Abstract

Adiaspiromycosis is a pulmonary infection caused by the soil fungi, Emmonsia crescens and E. parva. It primarily affects small mammals and can range from an asymptomatic condition to fatal disseminated disease. We detected a granuloma containing fungal spherules, which were morphologically consistent with the adiaspores of E. crescens in the lungs of a female Hokkaido sika deer. This is the first reported case of adiaspiromycosis involving a cervid in the world.

Keywords: adiaspiromycosis, Emmonsia crescens, Hokkaido sika deer

Adiaspiromycosis is a mycotic pulmonary disease caused by dimorphic fungi from the genus Emmonsia; i.e., E. crescens and E. parva. It primarily affects small mammals, although it rarely occurs in humans [14]. Adiaspiromycosis is unique among fungal infections in that the associated conidia do not replicate in the host’s tissues [3]. In adiaspiromycosis, the inhaled dust-borne conidia fail to germinate at the elevated temperatures found in host tissue and instead increase in volume to form large spherical, non-proliferating structures called adiaspores [14]. The adiaspores elicit granulomatous reactions, and the severity and extent of any pulmonary involvement depend on the host’s immune status and the quantity of inhaled conidia [5, 14]. Adiaspiromycosis has been reported to occur in more than 100 species of small mammals including rodents, insectivores, carnivores, lagomorphs and marsupials [2, 4, 14], but it is rare in large herbivores (one case involving a goat and another involving a horse have been reported) [9, 13]. This paper describes the first case of adiaspiromycosis involving a deer.

The female fawn described in the present case was one of a number of Hokkaido sika deer (Cervus nippon yesoensis) captured in a corral trap around Lake Akan in the eastern district of Hokkaido, Japan, in March 2014. The deer was used for a feed study and then slaughtered in October 2014 as planned. The animal was estimated to be 2-year-old according to an assessment of the number of layers of tooth cement [8]. A few liver flukes were found in the intrahepatic bile duct during a gross examination performed at slaughter. There were no significant lesions in the animal’s other organs. The liver, spleen, kidneys, heart, lungs, pancreas, adrenal glands, alimentary tract, diaphragm and brain were collected; fixed in 10% formalin; embedded in paraffin and cut into 4 µm-thick sections, before being stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Selected sections were subjected to periodic acid-Schiff reaction and Grocott’s methenamine silver staining.

