Abstract

Aims

Therapeutic approaches to treat familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), which is characterized by depressed sarcomeric tension and susceptibility to Ca2+-related arrhythmias, have been generally unsuccessful. Our objective in the present work was to determine the effect of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) biased ligand, TRV120023, on contractility of hearts of a transgenic mouse model of familial DCM with mutation in tropomyosin at position 54 (TG-E54K). Our rationale is based on previous studies, which have supported the hypothesis that biased G-protein-coupled receptor ligands, signalling via β-arrestin, increase cardiac contractility with no effect on Ca2+ transients. Our previous work demonstrated that the biased ligand TRV120023 is able to block angiotensin-induced hypertrophy, while promoting an increase in sarcomere Ca2+ response.

Methods and results

We tested the hypothesis that the depression in cardiac function associated with DCM can be offset by infusion of the AT1R biased ligand, TRV120023. We intravenously infused saline, TRV120023, or the unbiased ligand, losartan, for 15 min in TG-E54K and non-transgenic mice to obtain left ventricular pressure–volume relations. Hearts were analysed for sarcomeric protein phosphorylation. Results showed that the AT1R biased ligand increases cardiac performance in TG-E54K mice in association with increased myosin light chain-2 phosphorylation.

Conclusion

Treatment of mice with an AT1R biased ligand, acting via β-arrestin signalling, is able to induce an increase in cardiac contractility associated with an increase in ventricular myosin light chain-2 phosphorylation. AT1R biased ligands may prove to be a novel inotropic approach in familial DCM.

Keywords: Angiotensin II type 1 receptor, Cardiac sarcomeres, Contractility, Inotropic agent, Losartan

1. Introduction

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), one of the leading causes of heart failure, is characterized by wall thinning associated with depressed systolic and diastolic function. Once symptoms develop, there is a poor prognosis with a lack of therapeutic approaches to address the diminished cardiac function. Although the development of novel therapies for DCM remains a significant challenge, an important clue to the triggers leading to and sustaining DCM is the linkage of the disorder to mutations in sarcomeric proteins resulting in reduced myofilament response to Ca2+.1–5 Moreover, maladaptive signalling associated with models of acquired DCM also involves depressed myofilament response to Ca2+.6–8 Thus, an objective of our experiments has been to test therapeutic interventions that increase myofilament response to Ca2+.

We9 have recently reported that the biased ligand TRV120023 interacting with the angiotensin II (Ang II) type 1 receptor (AT1R) enhances myofilament Ca2+ response. This result indicated a novel therapeutic approach for treating DCM. Biased ligands, as with unbiased ligands, effectively block the maladaptive G-protein signalling cascades of the renin–angiotensin system by acting as AT1R blockers (ARBs). However, unlike unbiased ligands, AT1R biased ligands preserve and promote signalling via the scaffolding protein, β-arrestin.10 The biased ligands TRV120023 and TRV120027 acting via β-arrestin have been reported to increase contractility of isolated myocytes with no change in Ca2+ transients.11–14 Based on these findings, we9 previously compared the effects of the unbiased ligand, losartan, and the biased ligand, TRV120023, on the response of rat hearts to chronic infusion of Ang II.9 Our data demonstrated that while both losartan and TRV120023 blocked hypertrophic signalling in this model, TRV120023 was more effective in preserving the increased myofilament Ca2+ response induced by Ang II.

In experiments reported here, we have tested the effect of administration of TRV120023 on in situ cardiac contractility of a transgenic mouse model of familial DCM expressing a mutant tropomyosin (TG-E54K) with reduced myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. We4 have previously reported that this model demonstrates a significant DCM phenotype with impaired left ventricular fractional shortening measured by echocardiography as well as impaired systolic and diastolic functions in work-performing hearts. Studies with detergent extracted (skinned) fibre bundles from controls and TG-E54K hearts revealed a significant depression of response to Ca2+ and maximum tension generation.5 In the present experiments, we intravenously (IV) infused TRV120023 or losartan in TG-E54K mice and measured left ventricular pressure–volume (PV) loops. Analysis of the PV loops showed an increase in contractility with TRV120023 but not with losartan. Determination of sarcomeric protein phosphorylation showed an increase in regulatory myosin light chain (MLC2) phosphorylation, an effect previously reported to increase myofilament Ca2+ response.15–17 Thus, our data indicate that promotion of β-arrestin signalling by biased ligands may represent a novel therapeutic intervention to improve cardiac function in DCM.

2. Methods

2.1. Mice

We used male and female 4-month-old non-transgenic (NTG) and TG-E54K mice in our experiments. All mice were in the FVBN background. All protocols were in accordance with guidelines of and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Illinois at Chicago and National Institutes of Health. We previously described the methods of TG-E54K mice generation and characterization.4

2.2. Drugs

We used saline, TRV120023, and losartan for IV infusion in NTG and TG-E54K mice. TRV120023 was synthesized by Genescript (Piscataway, NJ, USA), characterized at Trevena Inc. (King of Prussia, PA, USA), and stored at −25°C. Before each experiment, TRV120023 was solubilized with saline to obtain the desired concentration and infused (100 μg/kg/min); dose was determined based on previous experiments.11 Losartan was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and stored per manufacturer's instructions. Losartan dose was 5 mg/kg/min as determined from previous experiments.11

2.3. Pressure volume data

We employed previously described methods to obtain in vivo haemodynamic measurements of PV relations using a conductance catheter.18 Mice were anaesthetized with 3% isoflurane and 100% oxygen inhaled in a closed anaesthesia chamber. A plane of anaesthesia for surgery was monitored by toe pinch and regulated by delivery of 1% isoflurane administered through a nose cone with 100% oxygen. Mice were instrumented with a rectal temperature probe connected to a thermally controlled table to maintain body temperature at 37°C. A tracheotomy was performed and an intubation cannula was inserted into the trachea and secured with a suture. The cannula was connected to miniature mechanical ventilator and mixture of 1% isoflurane and 100% oxygen was administered. Right common carotid artery was isolated; the distal end tied off with 6-0 prolene sutures, and the artery was cannulated with a 1.4 F Micro-Tip ultra-miniature PV transducer (model SPR-839; Millar, Houston, TX, USA). The transducer was advanced retrogradely down the right carotid artery, into the aorta, through the aortic valve into the left ventricle (LV). For occlusion data, the inferior vena cava was accessed above the diaphragm through a buttonhole created in the abdominal wall just below the sternum. Before and during the saline, TRV120023, or losartan infusions, heart rate (HR) and LV pressures and volumes were continuously monitored and all haemodynamic data were digitally recorded on LabChart Pro software (v. 8.0; ADI Instruments). Inferior vena cava occlusions were obtained before and then 15 min following saline, TRV120023, or losartan infusion. To gain venous access for IV infusions, the right external jugular vein was isolated, the distal end was tied off, and the proximal end was catheterized with stretched PE-10 tubing. This tubing was connected to a 100 μL Hamilton glass syringe mounted on a micro infusion pump (model 355, Sage Instruments, Cambridge, MA, USA), which allowed for precise delivery of saline, TRV120023, or losartan for the duration of 15 min at 1 μL/min infusion rate. At the end of all experiments, the PV catheter was removed from the LV, and the heart was excised, quickly weighed, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for analytical studies.

