Abstract

The purpose of the study was to identify groups of adolescents based on their reported use of different coping strategies and compare levels of depression and anxiety symptoms across the groups. Tenth and eleventh grade public school students (N = 982; 51% girls; 66% Caucasian; M age =16.04, SD = .73) completed a battery of self-report measures that assessed their use of different coping strategies, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms. Latent profile analysis (LPA) classified the participants into four distinct groups based on their responses on subscales of the COPE inventory (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989). Groups differed in amount of coping with participants in each group showing relative preference for engaging in certain strategies over others. Disengaged copers reported the lowest amounts of coping with a preference for avoidance strategies. Independent copers reported moderate levels of coping with relatively less use of support-seeking. Social support-seeking copers and active copers reported the highest levels of coping with a particular preference for support-seeking strategies. The independent copers reported the lowest levels of depressive symptoms compared to the three other groups. The Social Support Seeking and Active Coping Groups reported the highest levels of anxiety. Although distinct coping profiles were observed, findings showed that adolescents between the ages of 14 and 16 engage in multiple coping strategies and are more likely to vary in their amount of coping than in their use of specific strategies.

Keywords: adolescent coping, internalizing symptoms, latent profile analysis

Coping refers to the ways in which individuals respond to and manage stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). In line with the diathesis-stress model of depression, individual differences in coping have been used to differentiate people who develop depressive symptoms following stressful events from those who experience stress but do not develop depressive symptoms (Compas, Orosan, & Grant, 1993; Evans et al., 2015; Ingram & Luxton, 2005; Sawyer, Pfeiffer, & Spence, 2009). Thus, coping can serve as a protective factor against the potentially harmful consequences of stress. Coping evolves over the course of development as individuals learn new strategies and refine old strategies (Amirkhan & Auyeung, 2007). Certain types of coping strategies are more effective than others in adaptively responding to stress during adolescence (Griffith, Dubow, & Ippolito, 2000). Ineffective or maladaptive coping strategies are linked with poor adolescent adjustment, including the development of internalizing problems (Compas et al., 2001). However, individuals do not engage in only one type of coping, and, thus, reliance on single strategies to differentiate risk for psychopathology does not account for the complexity of adolescent coping and its consequences. Rather, identifying typologies of adolescents who employ similar patterns of coping may provide a better understanding of how adolescent coping affects adjustment (Aldridge & Roesch, 2008).

Approach versus Avoidant Coping

Coping strategies have been categorized conceptually into approach and avoidance strategies (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010; Litman, 2006; Roth & Cohen, 1986). Approach strategies, also referred to as engagement strategies or problem-focused strategies, include primary control (e.g., problem solving) and secondary control (e.g., cognitive restructuring) strategies utilized in an attempt to alter the stressfulness of a situation. Seeking emotional support from others also is typically classified as an approach strategy in that it is active and emotionally constructive (Skinner, Edge, Altman, & Sherwood, 2003). Avoidance strategies (i.e., disengagement/emotion focused strategies) include attempts to ignore or deny the existence of a stressor. Avoidance strategies may relieve short-term distress associated with stress. However, these types of strategies increase the intensity and frequency of distress in the long term and lead to the development of problem behaviors (Lynch, Robins, Morse, & Morkrause, 2001). There is substantial evidence that approach coping is related to positive health outcomes and increased wellbeing, whereas avoidance coping is less adaptive and associated with problem behaviors, including depression (Compas et al., 2001).

In their review, Compas et al. (2001) reported that the majority of studies showed a positive relationship between avoidance coping and internalizing symptoms during adolescence, whereas approach strategies were negatively associated with internalizing symptoms. More recent studies also have shown that avoidance coping (e.g., withdrawal) predicts increases over time in adolescent symptomatology, including depressive symptoms and substance use (Cicognani, 2011; Seiffge-Krenke, 2000; Seiffge-Krenke & Klessinger, 2000; Wills, Yaeger, Cleary, & Sinar, 2001). In addition, Evans et al. (2015) found that engagement and disengagement strategies mediated the link between stress and depressive symptoms: less use of primary control engagement strategies and greater use of disengagement strategies were associated with higher depressive symptoms following the experience of stressful events. Avoidant coping strategies also have been found to mediate the link between negative events and anxiety symptoms during adolescence (Lewis, Byrd, & Ollendick, 2012). In addition, less avoidant coping is associated with better treatment gains in treatment for adolescent anxiety (Essau, Conradt, Sasgawa, & Ollendick, 2012).

Although scholars commonly dichotomize coping into broadband categories (e.g., approach vs. avoidance strategies), studies employing factor analysis suggest that categorizing coping into narrowband dimensions more adequately represents the range of youth coping behavior (Connor-Smith, Compas, Wadsworth, Thomsen, & Saltzman, 2000; Skinner et al., 2003). Given that individuals tend to engage in multiple coping strategies, the current study takes a multidimensional approach to studying adolescent coping by investigating coping profiles, rather than focusing on any single strategy. Coping profiles combine information across coping scales in order to provide information not available from any one scale. Identifying coping profiles across multiple strategies may differentiate distinct groups of adolescents who report varying levels of internalizing problems.

