Abstract

Variations in the carbon isotope signature of leaf dark-respired CO2 (δ13CR) within a single night is a widely observed phenomenon. However, it is unclear whether there are plant functional type differences with regard to the amplitude of the nighttime variation in δ13CR. These differences, if present, would be important for interpreting the short-term variations in the stable carbon signature of ecosystem respiration and the partitioning of carbon fluxes. To assess the plant functional type differences relating to the magnitude of the nighttime variation in δ13CR and the respiratory apparent fractionation, we measured the δ13CR, the leaf gas exchange, and the δ13C of the respiratory substrates of 22 species present in the agricultural-pastoral zone of the Songnen Plain, northeast China. The species studied were grouped into C3 and C4 plants, trees, grasses, and herbs. A significant nocturnal shift in δ13CR was detected in 20 of the studied species, with the magnitude of the shift ranging from 1‰ to 5.8‰. The magnitude of the nighttime variation in δ13CR was strongly correlated with the daytime cumulative carbon assimilation, which suggests that variation in δ13CR were influenced, to some extent, by changes in the contribution of malate decarboxylation to total respiratory CO2 flux. There were no differences in the magnitude of the nighttime variation in δ13CR between the C3 and C4 plants, as well as among the woody plants, herbs and graminoids. Leaf respired CO2 was enriched in 13C compared to biomass, soluble carbohydrates and lipids; however the magnitude of enrichment differed between 8 pm and 4 am, which were mainly caused by the changes in δ13CR. We also detected the plant functional type differences in respiratory apparent fractionation relative to biomass at 4 am, which suggests that caution should be exercised when using the δ13C of bulk leaf material as a proxy for the δ13C of leaf-respired CO2.

Introduction

The stable C isotope composition (δ13C) has been widely used to trace the carbon flow within ecosystem components or between the ecosystem and the atmosphere [1–7]. The applications of stable carbon isotope technique require a mechanistic understanding of the temporal and spatial variation in the δ13C signature of component fluxes [8–10]. As an important component of ecosystem carbon fluxes, leaf respired CO2 has been reported to vary substantially in its carbon isotope composition at diurnal timescale [11–15]. Unfortunately, we still lack a comprehensive understanding of the processes controlling the dynamics in the δ13C signature of leaf respired CO2 [9, 16].

It has been extensively reported that δ13CR varied substantially, up to 14.8‰, on a diurnal timescale [12, 13, 17, 18]. Several mechanisms have been developed to explain short-term variation in δ13CR. Firstly, intramolecular 13C distribution is not homogeneous in hexose molecules, which combined with changes in the relative contribution of the metabolic pathways to the respiration could lead to variation in δ13CR [14, 19–22]. Secondly, shifts in δ13CR can be attributed to the changes in the contribution of malate (13C-enriched) decarboxylation to the overall respiratory flux [8, 23]. Thirdly, changes in the use of the respiratory substrates having different δ13C may subsequently affect δ13CR [16, 18]. Finally, short variation in carbohydrate pool size may also influence δ13CR through affecting the allocation of respiratory intermediates [24]. The results of previous study showed substantial intraspecific and interspecific differences in the amplitude of the short-term variation in δ13CR [14, 18, 25]. Intraspecific differences in the range of the diurnal variation in δ13Cl are caused mainly by the availability of resources associated changes in the substrate availability and the allocation of the respiratory intermediates [25]. The findings of previous studies by Werner et al. (2007) and Priault et al. (2009) indicated large diurnal variations in the δ13CR of slow-growing aromatic plants, whereas no apparent diurnal shift was found in the δ13CR in temperate trees and fast-growing herbs. These results highlight the potential plant functional type differences relating to the extent of the variation in δ13CR on a diurnal timescale [11, 14, 22]. However, plant functional type differences in the magnitude of short-term variation in δ13CR need to be further explored, especially for C3 and C4 species which differed substantially in the magnitude of heterogeneous 13C distribution within hexose molecules [21, 26].

Leaf dark-respired CO2 is often enriched in 13C compared with leaf bulk tissue or other potential respiratory substrates, such as starch, soluble carbohydrates, and others [27–29]. This phenomenon is attributed mainly to non-homogeneous 13C distribution among the carbon atoms within the hexose molecules and the incomplete oxidation of hexoses. However, the phenomenon is also attributed partially to the utilization of isotopically different respiratory substrates [21, 24, 30]. Because of the intramolecular 13C/12C differences, CO2 that evolved from pyruvate decarboxylation contains more 13C relative to that derived from acetyl-CoA oxidation [31, 32]. Depending on substrate availability, 13C-depleted acetyl-CoA could be used for the biosynthesis of lipids and secondary compounds, or decarboxylation in the TCA cycle to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Therefore, the incomplete oxidation of acetyl-CoA could lead to 13C enrichment in leaf dark-respired CO2 relative to respiratory substrates. The plant functional types differed substantially with regard to the allocation of 13C-depleted compounds. Trees, for instance, allocated proportionally more acetyl-CoA to the synthesis of lipids and lignin than did grasses [14, 26]. This could lead to the leaf-respired CO2 in trees being more enriched in 13C in comparison with the putative respiratory substrates or the bulk leaf material. Indeed, plant functional type differences in respiratory apparent fractionation have been reported between C3 and C4 species, but not between woody plants and C3 herbs [15, 16]. However, these findings were derived from meta-analysis of results obtained under various growing habitats and using different methods, which makes the conclusions unreliable. Therefore, the existence of plant functional type differences with regard to respiratory apparent fractionation needs to be further verified and, if they do exist, we need to incorporate these into the flux partitioning.

The vegetation of the agricultural-pastoral zone of the Songnen Plain is characterized as mosaics of grassland and cultivated land, dominated mainly by C3 species and C4 species, respectively. We measured the δ13CR and δ13C of the putative primary respiratory substrates of 22 species at 8 pm and 4 am. The leaf gas-exchange parameters, including net assimilation rate, stomatal conductance, and nighttime respiration rate were also measured. The plant species were grouped into C3 and C4 species, trees, graminoids, and herbs. The objectives of the present study were to assess the plant functional type differences in the range of nighttime variation in δ13CR and the respiratory apparent fractionation relative to the bulk leaf material and the putative respiratory substrates.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

No specific permissions were required for the field studies described, because the Songnen Grassland Ecological Research Station is a department of the Northeast Normal University. No specific permissions were required for the study either, as it was conducted in accordance with the guidelines set by the Northeast Normal University. No specific permissions were required for the locations or the activities. No location was privately owned or protected in any way, and the field studies did not involve endangered or protected species.

