Abstract

Infants with cardiopulmonary disorders associated with hypoxia develop pulmonary hypertension. We previously showed that initiation of oral L-citrulline before and continued throughout hypoxic exposure improves nitric oxide (NO) production and ameliorates pulmonary hypertension in newborn piglets. Rescue treatments, initiated after the onset of pulmonary hypertension, better approximate clinical strategies. Mechanisms by which L-citrulline improves NO production merit elucidation. The objective of this study was to determine whether starting L-citrulline after the onset of pulmonary hypertension inhibits disease progression and improves NO production by recoupling endothelial NO synthase (eNOS). Hypoxic and normoxic (control) piglets were studied. Some hypoxic piglets received oral L-citrulline starting on Day 3 of hypoxia and continuing throughout the remaining 7 days of hypoxic exposure. Catheters were placed for hemodynamic measurements, and pulmonary arteries were dissected to assess NO production and eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios (a measure of eNOS coupling). Pulmonary vascular resistance was lower in L-citrulline–treated hypoxic piglets than in untreated hypoxic piglets but was higher than in normoxic controls. NO production and eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios were greater in pulmonary arteries from L-citrulline–treated than from untreated hypoxic animals but were lower than in normoxic controls. When started after disease onset, oral L-citrulline treatment improves NO production by recoupling eNOS and inhibits the further development of chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension in newborn piglets. Oral L-citrulline may be a novel strategy to halt or reverse pulmonary hypertension in infants suffering from cardiopulmonary conditions associated with hypoxia.

Keywords: nitric oxide signaling, uncoupled eNOS, superoxide

Clinical Relevance

Treatment options to prevent the progressive development of pulmonary hypertension in infants with cardiopulmonary disorders associated with persistent or episodic hypoxia are largely ineffective. We previously showed that prophylactic treatment with oral L-citrulline improves nitric oxide (NO) production and ameliorates chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension in newborn piglets. The effectiveness of rescue treatment with oral L-citrulline initiated after the onset of pulmonary hypertension is not yet known. We demonstrate that oral L-citrulline is an effective rescue treatment to ameliorate chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension in newborn piglets. Recoupling endothelial nitric oxide synthase is an important mechanism by which prolonged in vivo treatment with oral L-citrulline improves NO production during exposure to chronic hypoxia.

Infants with lung and heart disease who experience persistent or episodic hypoxia can develop progressive pulmonary hypertension (1, 2). Effective treatments for infants with chronic forms of pulmonary hypertension remain inadequate (3, 4). Better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of chronic pulmonary hypertension may lead to novel therapies. There is increasing evidence that chronic forms of pulmonary hypertension, including chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension, are associated with impaired nitric oxide (NO) signaling (5–7).

Consistent with the findings of others (7, 8), we recently provided evidence that endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) uncoupling contributes to impaired NO signaling in a newborn piglet model of chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension (9). In the homodimeric or coupled state, electrons are transferred from the eNOS reductase domain to the oxygenase domain, and NO is produced (7). When eNOS becomes uncoupled, electrons are diverted to molecular oxygen–producing superoxide (O2∙−) instead of NO.

L-arginine is known to promote eNOS coupling (10, 11). Beneficial effects have been demonstrated in experimental models of pulmonary hypertension by providing L-arginine as a strategy to recouple eNOS (12, 13). However, inconsistent and detrimental effects have been reported with L-arginine therapy (14, 15).

An alternate way to increase intracellular L-arginine and to recouple eNOS is via supplementation with L-citrulline, the precursor for L-arginine. In support of this approach, we recently showed that L-citrulline increases NO production and recouples eNOS in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells from newborn piglets cultured under hypoxic conditions (16). Moreover, we found that oral treatment with L-citrulline started immediately before and continued throughout hypoxic exposure increases NO production and ameliorates the development of chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension in newborn piglets (17). However, “rescue” treatment with interventions initiated after the onset of pulmonary hypertension better approximates current clinical strategies.

We previously established that pulmonary hypertension develops when piglets are exposed to 3 days of hypoxia and worsens when hypoxic exposure is extended to 10 days (18, 19). The major purpose of this study was to determine whether a “rescue” treatment strategy (i.e., starting L-citrulline after the onset of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension) ameliorates the progression of pulmonary hypertension. We also performed studies to evaluate whether in vivo eNOS recoupling occurs with oral L-citrulline therapy in newborn piglets.

Some of the results of these studies have been reported in the form of an abstract (20).

Materials and Methods

Detailed methods are provided in the online supplement.

Animal Care and In Vivo Hypoxia Model

The use of animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University Medical Center. York-Landrace mixed-breed piglets were obtained from the vendor on Day of Life 2 and raised in either a normoxic environment or a normobaric hypoxia environment until Day of Life 11 to 12 (9–10 d of normoxia or hypoxia). Other normoxic control piglets were studied on the day of arrival from the vendor at either Day of Life 5 to 6 (for L-citrulline bioavailability studies) or Day of Life 12 (to serve as the comparable age control group for the hypoxic animals).

Animals: Bioavailability of Oral L-Citrulline

An orogastric tube was placed in normoxic control piglets, and one of three doses of L-citrulline (0.13, 0.26, or 0.5 g/kg) was administered. Blood samples were collected before and at intervals over the 8 hours after administration of L-citrulline.

Animals: Chronic L-Citrulline Supplementation

Some hypoxic piglets were given oral L-citrulline starting on the third day of hypoxic exposure and continuing for an additional 7 days of hypoxia. Piglets were treated with a lower (0.26–0.52 g/kg/d) or higher (1–1.5 g/kg/d) total daily dosing strategy. For the lower dosing, 0.13–0.26 g/kg L-citrulline was given orally by syringe twice a day. For the higher dosing, 0.26 g/kg L-citrulline was given orally by syringe twice a day, and additional L-citrulline (0.5–1.0 g/kg) was mixed in milk, which was consumed throughout the day.

Animals: In Vivo Hemodynamics

After placing catheters (17) and with all animals breathing room air, pulmonary arterial pressure, systemic blood pressure, left ventricular end diastolic pressure, and cardiac output were measured. Blood samples were drawn for determination of L-citrulline levels.

Right Ventricular Mass Assessment

The weight of the right ventricular free wall was divided by the weight of the left ventricular wall and septum.

Pulmonary Artery Isolation

Small pulmonary arteries (≤300 μm) were dissected from the lungs of all groups of piglets.

Cannulated Artery Studies

Studies were performed to determine whether small pulmonary artery responses to the endothelium-dependent dilator acetylcholine (ACh) (10−9 to 10−5 M), the NOS antagonist Nω-nitro-L-arginine methylester (l-NAME) (10−6 to 10−3 M), or the NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetyl-penicillamine (SNAP) (10−9 to 10−5 M) were altered by chronic in vivo hypoxia or by citrulline treatment during chronic in vivo hypoxia.

