Abstract

Problematic alcohol use and risk for dependence peak during late adolescence, particularly among first-year college students. Although students matriculating into college with depressive symptoms experience elevated risk for alcohol problems, few studies have examined the intervening mechanisms of risk. In this study, we examined depressed mood at college entry on prospective alcohol expectancies, drinking motives, and alcohol outcomes during the first year of college, adjusting for pre-college factors. Participants (N = 614; 59 % female, 33 % non-White) were incoming college students from three universities who completed online self-report surveys prior to matriculating into college and at the end of their first year in college. We utilized path analysis to test our hypotheses. In women, the path that linked depressive symptoms to consequences was primarily attributable to the effect of pre-college drinking to cope on drinking to cope in college, which in turn was associated with alcohol consequences. In men, the effect of depressive symptoms on alcohol consequences in college was independent of pre-college and college factors, thus indicating the need for research that identifies mechanisms of risk in males. Interventions that address coping deficits and motivations for drinking may be particularly beneficial for depressed adolescent females during this high-risk developmental period.

Keywords: Depression, Depressive symptoms, Alcohol, Coping motives, Alcohol expectancies, Adolescents, College students

Introduction

The college years (18–22 years of age) are associated with sharp increases in heavy drinking and the highest prevalence rates of alcohol problems and dependence (Patrick and Schulenberg 2011), with lifetime rates of alcohol dependence peaking between 18 and 20 years (Grant et al. 2004). Relative to older college peers, first-year college students are more likely to drink excessively and experience alcohol-related consequences (e.g., aggressive or disruptive behavior; Bergen-Cico 2000; Harford et al. 2003). As such, the transition to college is identified as a critical period for preventing the development of persistent high-risk drinking patterns (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 2002). College students with depressive symptoms face elevated risk for problematic alcohol use during college (Kenney et al. 2013; Martens et al. 2008a) and are at risk for developing persistent alcohol dependence into adulthood (Meier et al. 2013). Therefore, examining the processes through which depressive symptoms influence subsequent alcohol risk during the first year of college is particularly important to informing early alcohol harm reduction interventions.

College Transitions and Co-occurring Depressed Mood and Alcohol Problems

Late adolescents transitioning into college experience decreased adult supervision and increased independence in decision-making amid new social and academic environments (Kypri et al. 2004). Although this developmental period presents opportunities to explore identities and develop life skills, it is also a time of instability in which students report heightened distress (Arnett 2005; Brown et al. 2008). An estimated 31 % (Ibrahim et al. 2013) to 34 % (Gress-Smith et al. 2015) of college students report at least mild current depressive symptoms, and 11 % meet the criteria for a mood disorder (DSM-IV; Blanco et al. 2008). Moreover, rates of depression appear to be increasing in US college student populations (Reetz et al. 2013; Gallagher 2012); for example, a large-scale nationally representative survey showed significant increases in distress among incoming college students from 2009 to 2014, including frequently feeling “overwhelmed by all they had to do” (27–35 %) in the prior year (Eagan et al. 2014).

Depressed students are at heightened risk for college withdrawal (Hysenbegasi et al. 2005; King et al. 2006) and a range of serious interpersonal and behavioral problems, including alcohol problems (Martens et al. 2008a, b). Relative to non-depressed peers, college students with depressive symptoms are substantially more likely to experience alcohol-related negative consequences (Kenney et al. 2013; Martens et al. 2008a) and symptoms of alcohol dependence (Martens et al. 2008a). Elucidating the pathways linking depressed mood with alcohol problems in college students will provide important insight into this growing public health issue.

Depressive Symptoms Predict Alcohol Problems

The vast majority of empirical research examining the link between negative affect and problematic alcohol use demonstrates that mental health disorders typically start at an earlier age than alcohol use disorders (AUDs) (Kuo et al. 2006; Swendsen et al. 2010). Further, there is evidence that depression predicts increased alcohol consumption over time (Conner et al. 2009). Examining how depressive symptoms predict alcohol problems during late adolescence is critical because the highest prevalence rates of depressive and AUDs occur between late adolescence to early adulthood (Hasin et al. 2007). Therefore, extrapolating the pathways through which depressive status among incoming college students predicts problematic alcohol use during the first year of college is temporally substantiated and may be particularly informative for preventive interventions.

Depressive Symptoms and Potential Mechanisms of Alcohol Risk

Drinking to Cope

Social cognitive theories propose specific mechanisms linking depressive symptoms with problematic alcohol use. Framed in social learning theory, the stressor vulnerability model posits that individuals are inherently motivated to reduce feelings of distress or negative affect, and as a result may depend on drinking to alleviate distress when they lack alternative means of coping (Cooper et al. 1995). However, drinking to cope fails to effectively resolve problems and may lead to problematic alcohol use and alcohol dependence (e.g., Ham et al. 2009). Research on the stressor vulnerability and motivational models of alcohol use indicates that (a) motives are the most proximal antecedent to consumption (Cooper et al. 1995; Hasking et al. 2011); (b) depressive symptoms are related to greater endorsement of motivations for drinking (i.e., social, enhancement, conformity, coping; Thornton et al. 2012); and (c) of all motives, drinking to cope is most strongly tied to depressive affect (O'Hare and Shen 2012) and alcohol-related consequences (Cooper et al. 1995; Kuntsche et al. 2007).

Relative to non-depressed peers, depressed adolescents are more likely to drink to cope with negative affect (e.g., drinking to forget about problems or to cheer you up when you are in a bad mood) (Martens et al. 2008a, b; Rice and Van Arsdale 2010), and drinking to cope predicts increased drinking and problems in general populations of adolescents (Kuntsche et al. 2006) and college students (Evans and Dunn 1995). Further, college students who rely on coping motivated drinking are less likely to transition out of excessive drinking patterns after college than students who do not drink to cope (Littlefield et al. 2010; Merrill and Read 2010). Although several studies demonstrate that drinking to cope mediates the relationship between mental distress and negative alcohol outcomes, these studies have primarily examined the relationship between social anxiety on both alcohol consequences (Lewis et al. 2008; Stewart et al. 2006) and dependence (Ham et al. 2009). Nonetheless, there is compelling evidence that drinking to cope with negative affect plays an integral role in the relationship between depressed mood and alcohol outcomes.

Alcohol Expectancies

Positive alcohol expectancies, or beliefs that drinking alcohol will lead to positive outcomes such as tension reduction and sexual enhancement, predict college student drinking (Valdivia and Stewart 2005) and problematic alcohol use (Kassel et al. 2000). Further, relative to non-distressed peers, depressed high school (Bekman et al. 2010) and college students (Park and Levenson 2002) endorse stronger positive alcohol expectancies, and positive expectancies promote drinking to cope among college student drinkers (Goldsmith et al. 2009). In a large adolescent sample, Kuntsche et al. (2010) demonstrated that alcohol motives and expectancies are distinct constructs and, of all motives, coping motives emerged as the strongest mediator in the relationship between alcohol expectancies and alcohol outcomes (e.g., heavy drinking, consequences). Collectively, it appears that positive expectancies may be an intermediate variable mediating the relationship between distress and coping, whereby greater distress is associated with higher positive expectancies. In turn, positive expectancies are related to greater use of alcohol to cope with negative internal states, which is then related to problematic drinking.