Study site

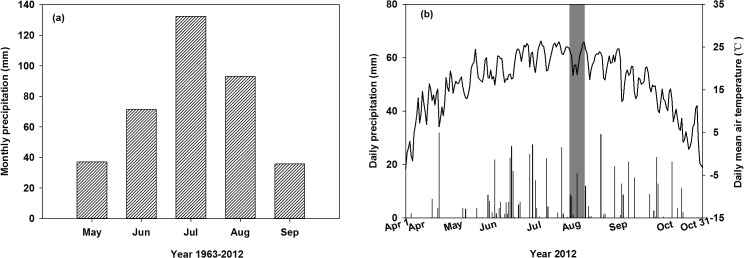

The study was conducted in the agricultural-pastoral zone of the Songnen Plain (44°40′–44°44′N, 123°44′–123°47′E, elevation 138–144 m) in northeast China. The study area has a semiarid continental climate, with a mean annual temperature of 6.4°C. The mean annual rainfall is 471 mm, with over 70% of the precipitation occurs from June to August (Fig 1A). Drought, especially spring drought, occurs frequently in the studied area during the growing season; however there is no fixed drought period. The duration of the frost-free season is approximately 150 days. Detailed information on daily precipitation and daily temperature in 2012 is provided in Fig 1B. The main soil type of the study area is chernozem, with a soil organic carbon content of 2.0% and a soil total nitrogen content of 0.15% [33]. The vegetation in the study area is characterized as mosaics of grassland and cultivated land. The grassland is dominated by Leymus chinensis, while Phragmites australis and Chloris virgata are present in abundance[34]. The major crops on the cultivated land are Zea mays, Setaria italica, Helianthus annuus, and Sorghum bicolor. We studied 22 plant species, representative of the major species present on the grassland and the cultivated land. The details of the species studied are provided in Table 1. The field studies were conducted from July 25th to August 5th in 2012, which is the peak biomass season for the study area. None of the studied species showed signs of senescence. Information on the development stage of the studied species is provided in Table 1.

Fig 1. Growing season average monthly precipitation (mm) from 1963 to 2012 (a), and daily precipitation (mm) and daily mean air temperature (°C) from April 1th to October 31th in 2012 (b).

The shaded area in panel b denotes the field sampling period.

Table 1. Information on species studied.

List of plant species studied, and their photosynthetic pathway, classification and phenological phase.

| Species | Photosynthetic pathway | Functional type | Class | Phenological phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leymus chinensis | C3 | Graminoids | Monocotyledoneae | Fructescence |

| Phragmites australis | C3 | Graminoids | Monocotyledoneae | Florescence |

| Lespedeza bicolor | C3 | Trees | Dicotyledoneae | Florescence |

| Malus asiatica | C3 | Trees | Dicotyledoneae | Fructescence |

| Populus simonii | C3 | Trees | Dicotyledoneae | Post-fruiting vegetative stage |

| Prunus salicina | C3 | Trees | Dicotyledoneae | Fructescence |

| Chenopodium glaucum | C3 | Herbs | Dicotyledoneae | Florescence |

| Glycine max | C3 | Herbs | Dicotyledoneae | Flowering and pod formation stage |

| Helianthus annuus | C3 | Herbs | Dicotyledoneae | Florescence |

| Saussurea amara | C3 | Herbs | Dicotyledoneae | Florescence |

| Vigna radiata | C3 | Herbs | Dicotyledoneae | Flowering and pod formation stage |

| Vigna unguiculata | C3 | Herbs | Dicotyledoneae | Flowering and pod formation stage |

| Xanthium sibiricum | C3 | Herbs | Dicotyledoneae | Florescence |

| Chloris virgata | C4 | Graminoids | Monocotyledoneae | Florescence |

| Echinochloa crusgalli | C4 | Graminoids | Monocotyledoneae | Florescence |

| Hemarthria altissima | C4 | Graminoids | Monocotyledoneae | Heading stage |

| Panicum miliaceum | C4 | Graminoids | Monocotyledoneae | Florescence |

| Setaria italica | C4 | Graminoids | Monocotyledoneae | Florescence |

| Setaria viridis | C4 | Graminoids | Monocotyledoneae | Florescence |

| Sorghum bicolor | C4 | Graminoids | Monocotyledoneae | Elongation stage |

| Zea mays | C4 | Graminoids | Monocotyledoneae | Tasseling stage |

| Amaranthus retroflexus | C4 | Herbs | Dicotyledoneae | Florescence |

Leaf gas-exchange measurement

Leaf photosynthesis was measured every three hours, from 6 am to 6 pm, using a LI-6400 infrared gas-exchange analyzer (LI-COR Biosciences Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). We selected fully expanded leaves from the sunny side for leaf photosynthetic rate measurements. Before each measurement, the leaf chamber conditions were set to match the environmental conditions, including the photosynthetically active radiation, air temperature, and relative humidity. Leaf respiration rates at 8 pm and 4 am were measured under zero light intensity. The leaf photosynthesis and respiration measurements for each species were conducted on five randomly selected plants.

Collection of leaf-respired CO2

Leaf-respired CO2 was collected in the field using the gas-tight syringe incubation method [11]. In brief, young and fully expanded leaves (comparable to those used to measure the photosynthesis and the respiration rates), were detached and placed inside a gas-tight syringe barrel. The syringe barrel was subsequently flushed with CO2-free air to remove the background CO2. The syringe barrel was then sealed and incubated for 15 min to allow for the buildup of leaf-respired CO2. After the incubation, 5 ml of air, containing leaf-respired CO2, was injected into a 12 ml vial. The vial was filled with helium and fitted with septum caps. For each studied species, the leaf-respired CO2 was collected twice (8 pm and 4 am) during a single night. For the period of field sampling, sunset time ranged from 7:17 pm to 7:04 pm, therefore the collection of leaf-respired CO2 at 8 pm was conducted at least 40 min after sunset and in the darkness. The leaf-respired CO2 was sampled each time on five randomly selected plants or populations.

Lipids, soluble carbohydrates, and starch extractions

Simultaneously with the leaf-respired CO2 sampling, we collected leaves for measuring the carbon isotope composition of leaf bulk materials and potential respiratory substrates. The collected leaves were comparable (age and canopy position, etc.) with those used for the leaf photosynthesis measurements. The collected leaves were immersed in liquid nitrogen to stop the metabolic activities. They were subsequently stored at -80°C in a deep freezer before being freeze-dried with a Labconco freeze drier (Labconco Kansas City, MO, USA). A ball mill (MM 400 Retsch, Haan, Germany) was used to grind the freeze-dried leaves into fine powder.

We used the protocols described by Wanek et al. (2001) and Göttlicher et al. (2006) [35, 36] for the extraction of lipids, soluble carbohydrates, and starch. In brief, the powdered leaf material was extracted with methanol/chloroform/water (MCW; 12:5:3, v/v/v). After centrifugation, the chloroform and the deionized water were added to the supernatant for phase separation. The chloroform phase (containing lipids) was dried in a ventilation device and subsequently analyzed for the carbon isotope composition.

The upper water phase (containing soluble carbohydrates) was transferred into a reaction vial and oven dried for carbohydrate extraction. The residue was re-dissolved in deionized water. After centrifugation, the phase containing the soluble carbohydrates was purified by an ion-exchange column, including both anion- and cation-exchange resin. The eluent was collected and oven dried, and the carbon isotope composition was subsequently analyzed, using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer.

The plant materials were re-extracted with MCW to remove the residual lipids and the soluble carbohydrates. After the starch in the plant materials had been gelatinized and hydrolyzed, the aqueous phase was separated from the pellet by centrifugation. The upper aqueous phase was subsequently purified by a centrifugal filter unit (Microcon YM-10; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The filtrate containing glucose originated from starch was oven dried in a tin capsule and then analyzed for the carbon isotope composition.

