrumental variables, which facilitate testing of directional hypotheses within a single wave, they found evidence for prediction of behavior by exposure and exposure by behavior within wave. Comparable prospective relationships were only found for behavior and exposure overall, not for change in behavior or exposure over time. The authors attributed this to the degree of stability of these outcomes over the one-year period, as prior behavior explained over 70% of variance in subsequent sexual activity and prior exposure to sexual media content explained over 80% of variance in subsequent exposure. The authors also note that the path from sexual activity to media exposure was stronger than the path from exposure to behavior effects concurrently, but the opposite was true longitudinally.

Peter and Valkenburg (2009) conducted a three-wave survey among 962 Dutch adolescents regarding the impact of sexually explicit internet content in particular on perceptions of women as sex objects. Peter and Valkenburg found, as suggested by the RSM, that structural equation model tests supported representing sexually explicit internet content as both prospectively predicting perceptions of women as sex objects and as prospectively predicted by perceptions of women as sex objects. However, when the models were compared for male and female adolescents, attitudes suggesting women were sex objects predicted use of sexually explicit internet content only for males. In other words, the RSM predictions were supported for adolescent males, but not for females, in the context of sexually explicit internet content.

A two-wave study of violent video game use and aggressive behavior among elementary school children in Germany (von Salisch, Vogelgesang, Kristen, & Oppl, 2011) using cross-lagged structural equation models found that children's aggressiveness predicted subsequent violent media use but the reverse was not true. The authors attributed the lack of effect of video game exposure on the high stability of aggressive behavior and the relative constraints on such behavior among these younger children, when disposition and family environment heavily determine such behaviors. The authors make the interesting suggestion that socialization processes regarding aggression such as reinforcing spirals may begin in the later elementary school years, as more aggressive children establish patterns of media use that will help sustain those patterns as they move into adolescence.

RSM claims were assessed in the context of interpersonal conversation instead of media exposure in the context of body image among college students (Arroyo & Harwood, 2012). The authors found, in a two-wave study, that conversations about being overweight decreased body satisfaction, and conversely body dissatisfaction led to such conversations, tending to reinforce self-perceptions regarding body image problems.

Knobloch-Westerwick and Hoplamazian (2012) investigated selective exposure effects on reinforcing gender role and gender conformity. Gender conformity (traditional masculine and feminine identification) was assessed pre- and post-test among 253 undergraduates. Both biological sex and pretest gender conformity predicted selective exposure to gender-typed magazines. Such exposure also mediated effects of sex and pretest gender conformity on various aspects of posttest gender self-concept, consistent with the RSM proposition.

Citation Withheld and Citation Withheld address the role of music television such as MTV in adolescent cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana uptake. The authors argued, per the RSM, that exposure to music television (in which substance use is often shown as normative) would provide initial socialization into such norms. Such vicarious socialization would lead to substance use uptake, mediated by involvement with substance-using peers. This prediction was supported in both cases.

The relationship of substance use increase to the trajectory of music use was complex and provided some telling insights into the dynamics of selective media content choice. First, use of music television did not increase along with increased substance use. There was a good substantive reason for the two behaviors not increasing in tandem. Socialization into substance-using peer groups typically involves a move to music genres specific to those peer groups (van der Rijt, d'Haenens, Jansen, & de Vos, 2000). Music television presented a broad range of popular music, not focused exclusively on whatever the specific genres preferred by substance-using peer groups. Therefore, one might expect increases in use of specific music genres rather than music television as youth socialized into substance use, or at least increased use of media through which one can gain access to more specific musical genres. Such media include radio and, in more recent years, music downloads and streaming music websites. These data sets unfortunately did not have data on use of more specific music genres to permit assess this to be tested directly. However, other analyses of one of these data sets (Scheier & Grenard, 2010) demonstrated that increasing substance use over time was associated with increasing radio listenership. As these data were collected before music downloading was widespread, the easiest way at the time to access peer-group specific music genres was via radio. In other words, as substance use increased youth increased their radio listenership, which permits access to the musical content preferred by their substance-using peer group.

Research questions and challenges regarding youth, socialization, and reinforcing spirals

Two key issues regarding specification of the RSM are raised by these more recent studies. One involves conceptualizing selective exposure to identity-consistent content in terms of quantity versus specificity or extremity. The second involves the likelihood of asymmetry of lags between media use and attitudes in the spiral process.

