Abstract

Background

Both endometrial cancer and postmenopausal breast cancer risk are increased by obesity and higher endogenous estrogen levels. While aromatase inhibitors reduce breast cancer incidence, their influence on endometrial cancer is uncertain.

Methods

We addressed this issue in a cohort of 17,064 women diagnosed with hormone receptor positive breast cancer in an integrated group practice health plan. Information on demographics, comorbidities and adjuvant endocrine therapy use was available from electronic medical and pharmacy records, respectively. Endometrial cancer information was obtained from the health plan’s SEER-affiliated tumor registry and rates were compared across endocrine therapy groups (aromatase inhibitor [n=5,303], tamoxifen [n=5155], switchers [both n=3787] or none [n=2819] using multi-variable adjusted Cox proportional hazard models.

Results

Endometrial cancer incidence was a statistically significant, 48% lower in the aromatase inhibitor versus tamoxifen group (HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31–0.87, P=0.01). Endometrial cancer incidence was 29% lower in the aromatase inhibitor versus no endocrine therapy group (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.37–1.35, P=0.30) and was 33% lower in the aromatase inhibitor versus tamoxifen group (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.42–1.06, P=0.08), but neither difference was statistically significant. Associations were stronger among those with good drug adherence.

Conclusions

In a community based, integrated health plan setting, endometrial cancer incidence was lower in women on aromatase inhibitor compared to tamoxifen. Additionally, aromatase inhibitors may mitigate tamoxifen-associated endometrial cancer incidence. While there were somewhat fewer endometrial cancers in aromatase inhibitor versus no endocrine therapy users, further studies are needed for definitive assessment of this potential association.

Keywords: aromatase inhibitors, endometrial cancer, tamoxifen, breast cancer, Chemoprevention

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer and endometrial cancer are common diseases which share several risk factors. In 2014, over 232,000 breast cancers and over 40,000 deaths from breast cancer are anticipated in the United States. In the same period, over 52,000 endometrial cancers and over 8,500 deaths from endometrial cancer are anticipated as well.1

Obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30 kg/m2) substantially increases risk of developing and dying from both breast cancer2–5 and endometrial cancer.5–7 In addition, the risk of both endometrial cancer8 and breast cancer9 is increased in women with higher endogenous estrogen levels representing a target for therapeutic intervention.

Given similar risk factors for breast and endometrial cancers, an intervention with low toxicity which could reduce risk of both diseases could provide an attractive chemoprevention option. The potential for breast cancer risk reduction has been realized for breast cancer with the selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMS), tamoxifen and raloxifene,10–12 and more recently, with aromatase inhibitors, exemestane13 and anastrozole.14 Despite tamoxifen and raloxifene’s effectiveness in reducing breast cancer incidence, tamoxifen increases endometrial cancers10 while raloxifene at best has a neutral effect on risk11, and both increase venous thromboembolic events.11,12 As a result, for primary breast cancer prevention, as the risk to benefit ratio is not favorable, especially for older women and for tamoxifen,15 use of these selective estrogen receptor modulators for chemoprevention in clinical practice is extremely limited.16,17

Aromatase inhibitors, which substantially reduce both breast cancer incidence and endogenous estrogen levels, could potentially reduce endometrial cancer risk as well. In this regard, adjuvant endocrine therapy trials comparing tamoxifen to aromatase inhibitors use, in breast cancer survivors who used aromatase inhibitors had substantially lower endometrial cancer risk compared to tamoxifen.18 As those comparisons are against tamoxifen, more evidence is needed regarding the influence of aromatase inhibitors on endometrial cancer in women without tamoxifen exposure. Therefore, we examined the risk of endometrial cancer by tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitor use in a racially diverse cohort of nearly 17,064 postmenopausal breast cancer patient members of an integrated health plan. We hypothesized that endometrial cancer incidence would be lower in aromatase inhibitor only users compared to tamoxifen only users, endocrine therapy switchers, and non-users.

METHODS

A cohort of postmenopausal breast cancer patients was identified among members of Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC), a prepaid, non-profit, integrated group practice health plan with over 3.2 million members and 5,000 physicians providing care at 15 medical centers. Study data was extracted from electronic health records available from 1991–2010. The study protocol was approved by the KPSC institutional review board.

The methodology for data generation and analyses in this breast cancer cohort has been previously described.19 The KPSC-Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-affiliated cancer registry was used to assemble the cohort, determine eligibility, cancer therapy, and endometrial cancer diagnoses. Eligible were postmenopausal women with breast cancer (AJCC TNM Stages 0-IV, diagnosed from 1991 to 2010, and followed through December 2011), which was estrogen receptor and/or progestin receptor positive, with pharmacy benefits who remained a continuous health plan member until endometrial cancer diagnosis, health plan disenrollment, or death. Of 28,031 women with breast cancer in the registry, 3,194 who were not active Kaiser Permanente members one year prior to their breast cancer diagnosis and 7,773 who were not postmenopausal were excluded resulting in 17,064 postmenopausal women in the final cohort.

The KPSC computerized pharmacy data was used to identify tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors (letrozole, anastrozole, exemestane) dispensing dates and available prescriptions to calculate therapy durations. Four drug exposure categories were considered: tamoxifen use only, aromatase inhibitor use only, switchers and non-users. To be considered a switcher, at least 6 months of both tamoxifen and 6 months of aromatase inhibitor use was required. Women using either of these for < 6 months were considered non-users. Information on demographics was collected from the electronic health records.