Carbon isotope ratio analysis

All carbon isotope ratio analyses were performed using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Isoprime 100, Isoprime Ltd., Manchester, UK). The precision of repeated δ13C measurements on solid and gaseous working standards was < 0.1‰. The C isotope ratios are reported in parts per thousand relative to Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) as

Respiratory apparent 13C/12C fractionation

Respiratory apparent 13C/12C fractionation, relative to potential respiratory substrates, was calculated as:

| (1) |

where ΔR,X represents the respiratory apparent 13C/12C fractionation, relative to substrate X, and δ13CX represents the carbon isotope composition of substrate X. X represents the leaf bulk materials, lipids, starch, or soluble carbohydrates, while δ13CR represents δ13C of the leaf-respired CO2.

Statistical analysis

We used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess the differences between the photosynthetic pathways in the range of the nighttime variation of δ13CR, the leaf net CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (g s), C i/C a, and the respiratory rate (R). Linear regression analysis was employed to assess the dependence of the magnitude of the nighttime variation in δ13CR on the cumulative carbon assimilation. One-way analysis of variance was conducted to assess the plant functional type differences with regard to the leaf gas-exchange parameters, the magnitude of the nocturnal shifts in δ13CR, and the nighttime respiratory apparent fractionation. The Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) (version 13.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Data are reported as mean ± 1 standard error.

Results

Leaf gas exchange

For the species studied, the maximum leaf net CO2 assimilation rate (Amax) in the C3 species varied from 15.1±1.2 to 38.4±5.8 μmol m-2 s-1; whereas it ranged from 22.3±1.7 to 33.7±1.6 μmol m-2 s-1 in the C4 plants (Table 2). The average Amax value in the C4 plants (28.1 μmol m-2 s-1) was greater than it was in the C3 plants (22.4 μmol m-2 s-1) (Table 3). The mean leaf net CO2 assimilation rate (Mean A) varied substantially between 9.6±0.4 and 24.0±0.5 μmol m-2 s-1 (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences in Mean A between the C3 and C4 species (Table 3). Moreover, no apparent differences in Amax and Mean A were detected among the different plant functional types (Table 3).

Table 2. Leaf gas-exchange data.

Maximum leaf net CO2 assimilation rate ( Amax, μmol m-2 s-1 ), mean leaf net CO2 assimilation rate (Mean A, μmol m-2 s-1 ), maximum stomatal conductance (g smax, mol m-2 s-1), mean ratio of intercellular air space to ambient CO2 concentration (Mean C i/C a), and nighttime mean respiratory rate (Mean R, μmol m-2 s-1) of the species studied. Data are reported as mean ± 1 SE.

| Species | Amax | Mean A | g smax | Mean C i/C a | Mean R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. chinensis | 19.9±3.99 | 11.8±0.82 | 0.295±0.022 | 0.75±0.01 | 1.32±0.16 |

| P. australis | 17.2±0.35 | 11.8±0.35 | 0.268±0.011 | 0.71 ±0.01 | 0.71 ±0.08 |

| L. bicolor | 22.6±1.87 | 12.2±0.67 | 0.586±0.047 | 0.78±0.01 | 2.07 ±0.26 |

| M. asiatica | 22.3±0.90 | 17.0±0.63 | 0.446±0.017 | 0.69±0.01 | 0.74 ±0.09 |

| P. simonii | 23.2±0.32 | 17.1±0.52 | 0.511±0.041 | 0.73±0.03 | 1.22 ±0.11 |

| P. salicina | 15.3±1.65 | 11.2±0.75 | 0.531±0.057 | 0.65±0.01 | 0.51 ±0.06 |

| C. glaucum | 28.8±1.04 | 21.1±0.43 | 0.943±0.051 | 0.80 ±0.01 | 1.28 ±0.13 |

| G. max | 17.0±0.54 | 10.8±0.49 | 0.098±0.005 | 0.20±0.03 | 1.45±0.11 |

| H. annuus | 21.1±0.13 | 13.1±0.28 | 0.128±0.002 | 0.44 ±0.01 | 1.10 ±0.10 |

| S. amara | 15.1±1.20 | 9.6 ±0.36 | 0.443±0.022 | 0.82 ±0.01 | 0.73 ±0.17 |

| V. radiata | 26.3±2.98 | 14.8±1.64 | 0.247±0.009 | 0.81 ±0.01 | 2.22±0.17 |

| V. unguiculata | 23.9±4.90 | 15.2±2.66 | 0.712±0.072 | 0.59 ±0.14 | 1.54 ±0.17 |

| X. sibiricum | 38.4±5.80 | 21.2±1.20 | 0.814±0.083 | 0.79 ±0.02 | 2.12 ±0.13 |

| C. virgata | 28.1±1.71 | 15.5±1.14 | 0.179±0.005 | 0.42 ±0.03 | 0.91 ±0.13 |

| E. crusgalli | 22.6±1.34 | 13.1±0.20 | 0.212±0.017 | 0.49 ±0.03 | 0.87 ±0.08 |

| H. altissima | 22.3±1.68 | 13.8±1.57 | 0.146±0.015 | 0.49 ±0.03 | 1.36 ±0.24 |

| P. miliaceum | 27.9±0.31 | 18.1±0.28 | 0.204±0.019 | 0.41 ±0.03 | 1.54 ±0.07 |

| S. italica | 30.8±2.27 | 18.0±0.63 | 0.247±0.013 | 0.41 ±0.03 | 0.82 ±0.40 |

| S. viridis | 27.6±1.88 | 15.3±0.57 | 0.199±0.007 | 0.49 ±0.01 | 1.15 ±0.11 |

| S. bicolor | 26.2±1.34 | 17.0±0.47 | 0.183±0.034 | 0.27 ±0.02 | 1.45 ±0.16 |

| Z. mays | 33.7±1.62 | 23.6 ±0.93 | 0.367±0.051 | 0.54 ±0.06 | 0.82 ±0.05 |

| A. retroflexus | 33.3±0.53 | 24.0±0.49 | 0.520±0.040 | 0.59 ±0.03 | 1.80 ±0.10 |

Table 3. Statistical data.

The df and P values from the photosynthetic pathway and the plant functional type differences in the maximum leaf net CO2 assimilation rate ( Amax, μmol m-2 s-1 ), the mean leaf net CO2 assimilation rate (Mean A, μmol m-2 s-1 ), maximum stomatal conductance (g smax, mol m-2 s-1), mean ratio of leaf internal to ambient CO2 concentration (Mean Ci/Ca), nighttime mean respiration rate (Mean R, μmol m-2 s-1), magnitude of nocturnal shift in δ13CR (Variation in δ13CR), and respiratory apparent 13C/12C fractionation (‰) comparative to biomass (ΔR, biomass), soluble carbohydrates (ΔR, sugar), starch (ΔR, starch) and lipids (ΔR, lipid) at 8 pm and 4 am, respectively.

