Abstract

Stem cells generate the differentiated progeny cells of adult tissues. Stem cells in the Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodite germline are maintained within a proliferative zone of ∼230 cells, ∼20 cell diameters in length, through GLP-1 Notch signaling. The distal tip cell caps the germline and supplies GLP-1-activating ligand, and the distal-most germ cells that occupy this niche are likely self-renewing stem cells with active GLP-1 signaling. As germ cells are displaced from the niche, GLP-1 activity likely decreases, yet mitotically cycling germ cells are found throughout the proliferative zone prior to overt meiotic differentiation. Following loss of GLP-1 activity, it remains unclear whether stem cells undergo transit-amplifying (TA) divisions or more directly enter meiosis. To distinguish between these possibilities we employed a temperature-sensitive (ts) glp-1 mutant to manipulate GLP-1 activity. We characterized proliferative zone dynamics in glp-1(ts) mutants at permissive temperature and then analyzed the kinetics of meiotic entry of proliferative zone cells after loss of GLP-1. We found that entry of proliferative zone cells into meiosis following loss of GLP-1 activity is largely synchronous and independent of their distal-proximal position. Furthermore, the majority of cells complete only a single mitotic division before entering meiosis, independent of their distal-proximal position. We conclude that germ cells do not undergo TA divisions following loss of GLP-1 activity. We present a model for the dynamics of the proliferative zone that utilizes cell cycle rate and proliferative zone size and output and incorporates the more direct meiotic differentiation of germ cells following loss of GLP-1 activity.

Keywords: stem cells, germline, Caenorhabditis elegans, GLP-1 Notch, meiosis, differentiation, proliferation

IN polarized adult tissues, differentiated progeny cell types are produced by renewable stem cell systems. Variations in the demand for differentiated cells, for example, based on species-specific requirements, lead to differences in stem cell systems including features such as the stem cell population size, quiescence, cell cycle rate, and the extent of utilization of transit-amplifying (TA) cells. Understanding the regulation of stem cell systems requires a synthesis of these features.

The Caenorhabditis elegans germline is an important model for the study of stem cell biology (Kimble 2011; Hansen and Schedl 2013; Hubbard et al. 2013). The adult hermaphrodite germline contains stem cells based on their ability to produce gametes over an extended portion of life span (∼10 days) (Hughes et al. 2007), their ability to regenerate the adult germline following environmental perturbation (Angelo and Van Gilst 2009; Seidel and Kimble 2011), and their multipotency (being able to generate either female or male gametes) (Ellis and Schedl 2007). The germline is a polarized tube-shaped tissue that is an assembly line designed for the rapid production of gametes under optimal growth conditions. The stem cells reside at the distal end of the germline within a large population of ∼230 stem/progenitor cells covering an ∼20-cell diameter region called the proliferative zone (PZ) or mitotic zone (Figure 1A), as M-phase cells can be observed throughout the region (Hansen et al. 2004a; Crittenden et al. 2006). Just proximal to the PZ is the meiotic entry region where germ cells undergo overt differentiation including assembly of the meiotic chromosome axes and homolog pairing associated with the leptotene/zygotene stage of meiotic prophase (Lui and Colaiacovo 2013); thus antibody markers allow PZ cells (nuclei that are REC-8 positive/HIM-3 negative under mild fixation conditions) to be easily distinguished from early meiotic prophase cells (REC-8 negative/HIM-3 positive) (Hansen et al. 2004b; Fox et al. 2011). The distal germline is capped by the large somatic distal tip cell (DTC) that functions as the niche to promote the stem cell fate and/or inhibit the meiotic fate; laser ablation of the DTC results in all PZ cells entering meiosis (Kimble and White 1981). This finding has led to the model that as PZ stem cells move proximally they escape the influence of the DTC and switch to meiotic development. Differentiation in some stem cell systems is associated with asymmetric stem cell divisions and stereotypic TA divisions (Spradling et al. 2011). However, analysis of the PZ in C. elegans in fixed germlines has failed to detect asymmetric divisions or stereotypic patterns of synchronous cell divisions (Crittenden et al. 2006).

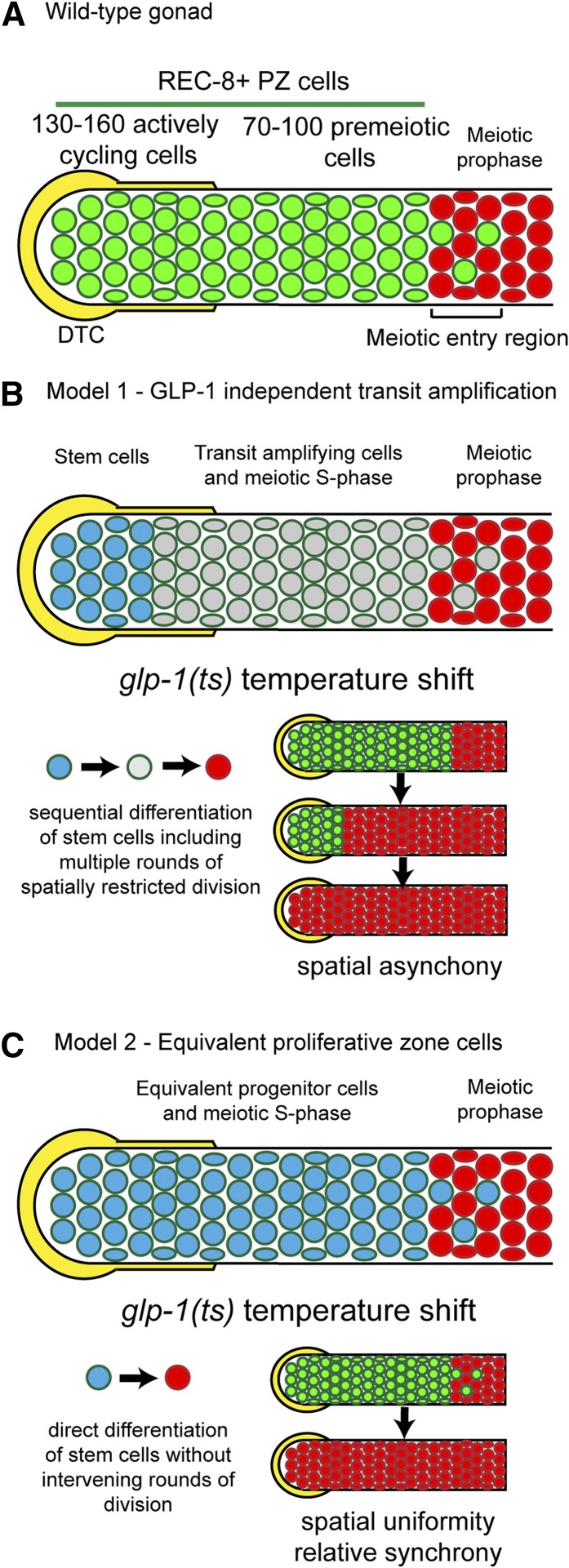

Figure 1.

Alternative models for organization of the proliferative zone. (A) The germline PZ is capped by the somatic DTC (yellow) niche and contains ∼230 REC-8-positive, HIM-3-negative PZ cells (green). This includes 130–160 mitotically cycling cells and 70–100 premeiotic cells (largely undergoing meiotic S-phase). We refer to all REC-8-positive cells as PZ cells. In the meiotic entry region, both PZ cells and meiotic prophase HIM-3 positive; REC-8 negative cells (red) are observed, which are followed more proximally by cells that are all in meiotic prophase. (B) One model of PZ dynamics proposes that there are distal GLP-1-signaling-dependent stem cells (blue) followed more proximally by GLP-1-signaling-independent transit amplification (gray); as daughters of the stem cells move proximally, GLP-1 signaling falls, germ cells switch to transit amplification undergoing multiple rounds of mitotic division, and progress toward meiotic differentiation. This model predicts that shifting glp-1(ts) mutant hermaphrodites to the restrictive temperature (resulting in rapid loss of GLP-1 activity throughout the PZ) would lead to a proximal-to-distal wave of induced meiotic entry, reflecting developmental differences between the distal stem cells and the proximal TA cells with respect to maturation toward meiosis. Furthermore, the model predicts that the final rounds of mitosis would be spatially restricted to the distal-most region where the stem cells had been converted to TA divisions as a consequence of the temperature shift. (C) An alternative model is that the DTC niche is large, resulting in a large stem cell pool where germ cells do not undergo GLP-1-independent transit amplification, but instead more immediately enter meiosis. This model implies that PZ cells are developmentally equivalent in terms of GLP-1 activity and maturation toward meiosis (indicated by blue color throughout). Experimentally, rapid loss of GLP-1 activity following the temperature shift is predicted to result in roughly synchronized meiotic entry, reflecting developmental equivalency. In addition, the transition from PZ cell to meiosis would not involve multiple rounds of intervening mitoses, and any cell divisions that occurred would be randomly distributed.

Lineage analysis and cell transplantations are important approaches for understanding cell fate and cellular dynamics in a number of stem cell systems but unfortunately are not currently feasible for the C. elegans germline. Instead, dynamic cellular behavior in the wild-type young adult distal germline has been deduced from cell-population-based studies employing the incorporation of cytologically detectable nucleotides [e.g., BrdU/ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU)] (Crittenden et al. 2006; Jaramillo-Lambert et al. 2007; Fox et al. 2011). These studies showed that mitotic PZ cells cycle continuously (quiescence is not observed) (Crittenden et al. 2006) and have a rapid cell cycle with a short or no G1 phase (Fox et al. 2011), that germ cells move from distal to proximal at ∼1 cell diameter/hour (Crittenden et al. 2006; Jaramillo-Lambert et al. 2007), and that ∼20 cells enter meiosis/hour (termed “proliferative zone output”) (Fox et al. 2011). The proximal region of the PZ was found to contain cells that were in meiotic S-phase (e.g., S-phase cells that do not undergo an M-phase prior to becoming HIM-3 positive) (Jaramillo-Lambert et al. 2007; Fox et al. 2011). Since the proximal region of the PZ also contains M-phase cells (Hansen et al. 2004a; Crittenden et al. 2006), this region is a mixture of mitotically cycling cells and meiotic S-phase cells. Employing measures of cell cycle length and proliferative zone output allows estimates of the fraction of the PZ cells that are mitotically cycling vs. undergoing meiotic S-phase; these measures indicate that 130–160 PZ cells (of 230 total) are mitotically cycling and the remaining 70–100 cells, which have completed mitosis but have not yet initiated meiotic prophase, largely account for meiotic S-phase (see Figure 1A) (Fox et al. 2011). These studies provide a basis for investigating the relationship between proliferative zone dynamics and the underlying signaling pathways that regulate the fate of cells within the proliferative zone. However, an important question remains whether all of the mitotically cycling PZ cells are developmentally equivalent.

Proliferative cell fate in the germline relies on activated GLP-1 Notch signaling (Austin and Kimble 1987). The somatic DTC expresses the GLP-1 ligands LAG-2 and APX-1 and activates the GLP-1 receptor in PZ germ cells (Crittenden et al. 1994; Henderson et al. 1994; Nadarajan et al. 2009). The DTC caps the distal-most ∼3–4 cell diameters and has extensive contact through intercalating cellular processes in a region known as the DTC plexus that extends 8–9 cell diameters from the distal tip (Byrd et al. 2014). Active GLP-1 promotes the proliferative fate by repressing the GLD-1 and GLD-2 meiotic entry pathways (Francis et al. 1995; Kadyk and Kimble 1998; Eckmann et al. 2004; Hansen et al. 2004a). These pathways appear to regulate meiotic entry through translational regulation of a battery of genes. GLD-1 binds and represses the translation of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs), presumably repressing genes that promote the proliferative fate (Lee and Schedl 2001; Fox et al. 2011). Conversely, the GLD-2 pathway is thought to activate the translation of genes that promote meiosis (Kadyk and Kimble 1998; Wang et al. 2002).

