Background: At least six synaptic vesicle (SV) membrane proteins must be endocytosed and sorted during SV recycling.

Results: Loss of vGlut1 slows endocytosis kinetics of many other SV proteins, whereas impairing vGlut1 slows other cargos.

Conclusion: vGlut1 plays a central role in coordinating SV cargo endocytosis.

Significance: SV recycling is essential for synaptic transmission and relies on collective behavior of many cargo proteins.

Keywords: neuron, endocytosis, membrane recycling, microscopic imaging, synapse, vesicles, vGlut, protein sorting, gene silencing, glutamate transporter

Abstract

A long standing question in synaptic physiology is how neurotransmitter-filled vesicles are rebuilt after exocytosis. Among the first steps in this process is the endocytic retrieval of the transmembrane proteins that are enriched in synaptic vesicles (SVs). At least six types of transmembrane proteins must be recovered, but the rules for how this multiple cargo selection is accomplished are poorly understood. Among these SV cargos is the vesicular glutamate transporter (vGlut). We show here that vGlut1 has a strong influence on the kinetics of retrieval of half of the known SV cargos and that specifically impairing the endocytosis of vGlut1 in turn slows down other SV cargos, demonstrating that cargo retrieval is a collective cargo-driven process. Finally, we demonstrate that different cargos can be retrieved in the same synapse with different kinetics, suggesting that additional post-endocytic sorting steps likely occur in the nerve terminal.

Introduction

To ensure effective neural signaling by activity-driven neurotransmitter release, a repertoire of synaptic vesicle (SV)2 proteins needs to be retrieved in a timely fashion to meet the needs of subsequent signaling events. Numerous studies have demonstrated that this process occurs through a dynamin- (1), clathrin- (2), and AP-2-dependent (3) process, suggesting that SV membrane proteins likely follow pathways that have been delineated for endocytic retrieval of “classical” cargos such as the transferrin or the LDL receptor (4). Following exocytosis at nerve terminals, however, at least six families of SV membrane proteins potentially intermix with presynaptic membrane resident proteins and await resorting, translocation, endocytosis into a new endocytic organelle, and ultimately, refilling with neurotransmitter in preparation for the next round of fusion (5–8). Among the SV proteins are: the vesicular SNARE VAMP2, the calcium sensor synaptotagmin 1 (Syt1), the tetra-spanning membrane protein synaptophysin (Syphy), the multi-spanning membrane protein SV2, the vesicular neurotransmitter transporter (vGlut for glutamatergic neurons), and the V-type ATPase proton pump. To date, classic endocytosis motifs (di-leucine- and tyrosine-based motifs) have been identified for few of these SV proteins, raising the question of how clathrin and its adaptor complexes recruit the full complement of cargos during endocytosis. One possibility is that different adaptor proteins, such as AP-2, AP180, and stonin 2, provide specificity for membrane cargo during endocytosis. Another possibility is that specific cargo molecules that have well defined interactions with endocytic adapters themselves orchestrate the retrieval of others. The latter possibility has been suggested for some SV cargo proteins (9, 10). We wondered whether any specific SV protein might have an influence on a majority of the other cargos. Proteomic analysis (11) revealed that SVs contain an average of 70 copies of VAMP, 30 copies of Syphy, 15 copies of Syt1, ∼9–14 copies of the relevant vesicular neurotransmitter transporter (vGlut1 for hippocampal and cortical glutamatergic neurons), and only 1–2 copies of SV2 and the V-type ATPase. pHluorin-based tagging of the luminal aspects of SV cargo proteins provides a quantitative approach to examine the endocytic retrieval kinetics following a burst of exocytosis (12–14). In addition, the steady-state accumulation of the tagged proteins on the synaptic surface provides an indirect measure of the relative efficacy of the endocytic machinery for these cargos. We find that of the five main SV cargos (out of six) tested, vGlut1 has the lowest steady-state surface accumulation and therefore likely is endocytosed with the greatest efficacy following exocytosis. We therefore went on to test the hypothesis that this particular SV cargo protein might have a strong influence on the internalization of other cargos. We did this in four ways. First, we examined the impact of ablating vGlut1 expression on the endocytosis of two native SV cargos using an antibody labeling approach after stimulation. Second, we examined the impact of ablating vGlut1 expression on the detailed kinetics of the remaining SV cargos using pHluorin-tagged SV cargo proteins. Third, we examined the impact of expressing a slowly endocytosing mutant of vGlut1 on the endocytosis kinetics of other SV cargos. Fourth, we examined how this slowly endocytosing mutant impacts endocytosis of WT vGlut1 when present in the same synapse.

Our experiments demonstrated that vGlut1 has a strong influence on endocytosis of other SV cargos, but appears to act autonomously of other copies of vGlut1. These results support a model whereby vGlut1 plays an important role in coordinating endocytosis of other SV cargos. Thus unlike classical endocytosis, where cargo molecules are thought to dictate their own endocytic fate, SV cargos operate in a more collective manner.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture and Optical Setup

Hippocampal CA3-CA1 regions without dentate gyrus were dissected from 1–3-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats, dissociated, and plated onto poly-ornithine-coated glass coverslips as described previously (15). Constructs were transfected between days in vitro 7–8 by calcium phosphate, and experiments were carried out 6–12 days after transfection.

For live cell imaging, cells on coverslips were mounted on a custom-made laminar-flow stimulation chamber with constant perfusion (at a rate of ∼0.2–0.3 ml/min) of Tyrode's salt solution containing (in mm) 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 25 HEPES, 30 glucose, 10 μm 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, 50 μm d,l-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid and buffered to pH 7.4. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise noted. Temperature was clamped at 30.0 °C using a resistive microscope objective heater with feedback control throughout the experiment. 1-ms 10 V/cm field stimuli were used to evoke single action potentials delivered using an A310 Accupulser and A385 stimulus isolator (World Precision Instruments). Images were acquired through a 40× Zeiss Fluar objective onto a back-illuminated EM-CCD (iXon+ model number DU-897E-BV, Andor USA, South Windsor, CT). The perfusion/stimulation/imaging chamber was mounted on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope modified for wide-field laser illumination. For single color imaging, a solid-state diode-pumped 488-nm laser was shuttered using acoustic-optic tunable filters during non-data-acquiring periods at 2-Hz acquisition. For dual-color imaging of mOrange2 and pHluorin, a 488-nm laser and a 532-nm laser were modulated sequentially by a custom-made switcher circuit while images were collected at 4 Hz (2-Hz acquisition for each channel) using a custom-made dual filter set (488/532-laser filter set) from Chroma. In some experiments, GABAergic neurons were identified at the end of the experiment by loading Oyster-550-labeled rabbit anti-vGAT (vesicular GABA transporter, 3.33 μg/ml, Synaptic Systems catalog number 131 103C3) using 1200 action potentials (AP) at 10-Hz stimulation.

