Abstract

The effectiveness of community health workers (CHWs) as health educators and health promoters among Latino populations is widely recognized. The Affordable Care Act created important opportunities to increase the role of CHWs in preventive health. This article describes the implementation of CHW-led, culturally specific, faith-based program to increase physical activity among churchgoing Latinas. This study augments previous research by describing the recruitment, selection, training, and evaluation of CHWs for a physical activity intervention targeting multiple levels of the Social Ecological Model.

Keywords: built environment, churches, community health workers, health promotion, Hispanic Americans, intervention studies, physical activity

THE COMMUNITY HEALTH WORKER (CHW) model has been established as an effective model for health promotion worldwide (Naimoli et al., 2014). Although titles vary—CHWs, promotoras, lay health advisers—CHWs typically are individuals without formal education who are trained to promote health and advocate for change in their communities (Carrasquillo et al., 2014). Increasingly, there is widespread involvement of CHWs in interventions, particularly in diabetes control (Carrasquillo et al., 2014; Castillo at el., 2015; Little et al., 2014; Rothschild et al., 2013), cardiovascular disease prevention (Balcazar et al., 2014; Spinner & Alvarado, 2012), and reproductive health (Lechuga et al., 2015). Several studies have used the CHW model to promote physical activity (PA) (Ayala, 2011; Koniak-Griffin et al., 2015; Staten et al., 2011).

The effectiveness of CHWs as health educators and health promoters among Latino populations is widely recognized (Medina et al., 2007; Messias et al., 2013; Saad-Harfouche et al., 2011; Waitzkin et al., 2011). Farrell et al. (2009) identified the following theoretical constructs as likely to explain their effectiveness: cultural competence, existence of informal networks, social support, and a positive source of social influence. CHWs are particularly effective because of the cultural and linguistic connections they have with the communities they serve.

CHWs as part of health care teams have gained the attention of the US government, particularly given their ability to reach underserved populations. In May 2011, the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health created the CHW initiative, which is guided by a committee of 15 CHWs from across the country and provides information on ways to improve community-based health outreach to Latino populations (WestRasmus et al., 2012). More importantly, the Affordable Care Act has increased funding opportunities for CHW programs, recognizing the need for community-based health programs that help racial/ethnic minority populations overcome cultural and linguistic barriers to health care (Shah et al., 2014).

Although the importance of CHWs in health promotion has been established, CHW selection, training, and evaluation are less understood. O'Brien et al. (2009) noted the need for better descriptions of the recruitment and selection process. Ayala (2011) identified the lack of CHW trainings for PA interventions, whereas Messias et al. (2013) noted the lack of evaluation of CHW roles. The present study adds to this body of research by describing the recruitment, selection, training, and evaluation of CHWs as part of a CHW-led multilevel intervention promoting PA.

METHODS

Study design

Fe en Acción (Faith in Action) is a community-based, group-randomized trial that aims to increase moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) among churchgoing Latinas in San Diego, California. Sixteen Catholic churches were randomly assigned to either the PA intervention or the cancer screening intervention, both CHW-led. Adult female members of participating churches were invited to enroll and were followed from baseline to 12 months and 24 months postbaseline. On average, 27 women were enrolled in each of the 16 churches (n = 436). At each church, 2 to 3 women were recruited, hired, and trained by research staff as CHWs to lead either the PA intervention or the cancer screening intervention. Study activities began in 2010 and while CHW recruitment, selection, and training are completed, intervention activities are scheduled to conclude in September 2015.

Setting and population

Approximately half of all US Latinos live in California and Texas (Ennis et al., 2011). San Diego has a diverse population of approximately 3.1 million where 32% report Hispanic/Latino heritage (US Census Bureau, 2010). A majority of Latinos (68%) identify as Roman Catholic and their representation within the US Catholic Church is expected to grow (Pew Research Center, 2007). The Roman Catholic Diocese of San Diego (2010) encompasses a large and geographically diverse area, comprising 97 parishes and 14 missions with 982 183 parishioners, approximately 30% of the county's entire population (US Census Bureau, 2010).