Escalation of identity-consistent media use—specificity, extremity, quantity

The music television studies (Citations Withheld) highlights an issue that was undeveloped in the original discussion of the reinforcing spirals model—namely, the nature of escalation in media use associated with a given social identity during the process of socialization or during identity threat. Originally, this escalation was conceptualized primarily as a greater amount of identity-consistent media use. However, another form of increased selectivity associated with and reinforcing a social identity is moving to content that is more clearly identified with the social identity.

In the case of youth and substance use, the move to more identity-relevant content over time may involve listening increasingly to specific genres of music favored by a group of substance-using peers (Mulder, Ter Bogt, Raaijmakers, Vollebergh, 2007; van der Rijt et al., 2000). In the case of females perceiving women as sex objects (Peter & Valkenburg, 2009), it might be that such identification leads them to select fashion and body-image content, rather than sexual content, on the internet. In the case of political socialization of youth, it may involve selection of more radical or extreme political news and commentary, not necessarily more time on such news and commentary overall.

It seems clear that understanding media influences on socialization and social identity requires close examination of specifics of media content, attention to types of content, and media outlets used, to properly operationalize identity-consistent media context use. Measures of media use that are too generic to capture shifts to more extreme or more social identity-specific content probably will not accurately characterize the role of media in socialization.

Asymmetry of lags between media use and attitudes

The Bleakley et al. (2008) study, along with older results (Citation Withheld) suggest that attitude/behavior to exposure effects are particularly strong concurrently. Modeling this relationship concurrently or using short lags makes a good deal of logical sense. Selective choice of media content is influenced by the attitudes salient at the moment of choice (e.g., Knobloch-Westerwick, 2012). Findings of prospective influence of attitudes on exposure after lengthy lags (e.g., six months or a year) are perhaps simply approximating the effects of more proximal attitudes on selection choice, since these attitudes are typically fairly stable (see Eveland & Morey, 2011, regarding lag duration issues).

Further evidence regarding reinforcement processes in politics and ideology

As noted earlier, Eveland et al. (2003) suggested the presence of upward and downward spiral effects in political knowledge and media use paralleling the RSM perspective. Since that time, a number of studies concerned with political communication and public policy have returned to these issues. These include studies in science and environmental communication, political campaign contexts, and in contexts of ongoing political conflict, particularly in the Middle East where political and social identity are central.

Reinforcing spirals in environmental and science communication

Work on reinforcing spirals processes in environmental and science communication is still in its beginning stages. Eveland and Cooper (2013), in their integrated model of communication influence on beliefs, note the likelihood of reinforcing spiral processes in which beliefs selectively influence media use that is likely to in turn influence or reinforce science beliefs. Zhao (2009) found evidence for reciprocal relations consistent with the RSM between selectivity of attitude-consistent content and climate change beliefs in cross-sectional data.

Political campaigns and spiral processes

Stroud (2010) analyzed the relationship between ideology and partisanship of media use on political polarization. She analyzed cross-sectional and two-wave panel surveys around the 2004 U.S. elections, and tested for interactions between ideology and partisan media use on polarization. These predictions were generally supported. In addition, the same analyses suggested that greater polarization predicted greater use of partisan media, a bidirectional pattern consistent with the RSM. Time-series analyses provided further support for the media exposure to polarization effect but not for polarization to media exposure, so in the time series analyses support for RSM predictions were mixed.

Schemer (2012) provides a test of the RSM in the context of a Swiss referendum on restricting a controversial law regarding granting of political asylum, employing a three-wave panel survey. Hypotheses that attention to political ads (heavily opposing asylum policies) would prospectively increase negative feelings about asylum seekers, and conversely negative feelings about asylum seekers would prospectively increase attention to political ads, were supported across each of the two lags. The cumulative result was, as expected, greater negative feeling about asylum seekers by the end of the campaign.

Schemer also examines whether the effects intensify or are relatively uniform across each lag. Results suggest that the effects are uniform. In other words, while there may be cumulative effects, the process is not a non-linear one. Per the systems theory language employed earlier, people satisfice in terms of the amount of information sought and the intensity of emotion felt.