To our knowledge, no study to date has examined longitudinally how depressive symptoms at college entry predict the experience of alcohol-related negative consequences during the first year of college with a focus on college-levels factors related to alcohol risk outcomes. This gap in research represents a significant void in the literature, particularly given the high rates of depressive symptoms (Ibrahim et al. 2013) and alcohol problems (Patrick and Schulenberg 2011) among incoming college students. Gaining a better understanding of the pathways related to alcohol risk during this important developmental period may be particularly valuable for preventing more serious and potentially chronic alcohol use problems (Meier et al. 2013).

Gender

There is substantial evidence that adolescent females experience greater levels of depressive symptoms than males (e.g., Poulin et al. 2005), with some studies finding that adolescent females are over twice as likely to experience depression than males (Wade et al. 2002). In college samples, a majority of studies shows higher rates of depression among women, while others show no significant gender differences (Ibrahim et al. 2013). Although higher levels of depressive symptoms and problematic alcohol use are consistently linked irrespective of gender, college women are more likely to exhibit co-occurring depression and substance misuse (Silverman 2004). Depressed college women are more likely to experience alcohol-related negative consequences, even after controlling for drinking levels, compared with non-depressed women and depressed men (Weitzman 2004).

Findings examining the relationship between negative mood and both expectancies and coping motives as a function of gender have been inconsistent. For example, whereas some studies have shown that females drink to cope more than males (e.g., Timko 2005), others support that males are more likely to drink to cope (Park and Levenson 2002), and still others have found no gender differences (LaBrie et al. 2011). Given the substantial gender differences in mental health and alcohol behaviors but lack of consistent findings explaining these differentials, we examined gender-specific pathways in our analyses to examine potential differences that might inform the literature and need for distinct treatment approaches.

Study Aims and Objectives

The purpose of the current study was to examine the effect of depressive symptoms at college entry on alcohol expectancies, coping motives, consumption and negative consequences during the first year of college in a large multi-site sample of men and women. In order to isolate the influence of college-level variables, we controlled for race and ethnicity and pre-college levels of alcohol expectancies, coping motives, and consumption. Further, to best demonstrate the independent influence of coping drinking motives during college, we accounted for social, enhancement, and conformity drinking motives, both at pre-college and during college. Finally, given the limited and inconsistent research findings related to the effect of negative expectancies on heavy drinking—studies reveal both positive (Lee et al. 1999) and inverse (Valdivia and Stewart 2005) relationships—we included pre-college and college-level negative expectancies in the current models.

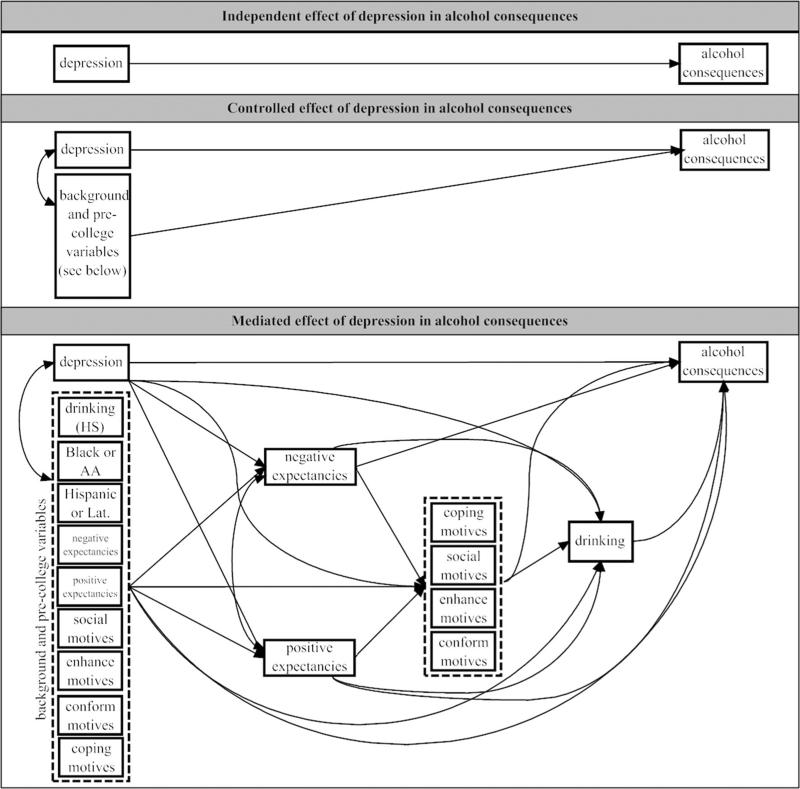

We hypothesized theoretically and empirically supported pathways of influence consistent with the stressor vulnerability model and extant research. We expected that higher levels of pre-college depressive symptoms would predict greater experience of alcohol consequences during college through greater endorsement of positive alcohol expectancies and greater coping motives for drinking during college, even after controlling for pre-college factors (see Fig. 1 for the conceptual model).

Fig. 1.

Path diagram illustrating hypothesized model

Methods

Participants

Data used in the present study were obtained from a larger longitudinal alcohol study that assessed students’ alcohol use behaviors from pre-college to senior year of college. Inclusion criteria for the parent study were: aged under 21 years, matriculating into college as a fulltime student, living on campus during their first year in college, and not an international student. Participants were recruited from three 4-year universities/colleges in the Northeastern US, including both private and public institutions. College 1 was a private institution with a student body of approximately 6000 undergraduates, College 2 was a public institution with approximately 6000 undergraduate students, and College 3 was a public institution with approximately 7000 undergraduate students.

The sample used in the current study included 614 incoming first-year college students: 367 (60 %) participants from College 1, 163 (27 %) participants from College 2, and 84 (14 %) participants from College 3. Additional participant characteristics are reported in Table 1. The current sample had a mean age of 18 years (SD = 0.5) and was 59 % female. Racial composition was: 67 % White, 9 % Asian, 6 % African American, 0.3 % Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 11 % Multiracial, 7 % Other, and 0.2 % unknown. Additionally, 7 % reported Hispanic ethnicity.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by gender

| Men (N = 253) M (SD) |

Women (N = 361) M (SD) |

Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms (T1) | 9.9 (7.4) | 11.0 (8.7) | F = 2.7, p = .10 |

| Alcohol expectancies | |||

| Positive (T1) | 2.6 (0.5) | 2.5 (0.6) | F = 1.3, p = .26 |

| Positive (T2) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.6) | F = 0.0, p = .85 |

| Negative (T1) | 2.5 (0.5) | 2.5 (0.6) | F = 1.8, p = .19 |

| Negative (T2) | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.6) | F = 0.1, p = .71 |

| Drinking motives | |||

| Coping (T1) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.7) | F = 0.4, p = .55 |

| Coping (T2) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.8 (0.8) | F = 7.3, p = .01 |

| Conformity (T1) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.5) | F = 6.4, p = .01 |

| Conformity (T2) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.6) | F = 0.5, p = .49 |

| Social (T1) | 2.9 (1.0) | 2.8 (1.1) | F = 1.6, p = .21 |

| Social (T2) | 3.1 (1.0) | 3.1 (1.1) | F = 0.0, p = .97 |

| Enhancement (T1) | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.1) | F = 0.1, p = .81 |

| Enhancement (T2) | 2.8 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.1) | F = 0.6, p = .46 |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| Number of drinks/month (high school)a (T1) | 16.7 (31.5) | 11.5 (25.4) | F = 9.5, p < .01 |

| Number of drinks/month (first year college)a (T2) | 43.8 (55.0) | 31.7 (49.9) | F = 14.9, p < .01 |

| Negative alcohol consequences (T2) | 7.8 (6.6) | 7.7 (6.8) | F = 0.0, p = .93 |

