Abstract

Nutrients exert unique regulatory effects in the perinatal period that mold the developing immune system. The interactions of micronutrients and microbial and environmental antigens condition the post-birth maturation of the immune system, influencing reactions to allergens, fostering tolerance towards the emerging gastrointestinal flora and ingested antigens, and defining patterns of host defense against potential pathogens. The shared molecular structures that are present on microbes or certain plants, but not expressed by human cells, are recognized by neonatal innate immune receptors. Exposure to these activators in the environment through dietary intake in early life can modify the immune response to allergens and prime the adaptive immune response towards pathogens that express the corresponding molecular structures.

Keywords: allergens, early life, immune system, micronutrients, pathogens

INTRODUCTION

The neonatal immune response is rapidly modulated at birth through encounters with environmental antigens, immune activators, and biological response modifiers, including those present in colonizing microorganisms and dietary substances.1–3 Nutrients are cofactors and activators for the developing immune system.4 Developmental programming in the context of these interactions leads to characteristic growth patterns in early life that are associated with altered risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer.5–7 Recent studies indicate that perinatal nutrient deficiency is associated with reduced thymic function in later life.8,9 The underlying mechanisms involve the interaction of genetic imprinting, the fetal neuroendocrine system, maternal factors, the neonatal microbial flora, and antigen exposure after birth.10–13

Nutrients regulate the priming of immune response postnatally through effects on innate immune signal transduction pathways and immune cell development, thereby affecting early sensitivity to allergens, tolerance towards the emerging gastrointestinal flora and ingested antigens, and host defense against potential pathogens.14–16 Micronutrients, such as vitamin A, are critical for the early development of lymphoid cells in the gastrointestinal tract-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) including Peyer’s patches, the mesenteric lymph nodes, lamina propria, and gut epithelium.17

Neonates rely on the innate immune system. The weaker response of their monocytes and macrophages to Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands is associated with increased risk of infection.18 Nutrients and growth factors present in human milk are specific regulators and inducers of innate immune response.14 The fatty acid composition of milk has been found to alter the balance of circulating immune cell subpopulations and cytokine responses in early life.19,20 Adequate levels of vitamin A and vitamin D promote gut integrity and mucosal immune function in the neonate, while deficiencies of these micronutrients can cause impaired immune response.21,22 Maternal micronutrient deficiencies in selenium, and iron have direct effects on infant T lymphocyte and natural killer (NK) cell populations.23,24 Maternal vitamin E levels appear to influence allergic sensitivity.25 Replacement of critical micronutrients, such as zinc or vitamin A, when these are depleted during infection can substantially enhance recovery from specific infections through effects on host defense mechanisms.26,27 The activities of certain ingested plant and environmental microbial components, which present pattern recognition structures to the neonate, are also relevant to the early development of immune response. Molecular structures present on microbes and certain plants, but not expressed by human cells, are recognized by innate immune receptors analogous to the TLRs. For example, edible plants and their products, such as tea, mushrooms, and apples, express alkylamines that are recognized by human gamma delta T cells and trigger an immune response.28 Others, such as beta glucans, which are present in yeast and fungi as well as mushrooms, seaweed, and barley, stimulate hematopoiesis and innate immune response, modify response to allergens, and may prime the adaptive immune response towards the corresponding pathogens.

PERINATAL MALNUTRITION

Perinatal malnutrition has long-term effects on postnatal development. This concept, which was advanced by Barker as the “developmental origins of health and disease” hypothesis,29 is relevant to postnatal maturation of the immune response. McDade et al.30 reported that adolescents who were small for gestational age (SGA) at birth had lower thymopoietin levels when compared to adolescents who were appropriate for gestational age (AGA) at birth. The thymopoietin levels during adolescence correlated with growth in length during the first year of life in both groups. The probability of mounting a positive antibody response for adolescents who were SGA and also undernourished at the time of immunization was lower compared to adolescents who were AGA.8 Moore et al.31 have reported similar findings in adults using the same purified Vi surface polysaccharide extracted from Salmonella typhi. Interestingly, while they found a correlation for both the IgG and IgM antibody responses to Vi vaccine with birth weight, they did not find these responses to rabies or typhoid vaccine. The studies suggest that polysaccharide T-independent immune response may be specifically compromised by fetal growth retardation. 31