Finally, Schemer also tests the relative strength of the two paths, finding they are comparable in the first lag but the attention to affect lag appears stronger in the second. Combined with the Stroud (2010) findings, these results suggest that in the particular context of a political campaign, reinforcing spiral processes may influence exposure and attention, but that as the campaign moves forward, as one might expect, selective choice of attitude- and identity-consistent content becomes less a factor, perhaps due to ceiling effects relative to available time and attention and burnout relative to attending to campaign messages.

Politics, identity, and spiral processes in the Middle East

The RSM perspective may have particular utility for thinking about media and political conflicts in the Middle East, entangled as they are with issues of political, religious, national, and regional identity. For example, Nisbet and Myers (2010) examine how media use choice (use of transnational TV) may lead to predominance of transnational Arab or Muslim identity over national identities. They examined cross-sectional representative survey data collected over four years from six countries in the Middle East, and found that indeed transnational TV viewing was associated with stronger Arab and Muslim political identification relative to national identification. Moreover, this effect was moderated by education. Generally, the more educated a respondent was, the weaker was Muslim identification relative to national identification. However, this gap closed with greater transnational TV viewing. Effects of internet viewing moderated effects in the opposite way. Generally, internet access was negatively associated with Muslim versus national identification, and this became stronger as education increased.

These cross-sectional findings of course do not test longitudinal predictions of the RSM, but they are consistent with the premise that social identity is formed in part as a result of exposure to identity-consistent content. The Nisbet and Myers (2010) results also underscore the potential moderation of such effects by individual differences such as education.

A recent study combines adolescent socialization and political conflict issues, examining the impact of repeated and cumulative exposure to political violence in the media on aggressive behavior and post-traumatic stress symptoms in Palestinian and Israeli youth (Dvir-Gvirsman et al., in press). Using longitudinal data (N = 1207), the authors found that the effect of mediated exposure after controlling for other exposures to violence predicted these negative outcomes, and that the effect from aggressiveness and stress symptomology to selective exposure to violent media content was also present though the weaker of the two relationships. This pattern is consistent with RSM predictions; the smaller prospective path between aggressiveness and stress to selective exposure is consistent with other findings discussed above.

Research questions and challenges regarding politics and ideology and the RSM

Several conceptual and operational issues merit further attention and empirical development within the RSM. These include spiral effects in the context of political campaigns, specificity of media content used, conceptualization and operationalization of identity threat and exposure to countervailing attitudes/system openness, and study of systematic national and group norms regarding openness to heterogeneous perspectives.

RSM and political campaigns

Political campaigns are a distinctive information environment. Findings from Stroud (2010) and Schemer (2012) suggest the potential for mutually reinforcing effects between exposure and attitudes at least earlier in the campaign process, but a predominance of media use to attitude effects as the campaign moves forward. Explicit testing of such a hypothesis would be valuable. It would also be interesting to see if stronger exposure/attitude/exposure effects, and greater polarization, might be found in some subgroups, e.g., those under greater identity threat or for whom ideological identity is relatively dominant over other social identities and roles.

Specificity of identity-consistent media content used

Above, I mentioned the issue of specificity in operationalizing identity-consistent media content use. Namely, time spent and amount of media consumed may not change, but a switch towards more extreme outlets expressive of more extreme viewpoints would suggest escalation or polarization of social identity. Therefore, operationalization of identity-consistent media content use ideally would distinguish content in terms of intensity or extremity, and weight use accordingly. Comparable questions arise regarding the nature and type of interpersonal conversation and conversation partners, whether face-to-face or via internet or social media.

Conceptualizing and operationalizing identity threat

Conceptualizing and testing the role of identity threat also needs work. Identity threat may actually be shorthand for a family of variables, which may or may not operate in the same way. For example, identity threat may come from social forces accumulating over time. One example would be economic change leading to reduced employment opportunity and the loss of the identity associated with such reduced opportunity. Another might be immigration: increased diversity is a threat for the indigenous population, and assimilation poses threats to existing social identity among the immigrant population. A third might be changes in social and moral values, so that the norms of one's referent group may no longer appear reflected in social norms, laws, and media expression. A fourth might involve international conflict, or internal strife and breakdown of social and legal order. A fifth, of course, is developmental: adolescence is typically a time of identity shifts.

