Abstract

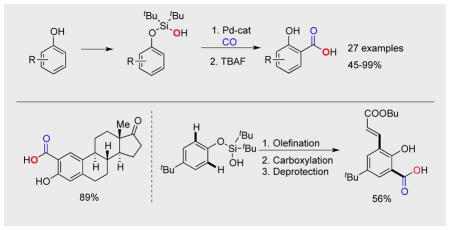

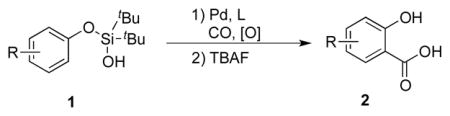

A silanol directed, palladium catalyzed C–H carboxylation reaction of phenols into salicylic acids has been developed. This method features high efficiency and selectivity, and excellent functional group tolerance. The generality of this method was demonstrated by carboxylation of estrone and by the synthesis of a bis-unsymmetrically substituted phenolic compound via iterative C–H functionalizations.

Keywords: carboxylation, palladium, phenols, salicylic acids, C–H activation

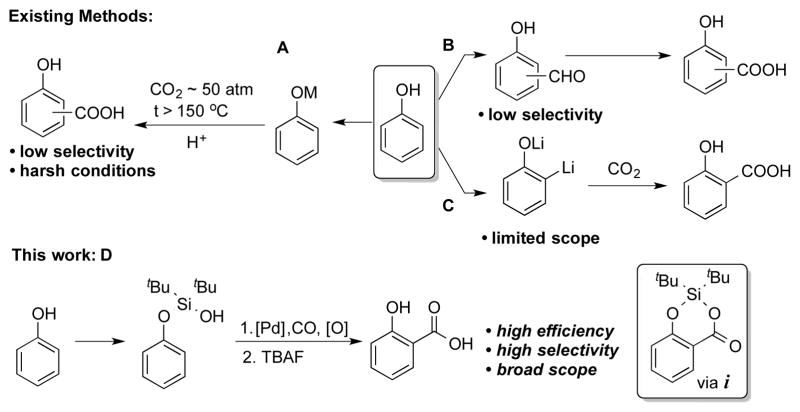

Salicylic acids (SAs) are key motifs in pharmaceutically and biologically active compounds,[1] useful synthetic intermediates,[2] as well as important building blocks in material science.[3] Due to the significance of SAs, a number of synthetic methods have been developed.[4] The Kolbe-Schmitt reaction is the most commonly used route to SAs (Figure 1, path A).[4a] Other routes include, ortho-formylation of phenols with subsequent oxidation (path B),[4b,c] and, directed ortho metalation (DoM) of phenol, followed by quenching of the formed aryllithium species with CO2 (path C).[4d] Though widely used, the aforementioned methods suffer from major limitations, such as harsh conditions, poor selectivity, and limited scope. Herein, we report a palladium catalyzed silanol directed ortho C–H carboxylation reaction of phenols toward SAs synthesis. This efficient protocol is highly selective and demonstrates excellent functional group tolerance.

Figure 1.

Methods for Synthesis of Salicylic Acid from Phenols.

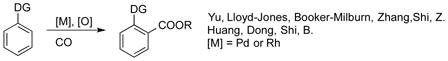

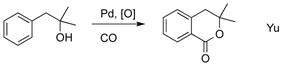

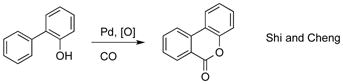

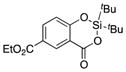

Transition metal catalyzed C–H[5] carboxylation reactions[6] employing cheap and abundant CO is attractive approach since it allows for introduction of valuable carboxyl functionality at inert, but ubiquitous in organic compounds, C–H bonds. Most reports for highly efficient and selective C–H carboxylation of arenes[7] entail the use of directing groups (eq 1).[8] Moreover, Yu, and later Shi and Cheng groups, reported a hydroxyl-directed Pd-catalyzed C–H carbonylation reactions of arenes leading to lactones and coumarins (eq 2 and 3).[9] Since no general and selective methods for conversion of phenols into SAs exist (vide supra), we thought that development of such methodology is highly justified. Previously, our group developed silanol as a powerful traceless directing group[10] for Pd-catalyzed ortho-alkenylation[10a] and oxygenation[10b] of phenols. Hence, we hypothesized that if the phenoxy silanol could undergo a Pd-catalyzed carbonylation reaction to generate intermediate i, the latter, upon a routine desilylation, would produce SAs in a regioselective manner from accessible phenols (Figure 1, path D).[11]