In a number of stem cell systems, the bulk of cell proliferation occurs within TA cells that execute a finite number of programmed divisions (Spradling et al. 2011; Valli et al. 2015). This may allow the activity of a relatively small number of stem cells to be amplified in a controlled manner to generate the appropriate number of differentiated progeny cells and thus prevent stem cell exhaustion. In the Drosophila ovary, germline stem cells generate cystoblasts that undergo four rounds of TA mitotic divisions with incomplete cytokinesis prior to meiotic differentiation. Maintenance of germline stem cell self-renewal is mediated primarily by BMP signaling between the somatic cap niche cell and the stem cells (Xie and Spradling 1998; Chen and McKearin 2003). The switch from germline stem cells to TA cells occurs when germ cells are displaced from the niche and the BMP signal falls below a threshold necessary for the stem cell fate (Chen et al. 2011). Significantly, the cystoblast fate and TA divisions do not require BMP signaling (Xie and Spradling 1998). Analogously, in the mouse testis, PLZF (ZBTB16) is required for spermatogonial stem cell function but is not necessary for transit amplification (Buaas et al. 2004) while LIN28 displays the converse activity, being required for TA but not necessary for spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal (Chakraborty et al. 2014). Thus germline stem cell self-renewal and transit amplification are independently regulated and TA cells undergo multiple rounds of cell division, which is often a fixed number depending on the system.

The consensus view for the C. elegans germline is that the DTC maintains the stem cell/proliferative cell fate through GLP-1 signaling and that as cells are displaced/move proximally, and escape the influence of DTC - GLP-1 signaling, progenitor cells progress toward initiation of meiotic development and gametogenesis. Important questions are the following: (1) How many cells in the proliferative zone are stem cells? (2) Do the progenitors undergo progression to meiotic differentiation through transit-amplifying divisions, or do they enter meiotic prophase directly from the stem cell fate? Work from Cinquin et al. suggests that the proliferative zone of the adult hermaphrodite contains at least two distinct populations of cells: a distal pool of ∼35–70 stem cells and a proximal pool of ∼150 differentiated, likely transit-amplifying cells (Cinquin et al. 2010). This hypothesis was supported by the observation that distal vs. proximal cell populations show distinct responses to two forms of experimental manipulation: cell cycle arrest and induced meiotic entry through loss of GLP-1 signaling. When mitotic cell cycle progression was blocked, proximal but not distal PZ cells entered meiosis, and when meiotic entry was experimentally induced, proximal PZ cells displayed signs of meiotic differentiation earlier (Cinquin et al. 2010). These results were used to provide support for a model that a proximal pool of cells within the PZ has differentiated from the stem cell state and therefore represents a pool of TA cells (see Figure 1B, model 1: GLP-1 independent transit amplification). Nonetheless, the extent of GLP-1 activity within the proliferative zone and whether TA divisions occur after loss of GLP-1 activity remain unknown. Furthermore, the DTC plexus is large, displaying intimate contact with germ cells up to 8–9 cell diameters from the distal tip (Byrd et al. 2014). Thus, an alternative model is that the stem cell population is large and that all mitotically cycling cells in the PZ are dependent on GLP-1 signaling (see Figure 1C, model 2: Equivalent proliferative zone cells) (Hansen and Schedl 2013).

The two above models make distinct predictions for how PZ cells would respond to experimentally manipulated loss of GLP-1 activity using a glp-1 temperature sensitive (ts) mutant in terms of (1) the spatial and temporal pattern of meiotic differentiation of the PZ cells and subsequent cell divisions and (2) the extent of mitotic proliferation prior to entry into meiosis (Figure 1, B and C). If there is GLP-1-dependent stem cell self-renewal followed by GLP-1 independent transit amplification (model 1), loss of GLP-1 activity should lead to (1) a proximal to distal wave of differentiation that reflects the initial underlying developmental status of PZ cells (distal germ cells would be less mature germline stem cells and differentiate last whereas proximal cells would be progressively more mature TA cells and differentiate first) and (2) multiple rounds of mitotic division among the distal-most germ cells following glp-1(ts) temperature-shift-induced conversion of the stem cells into TA cells (Figure 1B, see also Cinquin et al. 2010). Alternatively, if the stem cell population is large and GLP-1-independent TA divisions are not present (model 2), we expect that loss of GLP-1 activity should lead to (1) relatively synchronized and spatially uniform meiotic entry throughout the proliferative zone and (2) limited mitotic division prior to meiotic differentiation that is not spatially restricted (Figure 1C). To test these predictions, we used the glp-1(bn18) ts mutant to manipulate glp-1 activity, REC-8 and HIM-3 as molecular markers to determine the developmental status of individual germ cells, and a variety of phospho-Histone 3-Ser10 (pH3, an M-phase marker) and EdU-based assays to examine cell cycle behavior. To better understand steady-state dynamics, we provide estimates for cell cycle length and structure, meiotic entry kinetics (proliferative zone output), and the total number of mitotically cycling PZ cells vs. those undergoing meiotic S-phase in glp-1(bn18) at permissive temperature. Ultimately, we show that, after loss of GLP-1 activity, PZ cells (1) progress to meiotic prophase relatively synchronously with spatial uniformity and (2) that most PZ cells complete a single mitotic division prior to meiotic differentiation. Based on these observations, we conclude that the PZ contains a large stem cell population that does not undergo GLP-1-independent TA divisions prior to differentiation. Taking into account our estimates for the number of mitotically cycling cells, their proliferation rate, and the PZ output, we present a model of proliferative zone dynamics that accounts for the absence of GLP-1-independent transit amplification.

Materials and Methods

Nematode maintenance and strains

Animals were propagated at 15° under standard conditions. The following strains were used: wild type (N2 Bristol), glp-1(bn18), glp-1(e2141), glp-1(q224), gld-1(q485); glp-1(bn18), gld-2(q497); glp-1(bn18), gld-3(q730); glp-1(bn18), nos-3(oz231); glp-1(bn18), and fbf-2(q738); glp-1(bn18). These alleles are described on the WormBase web site (https://www.wormbase.org), where gld-1, gld-2, gld-3, nos-3, and fbf-2 mutations are likely null.

Temperature shift and EdU labeling

For all temperature-shift experiments, animals grown at 15° were synchronized to 24 hr past L4 and then shifted to plates pre-incubated at 25°. Animals were transferred by pick, ∼50 animals at a time, with the entire transfer process typically lasting <3 min. Plates with EdU-labeled bacteria were prepared as described (Fox et al. 2011). Pulse-chase experiments were performed as previously described under conditions where the chase was effective in eliminating new EdU labeling (Fox et al. 2011).

Immunohistochemistry and microscopy

Germlines were dissected and processed as described previously (Jones et al. 1996). The following antibodies were used: rat anti-REC-8 (1:100) from Joseph Loidl (University of Vienna); rabbit anti-HIM-3 (1:100) from Monique Zetka (McGill University); rabbit anti-phospho-(Ser10)-Histone 3 (pH3) (1:400) from Upstate. EdU labeling was performed using a kit (Life Technologies) as described (Fox et al. 2011). Germlines were stained with 4′,6-dianmidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma). Secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) were diluted 1:500. Germlines were imaged with a PerkinElmer spinning disk confocal microscope, and images were processed with Adobe Photoshop. Confocal stacks were analyzed using Volocity software. Cells were manually counted using a cell counter tool. For scoring individual nuclei, EdU, REC-8, or HIM-3 were assayed in multiple focal planes.

Calculation of cell cycle length, proliferative zone output, and number of mitotically cycling cells

Since mitotic cycling in the proliferative zone is continuous (no quiescent cells) (Crittenden et al. 2006; Fox et al. 2011), the relative length of individual phases of the cell cycle can be determined by their frequency among PZ cells. The mitotic index (number of pH3-positive nuclei/number of REC-8-positive nuclei) provides the relative length of M-phase and the S-phase index (number of EdU-positive nuclei in a 30-min pulse/total number of REC-8-positive nuclei) provides the relative length of S-phase. As we have previously provided evidence that G1 phase is either very short or nonexistent in the adult hermaphrodite germline (Fox et al. 2011), we assume that the remaining pH3/EdU-negative cells are in G2. Two methods were used to calculate cell cycle length. First, the length of G2+M+G1 is determined by the minimum EdU pulse required to label all PZ cells (Crittenden et al. 2006). The total cell cycle length is then extrapolated from the length of G2+M+G1 based on its relative length to the total cell cycle, which is determined by the percentage of cells that remain unlabeled after a 30-min EdU pulse. Since the assay to determine G2+M+G1 is limited by the slowest cycling cells, this method likely describes the maximum length of the cell cycle. The second method is based on extrapolating the total cell cycle from the length of G2 (Fox et al. 2011). The length of G2 was determined according to the time by which EdU-labeled cells reach M-phase. Since M-phase cells can be scored on an individual basis, this assay provides a distribution of values. Therefore, we can extrapolate the total cell cycle length from the median length of G2 (time when 50% of M-phase cells are EdU-positive after administering a continuous pulse). Proliferative zone output was determined by counting the number of EdU-labeled nuclei that enter meiosis (HIM-3 positive, REC-8 negative) after 10 hr of EdU feeding. Under the assumption that at steady state each mitotic division is balanced by a cell entering meiosis, the output of the proliferative zone should equal the number of mitotically dividing cells multiplied by their division rate (Fox et al. 2011). Therefore, to solve for the number of mitotically dividing cells, we divided the output (cells/hour) by the division rate (divisions/hour).

Results

GLP-1 regulates the size of the proliferation zone

To investigate how PZ cells in the adult hermaphrodite respond to loss of GLP-1, we used the temperature-sensitive loss-of-function mutant glp-1(bn18) (Kodoyianni et al. 1992) to manipulate GLP-1 activity. First, we addressed whether glp-1(bn18) mutants at the permissive temperature (15°) are comparable to wild type in terms of cell cycle and meiotic entry kinetics. Previous work has characterized several important aspects of the proliferative zone in wild-type germlines at 20°: (1) the proliferative zone contains ∼230 cells and extends ∼20 cell diameters, (2) the DTC fails to contact most cells beyond the distal-most 8–9 cell diameters, (3) 60–70% of the proliferative zone is actively mitotically cycling (quiescence is absent), and (4) the remaining 30–40% of the PZ cells have switched from the mitotic cell cycle to meiotic S-phase but have not begun overt meiotic differentiation (Fox et al. 2011). glp-1(ts) mutants at the permissive temperature have been widely used as sensitized backgrounds to identify or test for genes acting in Notch signaling and/or promoting the proliferative fate (Qiao et al. 1995; Hansen et al. 2004b; Korta et al. 2012). Thus we predicted that GLP-1 activity in glp-1(bn18) mutants at the permissive temperature is reduced compared to wild type, causing a decrease in proliferative zone size. Using REC-8 and HIM-3 antibodies to distinguish PZ cells vs. cells in meiotic prophase (Hansen et al. 2004a), we found that glp-1(bn18) mutants indeed have fewer PZ cells at permissive temperature (15°) and that the size of the proliferative zone in glp-1(bn18) varies inversely with temperature (Figure 2, A–C, and Table 1).