NO and O2∙− Measurements and Immunoblot Analysis of eNOS, Phospho-eNOS (Ser1177), and eNOS Dimers and Monomers

Small pulmonary arteries were used to assess NO production by electron spin resonance (21) or O2∙− production by electron spin resonance with 1-hydroxy-3-methoxycarbonyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-pyrrolidine as a spin probe (22) or for immunoblot analysis of eNOS, phospho-eNOS (Ser1177), and eNOS dimers/monomers.

Plasma and Vessel Amino Acid Measurements

Concentrations of citrulline and arginine were determined by amino acid analysis (17, 23).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Data were compared by unpaired t test or one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s protected least significant difference post hoc comparison test as appropriate. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant (24).

Results

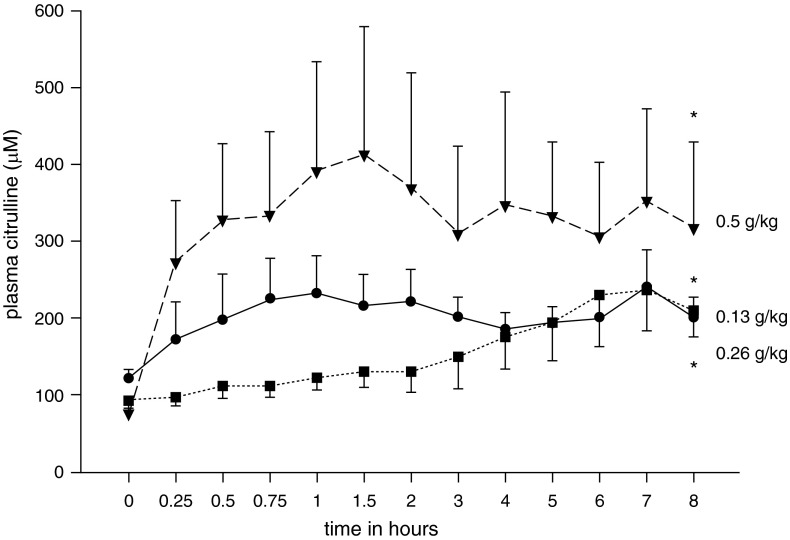

We first performed studies to determine plasma levels achieved in treatment-naive normoxic control piglets 8 hours after administration of a single oral bolus dose of L-citrulline (0.13, 0.26, or 0.5 g/kg). At 8 hours after the oral dose, the plasma L-citrulline level was 50 to 100% above baseline (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Plasma L-citrulline levels after a single oral-gastric bolus of L-citrulline in treatment-naive normoxic control piglets. Eight hours after administration of an oral-gastric dose of L-citrulline (0.13 g/kg [circles; n = 6], 0.26 g/kg [squares; n = 4], or 0.5 g/kg [inverted triangles; n = 4]), plasma L-citrulline levels were 50 to 100% above baseline. All values are mean ± SEM. *Different from time 0 baseline level (P < 0.05; unpaired t test).

After confirming oral bioavailability, we performed studies to evaluate the effect on the development of chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension from low (total daily dose of 0.26–0.52 g/kg/d) and high (total daily dose of 1.0–1.5 g/kg/d) oral L-citrulline dosing strategies given from Day 3 to Day 10 of hypoxia as boluses administered twice a day (for low dose) or as boluses administered twice a day combined with adding L-citrulline to milk feedings (for high doses). Consistent with our previous findings (17, 19), pulmonary arterial pressure and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure were greater in the untreated group of chronically hypoxic piglets than in the comparable-age, normoxic control group (Table 1). Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure measurements were reduced in the high-dose, but not the low-dose, L-citrulline–treated hypoxic animals relative to untreated hypoxic animals (Table 1). Pulmonary arterial pressures measured in low-dose and high-dose groups of L-citrulline–treated hypoxic animals were greater than those measured in the control animals but were significantly lower than pulmonary arterial pressures in untreated hypoxic animals (Table 1). Measurements of aortic pressure, arterial pH, arterial Po2, and arterial Pco2 were similar for all four groups of piglets (Table 1; see Table E1 in the online supplement). Cardiac output did not differ significantly between any of the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data for Normoxic (Control), Chronic Hypoxic, and L-Citrulline–Treated Chronic Hypoxic Piglets

| Treatment Group | Weight (kg) | Pulmonary Arterial Pressure (cm H2O) | LVEDP (cm H2O) | Cardiac Output (ml/min/kg) | Aortic Pressure (cm H2O) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (normoxic) (n = 7) | 3.4 ± 0.35* | 18.7 ± 1 | 4 ± 0.5 | 416 ± 14 | 89 ± 4 |

| Chronic hypoxic (n = 8) | 2.6 ± 0.09† | 39 ± 3† | 6.1 ± 0.6† | 345 ± 31 | 86 ± 3 |

| Low-dose citrulline treatment, chronic hypoxic (n = 6) | 2.5 ± 0.09† | 30 ± 2†‡ | 6.5 ± 0.2† | 300 ± 35 | 82 ± 6 |

| High-dose citrulline treatment, chronic hypoxic (n = 8) | 2.7 ± 0.12† | 29.8 ± 2†‡ | 5.3 ± 0.4 | 364 ± 30 | 82 ± 5 |

Definition of abbreviation: LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure.

Values are means ± SEM.

Different from normoxic controls (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test).

Different from chronic hypoxic (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test).