Intervention description

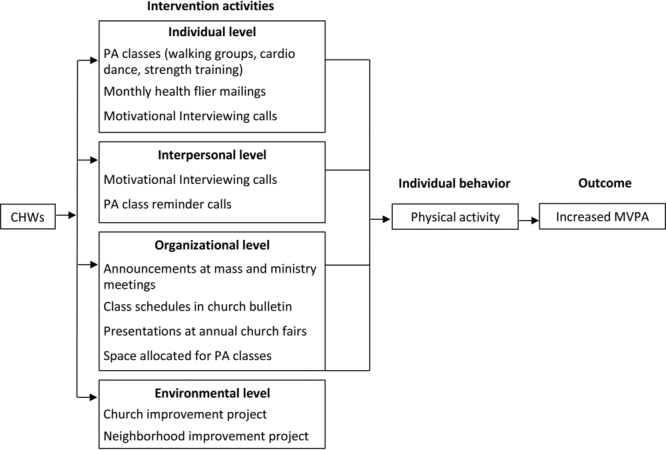

The PA intervention addresses multiple levels of the Social Ecological Model (SEM) (Sallis et al., 2002). The SEM was chosen because a person's behavior is influenced by social, cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Interventions informed by SEM target multiple levels and are expected to be more effective than those intervening at only one level (McLeroy et al., 1988; Sallis et al., 2002; Stokols, 1996).

This study is intervening at 4 levels of the SEM (see the Figure). At the individual level, 3 types of free exercise classes are offered at or near the church site: walking groups, cardio dance, and strength training. The variety of classes offered targets women with varying fitness levels and activity preferences. Physical activity classes are open to all church members. Study participants receive monthly culturally tailored educational handouts addressing 14 topics including proper hydration, healthy eating, injury prevention, and myths about PA. Included in these mailings is a current schedule of PA classes. At the interpersonal level, CHWs implement Motivational Interviewing (MI) phone calls to address barriers to PA, reinforce PA efforts, and provide appraisal and emotional support. Motivational Interviewing is a counseling approach that allows individuals to develop their own arguments for change, not prematurely pushing an individual to change and encouraging individuals to find meaning in their decisions (Resnicow et al., 2002). The MI component was pilot-tested and modeled after the Resnicow et al. MI guide. CHWs ask study participants about their PA frequency, duration, barriers to increasing activity or intensity, benefits of increasing PA, solutions to these barriers, and to articulate the link between their values and benefits of engaging in PA. Each call lasts approximately 30 minutes, and study participants receive MI calls every 3 to 4 months during the 2-year intervention, for a total of 5 calls. At the organizational level, churches provide indoor and outdoor spaces for PA classes, as specified in written agreements with church leaders. In addition, church leaders and CHWs make announcements about the PA classes at mass and ministry meetings and class schedules are published in church bulletins. At the environmental level, CHWs engage study participants in neighborhood walk audits and identify areas for improvement in and around the church parcel. The study participants work with the CHWs to improve the built environment in their communities to promote PA.

Figure.

Multilevel intervention model. CHW, community health worker; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA, physical activity.

CHW recruitment and selection

The process for recruiting CHWs occurred simultaneously with participant recruitment. In each church, bilingual/bicultural research assistants solicited candidates via announcements at Spanish language masses, meetings, and printed in church bulletins. Because the study design required research assistants and study participants to be blinded to condition at baseline, recruitment of CHWs included few details about the job description until the very last stages of the process. Interested individuals were asked to submit a 1-page application to the research staff or church office.

Eligibility requirements for CHWs included those between 18 and 65 years of age, self-identify as Latina, Spanish language fluency, ability to legally work in the United States, and self-reported PA behaviors. Qualified individuals were screened by phone to assess their ability to commit to the 2-year intervention and availability for training. The top candidates at each church were then scheduled for an interview with the intervention coordinator (IC). Interviews were conducted in Spanish or English, depending on applicant preference. If the interview was conducted primarily in English, 2 or 3 questions were asked in Spanish to assess the applicant's level of fluency. Applicants were asked about their experience teaching in community settings, including teaching catechism, leading a ministry, or other leadership roles. Applicants were asked to describe how often they engaged in PA and whether or not they had a medical condition preventing them from safely engaging in MVPA. The IC sought candidates who practiced regular PA and were familiar with group exercise classes. Because of the faith-based setting and orientation of the intervention, applicants' involvement in the church and duration of membership were additional areas of inquiry. Following the interviews, references for each applicant were contacted and asked about the candidate's leadership skills, strengths, and weaknesses and involvement in the local community.