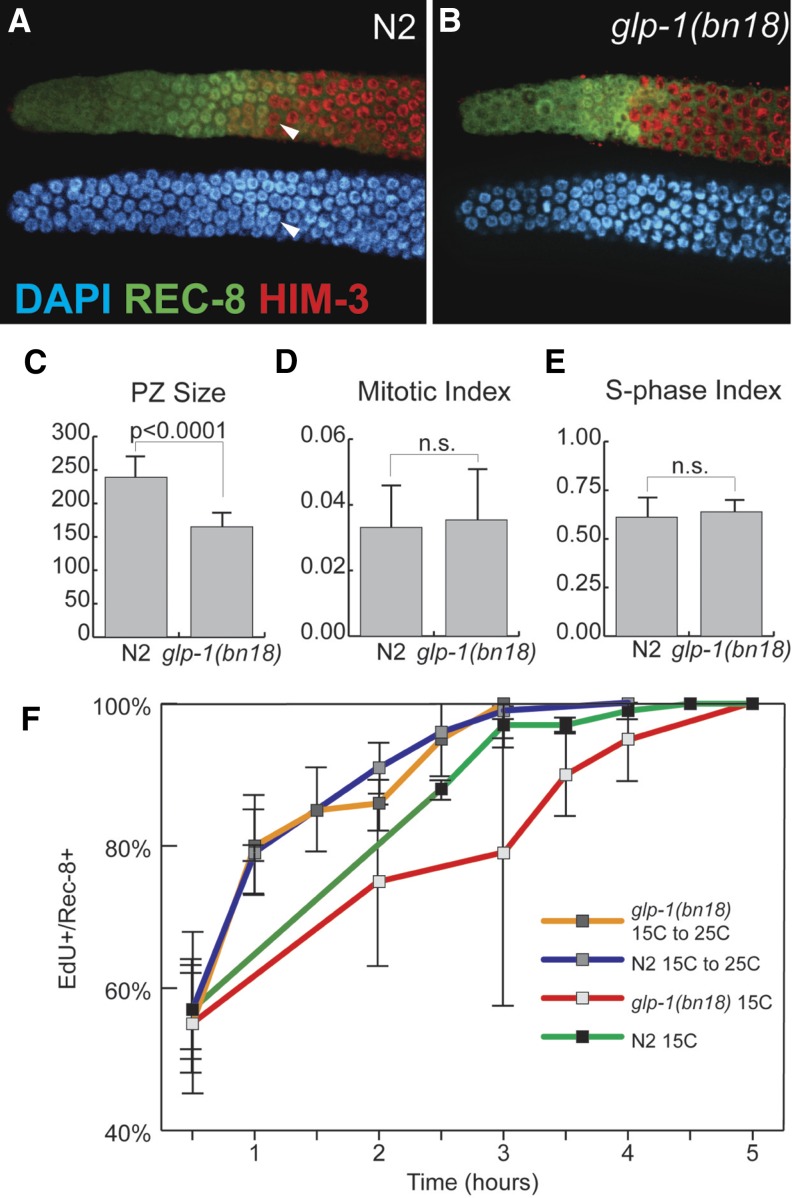

Figure 2.

GLP-1 does not affect cell cycle kinetics. Proliferative zone of wild-type N2 (A) and glp-1(bn18) (B) germlines stained with DAPI (blue), REC-8 antibody (green), and HIM-3 antibody (red). Arrowheads in A indicate an early meiotic prophase cell (top, red) based on HIM-3-positive, REC-8-negative staining with homogenous DAPI staining (bottom, blue) that does not display a crescent-shaped DAPI morphology. Proliferative zone size (C) was determined by counting REC-8-positive nuclei. Mitotic index (D) was calculated by normalizing the number of pH3-positive nuclei to the number of PZ cells. S-phase index was calculated by normalizing the number of EdU-positive nuclei (following a 30-min pulse) to the number of PZ cells. The graph in F plots the percentage of PZ cells that are EdU positive vs. length of EdU feeding. The length of G2+M+G1 corresponds to the time after which all PZ cells incorporate EdU. All experiments, except where indicated, were performed at 15°, permissive temperature for the glp-1(bn18) mutant. (C) N2, n = 18 germlines; glp-1(bn18), n = 20. (D) N2, n = 49; glp-1(bn18), n = 54. (E) N2, n = 18; glp-1(bn18), n = 20. (F) For all time points, at least eight germlines were scored. All experiments performed at 15°. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Table 1. Proliferative zone size.

| Genotype | Temperature (°C) | PZ size (cells)a | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 15 | 235 ± 19 | 8 |

| 20 | 232 ± 23 | 7 | |

| 25 | 214 ± 12 | 7 | |

| glp-1(bn18) | 15 | 165 ± 26 | 26 |

| 20 | 116 ± 9 | 12 | |

| 22 | 84 ± 13 | 10 | |

| glp-1(e2141) | 15 | 144 ± 16 | 20 |

| 20 | 103 ± 7 | 10 | |

| glp-1(q224) | 15 | 110 ± 11 | 10 |

| glp-1(bn18); nos-3(oz231) | 15 | 149 ± 29 | 10 |

| glp-1(bn18); gld-1(q485) | 15 | 106 ± 7 | 8 |

| glp-1(bn18); gld-2(q497) | 15 | 339 ± 30 | 8 |

| glp-1(bn18); gld-3(q730) | 15 | 243 ± 21 | 8 |

| glp-1(bn18); fbf-2(q738) | 15 | 198 ± 28 | 10 |

PZ size was determined by counting REC-8-positive cells 24 hr past L4.

We next analyzed cell cycle progression in glp-1(bn18) mutants. Using pH3 antibody and EdU incorporation for cell cycle analysis, we found that both M-phase and S-phase indices are equivalent in glp-1(bn18) and wild type at 15° and 20° (Figure 2, D and E). We next measured the length of G2+M+G1 using an assay in which we determined the shortest continuous EdU pulse required to label all PZ cells (Crittenden et al. 2006; Fox et al. 2011). In both wild-type and glp-1(bn18) animals at 15°, we found that a 4.5- to 5-hr EdU pulse was sufficient to label all PZ cells (Figure 2F), thus indicating that the maximum length of time between subsequent S-phases (G2+M+G1) is ∼5 hr. Similarly, ∼3 hr was determined for the median length of G2 alone for both wild-type and glp-1(bn18) animals (Supporting Information, Figure S1), which extrapolates to a cell cycle time of ∼9 hr (see Materials and Methods). Based on this analysis of wild-type and glp-1(bn18) mutants at 15° we deduce the following: (1) PZ cells do not enter quiescence and (2) the length of the cell cycle is ∼9–12 hr (see Materials and Methods). Finally, we determined the output of the proliferative zone, which subsequently allows us to calculate how many PZ cells are mitotically cycling vs. premeiotic (Table 2). We find that in glp-1(bn18) at 15°, 107 ± 19 cells enter meiosis over a 10-hr period, corresponding to an output of 10.7 cells/hour. For wild-type germlines, we observe that 154 ± 31 cells enter meiosis over a 10-hr period (15.4 cells/hour). The output of the proliferative zone suggests that in both glp-1(bn18) and wild type, 60–80% of the PZ cells are mitotically cycling (97–128 of ∼165 in glp-1(bn18) vs. 139–185 of ∼230 in wild type). Since mitotic cell cycle progression is continuous, we conclude that the remaining 20–40% of the PZ cells (35–67 in glp-1(bn18) vs. 45–90 in wild type) are in meiotic S-phase. Based on the above results (summarized in Table 3), we conclude that reduced GLP-1 activity in glp-1(bn18) at permissive temperature affects the size of the proliferative zone but does not affect mitotic cell cycle kinetics.

Table 2. Proliferative zone output.

| Genotype | 10-hr outputa | Actively cycling populationb |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 154 ± 31 (n = 9) | 140–185 |

| glp-1(bn18) | 107 ± 19 (n = 11) | 100–128 |

| glp-1(bn18); gld-2(q497) | 133 ± 28 (n = 9) | 117–156 |

| glp-1(bn18); gld-3(q730) | 42 ± 14 (n = 10) | Unknownc |

The 10-hr output was obtained by counting the number of EdU-positive, HIM-3-positive nuclei per gonad after 10 hr of EdU feeding.

Actively cycling population was calculated by dividing the output (cells/hr) by the division rate (divisions/hr) (see Materials and Methods).

The size of the actively cycling population in glp-1(bn18); gld-3(q730) is not available since the division rate has not been determined.

Table 3. Mitotic cell cycle summary (15°).

| Wild type | glp-1(bn18) | |

|---|---|---|

| Proliferative cells | 240 ± 27, n = 18 | 166 ± 19, n = 20 |

| S-phase index | 63 ± 8%, n = 18 | 59 ± 7%, n = 20 |

| M-phase index | 3 ± 1%, n = 49 | 3 ± 1%, n = 54 |

| Maximum length of G2+M+G1 | 4.5 hr | 5 hr |

| Maximum length of G2+M+G1 (15°–25° shift) | 3 hr | 3 hr |

| Maximum length of G2 | 4.5 hr | 5 hr |

| Median length of G2 | 3 hr | 3 hr |

| Extrapolated cell cycle length (based on G2+M+G1) | 12 hr | 12 hr |

| Extrapolated cell cycle length (based on G2) | 9 hr | 9 hr |

Cells throughout the proliferative zone rapidly and synchronously respond to loss of GLP-1 activity

To begin testing the two models of proliferative zone regulation, we next analyzed meiotic entry kinetics in glp-1(bn18) after shift to restrictive temperature (Figure 1) (Cinquin et al. 2010). As discussed above, if the PZ contains GLP-1-signaling dependent stem cells in the distal region followed by GLP-1-independent TA divisions in the proximal region of the proliferative zone, induced loss of GLP-1 activity would lead to a proximal-to-distal wave of meiotic entry (Figure 1B). This wave model is based on the assumption that proximally located TA cells would have matured beyond the status of the distally located stem cells and that their earlier meiotic differentiation would reflect their advanced developmental progression. If the PZ contains a large pool of stem cells and lacks GLP-1-independent TA divisions, we predict that induced loss of GLP-1 activity should cause a roughly synchronized progression of PZ cells to meiosis regardless of their distal-proximal location (Figure 1C). This synchronized differentiation is based on the assumption that in the absence of GLP-1 independent transit amplification, all PZ cells rely on GLP-1 activity and are developmentally equivalent.

To experimentally manipulate GLP-1 activity, we raised glp-1(bn18) mutants at permissive temperature (15°) and shifted synchronized adult animals to restrictive temperature (25°). Using REC-8 and HIM-3 antibody staining as markers, we analyzed the timing of meiotic entry among proliferative zone cells during a time course at the restrictive temperature (see Materials and Methods). Whereas there was no appreciable change in wild-type controls, in glp-1(bn18) mutants all PZ cells lost proliferative fate and initiated meiotic prophase within 10 hr at restrictive temperature (Figure 3A). We observed differentiation of PZ cells (becoming REC-8 negative, HIM-3 positive) in three phases. During the initial 4 hr, there was a moderate decrease of PZ cells. This was followed by a significant decrease between hours 4–6, when most of the PZ cells lose proliferative fate. Finally, between hours 6–8, a small subset of PZ cells remained REC-8 positive, completing entry to meiosis by hour 10. The glp-1(bn18) molecular missense lesion maps to an intracellular ankyrin repeat (Kodoyianni et al. 1992) and thus likely affects GLP-1 activity downstream of ligand-dependent cleavage and translocation to the nucleus. Similar time courses of meiotic entry were observed with two additional glp-1 temperature-sensitive loss-of-function alleles (q224 and e2141) that contain different missense mutations within the ankyrin repeats (Figure S2) (Kodoyianni et al. 1992), indicating that the kinetics of meiotic entry at restrictive temperature are not allele specific. We chose to further examine the bn18 mutant as it has the largest proliferative zone and therefore should be more comparable to wild type (Table 1). Currently, there is no direct readout for GLP-1 activity and reporters for GLP-1 transcriptional targets are just being developed (Kershner et al. 2014). Instead, we used changes in GLD-1 levels as an indirect readout because GLP-1 signaling indirectly inhibits accumulation of GLD-1 protein in distal germ cells (Hansen et al. 2004b); following shift of glp-1(bn18) to 25°, distal GLD-1 levels are elevated at the 2-hr time point (P. Fox and T. Schedl, unpublished results), indicating that GLP-1 activity has decreased significantly before the 2-hr point, which is propagated to alter GLD-1 protein levels through changes in translational regulation of the gld-1 mRNA (Lee and Schedl 2010).

