Summary

Bmi1, a Polycomb repressive complex member, is required for the initiation of pancreatic cancer, independently of its known ability to repress the p16 and p19 tumor suppressor genes. Additionally, we show that Bmi1 regulates reactive oxygen species accumulation in pancreatic cancer cells.

Abstract

Epigenetic dysregulation is involved in the initiation and progression of many epithelial cancers. BMI1, a component of the polycomb protein family, plays a key role in these processes by controlling the histone ubiquitination and long-term repression of multiple genomic loci. BMI1 has previously been implicated in pancreatic homeostasis and the function of pancreatic cancer stem cells. However, no work has yet addressed its role in the early stages of pancreatic cancer development. Here, we show that BMI1 is required for the initiation of murine pancreatic neoplasia using a novel conditional knockout of Bmi1 in combination with a KrasG12D-driven pancreatic cancer mouse model. We also demonstrate that the requirement for Bmi1 in pancreatic carcinogenesis is independent of the Ink4a/Arf locus and at least partially mediated by dysregulation of reactive oxygen species. Our data provide new evidence of the importance of this epigenetic regulator in the genesis of pancreatic cancer.

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is one of the most lethal malignancies, with a 5 year survival rate of 6%. The National Cancer Institute estimated that 45220 patients would be diagnosed with the disease in 2013 in the USA and 38460 would die from it (SEER database). Although systemic chemotherapeutic options exist, these have limited efficacy in pancreatic cancer. The development of high-fidelity genetically engineered mouse models of PDA that recapitulate the developmental and pathologic characteristics of the human disease has led to remarkable insights into the biology of pancreatic cancer over the last decade (1–4). Complementary systems biology and genomic approaches using human samples have begun to shed some light on the mutational complement of human PDA and the pathways potentially involved in pancreatic tumorigenesis (5). Together with genetic mutations, epigenetic dysregulation has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of multiple hematopoietic and epithelial cancers (6). However, less is known about the contribution of epigenetic regulators such as the polycomb repressive complexes (PRCs) in pancreatic cancer initiation and progression.

B-cell-specific Moloney murine leukemia virus insertion site 1 (BMI1) belongs to the polycomb group of proteins that comprise the polycomb repressive complex 1 (7) and was originally identified as a cooperating oncogene with c-Myc in the E(μ)-myc transgenic mouse model of B-cell lymphoma (8). Bmi1 regulates murine embryonic fibroblast proliferation and senescence by suppressing the expression of the tumor suppressor genes p16 Ink4a and p19 Arf, which are both encoded by the Ink4a/ARF locus (9). Bmi1 −/− mice have severe neurologic and hematopoietic developmental defects (10), which are at least partially reversed when the BMI1-deficient mice are bred onto an Ink4a/Arf null background (9). Derepression of p16 Ink4a and p19 Arf each individually contributes to the phenotypes observed in Bmi1-deficient mice (11,12). More recently, BMI1 has been implicated in the regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation. Deletion of Bmi1 induces the upregulation of several genes involved in redox homeostasis leading to increased ROS generation, DNA oxidative damage and activation of the DNA damage response (DDR) pathways (13). Deletion of Chk2, a mediator of the DDR, in BMI1-deficient mice leads to increased thymocyte survival and differentiation, improved hematopoietic progenitor function, partial rescue of cerebellar development and overall increased survival (13). Notably, all of these effects appear to be independent of the upregulation of Ink4a/Arf.

BMI1 plays a key role in pancreatic biology through the regulation of both pancreatic β-cell proliferation and acinar regeneration following injury. Bmi1 −/− mice demonstrate impaired glucose tolerance and decreased β-cell mass due to the increased expression of the Ink4a/Arf locus (14). In addition, Bmi1-expressing cells are found in murine pancreatic islets and acini, where BMI1 is required for proper regeneration after pancreatitis or toxin-mediated cellular ablation (14–16). Importantly, BMI1 is highly expressed in human and murine PDA compared with normal pancreatic tissues (17–20) and its overexpression in tumors correlates with poorer prognosis in pancreatic cancer patients (19). Recent work has also implicated Bmi1 in the maintenance of the cancer stem cell compartment in human PDA (18). Despite these results, it is still unknown if BMI1 plays a role in the initiation of pancreatic cancer.

Here, we utilize the Pdx1-Cre;Kras LSL-G12D (KC) murine model of pancreatic cancer (3) in combination with pancreas-specific inactivation of Bmi1 (Bmi1 fl/fl) to generate Pdx1-Cre;Kras LSL-G12D/+ ; Bmi1 fl/fl (KC;Bmi1fl/fl) mice. We demonstrate that BMI1 is required for murine pancreatic cancer initiation. This process is Ink4a/Arf-independent, as the lack of carcinogenesis is not rescued in KC;Bmi1 fl/fl ;Ink4a −/− mice, which lack the Ink4a/Arf locus. We also show that inhibition of Bmi1 in primary mouse pancreatic cancer cells leads to the upregulation of ROS. Our data suggest that BMI1 regulates the protection from excess ROS in pancreatic cells undergoing neoplastic transformation, which is required for their survival and subsequent pancreatic neoplasia development (21).