2.4. Pro-Q Diamond Stain for assessment of myofilament phosphorylation

Myofibrils were prepared from 20–30 mg of liquid nitrogen-frozen left ventricle as previously described but with minor modifications.19 The samples were homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer in standard relax buffer (10 mM Imidazole pH 7.2, 75 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, and 1 mM NaN3) with 1% (v/v) Triton X-100.20 The pellets were centrifuged and homogenized again in the same buffer. After centrifugation, the pellets were washed once in standard relax buffer to remove the Triton X-100. The pellets were then solubilized in sample buffer (8 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 0.05 M Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 75 mM DTT, 3% SDS, 0.05% bromophenol blue)21 and homogenized again. All standard relax buffers contained both protease (Sigma no. P8340) and phosphatase (Calbiochem no. 524624) inhibitors at a 1:100 dilution. An RCDC assay kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to determine the protein concentration of the samples. Myofibrillar protein (10 µg) total was loaded into each lane of a 12% SDS–PAGE22 gel and run at constant 200 V. After 90 min, the gel was placed in a fix solution (50% methanol, 10% acetic acid) overnight and then stained with PRO-Q Diamond Stain (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. The gel was imaged on a Typhoon 9410 imager using a CY3 filter set and subsequently stained with Coomassie blue to visualize actin bands. Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageQuant TL (GE Healthcare) to determine protein band intensities obtained from Pro-Q Diamond and Coomassie blue-stained images. Actin bands from Coomassie blue-stained images were used as a loading control to normalize protein bands from Pro-Q Diamond stained images on Microsoft Excel sheath.

2.5. Western blots for MYPT1 phosphorylation

Ventricular lysate (20.0 μg) was electrophoresed on 12% acrylamide, denaturing gels at 200 V, constant voltage, for 1 h and 15 min in 1X-Tris-Glycine Run Buffer. Gels were then transferred onto 0.2 μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane for 2 h at 25 V, constant voltage, in 1X-CAPS, pH 11.0. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk dissolved in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T), and then incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibody for p-MYPT1 (Upstate Biotechnologies, Lake Placid, NY, USA), 1:4000, and total MYPT1 (BD Transduction Labs, San Jose, CA, USA), 1:4000. Following incubation, membranes were washed for 30 min in TBS-T and then incubated in secondary goat anti-mouse antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), 1:50 000 for p-MYPT1 and goat anti-rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling Technologies, Boston, MA, USA), 1:40 000 for total MYPT1 conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were then washed for 30 min in TBS-T and developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Clarity, BioRad) on a ChemiDoc XRS+ imager (BioRad). Band densities were analysed using ImageLab software (BioRad). All blots were analysed using ImageLab software and normalized to total protein.

2.6. Statistical methods

All results were presented as means ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was conducted using an unpaired t-test for the baseline comparisons between NTG and TG-E54K mice. A two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparison test was used for saline, TRV120023, or losartan effect in comparison with baseline PV data, and a Tukey's multiple comparison test was used for comparing the three groups (saline, TRV120023, and losartan). Proteomics data were analysed using a two-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test. Probability value P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. TG-E54K mouse hearts have cardiac dysfunction at baseline

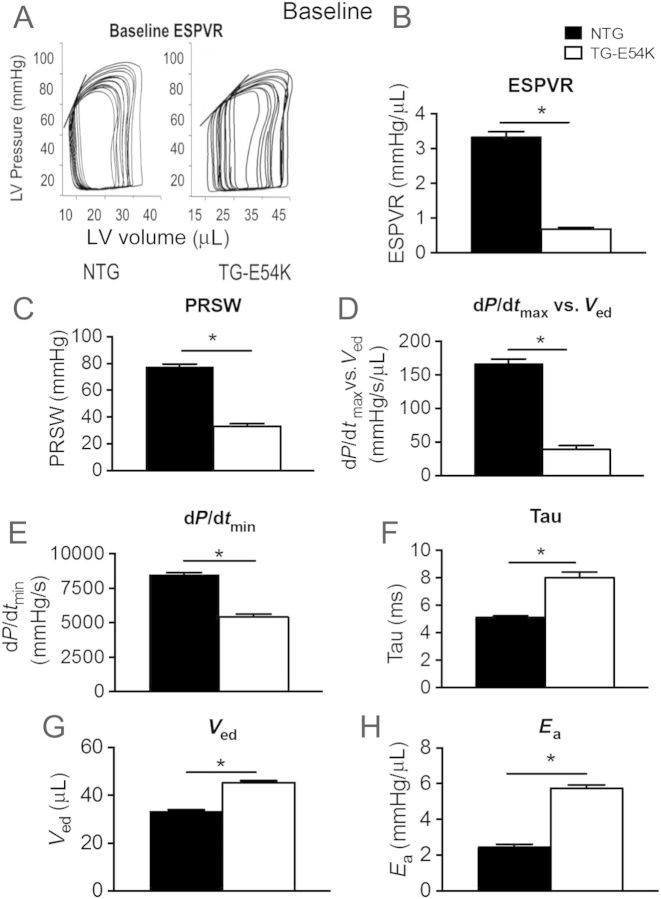

Analysis of baseline PV data demonstrated that TG-E54K mice hearts have reduced contractility, diastolic dysfunction, and increased afterload (Figure 1). The data confirmed a baseline reduction in contractility, which we previously reported.4 Compared with NTG controls, TG-E54K hearts showed a decrease in the following: load-independent contractility measures such as end-systolic pressure–volume relationship (ESPVR) (Figure 1A and B), preload recruitable stroke work (PRSW) (Figure 1C), and the relation between LV pressure rise during isovolumic contraction and end-diastolic volume (dP/dtmax vs. Ved) (Figure 1D). Baseline diastolic parameters such as lower LV pressure drop during isovolumic relaxation (dP/dtmin) (Figure 1E) and higher isovolumic relaxation time constant (τ) (Figure 1F) in TG-E54K mice hearts compared with NTG mice hearts indicated diastolic dysfunction of TG-E54K mice hearts. In addition, baseline PV data showing greater Ved in TG-E54K compared with NTG (Figure 1G) hearts were consistent with DCM morphology of TG-E54K mice shown by echocardiography in a previous study.4 PV data were also consistent with TG-E54K mice having a relatively high arterial elastance (Ea), a measure of afterload, compared with NTG mice hearts at baseline (Figure 1H).