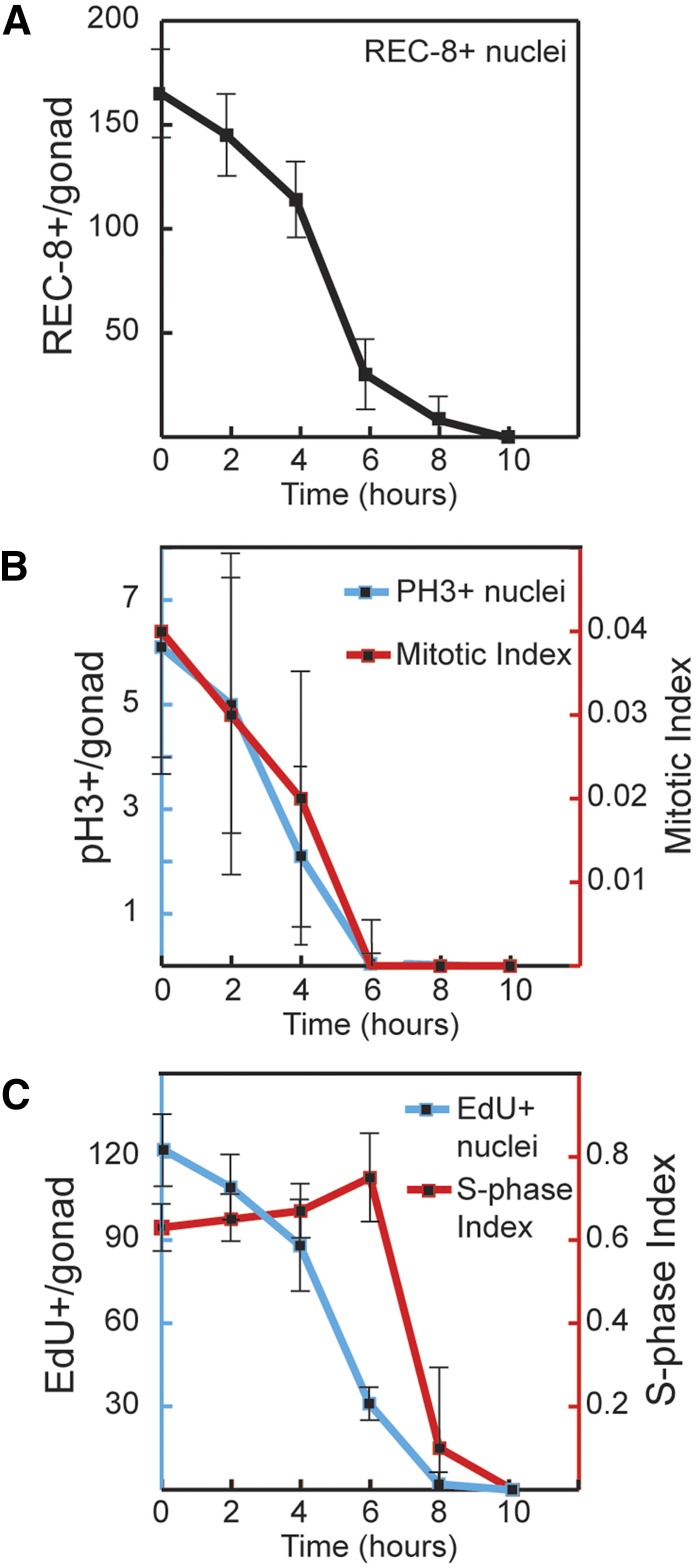

Figure 3.

Time course of meiotic entry and cell cycle progression following loss of GLP-1 activity. glp-1(bn18) mutants were shifted to restrictive temperature (25°) for the indicated time. The graphs show the following values plotted vs. time at restrictive temperature: (A) number of REC-8-positive PZ cells per germline, (B) number of pH3-positive PZ cells per germline (blue axis) and M-phase index (red axis), and (C) number of EdU-positive cells per germline (blue axis) and S-phase index (red axis). To analyze S-phase index, animals were given an EdU pulse for the final 30 min at restrictive temperature. (A) 0 hr, n = 49 germlines; 2 hr, n = 49; 4 hr, n = 53; 6 hr, n = 40; 8 hr, n = 28; 10 hr, n = 34. (B) 0 hr, n = 37; 2 hr, n = 30; 4 hr, n = 33; 6 hr, n = 45; 8 hr, n = 42. (C) 0 hr, n = 12; 2 hr, n = 9; 4 hr, n = 9; 6 hr, n = 12; 8 hr, n = 11; 10 hr, n = 25.

To analyze the spatial pattern of meiotic entry within the context of the model predictions, we scored the percentage of cells that were REC-8 positive on a per-row basis, where “row 1” includes the germ cells at the distal tip and “row 20” is 20 cell diameters proximal from the distal tip (Figure 4). In glp-1(bn18) mutants at permissive temperature (15°), the length of the proliferative zone (distance in cell diameters from the distal tip to the first meiotic prophase cell) was 13.6 ± 1.3 cell diameters (Figure 4A). The proliferative zone is followed by the meiotic entry region (Hansen et al. 2004a), which contains a mixture of PZ and meiotic prophase cells extending as far as 23 cell diameters from the distal tip. At hours 2 and 4, the length of the proliferative zone was nearly identical to the initial size (13.5 ± 1.4 cell diameters at 2 hr, 11.1 ± 1.1 cell diameters at 4 hr); however, the percentage of PZ cells decreased in the rows within the meiotic entry region (Figure 4, B, C, B′, and C′). From hours 4 to 6, the majority of cells in rows 1–13 have completed progression to meiosis, and at hour 6, cells in meiotic prophase were observed at the distal tip and throughout the region previously occupied by the proliferative zone (Figure 4, D and D′). The remaining PZ cells (REC-8 positive, HIM-3 negative) at the 6- and 8-hr time points were distributed throughout the distal 1–13 rows of the germline (Figure 4, D, E, D′, and E′). We made three important observations regarding these data. First, the PZ cells that enter meiosis during the first 4 hr at restrictive temperature were mostly located in the proximal-most rows or in the meiotic entry region. Second, the majority of PZ cells enter meiosis relatively synchronously between hours 4 and 6, and these cells are located throughout the proliferative zone and the meiotic entry region. Finally, the last PZ cells to enter meiosis (hours 6–10) were located throughout the distal-proximal ∼13-cell diameters of the former proliferative zone and were not restricted to the distal-most region. We interpret these results to indicate that progression to meiosis occurs relatively synchronously throughout the proliferative zone, consistent with the predictions from model 2: Equivalent PZ cells (Figure 1C).

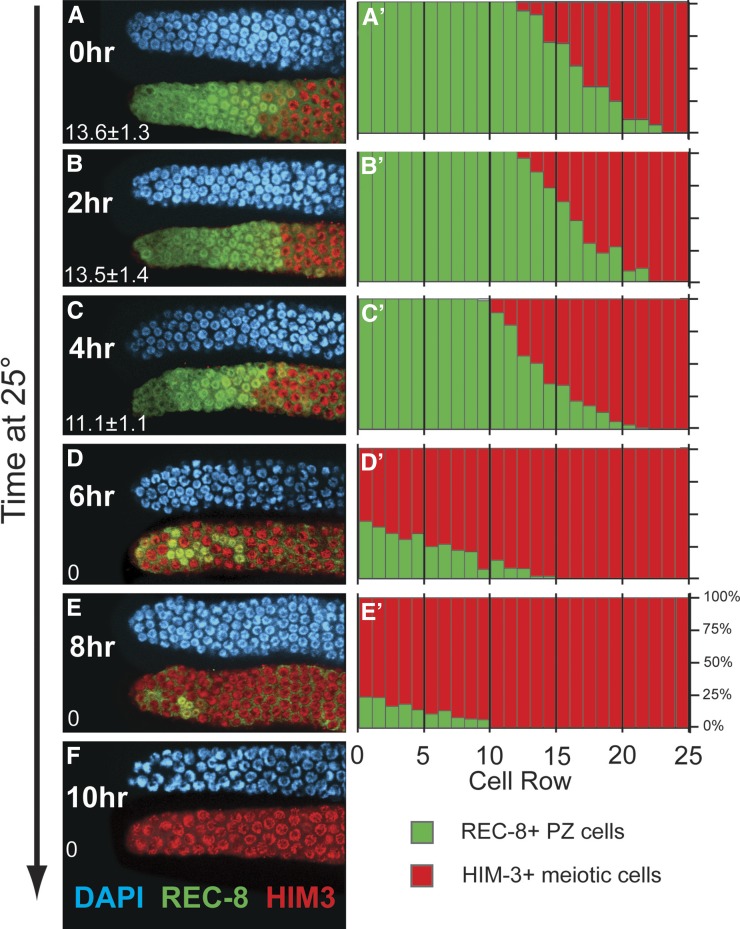

Figure 4.

Distribution of proliferative zone cells during and after loss of GLP-1 activity. glp-1(bn18) mutants were shifted to the restrictive temperature (25°) and harvested at the indicated times. (A–F) Distal region of the germline stained with DAPI (blue), REC-8 antibody (green), and HIM-3 antibody (red). The average length of the proliferative zone in cell diameters (from distal tip until the first meiotic prophase cell) is indicated in the lower left corner. Representative images are shown. (A′–E′) Graphs show the percentage of cells that are REC-8 positive (green) or HIM-3 positive (red) within cell rows defined by distance from the distal tip. The bulk of PZ cells enter meiotic prophase between hours 4 and 6 (C, C′, D, and D′), with the remaining minority of REC-8-positive, HIM-3-negative cells PZ cells at hour 6 distributed across an ∼13-distal-proximal-cell-diameter region or at hour 8 across an ∼10-cell-diameter region. 0 hr, n = 10 germlines, scoring ∼250 germ cells for each; 2 hr, n = 8; 4 hr, n = 9; 6 hr, n = 10; 8 hr, n = 9.

Our results and interpretation have important differences in comparison with a similar study performed by Cinquin et al. (2010), which are largely related to the means of assessing whether a cell has entered meiosis or is still a PZ cell. Cinquin et al. (2010) used DAPI staining and crescent-shaped morphology of some leptotene/zygotene nuclei as an indicator of induced meiotic entry kinetics in their analysis of glp-1(q224) mutants shifted to restrictive temperature. Between hours 0 and 5 they reported a proximal-to-distal wave of meiotic entry in rows 5–12, and the final cells to enter meiosis, in rows 1–5, entered synchronously between hours 5 and 6. The authors interpreted the synchronous population of cells in rows 1–5 to contain the germline stem cells and rows 5–12 to contain TA cells. However, the use of DAPI staining in this study did not allow detection of PZ cells remaining at hours 6–8 (Figure 4) because chromosome morphology does not allow an unambiguous classification of individual germ-cell fate [see also Figure S2 in which we analyze glp-1(q224)]. In contrast, the use of REC-8/HIM-3 costaining can distinguish between PZ cells and meiotic prophase cells, even when they are intermixed, as often occurs in the meiotic entry region in wild type and in certain incompletely penetrant germline tumor mutants (MacQueen and Villeneuve 2001; Hansen et al. 2004a; Fox et al. 2011; Gupta et al. 2015). To illustrate the distinction between antibody markers and DAPI morphology, Figure 2A (arrowhead) shows a cell that has entered meiosis (HIM-3 positive; REC-8 negative) whose nucleus shows spherical- rather than crescent-shaped DAPI morphology. This proves to be a key difference since REC-8/HIM-3 staining revealed that the final cells to enter meiosis at 6–8 hr were not limited to the distal end (rows 1–5) but rather distributed throughout the proliferative zone region (rows 1–13).

In addition to the wave of differentiation, a second prediction of model 1 is that after loss of GLP-1 activity and conversion of stem cells into TA cells, mitotic division should become spatially restricted to the distal-most region where the stem cells were located (rows 1–5) because these cells would go through rounds of transit amplification, which more proximal cells would have already initiated or completed. However, analysis of the spatial distribution of cells in M-phase over the temperature-shift time course showed a random distribution of pH3-positive cells along the distal-proximal PZ position (Figure S3).

Most PZ cells undergo a single cell division following loss of GLP-1 activity

If germline stem cells convert to TA cells, then we would expect these TA cells to undergo multiple rounds of mitotic division. To investigate this, we sought to determine how many cell divisions occur within the proliferative zone following loss of GLP-1 activity. We began by analyzing M-phase and S-phase at a population level during the temperature-shift time course (Figure 3, B and C). As expected, the loss of proliferative fate coincides with a steady decrease in both M-phase and S-phase. By 6 hr at restrictive temperature, essentially no cells were dividing. Similarly, DNA replication occurred until 8 hr. The late period of DNA replication from 6 to 8 hr occurs after completion of mitosis and likely corresponds to meiotic S-phase among the remaining PZ cells. Therefore, while significant cell division occurs subsequent to the shift to the restrictive temperature, these divisions are completed within 6 hr.