Challenges in investigating effects of national and group openness

The difficulties in carrying out research on differences in national and group openness to heterogeneous perspectives, especially in more extreme contexts, should be apparent. Groups and people under intense identity threat are likely to be mistrustful, and access difficult to obtain when the system is relatively closed. Testing the model in closed societies, or among relatively closed social groups, is inherently difficult—it is likely to be hard to get access and cooperation, and those who cooperate are not likely to participate in the more extreme, more closed groups. Such research might require approaches such as web tracking and unobtrusive measurement. However, as noted, it is possible for ambitious and skilled research teams to collect data in challenging environments exploring these issues (e.g., Dvir-Gvirsman et al., in press).

Conceptualizing and testing exposure to countervailing attitudes

By the same token, work is needed on conceptualizing and testing the role of exposure to countervailing attitudes. On one hand, exposure to such attitudes is essential to the existence of an open system, and works against spirals turning into positive feedback loops resulting in extreme outcomes. As illustrated below in Figure 1, this variable is hypothesized to be a consequence of system openness, resulting in increased exposure to diverse perspectives as experienced by the individual respondent in their communication environment. Not all exposure to communication is selective; much information is simply encountered in the course of every day life. Moreover, reinforcing existing attitudes and social identity are not the only reasons for selectivity in media use. Media content sought for reasons of utility, pleasure, or other emotional needs (Knobloch et al., 2003; Zillmann, 1998) may lead to exposure to countervailing attitudes, as might strategic interest in opposing viewpoints by the politically involved (Citation withheld). The more open the system and social group, the more likely such exposures are.

However, some specific countervailing attitude exposures may escalate into identity threats. In such cases, the RSM would suggest that use of identity-consistent communication content should increase (via increased frequency of use, intensity of attention, or extremity of content selected), to maintain social identity homeostasis (see Figure 1). For example, public debate about an issue that is relevant to a social identity but not central to it (e.g., a proposed tax on cigarettes may be seen as an example of government interference and excessive taxation by political conservatives in the U.S., but in itself is may be less noxious than other possible initiatives) is not likely to trigger identity threat. In more extreme examples, when more fundamental beliefs or values are on the line, such as abortion or gun control, exposure to countervailing attitudes is likely to generate identity threat and stimulate greater selective use of identity-consistent communication content. Moreover, when public debate and countervailing attitudes are successfully framed as a threat to core values and beliefs, to that extent countervailing exposure becomes identity threat. In the U.S., the portrayal of the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) as fundamentally intrusive into individual liberties, and the widespread circulation of rumors such as requirements to imbed identifying computer chips into everyone's flesh (e.g., McGuire, 2012), may exemplify the move of public debate from reasoned discussion of conflicting attitudes and beliefs to identity threat and polarization, associated with escalating reinforcing spiral effects.

Another question regards when internet use serves as venue for greater openness and access to other, countervailing attitudes and perspectives that might dampen extreme political and social identities (e.g., Nisbet & Myers, 2010), and when it may serve to support polarized and extreme perspectives, as suggested by Sunstein (2001). Clearly, the extraordinary range of content available via the internet can serve to increase exposure to diverse viewpoints or permit near-exclusive focus on viewpoints from a single identity community. One set of questions for future research involve identification of the moderating factors that lead to more extreme social identification and positive feedback processes, versus those that lead to homeostasis.

Moderating effects of relative social identity salience and other individual differences

Another issue raised in the earlier discussion of the RSM regards a host of limiting factors in the lives of any given individual. Each of us has multiple social and personal identities (Comello, 2009; Wheeler et al., 2007). A person may be a staunch conservative, evangelical, and also an impassioned angler and golfer, a mother, a community volunteer, and a teacher. Time and attention is a finite resource. After a certain point, attention to issues and media content associated with one social identity comes at the cost of devoting resources to other roles and interests. Perhaps the single strongest and most compelling reason that spirals reach homeostasis is simply that people satisfice. When media use (including interpersonal exchange via internet and social media) is in balance with identity threat, there is no need to increase use. Identity-specific media use (and interpersonal conversation) and effects may increase when threat increases, but diminish as threats become less salient and other identities and interests compete for time. The dampening effect of competing social identities, and other individual differences that impact how media and interpersonal communication sources are used and their subsequent effects (e.g., Citation Withheld; Valkenburg & Peter, 2013; see effects of education on media use-identity relations in Nisbet & Myers, 2010), are illustrated in Figure 1. There is considerable scope for future research to examine the impact of the salience of the particular identity under threat relative to a person's other social identities.