Prenatal stress can program the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis and may cause imprinting effects on the immune response; this has led to reduced thymic function in animal models that are analogous to humans undergoing postnatal maturation of the immune response.32,33 Maternal psychological stress is associated with a shorter length of gestation and consequent lower birth weight,34 and has recently been shown to affect cytokine secretion patterns in adult life.35 Increased cortisol levels after stress in pregnant rats led to altered gene expression of the placental glucose transporter, suggesting a potential impact on transplacental glucose transport to the fetus.36

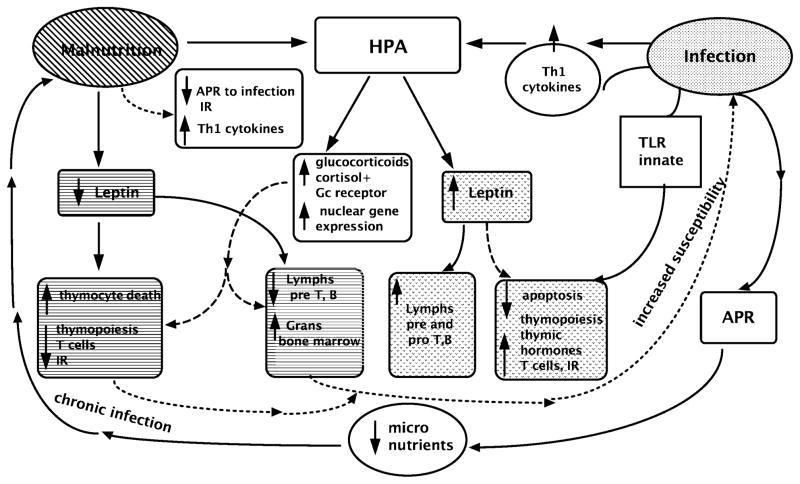

Experimental undernutrition alone has recently been reported to program the HPA axis, leading to increased placental transfer of glucocorticoids to the fetus and increased glucocorticoid response after birth in response to stimulus.37 Activation of the HPA axis is also central to the etiology of immunodeficiency in malnutrition, where hypercortisolemia is a common finding. Cortisol binds to the glucocorticoid receptor in the cytosol, translocates to the nucleus, and promotes gene transcription. Some of the interactions are presented in Figure 1. A recent study reported by Manary et al.38 of protein-deficient, marasmic children with or without acute infection showed that an increase in free cortisol was found only in infected children and the level was equivalent in both marasmic and well-nourished children. This may indicate that hypercortisolemia in malnutrition is due to subclinical infection. Marasmic children did have greater amounts of glucocorticoid receptors translocated to the nucleus compared to well-nourished control groups, regardless of infection.38 However, the expected effect of hypercortisolemia on proteolysis was lacking in marasmic, infected children, suggesting either that intracellular cortisol was not secreted or that the cortisol-binding receptor was inactive.38

Figure 1. Interactive effects of malnutrition and infection on immune response.