| Photosynthetic pathway | Functional type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | P | df | P | |

| Amax | 1 | 0.03 | 2 | 0.40 |

| Mean A | 1 | 0.39 | 2 | 0.77 |

| g s max | 1 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.02 |

| Mean Ci/Ca | 1 | <0.01 | 2 | 0.09 |

| Mean R | 1 | 0.59 | 2 | 0.14 |

| Variation in δ13CR | 1 | 0.07 | 2 | 0.29 |

| ΔR, biomass-8pm | 1 | 0.90 | 2 | 0.78 |

| Δ R, biomass-4am | 1 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.52 |

| ΔR, sugar-8pm | 1 | <0.01 | 2 | 0.09 |

| Δ R, sugar-4am | 1 | 0.22 | 2 | 0.27 |

| Δ R, starch-8pm | 1 | 0.89 | 2 | 0.60 |

| Δ R, starch-4am | 1 | 0.11 | 2 | 0.33 |

| Δ R, lipid-8pm | 1 | <0.01 | 2 | <0.01 |

| Δ R, lipid-4am | 1 | <0.01 | 2 | <0.01 |

The maximum daily stomatal conductance (g smax) varied from 0.10±0.01 to 0.94±0.05 mol m-2 s-1. Moreover, the apparent differences in g smax were detected between the C3 and the C4 species (Tables 2 & 3). In addition, we detected significant differences in g smax among the woody plants, forbs, and graminoids (Table 3). The mean respiration rate (Mean R) varied from 0.51±0.06 to 2.22±0.17 μmol m-2 s-1 (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the mean R among the functional groups, and it did not differ between the C3 and the C4 species either (Table 3). The mean ratio of the leaf intercellular air space to the ambient CO2 concentration (Mean C i/C a) varied from 0.20±0.03 to 0.81±0.01 and 0.27±0.02 to 0.59±0.03 for the C3 and C4 species, respectively. The mean C i/C a in the C3 plants was significantly greater than it was in the C4 plants (Tables 2 & 3). Furthermore, no apparent differences in the Mean C i/C a were detected among the different functional types (Table 3).

δ13C of nighttime leaf-respired CO2

We observed a significant nocturnal shift of the δ13C of leaf-respired CO2 (δ13CR) in 20 of the 22 species studied, the exceptions being Chenopodium glaucum and Saussurea amara (Table 4). The leaf-respired CO2 at 8 pm was enriched in 13C compared with that at 4 am. However, the C3 and C4 plants showed no statistical significant difference in the amplitude of the nighttime variation in δ13CR (Table 3). Moreover, no significant differences in the nocturnal shift in δ13CR were detected among the plant functional types (Table 3).

Table 4. Carbon isotope composition.

The C isotope composition (‰) of leaf-respired CO2 (δ13CR), leaf soluble carbohydrates (δ13Csugar), leaf starch (δ13Cstarch) and leaf lipids (δ13Clipid) at 8 pm and 4 am, respectively. The carbon isotope composition of leaf bulk tissue (δ13Cbiomass) was measured once at 8 pm. The amplitude of the nighttime variation in δ13CR (Variation in δ13CR) was estimated as δ13CR-8pm—δ13CR-4am. Differences in the δ13CR between the samples collected at 8 pm and 4 am were assessed by One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the P values are presented.

| Species | δ13CR-8pm (‰) | δ13CR-4am (‰) | Variation in δ13CR | P | δ13Cbiomass (‰) | δ13Csugar-8pm (‰) | δ13Csugar-4am (‰) | δ13Cstarch-8pm (‰) | δ13Cstarch-4am (‰) | δ13Cipid-8pm (‰) | δ13Cipid-4am (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. chinensis | -22.7±0.17 | -24.5±0.16 | 1.8±0.15 | <0.01 | -26.6±0.21 | -27.4±0.55 | -27.9±0.23 | -24.7±0.17 | -25.3±0.38 | -29.9±0.36 | -29.3±0.47 |

| P. australis | -21.7±0.09 | -23.5±0.10 | 1.8±0.12 | <0.01 | -25.8±0.13 | -29.0±0.17 | -29.5±0.10 | -22.9±0.32 | -24.2±0.10 | -30.2±0.31 | -29.5±0.32 |

| L. bicolor | -24.9±0.13 | -26.6±0.16 | 1.7±0.26 | <0.01 | -28.5±0.09 | -30.1±0.20 | -30.9±0.30 | -29.6±0.06 | -30.0±0.10 | -30.0±0.22 | -30.5±0.25 |

| M. asiatica | -21.2±0.17 | -24.7±0.16 | 3.5±0.32 | <0.01 | -26.8±0.16 | -25.5±0.37 | -25.6±0.30 | -24.0±0.08 | -24.5±0.14 | -31.3±0.12 | -30.6±0.15 |

| P. simonii | -22.9±0.24 | -25.6±0.17 | 2.7±0.26 | <0.01 | -27.8±0.15 | -27.4±0.17 | -28.5±0.04 | -26.1±0.25 | -28.5±0.10 | -30.6±0.32 | -31.8±0.33 |

| P. salicina | -22.6±0.15 | -25.5±0.22 | 3.0±0.31 | <0.01 | -26.9±0.18 | -25.9±0.26 | -25.6±0.08 | -25.9±0.21 | -25.6±0.16 | -30.5±0.13 | -29.9±0.17 |

| C. glaucum | -26.0±0.32 | -26.1±0.28 | 0.2±0.47 | 0.72 | -28.5±0.18 | -32.6±0.36 | -33.3±0.26 | -26.6±0.39 | -25.4±0.36 | -30.9±0.25 | -30.3±0.15 |

| G. max | -22.6±0.16 | -24.7±0.10 | 2.2±0.25 | <0.01 | -27.8±0.07 | -28.6±0.35 | -28.5±0.35 | -26.8±0.12 | -27.7±0.10 | -32.4±0.24 | -32.2±0.25 |

| H. annuus | -26.3±0.31 | -28.1±0.26 | 1.9±0.73 | <0.01 | -28.2±0.36 | -27.7±0.26 | -26.8±0.18 | -27.0±0.25 | -27.6±0.11 | -32.3±0.42 | -32.1±0.16 |

| S. amara | -25.5±0.16 | -25.0±0.30 | 0.5±0.32 | 0.17 | -28.4±0.12 | -29.1±0.05 | -29.4±0.06 | -27.0±0.12 | -26.8±0.23 | -31.4±0.09 | -31.8±0.23 |

| V. radiata | -19.9±0.19 | -23.4±0.07 | 3.5±0.24 | <0.01 | -26.5±0.09 | -27.5±0.04 | -27.6±0.15 | -26.4±0.07 | -26.7±0.11 | -33.0±0.32 | -30.6±1.06 |

| V. unguiculata | -23.5±0.32 | -27.0±0.41 | 3.5±0.41 | <0.01 | -29.3±0.22 | -29.3±0.60 | -28.1±0.23 | -27.4±0.18 | -28.8±0.21 | -31.1±0.16 | -30.8±0.24 |

| X. sibiricum | -23.7±0.22 | -24.6±0.26 | 1.0±0.41 | 0.02 | -26.2±0.27 | -25.5±0.14 | -25.3±0.29 | -24.9±0.29 | -24.4±0.26 | -29.5±0.20 | -29.1±0.20 |

| C. virgata | -8.3±0.17 | -10.2±0.10 | 2.0±0.16 | <0.01 | -12.8±0.26 | -15.5±0.24 | -15.6±0.32 | -11.8±0.07 | -12.1±0.38 | -21.7±0.28 | -21.9±0.36 |

| E. crusgalli | -9.6±0.12 | -11.3±0.08 | 1.8±0.18 | <0.01 | -13.2±0.35 | -15.7±0.28 | -14.1±0.36 | -11.6±0.41 | -11.2±0.13 | -20.1±0.34 | -17.9±0.70 |