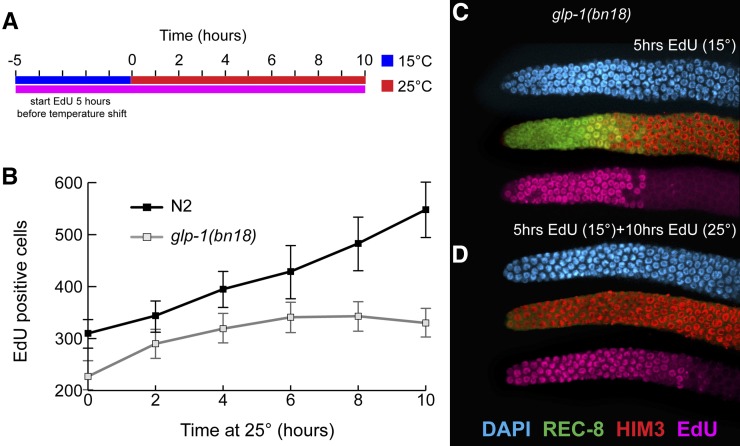

To estimate the total number of cell divisions on a population level, we employed an EdU incorporation assay whereby the expansion of cells could be quantified based on an increase of EdU-labeled cells (Figure 5). Animals were first given EdU for 5 hr at 15°, a feeding regimen sufficient to label all PZ cells (Figure 2F). Following this 5-hr EdU pulse, animals were then shifted to restrictive temperature while maintaining EdU feeding. Since all PZ cells are EdU positive after the initial 5-hr pulse, a subsequent increase in the number of EdU-positive cells (including both PZ cells and meiotic cells) can be directly attributed to mitotic division. In wild-type germlines shifted to 25°, the number of EdU-positive cells increases continuously over a 10-hr time course (Figure 5D). However, in glp-1(bn18) mutants, the number of EdU-positive cells initially increases but then reaches a plateau by 6 hr (Figure 5D). Consistent with our previous results, the timing of this plateau corresponds to the termination of cell division as assayed by pH3 staining above (Figure 3C). Based on the increase of EdU-positive cells in glp-1(bn18) from the start of the shift (227 ± 23) until 6 hr (340 ± 31), we deduce that ∼110 divisions occur on a population-wide level. As shown above, glp-1(bn18) mutants contain 97–128 mitotically cycling cells at steady state (15°) (Table 2). Therefore, the total number of divisions that occur after shift to the restrictive temperature corresponds closely to the number of cells that were initially mitotically cycling. The simplest explanation for this correlation is that, on average, each of the mitotically cycling cells completes a single division following the loss of GLP-1 activity.

Figure 5.

Cell division in glp-1(bn18) at restrictive temperature. (A) Wild-type and glp-1(bn18) adults were given a 5-hr pulse of EdU (pink line) at 15° and subsequently shifted to 25° with continuing EdU labeling (pink line). (B) Number of EdU-positive nuclei per germline vs. time at 25°. In wild-type N2, there is a continuous increase whereas in glp-1(bn18), the number of EdU-positive nuclei reaches a plateau by 6 hr. N2: 0 hr, n = 10 germlines; 2 hr, n = 10; 4 hr, n = 10; 6 hr, n = 6; 8 hr, n = 10; 10 hr, n = 10. glp-1(bn18): 0 hr, n = 11; 2 hr, n = 10; 4 hr, n = 10; 6 hr, n = 12; 8 hr, n = 7; 10 hr, n = 7. Error bars indicate standard deviation. (C and D) Representative image of glp-1(bn18) proliferative zone after 5 hr of EdU pulse at 15° (C) and after 10 hr at 25° (D) stained with DAPI (blue), REC-8 (green), HIM-3 (red), and EdU (pink).

How do the kinetics of progression to meiosis compare with cell cycle length and does this comparison agree with our assessment that most PZ cells undergo a single division? Previous work has shown that cell cycle length in the germline varies with temperature (Fox et al. 2011). To investigate the effect of the temperature shift and whether loss of GLP-1 activity affects cell division, we analyzed cell cycle kinetics during the initial period of the temperature shift time course. We measured G2+M+G1 after shift from 15° to 25° (see Materials and Methods). Both wild-type and glp-1(bn18) mutants show ∼100% EdU incorporation following a 3-hr pulse (Figure 2F). Based on this, we conclude that temperature, but not loss of GLP-1 activity, affects mitotic cell cycle kinetics during this time interval. In addition, we can extrapolate a maximum cell cycle length under these conditions. Based on G2+M+G1 lasting a maximum of 3 hr and corresponding to 40% of the cell cycle (Figure 2 and Table 3), the maximum length estimate for the total cell cycle is 7.5 hr (see Materials and Methods). Since most PZ cells enter meiosis within 6–8 hr of loss of GLP-1 activity, this cell cycle estimate is consistent with our conclusion that, on average, each of the actively cycling PZ cells divides once and completes the ongoing mitotic cell cycle during this time course.

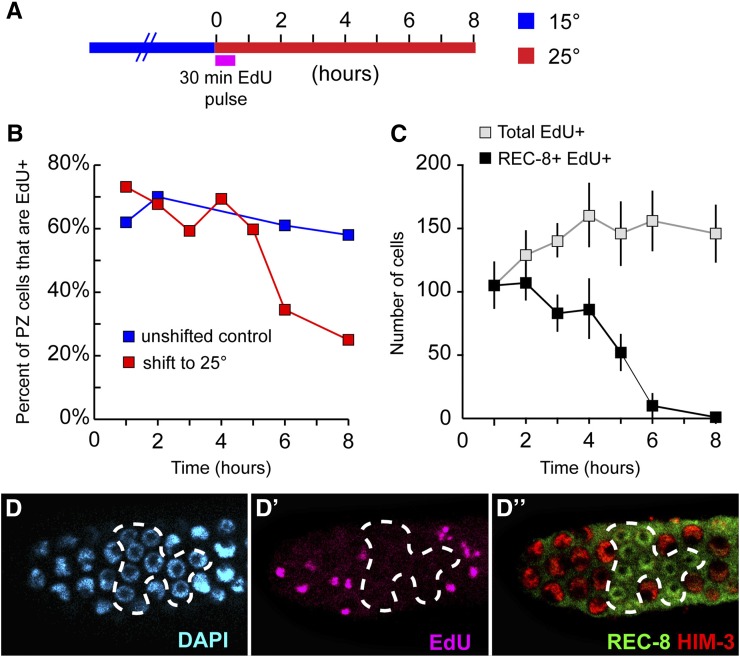

Timing of meiotic entry following loss of GLP-1 activity depends on mitotic cell cycle position

Since entry into meiosis following loss of GLP-1 activity is largely independent of distal-proximal position and since progression to meiotic prophase involves completion of mitosis, we hypothesized that the variation in meiotic entry timing among PZ cells depends on the distribution of PZ cells in different stages of the cell cycle. To determine whether mitotic cell cycle position correlates with the meiotic entry kinetics of individual cells, we first asked whether cells in different phases of the cell cycle enter meiosis at different times following loss of GLP-1 activity. We performed a pulse-chase experiment in which cells in S-phase at the start of the temperature shift were labeled with a brief EdU pulse, thus distinguishing them from unlabeled cells in G2/M, followed by a non-EdU chase (Figure 6A). Most PZ cells enter meiosis by 6 hr at 25°; however, we observed that EdU-negative cells were overrepresented among PZ cells remaining during the final 6–8 hr of the time course (Figure 6, B–D, D′, and D′′). Based on this, we conclude that the cell cycle position affected the kinetics of meiotic entry following loss of GLP-1 and that a subset of cells in G2/M at the start of the temperature shift retained proliferative fate longer than the surrounding cells in S-phase.

Figure 6.

Timing of meiotic entry following loss of GLP-1 depends on cell cycle position. Experimental setup is illustrated in A. glp-1(bn18) mutants were shifted to 25° while simultaneously initiating a 30-min pulse of EdU. This was followed by a non-EdU chase period that continued at 25°. Dissected germlines were analyzed with REC-8, HIM-3, EdU, and DAPI stains. (B) Graphs show the percentage of PZ cells (REC-8 positive) that were labeled with EdU. In unshifted controls, this ratio remains constant whereas in shifted germlines, the ratio dramatically decreases at 6 and 8 hr. At 6 and 8 hr, there are very few REC-8-positive cells remaining (see also Figure 3 and Figure 4), and the majority of these cells were EdU negative (∼30% EdU positive at 6 hr, ∼20% EdU positive at 8 hr). (C) The total number of EdU nuclei were categorized based on HIM-3 and REC-8 staining. Overall, the number of EdU-positive nuclei increases during the time course. Representative images of distal region stained with DAPI (D), for EdU (D′) and HIM-3 and REC-8 (D″) following 6 hrs at 25°. REC-8-positive, HIM-3-negative PZ cells (12 total, some in lower focal plane) are EdU negative while surrounding EdU-positive nuclei have already entered meiosis (REC-8 negative, HIM-3 positive). We note that the REC-8+ cells remaining at 6 hr (and 8 hr) are reminiscent of a clonal population of cells (see also Figure 4). (B) glp-1(bn18) 15°: 1 hr, n = 12 germlines; 2 hr, n = 9; 6 hr, n = 7; 8 hr, n = 11. glp-1(bn18) 25°: 1 hr, n = 11; 2 hr, n = 8; 3 hr, n = 7, 4 hr, n = 10; 5 hr, n = 10; 6 hr n = 13; 8 hr, n = 11. (C) 1 hr, n = 10; 2 hr, n = 8; 3 hr, n = 8; 4 hr, n = 10; 5 hr, n = 10; 6 hr, n = 12; 8 hr, n = 12.

When during the mitotic cell cycle does the decision to enter meiosis occur and how does this affect the timing of meiotic entry? Previous studies in yeast and in mammals suggest that a switch to meiosis occurs prior to meiotic S-phase (Honigberg and Purnapatre 2003; Baltus et al. 2006). However, cells in mitotic G2 (4N) in theory could divert to meiosis without an intervening mitotic division or further DNA replication. To test this, we analyzed glp-1(bn18) shifted to restrictive temperature while simultaneously initiating continuous EdU feeding. If PZ cells already in mitotic G2 directly switch to meiotic prophase, these cells would initiate meiotic prophase (become HIM-3 positive) while remaining EdU negative. Cells in G2 are observed throughout the proliferative zone (Fox et al. 2011); however, we failed to observe EdU-negative/HIM-3-positive cells within the distal-most 15 cell rows of the temperature shifted glp-1(bn18) germlines after 10 hr at restrictive temperature (Figure S4). Instead, all cells within this region were both HIM-3 and EdU positive. We conclude that, consistent with other organisms, cells in mitotic G2 are unable to switch directly to meiotic prophase.

Next we investigated whether in glp-1(bn18) temperature-shifted germlines PZ cells could switch from mitotic S-phase to meiotic S-phase. To explore the outcomes of cells in S-phase after loss of GLP-1 activity, we further analyzed the pulse-chase experiment above in which we labeled PZ cells in S-phase with a short EdU pulse at the start of the temperature shift (Figure 6A). Specifically, we asked when do the EdU-labeled cells enter meiosis and is there an increase of EdU-labeled cells that would indicate mitotic division? EdU-labeled cells began entering meiosis (becoming REC-8 negative, HIM-3 positive) within 2 hr at restrictive temperature, but between 4 and 6 hr, the majority of EdU-pulse-labeled cells became HIM-3 positive REC-8 negative (Figure 6C). We also observed that the number of EdU-labeled cells increased from 105 ± 18 initially to 160 ± 28 at hour 4, just before most of the labeled cells enter meiosis (Figure 6C). Since this pulse-chase experiment labels cells in both meiotic S-phase and mitotic S-phase, the earliest cells to enter meiosis were likely in meiotic S-phase and the later cells to enter meiosis were in mitotic S-phase. Importantly, the increase in number of EdU pulse-chased labeled cells over the time course indicates that a subset of these cells, presumably those in mitotic S-phase, underwent mitotic division prior to entering meiosis. These results indicate that shifting glp-1(bn18) to restrictive temperature did not switch cells in mitotic S-phase to meiotic S-phase before completion of mitosis.