Antibody-based Labeling of Recycling Native SV Proteins

At days in vitro 14–16, these cells were transferred to Tyrode's solution and subjected to two rounds of 10 Hz, 10 s of field stimulation separated by 5 min, the first of which was used to increase exocytosis efficiency. The second stimulus was followed 10 s later by perfusion with a luminal antibody either against synaptophysin (G96 serum, 1:75 dilution, gift of Dr. Reinhard Jahn at Max Planck Institute, Gottingen, Germany) or against synaptotagmin 1 (Oyster-550-labeled anti-Syt1, clone 604.2, luminal domain, 1:100 dilution, Synaptic Systems catalog number 105 311C3). After a 5-min incubation, the unbound antibody was washed out in Tyrode's solution for 10 min (see Fig. 2A). Cells were then fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde and immunostained using chicken anti-GFP (1:1000, Invitrogen, catalog number A10262), and guinea pig anti-synapsin I (1:1000, Synaptic Systems catalog number 106 004) for 1 h at 37 °C. The following secondary antibodies were applied: goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 546 (1:500) for G96; goat anti-chicken Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000) for GFP; and goat anti-guinea pig Alexa Fluor 647 (1:500) for synapsin I. Due to the unavailability of a good marker for GABAergic neuron identification (which should be purified from a different animal species for co-immunoreactivity), we examined the percentage of glutamatergic neurons in an additional experiment using rabbit anti-GABA (1:500, Sigma, catalog number A2052). We found that GABAergic neurons only represent 10–20% of total neurons in our culture.

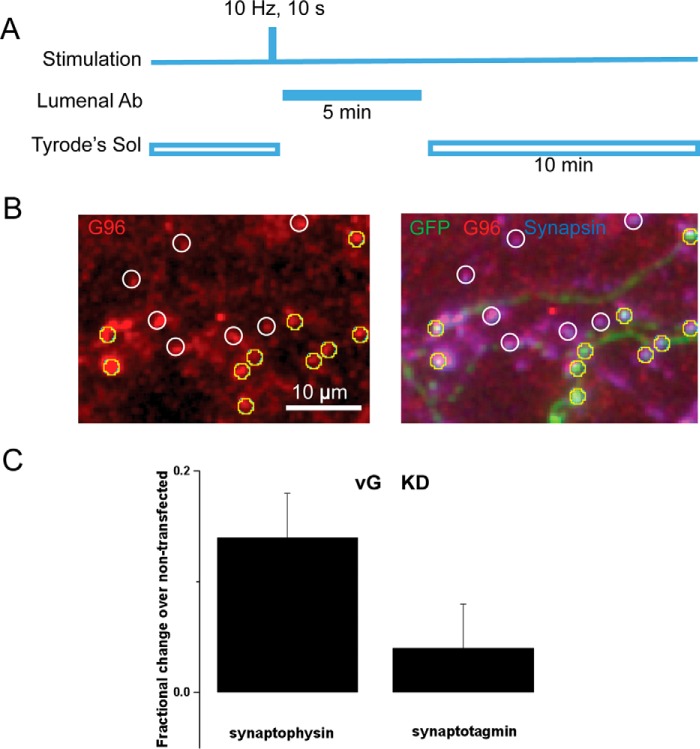

FIGURE 2.

vGlut deficiency slows the synaptic activity-driven recycling of endogenous synaptophysin but synaptotagmin. A, illustration of the experimental protocol (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). Cells were stimulated for 10 s at 10 Hz and followed 10 s after the end of the stimulus by perfusion with a luminal antibody either against synaptophysin (G96 serum) or against synaptotagmin 1 (Oyster-550-labeled anti-Syt1). After a 5-min incubation, the unbound antibody was washed out in Tyrode's solution (Tyrode's Sol) for 10 min, fixed, permeabilized, and stained with secondary and other antibodies. B, a representative image of G96 serum-labeled boutons (left) and its overlay image with GFP in green and synapsin I in blue (right). GFP-positive boutons (yellow circles) and GFP-negative boutons (white circles) were selected based on positive synapsin I staining when the luminal antibody channel was blinded. C, for each randomly selected imaging field containing both GFP-positive and GFP-negative boutons, the fluorescence intensity of the lumenal antibody at the GFP-positive bouton was normalized to the averaged fluorescence intensity of control boutons in the same field. VGlut1 deficiency (vG KD) resulted in 13.7 ± 4.4% increase in synaptophysin (Syphy) staining (n = 12 cells, 224 boutons) when compared with the untransfected control (n = 12 cells, 215 boutons, p = 0.026, paired t test). In contrast, vG KD did not change the synaptotagmin 1 (Syt1) staining (4.1 ± 4.3% increase, n = 11 cells, 125 boutons) relative to its control (n = 11 cells, 163 boutons, p = 0.42, paired t test). Error bars indicate S.E.