| H. altissima | -9.4±0.10 | -11.4±0.14 | 2.0±0.21 | <0.01 | -12.8±0.31 | -15.3±0.27 | -15.0±0.21 | -11.7±0.16 | -12.2±0.13 | -21.3±0.18 | -21.3±0.28 |

| P. miliaceum | -8.9±0.33 | -13.1±0.14 | 4.1±0.33 | <0.01 | -13.3±0.13 | -16.0±0.46 | -18.1±0.58 | -11.4±0.12 | -11.9±0.13 | -21.3±0.16 | -21.1±0.61 |

| S. italica | -8.6±0.19 | -11.9±0.30 | 3.2±0.39 | <0.01 | -12.1±0.14 | -17.7±0.16 | -16.9±0.46 | -11.2±0.21 | -11.1±0.13 | -22.2±0.51 | -20.8±0.39 |

| S. viridis | -7.3±0.14 | -9.5±0.17 | 2.2±0.27 | <0.01 | -12.2±0.07 | -13.5±0.19 | -19.4±0.24 | -11.4±0.04 | -11.8±0.29 | -21.1±0.52 | -20.5±0.64 |

| S. bicolor | -9.5±0.13 | -12.2±0.20 | 2.7±0.18 | <0.01 | -12.3±0.19 | -13.2±0.20 | -12.9±0.32 | -10.8±0.19 | -11.5±0.59 | -22.0±0.24 | -21.2±0.40 |

| Z. mays | -5.3±0.22 | -11.1±0.28 | 5.8±0.24 | <0.01 | -12.4±0.19 | -14.9±0.71 | -13.6±0.28 | -10.3±0.09 | -11.0±0.44 | -22.0±0.68 | -21.9±0.35 |

| A. retroflexus | -7.6±0.26 | -12.3±0.31 | 4.7±0.36 | <0.01 | -12.2±0.13 | -16.6±0.74 | -16.5±0.58 | -10.8±0.45 | -12.4±0.39 | -21.0±0.50 | -20.9±0.45 |

Data are reported as the mean ±1 SE (n = 5)

Correlations between the nocturnal shift in δ13CR and cumulative carbon assimilation

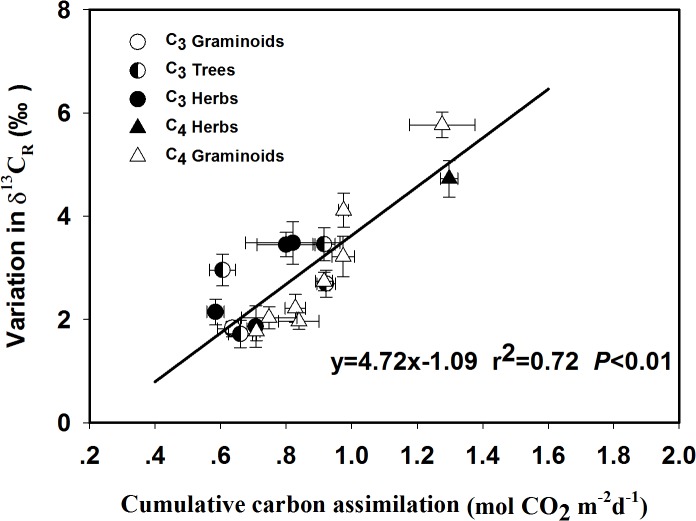

We calculated the daytime cumulative carbon assimilation, using gas-exchange data to explore the potential effects of the pool size of the daytime cumulative photosynthates on the magnitude of the nighttime variation in δ13CR. A strong positive correlation was found between the amplitude of the nighttime variation in δ13CR and the cumulative carbon assimilation (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Dependence of the amplitude of the variations in δ13C of leaf-respired CO2 (δ13CR, ‰) on the amount of cumulative carbon assimilation (mol CO2 m-2 d-1).

The data contains 19 of the 22 studied species, the exceptions being Chenopodium glaucum, Saussurea amara and Xanthium sibiricum. The r 2 and P values are provided. The data are reported as mean ±1 standard error (n = 5).

Respiratory apparent 13C/12C fractionation

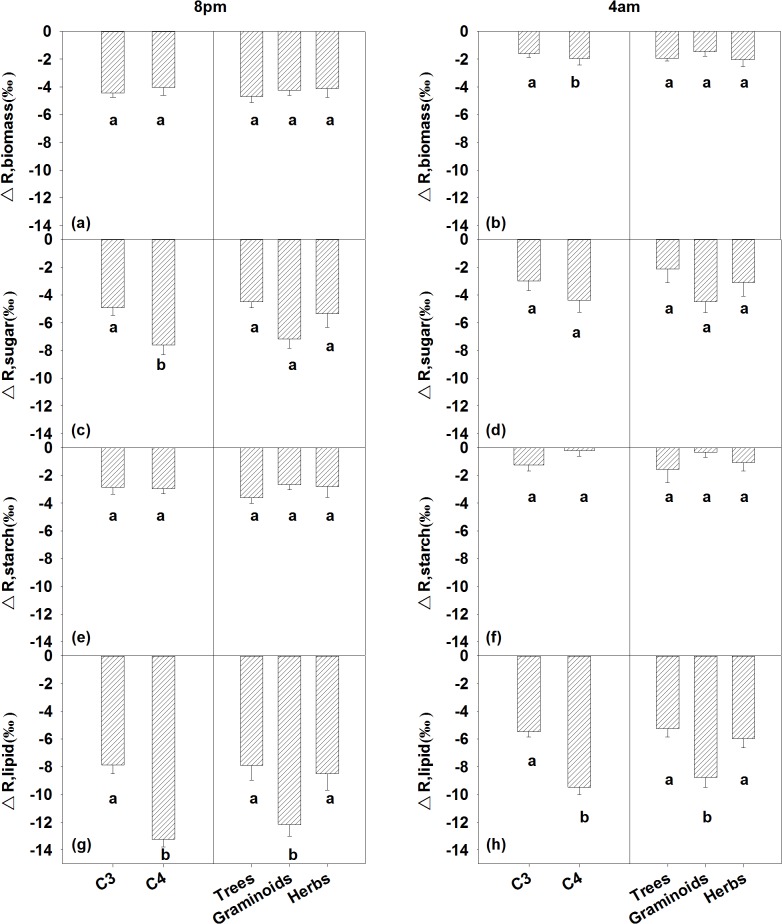

We calculated respiratory apparent 13C/12C fractionation (ΔR) relative to the δ13C values of the bulk leaf material, soluble carbohydrates (ΔR, sugar), starch (ΔR, starch), and lipids (ΔR, lipid) at 8 pm and 4 am, respectively (Table 5). Differences in ΔR, biomass between the C3 and the C4 species were detected at 4 am, but not at 8 pm (Table 3; Fig 3A and 3B). There were no nighttime ΔR, biomass differences among the trees, graminoids and herbs at either 8 pm or 4 am (Table 3; Fig 3A and 3B). Significant differences were found in the ΔR, sugar between the C3 and the C4 species at 8 pm (Table 3). Neither photosynthetic pathway nor plant functional type differences in ΔR, starch were detected (Table 3). The C3 and C4 plants differed significantly in the ΔR, lipid at both 8 pm and 4 am (Table 3; Fig 3G and 3H). We also detected plant functional type differences in the ΔR, lipid (Table 3), with the ΔR, lipid values in the graminoids being more negative than they were in the trees or herbs (Fig 3G and 3H).