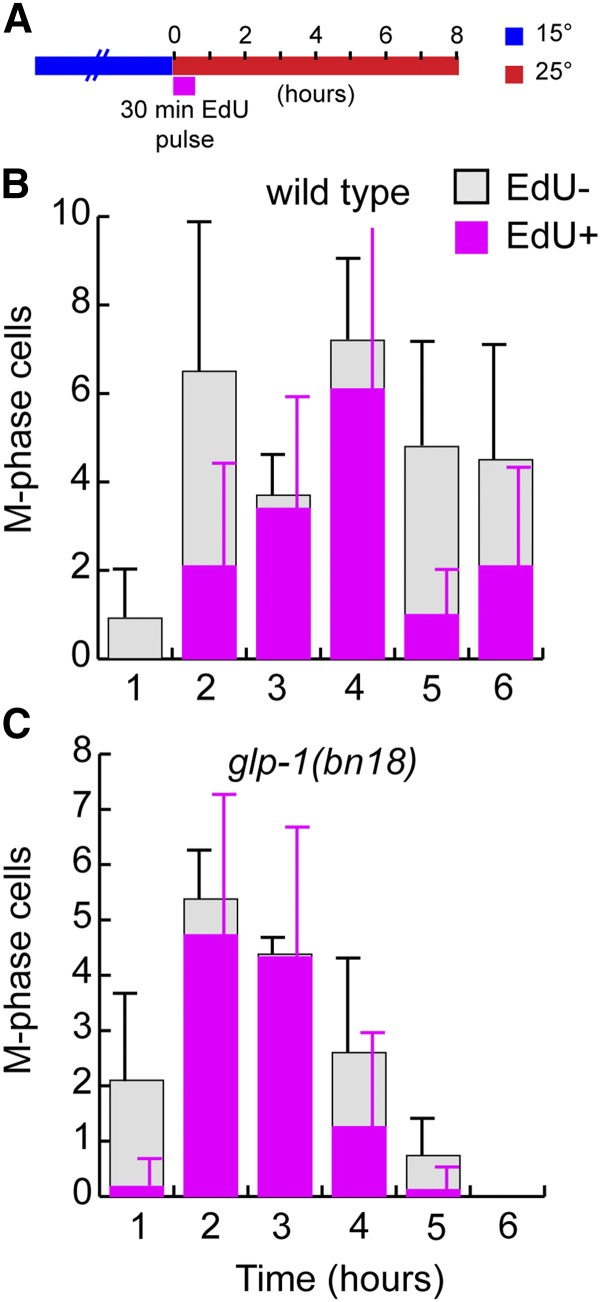

To determine the timing when these EdU pulse-labeled cells divide, we analyzed the mitotic divisions that occur after the shift to restrictive temperature. As above, glp-1(bn18) and wild-type controls were subjected to a pulse-chase experiment and given a pulse of EdU at the start of the temperature shift (Figure 7). Animals were then dissected at 1-hr intervals to stain for EdU and M-phase (pH3). As we have shown previously (Fox et al. 2011), this pulse-chase experiment allows us to observe the progression of labeled vs. unlabeled cells through M-phase. In both wild type and glp-1(bn18), the temperature shift appears to cause either an initial cell cycle delay or acceleration of M-phase progression, observed as a temporary decrease in M-phase observance. Following this, whereas wild type displays division throughout, glp-1(bn18) displays a steady decrease in total M-phase (both EdU positive and EdU negative), consistent with our results above. As expected, in both wild type and glp-1(bn18) the first cells to enter M-phase (hour 1) were in G2 at the time of the pulse and thus are EdU negative. Subsequently, during hours 2–4 EdU-positive cells are observed in M-phase, and specifically at hour 3 nearly all M-phase cells in both glp-1(bn18) and control are EdU positive. Following this, at hours 4–6, EdU-negative cells enter M-phase again, indicating a second division of these unlabeled cells during this time course. We conclude that cells in mitotic S-phase at the start of the temperature shift divide during hours 2–4 and then enter meiosis during hours 4–6. Based on this, loss of GLP-1 activity does not cause cells to switch from mitotic to meiotic S-phase. Instead, we can observe that these cells execute mitosis prior entering meiosis.

Figure 7.

Division of proliferative zone cells following loss of GLP-1 activity. (A) Illustrates the experimental setup. Wild-type control (B) and glp-1(bn18) mutants (C) were shifted to 25° while simultaneously initiating a 30-min pulse of EdU. This was followed by a non-EdU chase period that continued at 25°. Dissected germlines were analyzed with pH3, EdU, and DAPI stains. pH3-positive PZ cells were counted and scored as EdU positive or negative. Stacked bar graphs show the average number of EdU-positive or -negative M-phase cells per germline. Time indicates the duration at 25°. Early cell divisions are of mostly EdU-negative cells (hour 1), followed by a round of EdU-positive cells (hours 2–4) and a final round of EdU-negative cells (hour 5). The final round of EdU-negative cells is likely completing a second division following the shift to 25°. We note an initial depression of M-phase frequency in control and glp-1(bn18) at 1 hr, likely a consequence of the temperature shift. Whereas our other estimate of cell cycle length following shift from 15° to 25° based on G2+M+G1 analysis (see Figure 2F) indicates a maximum cell time of 7.5 hr, the analysis of pulse-labeled cells through M-phase here is consistent with a cell cycle time of 4–5 hr. This difference is likely due to an overestimate of cell cycle time on account of the G2+M+G1 assay providing a maximum length (see also Fox et al. 2011). (B) 1 hr, n = 25 germlines; 2 hr, n = 28; 3 hr, n = 24; 4 hr, n = 19; 5 hr, n = 23; 6 hr, n = 18. (C) 1 hr, n = 27; 2 hr, n = 26; 3 hr, n = 19; 4 hr, n = 23; 5 hr, n = 21; 6 hr, n = 20. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

We propose that, on average, each of the mitotically cycling cells in the proliferative zone will divide once following restrictive-temperature-mediated loss of GLP-1 activity. Our observations also suggest that a small fraction of proliferative zone cells complete two divisions during our glp-1(bn18) temperature shift experiment. In the pulse-chase experiment above (Figure 7), we observed that some EdU-negative cells executed two rounds of cell division: initially during hours 1–2 and subsequently at hours 4–5. This second round indicates that a subset of EdU-negative cells divide twice. In addition, we note that the last PZ cells to enter meiosis after the temperature shift are usually EdU negative (hours 6 and 8, Figure 6, B and D). These final remaining PZ cells often appear as clusters of four (Figure 4E; Figure 6, D, D′, and D′′), suggesting that they are lineage-related siblings with similar meiotic entry kinetics. Taken together, these observations suggest that a small number of cells in G2/M at the start of the temperature shift divide twice before entering meiosis, and these cells represent the final cells to complete entry into meiosis. Importantly, we note that the presumptive daughters of these cell divisions are not spatially restricted to the very distal proliferative zone region, but can be observed over an ∼13-cell diameter region (Figure 4E). We further investigated this by analyzing the distribution of cell division during the glp-1(bn18) temperature-shift time course (Figure S3). Indeed, at 4 hr after the temperature shift, we observed M-phases throughout the 13 distal-most rows. We suggest that whether a cell divides once or twice before entering meiosis depends on the timing by which GLP-1 activity falls below a threshold relative to cell cycle progression. Our results indicate that cells in either mitotic S-phase or G2 are committed to completing the ongoing mitotic cell cycle; therefore, GLP-1 activity must drop below this threshold prior to initiating S-phase to begin meiotic S-phase. We suspect that GLP-1 activity falls below this threshold during the course of mitotic cell cycle progression and the subsequent daughter cells begin meiotic S-phase. In the glp-1(bn18) temperature-shift experiment, for the majority of mitotically dividing cells this occurs during the concurrent mitotic cell cycle and only a single division occurs. For the minority of cells that undergo two divisions, we propose that GLP-1 activity persists above this threshold until after their first division and mitotic S-phase begins again, thus committing them to a second division. Evidently, this occurs only among cells already late in the cell cycle (G2/M).

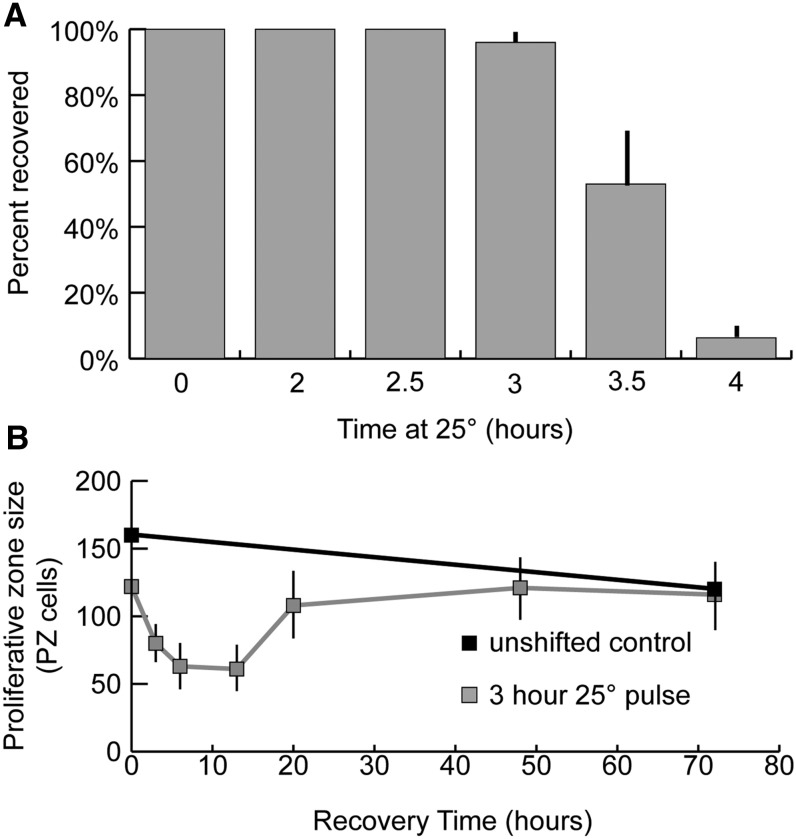

Recovery of proliferative fate in glp-1(bn18) by return to permissive temperature

We next investigated when during the GLP-1 inactivation time-course germ cells become irreversibly committed to meiotic development. glp-1(bn18) mutants were shifted to restrictive temperature for varying lengths of time and subsequently returned to permissive temperature (Figure 8A). After 3 hr at restrictive temperature followed by growth at permissive temperature, >95% of germlines recover to steady-state growth. When returned to permissive temperature, these recovering germlines undergo a brief period where the number of PZ cells falls until hours 3–12, followed by recovery to preshift size (Figure 8B). The proliferative zone in these recovering germlines always maintains a population of REC-8-positive, HIM-3-negative cells at the distal tip, and meiotic entry is not observed such that PZ cells would be displaced from the DTC niche by cells in meiosis. In mutants incubated for 4 hr or longer at restrictive temperature, all PZ cells enter meiosis and PZ recovery fails to occur. This loss of recovery ability corresponds with the decrease in mitotic cell division that we observed above (Figure 3B). Although the precise dynamics of GLP-1 activity during restrictive/permissive temperature shifts are unclear, our results are consistent with commitment to meiotic differentiation occurring in the same time frame as completion of mitotic division and the initiation of meiotic S-phase.

Figure 8.