In each church, the top 2 to 3 candidates were offered paid CHW positions ($10 per hour). CHWs worked 10 hours per week and were paid twice a month through San Diego State University. As part-time employees, they did not receive benefits. In some cases, CHWs were unable to fulfill the 2-year commitment and new CHWs were recruited and hired in a similar fashion.

CHW training

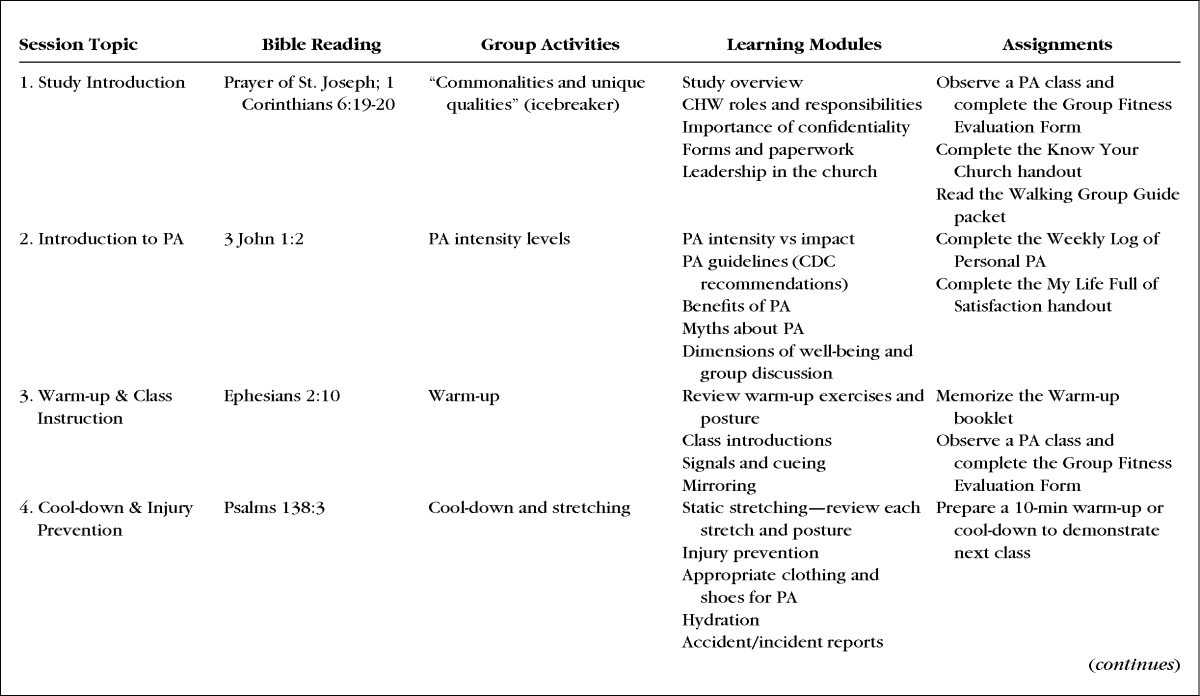

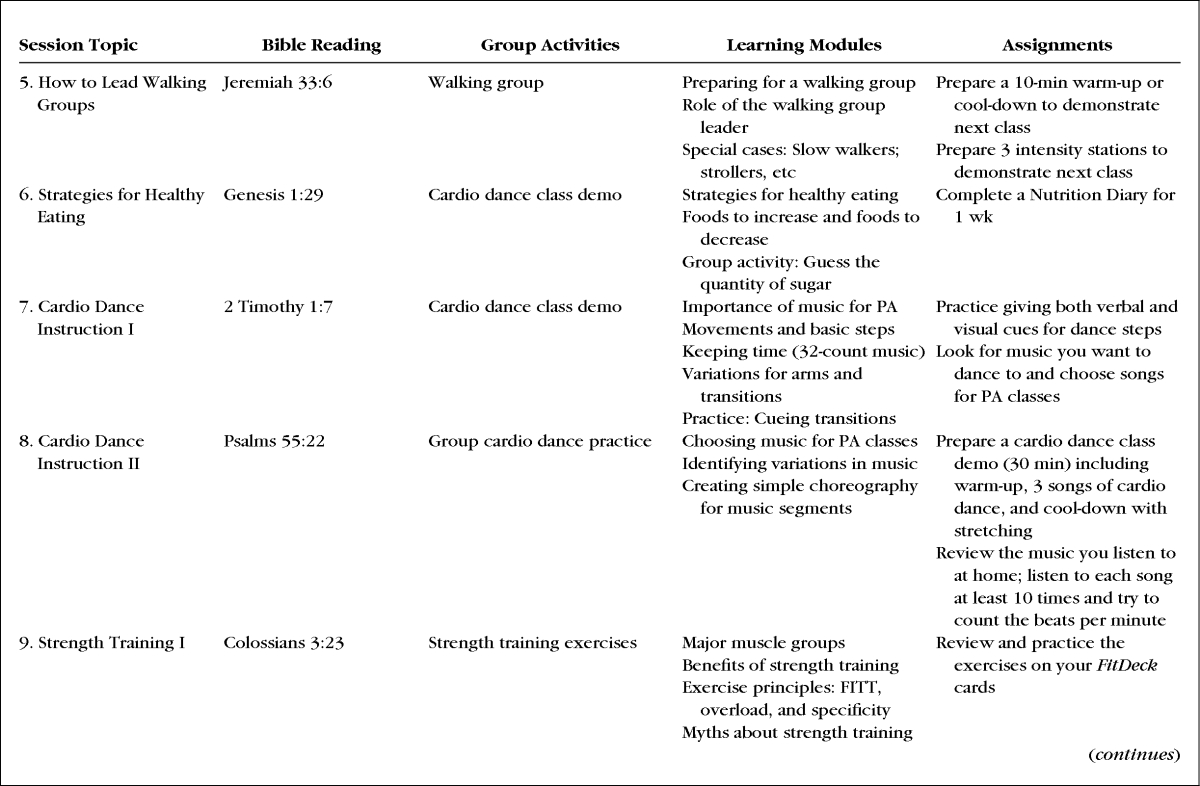

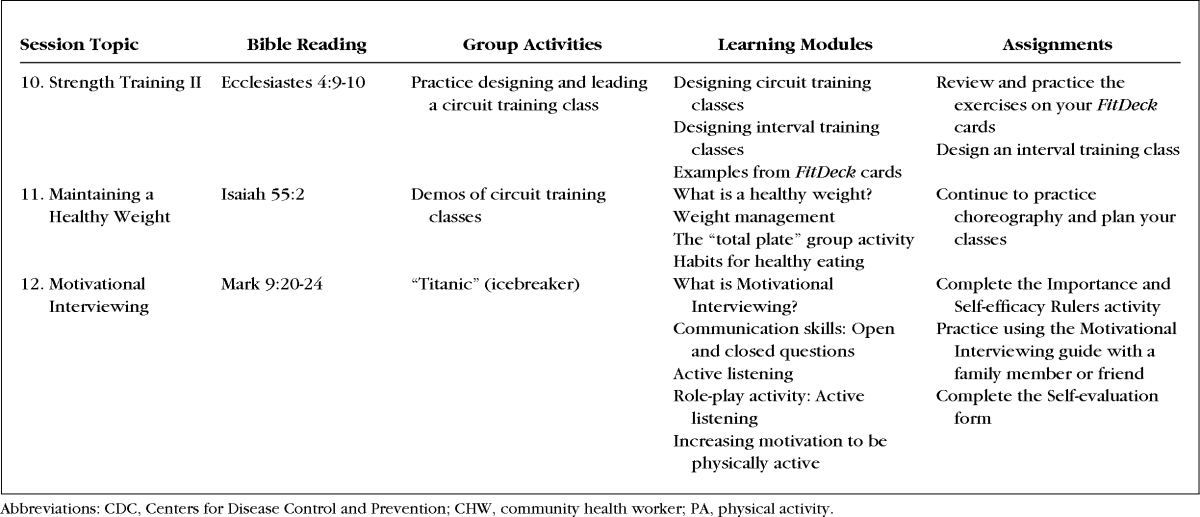

The IC and the PA specialist met with the CHWs twice a week for 2 hours each session, totaling 12 sessions and 24 hours of training during 6 weeks. CHWs received a Spanish language training manual containing didactic and interactive contents for all 12 sessions (see the Table). The curriculum was developed by a team consisting of behavioral scientists, an exercise physiologist, specialists in exercise, PA, and kinesiology, and public health graduate students. Using recommendations from the Aerobics and Fitness Association of America and the American Council on Exercise, both national fitness instructor training programs, the curriculum focused on safe exercises for largely inactive individuals. Attention was placed on appropriate warm-up, gradual increase to vigorous PA, and cool-down. Training sessions began with prayer and Bible verses focusing on physical health, serving others, and leadership. During training, CHWs were assigned homework, including designing strength training classes, developing cardio dance choreography, practicing stretching exercises, and other activities to enhance their learning. All CHWs were certified in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and First Aid. Following completion of training, CHWs demonstrated a 30-minute class to the IC and the PA specialist, with the following compulsory elements: 10-minute warm-up, 10 minutes of cardio dance or strength training exercises, and a 10-minute cool-down. The IC and the PA specialist completed written evaluations and provided verbal feedback. Those who reached a level of competence adequate to begin teaching classes