Coping in Adolescence

Adolescence is a critical period for studying coping (Hussong & Chassin, 2004). Numerous changes occur during this time period, including pubertal development, the development of autonomy, identity formation, and increases in cognitive, behavioral, and emotional capacities for self-regulation (Compas et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2010; Griffith et al., 2000; Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Metzger, 2006; Spear, 2000). Changes in family and peer relationships occur as well as adolescents spend increasing amounts of time with peers (Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Metzger, 2006). The school context also changes as adolescents transition to high school (Barber & Olsen, 2004; Waters, Lester, & Cross, 2014). Managing the vast number of changes during adolescence may be difficult for some youth. Thus, it is not surprising that the prevalence of psychological problems, including internalizing problems, rises dramatically during this time period (Davey, Yücel, & Allen, 2008; Essau, Conradt, & Petermann, 2000).

Adolescents may find it challenging to choose appropriate strategies for coping with the stress that accompanies these developmental changes. In general, adolescents tend to become more selective about their use of coping strategies in different contexts (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). For example, adolescents use more avoidance than approach strategies when coping with family stressors and more approach than avoidance strategies when coping with school and peer stressors (Griffith et al., 2000). Given that changes in coping coincide with increased internalizing symptoms during adolescence, particularly for girls (Bekker & van Mens-Verhulst, 2007; Ge, Lorenze, Conger, Elder, & Simons, 1994; Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005; Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994), studying relations between the use of different coping strategies and internalizing problems is particularly relevant during this time period.

Gender Differences in Coping

Research suggests that adolescent girls and boys differ in their use of coping strategies. In general, girls use a wider range of coping strategies compared to boys (Cicognani, 2011) and generally report engaging in more coping strategies (Wilson, Pritchard, & Revalee, 2005). One explanation for this gender difference is that girls experience more stressful events than boys, and thus must engage in more coping. An alternative explanation is that girls are simply more willing to report higher levels of coping than males. Typically, studies show that adolescent girls are more likely to report the use of approach strategies (e.g., Compas et al., 2001; Griffith et al., 2000), whereas boys are more likely to rely on avoidance strategies (e.g., Stark et al., 1989). For example, girls are more likely to seek social support and engage in problem solving compared to boys (Eschenbeck, Kohlmann, & Lohaus, 2007; Seiffge-Krenke, 2011; Tenenbaum, Varjas, Meyers, & Parris, 2011). The difference between boys and girls in their use of social support may reflect girls’ tendency to place a higher value on interpersonal relationships (Rudolph, 2002). The increase in stressful life events for adolescent girls and their use of different coping strategies may explain why girls are more vulnerable to depression than boys (Kessler et al., 2005).

The COPE Inventory

One common measure of coping that differentiates the use of different coping strategies is the COPE inventory, a questionnaire developed by Carver and colleagues (1989) based on theory and empirical research. In their original validation study (Carver et al., 1989), the authors used 53 items to assess different coping behaviors and identified four higher order factors (task, cognitive, emotion, and avoidance) and 13 subscales to assess distinct ways of coping (active coping, planning, suppression of competing activities, restraint coping, seeking of instrumental social support, seeking of emotional social support, positive reinterpretation, acceptance, denial, turning to religion, venting of emotions, behavioral disengagement, and mental disengagement). However, evidence of these higher order and lower order factors has not been replicated across studies (e.g., Litman, 2006), possibly due to differences in study populations. In a sample of depressed and anxious adults, Pang, Strodl, and Oei (2013) did not find support for higher order scales differentiating approach from avoidance strategies, although six lower order factors emerged (active planning, social support, denial, acceptance, disengagement, restraint).

The COPE inventory has been used to differentiate risk for psychosocial and health outcomes. Litman (2006) examined the dimensionality of the COPE scale with adult students, and found that approach-oriented subscales and avoidance-oriented subscales hung together but were not related across categories (i.e., approach-oriented scales did not correlate with avoidance-oriented scales). In addition, the approach-oriented scales positively correlated with behavioral activation and positive traits (curiosity), whereas the avoidant coping scales positively correlated with avoidance motives (behavioral inhibition) and negative traits (anxiety, depression, and anger). In another study of the COPE inventory with adults, Litman and Lunsford (2009) found that emotional venting and behavioral disengagement predicted diminishment (e.g. reduced self-esteem, greater pessimism), which in turn, predicted illness.

Factor analysis of the COPE inventory with adolescents has identified similar factors to those found with adults (e.g., active coping, avoidant coping, emotion-focused coping, and acceptance; Phelps & Jarvis, 1994). Previous research on the COPE inventory with adolescents has focused on examining associations between psychosocial problems and the use of individual coping strategies (e.g., Horwitz, Hill, & King, 2011). One exception is a study that used cluster analysis of the COPE to identify adolescent coping typologies associated with risk for adult substance use and abuse (Ohannessian, Bradley, Waninger, Ruddy, Hepp, & Hesselbrock, 2010). The Ohannesian et al. study demonstrated that adolescents use multiple coping strategies when confronted with a problem. Thus, combining information across individual coping scales rather than relying on information provided by a single scale may provide a better picture of how adolescents cope, and, in turn, may differentiate levels of problem behavior.

The Current Study

Although research comparing psychosocial problems associated with the use of individual coping strategies has identified types of strategies that are more adaptive than others, previous research has not tested whether constellations of coping strategies are associated with different levels of internalizing problems. The present study sought to address this limitation: Rather than isolating subtypes of coping to focus on single strategies, the study combined information across strategies to account for the complex, multidimensional nature of coping. Latent profile analysis was used to identify a categorical latent structure of coping that differentiated groups of adolescents who employ similar patterns of coping responses. The following research questions were examined: 1) Can a common self-report measure of adolescent coping (COPE Inventory; Carver et al., 1989) identify profiles of adolescents with a preference for certain strategies? 2) Does the composition of the different profiles vary in terms of adolescent demographic characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity, and age)? and 3) Are the different coping typologies differentially associated with levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms?