Figure 1.

Decreased baseline cardiac function of TG-E54K hearts compared with NTG controls. (A) Representative pressure–volume (PV) loops and (B) histogram show decreased end-systolic PV relation (ESPVR) slope in TG-E54K compared with NTG hearts. TG-E54K hearts have (C) lower preload recruitable stroke work (PRSW) and (D) lower dP/dtmax vs. end-diastolic volume (Ved). Diastolic function in the TG-E54K compared with NTG is illustrated by (E) depression in dP/dtmin, (F) an increase in the relaxation time constant, τ, and (G) an increase in Ved. (H) Arterial elastance (Ea), an afterload measure is increased in TG-E54K mice. n = 19 in each group, data are shown as means ± SEM. Unpaired two-tail t-test was used for statistical analysis. *P < 0.05 compare with NTG controls.

3.2. Cardiac contractility is increased with TRV120023, but decreased with losartan infusion

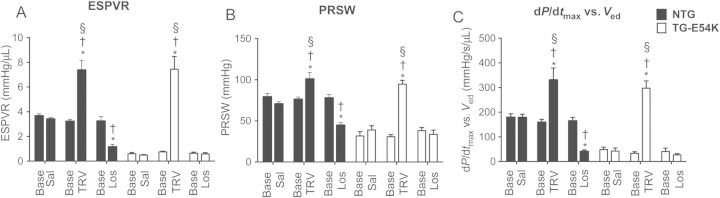

As illustrated by the PV loop data in Figure 2, there was an increase in contractility following infusion of TRV120023 in both TG-E54K and NTG hearts. Following TRV120023 infusion in TG-E54K hearts, there was a significant increase in ESPVR, a load-independent measure of contractility (Figure 2A). ESPVR was also increased with TRV120023 in NTG hearts. Other load-independent contractility measures such as PRSW (Figure 2B) and dP/dtmax vs. Ved (Figure 2C) were also increased in TG-E54K and NTG mouse hearts during TRV120023 infusion. In fact, TRV120023 restored contractility of TG-E54K hearts to the same level as values in the NTG hearts after TRV120023 infusion. In contrast to TRV120023, losartan infusion induced a decrease in ESPVR (Figure 2A), PRSW (Figure 2B), and dP/dtmax vs. Ved (Figure 2C) in NTG hearts. Losartan decreased contractility in NTG mice hearts to the same level as baseline values in TG-E54K hearts.

Figure 2.

Histograms summarize changes in load-independent cardiac contractility measures, following saline, TRV120023, or losartan infusion in TG-E54K and NTG mice hearts. (A) ESPVR is enhanced with TRV120023 in NTG and TG-E54K hearts and depressed with losartan in NTG hearts. Other contractility measures (B) preload recruitable stroke work (PRSW) and (C) left ventricle pressure rise during isovolumic contraction plotted against end-diastolic volume (dP/dtmax vs. Ved) are increased compared with baseline in both TG-E54K and NTG hearts with TRV120023, whereas they are decreased in NTG with losartan. Note that no difference in contractility between NTG and TG-E54K following infusion of TRV120023. n = 5 in saline and losartan-infused TG-E54K, n = 6 in saline-infused NTG, n = 9 in losartan and TRV120023-infused NTG and TRV120023-infused TG-E54K. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak's and Tukey's multiple comparison tests were used for statistical analysis to compare the effect of saline, TRV120023, or losartan with baseline and to compare effects of saline, TRV120023, and losartan with each other, respectively. *P < 0.05 compared with baseline within the same group. †P < 0.05 compared with saline infusion in respective group. §P < 0.05 compared with losartan infusion in respective group.

3.3. TRV120023 and losartan induce changes in other haemodynamic parameters of TG-E54K and NTG mice hearts

As summarized in Table 1, which describes haemodynamic changes in NTG mouse hearts, TRV120023 decreased stroke work (SW) and losartan decreased developed pressure (Pdev) in NTG mice hearts. dP/dtmax was lowered in NTG mice hearts following both TRV120023 and losartan infusion.

Table 1.

Haemodynamic parameters by pressure–volume analysis in non-transgenic mice in response to infusion of saline, TRV120023, or losartan

| Baseline | Saline | Baseline | TRV120023 | Baseline | Losartan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW, mmHg μL | 2253.7 ± 136.5 | 2231.7 ± 111.1 | 2050.7 ± 108.2 | 1670.2 ± 25.3* | 2174.3 ± 96.5 | 2034.0 ± 59.7 |

| CO, μL | 14 221.1 ± 804.7 | 14 811.0 ± 968.7 | 12 276.0 ± 372.4 | 11 956.4 ± 657.2 | 11 455.0 ± 640.4 | 12 932.7 ± 873.8 |

| SV, μL | 23.2 ± 1.2 | 22.8 ± 1.4 | 20.3 ± 0.7 | 20.4 ± 1.1 | 19.3 ± 1.2 | 22.2 ± 1.5 |

| Ves, μL | 10.6 ± 0.1 | 11.4 ± 0.6 | 11.7 ± 0.8 | 12.9 ± 0.8 | 14.7 ± 1.1 | 14.3 ± 1.2 |

| Ved, μL | 33.9 ± 1.1 | 34.3 ± 1.2 | 32.0 ± 0.7 | 33.3 ± 0.9 | 34.1 ± 1.6 | 36.5 ± 1.2 |

| Pdev, mmHg | 87.1 ± 2.7 | 85.5 ± 2.4 | 80.1 ± 1.6 | 73.8 ± 2.1 | 83.3 ± 1.9 | 71.7 ± 2.2* |

| Pes, mmHg | 69.1 ± 2.9 | 73.1 ± 2.3 | 65.5 ± 1.8 | 61.1 ± 2.4 | 74.1 ± 2.5 | 67.6 ± 2.5 |