Also worth exploring are other potential moderators, including extent of peer diversity or homogeneity or demographic factors such as education, that might influence willingness to accept complexity and assimilate opposing views. Personality factors such as sensation-seeking may also play a moderating role. For example, sensation-seeking would predict a preference for increased arousal, and the anger and indignation likely to arise when consuming more extreme ideologically-consistent media content may provide such arousal.

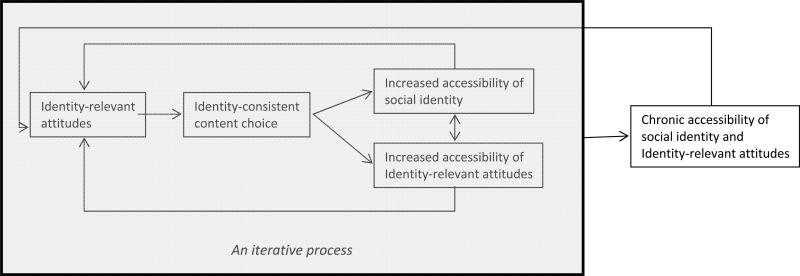

Evidence regarding social cognitive mechanisms

As discussed earlier, the RSM (Citation Withheld) predicted that exposure to identity-consistent content would be predicted by ideology or other identity markers, and that as a result of that selective exposure the social group identity would become more accessible in memory and attitudes associated with that social group identity would also become more accessible in memory (see Figure 2). More accessible constructs and attitudes are significant because they are more likely to influence judgment and behavior than constructs and attitudes that are less accessible (e.g., Fazio et al., 1989).

Figure 2.

A social-cognitive mechanism supporting the reinforcing spirals process.

Knobloch-Westerwick and Meng (2011) collected pretest data on attitude and political self-concept accessibility on 157 undergraduates. In a session approximately four weeks later, the participants were given an opportunity to select identity-consistent or inconsistent online news magazine stories, followed by an assessment of the accessibility of political identity. As predicted by the RSM, participants tended to select and attend more to the identity-consistent content, which in turn was predictive of increased accessibility of the relevant political ideology.

A second study provided a test of the second part of the RSM prediction (Citation Withheld) that selective exposure to identity-consistent content influenced by social identity would also increase the accessibility of attitudes associated with that identity (Knobloch-Westerwick, 2012). Knobloch-Westerwick conducted a study online shortly prior to the 2008 U.S. presidential election. In a first data collection session, general population adult participants (N = 205) provided data regarding attitude accessibility and political identity as assessed using partisanship measures. In a second session, participants browsed articles online with either identity-consistent or inconsistent content. Selective exposure to identity-consistent media content increased accessibility of identity-consistent political attitudes, consistent with RSM predictions. Moreover, accessibility of partisanship was influenced indirectly via attitude accessibility.

Future research opportunities regarding social cognitive mechanisms proposed by the RSM

The studies by Knobloch-Westerwick and colleagues provide strong evidence regarding the social cognitive mechanisms proposed by the RSM. Future research regarding contingent conditions would advance understanding of these mechanisms and provide more rigorous tests of other claims of the RSM. For example, experimental manipulations that successfully heightened identity threat should strengthen the effects found in the above studies. Effects might also be stronger for persons for whom the identity in question is relatively salient, compared to other social roles and identities. Another opportunity, though perhaps more challenging given the difficulty of finding an appropriate manipulation, would be to increase or decrease openness to experiencing identity-inconsistent points of view, perhaps by highlighting social group norms regarding such openness. Increased openness should attenuate effects of selectivity of attitude- and identity-consistent content and thus reduce impact on identity and attitude accessibility.

Concluding Remarks

This review and update serves primarily to re-emphasize that the RSM describes processes leading to the formation (during socialization processes) and subsequent maintenance of attitudes, including identity-relevant attitudes such as ideology and religiosity, as well as associated more transient attitudes and behaviors. The model seeks to describe the role of selective exposure and media influence in the socialization process. In this article, I strive to clarify how selective identity-consistent media content use can help sustain attitudes in the face of identity threat, and how system openness helps maintain homeostasis and reduce the possibility of positive feedback loops and extreme outcomes. The model also addresses individual differences in identity salience, demographics, and disposition that might also moderate the iterative exposure-impact process, and underscores the contingent predictions of the model. This presentation of the RSM provides a more elaborated visual representation of both the model and the social cognitive mechanisms posited to help explain RSM phenomena.