Table 5. Respiratory apparent fractionation.

Respiratory apparent 13C/12C fractionation (‰) of the nighttime leaf-respired CO2, comparative to biomass (ΔR, biomass), soluble carbohydrates (ΔR, sugar), starch (ΔR, starch) and lipids (ΔR, lipid) at 8 pm and 4 am, respectively.

| Species | ΔR, biomass-8pm (‰) | ΔR, biomass-4am (‰) | ΔR, sugar-8pm (‰) | ΔR,sugar-4am (‰) | ΔR, starch-8pm (‰) | ΔR,starch-4am (‰) | ΔR, lipid-8pm (‰) | ΔR,lipid-4am (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. chinensis | -4.00±0.28 | -2.12±0.27 | -4.80±0.69 | -3.52±0.28 | -2.07±0.48 | -0.77±0.52 | -7.36±0.51 | -4.93±0.60 |

| P. australis | -4.23±0.63 | -2.35±0.23 | -7.49±0.20 | -6.10±0.12 | -1.31±0.33 | -0.68±0.16 | -8.72±0.34 | -6.19±0.31 |

| L. bicolor | -3.67±0.31 | -1.91±0.26 | -5.49±0.21 | -4.40±0.43 | -4.81±0.15 | -3.37±0.21 | -5.22±0.27 | -4.00±0.34 |

| M. asiatica | -5.72±0.33 | -2.19±0.29 | -4.42±0.32 | -0.97±0.22 | -2.90±0.16 | 0.19±0.23 | -10.35±0.20 | -6.13±0.13 |

| P. simonii | -5.02±0.43 | -2.67±0.33 | -4.62±0.39 | -3.05±0.18 | -3.27±0.40 | -3.02±0.25 | -7.90±0.55 | -6.41±0.29 |

| P. salicina | -4.41±0.41 | -1.38±0.33 | -3.40±0.40 | -0.07±0.20 | -3.46±0.34 | -0.05±0.27 | -8.15±0.27 | -4.51±0.12 |

| C. glaucum | -2.60±0.83 | -2.44±0.44 | -6.86±0.61 | -7.41±0.45 | -0.70±0.43 | 0.70±0.37 | -5.11±0.45 | -4.33±0.40 |

| G. max | -5.35±0.57 | -3.16±0.33 | -6.14±0.34 | -3.85±0.36 | -4.28±0.11 | -3.08±0.15 | -10.06±0.24 | -7.65±0.30 |

| H. annuus | -1.99±0.57 | -0.08±0.48 | -1.49±-0.86 | -1.35±0.27 | -0.77±0.41 | 0.55±0.35 | -6.21±0.59 | -4.06±0.11 |

| S. amara | -3.03±0.52 | -3.56±0.96 | -3.71±0.14 | -4.50±0.32 | -1.54±0.23 | -1.86±0.10 | -6.05±0.20 | -7.03±0.41 |

| V. radiata | -6.73±1.03 | -3.22±0.52 | -7.76±0.20 | -4.31±0.11 | -6.75±0.29 | -3.36±0.13 | -13.3±0.51 | -7.39±1.08 |

| V. unguiculata | -5.90±0.23 | -2.34±0.45 | -5.93±0.70 | -1.09±0.56 | -3.99±0.26 | -1.84±0.59 | -7.74±0.26 | -3.92±0.55 |

| X. sibiricum | -2.60±0.36 | -1.62±0.45 | -1.92±0.28 | -0.73±0.44 | -1.25±0.98 | 0.24±0.37 | -5.98±0.39 | -4.65±0.36 |

| C. virgata | -4.42±0.26 | -2.47±0.29 | -7.21±0.19 | -5.32±0.35 | -3.49±0.11 | -1.78±0.38 | -13.49±0.20 | -11.70±0.35 |

| E. crusgalli | -3.68±0.38 | -1.89±0.50 | -6.21±0.28 | -2.78±0.34 | -2.02±0.38 | 0.12±0.06 | -10.6±0.33 | -6.68±0.68 |

| H. altissima | -3.44±0.32 | -1.39±0.35 | -5.94±0.30 | -3.58±0.31 | -2.31±0.20 | -0.72±0.16 | -11.97±0.18 | -9.93±0.23 |

| P. miliaceum | -4.37±0.49 | -0.22±0.30 | -7.13±0.41 | -5.12±0.65 | -2.46±0.34 | 1.19±0.21 | -12.48±0.26 | -8.20±0.74 |

| S. italica | -3.49±0.87 | -0.24±0.39 | -8.92±0.49 | -5.09±0.64 | -2.59±0.23 | 0.74±0.34 | -13.64±0.38 | -9.02±0.45 |

| S. viridis | -4.91±0.20 | -2.68±0.19 | -10.46±0.21 | -9.99±0.19 | -4.14±0.12 | -2.30±0.18 | -13.91±0.50 | -11.09±0.59 |

| S. bicolor | -2.81±0.55 | -0.04±0.67 | -4.00±0.25 | -0.71±0.34 | -1.30±0.29 | 0.74±0.43 | -12.6±0.22 | -9.11±0.38 |

| Z. mays | -7.07±0.61 | -1.28±0.38 | -9.58±0.75 | -2.56±0.40 | -4.97±0.14 | 0.11±0.66 | -16.8±0.80 | -10.88±0.34 |

| A. retroflexus | -4.72±0.40 | -0.04±0.54 | -9.07±0.95 | -4.31±0.40 | -3.24±0.58 | -0.08±0.51 | -13.53±0.65 | -8.69±0.56 |

Fig 3. Plant functional type differences in respiratory apparent fractionation comparative to leaf bulk materials (ΔR, biomass), soluble carbohydrates (ΔR, sugar), starch (ΔR, starch) and lipids (ΔR, lipid) at 8 pm and 4 am, respectively.

Data are reported as mean ± 1 standard error (n = 5). The different letters within each panel indicate the significant differences (P <0.05) among the plant functional types.

Discussion

Variation in δ13C of leaf-respired CO2

For most of the species studied, leaf-respired CO2 collected at 8 pm and 4 am differed significant in its carbon isotope composition, with the leaf-respired CO2 at 8 pm was enriched in 13C compared with the evolved CO2 at 4 am (Table 4). This result is consistent with the findings of previous studies [12, 18, 30]. No significant variation in δ13CR were detected in two C3 herbs (Chenopodium glaucum and Saussurea amara), which is in agreement with the finding of Priault et al. (2009). However, we observed a significant variation in δ13CR in the other three herbs (Table 4) with the magnitude of the nighttime shift was up to 4.7±0.4‰ in a C4 herb Amaranthus retroflexus. In contrast with the results of Priault et al. (2009), the three tree species we studied showed significant nocturnal shifts in δ13CR. Large nocturnal shifts in δ13CR have also been reported in other tree species, such as Prosopis velutina and Celtis reticulata [25]. To assess potential plant functional type differences in the magnitude of variation in δ13CR, we grouped the studied species with significant variation in δ13CR according to their differences in photosynthetic pathway and growth form. However, there were no differences in the magnitude of variation in δ13CR between the C3 and C4 plants, as well as among the woody plants, herbs and graminoids (Table 3).