| Ped, mmHg | 7.0 ± 0.5 | 8.4 ± 0.4 | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 8.4 ± 0.6 | 9.9 ± 0.7 | 9.4 ± 0.3 |

| HR, bpm | 612.5 ± 16.0 | 648.1 ± 9.4 | 604.8 ± 9.8 | 587.4 ± 13.8 | 595.5 ± 8.6 | 582.3 ± 10.1 |

| Ea, mmHg/μL | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.4 |

| EF, % | 68.4 ± 1.3 | 66.4 ± 2.2 | 63.7 ± 2.1 | 61.2 ± 2.5 | 56.8 ± 2.5 | 60.7 ± 3.3 |

| dP/dtmax, mmHg/s | 11 976.7 ± 618.0 | 11 056.3 ± 543.7 | 10 104.0 ± 455.6 | 7988.8 ± 287.4* | 9786.8 ± 397.4 | 6271.9 ± 327.7* |

| ESPVR, mmHg/μL | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 7.4 ± 0.8* | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.2* |

| PRSW, mmHg | 79.2 ± 4.1 | 70.6 ± 2.6 | 76.1 ± 2.9 | 100.8 ± 8.1* | 77.8 ± 4.3 | 44.7 ± 3.2* |

| dP/dtmax vs. Ved, mmHg/s/μL | 179.0 ± 14.7 | 178.3 ± 13.5 | 158.9 ± 12.2 | 330.6 ± 48.6* | 164.8 ± 14.6 | 40.3 ± 6.8* |

| EDPVR, mmHg/μL | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| dP/dtmin, mmHg/s | −9095.3 ± 243.0 | −9093.7 ± 299.5 | −8208.1 ± 284.5 | −7757 ± 213.7 | −8253.3 ± 352.0 | −8094.7 ± 255.6 |

| τ, ms | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.1 |

SW is decreased with TRV120023. Pdev is decreased with losartan. dP/dtmax is decreased with TRV120023 and losartan. ESPVR, PRSW, and dP/dtmax vs. Ved are increased with TRV120023 and decreased with losartan. n = 6 in saline-infused NTG mice. n = 9 in losartan and TRV120023-infused NTG mice. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis.

SW, stroke work; CO, cardiac output; SV, stroke volume; Ves, end-systolic volume; Ved, end-diastolic volume; Pdev, developing pressure; Pes, end-systolic pressure; Ped, end-diastolic pressure; HR, heart rate; Ea, arterial elastance; EF, ejection fraction; dP/dtmax, raise in left ventricle pressure during isovolumic contraction; ESPVR, end-systolic pressure–volume relationship; PRSW, preload recruitable stroke work; dP/dtmax vs. Ved, dP/dtmax plotted against Ved; EDPVR, end-diastolic pressure–volume relationship; dP/dtmin, left ventricle pressure drop during isovolumic relaxation; τ, isovolumic relaxation time constant.

*P < 0.05 compared with baseline of same group.

As summarized in Table 2, which describes haemodynamic changes in TG-E54K mouse hearts, TRV120023 infusion decreased SW, end-diastolic volume (Ved), end-systolic volume (Ves), end-diastolic pressure (Ped), end-systolic pressure (Pes), and Pdev. Stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO), and ejection fraction (EF) were increased with TRV120023 infusion. Ea, a measure of afterload, was decreased following TRV120023 and losartan infusion. The decrease in afterload in TG-E54K with TRV120023 was such that there was no difference in Ea in TG-E54K after TRV120023 infusion compared with NTG at baseline (Table 1). Similarly, losartan infusion decreased SW, Pdev, and Pes.

Table 2.

Haemodynamic parameters by pressure–volume analysis in transgenic mice in response to infusion of saline, TRV120023, or losartan

| Baseline | Saline | Baseline | TRV120023 | Baseline | Losartan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW, mmHg μL | 2864.0 ± 30.2 | 2827.9 ± 39.3 | 3060.8 ± 82.9 | 2100.8 ± 80.1* | 3158.0 ± 123.6 | 2710.2 ± 175.3* |

| CO, μL | 10 867.0 ± 1063.0 | 10 135.7 ± 1532.7 | 10 500.4 ± 831.8 | 17 501.9 ± 889.9* | 12 291.0 ± 1106.9 | 10 468.1 ± 909.8 |

| SV, μL | 19.3 ± 2.2 | 17.9 ± 2.4 | 17.8 ± 1.3 | 30.4 ± 2.3* | 21.0 ± 1.6 | 18.8 ± 1.9 |

| Ves, μL | 24.9 ± 1.7 | 26.0 ± 2.4 | 26.7 ± 1.0 | 16.6 ± 0.9* | 27.1 ± 1.3 | 30.0 ± 1.9 |

| Ved, μL | 44.1 ± 1.3 | 43.4 ± 1.0 | 44.5 ± 1.1 | 47.0 ± 1.3 | 48.2 ± 1.3 | 48.8 ± 1.8 |

| Pdev, mmHg | 73.2 ± 5.9 | 74.5 ± 5.1 | 81.2 ± 2.7 | 73.1 ± 2.2* | 85.0 ± 2.1 | 69.6 ± 0.7* |

| Pes, mmHg | 75.3 ± 5.8 | 76.2 ± 4.7 | 87.4 ± 2.6 | 72.0 ± 2.4* | 88.9 ± 3.1 | 68.9 ± 2.0* |

| Ped, mmHg | 8.5 ± 1.7 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 11.7 ± 1.5 | 8.1 ± 0.7* | 9.2 ± 2.2 | 6.9 ± 0.7 |

| HR, bpm | 568.6 ± 17.2 | 562.1 ± 9.1 | 591.3 ± 10.9 | 577.2 ± 11.9 | 584.0 ± 26.4 | 560.1 ± 11.3 |

| Ea, mmHg/μL | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.6* | 5.7 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.2* |

| EF, % | 43.4 ± 4.4 | 41.2 ± 5.2 | 39.7 ± 2.4 | 64.5 ± 21* | 43.5 ± 2.9 | 38.5 ± 3.7 |

| dP/dtmax, mmHg/s | 5761.6 ± 996.0 | 6398.8 ± 1012.0 | 5792.8 ± 326.9 | 5376.4 ± 330.0 | 6902.6 ± 255.3 | 5122.6 ± 277.5 |

| ESPVR, mmHg/μL | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 1.0* | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| PRSW, mmHg | 31.7 ± 5.2 | 38.9 ± 5.3 | 30.8 ± 2.6 | 84.6 ± 8.6* | 38.1 ± 3.8 | 33.6 ± 5.3 |

| dP/dtmax vs. Ved, mmHg/s/μL | 49.2 ± 9.2 | 42.5 ± 12.4 | 33.3 ± 6.7 | 297.4 ± 29.3* | 40.6 ± 14.1 | 27.0 ± 5.0 |

| EDPVR, mmHg/μL | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| dP/dtmin, mmHg/s | −5365.2 ± 475.9 | −5407 ± 294.0 | −5255.2 ± 381.0 | −4987.6 ± 386.3 | −5734.8 ± 182.7 | −5419.2 ± 226.6 |

| τ, ms | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 8.2 ± 0.7 | 8.2 ± 0.8 | 7.8 ± 0.7 | 8.2 ± 0.6 |