Medication adherence was estimated from the medication possession ratio (MPR). The MPR was calculated as the number of days supplied (excluding last refill) divided by the number of days between first and last dispense date.20

The administrative and outpatient/inpatient utilization and diagnosis files were used to determine patient characteristics, health plan enrollment status, prevalent and incident comorbidities. Geocoded census data was used to determine education and covariant data and death files were used to determine cause and date of death.

The patient, breast cancer, and treatment characteristics are described by means, standard deviation, median and range for continuous variable and by percentage for categorized variables for the four adjuvant endocrine therapy groups. Comorbidity status in the year prior to breast cancer diagnosis was determined using the Deyo adoption of the Charleson Index.21 The overall incidence rates (per 1000 women/year) of endometrial cancers were compared across the endocrine therapy groups. Follow-up began on the date of breast cancer diagnosis, and ended on the date of the study outcome (endometrial cancer), death, termination of health plan membership, or study’s end (December 31, 2013), whichever occurred first. Cox proportional hazard models with time-dependent endocrine therapy use status presented as adjusted hazard ratios (HR) for endometrial cancer incidence rate and 95% confidence interval (CI). In this way, endocrine therapies were considered as binary time-dependent variables (i.e., 0 up to start date; 1 after start date).

We presented the most parsimonious model and the final Cox models were adjusted for age of diagnosis, year of diagnosis, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), geocoded median household income, hypertension, and chemotherapy. To address heterogeneity of endocrine therapy effects, the methods of Varadhan and Segal22 were used to examine the association by subgroups (Table 3). Similarly, to address confounding by indication, we also conducted sensitivity analyses based on patients exposed to endocrine therapy (tamoxifen only, aromatase inhibitors only and switchers). The Cox multivariable analyses were repeated including only those who had an >80% medication possession ratio (MPR) for their endocrine therapy, a standard measure for estimating medication compliance.20

TABLE 3.

Outcomes of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors diagnosed between 1991–2010

| Tamoxifen Only | AI Only | Both Tam and AI | No Hormones | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 5155 | 30.21 | 5303 | 31.08 | 3787 | 22.19 | 2819 | 16.52 | 17064 | 100.00 |

| Follow-up years | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.90 (5.28) | 4.13 (2.42) | 8.03 (3.77) | 5.08 (4.54) | 6.29 (4.46) | |||||

| Median | 6.87 | 3.75 | 8.06 | 3.6 | 5.23 | |||||

| Q1, Q3 | 3.30, 11.99 | 2.14, 5.79 | 5.03, 10.59 | 1.71, 7.08 | 2.70, 9.01 | |||||

| Follow-up months | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 94.55 (63.17) | 49.40 (28.98) | 96.15 (45.09) | 60.81 (54.34) | 75.30 (53.45) | |||||

| Median | 82.23 | 44.89 | 96.56 | 43.15 | 62.66 | |||||

| Q1, Q3 | 39.54, 143.57 | 25.57, 69.38 | 60.26, 126.79 | 20.46, 84.79 | 32.30, 107.85 | |||||

| Final follow-up event | ||||||||||

| Endometrial cancer | 89 | 1.73 | 17 | 0.32 | 24 | 0.63 | 18 | 0.64 | 148 | 0.87 |

| Death | 1509 | 29.27 | 581 | 10.96 | 995 | 26.27 | 611 | 21.67 | 3696 | 21.66 |

| Due to endometrial cancer | 3 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.03 | 2 | 0.07 | 8 | 0.05 |

| Due to other/unknown causes | 1506 | 29.21 | 579 | 10.92 | 994 | 26.25 | 609 | 21.60 | 3688 | 21.61 |

| Disenrollment | 1271 | 24.66 | 471 | 8.88 | 395 | 10.43 | 642 | 22.77 | 2779 | 16.29 |

| Completed follow-up by 12/31/2011 | 2286 | 44.35 | 4234 | 79.84 | 2373 | 62.66 | 1548 | 54.91 | 10441 | 61.19 |

| Overall rate of endometrial cancer per 1,000 person-years (95% CI)** | 1.83 (1.48,2.25) | 0.95 (0.57,1.48) | 1.50 (0.97,2.22) | 0.98 (0.60,1.51) | 1.45 (1.23,1.70) | |||||

RESULTS

The cohort of breast cancer patients was followed a maximum of 21 years (interquartile range, 2.7–9.0 years). Statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics of breast cancer patients among the four adjuvant endocrine therapy groups were commonly seen, largely related to the large sample size (Table 1). Women in the aromatase inhibitor only and no endocrine therapy groups were more commonly obese and had more comorbidity compared to the tamoxifen only group. Women in the aromatase inhibitor and switcher groups were also more recently diagnosed with breast cancer and had shorter follow-up given the later approval 6 date for adjuvant aromatase inhibitor use. Roughly 60% of the tamoxifen only users and 70% of the aromatase inhibitor users had an MPR≥80% (a measurement of good adherence) (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors diagnosed between 1991–2010

| Tamoxifen Only | AI Only | Both Tam and AI | No Hormones | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 5155 | 5303 | 3787 | 2819 | 17064 | 100.00 | ||||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| 55–59 | 925 | 17.94 | 1120 | 21.12 | 885 | 23.37 | 522 | 18.52 | 3452 | 20.23 |