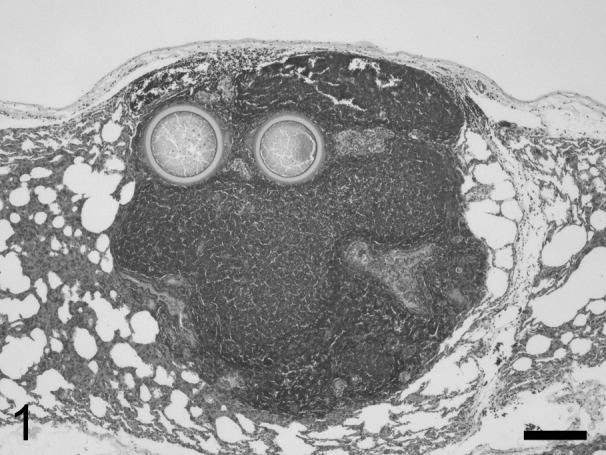

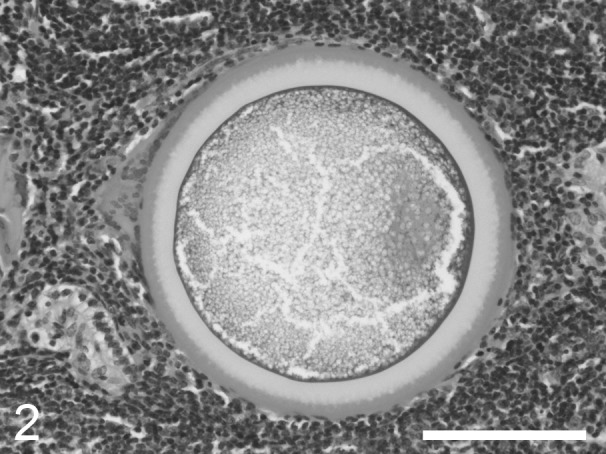

Histologically, the biliary mucosa was hyperplastic and exhibited submucosal lymphoid follicle hyperplasia. Perifollicular neutrophil infiltration was seen in the spleen together, and multifocal mild non-suppurative interstitial nephritis was detected in the kidneys. Sarcocysts were scattered throughout the striated muscle fibers in the heart, tongue and diaphragm. In the lungs, a localized lesion containing central fungal spherules was observed (Fig. 1). The spherules measured 227‒260 µm in diameter and had 22‒25 µm thick-walls, which appeared to be bilaminar according to hematoxylin and eosin staining (Fig. 2). In each spherule, the outer third of the wall was stained with eosin, while the inner two-thirds were not stained. The entire wall was stained purple by periodic acid-Schiff reaction and black by Grocott’s methenamine silver stain (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). The spherules contained fine granular material, but did not exhibit endospores. The spherules were surrounded by a few macrophages, multinucleated giant cells and fused lymphoid follicles. The histological appearance, size and staining characteristics of the spherules were consistent with those found in previous cases of adiaspiromycosis caused by E. crescens [7, 14].

Fig. 1.

Two adiaspores are surrounded by fused lymphoid follicles, forming a nodular lesion in the lung. Hematoxylin and eosin. Bar=200 µm.

Fig. 2.

An adiaspore with fine granular contents and a thick bilaminar wall. The outer third of the adiaspore’s wall is eosinophilic, and the inner two-thirds are unstained. Hematoxylin and eosin. Bar=100 µm.

Adiaspiromycosis is a pulmonary disease caused by the saprophytic soil fungi, E. crescens and E. parva. It mainly affects small animals, but rarely affects humans. E. crescens has been identified in many species of rodents, insectivores, carnivores, lagomorphs and marsupials around the world [2, 4, 14]. E. parva is more geographically restricted and is associated with various rodents, lagomorphs, carnivores and marsupials found in Central Asia, Africa, Australia and parts of America [14]. Although E. parva was discovered first, E. crescens appears to be the primary causative agent of adiaspiromycosis in both animals and humans. E. parva and E. crescens differ in their maximum in vitro growth temperatures and the sizes of their adiaspores [14]. In vitro, the conidia of E. crescens enlarge to become adiaspores measuring 20–140 µm in diameter at 37°C, whereas E. parva requires a temperature of 40°C to produce adiaspores. The adiaspores of E. parva measure 8–20 µm in diameter. In vivo, E. crescens forms adiaspores of 50–500 µm in diameter with 10–70 µm-thick walls, and E. parva produces adiaspores of 10–40 µm in diameter with thin walls. Adiaspiromycosis is generally diagnosed by examining the characteristics of adiaspores found in lung tissue specimens with light microscopy, as there are no reliable serological tests for the condition and culture tests are often fruitless [14]. Amplifying and sequencing conserved regions of the nuclear 28S rRNA gene in affected lung tissue allows E. crescens to be detected [12]; however, there were no specimens available in the present case after the histological examinations.

In Japan, adiaspiromycosis has been reported in three rodent species, Eothenomys smithii, Apodemus speciosus and Apodemus argenteus, and a pika, Ochotona hyperborea yesoensis [6, 11, 15]. Interestingly, the animal in the present case and those described in the latter reports were from northern, cool parts of Japan. Regarding large herbivores, adiaspiromycosis has only been reported in a goat and a horse. In the former case, a considerable number of spherules that were compatible with Emmonsia sp. were observed in the lungs of a 2 1/2-year-old female goat; however, this was considered to be an incidental finding. The equine case, which involved a 12-year-old male Quarter Horse, exhibited more extensive disseminated pulmonary disease caused by E. crescens. In veterinary medicine, in addition to these animals, incidental findings that were indicative of adiaspiromycosis have been reported in two dogs [1, 10]. We have detected no similar lesions so far on histological sections from 108 Hokkaido sika deer which were captured and farmed for several months in the eastern district of Hokkaido, Japan (unpublished data). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of adiaspiromycosis involving an animal belonging to the family Cervidae in the world. As in the previous caprine and canine cases, the adiaspores and associated lesions seen in the present case were considered to be incidental findings.