Illustration of some of the ways in which malnutrition and infection modulate immune response and central involvement of the hypothalamic pituitary axis, as described in the text. Abbreviations: APR, acute-phase response; IR, immune response; lymphs, lymphocytes; grans, granulocytes; pre T, B, early uncommitted T and B lymphocytes in bone marrow; Pro T, B early committed T and B lymphocytes in bone marrow; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

Malnutrition leads to reduced production of thymic hormones. Lowered levels of thymulin were observed in malnourished children39 and in children with zinc deficiency alone.40 Leptin, the adipocyte-secreted hormone that regulates weight centrally, also has cytokine-like activities. Leptin regulates the thymus by increasing thymopoiesis and inhibiting apoptosis when thymic activity is induced by other activators.41 While leptin is decreased in malnutrition, glucocorticoid hormone levels are increased, and the combination has been identified as the key mechanism involved in the loss of thymocytes and thymic atrophy.41 Malnutrition-associated immune deficiency enhances susceptibility to infections and cytokine activation.42 Tumor necrosis factor and interleukins 1, 6, and 8 induce fever and the hepatic synthesis of acute-phase reactant proteins, such as C-reactive protein (CRP); they also inhibit production of serum albumin and transthyretin.43 Shifts in storage pools of micronutrients occur during the acute-phase response and cause transient alterations in circulating levels of iron, zinc, and copper. This is due to transport by newly synthesized micronutrient-binding proteins such as ferritin, metallothionein, and ceruloplasmin.44 A recent study showed that genome-level alterations of zinc homeostasis is prevalent in clinical pediatric septic shock.45 Neonatal response to infection or “sterile infection” elicited by bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the main component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, has a potential impact on both the programming of immune response and brain development.46 Although malnutrition is associated with reduced cytokine response to antigen in vitro, the levels of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines in vivo are increased.44,47 Importantly, neonates appear to have a reduced compensatory anti-inflammatory response and may, therefore, be at greater risk for inflammatory damage.48 In recent studies, we reported that, compared to adults, the neonatal cytokine response is specifically deregulated in response to bacteria and has a tendency towards an uncompensated pro-inflammatory response. We observed that a lower percentage of monocytes produced cytokine responses to a panel of microbes but that the levels of cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 secreted in response to the same microbes were actually higher than those of adults.49,50

The thymus is selectively sensitive to nutritional injury and specifically important to the formative phases of immune development. Programmed involution of the thymus develops gradually over the first decades of life, and recent studies show that functionally active peripheral perivascular space thymic components predominate in adult life.51,52 However, this tissue continues to be responsive to nutrients, suggesting that the regulatory effects governing neuroendocrine-thymus interactions continue to be effective.52 Healthy neonates have higher levels of plasma zinc and bioactive thymulin compared to their mothers, and emerging studies of change over the first weeks of life in relationship to growth hormone levels and immune cell populations suggest that programmed interactions with the developing immune system evolve rapidly in the postnatal period.53

Malnutrition is a major cause of immune deficiency leading to greater frequency and severity of common infections.42 Primary malnutrition is common among children of all socioeconomic strata in wealthy industrialized societies due to poverty, lack of education, food allergies, inappropriate or limited diet, or eating disorders.54 Inadequate intake of micronutrients, including vitamins A and E, calcium, iron, and zinc, are prevalent among children under the age of 10 years, and they often go unrecognized. Children comprise a significant part of increasingly large immigrant populations in industrialized urban settings, where they may live in impoverished circumstances and have less access to health care. Such children are especially vulnerable to the effects of nutrient deficiency.

EFFECTS OF SPECIFIC MICRONUTRIENTS

Micronutrients have a major impact on immune response, through antioxidant activities and modulation of cytokine expression. Antioxidant enzymes, such as copper, zinc, and manganese superoxide dismutases, require trace metals for biological activity, and these enzyme reactions protect against oxidative damage caused by free radical formation during immune response and other biological reactions. Intracellular redox balance has a signaling role in immune cell development and function, and the antioxidant effects of micronutrients regulate cytokine production. Table 1 summarizes some of the main findings described in the following sections.

Table 1.