T1 Time 1, collected prior to the start of the first year of college; T2 Time 2, collected at the end of the first year of college

Log transformed value used in analytic models, including F-tests in this table

Design and Procedure

A gender-stratified random sample of incoming students that oversampled non-White students (N = 2821) was invited to participate in the larger study. Relative to the other sites, College 1 had a larger proportion of minority students, and thus more students overall were drawn from this site. Approximately 2 months before arriving on campus selected students were mailed a description of the study, informed consent form, information about how to enroll online using a unique username and password, and $5 for considering participation. For students under 18 years, parental consent was obtained. Non-responders were mailed a second packet and reminded of the study via telephone. In all, 1053 students (37 % of invited) were enrolled in the study.

Data Collection

Participants provided consent online or through the mail after which they were directed to the baseline survey, which was administered via commercial web-based survey software. Students completed the pre-college baseline (Time 1) survey between mid-July and late August; the survey was closed prior to students’ arrival on campus. At the end of the first year of college (mid-May), 928 participants (88 % of those completing the Time 1 survey) completed a second web-based survey (Time 2). In all, the final sample for the current investigation included 614 participants (66 % of those completing both Time 1 and Time 2 surveys) who met the inclusion criteria (reported drinking at least one alcoholic drink both during the year prior to college entry and during their first academic year of college). The drinking inclusion criteria was necessary because only drinkers were administered the drinking motives and alcohol consequence measures at each time point. Participants received $20 for completing the baseline survey and $25 for completing the end-of-year survey.

Measures

Demographics, depressive symptoms, and pre-college alcohol consumption, expectancies, and motives were assessed at Time 1 (pre-college survey). College alcohol expectancies, motives, consumption, and negative consequences were assessed at Time 2 (survey at end of the first year of college).

Number of Drinks

Number of drinks was the average number of drinks consumed per month in the past year (T1 pre-college) and past academic year (T2 first year of college). Visual images displayed examples of standard drinks (e.g., 12 oz. beer, five oz. wine, one shot of liquor). Participants completed the Graduated Frequency measure (Hilton 1989) that starts by asking the respondent the largest number of drinks they have consumed on any single day during the assessed time period. The measure then queries the frequency of consuming different quantities of drinks, starting with the maximum drink level and working downward. The quantities are 12 or more, 8–11, 5–7, 3–4, and 1–2 drinks. The frequency intervals are “every day or nearly every day,” “3–4 times a week,” “once or twice a week,” “1–3 times a month,” “7–11 times in the year,” “3–6 times in the year,” “twice in the year,” “once in the year,” and “never.” The number of drinks variable was derived by summing the cross products of frequency and quantity values using the midpoint of each quantity band by the midpoint of the associated frequency band, and converting that value to average drinks per month (see Greenfield and Rogers 1999 for detailed information on calculations).

Depressive Symptoms

The 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (α = .88; CES-D; Radloff 1991) measured participants’ depressive symptoms in the past week (e.g., “I had crying spells” and “I felt that everything I did was an effort”) using a four-point scale ranging from 0 [Rarely or none of the time (<1 day)] to 3 [Most or all of the time (5–7 days)]. Response options were summed (sample range 0–47).

Alcohol Expectancies

Participants’ positive and negative expectancies about alcohol consumption were assessed using the Brief Comprehensive Effects of Alcohol Scale (B-CEOA; Fromme et al. 1993; Ham et al. 2005). A total of 15 items assessed the anticipated effects of drinking on behaviors and feelings using a four-point scale ranging from 1 (Disagree) to 4 (Agree) (sample range 1–4 for all expectancy variables). Positive expectancies averaged responses to eight items [α = .86 (T1), α = .83 (T2); e.g., “I would act sociable” and “I would enjoy sex more”] and negative expectancies averaged responses to seven items [α = .75 (T1), α = .83 (T2); “I would feel clumsy” and “I would act aggressively”].

Drinking Motives

Motivations for drinking were assessed using the 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ; Cooper 1994), a well-validated measure of drinking motives in college student populations (Cooper 1994; MacLean and Lecci 2000). Respondents were asked, “Thinking of the times you drank in the past 30 days, how often you would say that you drank for the following reasons?” Responses were measured on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always). Four subscales were assessed at each time point using mean composites (sample range 1–5 for all motive subscales): Coping [α = .85 (T1), α = .83 (T2); e.g., “To forget your worries”], Conformity [α = .89 (T1), α = .88 (T2); e.g., “To be liked”], Social [α = .81 (T1), α = .84 (T2); e.g., “Because it helps you enjoy a party”], and Enhancement [α = .88 (T1), α = .91 (T2); e.g., “Because it's exciting”].

Alcohol-Related Negative Consequences

The 27-item Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (α = .81; YAAPST; Hurlbut and Sher 1992) was used to assess the frequency of alcohol-related negative consequences experienced during the first year of college (e.g., “Have you not gone to work or missed classes at school because of drinking, a hangover, or an illness caused by drinking?”). Response options were dichotomized and summed to yield a total score ranging from 0 to 27.

Data Preparation

Prior to analyses, we explored the distributional properties of all study variables. Number of drinks consumed per month during the first year of college was positively skewed and therefore log-transformed for analyses (Cohen et al. 2003). Following transformations, none of the skewness or kurtosis levels exceeded an absolute value of .77. For ease of interpretation, the non-transformed values for number of drinks in college are reported in Table 1.

Analytic Plan

We addressed our analytic goals using path analysis. The hypothesized model (see Fig. 1) examined depressive symptoms at college entrance (Time 1) as a predictor of alcohol-related negative consequences experienced during the first year of college (Time 2), controlling for pre-college drinking levels. Putative mediators of the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol consequences were specified as follows: depressive symptoms predicted both positive and negative alcohol expectancies, which in turn predicted drinking motives, average number of drinks per month and alcohol consequences during the first year of college. Drinking to cope was specified to predict drinking and consequences, and drinking was specified to predict consequences. We used Stata software (version 13.1, StataCorp, College Station, TX) for descriptive analyses and Mplus software (version 7.3, Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA) to estimate parameters for the path analysis. We estimated model parameters for the path model using a multiple group model, which estimates parameters in men and women at the same time and allows for tests of equivalence of parameters across groups. Parameter estimates were obtained with maximum likelihood methods. The final model was trimmed of paths that were not significant at a >10 % level using a backwards stepwise procedure. Confidence intervals were obtained with biased corrected bootstrap procedures.