received a certificate of completion, a project pin, 2 project exercise shirts to wear while teaching, an exercise mat, towel, water bottle, backpack, sun visor, and class instructional materials. The CHWs' final training session focused on MI, giving them the tools to use a modified version of a script developed by Resnicow et al. (2002). The IC trained the CHWs in MI and included strategies to support PA such as time management, setting realistic PA goals, and eliciting support from family and friends to engage in PA.

Table. Faith in Action Physical Activity CHW Training Curriculum.

Six months after the start of intervention activities, Circulate San Diego (www.circulatesd.org) conducted an 8-hour training session with CHWs on the impact of the built environment on PA, advocacy, and community organizing. Circulate San Diego is a nonprofit organization connecting neighborhoods and people with various forms of transportation. CHWs used walk audits developed by Circulate San Diego both to identify built environment targets of change and to develop solutions improving the church and surrounding neighborhood for walking and other forms of PA. These targets included the removal of pedestrian barriers, improvements to community safety, aesthetic improvements, and increased lighting. CHWs were encouraged to attend and participate in community, legislative, and parish council meetings to learn about community resources, leverage support, and facilitate built environmental changes.

Study documents collected by CHWs

To track program participation, CHWs collect PA class attendance sheets and submit them to the PA specialist. Participants not enrolled in the study are counted but not tracked individually. A record of all PA classes is gathered using the attendance sheets and verified with CHWs' weekly reports. In both forms, CHWs are asked to report the date, time, location, and type of class offered.