| 60–69 | 2011 | 39.01 | 2335 | 44.03 | 1730 | 45.68 | 1091 | 38.70 | 7167 | 42.00 |

| 70–79 | 1603 | 31.10 | 1306 | 24.63 | 922 | 24.35 | 794 | 28.17 | 4625 | 27.10 |

| 80+ | 616 | 11.95 | 542 | 10.22 | 250 | 6.60 | 412 | 14.62 | 1820 | 10.67 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||||||

| 1991–1995 | 1432 | 27.78 | 16 | 0.30 | 303 | 8.00 | 383 | 13.59 | 2134 | 12.51 |

| 1996–2000 | 1928 | 37.40 | 45 | 0.85 | 1085 | 28.65 | 470 | 16.67 | 3528 | 20.68 |

| 2001–2005 | 975 | 18.91 | 1652 | 31.15 | 1762 | 46.53 | 724 | 25.68 | 5113 | 29.96 |

| 2005–2010 | 820 | 15.91 | 3590 | 67.70 | 637 | 16.82 | 1242 | 44.06 | 6289 | 36.86 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Race | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3859 | 74.86 | 3569 | 67.30 | 2779 | 73.38 | 2023 | 71.76 | 12230 | 71.67 |

| Hispanic | 402 | 7.80 | 518 | 9.77 | 346 | 9.14 | 218 | 7.73 | 1484 | 8.70 |

| Black | 489 | 9.49 | 657 | 12.39 | 347 | 9.16 | 333 | 11.81 | 1826 | 10.70 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 358 | 6.94 | 492 | 9.28 | 294 | 7.76 | 221 | 7.84 | 1365 | 8.00 |

| Other/Unknown* | 47 | 0.91 | 67 | 1.26 | 21 | 0.55 | 24 | 0.85 | 159 | 0.93 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Geocoded Median Household Income | ||||||||||

| Lower 25% (<=$49,227) | 1361 | 26.40 | 1261 | 23.78 | 873 | 23.05 | 699 | 24.80 | 4194 | 24.58 |

| > 25–50% ($49,228–$66,803) | 1290 | 25.02 | 1261 | 23.78 | 929 | 24.53 | 713 | 25.29 | 4193 | 24.57 |

| > 50–75% ($66,804–$88,548) | 1242 | 24.09 | 1338 | 25.23 | 944 | 24.93 | 674 | 23.91 | 4198 | 24.60 |

| Top 25% (>=$88,549) | 1112 | 21.57 | 1402 | 26.44 | 1004 | 26.51 | 670 | 23.77 | 4188 | 24.54 |

| Unknown/Missing | 150 | 2.91 | 41 | 0.77 | 37 | 0.98 | 63 | 2.23 | 291 | 1.71 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Comorbities (1 year before BC dx) | ||||||||||

| 0 | 4010 | 77.79 | 3166 | 59.70 | 2752 | 72.67 | 1823 | 64.67 | 11751 | 68.86 |

| 1 to 2 | 895 | 17.36 | 1524 | 28.74 | 865 | 22.84 | 671 | 23.80 | 3955 | 23.18 |

| 3+ | 250 | 4.85 | 613 | 11.56 | 170 | 4.49 | 325 | 11.53 | 1358 | 7.96 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Hypertension (anytime up to follow-up) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 3982 | 77.25 | 4081 | 76.96 | 3038 | 80.22 | 2065 | 73.25 | 13166 | 77.16 |

| No | 1173 | 22.75 | 1222 | 23.04 | 749 | 19.78 | 754 | 26.75 | 3898 | 22.84 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Diabetes (anytime up to follow-up) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1330 | 25.80 | 1521 | 28.68 | 978 | 25.83 | 703 | 24.94 | 4532 | 26.56 |

| No | 3825 | 74.20 | 3782 | 71.32 | 2809 | 74.17 | 2116 | 75.06 | 12532 | 73.44 |

| P | 0.0003 | |||||||||

| BMI (closest to BC dx) | ||||||||||

| Underweight | 8 | 0.16 | 24 | 0.45 | 5 | 0.13 | 11 | 0.39 | 48 | 0.28 |

| Normal | 198 | 3.84 | 675 | 12.73 | 112 | 2.96 | 275 | 9.76 | 1260 | 7.38 |

| Overweight | 203 | 3.94 | 896 | 16.90 | 163 | 4.30 | 294 | 10.43 | 1556 | 9.12 |

| Obese | 219 | 4.25 | 1136 | 21.42 | 148 | 3.91 | 382 | 13.55 | 1885 | 11.05 |

| Missing | 4527 | 87.82 | 2572 | 48.50 | 3359 | 88.70 | 1857 | 65.87 | 12315 | 72.17 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

In general, the tumor characteristics were quite similar in the four adjuvant endocrine therapy groups (Table 2). Breast cancers in women in the aromatase inhibitor group were somewhat more commonly at higher stage (stage III). Women in the no adjuvant endocrine therapy group more likely had ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (stage 0) disease (note, a few women initially diagnosed with DCIS (n=76) might have later used aromatase inhibitors for a recurrence). With those exceptions, there were no other major differences between groups in breast cancer stage at diagnosis or primary surgical therapy. Women given adjuvant chemotherapy were somewhat more likely to have received no endocrine therapy compared to those given tamoxifen only and substantially more likely compared to those given aromatase inhibitors. Women given both tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors (sequentially) more closely followed the demographics and breast cancer presentation characteristics of tamoxifen only users.