Materials and methods

Mice

Mice were housed in the specific pathogen-free facilities of the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center. This study was approved by the University of Michigan University Committee on Use and Care of Animals. The Pdx1-Cre, p48-Cre, KrasLSL-G12D, Trp53R172H/+, Ink4a−/−, R26lacZ and Bmi1CreER/+ strains have been described previously (3,4,16,22). Bmi1fl/fl mice were developed in the Morrison lab at the University of Michigan (23). All mice were genotyped by PCR analysis. Caerulein and tamoxifen were administered as described previously (16,24). Caerulein was intraperitoneally injected at a dose of 75 μg/kg hourly for 8h, 2 days in a row, for a total of 16 injections. Tamoxifen was administered by intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 9mg per 40g body wt, in 3–6 week-old mice.

β-Galactosidase staining

We stained cryosections of mouse pancreas or intestine for β-galactosidase activity as described previously (24).

Immunohistochemistry

Histology, namely hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were performed as described previously (24). Images were acquired with an Olympus BX-51 microscope, Olympus DP71 digital camera and DP Controller software. For histopathological analysis, a minimum of 50 acinar or ductal clusters were scored from at least 3 independent animals per experimental condition. Five non-overlapping, high-power images were selected from each slide and each cluster was classified based on the classification consensus (25). A list of antibodies used is included in Supplementary Table 1 available at Carcinogenesis Online.

Western blotting

Western blots were performed as described previously (24). Antibodies used for western blotting are described in Supplementary Table 1 available at Carcinogenesis Online.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA extraction, complementary DNA preparation and quantitative PCR (qPCR) were performed as described previously (24). RNA was isolated using RNeasy protect (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription reactions were conducted using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative PCR was performed using 1× SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The primer sequences used were: Bmi1 F-5′ ATGGCCGCTTGGCTCGCATT 3′, R-5′ GATAAAAGATCCCGGAAAGAGCGGC 3′; Ezh2-5′ CCCTTCCATGCAACACCCAACACA 3′, R-5′ ACGCTCAGCAGTAAGAG CAGCA 3′; p16 F-5′ TTTCGCCCAACGCCCCGAAC 3′, R-5′ CACCGGGCGGGAG AAGGTAGT 3′; p19 F-5′ CACCGGAATCCTGGACCAG 3′, R-5′ GCAGTTCGAAT CTGCACCGT 3′; Chk2 F-5′ TGACAGTGCTTCCTGTTCACA 3′, R-5′ GAGCTGGACG AACCCTGATA 3′; Nrf2 F-5′ CTCGCTGGAAAAAGAAGTG 3′, R-5′ CCGTCCAGGAG TTCAGAGG 3′; ATM F-5′ GATCTGCTCATTTGCTGCCG 3′, R-5′ GTGTGGTGGC TGATACATTTGAT 3′; BRCA1 F-5′ CGAATCTGAGTCCCCTAAAGAGC 3′, R-5′ AA GCAACTTGACCTTGGGGTAC 3′. Gapdh or cyclophilin was used as the housekeeping gene expression control. These sequences were: Gapdh F-5′ TTG ATGGCAACAATCTCCAC 3′, R-5′ CGTCCCGTAGACAAAATGGT 3′ and Cyclophilin F-5′ TCACAGAATTATTCCAGGATTCATG 3′, R-5′ TGCCGCCA GTGCCATT 3′.

Transfection and ROS levels

KC;Ink4a−/− cells (line 35) were generated in the Bardeesy lab from a KC;Ink4a−/− (as confirmed by PCR) mouse tumor. KPC cells (line 8041) were isolated in the Pasca di Magliano lab from a p48Cre;LSLKrasG12D;p53R172H (as confirmed by PCR) mouse tumor in 2012. For authentication in Fall 2014, genotyping was performed via PCR on DNA isolated from cells growing in culture to confirm Cre transgene expression in both cell lines (Supplementary Figure 1 is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Control- or Bmi1-knockdown small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were purchased from Dharmacon. Cells were subjected to siRNA treatment for 48h. H2O2 was added directly to the media at a concentration of 500 μM for 2h for ROS analysis. ROS levels were measured using the CellROX Green reagent (Life Technologies). After exposure to CellROX Green, five high-power, non-overlapping images were taken from each slide. Fluorescence levels were then measured and each group was normalized to the level of the cells without H2O2 exposed to scrambled control siRNA.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Cells were transfected using a siRNA targeting Bmi1 or control siRNA, 72h post-transfection cells were fixed using formaldehyde, lysed and processed for chromatin immunoprecipitation. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was preformed as described previously (26).

Results

BMI1+ cells in the mouse pancreas can serve as the cell of origin for pancreatic cancer