Results

Comparison of Means by Gender

In this sample, 18 % (n = 45) of males and 20 % (n = 72) of females scored above a commonly used threshold to define clinically significant depressive symptoms (i.e., 16 or more on the CES-D). These prevalence rates are lower than the rates of at least mild depressive symptoms found in a recent systematic reviews (31 % in Ibrahim et al. 2013), but higher than rates of diagnosed depression reported in large representative samples of US college students (ACHA 2013). Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of studied variables as a function of gender. Overall, women reported lower levels of drinking, both pre-college (p < .01) and during college (p < .01), higher coping motives for drinking during college (p = .01), and lower conformity motives for drinking pre-college (p = .01) compared to men. No other measures differed significantly by gender, including depressive symptoms at college entrance (p = .10) and experience of alcohol consequences during college (p = .93).

Path Analysis

The results of the path analysis are summarized in Table 2. The full set of parameter estimates from the final fitted model are reported in Table 3. In a simple bivariable linear regression, the independent effect of depressive symptoms predicting alcohol-related negative consequences was significant for women (standardized regression coefficient, β = 0.13, p = .01) and of a similar magnitude in men (β = 0.12, p = .09). Given the similar estimates, differential significance levels are due to the smaller sample size for men. After controlling for T1 factors, including race/ethnicity, and pre-college positive and negative alcohol expectancies, drinking motives, and levels of drinking (controlled model in Table 2), the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol consequences was attenuated in both men and women, but more so among women. In the mediated model (which represents a fitted form of the hypothesized model summarized in Fig. 1) among men, the original bivariable association of depressive symptoms and consequences was retained and emerged as statistically significant, with a total effect of (β = 0.14, p < .001). Among women, the mediated total effect (β = 0.05, p = .22) is shown as more of an indirect (β = 0.03, p = .13) effect than a direct effect (β = 0.02, p = .66), but so close to zero as to be essentially ignorable. Among men, the bivariable effect between depressive symptoms and alcohol consequences in the mediated model is independent of other factors in our model (i.e., T1 and T2 alcohol expectancies, motives, and drinking). In contrast, among women, the bivariable association of depression and consequences is largely a reflection of other factors in the model.

Table 2.

Summary of bivariable, controlled, and mediated models: regression of consequences on depressive symptoms

| Model | Men |

Women |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | P | Est | P | |

| Bivariable | 0.12 | .09 | 0.13 | .01 |

| Controlled | 0.09 | .13 | 0.04 | .35 |

| Mediated | ||||

| Total | 0.14 | <.001 | 0.05 | .22 |

| Direct | 0.15 | <.001 | 0.02 | .66 |

| Indirect | –0.01 | .14 | 0.03 | .13 |

Parameter estimates are regression (path) estimates from a multiple (sex) group model. All variables have been standardized to the between groups mean and standard deviation or centered at the between groups mean if dichotomous (race/ethnicity). P values refer to the test that the parameter is significantly non-zero. The bivariable model refers to a multiple (sex) group regression of alcohol use consequences on depressive symptoms. The controlled model refers to the regression of consequences on depressive symptoms adjusting for all other T1 variables (see Table 1). The mediated model is reported in full in Table 3 and refers to the regression of consequences on depressive symptoms, controlling for other T1 variables, and allowing for possible mediation via other T2 variables reflecting the freshman year. This full model has been trimmed of parameters that were not significant (within groups) at the α = .10 level in a backwards stepwise fashion

Table 3.

Mediated model parameter estimates

| Model parameter | Men |

Women |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. (CI) | P | Est. (CI) | P | |

| Alcohol consequences (college T2)a | ||||

| On depressive symptoms (T2) | 0.15 (0.07, 0.24) | <.001 | 0.02 (–0.06, 0.09) | .66 |

| On number of drinks/month (T2) | 0.43 (0.31, 0.56) | <.001 | 0.55 (0.46, 0.64) | <.001 |

| On coping motives (T2) | 0 | – | 0.23 (0.14, 0.33) | <.001 |

| On social motives (T2) | 0.14 (0.03, 0.25) | .01 | 0 | – |

| On enhancement motives (T1) | 0 | – | 0.19 (0.10, 0.28) | <.001 |

| Number of drinks/month (college T2)b | ||||

| On coping motives (T2) | 0 | – | 0.10 (0.02, 0.19) | .02 |

| On social motives (T2) | 0.13 (0.00, 0.27) | .07 | 0.11 (–0.02, 0.22) | .07 |

| On enhancement motives (T2) | 0.31 (0.18, 0.45) | <.001 | 0.26 (0.14, 0.38) | <.001 |

| On conformity motives (T2) | 0 | – | –0.09 (–0.17, 0.00) | .04 |

| On positive expectancies (T2) | 0.14 (0.02, 0.26) | .02 | 0 | – |

| On number of drinks/month (T1) | 0.30 (0.22, 0.39) | <.001 | 0.51 (0.41, 0.59) | <.001 |

| On conformity motives (T1) | –0.14 (–0.23, –0.06) | .01 | 0 | – |

| On positive expectancies (T1) | 0.12 (–0.00, 0.25) | .07 | 0 | – |

| Coping motives for drinking (college T2)c | ||||

| On depressive symptoms (T1) | 0 | – | 0.12 (0.00, 0.22) | .03 |

| With social motives (T2) | 0.12 (0.06, 0.19) | <.001 | 0.28 (0.20, 0.37) | <.001 |

| With enhancement motives (T2) | 0.12 (0.07, 0.19) | <.001 | 0.25 (0.16, 0.34) | <.001 |

| With conformity motives (T2) | 0.17 (0.07, 0.29) | .01 | 0.29 (0.19, 0.40) | <.001 |

| On positive expectancies (T2) | 0.36 (0.16, 0.43) | <.001 | 0.35 (0.23, 0.48) | <.001 |

| On coping motives (T1) | 0.30 (0.16, 0.43) | <.001 | 0.35 (0.23, 0.48) | <.001 |

| On social motives (T1) | 0 | – | –0.17 (–0.29, –0.06) | .01 |

| On enhancement motives (T1) | –0.09 (–0.20, –0.01) | <.001 | 0 | – |

| On conformity motives (T1) | 0.13 (0.03, 0.24) | .01 | 0 | – |

| On positive expectancies (T1) | –0.14 (–0.27, –0.01) | .04 | –0.13 (–0.24, –0.01) | .03 |

| Social motives for drinking (college T2)d | ||||

| On depressive symptoms (T1) | 0 | – | –0.08 (–0.15, –0.00) | .04 |

| With enhancement motives (T2) | 0.30 (0.23, 0.38) | <.001 | 0.39 (0.32, 0.48) | <.001 |

| With conformity motives (T2) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.14) | .01 | 0.22 (0.16, 0.30) | <.001 |

| On negative expectancies (T2) | 0.10 (0.01, 0.20) | .03 | 0 | – |

| On positive expectancies (T2) | 0.44 (0.33, 0.55) | <.001 | 0.42 (0.31, 0.51) | <.001 |