TABLE 2.

Tumor characteristics of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors diagnosed between 1991–2010

| Tamoxifen Only | AI Only | Both Tam and AI | No Hormones | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 5155 | 5303 | 3787 | 2819 | 17064 | 100.00 | ||||

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Stage 0 | 533 | 10.34 | 76 | 1.43 | 48 | 1.27 | 815 | 28.91 | 1472 | 8.63 |

| Stage I | 2782 | 53.97 | 2802 | 52.84 | 1611 | 42.54 | 1408 | 49.95 | 8603 | 50.42 |

| Stage II | 1584 | 30.73 | 1766 | 33.30 | 1682 | 44.42 | 442 | 15.68 | 5474 | 32.08 |

| Stage III | 182 | 3.53 | 505 | 9.52 | 304 | 8.03 | 81 | 2.87 | 1072 | 6.28 |

| Stage IV | 74 | 1.44 | 154 | 2.90 | 142 | 3.75 | 73 | 2.59 | 443 | 2.60 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Laterality | ||||||||||

| Right | 2541 | 49.29 | 2626 | 49.52 | 1889 | 49.88 | 1369 | 48.56 | 8425 | 49.37 |

| Left | 2609 | 50.61 | 2662 | 50.20 | 1888 | 49.85 | 1445 | 51.26 | 8604 | 50.42 |

| Single sode NOS | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.01 |

| Both sides NOS | 2 | 0.04 | 3 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 5 | 0.03 |

| Paired side NOS | 3 | 0.06 | 10 | 0.19 | 10 | 0.26 | 5 | 0.18 | 28 | 0.16 |

| P | 0.2278 | |||||||||

| Estrogen Status | ||||||||||

| Positive | 5148 | 99.86 | 5285 | 99.66 | 3781 | 99.84 | 2802 | 99.40 | 17016 | 99.72 |

| Negative | 7 | 0.14 | 17 | 0.32 | 5 | 0.13 | 16 | 0.57 | 45 | 0.26 |

| Test not done | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.01 |

| Unknown/Missing | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.01 |

| P | 0.0058 | |||||||||

| Progesterone Status | ||||||||||

| Positive | 3212 | 62.31 | 3585 | 67.60 | 2186 | 57.72 | 1837 | 65.16 | 10820 | 63.41 |

| Negative | 521 | 10.11 | 582 | 10.97 | 372 | 9.82 | 312 | 11.07 | 1787 | 10.47 |

| Test not done | 928 | 18.00 | 150 | 2.83 | 740 | 19.54 | 244 | 8.66 | 2062 | 12.08 |

| Unknown/Missing | 494 | 9.58 | 986 | 18.59 | 489 | 12.91 | 426 | 15.11 | 2395 | 14.04 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| HER2 Status | ||||||||||

| Positive | 56 | 1.09 | 365 | 6.88 | 125 | 3.30 | 66 | 2.34 | 612 | 3.59 |

| Negative | 749 | 14.53 | 2869 | 54.10 | 1344 | 35.49 | 610 | 21.64 | 5572 | 32.65 |

| Test not done | 1090 | 21.14 | 771 | 14.54 | 876 | 23.13 | 865 | 30.68 | 3602 | 21.11 |

| Unknown/Missing | 3260 | 63.24 | 1298 | 24.48 | 1442 | 38.08 | 1278 | 45.34 | 7278 | 42.65 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Primary Therapy | ||||||||||

| Breast conserving surgery + radition | 1827 | 35.44 | 2071 | 39.05 | 1366 | 36.07 | 825 | 29.27 | 6089 | 35.68 |

| BCS (no radiation) | 953 | 18.49 | 951 | 17.93 | 608 | 16.05 | 775 | 27.49 | 3287 | 19.26 |

| Mastectomy (with or w/o radiation) | 2205 | 42.77 | 2040 | 38.47 | 1616 | 42.67 | 1019 | 36.15 | 6880 | 40.32 |

| No Primary Therapy | 86 | 1.67 | 205 | 3.87 | 84 | 2.22 | 175 | 6.21 | 550 | 3.22 |

| Other/Unknown/Missing | 84 | 1.63 | 36 | 0.68 | 113 | 2.98 | 25 | 0.89 | 258 | 1.51 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Adjuvant RT | ||||||||||

| Yes | 3921 | 76.06 | 3531 | 66.58 | 2515 | 66.41 | 251 | 8.90 | 10218 | 59.88 |

| No | 1158 | 22.46 | 1684 | 31.76 | 1141 | 30.13 | 2526 | 89.61 | 6509 | 38.14 |

| Unknown/Missing | 76 | 1.47 | 88 | 1.66 | 131 | 3.46 | 42 | 1.49 | 337 | 1.97 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Adjuvant Chemo | ||||||||||

| Yes | 722 | 14.01 | 1773 | 33.43 | 1439 | 38.00 | 281 | 9.97 | 4215 | 24.70 |

| No | 4346 | 84.31 | 3504 | 66.08 | 2229 | 58.86 | 2510 | 89.04 | 12589 | 73.78 |

| Unknown/Missing | 87 | 1.69 | 26 | 0.49 | 119 | 3.14 | 28 | 0.99 | 260 | 1.52 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Histology | ||||||||||