DNA Constructs

shRNA targeting vGlut1 was custom-made by OriGene. A 29-mer hairpin was engineered into the pRS vector driven by U6 promoter using the following targeting sequence: 5′-CACTATGGCTGTGTCATCTTCGTGAGGAT-3′. vGlut1-mOrange2 (vG-mO2) was made by cloning mOrange2 using NotI and XhoI enzyme sites with linkers to replace pHluorin in pCAG-vGlut1-pHluorin. vGlut1AA-pHluorin (vGAA-pH) and HA-vGAA were originally gifts from the laboratory of Robert Edwards (University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)). shRNA-resistant vGlut1 was made by PCR using HA-vGAA as the N-terminal template with the following primers: 5′-GGCTGCGTACGAATTCATGGAGTTCCGG-3′, 5′-GATGACGCATCCGTAGTGAACACGGGCT-3′; and vG-pH as the C-terminal template with the following primers: 5′-CACTACGGATGCGTCATCTTCGTGAGGATCC-3′and 5′-GTGCGAATTCTCAGTAGTCCCGGACAGG-3′. N- and C-terminal PCR products were then combined and amplified into a single double-strand DNA and ligated into pCAG with EcoRI sites on both ends. vGAAΔPP2-pHluorin and HA-vGAAΔPP2 were made by adding a stop codon in vGAA-pH and HA-vGAA, respectively, before the second proline-rich domain of vGlut1 using the following primers: 5′-GTGCTTACACGAATTCATGGAGTTCCGG-3′ and 5′-CACACAGCACAGTTCAGTAACTCGAGGTCG-3′. pCI-SV2-pHluorin (SV2-pH) was a gift from the laboratory of Ed Chapman (University of Wisconsin).

Immunocytochemistry and Antibodies

Neurons were fixed in paraformaldehyde buffer (containing 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and 4% sucrose) for 10 min, permeabilized in 0.25% Triton, and blocked with 5% BSA for 40–60 min in 37 °C. Primary antibodies were diluted with 5% BSA and incubated with the cell at 37 °C for 1 h. After a 5-min wash in PBS, cells where incubated with 1:1000 dilution of Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). Guinea pig anti-vGlut1 polyclonal antibody (Millipore, AB1905) was used at 1:1000, followed by goat anti-guinea pig Alexa Fluor 647. Mouse anti-GAD2 (GAD65) monoclonal antibody (Synaptic Systems, catalog number 198111) was used at 1:500, followed by goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 546. pHluorin was stained with chicken anti-GFP (Invitrogen, catalog number A10262), followed by goat anti-chicken Alexa Fluor 488. Immunofluorescence was taken by the camera in a similar way as live cell imaging, except that a mercury arc lamp was used to illuminate Alexa Fluor 647, and immunofluorescence was collected by emission filter 700/D75. A Cy3 narrow band emission filter (585/D40) was used to eliminate bleed-through.

Data Analysis

Images were analyzed in ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) using a custom-written plugin (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/plugins/time-series.html). 2-μm diameter circular regions of interest were placed on all varicosities that appear stable throughout all trials and responded to a maximal stimulus. Only boutons that did not split or merge, remained in focus, and responded throughout all trials were chosen. Between 25 and 50 regions of interest were used per cell. All fitting was done using OriginPro (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. Fits of the endocytosis time constant were single exponential decays with a temporal offset for re-acidification of ∼5 s at 30 °C as described previously (12–14). Data sets with normal distributions were subjected to Student's t test. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used in all other cases. All p values represent two-tailed comparison.

Results

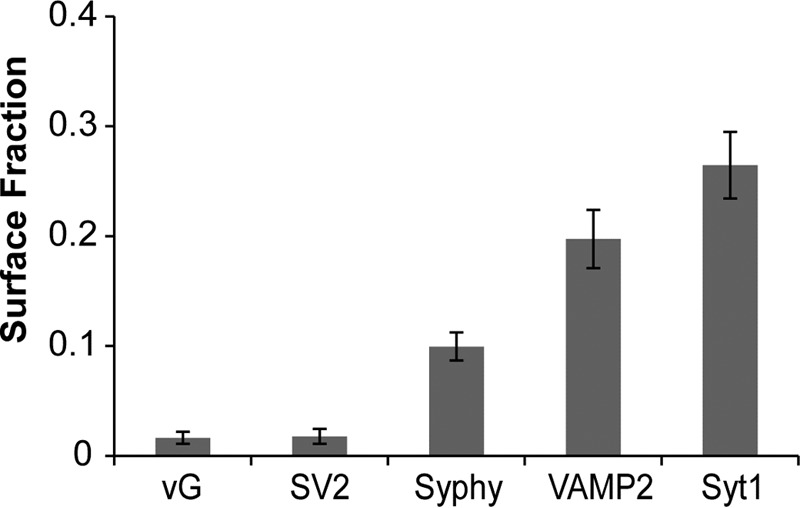

pHluorin tagging of SV proteins provides the ability to quantitatively measure the kinetics of exocytosis, endocytosis, and vesicle re-acidification at nerve terminals as pHluorin is readily quenched by protons in the acidic milieu of the vesicle but is largely unquenched when resident on the synaptic surface (12). The fraction of tagged protein that resides on the presynaptic plasma membrane surface at steady state likely reflects the efficiency of the endocytic machinery for retrieving a given SV cargo. This fraction can be quantified by measuring the change in fluorescence that arises when either elevating the vesicular pH using a pulse of NH4Cl (pH 7.4) or transiently decreasing the external pH with an impermeant acid (12). We used the former approach to systematically examine the steady-state surface fraction of five out of the six major SV proteins when tagged with pHluorin and expressed in dissociated hippocampal neurons. Quantitative analysis of the surface fraction of each of these proteins at nerve terminals is displayed in Fig. 1, which revealed a clear hierarchy in steady-state accumulation for the different SV proteins. vGlut1 had the lowest surface fraction, followed closely by SV2, synaptophysin, VAMP2, and synaptotagmin 1 (Fig. 1). It is interesting to note that this does not represent a simple reflection of the relative native abundance of these proteins because the two SV cargos with the smallest and largest surface fraction have similar abundance in SVs (11).

FIGURE 1.

vGlut has the lowest steady-state presynaptic surface fraction of all SV cargo proteins. Steady-state surface fraction of SV cargos was determined by examining the fractional change in fluorescence in response to brief NH4Cl application at hippocampal synapses expressing SV proteins containing an exofacial/luminal pHluorin tag: vGlut1 (vG, 1.6 ± 0.56%, n = 9), SV2 (1.7 ± 0.7%, n = 8), synaptophysin (Syphy, 9.9 ± 1.3%, n = 10), VAMP2 (19.7 ± 2.6%, n = 8) and synaptotagmin 1 (Syt1, 26.5 ± 3.0%, n = 8). Error bars indicate S.E.