| On coping motives (T1) | –0.12 (–0.23, –0.02) | .02 | 0 | – |

| On social motives (T1) | 0.41 (0.31, 0.50) | <.001 | 0.44 (0.37, 0.53) | <.001 |

| On positive expectancies (T1) | –0.15 (–0.27, –0.04) | .01 | –0.11 (–0.20, –0.01) | .03 |

| On Black or African-American (vs. others) | 0 | – | 0.58 (0.14, 1.04) | .01 |

| Enhancement motives (college T2)e | ||||

| On depressive symptoms (T1) | –0.07 (–0.15, 0.00) | .06 | –0.08 (–0.16, 0.01) | .07 |

| With conformity motives (T2) | 0 | – | 0.19 (0.13, 0.27) | <.001 |

| On positive expectancies (T2) | 0.43 (0.33, 0.52) | <.001 | 0.41 (0.29, 0.50) | <.001 |

| On coping motives (T1) | –0.15 (–0.25, –0.05) | .01 | 0 | – |

| On enhancement motives (T1) | 0.52 (0.44, 0.60) | <.001 | 0.48 (0.41, 0.56) | <.001 |

| On positive expectancies (T1) | –0.12 (–0.24, 0.01) | .09 | –0.11 (–0.22, –0.11) | .03 |

| On Hispanic or Latino (vs. others) | 0 | – | –0.24 (–0.49, 0.02) | .06 |

| Conformity motives for drinking (college T2)f | ||||

| On negative expectancies (T2) | 0.18 (0.07, 0.31) | .01 | 0 | – |

| On positive expectancies (T2) | 0.24 (0.11, 0.38) | <.001 | 0.25 (0.11, 0.37) | <.001 |

| On number of drinks/month (T1) | 0 | – | –0.11 (–0.20, –0.01) | .03 |

| On conformity motives (T1) | 0.45 (0.33, 0.55) | <.001 | 0.47 (0.36, 0.59) | <.001 |

| On positive expectancies (T1) | –.20 (–0.37, –0.05) | .01 | –0.10 (–0.20, 0.01) | .06 |

| On Hispanic or Latino (vs. others) | 0 | – | –0.24 (–0.49, 0.00) | .06 |

| Negative expectancies (college T2)g | ||||

| On depressive symptoms (T1) | 0 | – | 0.07 (–0.00, 0.14) | .07 |

| With positive expectancies (T2) | 0.47 (0.31, 0.64) | <.001 | 0.40 (0.30, 0.51) | <.001 |

| On social motives for drinking (T1) | 0 | – | 0.20 (0.10, 0.28) | <.001 |

| On enhancement motives (T1) | 0 | – | –0.15 (–0.24, –0.06) | <.001 |

| On conformity motives (T1) | 0.11 (0.04, 0.19) | .01 | 0 | – |

| On negative expectancies (T1) | 0.38 (0.26, 0.49) | <.001 | 0.53 (0.44, 0.61) | <.001 |

| On Hispanic or Latino (vs. others) | –0.63 (–1.32, –0.03) | .05 | –0.21 (–0.43, 0.04) | .08 |

| Positive expectancies (college T2)h | ||||

| On number of drinks/month (T1) | –0.09 (–0.20, 0.01) | .08 | 0 | – |

| On social motives for drinking (T1) | 0.18 (0.05, 0.30) | .01 | 0.18 (0.08, 0.27) | <.001 |

| On negative expectancies (T1) | 0 | – | 0.20 (0.10, 0.30) | <.001 |

| On positive expectancies (T1) | 0.31 (0.18, 0.43) | <.001 | 0.29 (0.18, 0.37) | <.001 |

Parameter estimates are regression (path) estimates from a multiple (sex) group model. All variables have been standardized to the between groups mean and standard deviation or centered at the between groups mean if dichotomous (race/ethnicity). Confidence intervals are estimated using bias corrected bootstrap resampling and Mplus software (version 7.3, Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA). P values refer to the test that the parameter is significantly non-zero. The full model has been trimmed of parameters that were not significant (within groups) at the α = .10 level in a backwards stepwise fashion. The following measures were removed in designated models, as follows: depressive symptomsbcfh, number of drinks at T1cdeg, social motives at T1abef, enhancement motives at T1bdfh and T2a, conformity motives at T1adeh and T2a, coping motives at T1abfgh, negative expectancies at T1a–f and T2abce, positive expectancies at T1ag and T2a, racea–c,e–h, ethnicitya–d,h

The full model results are shown in Table 3. The effect of depressive symptoms at college entry on the experience of alcohol consequences during college was principally attributable to coping motives at T1 (data not shown). However, among women there is not a direct relationship between T1 coping motives and college consequences. The (nonsignificant) path that links depressive symptoms at T1 to consequences at T2 (top row, Table 3) involves coping motives assessed at T1 as well as the dependency of coping motives assessed at T1 on coping motives assessed at T2 (β = 0.35, p < .001). In turn, coping motives assessed at T2 was associated with alcohol consequences assessed at T2 (β = 0.23, p < .001).

In the full model, among men, depressive symptoms at college entry independently and directly predicted greater levels of alcohol consequences. Depressed mood at matriculation was not predictive of college drinking or alcohol expectancies for either men or women. Additional significant paths to T2 alcohol consequences include alcohol consumption during college for both men (β = 0.43, p < .001) and women (β = 0.55, p < .001). Whereas college coping motives (β = 0.23, p < .001) was associated with college alcohol consequences for women, college social motives was associated with consequences for men only (β = 0.14, p = .01). Other significant indirect paths among women included depressive symptoms on drinking to cope in college (β = 0.12, p = .03) and drinking to cope in college on college drinking (β = 0.10, p = .02). Pre-college drinking and college enhancement motives for drinking were related to greater levels of drinking in college for both men and women (ps < .001). Pre-college conformity motives was inversely associated (β = −0.14, p = .01) and positive expectancies was positively associated (β = 0.14, p = .02) with college drinking in men only. Among both men and women, all college drinking motives significantly intercorrelated (ps < .001), as did each motive subscale at T1 and T2 (ps < .001). In addition, in females, pre-college social motives for drinking predicted lower drinking to cope in college (β = −0.17, p = .01). Positive alcohol expectancies correlated with negative expectancies (ps < .001) and greater endorsement of each drinking motive subscale (ps < .001) during college; in contrast, pre-college positive expectancies tended to predict lower levels of drinking motives. Overall, model paths did not differ by race or ethnicity.

Discussion

The ages of 18–20 years are associated with peak lifetime rates of alcohol dependence (Grant et al. 2004) and transitions to college are marked by sharp increases in heavy drinking and alcohol-related consequences (Patrick and Schulenberg 2011). Although students matriculating into college with preexisting depressive symptoms appear to face particularly high risks for experiencing alcohol consequences and developing persistent problematic drinking behaviors (Meier et al. 2013), no longitudinal studies to date have examined potential pathways through which depressive symptoms at college entry predict alcohol-related negative consequences during the first year of college for men and women. Grounded in theory and empirical research, we hypothesized that depressive symptoms would be predictive of alcohol risk through the putative mechanisms of positive alcohol expectancies, drinking to cope with negative affect, and alcohol consumption in a large, multisite sample of incoming first-year college students. In order to isolate the effects of our primary mechanisms, we also controlled for race and ethnicity, pre-college factors (alcohol expectancies, drinking motives, and alcohol consumption), and other motives for drinking during college. In the current study, we found that among females, this pathway was primarily explained by increased endorsement of drinking to cope with negative affect, both prior to and during college. In contrast, although males were found to matriculate into college with fairly similar levels of depressive symptoms as females, we were not able to identify pathways of risk in the current model.