SW is decreased with TRV120023 and losartan. CO and SV are increased with TRV120023. Ves is decreased with TRV120023. Pdev is decreased with TRV120023 and losartan. Pes is decreased with TRV120023 and losartan. Ped is decreased with TRV120023. Ea is decreased with TRV120023 and losartan. EF is increased with TRV120023. ESPVR, PRSW, and dP/dtmax vs. Ved are increased with TRV120023. n = 5 in saline and losartan-infused TG-E54 K mice. n = 9 in TRV120023-infused TG-E54 K mice. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis.

SW, stroke work; CO, cardiac output; SV, stroke volume; Ves, end-systolic volume; Ved, end-diastolic volume; Pdev, developing pressure; Pes, end-systolic pressure; Ped, end-diastolic pressure; HR, heart rate; Ea, arterial elastance; EF, ejection fraction; dP/dtmax, raise in left ventricle pressure during isovolumic contraction; ESPVR, end-systolic pressure–volume relationship; PRSW, preload recruitable stroke work; dP/dtmax vs. Ved; dP/dtmax plotted against Ved; EDPVR, end-diastolic pressure–volume relationship; dP/dtmin, drop in left ventricle pressure during isovolumic relaxation; τ, isovolumic relaxation time constant.

*P < 0.05 compared with baseline of same group.

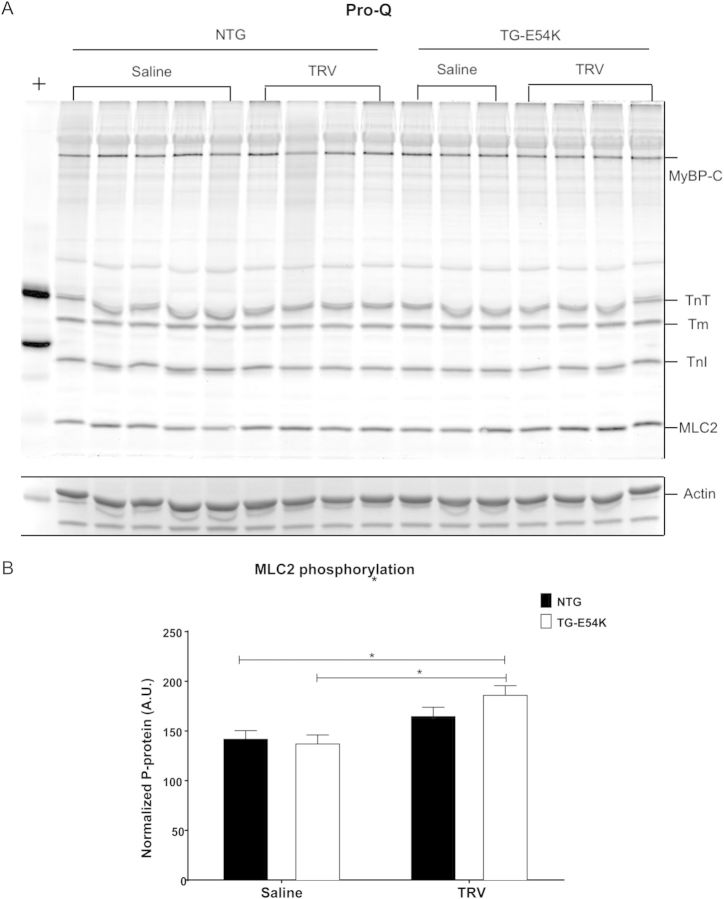

3.4. MLC2 phosphorylation is increased with TRV120023 in TG-E54K mice

Pro-Q analysis demonstrated increased MLC2 phosphorylation in TG-E54K mice hearts after TRV120023 infusion compared with saline infusion in TG-E54K and NTG mice (Figure 3). TRV120023 did not alter phosphorylation of myosin-binding protein-C (MyBP-C), troponin T (TnT), tropomyosin (Tm), and troponin I (TnI). We found no changes in myofilament protein phosphorylation with either saline or losartan infusion. Moreover, there was no significant change in MLC2 phosphorylation in NTG hearts treated with TRV120023.

Figure 3.

Analysis of myofilament phosphorylation by Pro-Q Diamond stain shows increased myosin light chain-2 (MLC2) phosphorylation in transgenic (TG-E54K) mice hearts with TRV120023. (A) Pro-Q Diamond stained image is specific for phosphorylated myofilament proteins, myosin-binding protein C (MyBP-C), troponin T (TnT), tropomyosin (Tm), troponin I (TnI), and MLC2. A region of interest from a Coomassie gel shows actin, which is used for normalization. + represents Peppermint stick standard. (B) Histogram showing normalized phosphorylated MLC2. n = 3 for NTG TRV120023, n = 4 for all remaining groups. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA test with Tukey's post hoc analysis for multiple comparisons was used for statistical analysis. *P < 0.05 compared with saline infusion.