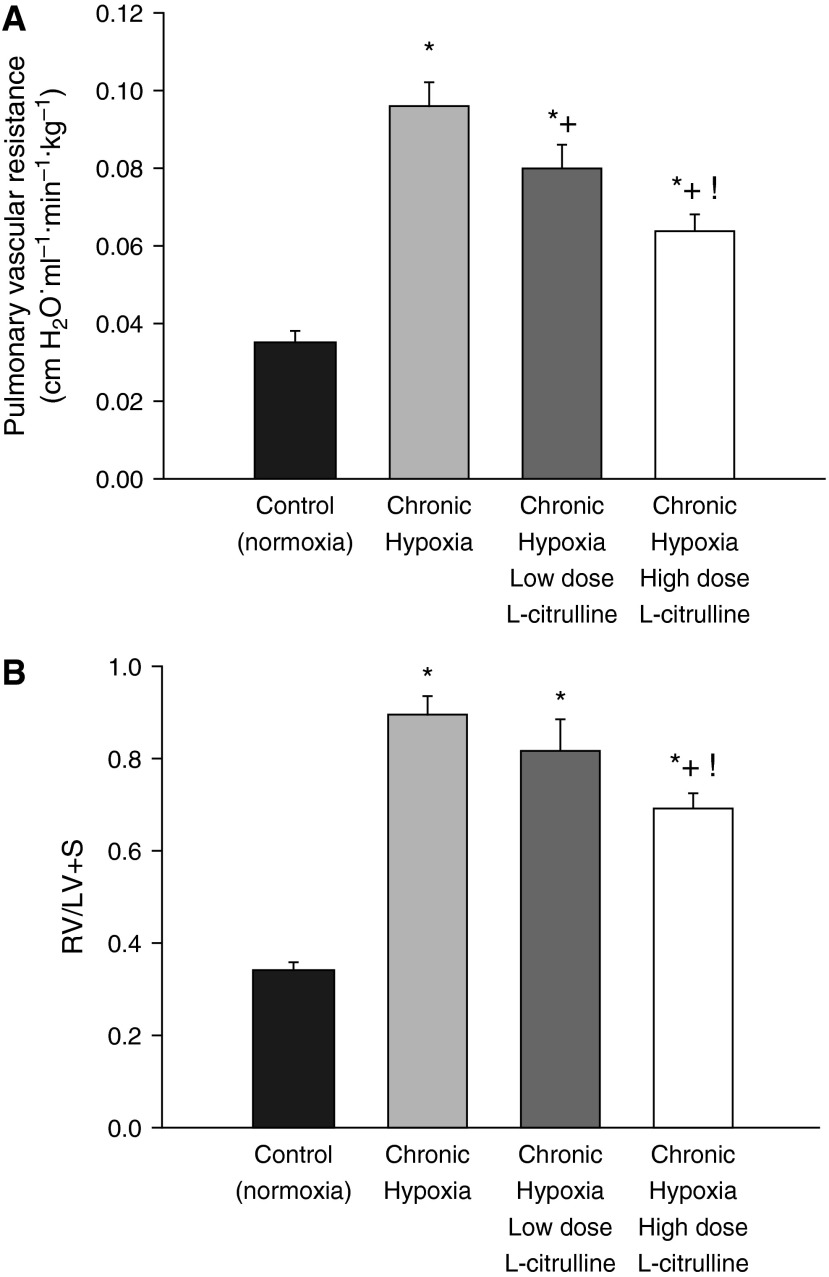

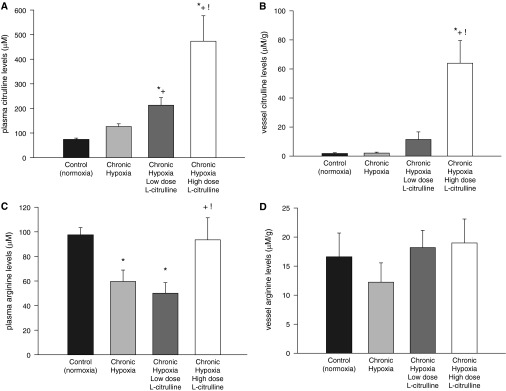

As shown in Figure 2A, low-dose and high-dose treatment with L-citrulline reduced pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) in hypoxic piglets to values less than those in untreated hypoxic piglets but higher than those in normoxic controls. Moreover, PVR was less in hypoxic piglets treated with the high versus the low L-citrulline dosage strategy (Figure 2A). The impact on right ventricular mass also differed between the high-dose and low-dose L-citrulline treatment strategies, with the high, but not the low, L-citrulline group demonstrating a reduced right ventricular mass compared with those observed in untreated hypoxic animals (Figure 2B). The differential impact of L-citrulline treatment on PVR and right ventricular mass correlated with the plasma citrulline levels that were measured on the day of study (Figure 3A). Specifically, higher plasma citrulline levels were measured in the high-dose versus the low-dose–treated animals. Moreover, citrulline levels were greater in vessels dissected from piglets who received the high L-citrulline dosage strategy than in vessels dissected from any of the other groups of piglets (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

(A) Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) in control (normoxic) and chronically hypoxic piglets. Low-dose (n = 6) and high-dose (n = 8) L-citrulline treatment reduced PVR in hypoxic piglets to values less than those in untreated (n = 8) hypoxic piglets but higher than values in normoxic controls (n = 7). PVR was less in hypoxic piglets treated with the high- versus low-dose L-citrulline. *Different from control (normoxia); +different from untreated chronic hypoxia; !different from low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test). (B) Fulton index (i.e., right ventricular free wall divided by the weight of the left ventricular wall and septum [RV/LV+S]) measurements of right ventricular mass in control (normoxic) and chronically hypoxic piglets. All three groups of chronically hypoxic piglets developed increased right heart mass compared with normoxic controls (normoxic controls, n = 12; untreated chronic hypoxia, n = 12; low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia, n = 6; high-dose L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia, n = 10). High-dose, but not low-dose, L-citrulline treatment reduced right ventricular mass in chronically hypoxic piglets to values below those measured in untreated chronically hypoxic piglets. *Different from control (normoxia); +different from untreated chronic hypoxia; !different from low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test).

Figure 3.

(A) Plasma L-citrulline levels in control (normoxic) and chronically hypoxic piglets. Plasma L-citrulline levels were greater in chronically hypoxic piglets receiving high-dose L-citrulline treatment (n = 10) than in normoxic control piglets (n = 12), in untreated chronically hypoxic piglets (n = 12), or in piglets receiving low-dose L-citrulline treatment (n = 6). *Different from control (normoxia); +different from untreated chronic hypoxia; !different from low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test). (B) L-citrulline levels in small pulmonary arteries from control (normoxic) and chronically hypoxic piglets. L-citrulline levels were greater in small pulmonary arteries from chronically hypoxic piglets receiving high-dose L-citrulline treatment (n = 10) than in small pulmonary arteries from normoxic control piglets (n = 10), untreated chronically hypoxic piglets (n = 8), or piglets receiving low-dose L-citrulline (n = 6). *Different from control (normoxia); +different from untreated chronic hypoxia; !different from low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test). (C) Plasma L-arginine levels in control (normoxic) and chronically hypoxic piglets. Plasma L-arginine levels were lower in untreated hypoxic animals (n = 12) than in normoxic control animals (n = 12). Plasma L-arginine levels were similar to control animals in piglets treated with high-dose (n = 10), but not low-dose (n = 6), L-citrulline. *Different from control (normoxia); +different from untreated chronic hypoxia; !different from low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test). (D) L-arginine levels in small pulmonary arteries from control (normoxia) and chronically hypoxic piglets. L-arginine levels were similar in small pulmonary arteries from all groups of piglets (normoxic control piglets, n = 10; untreated chronically hypoxic piglets, n = 8; low-dose L-citrulline–treated piglets, n = 6; high-dose L-citrulline–treated piglets, n = 10).

Plasma arginine levels were lower in untreated hypoxic animals than in control animals (Figure 3C). High-dose, but not low-dose, L-citrulline treatment restored plasma arginine to levels similar to control animals (Figure 3C). Tissue arginine levels were similar in vessels dissected from all groups of piglets (Figure 3D).