Effects of micronutrients on neonatal immune response.

| Nutrient | Target cells | Effect on development of immune system | Interactions in infection | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc | T cells, NK cells, B cells | Deficiency impairs immune response, ↓ hematopoiesis | Levels are rapidly depleted | Deficiency ↑ glucocorticoid ↓ pre T cell and B cells via Bcl-2 →apoptosis |

| Lymphopenia, dermatitis, enteritis | Repletion ↑ recovery | Required for thymic hormone function | ||

| ↓ T thymus, bone marrow | Deficiency promotes infection | Required for activity of > 100 enzymes | ||

| ↓ antioxidant enzyme activity | Repletion reduces morbidity, mortality | Required for zinc finger dependent transcription factors | ||

| Iron | T cells, monocytes | Deficiency affects T and NK cell development, ↓ neutrophil oxidative burst activity and ↓IgG4 | Anemia linked to HIV mortality | Promotes Th-2 response, ROS production |

| Iron excess causes infection in genetically susceptible host | Promotes bacterial growth; deficiency ↓IL-2 | |||

| ↑ HIV replication | Host polymorphisms and iron handling genes affect sequestration, pools; HFE gene regulates iron | |||

| Selenium | Monocytes, T cells, NK cells | Deficiency affects T and NK cell development | Improves survival in HIV infection | Antioxidant |

| Deficiency suppresses antigen presentation | May enhance maternal HIV transmission | Affects IL-2 response, regulates NF kappa B | ||

| Repletion ↑ T cell proliferation | May interact with viral genes | |||

| Vitamin A | T cells, NK cells, B cells | Promotes gut integrity | Deficiency ↑ infections and mortality from infections | Promotes Th-2 cytokine and IgA production |

| Deficiency ↓ NK activity | Levels depleted in infection | Inducer for gut-homing of T cells | ||

| Repletion improves gut integrity at weaning | Repletion ↑ recovery, reduces infection morbidity, mortality | IL-2 receptor beta, interferon regulatory factor, transcription factor mRNA Affects IL-12 and IL-10 production |

||

| Vitamin C | Phagocytes | Promotes phagocytic and NK activity | ↑ response to strep infection | Decreases monocyte response to LPS |

| Reduces stress IL-6 response | Reduces growth of H. pylori | Increases phagocytosis Increases NK activity |

||

| Vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3 | T cells, B cells, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells | Promotes gut integrity | Vitamin D deficiency promotes TB infection | Functions through a nuclear receptor, vitamin D receptor (VDR) which binds to response elements in target genes |

| Vitamin D3 affects differentiation, maturation, and function of cells | Affects differentiation of monocytes and dendritic cells | |||

| Vitamin D3 suppresses autoimmune disease in animal models | VDR polymorphisms regulate response to mycobacteria, hepatitis B, inflammatory bowel disease through TLR signaling | |||

| Vitamin E | T cells, B cells, monocytes | Maternal levels provide allergic protection | Deficiency may promote viral virulence | Modulates cyclic AMP response element binding proteins |

| T cell proliferation and IL-2 response ↑ in vitro | Affects prostaglandin production | |||

| Improves skin test response |

Zinc

Gestational zinc deficiency, caused by an imbalance between intake and increased requirement, is a common problem worldwide.55 Experimental models of zinc deficiency show a teratogenic effect on fetal development that also occurs due to “sequestration-induced deficiency” in individuals with borderline zinc status or an infection. Fetal malformations or loss have been observed in women with the genetic zinc deficiency, acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE), caused by an autosomal recessive defect of zinc absorption, who had inadequate, compensatory zinc intake during pregnancy; the loss or malformation of a fetus was also more common in mothers without AE who had low dietary intake.56 Circulating zinc levels decline during pregnancy due to hemodilution, decreased levels of zinc binding protein, hormonal changes, and the active transport of zinc from the mother to the fetus.56 While zinc status is difficult to assess accurately, the consensus is that deficiency is common in pregnancy, particularly in women consuming all-vegetarian diets with high levels of dietary phytate, which blocks zinc absorption. Neonatal zinc can be acquired through maternal milk. A recent study found that higher levels of expression of the CD4 T-cell receptor correlated with increased thymulin and zinc levels in healthy infants.53 While maternal defects in zinc transport into milk can be a cause of zinc deficiency in infants,57 premature infants have both a higher requirement and a reduced ability to conserve absorbed zinc.58 AE presents in infancy as skin lesions (acute dermatitis or hyperkeratotic plaques), diarrhea, alopecia, and is associated with increased incidence of infections caused by severe immune deficiency.59 Immune defects range from severe thymic atrophy and profound lymphopenia to skin test anergy and loss of NK cell activity. All symptoms resolve with adequate zinc supplementation. Zinc-fortified formulae improved linear growth in infants with protein calorie malnutrition and also improved delayed-type hypersensitivity, as shown by improved skin test reactivity, enhanced lymphoproliferative responses, and increased salivary IgA.60 Shah et al.56,61 reported that prenatal maternal zinc supplementation improved infants’ immune function and neurobehavioral development.