Method

Participants

All of the participating adolescents were involved in a larger research project (Ohannessian, 2009). During the spring of 2007, 10th and 11th grade students attending public high schools in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. were invited to participate in the study. The sample included 982 15–17 year-old girls (54%) and boys from seven public high schools. The mean age of the adolescents was 16.09 (SD=.68). Sixty-five percent of the youth were Caucasian, 19% were African-American, 11% were Hispanic, and 2% were Asian (the remainder described themselves as “other”). These percentages reflect the area from which the sample was drawn (71% Caucasian, 23% African American, 7% Hispanic, 4% Asian; U.S. Census Bureau, 2008).

The majority of the adolescents (60%) lived with both of their biological parents – 91% of the adolescents lived with their biological mother and 65% lived with their biological father. Most of the parents (96% of mothers and 97% of fathers) had graduated from high school. Some of the parents (35% of mothers and 32% of fathers) had completed four years of college as well. A minority of the parents (9% of mothers and 8% of fathers) had attended graduate or medical school.

Measures

The adolescents were administered a survey that included a variety of measures related to the family and adolescent psychological adjustment. The measures that are relevant to this specific study are discussed below.

Adolescent coping

The adolescents completed the 60-item COPE Inventory (Carver et al., 1989) to assess their coping strategies. The following scales were included in this study: Active coping (“I concentrate my efforts on doing something about it”; α = .75), denial (“I say to myself ‘this isn’t real’”; α = .83), emotional social support (“I discuss my feelings with someone”; α = .86), humor (“I laugh about the situation”; α = .89), instrumental social support (“I try to get advice from someone about what to do”; α = .82), mental disengagement (“I do other activities to take my mind off things”; α = .55), planning (“I make a plan of action”; α = .82), religious coping (“I put my trust in God”; α = .90), and venting emotions (“I get upset and let my emotions out”; α = .83). The response scale for the COPE items ranges from 1 = don’t do this at all to 4 = do this a lot. Previous research has shown that The COPE is psychometrically sound for use with adolescents (Phelps & Jarvis, 1994).

Adolescent depression

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC; Weissman, Orvaschell, & Padian, 1980). The CES-DC is completed in relation to how the adolescent felt or acted during the past week. A representative CES-DC item is “I felt sad.” The CES-DC response scale ranges from 1 = not at all to 4 = a lot. In the present study, the CES-DC items were summed to reflect a total depressive symptomatology score (range = 20–80). Previous research has shown that the CES-DC is a reliable and valid measure of depressive symptomatology during adolescence (Garrison, Addy, Jackson, McKeown, & Waller, 1991; Ohannessian, Lerner, Lerner, & von Eye, 1999). The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the CES-DC in our sample was .91.

Adolescent anxiety

The 41-item Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher, Khetarpal, Cully, Brent, & McKenzie, 1995) was given to the adolescents to assess their anxiety. The SCARED items are completed in reference to the last three months. A sample item is “I get really frightened for no reason at all.” The SCARED response scale ranges from 0 = not true or hardly ever true to 2 = very true or often true. In this study, the 41 SCARED items were summed to reflect a total anxiety symptomatology score (range = 0–82). Prior research has shown that the SCARED has good psychometric properties (Birmaher, Khetarpal, Cully, Brent, & McKenzie, 2003; Muris, Merckelbach, Ollendick, King, & Bogie, 2002). The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the SCARED total score in our sample was .94.

Procedures

The research protocol for the study was approved by the University of Delaware’s IRB. Public high schools in the Mid-Atlantic region (Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Maryland) were invited to take part in the study. In the spring of 2007, 10th and 11th grade students from seven high schools agreed to participate. Prior to data collection, parents were mailed a consent form describing the study, and were asked to contact the study staff via phone, e-mail, or mail if they did not want their adolescent to participate. Only two parents contacted the staff to request that their adolescent not participate. Prior to participation, the adolescents were assured that all of the data collected were confidential (an active Certificate of Confidentiality from the U.S. government was in place to further protect their privacy), participation was voluntary, and they could withdraw from the study at any time. Adolescents who agreed to participate signed an assent form prior to participation (45 adolescents declined participation). In total, 71% of the eligible students participated. The majority of that students who did not participate were students who were absent on the day of data collection. Participants were administered a self-report survey by trained research staff (all of whom were certified with human subjects training). The survey took approximately 40 minutes to complete. The adolescents were compensated for their participation with a movie pass.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations for the nine COPE scales are shown in Table 1. Overall, the adolescents were most likely to seek instrumental and emotional support as a coping strategy when faced with a stressor and least likely to engage in denial as a coping strategy. All of the COPE scales were significantly correlated with one another, with small correlations between the approach-oriented and avoidance-oriented coping scales (e.g., emotional support and denial), and large correlations among the approach-oriented scales (e.g., planning and active coping). As expected, the two forms of social support (emotional support and instrumental support) were highly correlated (r = .82, p < .05). Table 2 lists the correlations and descriptive statistics separately for girls and boys. Girls reported significantly higher mean scores than boys on the following scales: emotional social support (t (926) = 11.91, p < .01), instrumental social support (t (923) = 9.25, p < .01), active coping (t (929) = 2.40, p < .05), disengagement (t (934) = 3.69, p < .01), religious coping (t (917) = 3.26, p < .01), and venting (t (930) = 12.25, p < .01).