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

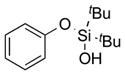

We initially tested the carboxylation reaction of 1b under Yu’s modified procedure.[9a] Under these conditions, 2b′ was obtained as a single product in 17% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Despite the low yield, the robustness of 2b′ under the carboxylation conditions, along with the cleanness of the reaction encouraged us to focus on optimization studies. It was found that only trace amounts of product were detected in a control experiment without ligand (entry 2). Accordingly, we screened different MPAA ligands in this reaction. Notably, product yield increased to 37% with Ac-Val-OH as a ligand (entry 3), among many other ligands tested (entries 4 – 6, also see Supporting Information for the complete screening), Boc-Leu-OH exhibited the best reactivity, producing 2b′ in 90% yield (entry 6). Screening other experiment parameters indicated that reducing palladium amount to 5 mol % had a deleterious effect on the yield (entry 7), and no carboxylation occurred in the absence of palladium (entry 8). Other oxidants and solvents were also examined. Cu(OAc)2, BQ and O2, which are commonly used oxidants in C–H functionalization, were ineffective (entries 9 – 11). Solvents other than DCE gave poorer results (entries 11 – 13).

Table 1.

Optimization of Reaction Conditions.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Ligand[a] | oxidant | solvent | yield, %[b] |

| 1 | L3 | AgOAc | DCE | 17 |

| 2 | / | AgOAc | DCE | <1 |

| 3 | L1 | AgOAc | DCE | 37 |

| 4 | L2 | AgOAc | DCE | 33 |

| 5 | L4 | AgOAc | DCE | 42 |

| 6 | L5 | AgOAc | DCE | 90 |

| 7[c] | L5 | AgOAc | DCE | 59 |

| 8[d] | L5 | AgOAc | DCE | 0 |

| 8 | L5 | Cu(OAc)2 | DCE | 5 |

| 9 | L5 | BQ | DCE | 3 |

| 10[e] | L5 | O2 | DCE | 7 |

| 11 | L5 | AgOAc | Dioxane | <1 |

| 12 | L5 | AgOAc | EtCN | 4 |

| 13 | L5 | AgOAc | Xylene | 20 |

L1 = Ac-Val-OH; L2 = Boc-Val-OH; L3 = (+) Menthyl(O2C)-Leu-OH; L4 = Ac-Leu-OH; L5 = Boc-Leu-OH.

GC yield, with nC15H32 as internal standard.

5 mol % Pd(OAc)2 and 10 mol % ligand was used.

No Pd(OAc)2.

O2 balloon.