| DCIS | 222 | 4.31 | 33 | 0.62 | 25 | 0.66 | 317 | 11.25 | 597 | 3.50 |

| LCIS (lobular ca in situ) | 3 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.04 | 2 | 0.05 | 16 | 0.57 | 23 | 0.13 |

| IDC (invasive ductal ca) | 2929 | 56.82 | 3220 | 60.72 | 2138 | 56.46 | 1223 | 43.38 | 9510 | 55.73 |

| ILC (invasive lobular ca) | 512 | 9.93 | 512 | 9.65 | 437 | 11.54 | 175 | 6.21 | 1636 | 9.59 |

| Other/Mixed category | 1489 | 28.88 | 1536 | 28.96 | 1185 | 31.29 | 1088 | 38.60 | 5298 | 31.05 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Grade | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1362 | 26.42 | 1498 | 28.25 | 987 | 26.06 | 739 | 26.21 | 4586 | 26.88 |

| 2 | 2336 | 45.32 | 2590 | 48.84 | 1756 | 46.37 | 1180 | 41.86 | 7862 | 46.07 |

| 3 | 868 | 16.84 | 1053 | 19.86 | 753 | 19.88 | 601 | 21.32 | 3275 | 19.19 |

| Unknown/Missing | 589 | 11.43 | 162 | 3.05 | 291 | 7.68 | 299 | 10.61 | 1341 | 7.86 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Size of tumor (cm) | ||||||||||

| No mass | 9 | 0.17 | 12 | 0.23 | 14 | 0.37 | 3 | 0.11 | 38 | 0.22 |

| <1 | 1057 | 20.50 | 1103 | 20.80 | 519 | 13.70 | 1015 | 36.01 | 3694 | 21.65 |

| 1 – 1.9 | 2174 | 42.17 | 2154 | 40.62 | 1453 | 38.37 | 883 | 31.32 | 6664 | 39.05 |

| 2 – 2.9 | 1002 | 19.44 | 1100 | 20.74 | 878 | 23.18 | 395 | 14.01 | 3375 | 19.78 |

| 3 – 3.9 | 332 | 6.44 | 379 | 7.15 | 365 | 9.64 | 135 | 4.79 | 1211 | 7.10 |

| 4 – 4,9 | 128 | 2.48 | 176 | 3.32 | 153 | 4.04 | 67 | 2.38 | 524 | 3.07 |

| >=5 | 168 | 3.26 | 294 | 5.54 | 234 | 6.18 | 114 | 4.04 | 810 | 4.75 |

| Unknown/missing | 285 | 5.53 | 85 | 1.60 | 171 | 4.52 | 207 | 7.34 | 748 | 4.38 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Lymph nodes | ||||||||||

| Positive | 1021 | 19.81 | 1499 | 28.27 | 1416 | 37.39 | 263 | 9.33 | 4199 | 24.61 |

| Negative | 3040 | 58.97 | 3314 | 62.49 | 2032 | 53.66 | 1617 | 57.36 | 10003 | 58.62 |

| Unknown/missing | 1094 | 21.22 | 490 | 9.24 | 339 | 8.95 | 939 | 33.31 | 2862 | 16.77 |