Recovery of the proliferative zone in glp-1(bn18) following exposure to the restrictive temperature. (A) glp-1(bn18) mutants were shifted to restrictive temperature for the indicated length of time and then returned to permissive temperature. Animals were allowed to recover for 48 hr and subsequently scored for Glp (all PZ cells having entered meiotic prophase) phenotype. (B) Animals were shifted to 25° for 3 hr and subsequently returned to permissive temperature to allow recovery. Animals were harvested at the indicated time points, and the total number of REC-8-positive PZ cells were counted. The time indicates hours after returning to permissive temperature (15°). (A) 0 hr, n = 92 germlines; 2 hr, n = 37; 2.5 hr, n = 68; 3 hr, n = 101; 3.5 hr, n = 94; 4 hr, n = 90. (B) unshifted control: 0 hr, n = 17; 72 hr, n = 16. 3 hr, 25° pulse: 0 hr, n = 18; 3 hr, n = 19; 6 hr, n = 18; 12 hr, n = 10; 20 hr, n = 20; 48 hr, n = 16; 72 hr, n = 16. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Effect of disruption of the GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathway genes on meiotic entry timing

The GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathways act downstream of GLP-1 to redundantly promote entry into meiosis. While elimination of a single pathway does not prevent meiotic entry, single mutants that disrupt either pathway have been reported to affect the steady-state proliferative zone size (Eckmann et al. 2004). To analyze how these pathways may affect the timing of meiotic entry following loss of GLP-1 activity, we constructed double mutants with glp-1(bn18) and each of the GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathway members: gld-1, nos-3, gld-2, and gld-3. In addition, we also analyzed a fbf-2; glp-1(bn18) double mutant as fbf-2 has been shown to regulate proliferative zone size (Lamont et al. 2004). These double mutants display a range of proliferative zone sizes at 15° (Table 3). In general, the respective proliferative zone sizes paralleled what has been observed for the single mutants (Eckmann et al. 2004), albeit with glp-1(bn18) causing a decrease in size.

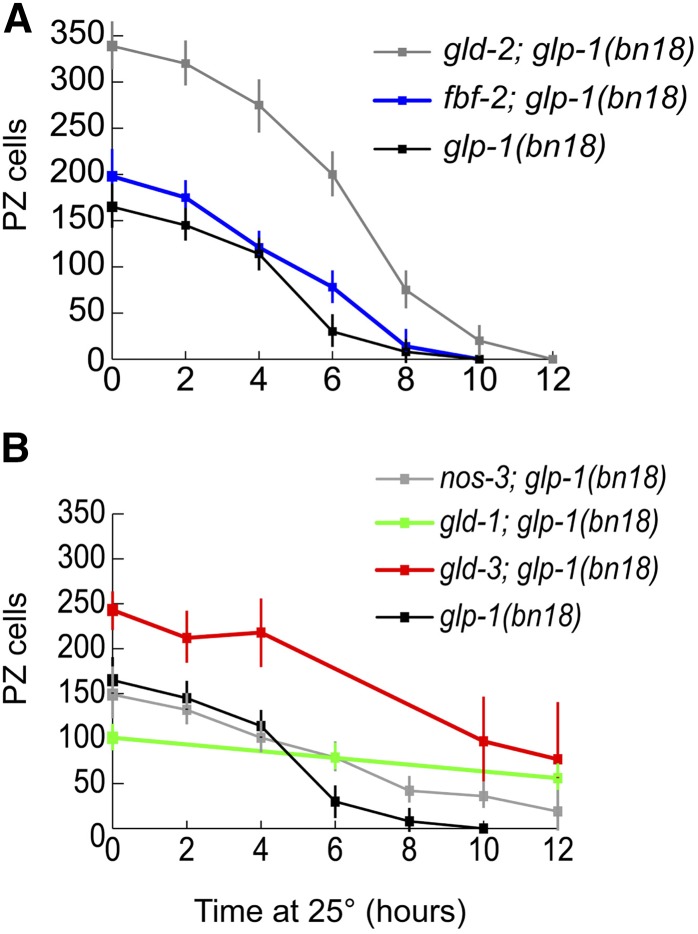

As described above, these double mutants were shifted to restrictive temperature (25°) as staged adults 24 hr past L4 (Figure 9). For gld-2; glp-1(bn18) or fbf-2; glp-1(bn18), we observed a few hours delay or no overall delay in the completion of meiotic entry. Interestingly, glp-1(bn18); gld-2 double mutants had a significantly larger proliferative zone than glp-1(bn18); however, the spatial pattern of meiotic entry following temperature shift was highly similar (Figure S5). For gld-1; glp-1(bn18), nos-3; glp-1(bn18), and gld-3; glp-1(bn18), we observed a significant delay or failure of germ cells to enter meiosis, even after 48 hr at restrictive temperature. In gld-3 and nos-3, the inhibition of meiotic entry was stochastic. After 12 hr at restrictive temperature, 3/15 gld-3; glp-1(bn18) germlines displayed a complete Glp phenotype (no PZ cells observed) and 4/14 nos-3; glp-1(bn18) germlines displayed a complete Glp phenotype. In addition, the gld-3; glp-1(bn18) non-Glp germlines at 12 hr displayed a large range of sizes (2–194 PZ cells, standard deviation 64). In gld-1; glp-1(bn18), the failure of meiotic entry was more consistent: 0/16 germlines displayed a complete Glp phenotype even after as long as 48 hr at restrictive temperature. Therefore, the effect of the various mutations on glp-1(bn18) induced-meiotic entry did not correlate with the original size of the proliferative zone at the start of the shift, whereas gld-2 had the largest initial proliferative zone size, it did not cause a significant delay in meiotic entry. In contrast, the gld-1- or nos-3-containing mutants had relatively smaller proliferative zone sizes but caused significant meiotic entry delay or inhibition. gld-1; glp-1(bn18) germlines displayed the smallest germline, but displayed the most penetrant inhibition of temperature-shift-induced meiotic entry.

Figure 9.

Effect of meiotic entry pathway gene mutations on the time course of meiotic entry following glp-1(bn18) temperature shift. Double mutants of glp-1(bn18) and likely null alleles of GLD-1/GLD-2 pathway genes were shifted to restrictive temperature and analyzed for number of PZ cells (REC-8 positive). Graph shows the number of PZ cells per germline vs. time at 25°. (A) glp-1(bn18): 0 hr, n = 14 germlines; 2 hr, n = 9; 4 hr, n = 10; 6 hr, n = 11; 8 hr, n = 7; 10 hr, n = 8. fbf-2; glp-1(bn18): 0 hr, n = 10; 2 hr, n = 10; 4 hr, n = 10; 6 hr, n = 10; 8 hr, n = 10; 10 hr, n = 14. gld-2; glp-1(bn18): 0 hr, n = 7; 2 hr, n = 6; 4 hr, n = 7; 6 hr, n = 6; 8 hr, n = 8; 10 hr, n = 12; 12 hr, n = 14. (B) nos-3; glp-1(bn18): 0 hr, n = 10; 2 hr, n = 10; 4 hr, n = 10; 6 hr, n = 9; 8 hr, n = 10; 10 hr, n = 10; 12 hr, n = 8. gld-1; glp-1(bn18): 0 hr, n = 12; 6 hr, n = 10; 12 hr, n = 10. gld-3; glp-1(bn18): 0 hr, n = 8; 2 hr, n = 7; 4 hr, n = 8; 6 hr, n = 8; 8 hr, n = 8; 10 hr, n = 10; 12 hr, n = 11.

Why do the gld-1, nos-3, and gld-3 mutations delay or inhibit entry into meiosis? Previous work has shown that gld-1 represses glp-1 (Francis et al. 1995; Marin and Evans 2003); we hypothesized that elevated GLP-1 activity within these mutants suppresses glp-1(bn18), such that the activity of glp-1(bn18) at 25° remains above a threshold for proliferative fate. To test this, we further reduced the activity of GLP-1 in gld-1; glp-1(bn18) and nos-3; glp-1(bn18) mutants with glp-1 RNAi feeding (Table 4). Indeed, addition of glp-1 RNAi increased the induced meiotic entry phenotype, suggesting that gld-1; glp-1(bn18) and nos-3; glp-1(bn18) mutants contain elevated GLP-1 activity that suppresses the glp-1(bn18) mutation.

Table 4. glp-1 RNAi enhances glp-1(bn18) in nos-3 and gld-1 mutants.

| Genotype | RNAi | % Glpa | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| glp-1(bn18) | gfp | 100 | 21 |

| glp-1 | 100 | 26 | |

| glp-1(bn18); nos-3 | gfp | 61 | 74 |

| glp-1 | 96 | 71 | |

| glp-1(bn18); gld-1 | gfp | 0 | 43 |

| glp-1 | 33 | 47 |

Adult animals were shifted to RNAi plates at 25° for 24 hr. Glp indicates the absence of PZ cells as determined by REC-8 staining.

Since the timing of meiotic entry in glp-1(bn18) single mutants depends at least in part on cell cycle position, it stands to reason that the delays in meiotic entry could also be partially caused by changes in cell cycle kinetics. Therefore, we analyzed mitotic cell cycle progression in the double mutants by measuring S-phase index, M-phase index, and G2+M+G1 length at 15° (Figure S6). For nearly all the double mutants, all three cell cycle parameters correlated well with values obtained with both wild-type and glp-1(bn18) single mutants. However, gld-3; glp-1(bn18) mutants displayed a lower S-phase index and longer G2+M+G1 length, suggesting that increased cell cycle length may contribute to the delay in meiotic entry in the gld-3; glp-1(bn18) mutants shifted to restrictive temperature.

As a measure of PZ function, the expectation is that mutants with a larger PZ should result in a proportional increase in the number of germ cells that enter meiosis (PZ output), as is observed comparing wild type and glp-1(bn18) at 15° (Table 1 and Table 2). We therefore determined the output of gld-2; glp-1(bn18) and gld-3; glp-1(bn18) double mutants (Table 2). Surprisingly, relative to wild-type germlines, the proliferative zone output of these double mutants was not proportional to their respective proliferative zone size; for example, the PZ in wild type is 235 cells with an output of 155 cells per 10 hr while for gld-2; glp-1(bn18) the PZ is larger, 339 cells, but with an output of only 133 cells per 10 hr. The reason for this is unclear; one possibility is that there is a delay in the transition from mitotic cycling to overt meiotic differentiation (becoming HIM-3 positive), which may not be surprising given the role of GLD-2 in promoting meiotic entry.

Discussion

This study was designed to distinguish between two models for the organization of the stem cell meiotic entry system in the C. elegans germline: (1) whether there is a proliferative zone containing GLP-1-signaling-dependent distal stem cells followed by GLP-1-signaling-independent proximal TA divisions or (2) a proliferative zone containing stem and progenitor cells that are all GLP-1-signaling-dependent/developmentally equivalent (Figure 1). The two models predicted distinct phenotypic outcomes for PZ cells after loss of GLP-1 activity through manipulation of a temperature-sensitive loss-of-function mutant. Following loss of GLP-1 activity, we found that entry into meiosis was largely synchronous and independent of distal-proximal position and that the location of the last cells to undergo mitotic division was also independent of distal-proximal position. These results are not consistent with the model of GLP-1-independent TA divisions (model 1), which predicts that, following loss of GLP-1 activity, meiotic entry would occur in a proximal-to-distal temporal progression and that the last cell divisions would be spatially restricted to the distal-most region where the stem cells have converted to TA cells. Furthermore, we found that following shift of the glp-1(ts) mutant to the restrictive temperature, the majority of cells undergo a single mitotic division and complete the ongoing mitotic cell cycle prior to entry into meiosis based on kinetic studies showing (1) that there is an approximate doubling in cell number relative to the initial number of mitotically cycling cells, (2) that the estimated maximum cell cycle length (5–7.5 hr) is similar in timing to when the majority of germ cells entered meiosis (6–8 hr), and (3) that mitotic S-phase and G2 phase cells are not able to enter meiosis without an intervening mitotic division.