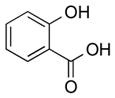

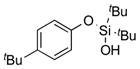

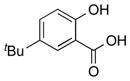

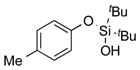

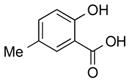

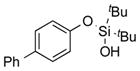

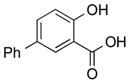

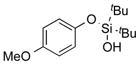

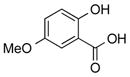

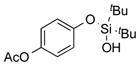

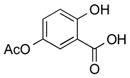

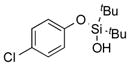

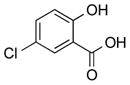

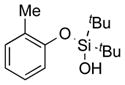

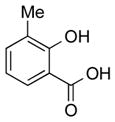

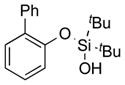

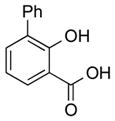

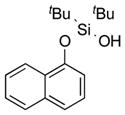

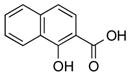

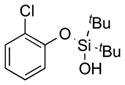

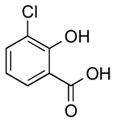

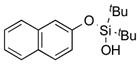

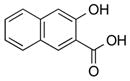

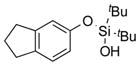

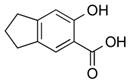

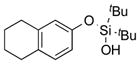

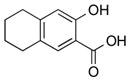

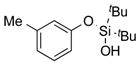

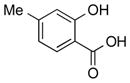

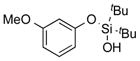

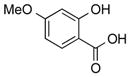

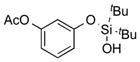

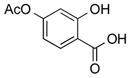

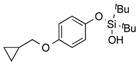

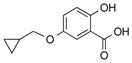

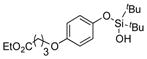

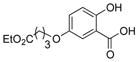

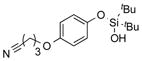

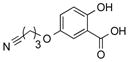

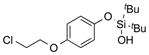

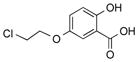

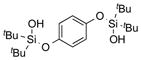

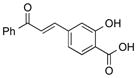

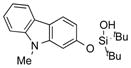

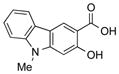

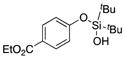

Under the optimized conditions for carboxylation, followed by a routine desilylation step, silanol 1a was converted into salicylic acid 2a in 76 % yield (Table 1, entry 1). Substrates with electron donating groups produced the corresponding SAs (2b, 2c, 2e, 2h) in good to excellent yields; whereas, those possessing electron neutral and deficient substituents generated products (2d, 2j, 2i) in slightly diminished yields. Remarkably, a number of useful functionalities, including ester (2s), nitrile (2t), aryl chlorides (2g, 2k), alkyl chloride (2u), cyclopropyl (2r), and ketone (Scheme 2, 2w) were tolerated under the reaction conditions. Notably, only desired products were isolated when other potential directing groups, such as methoxy- and acetoxy groups, were present (2e, 2f, 2p, 2q).[12] In the event where the silanol precursor contained two possible reactive sites, C–H carboxylation occurred preferentially at the sterically less demanding position (2l-p). Bis-silanol derivative 1v produced mono-acid 2v in excellent yield. Evidently, the newly installed carboxylic group electronically deactivates the aromatic ring thus preventing the second C–H carboxylation event. Importantly, substrates possessing a sensitive cinnamyl group at para- and meta-positions (1w, x) were also competent reactants producing the corresponding salicylic acids 2w, x in reasonable yields. Likewise, carbazole derivative 1y reacted smoothly to give 2y in 64% yield. In contrast, ester-possessing phenol 1z was much less reactive under these conditions (entry 26), whereas strongly electron-deficient 3-NO2- and 4-CN-substituted phenols did not react at all. Notably, this method tolerates substituents at the ortho position, as demonstrated by carboxylation of 2h (Me), 2i (Ph), 2j (naphthalene) and 2k (chloro). This is in sharp contrast with our previous report on the silanol-directed C–H olefination reaction, which showed no reactivity toward substrates possessing substituents at the ortho position.[10a]

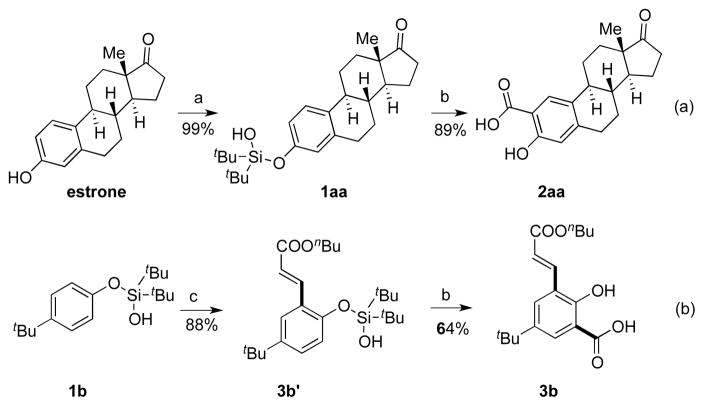

Scheme 2.

C–H Carboxylation Reaction of Complex Phenols.