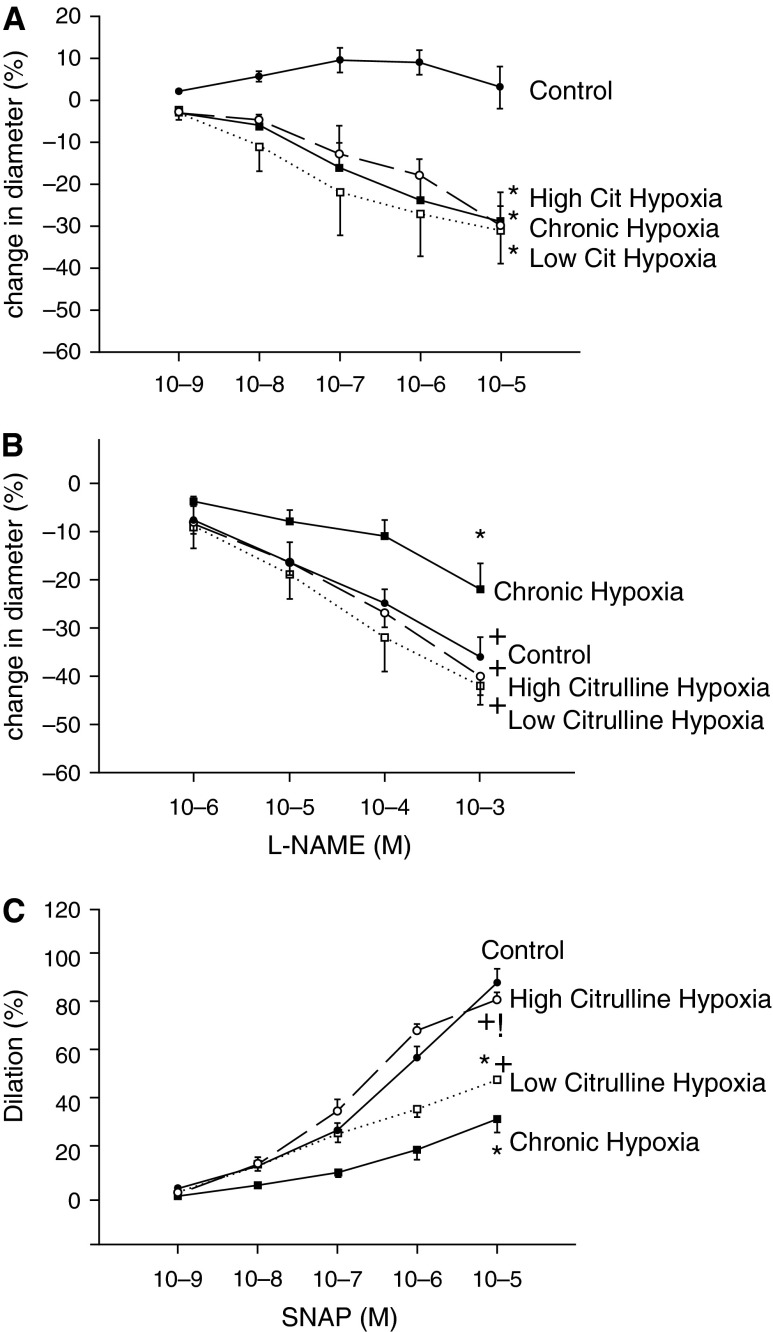

Consistent with our previous findings, functional responses to the endothelium-dependent dilator ACh, the NOS antagonist l-NAME, and the NO donor SNAP were diminished in small pulmonary arteries from the untreated group of hypoxic animals when compared with responses to these agents in pulmonary arteries from the comparable age normoxic control group (5, 9) (Figures 4A–4C). Responses to ACh did not differ between pulmonary arteries from any of the groups of hypoxic piglets (Figure 4A). Responses to l-NAME in pulmonary arteries from both groups of L-citrulline–treated hypoxic piglets were greater than those from untreated hypoxic piglets and were similar to those for pulmonary arteries from control piglets (Figure 4B). Likewise, responses to SNAP were greater for pulmonary arteries from both groups of L-citrulline–treated hypoxic piglets than for the untreated group of hypoxic piglets. However, only pulmonary arteries from the high-dose L-citrulline–treated group of piglets exhibited responses to SNAP that were similar to those in pulmonary arteries from control animals (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

(A) Responses to the endothelium-dependent vasodilator acetylcholine (ACh) in small pulmonary arteries from control (normoxic) and chronically hypoxic piglets. Small pulmonary arteries from normoxic control piglets dilated to ACh (n = 10); ACh elicited a similar degree of constriction in small pulmonary arteries from all groups of hypoxic piglets, whether untreated (n = 6) or treated with low-dose (n = 3) or high-dose (n = 4) L-citrulline (Cit). *Different from control (normoxia) (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test). (B) Responses to the nitric oxide (NO) synthase antagonist Nω-nitro-L-arginine methylester (l-NAME) in small pulmonary arteries from control (normoxic) and chronically hypoxic piglets. Responses to l-NAME were less for small pulmonary arteries from the untreated group of hypoxic piglets (n = 8) than for any other group of piglets. Small pulmonary arteries from low-dose (n = 3) and high-dose (n = 10) L-citrulline–treated groups of chronically hypoxic piglets had responses to l-NAME that were similar to normoxic control piglets (n = 12). *Different from control (normoxia); +different from untreated chronic hypoxia (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test). (C) Responses to the NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetyl-penicillamine (SNAP) in small pulmonary arteries from control (normoxic) and chronically hypoxic piglets. Responses to SNAP were less for small pulmonary arteries from the untreated group of hypoxic piglets (n = 9) than for any other group of piglets. Small pulmonary arteries from low-dose (n = 5) and high-dose (n = 9) L-citrulline–treated groups of chronically hypoxic piglets had responses to SNAP that were greater than untreated hypoxic piglets. Responses to SNAP were similar for small pulmonary arteries from normoxic control piglets (n = 10) and high-dose L-citrulline–treated chronically hypoxic piglets. *Different from control (normoxia); +different from untreated chronic hypoxia; !different from low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test).