Given that vGlut1 appears to have the highest endocytic clearance efficiency, it seemed poised to potentially have an important controlling influence on the endocytic retrieval of other SV cargos. To examine this, we made use of shRNA-mediated genetic ablation of vGlut1 and examined the impact on the efficiency with which antibodies directed against the luminal domain of either synaptophysin or synaptotagmin were impacted. Expression of an shRNA targeting vGlut1 resulted in 93% suppression of vGlut1 expression in glutamatergic neurons (see Fig. 3A). We reasoned that if loss of vGlut1 might selectively impair endocytosis of one of these SV proteins, then 10 s after the stimulus, a greater fraction of the cargo would be available for labeling with an extracellular antibody. We found that 10 s after a 100-AP stimulus (10 Hz), vGlut1-KD neurons had greater labeling than non-transfected neurons in the same field of view. This amounted to a 14% ± 4% increase when compared with non-transfected neurons (n = 12, p < 0.02). In contrast, no such difference was observed using the anti-synaptotagmin antibody (4% ± 4%, n = 11, p = 0.42).

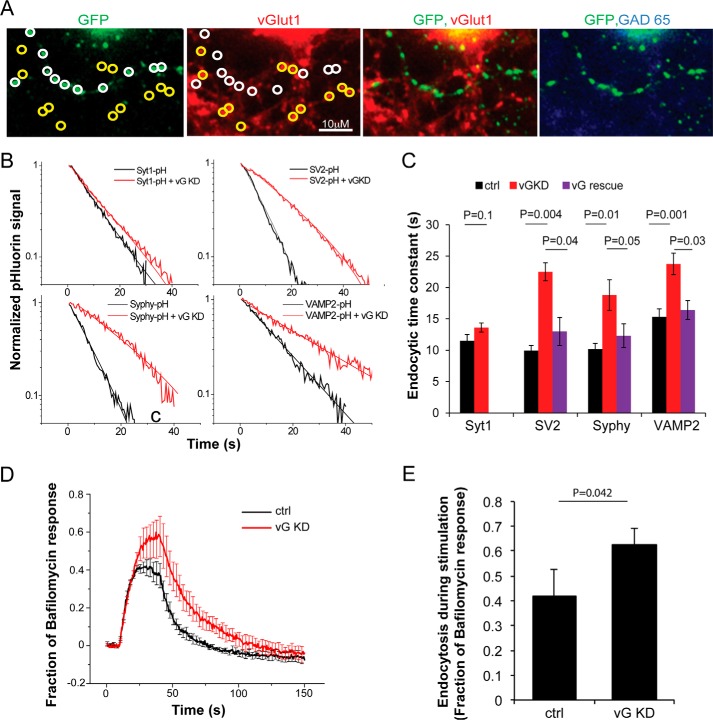

FIGURE 3.

vGlut modulates endocytic retrieval of 3 different SV cargos at nerve terminals. A, representative presynaptic boutons from a neuron co-expressing a pHluorin-tagged SV protein (stained with anti-GFP) and vGlut1 shRNA. GFP-positive boutons (white circles) show much lower vGlut1 immunofluorescence when compared with neighboring non-transfected boutons (yellow circles). Only neurons that were negative for anti-GAD65 immunoreactivity (right panel) were used in this study (positive GAD-65 puncta were visible on the same coverslip, although not in this field of view). B, decay of SV-pHluorin fluorescence after a 10-s 10 Hz stimulation showing endocytosis kinetics (thick traces) in semi-log format with single-exponential fits (thin lines) measured in vGlut1 knockdown (vG KD, red) and control (black) synapses. C, summary of endocytic time constants for different SV proteins in control (black), vG KD neurons (red), and those expressing shRNA-resistant vG on KD background (vG rescue, purple). The slowed kinetics observed for SV2, Syphy, and VAMP2 was rescued (SV2 rescue, 13.0 ± 2.2, n = 6 when compared with KD: 22.5 ± 1.4 s, n = 9, p = 0.04; Syphy rescue, 12.3 ± 1.9 s, n = 8 when compared with KD: 18.8 ± 2.4 s, n = 8, p = 0.05; VAMP2 rescue, 16.4 ± 1.5, n = 6 when compared with KD: 23.7 ± 1.7 s, n = 11, p = 0.03, Student's t test) by re-expression of vGlut1. D, averaged Syphy-pHluorin traces for a longer stimulus train (10 Hz, 30 s) are shown for WT (control (ctrl), n = 6) and neurons co-expressing vGLUT1 shRNA (vG KD, n = 7). Error bars indicate S.E. E, summary of total fraction of endocytosis during stimulation determined by subtracting the peak response to 10 Hz, 30 s stimulation without bafilomycin (as in D) from the response to the same stimulus in the presence of bafilomycin. Ctrl: 0.42 ± 0.11 when compared with KD: 0.63 ± 0.06, p = 0.04, Student's t test.

However, such antibody labeling experiments are not well suited to extract quantitative detail given that they are based on the need to rapidly label proteins that are in the midst of endocytosis. We therefore turned to a more robust approach for examining kinetics and expressed shRNA targeting vGlut1 in combination with expression of pHluorin-tagged SV proteins. Unlike the antibody-labeling approach, pHluorin provides a real-time readout of the vesicle recycling following AP-driven exocytosis and can be used to extract much more quantitative detail. Removal of vGlut1 had no observable impact on exocytosis for the stimuli used here as judged by comparing the amplitude of the pHluorin response in WT and vGlut1 knockdown (KD) neurons for each of the SV cargos tested (Table 1). We previously demonstrated that following a burst of exocytosis, the decay in SV-pHluorin fluorescence is well fit to a single exponential decay (see Fig. 3B) beginning at a time point offset from the end of the stimulus equal to roughly twice the re-acidification time constant. From this time point on, the exponential time course is dominated by endocytosis (13, 14). After removal of vGlut1, the kinetics of endocytosis of tagged SV cargo proteins following a 100-AP stimulation remained mono-exponential but was significantly slowed for all but one of the cargos tested, Syt1 (see Fig. 3, B and C), in agreement with our observations of native SV proteins (Fig. 2). In each case, normal endocytosis kinetics was restored upon simultaneous expression of an shRNA-resistant variant of vGlut1 (Fig. 3C). The total amount of endocytosis occurring during prolonged stimulation, which can be determined by comparing the rise in SV-pHluorin fluorescence during stimulation with and without the proton pump blocker bafilomycin A (3, 16), was also reduced when endogenous vGlut1 expression was suppressed (Fig. 3, D and E), indicating that there is a defect both during and after activity-driven SV recycling in the absence of vGlut1. The fact that loss of vGlut1 selectively impaired SV2, Syphy, and VAMP but not Syt1 endocytosis indicates that loss of vGlut1 did not likely lead to down-regulated expression of essential endocytic proteins, such as endophilin, AP-2, clathrin, or dynamin, as was verified by immunocytochemistry (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