| P | <.0001 | |||||||||

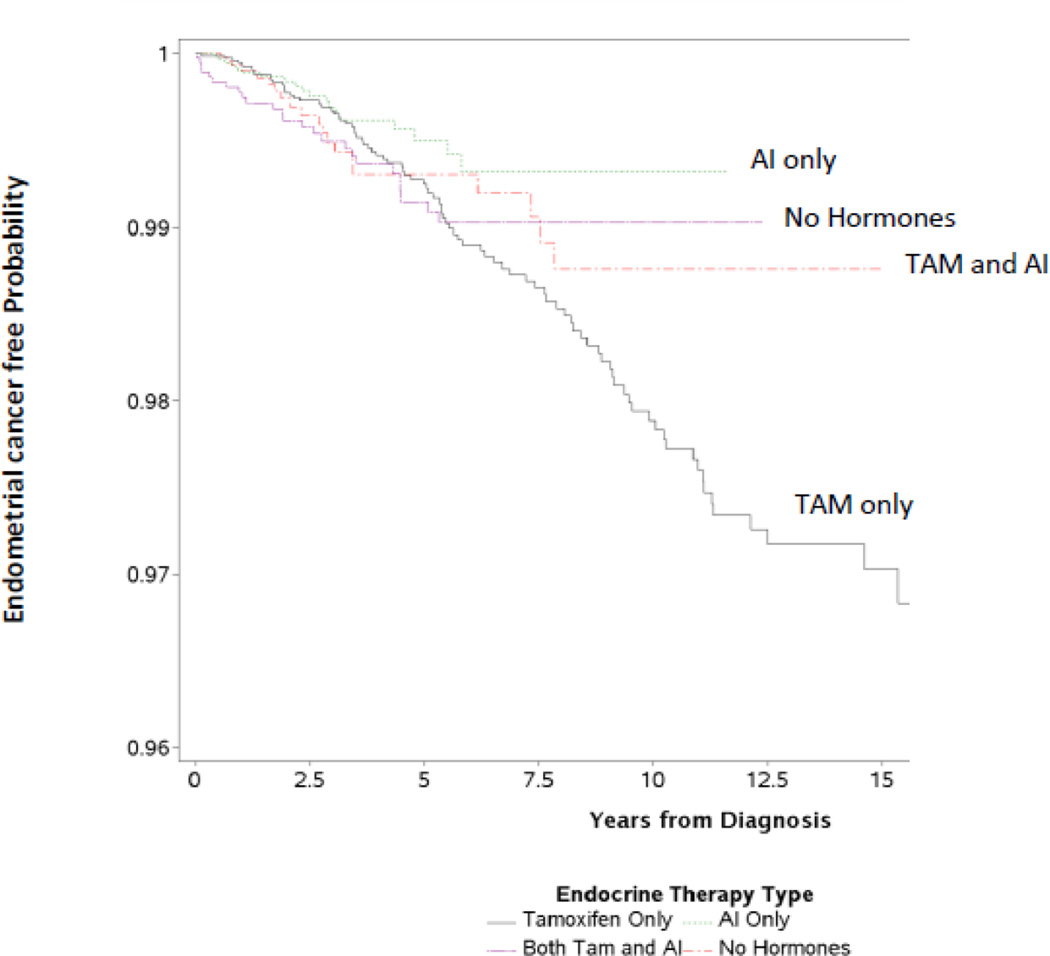

In the cohort of 17,064 women with breast cancer patients, 148 developed endometrial cancer during the 21-year study period. A small percentage disenrolled (n=2,779, 16.3%) from the health plan; however, we were able to identify the patients who eventually died of endometrial cancer by linking with the State of California’s death certificate files (n=8; these women were included as cases in the analysis) (Table 3). The endometrial cancer incidence rates by endocrine therapy group are outlined in Table 3. The rate of endometrial cancer was the lowest in the aromatase inhibitor only group (0.95/1,000 person-years), followed by the no endocrine therapy group (0.98/1,000 person-years). The greatest endometrial cancer rate was among the tamoxifen only group (1.83/1,000 person-years). The Kaplan Meier curves (Figure 1) are consistent with the crude person-year rates and also show the greatest risk of endometrial cancer in the tamoxifen only group.

Figure 1.

In the multi-variable-adjusted Cox analyses (Table 4), while the endometrial cancer incidence was 36% higher in the tamoxifen only group compared to no endocrine therapy group (HR 1.36, 95% CI 0.84–2.22, P=0.22) and the endometrial cancer incidence rate was 29% lower in the aromatase inhibitor only group compared to no endocrine therapy group (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.37–1.35, P=0.30), neither difference was statistically significant. To address confounding by indication, the same analyses were repeated on the subset exposed to the endocrine 7 treatments (n=14,245; tamoxifen only was used as the reference group). The endometrial cancer incidence was 48% lower in the aromatase inhibitor only group compared to the tamoxifen group, a difference which was statistically significant (HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31–0.87, P=0.01). The findings in the switching group (tamoxifen to aromatase inhibitor) were intermediate with a borderline lower endometrial cancer incidence rate seen compared to that in the tamoxifen only group (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.42–1.06, P=0.08).

TABLE 4.

Endometrial Cancer Risk by Endocrine Adjuvant Therapy in Postmenopausal Women with Breast Cancer

| Contrast | Adjusted HR* | 95% CI | Pr > ChiSq | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Women | ||||

| Tam only vs. No hormones | 1.36 | 0.84 | 2.22 | 0.22 |

| AI only vs. No hormones | 0.71 | 0.38 | 1.35 | 0.30 |

| AI only vs. Tam only | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.87 | 0.01 |

| Tam → AI vs Tam only | 0.67 | 0.42 | 1.06 | 0.08 |

| MPR≥80% | ||||

| AI only vs. Tam only | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.8 | 0.008 |

| Tam → AI vs Tam only | 0.59 | 0.34 | 1.01 | 0.055 |

Adjusted for: race/ethnicity, age at dx, income, diabetes, hypertension, chemotherapy

Analysis based on women who had good adherence to endocrine therapy (MPR>80%) demonstrated stronger associations. In these sensitivity analyses, women who took aromatase inhibitors only had an adjusted HR=0.40 (95% CI: 0.20–0.79) versus tamoxifen only. The adjusted HR for switchers was HR=0.59 (95% CI: 0.34–1.01) versus tamoxifen only (Table 4). The most parsimonious models are presented in Table 4; those variables that changed the HR by 10% or more were retained in the model (race/ethnicity; age at breast cancer diagnosis, geocoded income, diabetes, hypertension, and chemotherapy).

DISCUSSION

In a community based integrated health plan setting, use of aromatase inhibitors compared to tamoxifen for adjuvant endocrine therapy in women with early stage breast cancer results in substantially fewer endometrial cancers. In addition, aromatase inhibitor use after tamoxifen in a switching strategy may abrogate tamoxifen-associated endometrial cancer risk. While there were fewer endometrial cancers in breast cancer patients receiving aromatase inhibitor compared to those managed without endocrine therapy, further studies are needed for definitive assessment of aromatase inhibitor influence on endometrial cancer risk. The current findings regarding relative aromatase inhibitor compared to tamoxifen influence on endometrial cancer provide further support for current recommendations23 that an aromatase inhibitor be included as a component of adjuvant management of postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer.