[a] tBu2SiBr2 (1.1 eq), imidazole (2.2 eq.), DMF, 18 h. Then, NaHCO3 (aq), r.t., 1 h. [b] Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol %), Boc-Leu-OH (L, 20 mol %), AgOAc (3 eq.), CF3CH2OH (3 eq.), CO/Ar (1:8, balloon), DCE (0.25 M), 95 °C, 18 h. Then, TBAF (0.4 mL, 1 M), THF (2 mL), r.t., 30 min. [c] alkene (1.2 eq.), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol %), (+)Menthyl(O2C)-Leu-OH (L1, 20 mol %), AgOAc (4 eq.), DCE (0.1 M), 100 °C, 48 h.

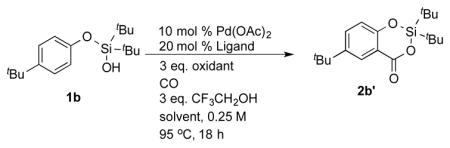

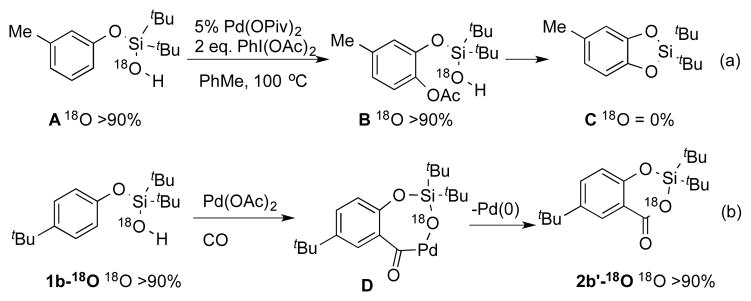

Next, we were eager to clarify the reaction pathway. Hence, in our previously developed silanol-directed C–H oxygenation of phenols,[10b] with the aid of 18O labeling study, we established that the silanol oxygen was not incorporated into the oxygenated product C (Scheme 1, a). Accordingly, we prepared 1b-18O and subjected it to our C–H carboxylation reaction conditions. In contrast to the previous report, this study revealed complete retention of 18O label in the silacycle 2b′ (Scheme 1, b). Therefore, we propose that the key intermediate D, which was generated upon C–H activation of 1b and migratory insertion of CO, undergoes reductive elimination to produce the 18O incorporated product 2b′-18O.[13]

Scheme 1.

18 O Labelling Studies.

Finally, this novel carboxylation method was tested on more complex phenols. Thus, estrone was first converted into its silanol derivative 1aa in almost quantitative yield. The latter underwent a smooth carboxylation/desilylation sequence to produce 2aa as a single isomer in 89 % yield (Scheme 2, a). Considering the importance of multi-substituted phenols in bioactive compounds,[14] we probed our method toward the synthesis of bis-unsymmetrically functionalized phenolic compound. Hence, after two iterative C–H functionalization operations, olefination[10a] followed by carboxylation, the desired phenolic compound 3b was obtained in good overall yield (Scheme 2, b). To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first example of a stepwise unsymmetrical C–H functionalization of phenols.[15]

In conclusion, a general method for synthesis of salicylic acids from phenols has been developed. This method features high efficiency, broad substrate scope, and high regioselectivity. Mechanistic study revealed the ester oxygen atom of the carboxylic group originates from silanol group. The feasibility for employment of this method for a late stage functionalization of Moreover, two iterative C–H functionalization reactions, olefination[10a] and carboxylation, allowed for synthesis of o,o′- bis-unsymmetrically substituted phenolic compound. We envision that this approach will become a useful method toward synthesis of salicylic acids from phenols.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