For all MI calls, CHWs are required to use a standard guide (Resnicow et al., 2002). Eight attempts to contact are made. For completed calls, the CHW submits the MI guides including the participant's responses and any notes the CHW took during the call. The guide provides a script for the CHW to help the participant set PA goals and space for the CHW to take notes for follow-up purposes. During the following MI call, the CHW uses notes from the previous call to help the CHW follow-up on the participant's goals.

CHW booster trainings and meetings

To maximize intervention fidelity, CHWs meet regularly with the IC or PA specialist throughout the 2-year intervention. During the first 2 months of the intervention, CHW meetings were weekly; in months 4 to 12, meetings occurred biweekly. In the second year of intervention, CHW meetings are monthly, the exception being a few cases in which a CHW left the study and the new CHW required greater support. During these meetings, CHWs report upon the progress of the PA classes and completion of MI calls, discuss any challenges they face, and receive feedback. In addition, CHWs submit class attendance sheets, weekly reports, call logs, and completed MI guides.

The IC and the PA specialist plan booster trainings with CHWs. Training topics include correct posture for strength training, MI techniques, accurate completion of paperwork, and safety precautions. Booster trainings are conducted at participating churches or in CHWs' homes, depending on space available. Not only do booster trainings provide an opportunity to cross-train all CHWs in the same topics but they also give the CHWs a venue to meet and network with their peers, creating community among them.

Evaluation of CHWs' performance

In addition to the feedback provided during CHWs meetings, 2 methods are used to evaluate the work of CHWs. First, the PA specialist attends and observes PA classes taught by CHWs and completes a form assessing fidelity. CHWs adhere to a strict set of guidelines including a standard introduction and prayer, providing appropriate exercise options, and leading a discussion at the end of class on a health topic related to PA. Following the observation, the PA specialist meets one on one with the CHW to provide feedback on observed strengths and suggestions for areas needing improvement.