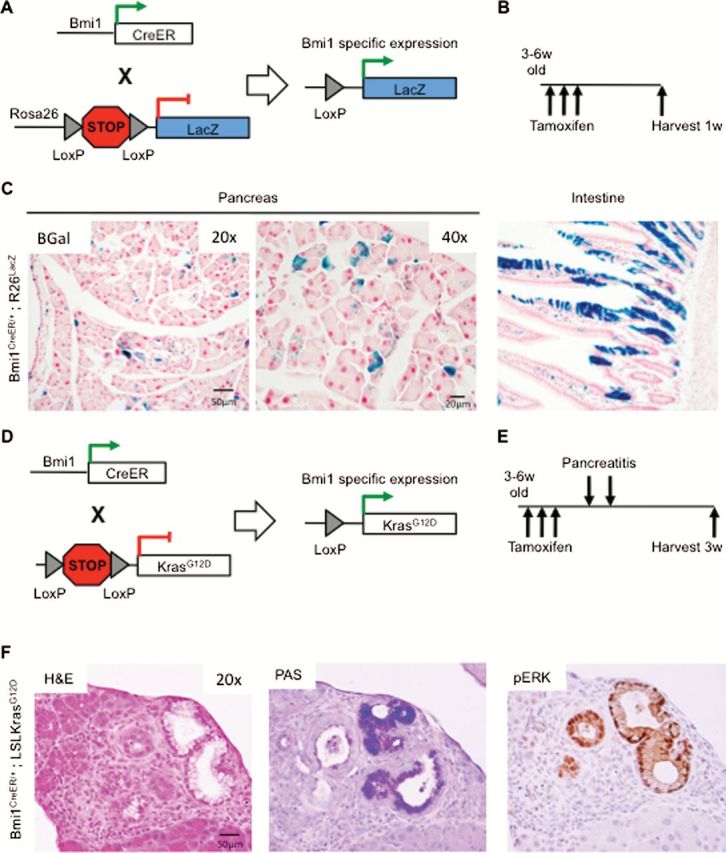

Our first goal was to determine whether BMI1-expressing cells within the mouse pancreas could give rise to PanIN lesions. Initially, we set out to identify BMI1 expression in normal pancreatic tissue. For this purpose, we crossed Bmi1-IRES-CreER mice, which express a tamoxifen-inducible Cre knocked in to the Bmi1 locus (27), with Rosa26 lacZ mice, expressing β-galactosidase from the ubiquitous Rosa26 locus only in cells that are also expressing Cre (Figure 1A) (28). Double transgenic mice (Bmi1 CreER/+; R26 lacZ) were orally gavaged at 3–6 weeks of age with tamoxifen for three consecutive days to induce Cre-mediated recombination. We harvested the pancreata and duodenum from all mice 1 week following tamoxifen administration (scheme in Figure 1B, n = 3). The vast majority of LacZ + cells in the pancreas were single acinar cells, as described previously (16) (Figure 1C). We also observed isolated LacZ + cells in the pancreatic islets, consistent with the previously described role of BMI1 in β-cell homeostasis (14) (data not shown). In the duodenum, LacZ + cells lined the mucosal epithelium extending from the crypts to the tips of the villi presumably originating from BMI1+ crypt stem cells, as described previously (Figure 1C) (27). Thus, BMI1 is expressed in a subset of pancreatic exocrine and endocrine cells.

Figure 1.

Bmi1-expressing cells can serve as a cell of origin for pancreatic cancer. (A) Genetic make up of Bmi1-IRES-CreER;R26 lacZ mice. (B) Experimental design. (C) BMI1+ cells identified by β-Gal staining for the LacZ reporter. (D) Genetic make up of Bmi1-IRES-CreER;Kras LSL-G12D mice. (E) Experimental design. (F) H&E, PAS staining and phosphorylated ERK immunohistochemistry of Bmi1-IRES-CreER;Kras LSL-G12D tissues 3w following pancreatitis.

To determine whether BMI1+ cells in the pancreas can serve as cells of origin for pancreatic cancer, we generated Bmi1 CreER/+ ;Kras LSL-G12D mice, where oncogenic KrasG12D expression can be induced specifically in Bmi1-expressing cells upon Crerecombination (Figure 1D). We treated mice at 3–6 weeks of age with tamoxifen as before. One week later, we induced acute pancreatitis with intraperitoneal injections of the cholecystokinin analog caerulein, as described previously (24). The pancreata were harvested 3 weeks after the induction of pancreatitis (scheme in Figure 1E, n = 4). As expected, control mice had undergone tissue repair within this time frame with full recovery of normal pancreatic histology (data not shown). In contrast, in Bmi1 CreER/+ ;Kras LSL-G12D mice, we observed low-grade PanIN lesions, positive for mucin accumulation as identified by Periodic Acid Schiff staining (PAS), in a sporadic manner through the tissue, consistent with mosaic induction of Cre activation. The lesions were also positive for phosphorylated ERK and were surrounded by fibro-inflammatory stroma (Figure 1F). Therefore, our data indicate that PanIN lesions can arise from BMI1+ cells within the adult mouse pancreas.