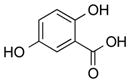

| entry | silanol | product | yield,% | ||

| 1 |

|

1a |

|

2a | 76 |

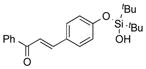

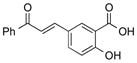

| 2 |

|

1b |

|

2b | 91 |

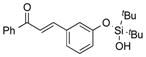

| 3 |

|

1c |

|

2c | 92 |

| 4 |

|

1d |

|

2d | 65 |

| 5 |

|

1e |

|

2e | 80 |

| 6 |

|

1f |

|

2f | 71 |

| 7 |

|

1g |

|

2g | 49 |

| 8 |

|

1h |

|

2h | 89 |

| 9 |

|

1i |

|

2i | 63 |

| 10 |

|

1j |

|

2j | 66 |

| 11 |

|

1k |

|

2k | 45 |

| 12 |

|

1l |

|

2l | 85[c] |

| 13 |

|

1m |

|

2m | 98[d] |

| 14 |

|

1n |

|

2n | 99 |

| 15 |

|

1o |

|

2o | 92 |

| 16 |

|

1p |

|

2p | 57 |

| 17 |

|

1q |

|

2q | 69 |

| 18 |

|

1r |

|

2r | 77 |

| 19 |

|

1s |

|

2s | 76 |

| 20 |

|

1t |

|

2t | 81 |

| 21 |

|

1u |

|

2u | 79 |

| 22 |

|

1v |

|

2v | 91 |

| 23 |

|

1w |

|

2w | 62 |

| 24 |

|

1x |

|

2x | 66 |

| 25 |

|

1y |

|

2y | 64 |

| 26 |

|

1z |

|

2z′ | (14)[e] |

Reacton conditions: Silanol 1 (0.2 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (0.02 mmol, 10 mol %), Boc-Leu-OH (L, 0.04 mmol, 20 mol %), AgOAc (0.6 mmol, 3 eq.), CF3CH2OH (0.6 mmol, 3 eq.), CO/Ar (1:8, balloon), DCE (0.8 mL, 0.25 M), 95 °C, 18 h. See Supporting Information for details.

isolated yield.

major : minor = 2 : 1.

major : minor = 4 : 1.

NMR yield of silacycle after the first step.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (GM-64444) and National Science Foundation (CHE-1362541) for financial support. We also thank Mr. Marvin Parasram for helpful discussions during preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- 1.a) Elwood P, Morgan M, Brown G, Pickering J. BMJ. 2005;330:1440–1441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7505.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) El-Kabbani O, Scammells PJ, Gosling J, Dhagat U, Endo S, Matsunaga T, Soda M, Hara A. J Med Chem. 2009;52:3259–3264. doi: 10.1021/jm9001633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hawley SA, Fullerton MD, Ross FA, Schertzer JD, Chevtzoff C, Walker K, Peggie MW, Zibrova D, Green KA, Mustard KJ, Kemp BK, Sakamoto K, Steinberg GR, Hardie DG. Science. 2012;336:918–922. doi: 10.1126/science.1215327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Luo J, Preciado S, Larrosa I. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:4109–4112. doi: 10.1021/ja500457s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ooguri A, Nakai K, Kurahashi T, Matsubara S. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13194–13195. doi: 10.1021/ja904068p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ebe Y, Nishimura T. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9284–9287. doi: 10.1021/ja504990a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Wang C, Piel I, Glorius F. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4194–4195. doi: 10.1021/ja8100598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Caulder DL, Brulckner C, Powers RE, König S, Parac TN, Leary LA, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8923–8938. doi: 10.1021/ja0104507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Roberts MC, Hanson MC, Massey AP, Karren EA, Kiser PF. Adv Mater. 2007;19:2503–2507. [Google Scholar]; c) Barman S, Mukhopadhyay SK, Behara KK, Dey S, Singh NDP. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:7045–7054. doi: 10.1021/am500965n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Furukawa H, Cordova KE, O’Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Science. 2013;341:974–986. doi: 10.1126/science.1230444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindsey A, Jeskey H. Chem Rev. 1957;57:583–620.Hansen T, Skattebøl L. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:3357–3358.Chakraborty D, Gowda RR, Malik P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:6553–6556.Posner GH, Canella KA. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:2571–2573.Recently, Yu group published an elegant synthesis of salicylic acid via C–H hydroxygenation of benzoic acid, see: Zhang YH, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14654–14655. doi: 10.1021/ja907198n.