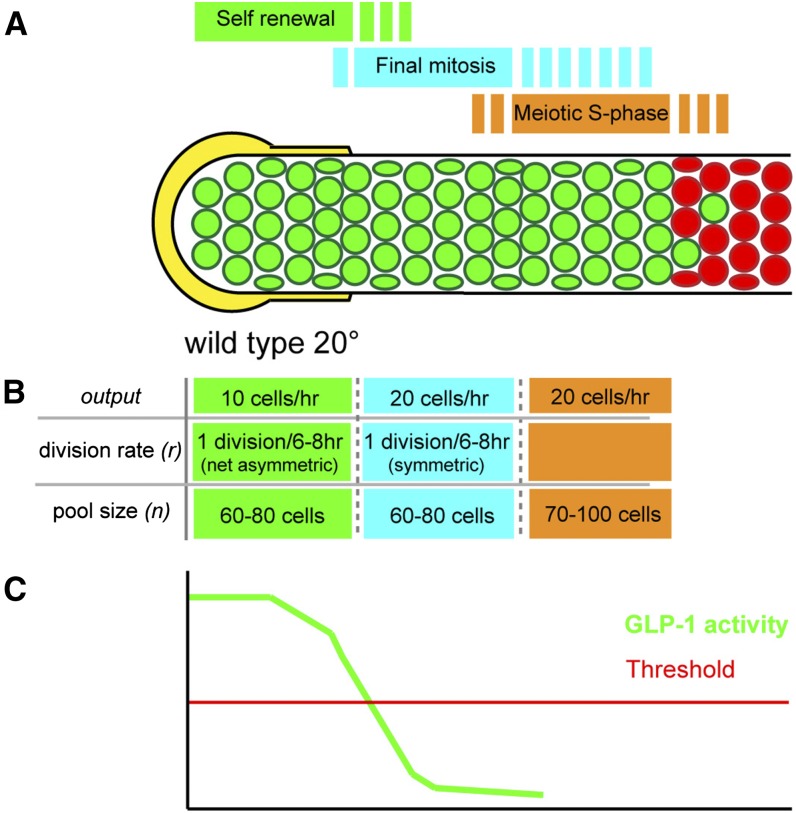

Model of proliferative zone dynamics

To begin to provide an understanding of how all of the mitotically cycling cells display GLP-1-signaling dependence, we present a population-based model of proliferative zone dynamics in the wild-type adult hermaphrodite germline. The model is based on the finding that the niche DTC plexus is large (Byrd et al. 2014) and could support a large stem cell population (see below) and that, when GLP-1 activity is lost, proliferative zone cells complete the ongoing mitotic cell cycle and begin meiotic development. Our model of the proliferative zone contains three distinct pools of cells that represent three sequential stages of PZ cell development: (1) self-renewing stem cells; (2) progenitors undergoing a final mitotic division; and (3) meiotic S-phase, which precedes overt meiotic differentiation. According to this model, the switch from pool 1 to 2 occurs when GLP-1-signaling activity falls below a threshold and is interpreted by the cell. As cell cycling is continuous among the PZ cells (no quiescent cells), this switch occurs during the course of mitotic cell cycle progression, and the resulting symmetric daughter cells both begin meiotic S-phase (enter pool 3).

The model incorporates cell cycle rate and overall proliferative zone output to estimate the size of each distinct pool and their individual output to describe the proliferative zone at steady state (Figure 10; wild type at 20°). For each pool of cells, the output is determined by the number of mitotically cycling cells (n), their rate of division (divisions/hour) (r), and the fate of the daughter progeny (whether each daughter cells remains within or exits the pool). For pool 1 (green, Figure 10B), steady-state self-renewal requires that for each division that occurs, on a population level, one daughter remains and one daughter exits the pool. Accordingly, each division yields an output of one cell. Therefore the output of pool 1 can be represented as

| (1) |

where n1 is the number of dividing cells in pool 1 and r is the division rate (divisions/hour). For pool 2 (teal, Figure 10B), where GLP-1 activity is lost prior to division, both daughter cells exit the pool (differentiate). Therefore, as opposed to pool 1 where a single division yields an output of one cell, in pool 2 each division yields an output of two cells. The output of pool 2 can be represented as follows:

| (2) |

At steady state, the output of pool 1 and pool 2 are interrelated since each cell that exits pool 1 (and enters pool 2) will eventually divide within pool 2 to generate two daughter cells that exit pool 2. Therefore, the output of pool 2 is twice the output of pool 1. Since cell division does not occur in pool 3 cells, the output of pool 2 and the overall output of the proliferative zone (output3) are equal. Therefore, the output of pool 1 and pool 2 relate to the overall output of the proliferative zone as follows:

| (3) |

Previously, we have described that the wild-type cell cycle length at 20° is 6–8 hr and the overall output of the proliferative zone is 20 cells/hour (Fox et al. 2011). Therefore, under steady state, we predict that the output of pool 1 in a wild-type germline is 10 cells/hour and the output of pool 2 is 20 cells/hour. A total of 60–80 cells, each dividing once every 6–8 hr, would generate an output of 10 cells/hour in pool 1, and an equal number of cells with an equal division rate would generate an output of 20 cells/hour in pool 2. Pool 3 (orange, Figure 10B) is composed of cells in meiotic S-phase, which will progress to meiotic prophase in the meiotic entry region. This pool of cells is included within the proliferative zone population-based EdU/BrdU incorporation studies that place all germline S-phase cells within the REC-8-positive/HIM-3-negative proliferative zone (Crittenden et al. 2006; Jaramillo-Lambert et al. 2007; Fox et al. 2011). Direct measure of the length of meiotic S-phase would allow one to estimate the size of this pool by relating flux of cells through this stage with the overall output rate of 20 cells/hour. For example, a meiotic S-phase length of 1 hr would suggest that 20 cells are in meiotic S-phase at any given time, whereas a length of 10 hr would suggest 200 cells. Previous measurements indicate that mitotic S-phase is ∼50–60% or 3–5 hr of the total mitotic cell cycle, which would correspond to 70–100 cells in meiotic S-phase, given an equivalent length (Fox et al. 2011). Although direct measure of meiotic S-phase length remains technically difficult, our previous work allowed us to estimate the number of nondividing cells within the proliferative zone. Since cell division is continuous among the mitotically dividing cells in pools 1 and 2, these nondividing cells correspond to pool 3. We previously estimated this to be 30–40% of the total proliferative zone (or 70–100 cells) (Fox et al. 2011). This estimate of 70–100 cells in meiotic S-phase is consistent with a length of meiotic S-phase of 3–5 hr, which, as discussed above, corresponds to the length of mitotic S-phase. Therefore, we propose that pool 3 contains 70–100 cells mostly undergoing meiotic S-phase. Together, our estimates for the size of pools 1–3 predict that the wild-type proliferative zone contains 190–260 cells. Indeed, this agrees with the experimental average of ∼230 PZ cells that we observe when counting REC-8-positive/HIM-3-negative cells.

Figure 10.

Model of proliferative zone composition and dynamics for the wild-type adult hermaphrodite. The proliferative zone in wild type is modeled based on our findings from analysis of meiotic entry behavior and mitotic cell cycle properties of germ cells following loss of GLP-1 activity (see text for details), which likely correspond to loss of the activity of the downstream transcriptional targets of GLP-1 signaling. The proliferative zone contains three pools (A and B), self-renewing stem cells (green) at the distal end, cells undergoing the final mitotic division (teal), and cells in meiotic S-phase (orange), which exist in partially overlapping regions (A). From measured proliferative zone output and division rate (r) in wild type at 20°, and the predicted behaviors of the cells in the three pools, the size of each pool can be estimated (B). Estimates for output and division rate are taken from Fox et al. (2011). As stem cell (pool 1) daughters progress proximally and escape the influence of the DTC plexus, they pass below a hypothesized threshold of GLP-1 activity (C), which results in loss of self-renewal activity, completion of the ongoing mitotic cell cycle (pool 2), and then meiotic S-phase (pool 3).

Our model framework can be used to describe other conditions where there is a steady state of proliferation and meiotic entry, measured PZ cell number, cell cycle time and PZ output (Figure S7). For wild type at 15°, 20°, and 25°, measured cell cycle time and output scale with increasing temperature resulting in the predicted stem cell pool, as well as the pool 2 size, being remarkably constant between temperatures (∼60–90 cells). In contrast, glp-1(bn18), while having the same cell cycle time as wild type at 15°, has a smaller proliferative zone output leading to a smaller predicted stem cell pool (49–65 cells, Figure S7), likely as a consequence of decreased GLP-1 signaling at the permissive temperature. Importantly, the model predicts a glp-1(bn18) proliferative zone (pool 1–3) of 133–195 cells, which is comparable to the experimentally measured size of 165 ± 26. We are not able to apply the model framework to gld-2 and gld-3 mutant germlines with larger PZs, given the finding that the PZ output was not proportional to the increased PZ size; this is possibly due to a delayed transition to overt meiotic entry in these mutants, which is consistent with the known function of GLD-2 and GLD-3 in meiotic entry.

Relating the activity of GLP-1 and the GLD-1/GLD-2 pathways to proliferative zone size

Detailed cytological analysis of the adult hermaphrodite DTC plexus reveals that short processes from the DTC intercalate between germ cells extending as far as 8–9 cell diameters from the distal tip (Byrd et al. 2014). These observations are consistent with the possibility of ligand-dependent GLP-1 signaling occurring as far 8–9 cell diameters from the distal tip, although it remains unknown how rapidly GLP-1 signaling is lost after germ cells move away from the membrane-bound ligand. Thus the DTC plexus niche is large and can accommodate a large stem cell population. The size of pool 1 in our model is 60–80 cells (Figure 10), and, interestingly, we find that the distal most 8–9 cell diameters in wild type contain ∼70–90 cells. As pool 1 cells are displaced proximally through distal cell divisions, they lose contact with the ligand containing DTC plexus processes and pass below threshold GLP-1 activity necessary for self-renewal and complete the ongoing mitotic cell cycle before initiation of meiotic S-phase. Thus cells in pool 2 are undergoing GLP-1-dependent mitosis as a consequence of completing the cell cycle that was ongoing when the threshold was passed. However, it is unlikely that all cells transition from pool 1 to pool 2 precisely at this 8- to 9-cell-diameter boundary. Stochastic differences in GLP-1-signaling activity related to the extent of the intercalating DTC process could cause individual cells to drop below the threshold earlier or later. Another important variable is the cell cycle position of PZ cells as they exit the DTC plexus, especially if the switch to undergoing a final division occurs only during a critical window of the cell cycle. For example, a drop in GLP-1 activity may cause a cell at an early stage of the cell cycle to undergo its final division while a cell at a later stage of the cell cycle may have passed this window, after which this signal is not interpreted until the next cell cycle. These variables may account for the few scattered cells that show late overt meiotic entry in the meiotic entry region and the intermixing of M-phase and meiotic S-phase among PZ cells (Hansen et al. 2004a; Crittenden et al. 2006). The predicted stem cell pool size for glp-1(bn18) at 15° is 45–60 cells (Figure S7), which would appear to be smaller than the number of cells that are in intimate contact with the DTC plexus. This difference can be explained by the reduced activity of glp-1(bn18) and the likely possibility that the density of the GLP-1 ligand falls with distance from the distal tip cap, which together result in cells passing through the threshold of GLP-1 activity before cells leave the 8- to 9-cell-diameter DTC plexus.

Downstream of GLP-1 signaling, the GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathways act in parallel to regulate entry into meiosis. Disruption of these genes affects PZ size, suggesting that the decision to enter meiosis may be an interplay of the fall/threshold of GLP-1 activity and the rise/threshold of GLD-1 and GLD-2 meiotic entry activity (Hansen and Schedl 2013). We observed distinct meiotic entry phenotypes when these genes were disrupted in the glp-1(bn18) temperature-shift experiment. gld-2 and fbf-2 mutants had germlines with larger PZs; however, they did not cause a significant delay in shift-up meiotic entry kinetics. In contrast, gld-1 and gld-3 mutations, and to a lesser extent nos-3, significantly inhibited meiotic entry in the glp-1(bn18) temperature-shift experiment. These phenotypes did not correlate with the steady-state size of the proliferative zone, whereas gld-1 caused a decrease in proliferative zone size and gld-3 resulted in a larger proliferative zone. For both of these mutants, complete meiotic entry was variable or observed only when glp-1(bn18) temperature shift was combined with glp-1 RNAi. Therefore, we suggest that disruption of gld-1 and gld-3 causes an increase in GLP-1-signaling activity or alters the threshold by which germ cells respond to GLP-1 activity, such that glp-1(bn18) retains function at restrictive temperature.

Mutants and conditions that disrupt animal physiology (e.g., dietary restriction) have a smaller adult proliferative zone, at least in part through decreased expansion of the stem cell pool during larval development (Michaelson et al. 2010; Dalfo et al. 2012; Korta et al. 2012); maintain a smaller stem cell pool; and likely have a small proliferative zone output at steady state in adulthood. Physiological pathways are likely to be largely acting in parallel to GLP-1 signaling in the control of the stem cell pool size (Hubbard et al. 2013). Our model may provide a useful framework for examining how the adult proliferative zone responds to changes in physiological conditions.