Bmi1 is required for pancreatic carcinogenesis

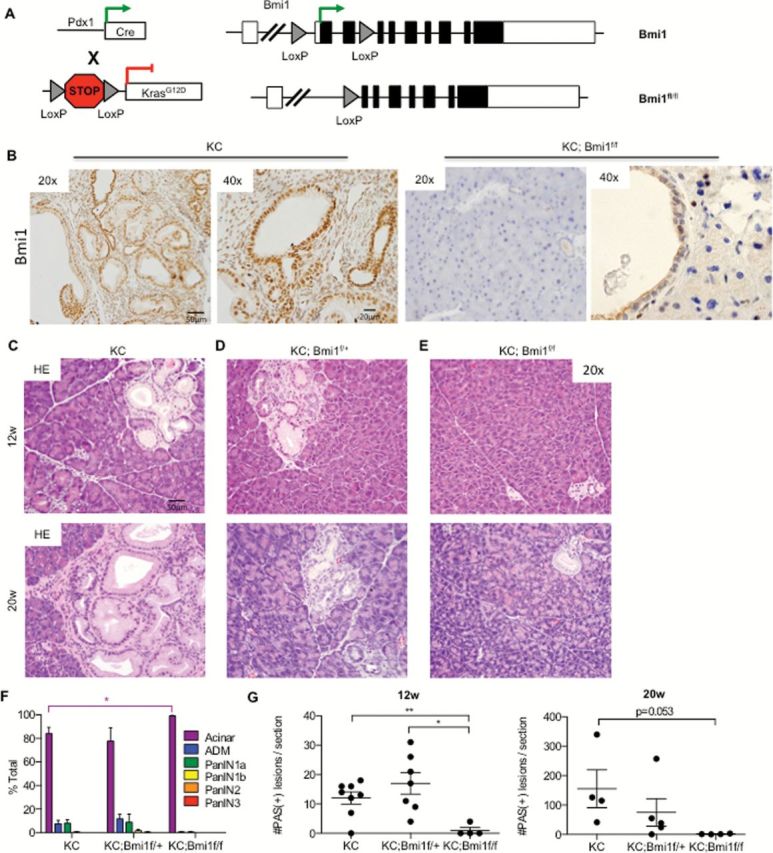

To address the requirement for Bmi1 in murine pancreatic neoplasia, we crossed the Pdx1-Cre;Kras LSL-G12D/+ (KC) mouse model of pancreatic cancer (3) with a novel conditional knockout of Bmi1 (Bmi1 fl/fl) (23) (Figure 2A) to generate Pdx1-Cre;Kras LSL-G12D/+ ;Bmi1 fl/fl (KC; Bmi1 fl/fl) mice. Recombination of the Bmi1 locus in the pancreas was verified by PCR of pancreatic genomic DNA isolated from Pdx1-Cre;Bmi1 +/+, Pdx1-Cre;Bmi1 fl/+ and Pdx1-Cre;Bmi1 fl/fl mice (Supplementary Figure 2 is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Additionally, Bmi1 was expressed in PanINs in KC pancreata, but not in the pancreas of KC;Bmi1 fl/fl mice (Figure 2B). Bmi1 expression was similarly observed in PanINs in Pdx1Cre;KrasLSL-G12D; p53R172H/+ (KPC) mice, a model that combines Kras and p53 mutations and develops PanINs at an earlier age than KC mice (Supplementary Figure 3 is available at Carcinogenesis Online) (4). To investigate PanIN formation, we analyzed KC;Bmi1 fl/fl mice along with KC and KC;Bmi1fl/+ littermates at 12 and 20 weeks after birth (n = 4–8 mice/genotype/time point). KC mice developed PanIN lesions with the expected progression: rare lesions were present at 12 weeks, but abundant lesions were observed at 20 weeks (Figure 2C). KC;Bmi1 fl/+ mice had similar PanIN development to KC animals, with a comparable number and grade of lesions (Figure 2D). The vast majority of the lesions were classified as PanIN1A/1B and PanIN2 (Figure 2F) that presented with characteristic high proliferation index as measured by Ki67+ immunostaining (Supplementary Figure 4A and B is available at Carcinogenesis Online) and intracellular accumulation of mucin (Figure 2G, Supplementary Figure 4D and E is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Strikingly, PanIN formation was almost completely abrogated in KC;Bmi1 fl/fl mice (Figure 2E and F and Supplementary Figure 4C and F is available at Carcinogenesis Online), with a single PanIN1A observed in a single animal. These results implicate BMI1 as a key factor in the initiation of murine pancreatic neoplasia.

Figure 2.

Bmi1 is required for PanIN formation. (A) Genetic make up of Pdx1-Cre;Kras LSL-G12D/+ ;Bmi1 fl/fl (KC; Bmi1 fl/fl) mice. (B) IHC staining for Bmi1 in KC and KC; Bmi1 fl/fl mice. H&E staining for (C) KC, (D) KC;Bmi1fl/+ and (E) KC;Bmi1fl/fl mice at 12 and 20 weeks. Histopathological analysis (2 way analysis of variance: *P < 0.05) (F) and quantification of the number of PAS+ lesions (Student’s t-test: **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05) (G) of KC, KC;Bmi1fl/+ and KC;Bmi1fl/fl mice at 12 and 20 weeks (n = 3–6 mice/genotype/time point).

The induction of acute pancreatitis synergizes with expression of oncogenic Kras to drive PanIN formation (29–31). In the next series of experiments, we investigated whether Bmi1 expression was required in pancreatitis-induced carcinogenesis. For this purpose, we induced acute pancreatitis with the cholecystokinin analog caerulein, as described previously (24), starting 3–4 weeks after birth and collected the pancreatic tissues at time points ranging from 24h to 3 weeks later (n = 3–10 mice/genotype/time point, (scheme in Supplementary Figure 5A is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Wild-type pancreata demonstrated acinar damage and acinar-ductal metaplasia, accompanied by transient upregulation of the MAPK signaling pathway 24h after pancreatitis (Supplementary Figure 5B is available at Carcinogenesis Online) and exhibited complete tissue recovery 3 weeks later (Supplementary Figure 5F is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Analysis of KC, KC;Bmi1fl/+ and KC;Bmi1fl/fl mice, 24h after pancreatitis induction (Supplementary Figure 5C–E is available at Carcinogenesis Online), revealed increased acinar damage and elevated p-ERK1/2 staining, consistent with previous observations in mice expressing oncogenic Kras (24). The prevalence of inflammatory cell infiltration and of acinar damage and the induction of phosphorylated-ERK1/2 in the acinar cells did not differ based on the Bmi1 status of the tissues. Thus, epithelial Bmi1 expression did not affect the early response to caerulein-induced pancreatitis.