The peak pHluorin signal to a 100-AP (10-Hz) stimulus is similar for all conditions tested (cargo-pH in WT background, vG KD, or in the presence of vGAA or vGAAΔPP2)

The response magnitude is normalized to the peak response of a brief NH4Cl perfusion on the same neuron.

| Fraction of NH4Cl response | vG-pH | SV2-pH | Syphy-pH | Syt1-pH | VAMP2-pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cargo-pH control | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | |

| Cargo-pH with vG KD | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | |

| Cargo-pH alone | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

| Cargo-pH with HA-vGAA | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.02 |

| Cargo-pH with HA-vGAADPP2 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

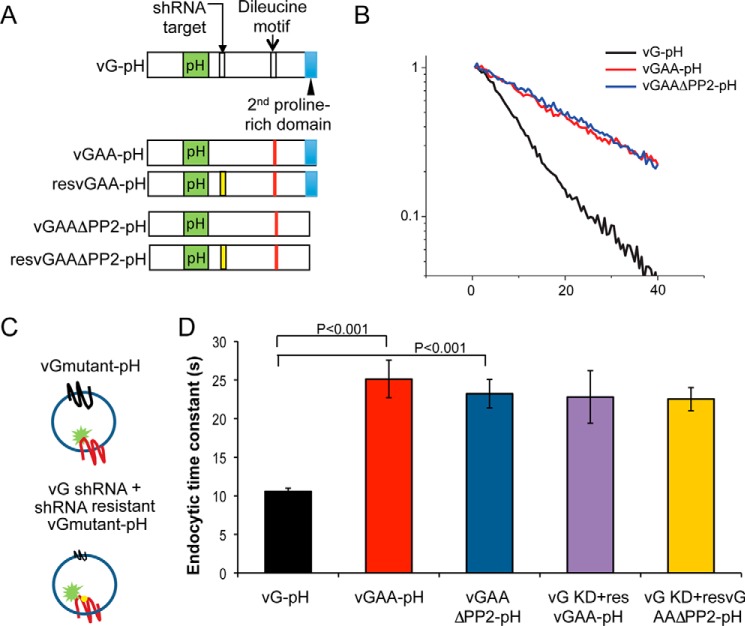

Our third test of the hypothesis that vGlut1 coordinates other SV cargo internalization took advantage of the successful previous identification of a di-leucine motif in vGlut1 (17) (Fig. 4A) that mediates interaction with the α and σ2 subunits of AP-2 (18). Mutating the di-leucine motif (vGAA) significantly impairs endocytosis of this protein measured with pHluorin tagging (17, 19) (Fig. 4, B and D) consistent with the observed endocytic slowing of vGlut1 following shRNA-mediated ablation of AP-2 (3). We also characterized the impact of removing an additional previously identified interaction domain, a poly-proline stretch (ΔPP2) that in vitro eliminates interactions with the SH3 domain of endophilin (17). Removal of this domain in addition to the di-leucine mutation does not result in further slowing of vGlut1 endocytosis (Fig. 4, B and D), but the PP2 domain demonstrates an additional role in vGlut1-regulated endocytosis of other cargos (see below, Fig. 5). To determine whether the presence of endogenous WT vGlut1 was distorting the potential impact of the di-leucine mutation, we expressed vGAA-pHluorin and vGAA-ΔPP2-pHluorin in vGlut1 KD neurons and examined endocytosis kinetics following 100-AP stimulation (Fig. 4C). These experiments showed that endocytosis kinetics of these mutant forms of vGlut1 were not influenced by the presence of WT vGlut1 (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

vGlut1 di-leucine motif rather than the second proline-rich domain (PP2) slows vGlut1 internalization and is not influenced by WT vGlut1. A, diagram showing two motifs on the C terminus of vGLUT1 where mutations were made. B, representative endocytosis kinetics for vGLUT1-pHluorin (vG-pH) and its pHluorin-tagged mutants (vGAA-pH and vGAAΔPP2-pH) plotted on a semi-log scale. C, graphics illustrate the experimental design to examine the influence of native vGlut1 when expressing mutant vGAA-pH or vGAAΔPP2-pH. D, average endocytic time constants of vG-pH (black), vGAA-pH (red), and vGAAΔPP2-pH (blue) when expressed on the WT vG background as well as those latter two when expressed in the vG KD background (pink and yellow). Significant differences were observed between vG-pH and vGAA-pH as well as vG-pH and vGAAΔPP2-pH (Student's t test), but not for vGAA-pH and vG KD + resvGAA-pH (p = 0.25, Wilcoxon rank sum test) or vGAAΔPP2-pH and vG KD + resvGAAΔPP2-pH (p = 0.25, Wilcoxon rank sum test). resVGAA refers to rescuing with an shRNA insensitive variant of the VGAA. Error bars indicate S.E.

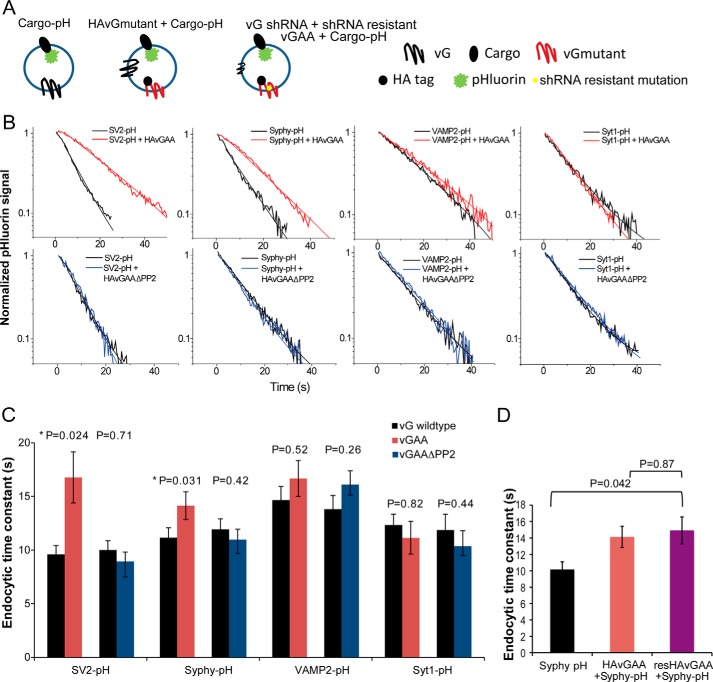

FIGURE 5.