The second CHW evaluation method uses the System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time for Group Exercise Classes (SOFIT-X) instrument to assess the quality of PA classes. SOFIT-X is an objective measure of the type, intensity, and quality of PA classes (Duesterhaus, 2011). Trained assessors evaluate PA classes using this observational tool that audibly prompts the recording of observations on class participants' posture, intensity, and class context. In addition, the Instructor Behavior Checklist assesses the quality of instruction. CHWs are given feedback from the PA specialist following the SOFIT-X assessments.

Finally, questions about CHW performance are included in the process evaluation surveys administered to study participants at 12 and 24 months. Participants are asked to rate the difficulty of classes, the number of contacts they have had with the CHWs at their church, and the quality of the MI calls they receive and to provide any suggestions for the project. These data are still being collected, as the study has not yet completed intervention at all sites.

RESULTS

CHW characteristics

Demographics were collected at baseline from the 25 CHWs enrolled in the PA condition. The average age was 36.8 (SD = 10.8) years, 91% had at least a high school education, 27% reported less than $2000 per month in household income, 87% were born outside of the United States, and their average number of years in the United States was 18.7 (SD = 11.9). Only 2 had prior experience as CHWs, and just 1 had experience leading group exercise classes. All 25 had various experience with PA including walking, running, attending dance classes, going to the gym, cycling, aerobics, and boot camp classes. Those with experience in group exercise classes faced fewer challenges in completing the PA training than those who reported only walking for exercise. Fourteen reported involvement in church activities including serving as a lector, leading children's ministry, serving as Eucharistic ministers, participating in Bible studies, and volunteering with outreach ministries.

CHW retention rate

Of the 25 CHWs hired and trained for the PA condition, 15 (65%) completed the entire 2-year study and the final 2 are set to complete the final wave of intervention in September 2015 (for a final retention rate of 17/25 or 68%). Of the 8 who did not complete the program, 2 found other employment offering more hours, 2 moved out of the area, 1 left because of a high-risk pregnancy, and 3 were terminated for poor performance (eg, arriving late to classes, not completing required MI calls).

Environmental projects

Study participants, CHWs, and project staff identify and plan environmental improvement projects. CHWs are asked to complete action plans identifying their roles and milestones toward project completion. Upon completion of the project, CHWs submit final written reports including all meeting notes, rosters, and action plans used in project planning and a summary including pictures documenting changes. Of the 6 churches that have completed the intervention phase, 5 completed church projects including building gardens, painting parking lots, and improving aesthetics on church grounds and all 6 completed neighborhood projects including park cleanups, trail restoration, and sidewalk improvements. The final 2 churches plan to complete both church and neighborhood projects over the next 6 months.

PA specialist evaluations

During the course of the intervention, the PA specialist conducted 160 observations of 20 CHWs leading PA classes. Although all components averaged “good” or “excellent,” the 2 areas needing the most improvements were warm-up and cool-down and the area with the greatest variability across CHWs was strength training.

SOFIT-X evaluations

A total of 28 SOFIT-X assessments were completed on 28 CHW-led classes. On average, participants engaged in MVPA 65% of class time, which was the level of activity expected. The quality of all class instruction was high, with a mean score on the Instructor Behavior Checklist of 19.4 (SD = 2.3) of 23.

CONCLUSIONS

The resources, training, and time needed to prepare CHWs for roles targeting multiple levels of the SEM are often overlooked. This study contributes to literature detailing recruitment and training processes needed for successful CHW-led PA promotion projects (Elder et al., 2011). In addition, emerging research is showing the influential role of CHWs in advocating for environmental changes (Arredondo et al., 2013).

Although it is feasible to train CHWs to lead multilevel interventions, the resources required are significant. In this study, the involvement of the PA specialist and the IC was integral to CHWs' success. Regular meetings, booster trainings, class observations, and support were necessary. Rigorous PA training including correcting posture, developing choreography to music, and designing PA classes was integral to intervention implementation. While the intensity and quality of PA classes were high, effective PA instructors often lacked in other areas, such as data collection, timely reporting of hours, and personal time management. Some CHWs struggled to complete paperwork and required individual training and frequent reminders to submit paperwork. For many, this was their first formal job, requiring time from the IC and the PA specialist to develop skills in time management and organization.