Table 1.

Correlations and descriptive statistics for the COPE scales.

| Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | M | SD | ||

| 1. | Active Coping | -- | 9.30 | 2.85 | |||||||

| 2. | Denial | 0.30** | -- | 6.53 | 2.80 | ||||||

| 3. | Emotional Support | 0.55** | 0.29** | -- | 9.72 | 3.46 | |||||

| 4. | Humor | 0.29** | 0.34** | 0.24** | -- | 8.95 | 3.50 | ||||

| 5. | Instrumental Support | 0.62** | 0.29** | 0.82** | 0.25** | -- | 9.70 | 3.24 | |||

| 6. | Disengagement | 0.33** | 0.41** | 0.32** | 0.42** | 0.35** | -- | 9.59 | 2.67 | ||

| 7. | Planning | 0.78** | 0.31** | 0.55** | 0.28** | 0.59** | 0.32** | -- | 9.48 | 3.14 | |

| 8. | Religion | 0.33** | 0.25** | 0.32** | 0.12** | 0.26** | 0.16** | 0.39** | -- | 8.83 | 3.96 |

| 9. | Venting | 0.35** | 0.31** | 0.62** | 0.12** | 0.55** | 0.29** | 0.31** | 0.20** | 8.73 | 3.30 |

p < .01,

p < .05

Table 2.

Correlations between the COPE scales for boys (n = 441) and girls (n = 509) and descriptive statistics.

| Boys | Girls | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| 1. | Active Coping | -- | .38** | .59** | .34** | .69** | .36** | .78** | .32** | .39** | 9.06 | 2.86 | 9.51 | 2.82 |

| 2. | Denial | .23** | -- | .43** | .31** | .38** | .44** | .39** | .35** | .48** | 6.39 | 2.74 | 6.66 | 2.85 |

| 3. | Emotional Support | .54** | .18** | -- | .34** | .79** | .36** | .63** | .44** | .58** | 8.36 | 3.17 | 10.89 | 3.27 |

| 4. | Humor | .26** | .37** | .24** | -- | .31** | .43** | .34** | .12* | .21** | 9.19 | 3.46 | 8.76 | 3.53 |

| 5. | Instrumental Support | .57** | .22** | .82** | .25** | -- | .39** | .66** | .32** | .53** | 8.69 | 3.10 | 10.58 | 3.10 |

| 6. | Disengagement | .30** | .38** | .26** | .42** | .28** | -- | .36** | .18** | .34** | 9.25 | 2.72 | 9.89 | 2.59 |

| 7. | Planning | .78** | .24** | .53** | .24** | .56** | .28** | -- | .37** | .36** | 9.39 | 3.15 | 9.55 | 3.14 |

| 8. | Religion | .32** | .17** | .20** | .13** | .19** | .12* | .41** | -- | .29** | 8.38 | 3.69 | 9.23 | 4.13 |

| 9. | Venting | .32** | .19** | .54** | .12** | .47** | .21** | .30** | .10* | -- | 7.40 | 2.90 | 9.87 | 3.20 |

Note. Correlations for boys and girls are displayed above and below the diagonal, respectively.

p < .01,

p < .05

Latent Profile Analysis

Latent profile analysis (LPA) conducted using Mplus Version 6.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010) identified distinct groups that accounted for the distribution of subjects across the nine COPE scales. The default estimation technique for LPA in MPLUS is maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR), a technique that is robust to violations of normality (Yuan & Bentler, 2000). LPA models with increasing numbers of groups were fitted to the data until comparative fit statistics suggested that the estimated model did not provide statistically significant improvement in fit over a model with one fewer group. Fit statistics for models in which one to five groups were fitted to the data are presented in Table 3. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and the Sample-Size-Adjusted BIC were used to estimate model fit; lower numbers represent better-fitting models (Kline, 2005). The Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test and the adjusted Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test were used to compare models. Finally, the Entropy measure was used to indicate how well the models classified individuals into groups; values of Entropy range from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 suggesting better classification of individuals to groups (Kline, 2005). Although the five group model had a lower BIC and a lower Adjusted BIC than the four group model, both likelihood ratio tests supported a four-group model; p values indicated that the five group model did not fit the data better than the four group model. Moreover, entropy for the four-group model suggested good classification qualities.

Table 3.

Fit statistics for LPA models representing one to five Coping Groups.

| # of Groups |

BIC | SSA BIC | VLMR | p-value | Adj. LMR |

p-value | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43152.82 | 43095.65 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 2 | 41279.35 | 41190.42 | −21514.70 | 0.00 | 1914.12 | 0.00 | 0.85 |

| 3 | 40726.84 | 40606.15 | −20543.68 | 0.00 | 612.15 | 0.00 | 0.84 |

| 4 | 40460.75 | 40308.30 | −20233.15 | 0.01 | 329.84 | 0.01 | 0.84 |

| 5 | 40314.72 | 40130.52 | −20065.82 | 0.25 | 211.50 | 0.25 | 0.85 |

Note. BIC, Bayesian Information Criterion; SSA BIC, Sample-Size-Adjusted BIC; VLMR, Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test; Adj. LMR, Adjusted Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test; n/a, not applicable