In partial support of our hypotheses, drinking to cope was an important factor linking depressive affect with prospective alcohol risk in females. However, the path that linked depressive symptoms to alcohol consequences during college was attributable to the relationship between pre-college (T1) drinking to cope and college (T2) drinking to cope, which in turn predicted alcohol consequences during college (T2). In contrast, among males, the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol consequences in college was independent of (i.e., not explained by) pre-college and college factors in the model. These gender-specific pathways support prior research demonstrating that college women are more susceptible than men to risky alcohol outcomes due to drinking to cope with negative affective states (Bischof et al. 2005; Park et al. 2004; Timko 2005).

An unexpected finding was that positive expectancies did not emerge as a significant mechanism through which depressive affect predicted alcohol risk in women. In fact, depressive symptoms did not predict expectancies in college for either men or women, although these variables were bivariately correlated in this sample (r = .09, p = .02; correlation matrix not presented). Positive expectancies were also indirectly related to alcohol consequences via increased coping motives in women, and by way of increased social motives and drinking in men. Overall, these findings indicate that more research is needed to disentangle the role of expectancies as it relates to depressive affect, drinking motives, and alcohol risk.

Female Model

The findings related to women are consistent with a social learning theoretical framework and empirical research that link depressive symptoms with problematic alcohol use through drinking to cope with negative affect (Cooper et al. 1995). After accounting for other pre-college and college factors, depressive status predicted drinking to cope in college, which was associated with greater alcohol consumption and consequences. The strongest path, however, was related to depressed women's reliance on drinking to cope prior to college, which was associated with continued coping motivated drinking behaviors, and in turn the experience of related negative consequences, during college. Our finding that much of women's reliance on drinking to cope with negative affect in college appears to originate from drinking-related coping behaviors that develop prior to matriculation is consistent with research demonstrating that risky drinking behaviors in college may, in part, be a continuation of risky behaviors in high school (Kenney et al. 2010).

Male Model

In contrast to the well-established gender gap that indicates substantially greater depressive symptoms in female than male adolescents (Poulin et al. 2005), in the current sample, there was a small to trivial effect size for sex differences in depressive symptoms (d = .13). Although men arrived on campus with fairly similar levels of depressive symptoms as women and men's depressive symptoms predicted prospective alcohol risk, we were not able to identify pathways of risk in the current model. Although social motives for drinking and typical drinking during college were directly associated with greater experience of alcohol consequences, these constructs were not influenced by depressive symptoms at college entry. According to theories of masculinity, norms that guide men's drinking behaviors include risk-taking, sexual attainment, aggression, dominance, and pursuit of social status (Mahalik et al. 2003). Indeed, untested factors such as risk-taking behaviors and peer normative beliefs or relationship quality may be more salient mediators in depressed men's experience of risky drinking. Research that explores alternative models that account for potential intervening risk factors in this relationship is warranted.

Altogether, these findings demonstrate that college transitions may be particularly risky for women who drink to cope with stressful events or aversive states (Park et al. 2004). Perhaps attributed to heightened levels of interpersonal distress adjusting to college environments relative to male peers (Enochs and Roland 2006), the transition from high school to college presents a uniquely risky period for women with respect to alcohol behaviors and outcomes (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse 2003). In the current sample, women drank significantly less than men overall, but experienced similar levels of alcohol consequences. This may be explained in part by inherent physiological gender differences that put women at greater risk for rapid intoxication and a telescoped development of alcohol dependency (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse 2003). However, in the present study, drinking to cope was associated with alcohol consequences, even after controlling for college drinking, therefore highlighting the enhanced risk associated with the maladaptive practice of consuming alcohol as a means to alleviate negative affect (Kuntsche et al. 2007).

Study Implications and Directions for Future Research

Given the prevalence of heightened depressive symptoms—one in five students in this sample met the criteria for clinically significant depressive symptoms—and risk for alcohol consequences during the first year of college, collaborative harm reduction efforts among campus service centers (e.g., counseling centers, health centers, residential life) are needed to promote the psychosocial developmental needs of students. Studies support that developing students’ wellness and stress management skills helps them adapt effectively to college life (Conley et al. 2013; Shapiro et al. 2011). Moreover, training residential directors to identify students in need and screening students presenting at campus counseling or health centers may be important as students are unlikely to seek professional assistance for depressed mood or alcohol problems (Cellucci et al. 2006; Eisenberg et al. 2011; Wu and Ringwalt 2006). Counselors and medical practitioners could be trained to provide alcohol-specific counseling or brief interventions designed to teach students how to drink more safely or avoid risky drinking situations.

Identifying drinking to cope (both pre-college and college) as the primary pathway through which at-risk college women with depressive symptoms experienced alcohol-related consequences in college offers insights for administrators and mental health practitioners interested in reducing alcohol-related harm and enhancing women's overall well-being. Early interventions targeted at depressed college women that address coping deficits and motivations for drinking (e.g., coping skills training; Litt et al. 2009; Monti et al. 1989) may be particularly effective. Such modalities may interrupt pathways that lead to alcohol risk by providing students with realistic expectations of drinking and helpful tools for establishing effective coping strategies and non-drinking alternatives to better manage negative affect. For example, Hansson et al. (2007) found that a combined alcohol and coping skills training intervention was more effective in reducing college students’ alcohol problems across 2 years than either an alcohol intervention alone. However, this approach has been underutilized with college students. Alcohol interventions that have effectively incorporated coping skills training to reduce drinking and problems among adolescents (Cornelius et al. 2011) and adults (e.g., Baker et al. 2013; Monti et al. 1989) with co-occurring depression and alcohol problems may be potentially modifiable for use in college student populations.

Limitations

The measures used in the current study were based on retrospective self-reports that, despite assurances of anonymity, may introduce response bias. Particularly with respect to the gender-specific findings, women may be more willing to self-disclose information about their emotional state and motivations for drinking than men. Second, alcohol expectancies, motives, and alcohol outcomes during college were assessed at the same time point, which limits interpretability of causal processes. Third, measurement timeframes used in the current study were variable: past week depressive symptoms, general alcohol expectancies, past month motives, and past year (or academic year) drinking outcomes. Although we used well-validated measures with the intention of accurately capturing participants’ beliefs and behaviors (e.g., recall, sensitivity to reporting), the conclusions drawn from these findings should be qualified by differential assessment periods. Fourth, the regional (Northeastern) sample used in the current study includes only students reporting drinking at least one drink in the year prior to college and during the first year in college. Although this does not constitute a particularly high-risk participant pool, it nonetheless limits the external validity of the findings. Longitudinal research that examines these factors in a sample more generalizable to the broader population of US college students is needed. Finally, our measure of alcohol consumption is limited in that it calculates the total average number of drinks consumed per month using reported intervals of drinking quantity (e.g., 3–4 drinks) and frequency (e.g., drank 1–2 times a week), and thus does not provide information on how many drinks were consumed per drinking occasion. Calculating student drinkers’ blood alcohol content (BAC) with event-level assessment or measures such as the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al. 1985) may more accurately assess how levels of intoxication are related to risky outcomes.