The current clinical practice findings reflect and expand results from randomized clinical trials. In the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) P-1 prevention trial, tamoxifen significantly increased endometrial cancers compared to placebo (HR 3.28, 95% CI 1.87–6.03).10 During the 5 years of therapy in the International Breast Cancer Intervention Study 1 (IBIS-1), a comparable increase in endometrial cancers with tamoxifen was seen (Odds ratio [OR] 3.76, 95% CI 1.20–15.56, p=0.011), with no further increase through 16.0 years median 8 follow-up but with excess endometrial cancer deaths compared to placebo (5 vs. 0, p = 0.06).24 In the NSABP P-2 trial, the SERM raloxifene resulted in fewer endometrial cancers compared to tamoxifen (Relative Risk [RR] 0.55, 95% CI 0.36–0.83) (Vogel 2010).

In addition, the current results suggestive of an aromatase inhibitor effect in abrogating tamoxifen adverse influence on endometrial histology is supported by findings from randomized adjuvant therapy trials.24 In a meta-analysis of five trials of sequenced therapy, endometrial cancer risk was substantially lower in women sequenced to aromatase inhibitors compared to those continued on tamoxifen (OR 0.31, p=0.007).18 In terms of potential mediating mechanisms, a prospective clinical study found long-term aromatase inhibitor use reversed endometrial thickening associated with tamoxifen.25

A limited number of randomized, placebo- controlled clinical trials have reported on aromatase inhibitor influence on endometrial cancer in adjuvant breast cancer26 or chemoprevention,13,14 settings. Results from these trials are shown in Table 5. While the number of cases is limited, they are suggestive of a lower endometrial cancer incidence with aromatase inhibitor than with placebo. Updates of these findings are anticipated (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Aromatase Inhibitors vs. Placebo/No Hormone Therapy in Early Breast Cancer and Endometrial Cancer Risk

| Trial | Author (reference) |

Endocrine treatment | Subjects (n) | Endometrial Cancer (n) |

AI vs. Placebo | Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA.17 | Goss | Letrozole vs placebo | 5187 | 15 | 4 vs 11 | Randomized Adjuvant Trial after Tamoxifen |

| IBIS-II | Cuzick | Anastrozole vs placebo | 1920 | 8 | 3 vs 5 | Randomized Prevention Trial |

| MAP.3 | Goss | Exemestane vs placebo | 4560 | 5 | 3 vs 2 | Randomized Prevention Trial |

An intervention which could reduce the risk of both breast cancer and endometrial cancer would have substantial chemoprevention impact, especially for postmenopausal women who are obese. Currently, more than 33% of US adults are obese.27 In the increasing population of US women with BMI > 35 kg/m2, endometrial cancer risk is about 7 times greater than in a normal weight woman.7 As a result, since endometrial cancer incidence is usually about 20% of breast cancer incidence,1 such women are at similar risk for endometrial cancer comparable to their already high breast cancer risk. While endometrial cancer commonly is considered to have a favorable prognosis, it is not a screen detected cancer and carries substantial 15–20% 3-year mortality.28 Thus, obese women, especially those with BMI > 35 kg/m2, are at extremely high risk of being diagnosed with and dying of breast and/or endometrial cancer. As the number needed-to- treat to prevent one breast cancer with the aromatase inhibitor exemestane in the MAP.3 primary prevention trial was only 26,13 an intervention which could reduce both breast cancer and endometrial cancer risk in such a high risk obese population could result in a substantial number of those treated having benefit.

While our findings on aromatase inhibitor influence on endometrial cancer risk in women without tamoxifen exposure are inconclusive, emerging results suggest a potential inhibitory effect. Anti-proliferative activity has been seen with aromatase inhibitor use against early stage endometrial cancer and atypical hyperplasia of the endometrium.29 The aromatase inhibitor letrozole reduced endometrial hyperplasia in a small clinical study30 and in a pilot neoadjuvant trial, the aromatase inhibitor anastrozole significantly decreased endometrial cancer proliferation as measured by KI-67 expression.31 In addition, aromatase inhibitor use has shown some activity against endometrial cancer in the advanced disease setting as well.31–33 In a phase II study in 51 patients with advanced or relapsed endometrial cancer, in estrogen receptor positive cases, with exemestane use (25 mg/d), a response rate of 10% and lack of progression after 6 months in 35% of patients was seen.33 Taken together, such findings support further evaluation of a potential role for aromatase inhibitor targeting subclinical endometrial cancer in primary prevention settings.

With respect to cost considerations of using aromatase inhibitors for cancer prevention, as a component of the Affordable Care Act, any preventive intervention endorsed by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has to be provided by all US health insurance plans without cost or co-pay. The USPSTF has endorsed tamoxifen and raloxifene for breast cancer risk reduction.34 However, now with two full scale, randomized, placebo-controlled trials showing substantial (between 50–65%) reduction in breast cancer risk with aromatase inhibitor use13, 14 it is likely that aromatase inhibitor will be added to their recommendations in the near future, at which time, cost for individual women will no longer be a factor.

This study has strengths. Analytic information comes from a large population of well characterized women with breast cancer treated in a closed healthcare system with electronic health records thus making information available on patient demographics, medical history including endometrial cancer risk factors, and comprehensive information on breast cancer therapy including adjuvant endocrine therapy use. Information on endometrial cancer comes from a Kaiser Permanente-SEER affiliated tumor registry. Previous analyses in this cohort found greatest reduction in breast cancer recurrence risk in high adherers to aromatase inhibitor use,19 consistent with recent randomized trial findings,23 and provide support for the reliability of the approach to address additional questions. Importantly, we were able to remove the effect of variable medical coverage as a source of bias because all study subjects were part of the KPSC health system and received full pharmacy coverage.