Slow vGlut1 internalization slows internalization of other SV cargos via the PP2 domain. A, graphic illustrates the experimental design to examine the influence of mutant vG on other cargo internalization. B, representative endocytosis kinetics (thick traces) with their corresponding single exponential fits (smooth and thin traces) of various cargo proteins (black) and those from neurons co-expressed with vGAA (red) and vGAAΔPP2 (blue). C, summary of the effect of vGAA and vGAAΔPP2 on SV2, Syphy, VAMP2, and Syt1 endocytosis kinetics. Significant difference was only found for SV2 (9.6 ± 0.8 s, n = 7) when compared with SV2 co-expressing vGAA (16.8 ± 2.4 s, n = 8, p = 0.02, two-tailed Student's t test) and Syphy (10.2 ± 0.9 s, n = 7) when compared with Syphy co-expressing vGAA (14.1 ± 1.3 s, n = 7, p = 0.03, two-tailed Student's t test). D, endocytic time constants of Syphy-pHluorin when expressed alone, with HA-vGAA on the WT vG background, or with HA-vGAA (resvGAA) on the vG KD background. No difference was observed between the WT vG background and the KD background (p = 0.87, Wilcoxon rank sum test). Error bars indicate S.E.

To examine how the presence of mutant vGlut1 might impact endocytosis of other cargos, we co-expressed HA-tagged mutant vGlut1 (HA-vGAA) along with pHluorin-tagged cargo (SV) proteins and examined endocytosis kinetics of the pHluorin-tagged SV protein following 100-AP stimuli (Fig. 5A). The 100-AP exocytosis response remained unchanged in all the different combinations tested (Table 1). Interestingly, following a 100-AP stimulus, endocytosis kinetics of SV2 (16.7 ± 2.3 s, n = 8 when compared with 9.9 ± 0.8 s, n = 7; p = 0.02, Student's t test) and Syphy (14.1 ± 1.3 s, n = 8 when compared with 10.1 ± 0.9 s, n = 7; p = 0.03, Student's t test) were both slowed when co-expressed with HA-vGAA, whereas the endocytic kinetics of VAMP2 and Syt1 remained unchanged (Fig. 5, B and C). Given that removal of vGlut1 had only a modest impact on VAMP2 endocytosis, it is possible that the impact of VGAA is too subtle to detect, although it does impact this protein's endocytosis. Quantitative immunocytochemistry indicated that expression of the HA-tagged mutant led to an ∼2-fold overexpression of this protein when compared with non-transfected WT synapses, without affecting other essential endocytic proteins (data not shown); thus the ratio of WT vGlut1 when compared with vGAA is likely at most 1:1. Nonetheless this could lead to an underestimation of the true impact of vGAA on slowing other cargos. We therefore measured the kinetics of SV cargo-pH in vGlut-1 KD neurons that co-expressed shRNA-insensitive HA-vGAA (Fig. 4A). We chose Syphy-pHluorin for this experiment as the impact of VGAA was more modest on this protein than on SV2. These experiments showed that endocytosis kinetics of synaptophysin slowed by vGAA was not influenced by the presence of wild-type vG (Fig. 5D). Thus SV2 and synaptophysin appear to follow the kinetics dictated by slower vGlut1, suggesting that these proteins must interact with vGlut1 either directly or through some intermediate complex.

In addition to the di-leucine motif, vGlut1 also contains two poly-proline regions (Fig. 4A), the second of which is thought to interact with endophilin (17). Similar to previous findings (17), we found that eliminating this poly-proline domain in vGlut1 does not have any significant impact on its own endocytosis (data not shown), whereas a double mutant in vGlut1 harboring the di-leucine motif mutation and lacking the second poly-proline (vGAAΔPP2-pH) was endocytosed with similar kinetics to vGAA-pH (Fig. 4, B and C). Remarkably however, this mutant could no longer slow the kinetics of endocytosis of either SV2 or synaptophysin when co-expressed with pHluorin-tagged variants of these two SV cargos (Fig. 5, B and C). Quantitative immunocytochemistry revealed that the expression level of the double mutant was similar to that of the vGAA (not shown); thus the ability of vGlut1 to dictate the retrieval speed of other SV cargos requires its second poly-proline domain.