Three weeks after pancreatitis, in both KC and KC;Bmi1 fl/+ mice, the pancreas parenchyma was largely replaced by low-grade PanIN lesions surrounded by desmoplastic stroma (Supplementary Figure 5G, H and J is available at Carcinogenesis Online). In contrast, KC;Bmi1fl/fl pancreata presented with almost completely normal acinar and ductal architecture (Supplementary Figure 5I and J is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Rarely, acinar-ductal metaplasia was observed in isolated areas of a subset of the KC;Bmi1fl/fl mice, but frank PanINs were generally absent. These areas of acinar-ductal metaplasia in KC;Bmi1fl/fl mice stained positive for Bmi1, indicating failure to recombine both alleles of Bmi1 rather than an ability to circumvent the requirement of Bmi1 in PanIN initiation (Supplementary Figure 6 is available at Carcinogenesis Online). p-ERK1/2 levels were elevated both within the lesions and in the surrounding stroma of KC and KC;Bmi1 fl/+ pancreata, as well as in the rare areas of ADM in KC;Bmi1fl/fl pancreata (Supplementary Figure 5G–I is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Thus, although the inflammatory response and the pancreatitis-induced tissue damage were not dependent on epithelial BMI1 expression, the subsequent development of PanINs required at least one wild-type Bmi1 allele.

BMI1 controls pancreatic neoplasia independently of Ink4a/ARF

BMI1 has been shown to repress the Ink4a/Arf locus, which encodes for the cell cycle regulators p16INK4A and p19ARF (9). Inactivation of p16 expression is essential to bypass oncogenic Kras-induced senescence and thus for the onset of carcinogenesis (30,32). Thus, we considered the hypothesis that Bmi1 was required to suppress the Ink4a/ARF locus, therefore allowing the onset of pancreatic neoplasia. We used two complementary approaches to address this hypothesis.

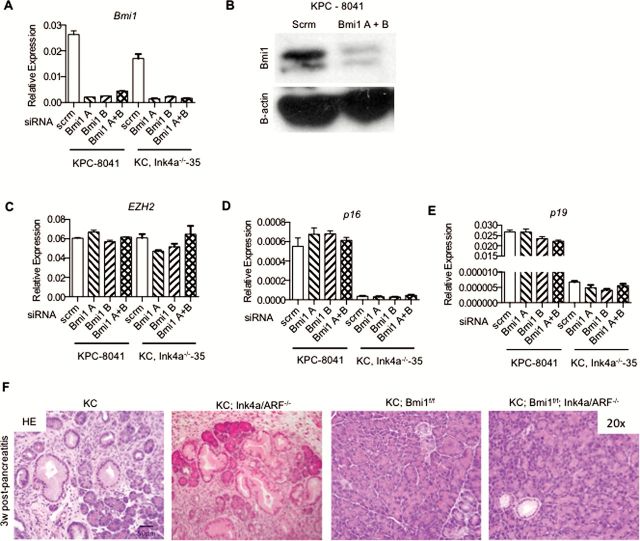

First, we utilized primary low passage mouse pancreatic tumor cell lines derived from p48/Ptfa-1 Cre/+ ;Kras LSL-G12D/+ ;Trp53 R172H/+ (KPC mice) (4) and Pdx1 Cre/+ ;Kras LSL-G12D/+ ;Ink4a −/−, which lack expression of both Ink4a and ARF, (KC;Ink4a −/−) (1) to determine whether inhibition of Bmi1 expression led to derepression of the Ink4a/ARF locus. Multiple independent cell lines were used for each genotype (KPC: 8041, 8206, 65671; KC;Ink4a −/− : 35, 45). We transfected two distinct Bmi1-specific siRNAs individually or in combination into the cell lines to inhibit Bmi1 expression. The siRNA treatment resulted in a >60–80% knockdown of Bmi1 expression across all of the cell lines, as determined by both qPCR (Figure 3A) and western blot (Figure 3B, full blot seen in Supplementary Figure 7 available at Carcinogenesis Online). In comparison, the expression of Ezh2, a component of the polycomb repressor complex 2, was not affected (Figure 3C). We then analyzed the expression of both p16 Ink4a and p19 Arf in the presence and absence of BMI1. Despite robust Bmi1 knockdown, no significant changes in p16/p19 expression were noted in the KPC tumor-derived cell lines (Figure 3D and E). As expected, the cell lines derived from the KC;Ink4a −/− mice did not demonstrate any p16/p19 expression regardless of the presence or absence of Bmi1 (Figure 3D and E). These results suggest that Bmi1 may exert its role in pancreatic neoplasia independently of its regulation of the Ink4a/ARF locus.

Figure 3.

Bmi1-regulated pancreatic carcinogenesis is independent of Ink4a/ARF expression. RT–qPCR (A) and western blot (B) for Bmi1. RT–qPCR for (C) EZH2, (D) p16 and (E) p19. (F) H&E staining for KC, KC;Ink4a/ARF−/−, KC;Bmi1fl/fl and KC;Bmi1fl/fl; Ink4a/ARF−/− pancreata.