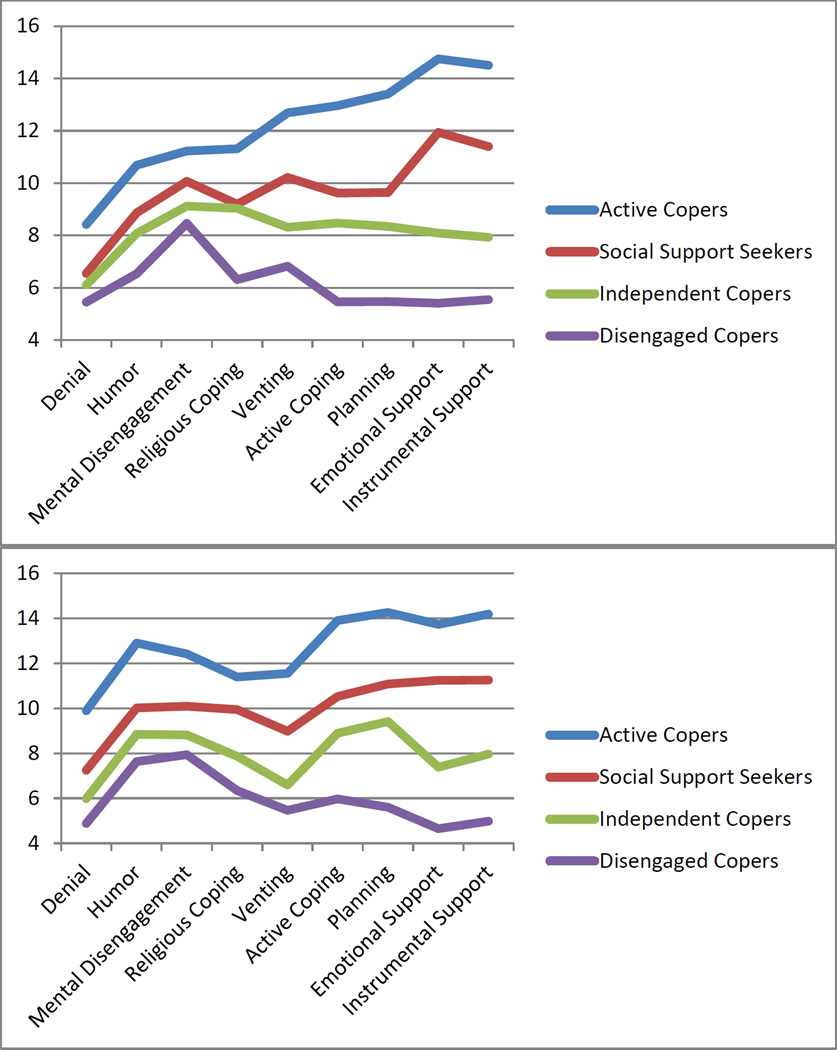

Table 4 lists means and standard deviations (SD) for the Cope scales across the four groups (see also Figure 1). Analyses of variance (ANOVA) showed significant overall differences in means for the group indicators (the F statistic is reported in Table 4). Post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey test revealed that means for each of the indicators were significantly different across the groups. Overall, the four groups reflected varying degrees of coping, with consistent differences between the groups on all nine scales. However, there appeared to be relative differences within the groups in the frequency with which group members engaged in the different coping strategies. The Disengaged Coping Group showed a preference for avoidance-oriented strategies (i.e., humor and mental disengagement) over more approach-oriented strategies. The Independent Coping Group did not report engaging in venting or social support as much as the other strategies, whereas the Social Support Seeking Group showed a preference for social support seeking strategies. Finally, the Active Coping Group scored high on all of the coping scales with a preference for approach-oriented strategies.

Table 4.

Means and standard deviations (SD) of latent class indicators for the four COPE groups.

| Group | AC | D | ESS | H | ISS | MD | P | RC | VE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Disengaged Copers (n = 153) | 5.79 (1.64) | 5.07 (1.78) | 4.91 (1.15) | 7.25 (3.44) | 5.17 (1.35) | 8.12 (2.83) | 5.56 (1.81) | 6.34 (2.88) | 5.93 (2.32) |

| 2Independent Copers (n = 375) | 8.72 (2.07) | 6.04 (2.18) | 7.67 (1.61) | 8.54 (3.13) | 7.96 (1.60) | 8.94 (2.29) | 8.99 (2.38) | 8.33 (3.60) | 7.28 (2.49) |

| 3Social Support Seekers (n = 300) | 9.93 (1.99) | 6.79 (2.70) | 11.70 (1.66) | 9.26 (3.33) | 11.35 (1.57) | 10.08 (2.34) | 10.13 (2.33) | 9.45 (3.85) | 9.79 (2.75) |

| 4Active Copers (n = 122) | 13.19 (2.09) | 8.80 (3.81) | 14.50 (1.60) | 11.23 (3.64) | 14.42 (1.32) | 11.53 (2.74) | 13.63 (2.06) | 11.33 (4.31) | 12.39 (2.79) |

| F | 331.08** | 51.02** | 1206.33** | 33.81** | 1094.72** | 54.44** | 298.72** | 45.90** | 186.34** |

Note. AC, Active Coping; D, Denial; ESS, Emotional Social Support; H, Humor; ISS, Instrumental Social Support; MD, Mental Disengagement; P, Planning; RC, Religious Coping; VE, Venting Emotions

p < .01

Figure 1.