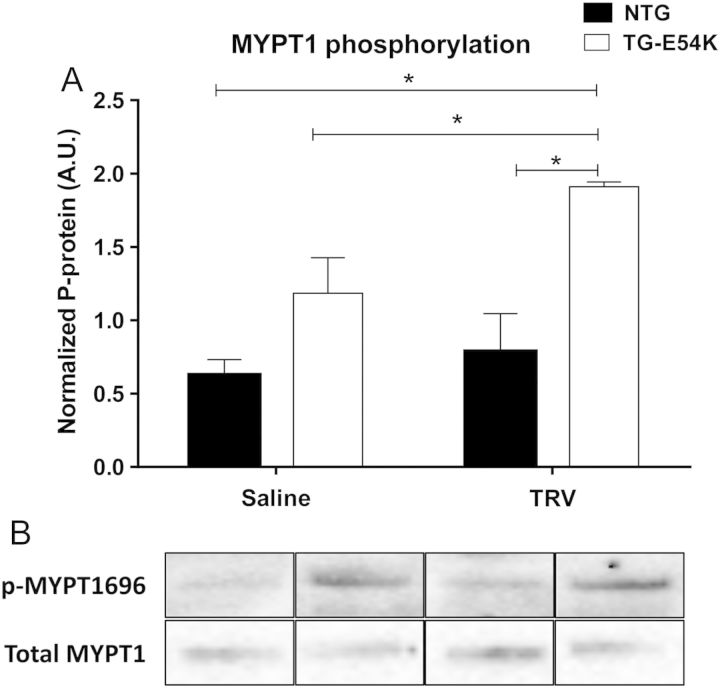

3.5. MYPT1 phosphorylation is increased with TRV120023

Experimental studies done in vascular smooth muscle have implicated β-arrestin signalling in altering MLC2 phosphorylation.23 We, therefore, tested whether treatment of hearts with TRV120023 increased phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T-695, a site previously demonstrated to induce inhibition of phosphatase activity and thereby increase MLC2 phosphorylation.24 As illustrated in Figure 4, western blot analysis showed increased MYPT1 phosphorylation in TG-E54K mouse hearts after TRV120023 infusion compared with saline infusion in NTG and TG-E54K and TRV120023 infusion in NTG mice. MYPT1 phosphorylation was unchanged with TRV120023 in NTG mice hearts.

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis shows increased T-696 phosphorylation of myosin phosphatase target (MYPT1), a regulatory subunit of myosin light chain phosphatase, in DCM hearts (TG-E54K) with TRV120023. (A) Histogram showing normalized phosphorylated MYPT1. (B) Western blot image is specific for phosphorylated and total MYPT1. Total MYPT1 was used for normalization. n = 3 in saline-infused NTG, n = 4 in TRV120023-infused TG-E54K, n = 4 in TRV120023-infused NTG and TG-E54K. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA test with Tukey's post hoc for multiple comparisons was used for statistical analysis. *P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Our data are the first to report that acute administration of a biased ligand acting as an ARB and promoting β-arrestin signalling induces an increase in cardiac contractility in a mouse model of familial DCM. Our data also support the hypothesis that biased signalling of the AT1R promotes downstream β-arrestin signalling cascades that modify the sarcomeres via an increase in MLC2 phosphorylation. Although there are inotropic agents that affect cardiac contractility by modifying sarcomeres downstream of Ca2+-binding, to the best of our knowledge, none of these agents act via increasing MLC2 phosphorylation.

4.1. AT1R biased ligand as a novel inotropic agent in DCM

We think the results of our study of the inotropic effects of a biased ligand, which has demonstrated efficacy and safety in humans,25 significantly improve the potential for treatment of DCM. Heart failure induced by DCM remains a leading cause of mortality.26 Clinical trials with various inotropic agents have not produced favourable outcomes in DCM due to increased myocardial energy expenditure and increased risk of adverse effects such as arrhythmias and myocardial cell death associated with Ca2+ toxicity.17,27 Currently approved inotropes include glycosides, adrenergic agonists, and phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors, which increase cardiac contractility primarily by Ca2+ mobilization either with or without an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate.17,28 Hence, their role in DCM remains limited and palliative.27 An advantage of the effects of a biased ARB is that they are likely to occur without an increase in intracellular Ca2+ transients and myocardial energy expenditure, while increasing sarcomeric response to Ca2+ and blocking the maladaptive effects of Ang II at the AT1R. Moreover, our data show that biased (TRV120023) and unbiased (losartan) ARBs share the favourable effect of decreasing afterload in DCM. Other inotropic agents exist that modify Ca2+ response of the sarcomeres, without Ca2+ mobilization. These Ca2+ sensitizers or sarcomere activators include pimobendan and levosimendan, which enhance myofilament Ca2+ responses by interacting with troponin C in the thin filament regulatory complex.17,28 A concern with these agents is the potential for PDE inhibition, which may limit their use in DCM.28,29 Omecamtiv Mecarbil, a more recently developed inotropic agent, acts as a myosin activator and is currently undergoing clinical trials.16 As with the biased ARB, Omecamtiv Mecarbil increases contractility without mobilizing Ca2+.11,30 To our knowledge, Omecamtiv Mecarbil has not been tested with regard to its therapeutic efficacy in familial DCM. Further investigation is required for determination of the general applicability of biased ligands in other models with depressed myofilament Ca2+ response.

Interestingly, we found that the unbiased ARB, losartan, induced a decrease in contractility in controls, but not in TG-E54K DCM hearts. These differences between a biased angiotensin receptor modulator and unbiased ARB suggest that signalling via the AT1R is likely to be different in the models. We speculate that the lack of a negative effect on function in the DCM animals is due to the fact these hearts are significantly functionally depressed to such an extent that negative effects of losartan are not evident. On the other hand in the non-transgenic controls, contractility is not impaired; signalling is likely to be different at the AT1R and apparently vulnerable to effects of losartan.

4.2. β-Arrestin-mediated increases in cardiac contractility is dependent on MLC2 phosphorylation

Our data demonstrate that there is an increase in MLC2 phosphorylation associated with the enhanced contractility following infusion of the β-arrestin-biased ligand in hearts of TG-E54K mice. There is extensive evidence15,31 that in the short term increases in MLC2 phosphorylation may increase contractility by modulating myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity.32–34 MLC2 is located at the S1-S2 junction of the myosin heavy chain in a position poised to control the interaction of cross-bridges with the thin filament. Evidence indicates that phosphorylation of MLC2 influences the stiffness of the cross-bridges35 as well as the radial disposition of the myosin heads with respect to the thick filament backbone.36 Both of these mechanisms37 are expected to increase the transition of cross-bridges to strongly bound and force generating states. It is interesting to note that persistent relatively low turnover of MLC2 phosphorylation occurring in diverse transgenic models induces a DCM phenotype.15,31,38

MLC2 phosphorylation is carried out primarily by cardiac-specific MLC2 kinase (MLCK)38,39 and is regulated by MLC2 phosphatase (MLCP) by dephosphorylating MLC2.40,41 Cardiac-specific MLCK, as opposed to smooth muscle MLCK, can phosphorylate MLC2 independent of Ca2+/calmodulin39 and our data demonstrated that β-arrestin-biased ligand, which acts independently of Ca2+, increases MLC2 phosphorylation, suggesting β-arrestin-mediated MLC2 phosphorylation in the heart may be MLCK mediated. Here, we have shown that TRV120023 increases MYPT1 phosphorylation in TG-E54K mice providing a mechanism for the increase in MLC2 phosphorylation we observed; however, this finding was not extended to NTG TRV120023 animals. In light of this evidence, we hypothesize that β-arrestin signalling pathways are likely to affect phosphorylation of MLC2 at many levels. TG-E54K mice may have a variable response to TRV120023 in response to their chronic condition. Future work characterizing the involvement of β-arrestin signalling pathways in regulating MLC2 phosphorylation will increase our understanding of this observation.