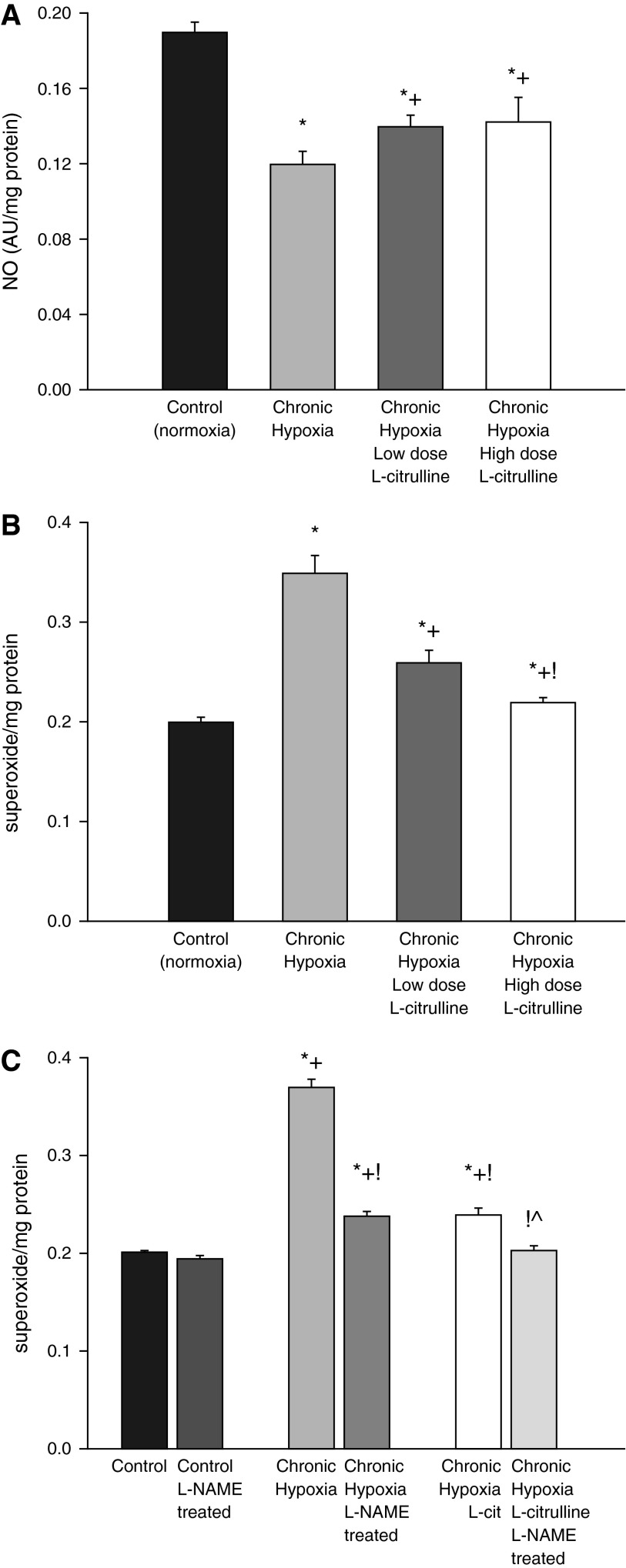

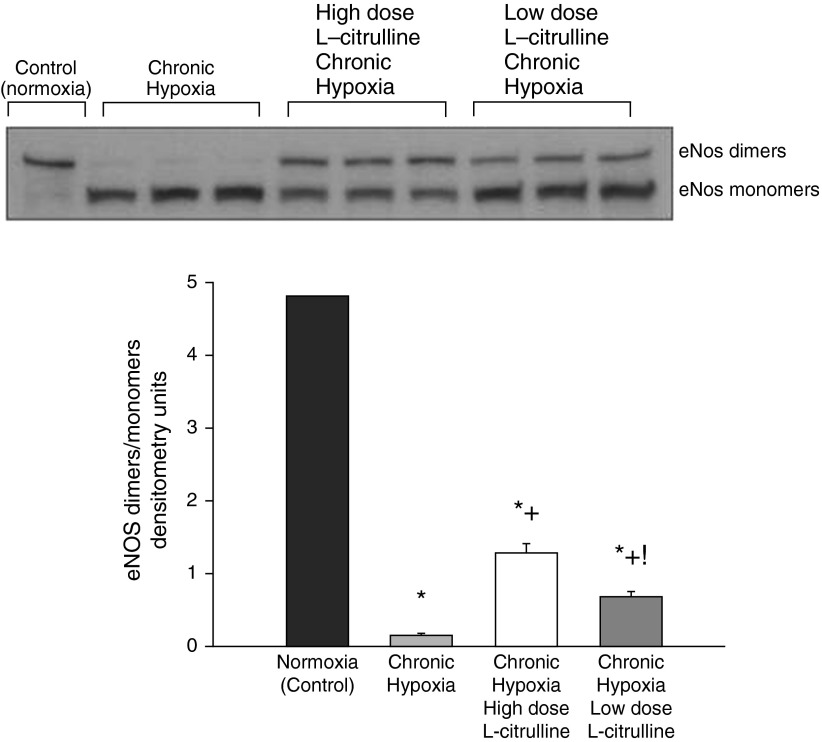

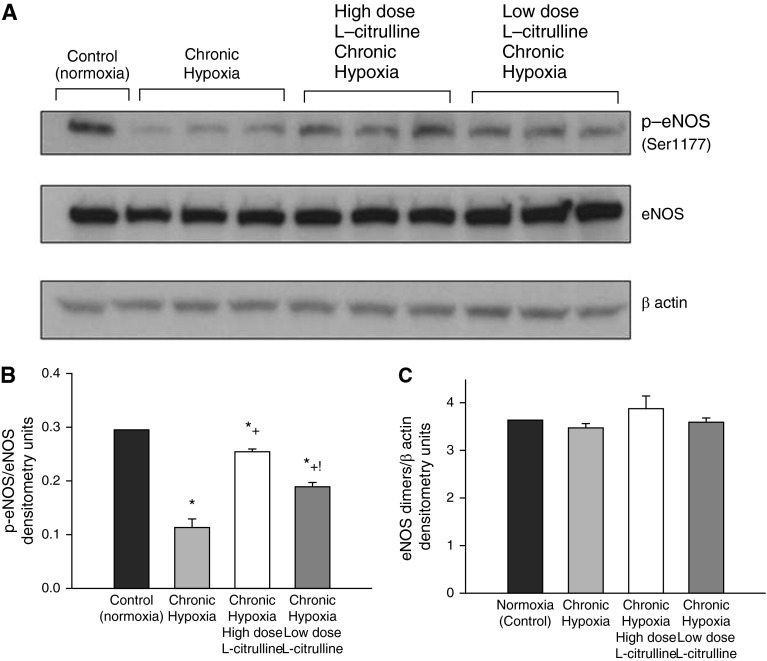

NO production was higher and O2∙− generation was lower in small pulmonary arteries from control piglets than from all groups of hypoxic piglets regardless of whether or not they received L-citrulline treatment (Figures 5A and 5B). Likewise, eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios (Figure 6) and phospho-eNOS (Ser1177) expression (Figure 7) were less in pulmonary arteries from all groups of hypoxic piglets when compared with their respective values in pulmonary arteries from normoxic control piglets. There was no difference in total eNOS expression between pulmonary arteries from any of the piglet groups (Figure 7). When compared with pulmonary arteries from the untreated group of hypoxic piglets, pulmonary arteries from both the high- and low-dose groups of L-citrulline–treated hypoxic piglets demonstrated greater NO production (Figure 5A), less O2∙− generation (Figure 5B), and higher values for eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios (Figure 6) and phospho-eNOS (Ser1177) expression (Figure 7). Ex vivo treatment with l-NAME reduced O2∙− generation in pulmonary arteries dissected from untreated and L-citrulline–treated hypoxic piglets (Figure 5C), but the impact was greater in the arteries dissected from the untreated (36 ± 1% reduction) than the L-citrulline–treated (15 ± 1% reduction) hypoxic animals. Moreover, O2∙− generation was less (Figure 5B), and eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios (Figure 6) and phospho-eNOS (Ser1177) expression (Figure 7) were greater, with high-dose than with low-dose L-citrulline treatment.

Figure 5.