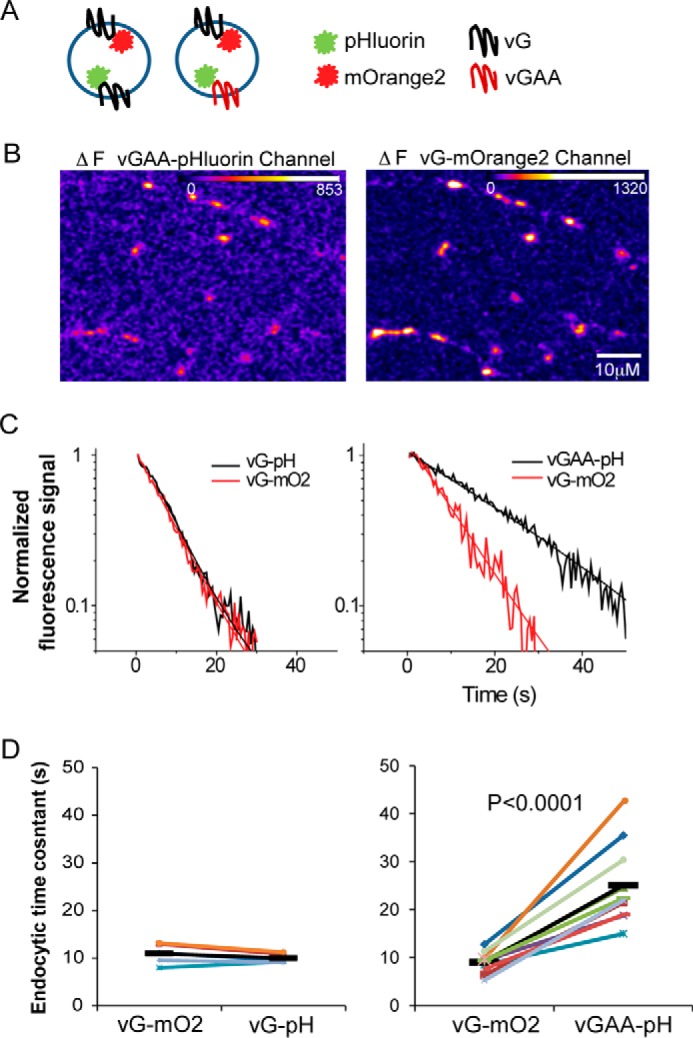

In addition to demonstrating that vGlut1 appears to dictate endocytosis kinetics of both SV2 and synaptophysin, these data also imply that there must be clear kinetic separation of cargos during SV retrieval even in the same boutons. To test this hypothesis more explicitly, we made use of mOrange2 to label vGlut1 (vG-mO2) and co-expressed it with pHluorin-tagged vGAA (Fig. 6A). mOrange2 fluorescence, like pHluorin, is quenched with protonation (pKa ∼6.5) (20) and therefore can be used in a similar fashion to pHluorin to report pH changes associated with exo-endocytosis (21) (Fig. 6B). Simultaneous monitoring of endocytosis kinetics of WT vG and vGAA (Fig. 6C) showed that these two proteins when exocytosed in the same set of boutons were internalized with differing kinetics (Fig. 6, C and D). As a control, we characterized endocytosis kinetics of two different WT vGlut1s, one labeled with mOrange2 and the other labeled with pHluorin. These experiments showed that the type of tag added to vGlut1 was not influencing the endocytosis kinetics (Fig. 6, C and D), and therefore the separation in retrieval kinetics of vGlut1 and vGAA was due to selective impairment of the di-leucine motif of vGlut1.

FIGURE 6.

Slow and fast (WT) vGlut1 internalize with different kinetics even in the same synapses. A, graphic illustrates the experimental design to examine endocytosis kinetics of two different tagged cargos simultaneously. B, difference images of the exocytic response (10 Hz, 10 s) of vG-mOrange2 and vGAA-pHluorin during simultaneous acquisition from a representative neuron expressing both proteins. C, representative endocytosis kinetics and their single exponential fits for vG-mO2 and vGAA-pH following 10-Hz, 10-s stimulus. D, summary of paired comparison (paired Student's t test) of endocytic time constants for each neuron measured in different channels.

Discussion

There are several aspects of SV endocytosis that remain very poorly understood including the nature of the initiating event, the mechanism(s) by which the SV cargo proteins are sorted and retrieved from the plasma membrane, and whether or not additional sorting occurs through an endosomal system to produce synaptic vesicles with the right stoichiometric ratios of different proteins. The data we show here demonstrate that one of the cargos that is most efficiently retrieved has a far-reaching influence on the other cargo proteins. Its absence results in slowing of at least three of the remaining five major cargo families (one of which, the V-ATPase, could not be examined), and mutations that weaken its association with endocytic machinery in turn impact the endocytosis of two other SV cargos. These data thus indicate that although not essential in initiating endocytosis, vGlut1, in addition to its role in controlling neurotransmitter filling of vesicles (22, 23), plays a key role in coordinating the retrieval of multiple cargos. Among the four SV proteins we examined, vGlut1 had the strongest influence on SV2 followed by Syphy, as their endocytosis was slowed either by vGlut1 removal or by introducing a slowly endocytosing variant of vGlut1. All but one (Syt1) SV cargo protein were impacted by removal of vGlut1. Remarkably, both SV2 and Syphy are still retrieved much faster (∼15 s) than vGAA itself (∼25 s). The influence of the slow vGlut1 does not appear to be impacted by the presence of WT vGlut1 (Fig. 5D); thus other regulatory mechanisms must be present to counteract the slowed kinetics offered by vGAA.

One of the SV cargos, Syt1, was particularly insensitive to perturbations in vGlut1. Given its critical calcium-sensing role for both exocytosis and endocytosis, it has been suggested to act as a “hub” integrating membrane fusion and cargo retrieval (24). Its insensitivity to the presence of vGlut1 suggests that Syt1 and vGlut1 may be acting in parallel upstream in endocytic sorting of SV cargos given that Syt1 has also been implicated in controlling synaptophysin endocytosis (25, 26). It is possible that Syt1 is upstream of vGlut1 in the hierarchy of SV cargo control. Alternatively, vGlut1 and Syt1 may represent redundant cargo-driven pathways in controlling SV cargo endocytosis. The decision of which cargo-driven pathway a particular SV protein follows appears to be strongly influenced by specific interactions with the endocytic machinery. Removal of the second poly-proline stretch of vGlut1 prevented slowly endocytosing vGlut1 from influencing the retrieval kinetics of other cargos; thus this domain seems critical in determining whether SV cargos potentially follow vGlut or Syt. A previous study reported that stonin 2 had even greater influence than AP-2 on the endocytosis of numerous SV cargos (26). However, the impact of AP-2 removal in that work was much smaller than observed previously by our group (3), conceivably because the siRNAs chosen for ablation were less efficient than the shRNA used in (3). It is possible, however, that stonin 2 and AP-2 represent parallel partially redundant pathways for endocytosis for the full collection of SV cargos.

However, the demonstration that different cargos can be retrieved at the same terminals with significantly different kinetics suggests that different cargos are not equally sorted at the plasma membrane into the vesicles that bud from the plasma membrane, arguing that an additional endosomal sorting step(s) is(are) likely occurring. Such endocytic sorting for SVs has been suggested in recent high-pressure freeze experiments (27). The picture that emerges regarding endocytosis at synapses is considerably different from that for classical clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Instead of individual cargo molecules determining their own endocytic fate, at nerve terminals, multiple cargos likely collectively control endocytosis.