In view of evidence that MLC2 of smooth muscle is phosphorylated by β-arrestin signalling involving MYPT1, we tested whether treatment of hearts with TRV120023 increased phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T-695, a site previously reported to induce inhibition of phosphatase activity and therefore increase MLC2 phosphorylation. Our finding that TRV120023 induced an increase in phosphorylation of T-695 in DCM but not in NTG hearts supports our data on determination of MLC2 phosphorylation and further indicates differential signalling occurring in controls and TG-E54K hearts. Earlier studies determined that a RhoA/ROCK/MLCK regulates membrane blebbing in an AT1-R/β-arrestin2 pathway.42 RhoA/ROCK has also been linked to MYPT-T695 phosphorylation in cardiac41 and smooth muscles.43 Hence, it is plausible that β-arrestin-mediated MYPT phosphorylation is RhoA dependent. It will be interesting to determine whether β-arrestin activated RhoA/ROCK regulates MLC2 phosphorylation by both the activation of MLCK and inhibition of MLCP in heart.

5. Conclusion

In previous studies, acute effects of selective promotion of β-arrestin signalling in mice demonstrated an enhanced contractility as determined with PV loop analysis as well as an expected reduction in mean arterial pressure associated with the block of G-protein signalling.12 Our data show that these two responses are obtained in a model of DCM and may be of therapeutic benefit in this condition in humans. DCM remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality despite the available guideline-directed medical therapy. We have demonstrated that novel AT1R biased ligands that increase cardiac contractility, without mobilizing Ca2+, may be a potential inotropic agent with favourable haemodynamic changes in DCM. Our results further suggest that the inotropic potential of AT1R biased ligand is due to modification of a myosin-bound regulatory thick filament protein, MLC2. Further studies are needed to elucidate the signalling cascade by which β-arrestin downstream signalling leads to MLC2 phosphorylation and increased cardiac contractility.

Conflict of interest: C.L.C. and J.D.V. are employees of Trevena Inc., a clinical stage biopharmaceutical company focused on discovering and developing biased ligands to deliver the next generation of GPCR targeted medicines; R.J.S. is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Cytokinetics, Inc.

Funding

Support was obtained from The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institute of Health [T32 HL07692-21-25 to M.T., R.T.D., and P.T.M.; PO1 HL 062426 (Project 1 and Cores B & C)] to R.J.S. and American Heart Association 15PRE22180010 to D.M.R.