(A) NO production by small pulmonary arteries from control (normoxic) and chronically hypoxic piglets. NO production was greater for small pulmonary arteries from normoxic control piglets (n = 6) than from all groups of hypoxic piglets. Small pulmonary arteries from low-dose (n = 5) and high-dose (n = 10) L-citrulline–treated groups of piglets had greater NO production than untreated (n = 5) hypoxic animals. *Different from control (normoxia); +different from untreated chronic hypoxia (ANOVA with post hoc comparison test). (B) Superoxide (O2∙−) production by small pulmonary arteries from control (normoxic) and chronically hypoxic piglets. O2∙− production was less for small pulmonary arteries from normoxic control piglets (n = 6) than from all groups of hypoxic piglets. Small pulmonary arteries from low-dose (n = 5) and high-dose (n = 10) L-citrulline–treated groups of piglets had less O2∙− production than untreated (n = 6) hypoxic animals. O2∙− production was less for pulmonary arteries from high-dose compared with low-dose–treated chronically hypoxic piglets. *Different from control (normoxia); +different from untreated chronic hypoxia; !different from low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test). (C) Effect of l-NAME treatment on O2∙− production by small pulmonary arteries from control (normoxic) and chronically hypoxic piglets. O2∙− production was unchanged by ex vivo l-NAME (10−4 M) treatment in small pulmonary arteries from control (normoxic) piglets (n = 5). Ex vivo treatment with l-NAME reduced O2∙− generation in small pulmonary arteries from untreated (n = 5) and L-citrulline–treated (n = 5) groups of hypoxic piglets. *Different from control (normoxia); +different from ex vivo l-NAME–treated control (normoxia); !different from chronic hypoxia; ^different from L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test).

Figure 6.

A representative Western blot for endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) dimer-to-monomer ratios with corresponding densitometry shows that small pulmonary arteries from low- and high-dose L-citrulline–treated groups of piglets had greater eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios than untreated hypoxic animals. eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios were greater for pulmonary arteries from high-dose compared with low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronically hypoxic piglets. *Different from control (normoxia); +different from untreated chronic hypoxia; !different from low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test).

Figure 7.

Representative Western blot for phospho-eNOS (Ser1177) (p-eNOS), eNOS, and β-actin (A) and corresponding densitometry (B and C) show that small pulmonary arteries from low-dose and high-dose L-citrulline–treated groups of piglets had greater p-eNOS/eNOS ratios than untreated hypoxic animals. The p-eNOS/eNOS ratios were greater in pulmonary arteries from high-dose compared with low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronically hypoxic piglets. eNOS/β actin expression was similar in small pulmonary arteries from all groups of piglets. *Different from control (normoxia); +different from untreated chronic hypoxia; !different from low-dose L-citrulline–treated chronic hypoxia (P < 0.05; ANOVA with post hoc comparison test).

Discussion

Our studies in piglets with chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension reveal a number of novel effects of oral L-citrulline treatment. We provide new evidence that oral L-citrulline increases NO production in the pulmonary circulation of hypoxic piglets by recoupling eNOS in vivo. Moreover, prolonged treatment with L-citrulline improves pulmonary vascular responses to NO-dependent agents. We show for the first time that, when used as a “rescue” strategy, L-citrulline ameliorates the development of chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension in newborn piglets.

These findings and our previous studies (5, 9, 16, 19) are consistent with the accumulating body of evidence in humans and in animal models that impaired NO signaling is involved in the pathogenesis of chronic pulmonary hypertension (6, 25, 26). Our findings provide support that uncoupled eNOS contributes to impaired NO signaling in the pulmonary circulation of newborn animals with chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension (9, 16). L-arginine, which is known to promote eNOS coupling, has been studied in humans and in animal models as a therapy to improve NO signaling, restore pulmonary vascular dysfunction, and ameliorate pulmonary hypertension (12, 13, 27–29). There is evidence that in vivo L-arginine treatment recouples eNOS in the monocrotaline-induced model of pulmonary hypertension in rats (13).

Pulmonary arterial endothelial cells express the enzymes needed to produce L-arginine from L-citrulline (30). L-citrulline supplementation thereby may provide a novel therapeutic strategy for increasing L-arginine bioavailability and improving NO signaling in the pulmonary circulation. There are limited data regarding the impact of in vivo L-citrulline treatment on pulmonary vascular function and pulmonary hypertension in humans or animals. When started 4 days after the onset of exposure to hyperoxia, subcutaneous treatment with L-citrulline was shown to inhibit the development of pulmonary hypertension in a newborn rat model of hyperoxia-induced bronchopulmonary dysplasia (31). This study did not evaluate the impact of L-citrulline treatment on pulmonary vascular NO production or on NO signaling impairments.

Postoperative pulmonary hypertension was not observed in children undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass who achieved plasma levels greater than 37 μM after treatment with oral L-citrulline or who had naturally elevated levels of L-citrulline (32). Intravenous L-citrulline administered to a similar patient population was found to be safe and well tolerated, although evaluation for efficacy is ongoing (33).

We have previously shown that oral L-citrulline treatment started before and continued throughout hypoxic exposure increased pulmonary vascular NO production and prevented the development of chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension in newborn piglets (17). We now show that when started after exposure to 3 days of hypoxia, a time period known to induce pulmonary hypertension, oral L-citrulline treatment inhibits the further development of pulmonary hypertension. These new findings are clinically relevant because rescue treatment strategies started after the onset of pulmonary hypertension rather than prophylactically align with clinical practice. Mechanistically, our new data show that L-citrulline treatment reduces pulmonary vascular O2∙− generation and increases eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios in small pulmonary arteries, the vessels most relevant to regulation of pulmonary vascular resistance. These findings indicate that recoupling of eNOS underlies the improved pulmonary vascular NO production found in the L-citrulline–treated groups of chronically hypoxic piglets. Consistent with our previous findings (17), eNOS expression is not altered in the pulmonary vasculature of the L-citrulline–treated piglets. Thus, our findings indicate that alterations in eNOS function, not expression, underlie improved NO signaling after L-citrulline treatment.

Also consistent with our previous findings (17), improved NO signaling was found in L-citrulline–treated piglets without concomitant increases in plasma or vessel L-arginine levels. This is not surprising because there is evidence that the enzymes needed to synthesize L-arginine from L-citrulline are colocalized with eNOS in plasmalemmal caveolae of endothelial cells (34). Thus, rather than equilibrating with bulk intracellular levels, L-citrulline–induced increases in L-arginine may be directly channeled to eNOS.