Conclusion

Despite strong theoretical and empirical support for a framework linking depressive symptoms and alcohol risk via expectancy and coping-related pathways, this was the first study to prospectively examine this model in a large sample of adolescents during the high-risk developmental transition to college. Our findings inform potential intervention approaches for depressed women and call for research that identifies the putative mediators in the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol consequences in adolescent males. Research that builds on the present findings to further explicate the gender-specific mechanisms influencing depressed students’ prospective alcohol-related risks is essential for designing tailored early harm reduction treatments.

Acknowledgments

Shannon Kenney's contribution to this article was supported by Grant Number T32 AA007459 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health. Richard Jones’ contributions were supported by the Quantitative Sciences Program of the Brown University Warren Alpert Medical School Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Neurology, and the Norman Prince Neurosciences Institute of Rhode Island Hospital. The data were collected under Grant R01 AA13970 awarded to Nancy Barnett.

Biography

Shannon R. Kenney, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies in the School of Public Health at Brown University. Dr. Kenney received her doctorate in Sociology from Brown University. Her major research interests include the etiology, prevention, and treatment of alcohol use disorders in adolescents and young adults, particularly with respect to co-occurring health risk behaviors, such as mental health disorders and sexual risk behaviors.

Richard N. Jones, Sc.D., is an epidemiologist and methodologist. He directs the Program for Quantitative Science in the Departments of Psychiatry and Human Behavior and Neurology at Brown University Warren Alpert Medical School. Dr. Jones received his doctorate in Mental Health from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. His primary research interests include psychiatric epidemiology and aging and cognition.

Nancy P. Barnett, Ph.D., is a professor of research in the Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences in the School of Public Health at Brown University. Dr. Barnett received her doctorate in Clinical Psychology from the University of Washington. Her primary area of interest is in developing and testing brief interventions for substance use among adolescents and young adults.

Footnotes

Author contributions Each author made a substantial contribution to the current manuscript. Authors have given approval for the final version to be submitted/published and take public responsibility for their contributions and the manuscript as a whole. Specifically, S.K. conceived of the study and conceptualized the design; conducted preliminary analyses; performed the literature review; drafted the “Introduction”, “Measures”, and “Discussion” sections; and revised the manuscript in its entirety. R.J. worked with S.R. and N.B. to further conceptualize methods, conducted advanced statistical analyses, and wrote the “Methods” and “Results” sections. N.B. was PI of the original study from which data were collected, was involved in all aspects of the design of the current paper, and coordinated revisions to several drafts of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest The authors report no conflict of interests.