While the CHWs succeeded in leading MVPA classes, some components including MI calls proved more challenging. Additional booster trainings on MI provided CHWs the opportunity to role-play and hone their skills, thus improving their confidence. In some churches, CHWs faced organizational barriers in reserving rooms and garnering support from church leadership, despite the church's agreement to participate in the study. In these cases, the IC met with church leadership to help resolve conflicts and secure space for intervention activities. At the environmental level, most CHWs completed both projects; however, many struggled with the process and required additional support from the PA specialist. Finally, CHWs were required to collect process data, which in another study might be tasked to research staff. A challenge in conducting this multilevel intervention was finding CHWs who could not only lead high-quality MVPA classes but also conduct MI calls, collect process data, and advocate for environmental changes. At times, it was difficult to identify CHW candidates with all the skills needed to accomplish the various components of the intervention, requiring more support and training from the IC and the PA specialist. A potential solution would be to identify CHWs to work separately on different levels of the intervention, not requiring that each CHW possess all the skills needed across all levels.

Particularly among CHWs who completed the 2-year project, many reported improved self-image, a sense of empowerment, and increased PA. CHWs used their experiences on the project to apply to other CHW positions and leadership positions within their churches. They reported a good experience overall and particularly liked the booster trainings, which functioned as a support group where they found trust and friendship with colleagues. The CHWs gained valuable skills including time management, goal setting, and leadership, preparing them for future roles. Most CHWs have continued teaching PA classes in their churches and local communities, despite no longer being paid by the project. Some receive donations from participants and others volunteer their time. One of the benefits of locating the intervention in churches was the opportunity to sustain the project through the existing church community. The churches recognize the CHWs as leaders in the church and continue to allocate space for PA classes.

As CHWs are increasingly included in health care teams, research studies, and health promotion projects, the processes of recruitment, selection, training, and evaluation must be clarified. Beyond the initial training, resources are needed to provide support and feedback to CHWs in the field. This time investment benefits both the CHWs and the organizations. CHWs can take the training and experience from previous projects through their careers, opening up opportunities for future employment. As a workforce of CHWs is created, research projects and health care organizations benefit from having a pool of well-trained CHWs from which to recruit.

Footnotes

This project is funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA138894). The authors acknowledge the many contributions of their Faith in Action Community Health Workers, participating churches, research assistants, and student interns.

No conflicts of interest reported by authors.

REFERENCES

- Arredondo E., Mueller K., Mejia E., Rovira-Oswalder T., Richardson D., Hoos T. (2013). Advocating for environmental changes to increase access to parks: Engaging promotoras and youth leaders. Health Promotion Practice, 14(5), 759–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala G. X. (2011). Effects of a promotor-based intervention to promote physical activity: Familias sanas y activas. American Journal of Public Health, 101(12), 2261–2268. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar H. G., Wise S., Redelfs A., Rosenthal E. L., de Heer H. D., Burgos X., Duarte-Gardea M. (2014). Perceptions of community health workers (CHWs/PS) in the U.S.-Mexico Border HEART CVD study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11, 1873–1884. 10.3390/ijerph110201873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquillo O., Patberg E., Alonzo Y., Li H., Kenya S. (2014). Rationale and design of the Miami Healthy Heart Initiative: A randomized controlled study of a community health worker intervention among Latino patients with poorly controlled diabetes. International Journal of General Medicine, 7, 115–125. 10.2147/IJGM.S56250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo A., Giachello A., Bates R., Concha J., Ramirez V., Sanchez C., Arrom J. (2015). Community-based diabetes education for Latinos: The diabetes empowerment education program. The Diabetes Educator, 36(4), 586–594. 10.1177/0145721710371524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duesterhaus M. P. (2011). A system for observing fitness instruction time in group-exercise classes (SOFIT-X). Unpublished master's thesis, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Elder J. P., McKenzie T. L., Arredondo E. M., Crespo N. C., Ayala G. X. (2011). Effects of a multi-pronged intervention on children's activity levels at recess: The Aventuras para Niños study. Advances in Nutrition, 2(2), 171S–176S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis S. R., Rios-Vargas M., Albert N. G. (2011). The Hispanic population: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs. United States Census Bureau; Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M. A., Hayashi T., Loo R. K., Rocha D. A., Sanders C., Hernandez M., Will J. C. (2009). Clinic-based nutrition and lifestyle counseling for Hispanic women delivered by community health workers: Design of the California WISEWOMAN study. Journal of Women's Health, 18(5), 733–739. 10.1089/jwh.2008.0871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniak-Griffin D., Brecht M. L., Takayanagi S., Villegas J., Melendrez M., Balcázar H. (2015). A community health worker-led lifestyle behavior intervention for Latina (Hispanic) women: Feasibility and outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52, 75–87. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechuga J., Garcia D., Owczarzak J., Barker M., Benson M. (2015). Latino community health workers and the promotion of sexual and reproductive health. Health Promotion Practice. 10.1177/1524839915570632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little T. V., Wang M. L., Castro E. M., Jiménez J., Rosal M. C. (2014). Community health worker interventions for Latinos with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Current Diabetes Reports, 14, 1–16. 10.1007/s11892-014-0558-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy K. R., Bibeau D., Steckler A., Glanz K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina A., Balcázar H., Luna Hollen M., Nkhoma E., Soto Mas F. (2007). Promotores de Salud: Educating Hispanic communities on heart-healthy living. American Journal of Health Education, 38(4), 194–202. 10.1080/19325037.2007.10598970 [Google Scholar]