We provide other new data showing a positive impact from L-citrulline treatment on NO signaling in the pulmonary vasculature. Consistent with enhanced basal NO production, eNOS phosphorylation (Ser1177) and the functional responses to the NOS antagonist l-NAME were greater in small pulmonary arteries from L-citrulline–treated than untreated chronically hypoxic piglets. Small pulmonary arterial responses to the endothelium-dependent vasodilator ACh were not improved in L-citrulline–treated hypoxic piglets. This could be due to the inability of L-citrulline treatment to alter or override the contribution from prostanoid constrictors to ACh responses in hypoxic pulmonary arteries (5, 35). Notably, small pulmonary arteries from L-citrulline–treated hypoxic piglets exhibited improved functional responses to the NO donor SNAP. One explanation for the poor responsiveness to exogenous NO is reduced NO bioavailability caused by interactions between reactive oxygen species and NO (36). Other investigators and our laboratory have provided evidence that strategies to remove or limit the production of reactive oxygen species improve pulmonary vascular responses to exogenous NO in animals with pulmonary hypertension (9, 37, 38). Thus, the mechanism for enhanced NO responsiveness to an NO donor in vessels from L-citrulline–treated piglets is likely due, at least in part, to attenuating the amount of NO inactivated by O2∙−, thereby increasing the bioavailability of exogenous NO to activate the downstream signaling target, soluble guanylate cyclase. Our findings in pulmonary arteries treated ex vivo with l-NAME indicate that this O2∙− is derived, at least in part, from uncoupled eNOS. These findings have important potential therapeutic implications. It is well known that infants with chronic progressive pulmonary hypertension have poor and erratic pulmonary dilator responses to inhaled NO therapy (39, 40). The possibility that L-citrulline treatment could improve responses to inhaled NO in vivo merits further investigation.

We also found that the degree of increase in right ventricular mass was improved in chronically hypoxic piglets treated with the higher dose of L-citrulline. The failure of the lower dose of L-citrulline to reduce the elevation in right ventricular mass despite lowering pulmonary arterial pressure is not entirely surprising. Although right ventricular mass is a metric of pulmonary hypertension, there is increasing awareness that factors other than pressure overload contribute to right ventricular modeling, especially in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (41, 42).

The potential advantages of prolonged oral treatment with L-citrulline rather than L-arginine merit comment. Oral L-arginine bioavailability is poor due to large presystemic and systemic catabolic losses from arginase present in intestinal epithelial cells and hepatocytes, which hydrolyzes arginine to ornithine and urea (43, 44). In contrast, L-citrulline, which is arginase resistant and endogenously produced by enterocytes and hepatocytes (45, 46), has been shown to have high oral bioavailability in adult humans (47, 48). Our findings in newborn piglets confirm the bioavailability of oral L-citrulline. Another consideration is that long-term treatment with oral L-arginine has been associated with adverse outcomes in adult humans with systemic vascular diseases (15, 49). Although not yet studied for the long-term treatment of pulmonary hypertension or other vascular diseases, prolonged use of oral L-citrulline holds promise for a safe therapeutic approach because children with some metabolic diseases receive oral L-citrulline for decades and show no evidence of toxicity from its use (50).

In summary, oral L-citrulline given in a “rescue” treatment strategy improves NO production and reduces O2∙- generation in the pulmonary circulation of piglets with chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension via a mechanism involving recoupling eNOS. These beneficial effects from L-citrulline are associated with improved responses to exogenous NO in small pulmonary arteries ex vivo and with the amelioration of chronic hypoxia–induced pulmonary hypertension in newborn piglets in vivo. These findings with an oral, readily bioavailable therapy are of particular interest for infants requiring prolonged treatment for effective inhibition or resolution of chronic pulmonary hypertension. Intravenous and inhaled therapies are difficult to maintain in infants and young children and are fraught with complications when used long term. Our findings in a newborn animal model should serve as the impetus to perform clinical trials of the safety and efficacy of prolonged oral L-citrulline therapy in human infants with chronic forms of pulmonary hypertension, particularly in infants suffering from conditions associated with chronic or intermittent hypoxia.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1HL097566 (C.D.F.).