References

- ACHA. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Reference group undergraduates executive summary, spring 2013. American College Health Association; Hanover, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Baker AL, Kavanagh DJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Hunt SA, Lewin TJ, Carr VJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of MICBT for co-existing alcohol misuse and depression: Outcomes to 36-months. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.10.001. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AL, Kavanagh DJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Hunt SA, Lewin TJ, Carr VJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive–behavioural therapy for coexisting depression and alcohol problems: Short-term outcome. Addiction. 2010;105(1):87–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02757.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AL, Thornton LK, Hiles S, Hides L, Lubman DI. Psychological interventions for alcohol misuse among people with co-occurring depression or anxiety disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;139(3):217–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.004. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekman NM, Cummins K, Brown SA. Affective and personality risk and cognitive mediators of initial adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71(4):570–580. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen-Cico D. Patterns of substance abuse and attrition among first-year students. Journal of the First-Year Experience & Students in Transition. 2000;12(1):61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bischof G, Rumpf HJ, Meyer C, Hapke U, John U. Gender differences in temptation to drink, self-efficacy to abstain and coping behavior in treated alcohol-dependent individuals: Controlling for severity of dependence. Addiction Research & Theory. 2005;13(2):129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Liu S-M, et al. Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers: Results from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1429–1437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs J, Schulenberg J, Hingson R, Swartzwelder S, et al. A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16–20 years of age. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S290–S310. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cellucci T, Krogh J, Vik P. Help seeking for alcohol problems in a college population. The Journal of General Psychology. 2006;133(4):421–433. doi: 10.3200/GENP.133.4.421-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley CS, Travers LV, Bryant FB. Promoting psychosocial adjustment and stress management in first-year college students: The benefits of engagement in a psychosocial wellness seminar. Journal of American College Health. 2013;61(2):75–86. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.754757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Pinquart M, Gamble SA. Meta-analysis of depression and substance use among individuals with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37(2):127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117–128. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(5):990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Douaihy A, Bukstein OG, Daley DC, Wood SD, Kelly TM, et al. Evaluation of cognitive behavioral therapy/motivational enhancement therapy (CBT/MET) in a treatment trial of comorbid MDD/AUD adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(8):843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.016. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagan K, Stolzenberg EB, Ramirez JJ, Aragon MC, Suchard MR, Hurtado S. The American freshman: National norms fall 2014. Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA; Los Angeles: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Hunt J, Speer N, Zivin K. Mental health service utilization among college students in the United States. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2011;199(5):301–308. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182175123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enochs WK, Roland CB. Social adjustment of college freshmen: The importance of gender and living environment. College Student Journal. 2006;40(1):63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Evans DM, Dunn NJ. Alcohol expectancies, coping responses and self-efficacy judgments: A replication and extension of Cooper et al.'s 1988 study in a college sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56(2):186–193. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Stroot EA, Kaplan D. Comprehensive effects of alcohol: Development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5(1):19–26. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.5.1.19. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher RP. Thirty years of the National Survey of Counseling Center Directors: A personal account. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 2012;26(3):172–184. doi:10.1080/87568225.2012.685852. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith AA, Tran GQ, Smith JP, Howe SR. Alcohol expectancies and drinking motives in college drinkers: Mediating effects on the relationship between generalized anxiety and heavy drinking in negative-affect situations. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(6–7):505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.01.003. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009. 01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74(3):223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Rogers J. Who drinks the most of all alcohol in the US? The policy implications. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(1):78–89. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gress-Smith JL, Roubinov DS, Andreotti C, Compas BE, Luecken LJ. Prevalence, severity and risk factors for depressive symptoms and insomnia in college undergraduates. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress. 2015;31(1):63–70. doi: 10.1002/smi.2509. doi:10.1002/smi.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham L, Stewart S, Norton P, Hope D. Psychometric assessment of the comprehensive effects of alcohol questionnaire: Comparing a brief version to the original full scale. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment. 2005;27(3):141–158. doi:10.1007/s10862-005-0631-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Zamboanga BL, Bacon AK, Garcia TA. Drinking motives as mediators of social anxiety and hazardous drinking among college students. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2009;38(3):133–145. doi: 10.1080/16506070802610889. doi:10.1080/16506070802610889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson H, Rundberg J, Zetterlind U, Johnsson KO, Berglund M. Two-year outcome of an intervention program for university students who have parents with alcohol problems: A randomized controlled trial. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(11):1927–1933. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Wechsler H, Muthén BO. Alcohol-related aggression and drinking at off-campus parties and bars: A national study of current drinkers in college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(5):704–711. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasking P, Lyvers M, Carlopio C. The relationship between coping strategies, alcohol expectancies, drinking motives and drinking behaviour. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(5):479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.014. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton ME. A comparison of a prospective diary and two summary recall techniques for recording alcohol consumption. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84(9):1085–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health. 1992;41(2):49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hysenbegasi A, Hass SL, Rowland CR. The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2005;8(3):145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2013;47(3):391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Jackson SI, Unrod M. Generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation and problem drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(2):332–340. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, Hummer JF, Labrie JW. An examination of prepartying and drinking game playing during high school and their impact on alcohol-related risk upon entrance into college (English). Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(9):999–1011. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9473-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, LaBrie JW. Use of protective behavioral strategies and reduced alcohol risk: Examining the moderating effects of mental health, gender, and race. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(4):997–1009. doi: 10.1037/a0033262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, Meehan BT, Trim RS, Chassin L. Marker or mediator? The effects of adolescent substance use on young adult educational attainment. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2006;101(12):1730–1740. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Engels R, Gmel G. Drinking motives as mediators of the link between alcohol expectancies and alcohol use among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(1):76–85. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(10):1844–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Wiers RW, Janssen T, Gmel G. Same wording, distinct concepts? Testing differences between expectancies and motives in a mediation model of alcohol outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18(5):436–444. doi: 10.1037/a0019724. doi:10.1037/a0019724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo P-H, Gardner CO, Kendler KS, Prescott CA. The temporal relationship of the onsets of alcohol dependence and major depression: Using a genetically informative study design. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(8):1153–1162. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, McCarthy DM, Coe MT, Brown SA. Transition to independent living and substance involvement of treated and high risk youth. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2004;13(3):85–100. doi:10.1300/J029v13n03_05. [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Lac A, Kenney SR, Mirza T. Protective behavioral strategies mediate the effect of drinking motives on alcohol use among heavy drinking college students: Gender and race differences. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(4):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NK, Greely J, Oei TPS. The relationship of positive and negative alcohol expectancies to patterns of consumption of alcohol in social drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24(3):359–369. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Hove MC, Whiteside U, Lee CM, Kirkeby BS, Oster-Aaland L, et al. Fitting in and feeling fine: Conformity and coping motives as mediators of the relationship between social anxiety and problematic drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(1):58–67. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.58. doi:10.1037/0893-164x.22.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Kabela-Cormier E. Individualized assessment and treatment program for alcohol dependence: Results of an initial study to train coping skills. Addiction. 2009;104(11):1837–1848. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02693.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Do changes in drinking motives mediate the relation between personality change and “maturing out” of problem drinking? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(1):93–105. doi: 10.1037/a0017512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean MG, Lecci L. A comparison of models of drinking motives in a university sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14(1):83–87. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Locke BD, Ludlow LH, Diemer MA, Scott RPJ, Gottfried M, et al. Development of the conformity to masculine norms inventory. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2003;4(1):3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Martin JL, Hatchett ES, Fowler RM, Fleming KM, Karakashian MA, et al. Protective behavioral strategies and the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008a;55(4):535–541. doi: 10.1037/a0013588. doi:10.1037/a0013588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Oster-Aaland L, Larimer ME. The roles of negative affect and coping motives in the relationship between alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008b;69(3):412–419. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier MH, Caspi A, Houts R, Slutske WS, Harrington H, Jackson KM, et al. Prospective developmental subtypes of alcohol dependence from age 18 to 32 years: Implications for nosology, etiology, and intervention. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25(3):785–800. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000175. doi:10.1017/S0954579413000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(4):705–711. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. doi:10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Abrams DB, Kadden RM, Cooney NL. Treating alcohol dependence: A coping skills training guide. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University . The formative years: Pathways to substance abuse among girls and young women ages 8–22. Columbia University; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), Task Force of the National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . A call to action: Changing the culture of drinking at US colleges. National Institutes of Health, US. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS); Bethesda, MD: 2002. (NIH publication no. 02–5010) [Google Scholar]

- O'Hare T, Shen C. Substance use motives and severe mental illness. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2012;8(3):171–179. doi:10. 1080/15504263.2012.696184. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Armeli S, Tennen H. The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(1):126–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Levenson MR. Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems and coping processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(4):486–497. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. How trajectories of reasons for alcohol use relate to trajectories of binge drinking: National panel data spanning late adolescence to early adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(2):311–317. doi: 10.1037/a0021939. doi:10.1037/a0021939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin C, Hand D, Boudreau B, Santor D. Gender differences in the association between substance use and elevated depressive symptoms in a general adolescent population. Addiction. 2005;100(4):525–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01033.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005. 01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reetz DR, Barr V, Krylowicz B. The association for university and college counseling center directors annual survey. 2013 Retrieved from http://files.cmcglobal.com/AUCCCD_Mono graph_Public_2013.pdf.

- Rice KG, Van Arsdale AC. Perfectionism, perceived stress, drinking to cope, and alcohol-related problems among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57(4):439–450. doi:10.1037/a0020221. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Brown KW, Astin J. Toward the integration of meditation into higher education: A review of research evidence. Teachers College Record. 2011;113(3):493–528. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MM. College student suicide prevention: Background and blueprint for action. Student Health Spectrum. 2004:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Morris E, Mellings T, Komar J. Relations of social anxiety variables to drinking motives, drinking quantity and frequency, and alcohol-related problems in undergraduates. Journal of Mental Health. 2006;15(6):671–682. doi:10.1080/09638230600998904. [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen J, Conway KP, Degenhardt L, Glantz M, Jin R, Merikangas KR, et al. Mental disorders as risk factors for substance use, abuse and dependence: Results from the 10-year follow-up of the National Comorbidity Survey. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2010;105(6):1117–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02902.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton LK, Baker AL, Johnson MP, Kay-Lambkin F, Lewin TJ. Reasons for substance use among people with psychotic disorders: Method triangulation approach. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(2):279–288. doi: 10.1037/a0026469. doi:10.1037/a0026469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C. The 8-year course of alcohol abuse: Gender differences in social context and coping. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(4):612–621. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000158832.07705.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia I, Stewart SH. Further examination of the psychometric properties of the comprehensive effects of alcohol questionnaire. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2005;34(1):22–33. doi: 10.1080/16506070410001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade TJ, Cairney J, Pevalin DJ. Emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence: National panel results from three countries. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(2):190–198. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00013. doi:10.1097/00004583-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER. Poor mental health, depression, and associations with alcohol consumption, harm, and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192(4):269–277. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120885.17362.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-T, Ringwalt CL. Use of alcohol treatment and mental health services among adolescents with alcohol use disorders. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC) 2006;57(1):84–92. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]