Profiles of Participants across the Adolescent COPE Scales

Variations in Age, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender across the Four COPE Groups

Chi-square tests examined whether the four COPE groups varied in terms of age, racial/ethnic composition, and gender. There were no group differences in age, Χ2 (6) = 6.07, p = n.s., or race/ethnicity (European American, African American, Latino American, or Asian American), Χ2 (12) = 16.10, p = n.s.. However, there were significant differences in the gender composition across the 4 groups, Χ2 (3) = 89.30, p < .05, with more boys than girls in the Disengaged Coping (66% male) and Independent Coping Groups (60% male) and more girls than boys in the Social Support Seeking (66% female) and Active Coping Groups (75% female). Figure 2 shows the mean scores for the groups across the COPE scales for girls and boys separately.

Figure 2.

Mean scores across the COPE Scales for girls (above) and boys (below)

Differences in Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms among the Four COPE Groups

The four COPE groups were compared on depressive and anxiety symptoms in a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Results showed significant main effects for the depression scale and all of the anxiety scales except social anxiety (see Table 5). All main effects remained significant with gender controlled. Post-hoc paired comparisons among the four COPE Groups revealed that the Independent Coping Group reported significantly less depressive symptoms than all of the other groups. The Disengaged Coping and Independent Coping Groups also reported significantly less separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, and total anxiety than the Social Support Seeking and Active Coping Groups.

Table 5.

Comparison of the four COPE groups on the depressive and anxiety symptom subscales.

| Group | Depressive Symptoms |

Social Anxiety Symptoms |

Separation Anxiety Symptoms |

Generalized Anxiety Symptoms |

Total Anxiety Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Disengaged Copers | 36.98a (12.39) | 3.77a (3.60) | 1.30a (2.11) | 3.88a (4.25) | 12.69a (12.45) |

| 2 Independent Copers | 33.69b (9.76) | 4.10a (3.30) | 1.63a (1.94) | 4.22a (3.66) | 13.29a (9.68) |

| 3 Social Support Seekers | 36.36a (10.90) | 4.64a (3.41) | 2.62b (2.45) | 5.76b (3.99) | 18.72b (12.13) |

| 4 Active Copers | 37.42a (12.64) | 4.63a (3.66) | 3.24b (3.23) | 7.40c (4.92) | 22.44c (15.53) |

| F(3, 785) | 4.47* | 2.64* | 20.749* | 20.82* | 21.92* |

| Adjusted R2 | .013 | .006 | .070 | .070 | .074 |

Note. Standard deviations are in parentheses. Different subscripts indicate significant differences between means at p < .05. Means that share the same subscript are not significantly different.

p < .05

Discussion

Despite the multidimensional nature of adolescent coping (Ohannessian et al., 2010; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007), prior research has focused on risk associated with the use of individual strategies, including approach strategies (e.g., social support; Cicognani, 2011) and avoidant strategies (e.g., behavioral disengagement; Horwitz et al., 2011). Rather than studying a single type of coping, the current study identified patterns of coping across nine different strategies. Latent profile analysis (LPA) addressed the first study question of whether a self-report measure of adolescent coping could differentiate groups of adolescents with a preference for certain strategies. The LPA identified four groups of adolescents who varied in the degree to which they reported engaging in the coping strategies. Coping scale means differed across all of the groups; however, adolescents within each group reported relative preference for certain strategies. The Disengaged Coping Group reported relative preference for avoidance strategies, the Independent Coping Group endorsed relatively less support-seeking, the Support Seeking Group reported relatively more support-seeking, and the Active Coping Group reported using approach strategies relatively more than avoidance strategies.

The second research aim was to examine whether the composition of the different groups varied in terms of demographic characteristics. The groups did not differ in mean age or race/ethnicity. However, there were gender differences in the composition of the groups, with more boys in the Disengaged and Independent Coping Groups and more girls in the Support Seeking and Active Coping Groups. These findings are consistent with prior research indicating that adolescent girls report engaging in coping strategies, particularly approach strategies, more than boys (Griffith et al., 2000). These findings are also consistent with prior studies showing that adolescent girls rely more on social support strategies than boys (Seiffge-Krenke, 2011).

Our final research aim was to examine whether the groups differed in depressive and anxiety symptoms. Adolescents in the Active Coping Group who reported engaging in the different coping strategies the most when faced with stress also reported the most anxiety. Individuals in the Independent Coping Group appeared to be the healthiest in terms of internalizing symptoms, reporting the lowest levels of depression and anxiety. Consistent with prior research on gender differences in internalizing problems, there were more girls than boys in the groups that reported the highest levels of internalizing symptoms (Bekker & van Mens-Verhulst, 2007). In addition, adolescent boys were more likely than girls to fall into the Independent Coping Group that reported the least internalizing symptoms (Kessler et al., 2005; Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994). However, given that group differences in depression and anxiety remained after controlling for gender, gender differences in coping do not appear to account for these findings.

It is somewhat counterintuitive that the Active Coping Group reported the highest amount of anxiety symptoms. However, it is possible that this group reported high levels of coping and high levels of anxiety because they experience more stress than the other groups. Thus, overall level of stress may be a potential third variable accounting for this finding. It is also possible that the Active Coping Group experiences high levels of anxiety because their coping efforts are ineffective due to difficulties with attentional control (Eysenck & Derakshan, 2011). A third explanation is that the Active Coping Group experiences certain types of stressors, such as uncontrollable stressors (e.g., a medical illness), that are not amenable to approach-oriented strategies (Dashora et al., 2011). Research suggests that in certain situations, the use of avoidant strategies might better alleviate anxiety because they enable youth to focus instead on positive events when nothing can be done to change the stressfulness of the situation (Dashora et al., 2011). As such, future research focusing on coping and internalizing symptoms should consider the types of stress in relation to the different coping strategies used.