Author Contributions: C.D.F.: Hypothesis generation, study design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and article writing. A.D.: Study design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and article writing. M.R.K.: Data acquisition and analysis. G.C.: Data analysis. M.S.: Hypothesis generation, study design, data analysis, and interpretation. J.L.A.: Hypothesis generation, study design, data analysis and interpretation, and article writing.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0351OC on December 23, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Mourani PM, Abman SH. Pulmonary vascular disease in bronchopulmonary dysplasia: pulmonary hypertension and beyond. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25:329–337. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328360a3f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stenmark KR, Abman SH. Lung vascular development: implications for the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:623–661. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.102229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abman SH. Monitoring cardiovascular function in infants with chronic lung disease of prematurity. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;87:F15–F18. doi: 10.1136/fn.87.1.F15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khemani E, McElhinney DB, Rhein L, Andrade O, Lacro RV, Thomas KC, Mullen MP. Pulmonary artery hypertension in formerly premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: clinical features and outcomes in the surfactant era. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1260–1269. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fike CD, Aschner JL, Zhang Y, Kaplowitz MR. Impaired NO signaling in small pulmonary arteries of chronically hypoxic newborn piglets. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L1244–L1254. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00345.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klinger JR, Abman SH, Gladwin MT. Nitric oxide deficiency and endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:639–646. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0686PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabima DM, Frizzell S, Gladwin MT. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in pulmonary hypertension. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1970–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kietadisorn R, Juni RP, Moens AL. Tackling endothelial dysfunction by modulating NOS uncoupling: new insights into its pathogenesis and therapeutic possibilities. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E481–E495. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00540.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fike CD, Dikalova A, Slaughter JC, Kaplowitz MR, Zhang Y, Aschner JL. Reactive oxygen species-reducing strategies improve pulmonary arterial responses to nitric oxide in piglets with chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:1727–1738. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gielis JF, Lin JY, Wingler K, Van Schil PE, Schmidt HH, Moens AL. Pathogenetic role of eNOS uncoupling in cardiopulmonary disorders. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:765–776. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martásek P, Miller RT, Liu Q, Roman LJ, Salerno JC, Migita CT, Raman CS, Gross SS, Ikeda-Saito M, Masters BSS. The C331A mutant of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase is defective in arginine binding. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34799–34805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.34799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitani Y, Maruyama K, Sakurai M. Prolonged administration of L-arginine ameliorates chronic pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling in rats. Circulation. 1997;96:689–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ou Z-J, Wei W, Huang DD, Luo W, Luo D, Wang ZP, Zhang X, Ou JS. L-arginine restores endothelial nitric oxide synthase-coupled activity and attenuates monocrotaline-induced pulmonary artery hypertension in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E1131–E1139. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00107.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Böger RH. L-arginine therapy in cardiovascular pathologies: beneficial or dangerous? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:55–61. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f2b0c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulman SP, Becker LC, Kass DA, Champion HC, Terrin ML, Forman S, Ernst KV, Kelemen MD, Townsend SN, Capriotti A, et al. L-arginine therapy in acute myocardial infarction: the Vascular Interaction With Age in Myocardial Infarction (VINTAGE MI) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006;295:58–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dikalova A, Fagiana A, Aschner JL, Aschner M, Summar M, Fike CD. Sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter 1 (SNAT1) modulates L-citrulline transport and nitric oxide (NO) signaling in piglet pulmonary arterial endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ananthakrishnan M, Barr FE, Summar ML, Smith HA, Kaplowitz M, Cunningham G, Magarik J, Zhang Y, Fike CD. L-citrulline ameliorates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in newborn piglets. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L506–L511. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00017.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fike CD, Kaplowitz MR. Effect of chronic hypoxia on pulmonary vascular pressures in isolated lungs of newborn pigs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1994;77:2853–2862. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.6.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fike CD, Kaplowitz MR. Chronic hypoxia alters nitric oxide-dependent pulmonary vascular responses in lungs of newborn pigs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1996;81:2078–2087. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.5.2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fike CD, Dikalova A, Kaplowitz M, Summar M, Aschner J.L-citrulline recouples eNOS and ameliorates progressive chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in newborn pigs EPAS 2014. 4535.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dikalova AE, Bikineyeva AT, Budzyn K, Nazarewicz RR, McCann L, Lewis W, Harrison DG, Dikalov SI. Therapeutic targeting of mitochondrial superoxide in hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;107:106–116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.214601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dikalova A, Clempus R, Lassègue B, Cheng G, McCoy J, Dikalov S, San Martin A, Lyle A, Weber DS, Weiss D, et al. Nox1 overexpression potentiates angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy in transgenic mice. Circulation. 2005;112:2668–2676. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.538934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fike CD, Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz M, Aschner M, Summar M, Prince LS, Cunningham G, Kaplowitz M, Zhang Y, Aschner JL. Prolonged hypoxia augments L-citrulline transport by system A in the newborn piglet pulmonary circulation. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:375–384. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier U. A note on the power of Fisher’s least significant difference procedure. Pharm Stat. 2006;5:253–263. doi: 10.1002/pst.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes PJ, Dweik RA, Gelb AF, Gibson PG, George SC, Grasemann H, Pavord ID, Ratjen F, Silkoff PE, Taylor DR, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide in pulmonary diseases: a comprehensive review. Chest. 2010;138:682–692. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tonelli AR, Haserodt S, Aytekin M, Dweik RA. Nitric oxide deficiency in pulmonary hypertension: Pathobiology and implications for therapy. Pulm Circ. 2013;3:20–30. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.109911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Böger RH, Mügge A, Bode-Böger SM, Heinzel D, Höper MM, Frölich JC. Differential systemic and pulmonary hemodynamic effects of L-arginine in patients with coronary artery disease or primary pulmonary hypertension. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;34:323–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drexler H, Zeiher AM, Meinzer K, Just H. Correction of endothelial dysfunction in coronary microcirculation of hypercholesterolaemic patients by L-arginine. Lancet. 1991;338:1546–1550. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulze-Neick I, Penny DJ, Rigby ML, Morgan C, Kelleher A. Collins P, Li J, Bush A, Shinebourne EA, Redington AN. L-arginine and substance P reverse the endothelial dysfunction caused by congenital heart surgery. Circulation. 1999;100:749–755. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.7.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neill MA, Aschner J, Barr F, Summar ML. Quantitative RT-PCR comparison of the urea and nitric oxide cycle gene transcripts in adult human tissues. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;97:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vadivel A, Aschner JL, Rey-Parra GJ, Magarik J, Zeng H, Summar M, Eaton F, Thébaud B. L-citrulline attenuates arrested alveolar growth and pulmonary hypertension in oxygen-induced lung injury in newborn rats. Pediatr Res. 2010;68:519–525. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181f90278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith HAB, Canter JA, Christian KG, Drinkwater DC, Scholl FG, Christman BW, Rice GD, Barr FE, Summar ML. Nitric oxide precursors and congenital heart surgery: a randomized controlled trial of oral citrulline. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barr FE, Tirona RG, Taylor MB, Rice G, Arnold J, Cunningham G, Smith HAB, Campbell A, Canter JA, Christian KG, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of intravenously administered citrulline in children undergoing congenital heart surgery: potential therapy for postoperative pulmonary hypertension. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flam BR, Hartmann PJ, Harrell-Booth M, Solomonson LP, Eichler DC. Caveolar localization of arginine regeneration enzymes, argininosuccinate synthase, and lyase, with endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5:187–197. doi: 10.1006/niox.2001.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fike CD, Pfister SL, Kaplowitz MR, Madden JA. Cyclooxygenase contracting factors and altered pulmonary vascular responses in chronically hypoxic newborn pigs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2002;92:67–74. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2002.92.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gryglewski RJ, Palmer RMJ, Moncada S. Superoxide anion is involved in the breakdown of endothelium-derived vascular relaxing factor. Nature. 1986;320:454–456. doi: 10.1038/320454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konduri GG, Bakhutashvili I, Eis A, Pritchard K., Jr Oxidant stress from uncoupled nitric oxide synthase impairs vasodilation in fetal lambs with persistent pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1812–H1820. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00425.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinhorn RH, Albert G, Swartz DD, Russell JA, Levine CR, Davis JM. Recombinant human superoxide dismutase enhances the effect of inhaled nitric oxide in persistent pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:834–839. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banks BA, Seri I, Ischiropoulos H, Merrill J, Rychik J, Ballard RA. Changes in oxygenation with inhaled nitric oxide in severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics. 1999;103:610–618. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lönnqvist PA, Jonsson B, Winberg P, Frostell CG. Inhaled nitric oxide in infants with developing or established chronic lung disease. Acta Paediatr. 1995;84:1188–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ball MK, Waypa GB, Mungai PT, Nielsen JM, Czech L, Dudley VJ, Beussink L, Dettman RW, Berkelhamer SK, Steinhorn RH, et al. Regulation of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension by vascular smooth muscle hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:314–324. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0302OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bogaard HJ, Natarajan R, Henderson SC, Long CS, Kraskauskas D, Smithson L, Ockaili R, McCord JM, Voelkel NF. Chronic pulmonary artery pressure elevation is insufficient to explain right heart failure. Circulation. 2009;120:1951–1960. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.883843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castillo L, Chapman TE, Yu YM, Ajami A, Burke JF, Young VR. Dietary arginine uptake by the splanchnic region in adult humans. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:E532–E539. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.265.4.E532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu G. Intestinal mucosal amino acid catabolism. J Nutr. 1998;128:1249–1252. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.8.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Curis E, Nicolis I, Moinard C, Osowska S, Zerrouk N, Bénazeth S, Cynober L. Almost all about citrulline in mammals. Amino Acids. 2005;29:177–205. doi: 10.1007/s00726-005-0235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morris SM., Jr Regulation of enzymes of the urea cycle and arginine metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:87–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.110801.140547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rougé C, Des Robert C, Robins A, Le Bacquer O, Volteau C, De La Cochetière MF, Darmaun D. Manipulation of citrulline availability in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G1061–G1067. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00289.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwedhelm E, Maas R, Freese R, Jung D, Lukacs Z, Jambrecina A, Spickler W, Schulze F, Böger RH. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of oral L-citrulline and L-arginine: impact on nitric oxide metabolism. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:51–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson AM, Harada R, Nair N, Balasubramanian N, Cooke JP. L-arginine supplementation in peripheral arterial disease: no benefit and possible harm. Circulation. 2007;116:188–195. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tuchman M, Lee B, Lichter-Konecki U, Summar ML, Yudkoff M, Cederbaum SD, Kerr DS, Diaz GA, Seashore MR, Lee H-S, et al. Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network. Cross-sectional multicenter study of patients with urea cycle disorders in the United States. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]