Emmonsia spp. also occasionally cause human infections, which range from localized, asymptomatic pulmonary disease in immunocompetent patients to necrogranulomatous pneumonia and death in immunocompromised hosts, such as patients with AIDS [5, 14]. There have been several case reports about E. crescens infection in Japan [6, 11, 15, this report]; therefore, it will be necessary to determine the prevalence of this potential human pathogen among Japan fauna in future.

Supplementary

REFERENCES

- 1.al-Doory Y., Vice T. E., Mainster M. E.1971. Adiaspiromycosis in a dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 159: 87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borman A. M., Simpson V. R., Palmer M. D., Linton C. J., Johnson E. M.2009. Adiaspiromycosis due to Emmonsia crescens is widespread in native British mammals. Mycopathologia 168: 153–163. doi: 10.1007/s11046-009-9216-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandler F. W., Kaplan W., Ajello L.1980. Color Atlas and Text of Histopathology of Mycotic Disaease. Wolfe Medical Publishers, London. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dvorák J.1969. Survey of animals examined on the presence of adiaspores of Emmonsia crescens Emmons et Jellison, 1960. Folia Parasit. 16: 349–355. [Google Scholar]

- 5.England D. M., Hochholzer L.1993. Adiaspiromycosis: an unusual fungal infection of the lung. Report of 11 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 17: 876–886. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199309000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jellison W. L.1958. Haplomycosis in Japan and Africa. Mycologia 50: 580–583. doi: 10.2307/3756120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones T. C., Hunt R. D., King N. W.1997. Diseases caused by fungi. pp. 505–547. In: Veterinary Pathology. 6th ed. (Jones, T. C., Hunt, R. D. and King, N. W. eds.), Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koike H., Ohtaishi N.1985. Prehistoric hunting pressure estimated by the age composition of excavated sika deer (Cervus nippon) using the annual layer of tooth cement. J. Archaeol. Sci. 12: 443–456. doi: 10.1016/0305-4403(85)90004-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koller L. D., Helfer D. H.1978. Adiaspiromycosis in the lungs of a goat. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 173: 80–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koller L. D., Patton N. M., Whitsett D. K.1976. Adiaspiromycosis in the lungs of a dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 169: 1316–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohbayashi M., Ishimoto Y.1971. Two cases of adiaspiromycosis in small mammals. Jpn. J. Vet. Res. 19: 103–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson S. W., Sigler L.1998. Molecular genetic variation in Emmonsia crescens and Emmonsia parva, etiologic agents of adiaspiromycosis, and their phylogenetic relationship to Blastomyces dermatitidis (Ajellomyces dermatitidis) and other systemic fungal pathogens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36: 2918–2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pusterla N., Pesavento P. A., Leutenegger C. M., Hay J., Lowenstine L. J., Durando M. M., Magdesian K. G.2002. Disseminated pulmonary adiaspiromycosis caused by Emmonsia crescens in a horse. Equine Vet. J. 34: 749–752. doi: 10.2746/042516402776250342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sigler L.2005. Adiaspiromycosis and other infections caused by Emmonsia species. pp. 809–824. In: Medical Mycology. Topley and Wilson’s Microbiology and Microbial Infections. 10th ed. (Merz, W. G. and Hay, R. J. eds.), Hodder Arnold, London. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taniyama H., Furuoka H., Matsui T., Ono T.1985. Two cases of adiaspiromycosis in the Japanese pika (Ochotona hyperborea yesoensis Kishida). Jpn. J. Vet. Sci. 47: 139–142. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.47.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.