- 5.For general reviews on transition metal-catalyzed C–H activation reactions, see: Wencel-Delord J, Droge T, Liu F, Glorius F. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:4740–4761. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15083a.Enthaler S, Company A. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:4912–4924. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15085e.Xu LM, Li BJ, Yang Z, Shi ZJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:712–733. doi: 10.1039/b809912j.Lyons TW, Sanford MS. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1147–1169. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e.Beccalli EM, Broggini G, Martinelli M, Sottocornola S. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5318–5365. doi: 10.1021/cr068006f.Alonso DA, Nájera C, Pastor IM, Yus M. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:5724–5741. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000470.C–H Activation; Yu J-Q, Shi Z-J, editors. Topics in Current Chemistry. Vol. 292. Springer; Berlin: 2010. Yeung CS, Dong VM. Chem Rev. 2011;111:1215. doi: 10.1021/cr100280d.Seregin IV, Gevorgyan V. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1173–1193. doi: 10.1039/b606984n.

- 6.For the first stoichiometric Pd-mediated C–H carboxylation reaction, see: Fujiwara Y, Kawauchi T, Taniguchi H. J C S Chem Comm. 1980:220–221.

- 7.For examples of direct C-H carboxylation, see: Lu W, Yamaoka Y, Taniguchi Y, Kitamura T, Takaki K, Fujiwara Y. J Organomet Chem. 1999;580:290–294.Grushin VV, Marshall WJ, Thorn DL. Adv Synth Catal. 2001;343:161–165.

- 8.For examples of directed C–H carboxylation, see: Giri R, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14082–10483. doi: 10.1021/ja8063827.Giri R, Lam JK, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:686–693. doi: 10.1021/ja9077705.Houlden CE, Hutchby M, Bailey CD, Ford JG, Tyler SNG, Gagné MR, Lloyd-Jones GC, Booker-Milburn KI. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:1830–1833. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805842.Angew Chem. 2009;121:1862–1865.Guan Z, Ren Z, Spinella SM, Yu S, Liang Y, Zhang X. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:729–733. doi: 10.1021/ja807167y.Li H, Cai G-C, Shi Z-J. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:10442–10446. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00451k.Xie P, Xie Y, Qian B, Zhou H, Xia C, Huang H. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9902–9905. doi: 10.1021/ja3036459.Mo F, Trzepkowski LJ, Dong G. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:13075–13079. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207479.Angew Chem. 2012;124:13252–13256.Liu B, Jiang HZ, Shi BF. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:2538–2542. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00084f.For a leading book on carbonylation reactions, see: Beller M, editor. Catalytic Carbonylation Reactions Vol. 18; Topics in Current Chemistry. Springer; Berlin: 2006.

- 9.Lu Y, Leow D, Wang X, Engle KM, Yu JQ. Chem Sci. 2011;2:967–971.Luo S, Luo F, Zhang X, Shi ZJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;58:10598–10601. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304295.Angew Chem. 2013;125:10792–10795.See also: Lee TH, Jayakumar J, Cheng CH, Chuang SC. Chem Comm. 2013;49:11797–11799. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47197g.For a ruthenium catalyzed, hydroxyl group directed carbonylation reaction, see: Inamoto K, Kondo Y. Org Lett. 2013;15:3962–3965. doi: 10.1021/ol401734m.

- 10.Huang C, Chattopadhyay B, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12406–12409. doi: 10.1021/ja204924j.Huang C, Ghavtadze N, Chattopadhyay B, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:17630–17633. doi: 10.1021/ja208572v.For other examples of C–H activation with a silicon tether, see: Chernyak N, Dudnik AS, Huang C, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8270–8272. doi: 10.1021/ja1033167.Dudnik AS, Chernyak N, Huang C, Gevorgyan V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8729–8732. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004426.Angew Chem. 2010;122:8911–8914.Huang C, Chernyak N, Dudnik AS, Gevorgyan V. Adv Synth Catal. 2011;353:1285–1305. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201000975.Huang C, Ghavtadze N, Godoi B, Gevorgyan V. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:9789–9792. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201616.Sarkar D, Melkonyan FS, Gulevich AV, Gevorgyan V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:10800–10804. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304884.Angew Chem. 2013;125:11000–11004.Wang C, Ge H. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:14371–14374. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103171.Lee S, Lee H, Tan KL. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:18778–18781. doi: 10.1021/ja4107034.Ghavtadze N, Melkonyan FS, Gulevich AV, Huang C, Gevorgyan V. Nat Chem. 2014;6:122–125. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1841.Li Q, Driess M, Hartwig JF. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:8471–8474. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404620.Angew Chem. 2014;126:8611–8614.Li B, Driess M, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:6586–6589. doi: 10.1021/ja5026479.Simmons EM, Hartwig JF. Nature. 2012;483:70–73. doi: 10.1038/nature10785.Kuninobu Y, Nakahara T, Takeshima H, Takai K. Org Lett. 2013;15:426–428. doi: 10.1021/ol303353m.Gulevich AV, Melkonyan FS, Sarkar D, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:5528–5531. doi: 10.1021/ja3010545.Kuznetsov A, Onishi Y, Inamoto Y, Gevorgyan V. Org Lett. 2013;15:2498–2501. doi: 10.1021/ol400977r.For two leading reviews on removable groups directed organic reactions, see: Rousseau G, Breit B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:2450–2494. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006139.Angew Chem. 2011;123:2498–2543.Zhang F, Spring DR. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:6906–6919. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00137k.