Importantly, the LPA identified a group of adolescents who reported the fewest depressive and anxiety symptoms. This group was labeled the Independent Coping Group because they were less likely to report using venting and social support seeking strategies. The Independent Coping Group also reported only moderate amounts of coping across the strategies. This finding suggests that the relationship between amount of coping and internalizing problems may be curvilinear – healthy individuals engage in moderate amounts of coping, whereas depressed individuals tend to engage in either high or low amounts of coping. On one hand, the Independent Coping Group may report lower levels of coping than the Social Support Seeking and Active Coping Groups because they do not experience as much stress. On the other hand, their relative use of avoidance-oriented strategies may be more effective in coping with the types of stressors they experience (Griffith et al., 2000). Finally, future research might test whether the groups differentiate depressed adolescents (the disengaged copers) from adolescents with comorbid depression and anxiety (the social support seeking copers and active copers).

In sum, this study employed a sophisticated analytic approach to examine the multidimensional nature of adolescent coping and associated risk for internalizing problems. However, a few caveats should be noted. All of the measures included in the study were self-report. Although self-report measures have been found to yield valid and reliable data (Dekovic et al., 2006; LaForge, Borsari, & Baer, 2005), it would be informative for future investigations to validate these results with other methodology. It also is possible that the findings from this study may not generalize to other populations, such as a clinical sample of youth who meet criteria for a psychiatric disorder, older or younger youth, or adolescents living outside of the Mid-Atlantic United States. In addition, data were collected at a single time point, and, thus, conclusions cannot be drawn regarding causal relationships among variables. Finally, third variables (e.g., type of stress, level of stress) may account for the relationship between coping and symptoms.

Nevertheless, the study’s multidimensional approach facilitates an understanding of the relationship between the use of multiple coping strategies and internalizing symptoms among adolescents. Results from this study demonstrate that adolescents between the ages of 14 and 16 engage in a variety of different coping strategies. Given the multidimensional nature of coping, future research should continue to examine coping profiles, rather than individual strategies, as predictors of symptomatology, while taking into account type and overall level of stress. The findings from this study have important implications for treatments that aim to improve adolescent coping. According to the results, clinicians cannot assume that adolescents high in internalizing symptoms are not engaging in coping, including adaptive types of coping, to manage stress. Rather than focusing intervention efforts on the general development of coping skills, such interventions might better serve adolescents by helping them choose appropriate combinations of strategies in response to specific types of stressors.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Adolescent Adjustment Project for their help with data collection.

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Health (K01-AA015059).

Contributor Information

Joanna Herres, Drexel University.

Christine McCauley Ohannessian, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and University of Connecticut School of Medicine.

References

- Aldridge AA, Roesch SC. Developing coping typologies of minority adolescents: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31(4):499–517. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhan J, Auyeung B. Coping with stress across the lifespan: Absolute vs. relative changes in strategy. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28(4):298–317. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2007.04.002. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JA. Assessing the transitions to middle and high school. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19(1):3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bekker MH, van Mens-Verhulst J. Anxiety disorders: sex differences in prevalence, degree, and background, but gender-neutral treatment. Gender Medicine. 2007;4:S178–S193. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(07)80057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Cully M, Brent DA, McKenzie S. Screen for child anxiety related disorders (SCARED) – parent form and child form (8 years and older) In: VandeCreek L, Jackson TL, editors. Innovations in clinical practice: Focus on children & adolescents. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 2003. pp. 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Connor-Smith J. Personality and coping. Annual review of psychology. 2010;61:679–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicognani E. Coping strategies with minor stressors in adolescence: Relationships with social support, self-efficacy, and psychological well-being. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2011;41(3):559–578. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AT. Coping with interpersonal stress and psychosocial health among children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(1):11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Orosan PG, Grant KE. Adolescent stress and coping: Implications for psychopathology during adolescence. Journal of adolescence. 1993;16(3):331–349. doi: 10.1006/jado.1993.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith J, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(1):87–127. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith JK, Compas BE, Wadsworth ME, Thomsen AH, Saltzman H. Responses to stress in adolescence: measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(6):976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashora P, Erdem G, Slesnick N. Better to bend than to break: coping strategies utilized by substance-abusing homeless youth. Journal of Health Psychology. 2011;16(1):158–168. doi: 10.1177/1359105310378385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekovic M, Ten Have M, Vollebergh W, Pels T, Oosterwegel A, Wissink IB, De Winter A, Verhulst FC, Ormel J. The cross-cultural equivalence of parental rearing measure: EMBU-C. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2006;22:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan DF. Growing up under the gun: Children and adolescents coping with violent neighborhoods. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1996;16:343–356. doi: 10.1007/BF02411740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Conradt J, Sasagawa S, Ollendick TH. Prevention of anxiety symptoms in children: Results from a universal school-based trial. Behavior therapy. 2012;43(2):450–464. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenbeck H, Kohlmann CW, Lohaus A. Gender differences in coping strategies in children and adolescents. Journal of Individual Differences. 2007;28(1):18. [Google Scholar]