References

- 1.Lakdawala NK, Dellefave L, Redwood CS, Sparks E, Cirino AL, Depalma S, Colan SD, Funke B, Zimmerman RS, Robinson P, Watkins H, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, McNally EM, Ho CY. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy caused by an alpha-tropomyosin mutation: the distinctive natural history of sarcomeric dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du CK, Morimoto S, Nishii K, Minakami R, Ohta M, Tadano N, Lu QW, Wang YY, Zhan DY, Mochizuki M, Kita S, Miwa Y, Takahashi-Yanaga F, Iwamoto T, Ohtsuki I, Sasaguri T. Knock-in mouse model of dilated cardiomyopathy caused by troponin mutation. Circ Res 2007;101:185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamisago M, Sharma SD, DePalma SR, Solomon S, Sharma P, McDonough B, Smoot L, Mullen MP, Woolf PK, Wigle ED, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Mutations in sarcomere protein genes as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1688–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajan S, Ahmed RP, Jagatheesan G, Petrashevskaya N, Boivin GP, Urboniene D, Arteaga GM, Wolska BM, Solaro RJ, Liggett SB, Wieczorek DF. Dilated cardiomyopathy mutant tropomyosin mice develop cardiac dysfunction with significantly decreased fractional shortening and myofilament calcium sensitivity. Circ Res 2007;101:205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Memo M, Leung MC, Ward DG, dos Remedios C, Morimoto S, Zhang L, Ravenscroft G, McNamara E, Nowak KJ, Marston SB, Messer AE. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy mutations uncouple troponin I phosphorylation from changes in myofibrillar Ca(2)(+) sensitivity. Cardiovasc Res 2013;99:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scruggs SB, Walker LA, Lyu T, Geenen DL, Solaro RJ, Buttrick PM, Goldspink PH. Partial replacement of cardiac troponin I with a non-phosphorylatable mutant at serines 43/45 attenuates the contractile dysfunction associated with PKCepsilon phosphorylation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2006;40:465–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roman BB, Goldspink PH, Spaite E, Urboniene D, McKinney R, Geenen DL, Solaro RJ, Buttrick PM. Inhibition of PKC phosphorylation of cTnI improves cardiac performance in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004;286:H2089–H2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldspink PH, Montgomery DE, Walker LA, Urboniene D, McKinney RD, Geenen DL, Solaro RJ, Buttrick PM. Protein kinase Cepsilon overexpression alters myofilament properties and composition during the progression of heart failure. Circ Res 2004;95:424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monasky MM, Taglieri DM, Henze M, Warren CM, Utter MS, Soergel DG, Violin JD, Solaro RJ. The beta-arrestin-biased ligand TRV120023 inhibits angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy while preserving enhanced myofilament response to calcium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013;305:H856–H866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Violin JD, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin-biased ligands at seven-transmembrane receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2007;28:416–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim KS, Abraham D, Williams B, Violin JD, Mao L, Rockman HA. Beta-arrestin-biased AT1R stimulation promotes cell survival during acute cardiac injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012;303:H1001–H1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Violin JD, DeWire SM, Yamashita D, Rominger DH, Nguyen L, Schiller K, Whalen EJ, Gowen M, Lark MW. Selectively engaging beta-arrestins at the angiotensin II type 1 receptor reduces blood pressure and increases cardiac performance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2010;335:572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tilley DG, Nguyen AD, Rockman HA. Troglitazone stimulates beta-arrestin-dependent cardiomyocyte contractility via the angiotensin II type 1A receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010;396:921–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajagopal K, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Stiber JA, Rosenberg PB, Premont RT, Coffman TM, Rockman HA, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin2-mediated inotropic effects of the angiotensin II type 1A receptor in isolated cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:16284–16289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheikh F, Lyon RC, Chen J. Getting the skinny on thick filament regulation in cardiac muscle biology and disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2014;24:133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNeice AH, McAleavey NM, Menown IB. Advances in clinical cardiology. Adv Ther 2014;31:837–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endoh M. Mechanisms of action of novel cardiotonic agents. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2002;40:323–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pacher P, Nagayama T, Mukhopadhyay P, Batkai S, Kass DA. Measurement of cardiac function using pressure-volume conductance catheter technique in mice and rats. Nat Protoc 2008;3:1422–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Layland J, Cave AC, Warren C, Grieve DJ, Sparks E, Kentish JC, Solaro RJ, Shah AM. Protection against endotoxemia-induced contractile dysfunction in mice with cardiac-specific expression of slow skeletal troponin I. FASEB J 2005;19:1137–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solaro RJ, Pang DC, Briggs FN. The purification of cardiac myofibrils with Triton X-100. Biochim Biophys Acta 1971;245:259–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yates LD, Greaser ML. Quantitative determination of myosin and actin in rabbit skeletal muscle. J Mol Biol 1983;168:123–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fritz JD, Swartz DR, Greaser ML. Factors affecting polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electroblotting of high-molecular-weight myofibrillar proteins. Anal Biochem 1989;180:205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simard E, Kovacs JJ, Miller WE, Kim J, Grandbois M, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin regulation of myosin light chain phosphorylation promotes AT1aR-mediated cell contraction and migration. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e80532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng J, Ito M, Ichikawa K, Isaka N, Nishikawa M, Hartshorne DJ, Nakano T. Inhibitory phosphorylation site for Rho-associated kinase on smooth muscle myosin phosphatase. J Biol Chem 1999;274:37385–37390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soergel DG, Subach RA, Cowan CL, Violin JD, Lark MW. First clinical experience with TRV027: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 2013;53:892–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dec GW, Fuster V. Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1564–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Writing Committee M, Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL, American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice G. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2013;128:e240–e327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kass DA, Solaro RJ. Mechanisms and use of calcium-sensitizing agents in the failing heart. Circulation 2006;113:305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nonaka M, Morimoto S, Murayama T, Kurebayashi N, Li L, Wang YY, Arioka M, Yoshihara T, Takahashi-Yanaga F, Sasaguri T. Stage-dependent benefits and risks of pimobendan in mice with genetic dilated cardiomyopathy and progressive heart failure. Br J Pharmacol 2015;172:2369–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malik FI, Hartman JJ, Elias KA, Morgan BP, Rodriguez H, Brejc K, Anderson RL, Sueoka SH, Lee KH, Finer JT, Sakowicz R, Baliga R, Cox DR, Garard M, Godinez G, Kawas R, Kraynack E, Lenzi D, Lu PP, Muci A, Niu C, Qian X, Pierce DW, Pokrovskii M, Suehiro I, Sylvester S, Tochimoto T, Valdez C, Wang W, Katori T, Kass DA, Shen YT, Vatner SF, Morgans DJ. Cardiac myosin activation: a potential therapeutic approach for systolic heart failure. Science 2011;331:1439–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scruggs SB, Solaro RJ. The significance of regulatory light chain phosphorylation in cardiac physiology. Arch Biochem Biophys 2011;510:129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Moss RL. Acceleration of stretch activation in murine myocardium due to phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain. J Gen Physiol 2006;128:261–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss RL, Fitzsimons DP. Myosin light chain 2 into the mainstream of cardiac development and contractility. Circ Res 2006;99:225–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olsson MC, Patel JR, Fitzsimons DP, Walker JW, Moss RL. Basal myosin light chain phosphorylation is a determinant of Ca2+ sensitivity of force and activation dependence of the kinetics of myocardial force development. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004;287:H2712–H2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khromov AS, Somlyo AV, Somlyo AP. Thiophosphorylation of myosin light chain increases rigor stiffness of rabbit smooth muscle. J Physiol 1998;512(Pt 2):345–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colson BA, Locher MR, Bekyarova T, Patel JR, Fitzsimons DP, Irving TC, Moss RL. Differential roles of regulatory light chain and myosin binding protein-C phosphorylations in the modulation of cardiac force development. J Physiol 2010;588:981–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheikh F, Ouyang K, Campbell SG, Lyon RC, Chuang J, Fitzsimons D, Tangney J, Hidalgo CG, Chung CS, Cheng H, Dalton ND, Gu Y, Kasahara H, Ghassemian M, Omens JH, Peterson KL, Granzier HL, Moss RL, McCulloch AD, Chen J. Mouse and computational models link Mlc2v dephosphorylation to altered myosin kinetics in early cardiac disease. J Clin Invest 2012;122:1209–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding P, Huang J, Battiprolu PK, Hill JA, Kamm KE, Stull JT. Cardiac myosin light chain kinase is necessary for myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation and cardiac performance in vivo. J Biol Chem 2010;285:40819–40829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan JY, Takeda M, Briggs LE, Graham ML, Lu JT, Horikoshi N, Weinberg EO, Aoki H, Sato N, Chien KR, Kasahara H. Identification of cardiac-specific myosin light chain kinase. Circ Res 2008;102:571–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mizutani H, Okamoto R, Moriki N, Konishi K, Taniguchi M, Fujita S, Dohi K, Onishi K, Suzuki N, Satoh S, Makino N, Itoh T, Hartshorne DJ, Ito M. Overexpression of myosin phosphatase reduces Ca(2+) sensitivity of contraction and impairs cardiac function. Circ J 2010;74:120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okamoto R, Kato T, Mizoguchi A, Takahashi N, Nakakuki T, Mizutani H, Isaka N, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Kaibuchi K, Lu Z, Mabuchi K, Tao T, Hartshorne DJ, Nakano T, Ito M. Characterization and function of MYPT2, a target subunit of myosin phosphatase in heart. Cell Signal 2006;18:1408–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Godin CM, Ferguson SS. The angiotensin II type 1 receptor induces membrane blebbing by coupling to Rho A, Rho kinase, and myosin light chain kinase. Mol Pharmacol 2010;77:903–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimura K, Ito M, Amano M, Chihara K, Fukata Y, Nakafuku M, Yamamori B, Feng J, Nakano T, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. Regulation of myosin phosphatase by Rho and Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase). Science 1996;273:245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]