The amplitude of the nighttime variation in δ13CR was strongly correlated with the daytime cumulative carbon assimilation (Fig 2). Similar phenomenon has also been reported previously and was mainly attributed to changes in the contribution of light-enhanced dark respiration (LEDR) associated malate decarboxylation to the total respiratory CO2 flux [8, 14]. In the light, malate, fixed by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPc), accumulates because of the inhibition of the key respiratory enzymes, such as the mitochondrial isocitrate dehydrogenase, the succinate dehydrogenase, and the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase [16, 37]. In darkness, the mitochondrial malic enzyme and the mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase catalyzed decarboxylation of the 13C-enriched malate pool caused the respired CO2 to be 13C enriched [38]. In a study by Barbour et al. (2011), they reported the effects of LEDR associated malate decarboxylation on 13C-enrichment in leaf-respired CO2 can last up to 100 min after sunset. For the present study, 13C enrichment in leaf-respired CO2 at 8 pm (40–50 min after sunset) may partially be attributed to the decarboxylation of malate.

Large diel variation in photosynthetic discrimination (ΔP) has also been hypothesized to affect δ13CR by changing the δ13C of the primary respiratory substrates [18, 28]. We observed no significant differences in the primary respiratory sources (soluble carbohydrates, starch, and lipids) between 8 pm and 4 am. A previous report [24] has also found no apparent variation in the δ13C of the leaf primary respiratory substrates. However, we could not discount the effects of the changes in the use of respiratory substrates having different δ13C, because we, along with most other studies, measured the δ13C of the entire leaf respiratory substrate pools. It is difficult to identify the pool size and the isotopic signature of the fast- and the slow-turnover pools.

Other mechanisms, such as heterogeneous 13C distribution within hexose molecules and nighttime variation in the utilization of respiratory intermediates [14, 21], short term variation in carbohydrate pool size and respiration rate, have also been employed to explain nighttime variation in δ13CR [15, 16]. However, with the current data set we are unable to test these hypotheses.

Respiratory apparent 13C/12C fractionation

Leaf-respired CO2 was enriched in 13C compared with the biomass, starch, soluble carbohydrates, and lipids (Table 5). This finding is in agreement with the results of previous studies [16, 19, 27, 28, 39, 40]. 13C enrichment in leaf-respired CO2, relative to the potential respiratory substrates, could be caused by the incomplete oxidation of hexose molecules, which cause a greater ratio of C-3 and C-4 atoms (13C enriched compared with other C atoms) being converted to CO2 [30, 37]. However, there were some differences in the magnitude of the respiratory apparent fractionation between the C3 and C4 species, and among the different plant functional types (Fig 3, Table 3). Differences in ΔR, biomass were detected between C3 and C4 species at 4 am, but not at 8 pm, which were caused primarily by different magnitude of variation in δ13CR between the two photosynthetic types. In a recent review paper, Ghashghaie & Badeck (2014) reported that C3 and C4 species differed in ΔR, biomass. There were no differences in the ΔR, biomass among the trees, the herbs, and the graminoids (Fig 3A), which is in line with the results of Ghashghaie & Badeck (2014). The detected differences in ΔR, biomass between C3 and C4 species needs to be incorporated into the partitioning of the CO2 exchange between the ecosystem and the atmosphere when leaf bulk materials are used as a proxy for δ13CR [25].

ΔR, lipid significantly differed between the C3 and the C4 plants, as well as among the plant functional types (Table 3), which could have resulted primarily from the carbon allocation differences associated with the plant functional group types. Compared with the woody plants or the herbs, the grasses allocated a smaller proportion of acetyl CoA to the synthesis of lipids. This leads to grass lipids being generally more depleted compared with the bulk tissue [26, 41].

Soluble carbohydrates are often found to be 13C-enriched compared to bulk leaf material [9, 15, 28]. However, we observed that soluble carbohydrates in 16 of the 22 studied species were depleted in 13C relative to the leaf biomass (Table 4). Similar results with up to 4‰ depletion in soluble carbohydrates compared to bulk materials have also been reported previously in various C3 and C4 species [3535, 36, 42]. This discrepancy may be attributed to both differences in the extraction method and timing of leaf sample collection.

Conclusions

For both the C3 and the C4 species (except Chenopodium glaucum and Saussurea amara), the δ13C of leaf-respired CO2 (δ13CR) showed a significant nocturnal shift. The leaf-respired CO2 at 8 pm was enriched in 13C, relative to what it was at 4 am. The amplitude of the nighttime variation in δ13CR was strongly correlated with the daytime cumulative carbon assimilation, which suggests that variation in δ13CR were influenced, to some extent, by changes in the contribution of malate decarboxylation to total respiratory CO2 flux. There were no differences in the magnitude of the nocturnal shift in δ13CR between the C3 and C4 plants, as well as among the woody plants, herbs and graminoids. The plant functional group differences in respiratory apparent fractionation relative to biomass indicate that caution should be exercised when the δ13C of bulk leaf material is used as a proxy for the δ13C of leaf-respired CO2.