- Evans LD, Kouros C, Frankel SA, McCauley E, Diamond GS, Schloredt KA, Garber J. Longitudinal relations between stress and depressive symptoms in youth: Coping as a mediator. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015;43:355–368. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9906-5. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck MW, Derakshan N. New perspectives in attentional control theory. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;50(7):955–960. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble WC. Perceptions of controllability and other stressor event characteristics as determinants of coping among young adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23(1):65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C. Conceptualization and measurement of coping during adolescence: A review of the literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2010;42(2):166–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01327.x. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison CZ, Addy CL, Jackson KL, McKeown RE, Waller JL. The CES-D as a screen for depression and other psychiatric disorders in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:636–641. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199107000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Elder GH, Simons RL. Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:467–483. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez NA, Tein J, Sandier IN, Friedman RJ. On the limits of coping: Interaction between stress and coping for inner-city adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2001;16:372–395. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith MA, Dubow EF, Ippolito MF. Developmental and cross-situational differences in adolescents' coping strategies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29(2):183–204. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1005104632102. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AG, Hill RM, King CA. Specific coping behaviors in relation to adolescent depression and suicidal ideation. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34(5):1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Chassin L. Stress and coping among children of alcoholic parents through the young adult transition. Development and psychopathology. 2004;16(04):985–1006. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE, Luxton DD. Vulnerability-stress models. Development of Psychopathology: A Vulnerability-Stress Perspective. 2005:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd Edition ed. New York: The Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- LaForge RG, Borsari B, Baer JS. The utility of collateral informant assessment in college alcohol research: Results from a longitudinal prevention trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:479–487. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis KM, Byrd DA, Ollendick TH. Anxiety symptoms in African-American and Caucasian youth: Relations to negative life events, social support, and coping. Journal of Anxiety disorders. 2012;26(1):32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litman JA. The COPE inventory: Dimensionality and relationships with approach- and avoidance-motives and positive and negative traits. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;41(2):273–284. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.032. [Google Scholar]

- Litman JA, Lunsford GD. Frequency of use and impact of coping strategies assessed by the COPE inventory and their relationships to post-event health and well-being. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14(7):982–991. doi: 10.1177/1359105309341207. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105309341207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TR, Robins CJ, Morse JQ, MorKrause ED. A mediational model relating affect intensity, emotion inhibition, and psychological distress. Behavior Therapy. 2001;32:519–536. [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Ollendick T, King N, Bogie N. Three traditional and three new childhood anxiety questionnaires: Their reliability and validity in a normal adolescent sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40(7):753–772. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. 1998–2010 Mplus user‘s guide. Muthén and Muthén. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological bulletin. 1994;115(3):424. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM. Media use and adolescent psychological adjustment: An examination of gender differences. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2009;18(5):582–593. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9261-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Bradley J, Waninger K, Ruddy K, Hepp BW, Hesselbrock V. An examination of adolescent coping typologies and young adult alcohol use in a high-risk sample. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2010;5(1):52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Lerner RM, Lerner JV, von Eye A. Perceived parental acceptance and early adolescent self-competence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(4):621. doi: 10.1037/h0080370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang J, Strodl E, Oei TS. The factor structure of the COPE questionnaire in a sample of clinically depressed and anxious adults. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2013;35(2):264–272. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10862-012-9328-z. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps SB, Jarvis PA. Coping in adolescence: Empirical evidence for a theoretically based approach to assessing coping. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23(3):359–371. [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Cohen LJ. Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist. 1986;41:813–819. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.41.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD. Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer MG, Pfeiffer S, Spence SH. Life events, coping and depressive symptoms among young adolescents: A one-year prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;117(1):48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. The development of coping. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:119–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. Causal links between stressful events, coping style, and adolescent symptomatology. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23(6):675–691. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I, Klessinger N. Long-term effects of avoidant coping on adolescents' depressive symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29(6):617–630. [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. Coping with relationship stressors: A decade review. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(1):196–210. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(2):216–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Campione-Barr N, Metzger A. Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:255–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark L, Spirito A, Williams D, Guevremont D. Common problems and coping strategies I: Findings with normal adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1989;17:205–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00913794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum LS, Varjas K, Meyers J, Parris L. Coping strategies and perceived effectiveness in fourth through eighth grade victims of bullying. School Psychology International. 2011;32(3):263–287. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0143034311402309. [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Stahl MA, Stemmler M, Petersen AC. Approach and avoidant coping: Implications for adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24:649–665. [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. Causal links between stressful events, coping style, and adolescent symptomatology. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23:675–691. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I, Klessinger N. Long-term effects of avoidant coping on adolescents' depressive symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:617–630. [Google Scholar]

- Valentiner DP, Holahan CJ, Moos RH. Social support, appraisals of event controllability, and coping: An integrative model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66(6):1094. [Google Scholar]

- Waters SK, Lester L, Cross D. Transition to secondary school: Expectation versus experience. Australian Journal of Education. 2014 0004944114523371. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Orvaschell H, Padian N. Children’s symptom and social functioning self-report scales: comparison of mothers’ and children’s reports. Journal of Nervous Mental disorders. 1980;168:736–740. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills, Sandy JM, Yaeger AM, Cleary SD, Shinar O. Coping dimensions, life stress, and adolescent substance use: A latent growth analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:309–323. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan KH, Bentler PM. Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data. Sociological methodology. 2000;30(1):165–200. [Google Scholar]