Second, to determine whether the requirement for Bmi1 during the onset of pancreatic carcinogenesis was mediated by its ability to repress the Ink4a/ARF locus, we generated KC;Bmi1fl/fl;Ink4a −/− mice. The KC;Ink4a −/− model of pancreatic cancer develops advanced neoplastic lesions rapidly even in the absence of pancreatitis (1,22). KC, KC;Ink4a−/−, KC;Bmi1fl/fl and KC;Bmi1fl/fl ;Ink4a −/−, mice were treated with caerulein to induce pancreatitis, and the pancreata were harvested 3 weeks later (n = 3–5 mice/genotype/time point). As expected, KC and KC;Ink4a−/− mice had extensive PanIN formation at this time point; however, neither KC;Bmi1fl/fl nor KC;Bmi1fl/fl;Ink4a −/− mice presented with lesions (Figure 3F). Bmi1 inactivation abrogated PanIN formation even in Ink4a null animals, indicating that the requirement for BMI1 during the onset of pancreatic carcinogenesis is independent of its regulation of the Ink4a/ARF locus.

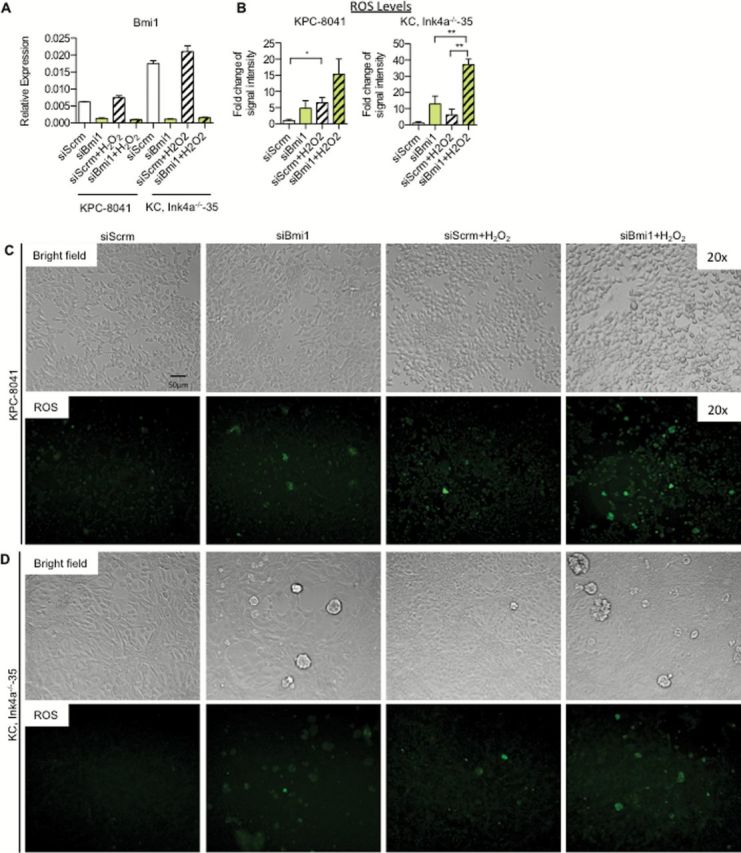

BMI1 deficiency impairs the ROS detoxification program in pancreatic tumor cells

BMI1 regulates the detoxification of ROS generated in the mitochondria and the subsequent induction of the DDR pathway in hematopoietic stem cells and thymocytes (13). ROS detoxification is an essential step during the onset of pancreatic cancer (21). To determine whether Bmi1 was required for ROS regulation in pancreatic cancer cells, we measured ROS levels in mouse primary pancreatic cancer cells upon siRNA-mediated Bmi1 inactivation. We measured the baseline ROS levels and those induced by H2O2 exposure in control and Bmi1-knockdown cells. As before, Bmi1 expression was inhibited with high efficiency (Figure 4A). At baseline, before any H2O2 exposure, the control cells demonstrated a trend toward lower levels of ROS compared with cells with Bmi1 knockdown (Figure 4B). Once the cells were exposed to 500 μM of H2O2, there was a significant increase in the production of intracellular ROS within 2h of the exposure (Figure 4B–D). Under these conditions, the Bmi1-knockdown cells accumulated a greater level of intracellular ROS compared with cells transfected with control siRNA. These results provide the first evidence that BMI1 is required for the regulation of ROS generation in pancreatic tumor cells.

Figure 4.

Activation of ROS detoxification is regulated by Bmi1. (A) RT–qPCR analysis for Bmi1 expression. (B) Quantification of ROS intensity for KPC—8041 cells and KC;Ink4a−/−—35 cells. Bright-field and ROS images for (C) KPC—8041 cells and (D) KC;Ink4a−/−—35 cells following siRNA and H2O2 treatments.

Oxidative stress can induce the DDR pathway in cells to protect the integrity of the genome. Chk2, a DDR pathway component, is activated in the thymocytes of Bmi1 knockout mice (13). Furthermore, deletion of Chk2 rescued the defect in survival and body size in Bmi1 knockout mice. Thus, at least during normal organ maintenance, a key function of Bmi1 is to repress the expression of Chk2. To determine the effect of Bmi1 loss on Chk2 expression in our system, we measured expression levels of Chk2, with or without the induction of ROS. Bmi1 knockdown did not appreciably increase Chk2 expression in Bmi1-knockdown cells compared with control, either without or with exposure to ROS as tested by western blot (Supplementary Figure 7A is available at Carcinogenesis Online) or qPCR (Supplementary Figure 7B is available at Carcinogenesis Online). However, the knockdown of Bmi1 significantly reduced the levels of H2AK119Ub at the Chk2 locus. This shows that, at the epigenetic level, we are seeing the changes we would expect as a result of Bmi1 knock down (Supplementary Figure 7C–F is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Similarly, we did not observe expression changes of the antioxidant enzyme Nrf2, in vitro or in vivo (Supplementary Figure 8A and B is available at Carcinogenesis Online), or its binding partner Keap1 (Supplementary Figure 8C is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Finally, we did not observe significant changes in other proteins involved in the DDR, including ATM and BRCA1 (Supplementary Figure 8D and E is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Therefore, Bmi1 loss-induced ROS generation but did not cause a subsequent induction of the DDR pathway.