Acknowledgments

Chunge Liu is thanked for assistance with the collection of leaf-respired CO2. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31270445), the State Key Laboratory of Vegetation and Environmental Change (LVEC2012kf01), and the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-12-0814).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31270445), the State Key Laboratory of Vegetation and Environmental Change (LVEC2012kf01), and Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-12-0814). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Schnyder H, Lattanzi FA. Partitioning respiration of C3-C4 mixed communities using the natural abundance 13C approach—Testing assumptions on a controlled environment. Plant Biology. 2005;7(6):592–600. 10.1055/s-2005-872872 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shimoda S, Murayama S, Mo W, Oikawa T. Seasonal contribution of C3 and C4 species to ecosystem respiration and photosynthesis estimated from isotopic measurements of atmospheric CO2 at a grassland in Japan. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 2009;149:603–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Griffis TJ, Baker JM, Zhang J. Seasonal dynamics and partitioning of isotopic CO2 exchange in a C3/C4 managed ecosystem. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 2005;132(1–2):1–19. 10.1016/j.agrformet.2005.06.005 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lloyd J, Kruijt B, Hollinger DY, Grace J, Francey RJ, Wong SC, et al. Vegetation effects on the isotopic composition of atmospheric CO2 at local and regional scales: Theoretical aspects and a comparison between rain forest in Amazonia and a boreal forest in Siberia. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 1996;23(3):371–99. . [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowling DR, Tans PP, Monson RK. Partitioning net ecosystem carbon exchange with isotopic fluxes of CO2 . Global Change Biology. 2001;7:127–45. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scartazza A, Mata C, Matteucci G, Yakir D, Moscatello S, Brugnoli E. Comparisons of δ13C of photosynthetic products and ecosystem respiratory CO2 and their response to seasonal climate variability. Oecologia. 2004;140(2):340–51. 10.1007/s00442-004-1588-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Knohl A, Buchmann N. Partitioning the net CO2 flux of a deciduous forest into respiration and assimilation using stable carbon isotopes. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 2005;19(4):GB4008 10.1029/2004gb002301|issn 0886–6236. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barbour MM, Hunt JE, Kodama N, Laubach J, McSeveny TM, Rogers GND, et al. Rapid changes in δ13C of ecosystem-respired CO2 after sunset are consistent with transient 13C enrichment of leaf respired CO2 . New Phytologist. 2011;190:990–1002. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03635.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bowling DR, Pataki DE, Randerson JT. Carbon isotopes in terrestrial ecosystem pools and CO2 fluxes. New Phytologist. 2008;178(1):24–40. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02342.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Werner C, Schnyder H, Cuntz M, Keitel C, Zeeman MJ, Dawson TE, et al. Progress and challenges in using stable isotopes to trace plant carbon and water relations across scales. Biogeosciences. 2012;9:3083–111. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Werner C, Hasenbein N, Maia R, Beyschlag W, Maguas C. Evaluating high time-resolved changes in carbon isotope ratio of respired CO2 by a rapid in-tube incubation technique. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2007;21:1352–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hymus GJ, Maseyk K, Valentini R, Yakir D. Large daily variation in 13C-enrichment of leaf-respired CO2 in two Quercus forest canopies. New Phytologist. 2005;167:377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prater JL, Mortazavi B, Chanton JP. Diurnal variation of the δ13C of pine needle respired CO2 evolved in darkness. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2006;29:202–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Priault P, Wegener F, Werner C. Pronounced differences in diurnal variation of carbon isotope composition of leaf respired CO2 among functional groups. New Phytologist. 2009;181:400–12. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02665.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ghashghaie J, Badeck FW. Opposite carbon isotope discrimination during dark respiration in leaves versus roots—a review. New Phytologist. 2014;201:751–69. 10.1111/nph.12563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Werner C, Gessler A. Diel variations in the carbon isotope composition of respired CO2 and associated carbon sources: a review of dynamics and mechanisms. Biogeosciences. 2011;8(9):2437–59. 10.5194/bg-8-2437-2011 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Werner C, Wegener F, Unger S, Nogues S, Priault P. Short-term dynamics of isotopic composition of leaf-respired CO2 upon darkening: measurements and implications. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2009;23:2428–38. 10.1002/rcm.4036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sun W, Resco V, Williams DG . Diurnal and seasonal variation in the carbon isotope composition of leaf dark-respired CO2 in velvet mesquite (Prosopis velutina). Plant, Cell and Environment. 2009;32:1390–400. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghashghaie J, Badeck F-W, Lanigan G, Nogués S, Tcherkez G, Deléens E, et al. Carbon isotope fractionation during dark respiration and photorespiration in C3 plants. Phytochemistry Review. 2003;2:145–61. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Badeck F-W, Tcherkez G, Nogués S, Piel C, Ghashghaie J. Post-photosynthetic fractionation of stable carbon isotopes between plant organs—a widespread phenomenon. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2005;19(11):1381–91. 10.1002/rcm.1912 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rossmann A, Butzenlechner M, Schmidt H-L. Evidence for a nonstatistical carbon isotope distribution in natural glucose. Plant Physiology. 1991;96:609–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wegener F, Beyschlag W, Werner C. The magnitude of diurnal variation in carbon isotopic composition of leaf dark respired CO2 correlates with the difference between δ13C of leaf and root material. Functional Plant Biology. 2010;37:849–58. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barbour MM, McDowell NG, Tcherkez G, Bickford CP, Hanson DT. A new measurement technique reveals rapid post-illumination changes in the carbon isotope composition of leaf-respired CO2 . Plant Cell and Environment. 2007;30(4):469–82. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01634.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun W, Resco V, Williams DG. Environmental and physiological controls on the carbon isotope composition of CO2 respired by leaves and roots of a C3 woody legume (Prosopis velutina) and a C4 perennial grass (Sporobolus wrightii). Plant, Cell and Environment. 2012;35:567–77. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02436.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sun W, Resco V, Williams DG. Nocturnal and seasonal patterns of carbon isotope composition of leaf dark-respired carbon dioxide differ among dominant species in a semiarid savanna. Oecologia. 2010;164:297–310. 10.1007/s00442-010-1643-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hobbie EA, Werner RA. Intramolecular, compound-specific, and bulk carbon isotope patterns in C3 and C4 plants: a review and synthesis. New Phytologist. 2004;161:371–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Duranceau M, Ghashghaie J, Badeck F, Deleens E, Cornic G. δ13C of CO2 respired in the dark in relation to δ13C of leaf carbohydrates in Phaseolus vulgaris L. under progressive drought. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1999;22:515–23. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ghashghaie J, Duranceau M, Badeck F-W, Cornic G, Adeline M-T, Deleens E. δ13C of CO2 respired in the dark in relation to δ13C of leaf metabolites: comparison between Nicotiana sylvestris and Helianthus annuus under drought. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2001;24:505–15. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xu C-Y, Lin G-H, Griffin KL, Sambrotto RN. Leaf respiratory CO2 is 13C-enriched relative to leaf organic components in five species of C3 plants. New Phytologist. 2004;163:499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tcherkez G, Nogues S, Bleton J, Cornic G, Badeck F, Ghashghaie J. Metabolic origin of carbon isotope composition of leaf dark-respired CO2 in French bean. Plant Physiology. 2003;131(1):237–44. 10.1104/pp.013078 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Melzer E, Oleary MH. Anapleurotic CO2 fixation by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase in C3 plants. Plant Physiology. 1987;84(1):58–60. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Melzer E, Schmidt H-L. Carbon isotope effects on the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction and their importance for relative carbon-13 depletion in lipids. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262(17):8159–64. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jiang L, Guo R, Zhu TC, Niu XD, Guo JX, Sun W. Water- and plant-mediated responses of ecosystem carbon fluxes to warming and nitrogen addition on the Songnen grassland in Northeast China. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e45205 10.1371/journal.pone.0045205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang YB, Jiang Q, Yang ZM, Sun W, Wang DL. Effects of water and nitrogen addition on ecosystem carbon exchange in a meadow steppe. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0127695 10.1371/journal.pone.0127695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wanek W, Heintel S, Richter A. Preparation of starch and other carbon fractions from higher plant leaves for stable carbon isotope analysis. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2001;15(14):1136–40. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Göttlicher S, Knohl A, Wanek W, Buchmann N, Richter A. Short-term changes in carbon isotope composition of soluble carbohydrates and starch: from canopy leaves to the root system. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2006;20:653–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gessler A, Tcherkez G, Karyanto O, Keitel C, Ferrio JP, Ghashghaie J, et al. On the metabolic origin of the carbon isotope composition of CO2 evolved from darkened light-acclimated leaves in Ricinus communis . New Phytologist. 2009;181:374–86. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Werner RA, Buchmann N, Siegwolf RTW, Kornexl BE, Gessler A. Metabolic fluxes, carbon isotope fractionation and respiration—lessons to be learned from plant biochemistry. New Phytologist. 2011;191(1):10–5. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03741.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Duranceau M, Ghashghaie J, Brugnoli E. Carbon isotope discrimination during photosynthesis and dark respiration in intact leaves of Nicotiana sylvestris: comparisons between wild type and mitochondrial mutant plants. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 2001;28:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ocheltree TW, Marshall JD. Apparent respiratory discrimination is correlated with growth rate in the shoot apex of sunflower (Helianthus annuus). Journal of Experimental Botany. 2004;55(408):2599–605. 10.1093/jxb/erh263|ISSN 0022-0957. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Park R, Epstein S. Metabolic fractionation of 13C and 12C in plants. Plant Physiology. 1961;36:133–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wingate L, Ogée J, Burlett R, Bosc A, Devaux M, Grace J, et al. Photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination and its relationship to the carbon isotope signals of stem, soil and ecosystem respiration. New Phytologist. 2010;188:576–89. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03384.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.