- Messias D. K., Parra-Medina D., Sharpe P. A., Treviño L., Koskan A. M., Morales-Campos D. (2013). Promotora de Salud: Roles, responsibilities, and contributions in a multisite community-based randomized controlled trial. Hispanic Health Care International, 11(2), 62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimoli J. F., Frymus D. E., Wuliji T., Franco L. M., Newsome M. H. (2014). A community health worker “logic model”: Towards a theory of enhanced performance in low- and middle-income countries. Human Resources for Health, 12, 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien M. J., Squires A. P., Bixby R. A., Larson S. C. (2009). Role development of community health workers. An examination of selection and training processes in the intervention literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(6), S262–S269. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2007). Changing faiths: Latinos and the transformation of American religion. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2007/04/25/changing-faiths-latinos-and-the-transformation-of-american-religion

- Resnicow K., Jackson A., Braithwaite R., Dilorio C., Blisset D., Rahotep S., Periasamy S. (2002). Healthy Body/Healthy Spirit: A church-based nutrition and physical activity intervention. Health Education Research, 17(5), 562–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman Catholic Diocese of San Diego. (2010). About the Diocese of San Diego. San Diego, CA: Author; Retrieved from http://www.diocese-sdiego.org/aboutcdsd.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild S. K., Martin M. A., Swider S. M., Tumialán Lynas C. M., Janssen I., Avery E. F., Powell L. H. (2013). Mexican American trial of community health workers: A randomized controlled trial of a community health worker intervention for Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Public Health, 104(8), 1–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad-Harfouche F. G., Jandorf L., Gage E., Thélémaque L. D., Colón J., Castillo A. G., Erwin D. O. (2011). Esperanza y Vida: Training lay health advisors and cancer survivors to promote breast and cervical cancer screening in Latinas. Journal of Community Health, 36(2), 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis J. F., Owen N., Fisher E. B. (2002). Ecological models of health behavior. In Glanz K., Rimer B. K., Lewis F. M. (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 465–486). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Shah M. K., Heisler M., Davis M. M. (2014). Community health workers and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: An opportunity for a research, advocacy, and policy agenda. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 25(1), 17–24. 10.1353/hpu.2014.0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinner J. R., Alvarado M. (2012). Salud Para Su Carozón—A Latino promotora-led cardiovascular health education program. Family & Community Health, 35(2), 111–119. 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3182465058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staten L., Cutshaw C., Davidson C., Reinschmidt K., Stewart R., Roe D. (2011). Effectiveness of the Pasos Adelante Chronic Disease Prevention and Control Program in a US-Mexico border community, 2005-2008. Preventing Chronic Disease, 9(2), 1–9. 10.5888/pcd9.100301 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. (1996). Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion, 10(4), 282–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. (2010). San Diego County QuickFacts from the U.S. Census Bureau [Data file]. Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/06073.html

- Waitzkin H., Getrich C., Heying S., Rodriguez L., Parmar A., Willging C., Santos R. (2011). Promotoras as mental health practitioners in primary care: A multi-method study of an intervention to address contextual sources of depression. Journal of Community Health, 36(2), 316–331. 10.1007/s10900-010-9313-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WestRasmus E. K., Pineda-Reyes F., Tamez M., Westfall J. M. (2012). Promotores de salud and community health workers: An annotated bibliography. Family & Community Health, 35(2), 172–182. 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31824991d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]