- 11.For a single example of non-selective (o : p = 1 : 9) direct C–H carboxylation reaction of phenol, see: Ohashi S, Sakaguchi S, Ishii Y. Chem Comm. 2005:486–488. doi: 10.1039/b411934g.

- 12.For alkoxy directing groups, see: Li G, Leow GD, Wan L, Yu J-Q. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;52:1245–1247. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207770.Angew Chem. 2012;125:1283–1285.Oyamada J, Nishiura M, Hou Z. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:10720–10723. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105636.Angew Chem. 2011;123:10908–10911.Iglesias Á, Álvarez R, de Lera ÁR, Muñiz K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:2225–2228. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108351.Angew Chem. 2012;124:2268–2271.Liskey CW, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:12422–12425. doi: 10.1021/ja305596v.Kawamorita S, Ohmiya H, Hara K, Fukuoka A, Sawamura M. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5058–5059. doi: 10.1021/ja9008419.Ghaffari B, Preshlock SM, Plattner DL, Staples RJ, Maligres PE, Krska SW, Maleczka RE, Jr, Smith MR., III J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:14345–14348. doi: 10.1021/ja506229s.For OAc as a directing group, see: Xiao B, Fu Y, Xu J, Gong TJ, Dai JJ, Yi J, Liu L. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:468–469. doi: 10.1021/ja909818n.Gensch T, Rönnefahrt M, Czerwonka R, Jäger A, Kataeva O, Bauer I, Knölker H. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:770–776. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103576.

- 13.For related studies, see: Orito K, Horibata A, Nakamura T, Ushito H, Nagasaki H, Yuguchi M, Yamashita S, Tokuda M. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14342–14343. doi: 10.1021/ja045342+.Milstein D. Acc Chem Res. 1988;21:428–434.On the other hand, the possibility that CO inserts into Pd–O bond, followed by reductive elimination could not be excluded, see: Bernard KA, Atwood JD. Organometallics. 1989;8:795–800.Hu Y, Liu J, Lu Z, Luo X, Zhang H, Lan Y, Lei A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3153–3158. doi: 10.1021/ja909962f.

- 14.a) Hallowell RW, Horton MR. Drugs. 2014;74:443–450. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0190-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Marcén R. Drugs. 2009;69:2227–2243. doi: 10.2165/11319260-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Whiting DA. Nat Prod Rep. 2001;18:583–606. doi: 10.1039/b003686m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.For bis-unsymmetrically C–H functionalization of arenes, see: Wang H, Li G, Engle KM, Yu JQ, Davies HML. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:6774–6777. doi: 10.1021/ja401731d.Rosen BR, Simke LR, Thuy-Boun PS, Dixon DD, Yu JQ, Baran PS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:7317–7320. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303838.Angew Chem. 2013;125:7458–7461.Li S, Chen G, Feng CG, Gong W, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:5267–5270. doi: 10.1021/ja501689j.Beck EM, Hatley R, Gaunt MJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:3004–3007. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705005.Angew Chem. 2008;120:3046–3049.See also: ref 10g.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.