Discussion

Our work is the first study addressing the role of Bmi1 during pancreatic carcinogenesis in the context of an intact microenvironment. Our results provide the first direct evidence that BMI1 is required for pancreatic cancer initiation.

We used genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic cancer combined with tissue-specific inactivation of Bmi1 to study the role of BMI1 in the initiation and progression of pancreatic neoplasia. When Bmi1 was inactivated in the pancreas, neoplastic transformation did not occur in either the KC;Bmi1fl/fl or the KC;Bmi1fl/fl;Ink4a −/− mice. Thus, BMI1 is required for the establishment and survival of pancreatic neoplastic cells and this process is independent of Bmi1 control of the Ink4a/ARF locus. Bmi1 requirement in the initiation of neoplasia recapitulates previous observations in a KRAS-driven mouse model of lung cancer (33). However, in that case, the inhibition of lung neoplastic transformation was dependent on the upregulation of p19 Arf from the Ink4a/ARF locus. In contrast, we find that the tumor-promoting role of BMI1 in pancreatic cancer is independent of the status of the Ink4a/ARF locus. Bmi1 control of cancer initiation independent of Ink4a expression has been reported previously in an orthotopic transplantation model of glioma (34). Therefore, BMI1 may regulate tumorigenesis differently depending on the tissue context, indicating the need for tissue-specific studies.

PRCs play a key role in the regulation of multiple cancers (35). One of the other most studied components is EZH2, a member of PRC2 which also plays an integral role in gene silencing (36). BMI1 and EZH2 are classically thought to cooperate in gene silencing. However, our results following Bmi1 deletion are in stark contrast with the analysis of p48-Cre, Kras LSL-G12D/+ mice, where Ezh2 is genetically inactivated (37). In KC mice lacking Ezh2 expression, loss of Ezh2 led to a rapid onset of PanINs and early mortality by 12–16 weeks. In this model, EZH2 acted at least partially through the Ink4a/ARF locus, which led to the inability of the acinar compartment to recover from transient injury. This effect was compounded by an increased inflammatory infiltrate resulting in additional injury and early fibrosis and neoplasia (37). In contrast, our Bmi1 knockout mice demonstrated complete abrogation of pancreatic neoplasia under both caerulein-induced pancreatitis and quiescent conditions. These results highlight the complex roles of the different PRCs in pancreatic neoplasia and the need for further exploration of the epigenetic regulation mechanisms controlling pancreatic transformation.

BMI1 plays a role in additional cellular processes, including the dysregulation of ROS generation (13). Our experiments revealed increased ROS generation in pancreatic cancer cells when Bmi1 expression was inhibited. However, ROS accumulation did not correlate with upregulation of CHK2 or changes in other components of the DDR pathway. In conclusion, BMI1 upregulation observed in early PanINs may represent a protective response of transformed cells to KRAS-driven oxidative stress. Interestingly, activation of a ROS detoxification program has been recently shown to be an essential step during the onset of pancreatic carcinogenesis (21), and inactivation of the key ROS detoxification component Nrf2 was sufficient to inhibit carcinogenesis. However, given the complexity of the epigenetic regulation in pancreatic cancer, it is likely that Bmi1 exerts its role in carcinogenesis through regulation of multiple pathways, warranting further investigation in the future. Importantly, recent pre-clinical testing of a Bmi1 inhibitor slowed tumor growth in a colon cancer xenograft model, revealing Bmi1’s potential as a therapeutic target (38). Together with previous work indicating a role for Bmi1 in the growth of human pancreatic cancer cells in an orthotopic transplantation model in immunocompromised mice (18), our observations provide rationale for Bmi1 inhibition as a potential therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Table 1 and Figures 1–8 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

F.B. was supported by the American College of Surgeons Resident Research Scholarship and by National Institutes of Health (NIH T32 HD007505). H.K.S. is supported by a University of Michigan Program in Cellular and Molecular Biology Training Grant (NIH T32 GM07315). M.A.C. was supported by a University of Michigan Program in Cellular and Molecular Biology Training Grant (NIH T32 GM07315), a University of Michigan Center for Organogenesis Training Grant (5-T32-HD007515). Research in the Pasca di Magliano lab is supported by National Cancer Institute (1R01CA151588-01), by American Chemical Society (RSG-14-173-01-CSM) and by the Elsa Pardee Foundation. This project was supported by a National Pancreas Foundation Pilot Grant. L.L.A. and M.E.F-Z. are supported by Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology Grant (DK84567). K.P.O. is supported by NIH 1R21CA188857.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BMI1