Author Contributions

P. Y. P and T. A. R. designed the experiments. J. M. performed cell culture and some immunostaining experiments. P. Y. P and T. A. R. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yogesh Gera for outstanding technical support and Reinhard Jahn for the generous gift of the anti-synaptophysin antibody and Ed Chapman for the gift of SV2-pHluorin.

This work was supported by NINDS, National Institutes of Health Grant NS036942 (to T. A. R.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- SV

- synaptic vesicle

- vGlut

- vesicular glutamate transporter

- Syphy

- synaptophysin

- Syt

- synaptotagmin

- VAMP

- vesicle-associated membrane protein

- AP

- action potential

- pH

- pHluorin

- vG

- vGlut1

- KD

- knockdown

- PP2

- poly-proline domain 2.

References

- 1. Raimondi A., Ferguson S. M., Lou X., Armbruster M., Paradise S., Giovedi S., Messa M., Kono N., Takasaki J., Cappello V., O'Toole E., Ryan T. A., De Camilli P. (2011) Overlapping role of dynamin isoforms in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Neuron 70, 1100–1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Granseth B., Odermatt B., Royle S. J., Lagnado L. (2006) Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is the dominant mechanism of vesicle retrieval at hippocampal synapses. Neuron 51, 773–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim S. H., Ryan T. A. (2009) Synaptic vesicle recycling at CNS synapses without AP-2. J. Neurosci. 29, 3865–3874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Robinson M. S. (2004) Adaptable adaptors for coated vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 167–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fernández-Alfonso T., Kwan R., Ryan T. A. (2006) Synaptic vesicles interchange their membrane proteins with a large surface reservoir during recycling. Neuron 51, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wienisch M., Klingauf J. (2006) Vesicular proteins exocytosed and subsequently retrieved by compensatory endocytosis are nonidentical. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1019–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dittman J., Ryan T. A. (2009) Molecular circuitry of endocytosis at nerve terminals. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 25, 133–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haucke V., Neher E., Sigrist S. J. (2011) Protein scaffolds in the coupling of synaptic exocytosis and endocytosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 127–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kwon S. E., Chapman E. R. (2011) Synaptophysin regulates the kinetics of synaptic vesicle endocytosis in central neurons. Neuron 70, 847–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gordon S. L., Leube R. E., Cousin M. A. (2011) Synaptophysin is required for synaptobrevin retrieval during synaptic vesicle endocytosis. J. Neurosci. 31, 14032–14036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takamori S., Holt M., Stenius K., Lemke E. A., Grønborg M., Riedel D., Urlaub H., Schenck S., Brügger B., Ringler P., Müller S. A., Rammner B., Gräter F., Hub J. S., De Groot B. L., Mieskes G., Moriyama Y., Klingauf J., Grubmüller H., Heuser J., Wieland F., Jahn R. (2006) Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell 127, 831–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Balaji J., Ryan T. A. (2007) Single-vesicle imaging reveals that synaptic vesicle exocytosis and endocytosis are coupled by a single stochastic mode. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 20576–20581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Armbruster M., Ryan T. A. (2011) Synaptic vesicle retrieval time is a cell-wide rather than individual-synapse property. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 824–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Armbruster M., Messa M., Ferguson S. M., De Camilli P., Ryan T. A. (2013) Dynamin phosphorylation controls optimization of endocytosis for brief action potential bursts. ELife 2, e00845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ryan T. A. (1999) Inhibitors of myosin light chain kinase block synaptic vesicle pool mobilization during action potential firing. J. Neurosci. 19, 1317–1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferguson S. M., Brasnjo G., Hayashi M., Wölfel M., Collesi C., Giovedi S., Raimondi A., Gong L. W., Ariel P., Paradise S., O'Toole E., Flavell R., Cremona O., Miesenböck G., Ryan T. A., De Camilli P. (2007) A selective activity-dependent requirement for dynamin 1 in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Science 316, 570–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Voglmaier S. M., Kam K., Yang H., Fortin D. L., Hua Z., Nicoll R. A., Edwards R. H. (2006) Distinct endocytic pathways control the rate and extent of synaptic vesicle protein recycling. Neuron 51, 71–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kelly B. T., McCoy A. J., Späte K., Miller S. E., Evans P. R., Höning S., Owen D. J. (2008) A structural explanation for the binding of endocytic dileucine motifs by the AP2 complex. Nature 456, 976–979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim S. H., Ryan T. A. (2009) A distributed set of interactions controls μ2 functionality in the role of AP-2 as a sorting adaptor in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 32803–32812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shaner N. C., Lin M. Z., McKeown M. R., Steinbach P. A., Hazelwood K. L., Davidson M. W., Tsien R. Y. (2008) Improving the photostability of bright monomeric orange and red fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods 5, 545–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sankaranarayanan S., De Angelis D., Rothman J. E., Ryan T. A. (2000) The use of pHluorins for optical measurements of presynaptic activity. Biophys. J. 79, 2199–2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fremeau R. T. Jr., Kam K., Qureshi T., Johnson J., Copenhagen D. R., Storm-Mathisen J., Chaudhry F. A., Nicoll R. A., Edwards R. H. (2004) Vesicular glutamate transporters 1 and 2 target to functionally distinct synaptic release sites. Science 304, 1815–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wojcik S. M., Rhee J. S., Herzog E., Sigler A., Jahn R., Takamori S., Brose N., Rosenmund C. (2004) An essential role for vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT1) in postnatal development and control of quantal size. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 7158–7163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koch M., Holt M. (2012) Coupling exo- and endocytosis: an essential role for PIP2 at the synapse. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1821, 1114–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yao J., Nowack A., Kensel-Hammes P., Gardner R. G., Bajjalieh S. M. (2010) Cotrafficking of SV2 and synaptotagmin at the synapse. J. Neurosci. 30, 5569–5578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Willox A. K., Royle S. J. (2012) Stonin 2 is a major adaptor protein for clathrin-mediated synaptic vesicle retrieval. Curr. Biol. 22, 1435–1439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Watanabe S., Trimbuch T., Camacho-Pérez M., Rost B. R., Brokowski B., Söhl-Kielczynski B., Felies A., Davis M. W., Rosenmund C., Jorgensen E. M. (2014) Clathrin regenerates synaptic vesicles from endosomes. Nature 515, 228–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]