Several elements, however, are new, relative to the previous (Citation Withheld) discussion of RSM. The earlier version focused on exposure frequency or intensity of attention to identity-consistent media content. This version explicitly acknowledges that some media content is more strongly associated with certain identities (substance user, political extremist) than others. In other words, someone who is becoming increasingly conservative politically may not increase overall exposure to conservative information sources, but may move from use of more moderately conservative to more extreme talk shows, blogs, and internet sites.

Another shift is acknowledging evidence suggesting that attitude to exposure lags may often be shorter than exposure to attitude lags (e.g., Bleakley et al., 2008; Citation Withheld). After all, if there is an attitudinal impact, it is easy to enact shifts of exposure choice immediately. This, of course, poses challenges to modeling RSM phenomena. When both lags are relatively short, there may be little problem. However, in panel studies with longer lags, it may prove more appropriate to model the attitude to exposure relationship as concurrent, especially in contexts focused on reinforcement and identity threat rather than socialization.

In addition, I have sought to clarify the dual purpose of the RSM. On one hand, it is an effort to theorize the role of media use in development and maintenance of identity-relevant attitudes. On the other, the RSM is a conceptual framework proposing using media use as a mediating variable in understanding social processes and effects rather than as an independent variable. The specific ways in which this is done across social processes and outcomes of course may be quite distinctive. In this sense RSM is a conceptual framework from which other theorists can draw in creating context-specific theories.

Possibilities for future research have also been clarified, based on the growing research literature relevant to RSM processes. The contingent role of identity threat, exposure to countervailing attitudes, and communication openness have been more clearly specified, and remaining difficulties in studying these constructs discussed. The potential for exploring identity threat and its impact on exposure choice, in both lab and field settings, is highlighted.

It remains my hope that continued exploration of ideas suggested by the RSM may lead to greater understanding of the role of media and other communicative processes in socialization and maintenance of attitudes. In a larger sense, I hope the model stimulates more theoretical and empirical work acknowledging the complex, dynamic, and endogenous roles of media and other communicative experience within a complex and changing social environment.

Acknowledgements

Research on which this paper is in part based was supported by grants AA10377 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and DA12360 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The viewpoints herein are the author's and do not necessarily represent those of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Author note: The author is Social and Behavioral Science Distinguished Professor at the School of Communication, The Ohio State University, 3022 Derby Hall, Columbus, OH 43210, slater.59@osu.edu

References

- Adams GR, Marshall SK. A developmental social psychology of identity: Understanding the person-in-context. Journal of Adolescence. 1996;19(5):429–442. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo A, Harwood J. Exploring the causes and consequences of engaging in fat talk. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2012;40(2):167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communications. In: Bryant J, Oliver MB, editors. Media effects: Advances in theory and research. 3rd ed. Routledge; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 94–124. [Google Scholar]

- Baran SJ, Davis DK. Mass communication theory: Foundations, ferment, future. 6th ed. Wadsworth; Boston, MA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson B, Lazarsfeld PF, McPhee WN. Voting: A study of opinion formation in a presidential campaign. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Hennessy M, Fishbein M, Jordan A. It works both ways: The relationship between exposure to sexual content in the media and adolescent sexual behavior. Media Psychology. 2008;11(4):443–461. doi: 10.1080/15213260802491986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comello MLG. William James on “possible selves”: Implications for studying identity in communication contexts. Communication Theory. 2009;19(3):337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Comello MLG. Conceptualizing the intervening roles of identity in communication effects: The prism model. In: Lasorsa D, Rodriguez A, editors. Identity and communication: New agendas in communication. Routledge; New York, NY: 2013. pp. 168–188. [Google Scholar]

- Dvir-Gvirsman S, Huesmann R, Landau S, Dubow EF, Boxer P, Shikaki K. The effects of mediated exposure to ethnic-political violence on Middle East youth's subsequent post-traumatic stress symptoms and aggressive behavior. Communication Research. doi: 10.1177/0093650213510941. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eveland WP, Jr., Cooper KE. An integrated model of communication influence on beliefs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 2013;110(Suppl. 3):14088–14095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212742110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eveland WP, Jr., Morey AC. Challenges and opportunities of panel designs. In: Bucy EP, Holbert RL, editors. The sourcebook for political communication research: Methods, measures, and analytical techniques. Routledge; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Eveland WP, Jr., Shah D, Kwak N. Assessing causality in the cognitive mediation model: A panel study of motivations, information processing, and learning during Campaign 2000. Communication Research. 2003;30(4):359–386. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio RH, Powell MC, Williams CJ. The role of attitude accessibility in the attitude-to-behavior process. Journal of Consumer Research. 1989;16(3):280–288. [Google Scholar]