B-cell-specific Moloney murine leukemia virus insertion site 1

- DDR

DNA damage response

- PDA

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- pERK

phosphorylated extracellular signal-related kinase

- PRCs

polycomb repressive complexes

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- siRNAs

small interfering RNAs

References

- 1. Aguirre A.J., et al. (2003) Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev., 17, 3112–3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guerra C., et al. (2007) Chronic pancreatitis is essential for induction of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by K-Ras oncogenes in adult mice. Cancer Cell, 11, 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hingorani S.R., et al. (2003) Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell, 4, 437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hingorani S.R., et al. (2005) Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell, 7, 469–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones S., et al. (2008) Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science, 321, 1801–1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berdasco M., et al. (2010) Aberrant epigenetic landscape in cancer: how cellular identity goes awry. Dev. Cell, 19, 698–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schuettengruber B., et al. (2007) Genome regulation by polycomb and trithorax proteins. Cell, 128, 735–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Lohuizen M., et al. (1991) Identification of cooperating oncogenes in E mu-myc transgenic mice by provirus tagging. Cell, 65, 737–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacobs J.J., et al. (1999) The oncogene and Polycomb-group gene bmi-1 regulates cell proliferation and senescence through the ink4a locus. Nature, 397, 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Lugt N.M., et al. (1994) Posterior transformation, neurological abnormalities, and severe hematopoietic defects in mice with a targeted deletion of the bmi-1 proto-oncogene. Genes Dev., 8, 757–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Molofsky A.V., et al. (2005) Bmi-1 promotes neural stem cell self-renewal and neural development but not mouse growth and survival by repressing the p16Ink4a and p19Arf senescence pathways. Genes Dev., 19, 1432–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bruggeman S.W., et al. (2005) Ink4a and Arf differentially affect cell proliferation and neural stem cell self-renewal in Bmi1-deficient mice. Genes Dev., 19, 1438–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu J., et al. (2009) Bmi1 regulates mitochondrial function and the damage response pathway. Nature, 459, 387–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dhawan S., et al. (2009) Bmi-1 regulates the Ink4a/Arf locus to control pancreatic beta-cell proliferation. Genes Dev., 23, 906–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fukuda A., et al. (2012) Bmi1 is required for regeneration of the exocrine pancreas in mice. Gastroenterology, 143, 821–831.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sangiorgi E., et al. (2009) Bmi1 lineage tracing identifies a self-renewing pancreatic acinar cell subpopulation capable of maintaining pancreatic organ homeostasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 7101–7106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martínez-Romero C., et al. (2009) The epigenetic regulators Bmi1 and Ring1B are differentially regulated in pancreatitis and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Pathol., 219, 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Proctor E., et al. (2013) Bmi1 enhances tumorigenicity and cancer stem cell function in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PLoS One, 8, e55820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song W., et al. (2010) Bmi-1 is related to proliferation, survival and poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci., 101, 1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tateishi K., et al. (2006) Dysregulated expression of stem cell factor Bmi1 in precancerous lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. Clin. Cancer Res., 12, 6960–6966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. DeNicola G.M., et al. (2011) Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature, 475, 106–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bardeesy N., et al. (2006) Both p16(Ink4a) and the p19(Arf)-p53 pathway constrain progression of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 5947–5952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mich J.K., et al. (2014) Prospective identification of functionally distinct stem cells and neurosphere-initiating cells in adult mouse forebrain. Elife, 3, e02669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Collins M.A., et al. (2012) Oncogenic Kras is required for both the initiation and maintenance of pancreatic cancer in mice. J. Clin. Invest., 122, 639–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hruban R.H., et al. (2006) Pancreatic cancer in mice and man: the Penn Workshop 2004. Cancer Res., 66, 14–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mathew E., et al. (2014) The transcription factor GLI1 modulates the inflammatory response during pancreatic tissue remodeling. J. Biol. Chem., 289, 27727–27743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sangiorgi E., et al. (2008) Bmi1 is expressed in vivo in intestinal stem cells. Nat. Genet., 40, 915–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Soriano P. (1999) Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet., 21, 70–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morris J.P., 4th, et al. (2010) Beta-catenin blocks Kras-dependent reprogramming of acini into pancreatic cancer precursor lesions in mice. J. Clin. Invest., 120, 508–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guerra C., et al. (2011) Pancreatitis-induced inflammation contributes to pancreatic cancer by inhibiting oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer Cell, 19, 728–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carrière C., et al. (2011) Acute pancreatitis accelerates initiation and progression to pancreatic cancer in mice expressing oncogenic Kras in the nestin cell lineage. PLoS One, 6, e27725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee K.E., et al. (2010) Oncogenic KRas suppresses inflammation-associated senescence of pancreatic ductal cells. Cancer Cell, 18, 448–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dovey J.S., et al. (2008) Bmi1 is critical for lung tumorigenesis and bronchioalveolar stem cell expansion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 11857–11862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bruggeman S.W., et al. (2007) Bmi1 controls tumor development in an Ink4a/Arf-independent manner in a mouse model for glioma. Cancer Cell, 12, 328–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sparmann A., et al. (2006) Polycomb silencers control cell fate, development and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 6, 846–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cao R., et al. (2002) Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science, 298, 1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mallen-St Clair J., et al. (2012) EZH2 couples pancreatic regeneration to neoplastic progression. Genes Dev, 26, 439–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kreso A., et al. (2014) Self-renewal as a therapeutic target in human colorectal cancer. Nat. Med., 20, 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.