Study limitations include the change in endocrine therapy use over time resulting in a shorter time period for those given aromatase inhibitors alone and lack of information on the rationale underlying the individual therapy choices. However, because aromatase inhibitors became available in the market since mid-2000’s, we were able to follow women through 2011.

In conclusion, women with breast cancer experience fewer endometrial cancers with aromatase inhibitor compared to tamoxifen use. In addition, aromatase inhibitors may mitigate the tamoxifen-associated increase in endometrial cancer use. While a single intervention which could decrease the high risk of breast cancer and endometrial cancer in obese postmenopausal women would address an unmet need, further study is needed to determine the influence of aromatase inhibitors on endometrial cancer in women without tamoxifen exposure.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: California Breast Cancer Research Program 190OB-0201 (“Cardiovascular Toxicity Following Aromatase Inhibitor Use”) & R01CA093772 (RH)

RTC has received speaker’s fees and honorarium from Novartis; honorarium for advisory boards and consulting for Novartis, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk and Amgen.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: No other author has conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chlebowski RT, Aiello E, McTiernan A. Weight loss in breast cancer patient management. J. Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1128–1143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Protani M, Coory M, Martin JH. Effect of obesity on survival of women with breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0990-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Pergola G, Silvestris F. Obesity as a major risk factor for cancer. J Obes. 2013;2013:291546. doi: 10.1155/2013/291546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagle CM, Marquart L, Bain CJ, et al. Impact of weight change and weight cycling on risk of different subtypes of endometrial cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2717–2726. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chlebowski R, Anderson GL, Sarto G, et al. Continued combined estrogen plus progestin and endometrial cancer in postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative randomized clinical trial. European Multidisciplinary Cancer Congress. 2013 Presidential Session: Best and Late Breaking Abstracts, 13LBA. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao H, Jiang Y, Liu Y, Yun C, Li L. Endogenous Estrogen Metabolites as Biomarkers for Endometrial Cancer via a Novel Method of Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry with Hollow Fiber Liquid-Phase. Microextraction. Horm Metab Res. 2014 Apr 10; doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1371865. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farhat GN, Parimi N, Chlebowski RT, et al. Sex hormone levels and risk of breast cancer with estrogen plus progestin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1496–1503. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: Current status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1652–1662. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Update of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Study of tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 Trial: preventing breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;3:696–706. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visvanathan K, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Use of pharmacologic interventions for breast cancer risk reduction: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J. Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2942–2962. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Alex-Martin LJ, et al. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2381–2391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, et al. Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): an international, double-blind, randomized placebo controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;383:1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older. J Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:2327–2333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chlebowski RT. Current concepts: Breast cancer chemoprevention. Pol Arch Med. 2014;124:191–199. doi: 10.20452/pamw.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waters EA, McNeel TS, Stevens WM, Freedman AN. Use of tamoxifen and raloxifene for breast cancer chemoprevention in 2010. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:875–880. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2089-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aydiner A. Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcome and toxicity in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors in postmenopausal women. Breast. 2013;22:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haque R, Ahmed SA, Fisher A, et al. Effectiveness of aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen in reducing subsequent breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2012;1:318–237. doi: 10.1002/cam4.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sikka R, Xia F, Aubert RE. Estimating medication persistency using administrative claims data. Am J Mang Care. 2005;11:449–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cleves MA, Sanchez N, Draheim M. Evaluation of two competing methods for calculating Charlson’s comorbidity index when analyzing short-term mortality using administrative data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:903–908. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varadhan R, Segal JB, Boyd CM, Wu AW, Weiss CO. A framework for the analysis of heterogeneity of treatment effect in patient-centered outcomes research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:818–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Cawthorn S, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: extended long-term follow-up of the IBIS-I breast cancer prevention trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:67–75. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71171-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burstein HJ, Prestrud AA, Seidenfeld J, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline: update on adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptorpositive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;2:3784–3796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markovitch O, Tepper R, Fishman A, Aviram R, Cohen I. Long term protective effect of aromatase inhibitors on the endometrium of postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Breast. Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:321–326. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9941-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1793–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uharcek P. Prognostic factors in endometrial carcinoma. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34:776–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao C, Wang Y, Tian W, Zhu Y, Xue F. The therapeutic significance of aromatase inhibitors in endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li HZ, Chen XN, Qiao J. Letrozole as primary therapy for endometrial hyperplasia in young women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thangavelu A, Hewitt MJ, Quinton ND, Duffy SR. Neoadjuvant treatment of endometrial cancer using anastrozole: a randomized pilot study. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;131:613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altman AD, Thompson J, Nelson GS, Chu P, Nation J, Ghatage P. Use of aromatase inhibitors as first- and second-line medical therapy in patients with endometrial adenocarcinoma: a retrospective study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34:664–672. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)35320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindemann K, Malander S, Christensen RD, et al. Examestane in advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma: a prospective phase II study by the Nordic Society of Gynecologic Oncology (NSGO) BMC Cancer. 2014;14:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinsinger L, Harris R, Lewis C, Wooddell M. Chemoprevention of breast cancer [internet] U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses. 2002 Jul [Google Scholar]