- Klapper JT. The effects of mass communication. The Free Press; New York, NY: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch S. Mood adjustment via mass communication. Journal of Communication. 2003;53(2):233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch S, Dillman Carpentier F, Zillmann D. Effects of salience dimensions of informational utility on selective exposure to online news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 2003;80(1):91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch-Westerwick S. Selective exposure and reinforcement of attitudes and partisanship before a presidential election. Journal of Communication. 2012;62(4):628–642. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch-Westerwick S, Hoplamazian GJ. Gendering the self: Selective magazine reading and reinforcement of gender conformity. Communication Research. 2012;39(3):358–384. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch-Westerwick S, Meng J. Reinforcement of the political self through selective exposure to political messages. Journal of Communication. 2011;61(2):349–368. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire P. Will Americans receive a microchip implant in 2013 per Obamacare? 2012 Jul 23; Retrieved from http://www.newswithviews.com/McGuire/paul135.htm.

- Morgan M, Shanahan J, Signorielli N. Growing up with television: Cultivation processes. In: Bryant J, Oliver MB, editors. Media effects: Advances in theory and research. 3rd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 2009. pp. 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder J, Ter Bogt TFM, Raaijmakers QAW, Vollebergh W. Music taste groups and problem behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36(3):313–324. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet EC, Myers TA. Challenging the state: Transnational TV and political identity in the Middle East. Political Communication. 2010;27(4):347–366. [Google Scholar]

- Noelle-Neumann E. The spiral of silence: A theory of public opinion. Journal of Communication. 1974;24(2):43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MB, Raney AA. Entertainment as pleasurable and meaningful: Identifying hedonic and eudaimonic motivations for entertainment consumption. Journal of Communication. 2011;61(5):984–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Peter J, Valkenburg PM. Adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit internet material and notions of women as sex objects: Assessing causality and underlying processes. Journal of Communication. 2009;59(3):407–433. [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Briñol P, Priester JR. Mass media attitude change: Implications of the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In: Bryant J, Oliver MB, editors. Media effects: Advances in theory and research. 3rd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 2009. pp. 125–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin AM. Uses and gratifications perspective on media effects. In: Bryant J, Oliver MB, editors. Media effects: Advances in theory and research. 3rd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 2009. pp. 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier LM, Grenard J. Influence of a nationwide social marketing campaign on adolescent drug use. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(3):240–271. doi: 10.1080/10810731003686580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schemer C. Reinforcing spirals of negative affects and selective attention to advertising in a political campaign. Communication Research. 2012;39(3):413–434. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud NJ. Polarization and partisan selective exposure. Journal of Communication. 2010;60(3):556–576. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein C. Republic.com. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2001. Republic.com [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of intergroup relations. Nelson-Hall; Chicago: 1986. pp. 7–4. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, Peter J. The differential susceptibility to media effects model. Journal of Communication. 2013;63(2):221–243. [Google Scholar]

- van der Rijt GA, d'Haenens LSJ, Jansen RHA, de Vos CJ. Young people and music television in the Netherlands. European Journal of Communication. 2000;15(1):79–91. [Google Scholar]

- von Bertalanffy L. General systems theory: Foundations, development, applications. George Braziller; New York, NY: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- von Salisch M, Vogelgesang J, Kristen A, Oppl C. Preference for violent electronic games and aggressive behavior among children: The beginning of the downward spiral? Media Psychology. 2011;14(3):233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler SC, DeMarree KG, Petty RE. Understanding the role of the self in prime-to-behavior effects: The active-self account. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2007;11(3):234–261. doi: 10.1177/1088868307302223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. Media use and global warming perceptions: A snapshot of the reinforcing spirals. Communication Research. 2009;36(5):698–723. [Google Scholar]

- Zillmann D. Mood management through communication choices. American Behavioral Scientist. 1988;31(3):147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Zillmann D, Bryant J, editors. Selective exposure to communication. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. Cambridge University Press; Melbourne, Australia: 1994. [Google Scholar]