Animal model studies have demonstrated that perinatal zinc deficiency causes decreases in helper T-lymphocytes and NK cells and causes reduced cytokine responses that persist after zinc repletion.62 Zinc deficiency induces increased glucocorticoid production and reprogramming of the immune system at the level of bone marrow and is characterized by thymic atrophy, lymphopenia, and compromised cell- and antibody-mediated responses.63 Although few human studies have been performed, investigators have observed that antenatal zinc supplementation is beneficial for low-birth-weight-infant responses to BCG vaccination post birth, while zinc supplementation of infants after birth enhanced the response to one serotype of heptavalent pneumococcal protein conjugate vaccine.64,65

Iron

Iron deficiency anemia in children is associated with impaired immune response, as shown by reduced phagocytic activity and immunoglobulin levels.66 Prenatal stress in a nonhuman primate model led to iron-deficiency anemia and reduced NK cell activity in early infancy.24 Acute infection in iron-deficient children modulates proinflammatory cytokine responses and correlates with increased IL-6 and decreased IL-8 responses.67 Compared to adults, a lower level of CRP increase is associated with nutritional compromise in children, suggesting that the impact of infection on micronutrient balance is greater. Thus, among apparently healthy children at 1 year of age, CRP levels greater than 0.6 mg/L were associated with significantly reduced levels of transthyretin, iron, retinol, and beta-carotene.68 The relevance of iron status to post-natal immune development has been addressed in a few studies. Collins et al.69 demonstrated that experimental iron deficiency led to upregulation of apical iron transport-related proteins, transferrin receptor and heme oxygenase, and copper loading genes; it also decreased the expression of genes involved in the oxidative stress response.

Animals have developed various methods to sequester iron as a means of host defense. These methods are designed to deprive invading organisms of iron by depleting plasma during the acute-phase response; however, pathogens have simultaneously evolved systems to acquire iron even in highly iron-depleted environments. The anemia resulting from chronic disease is a contributing cause of faltering growth in children and is common in infants with congenital HIV infection.70 The controversy about iron supplementation has continued over several decades because of concern that excess, or inappropriate timing of, iron repletion would promote bacterial growth. The current consensus is that iron supplementation has a high probability of adversely affecting outcome in individuals who present with concurrent infection or who carry genes predisposing to iron overload.71–73 Studies of nutrient-gene interactions involving polymorphisms in haptaglobin, the hemoglobin-binding acute-phase protein, and the iron transporter NRAMP1 (natural-resistance-associated macrophage protein-1, or SLC11A1) have addressed the critical question of how iron affects the host response to HIV and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections.74 Both infections are characterized by altered iron handling75 and the interactions have greater potential effects in infancy.73,76

Selenium

Selenium is a critical component of the antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase, and it has independent antioxidant activity that is linked to decreased transcription and expression of manganese superoxide dismutase and uncoupling protein 2.77 Selenoproteins are an important component of the antioxidant host defense system affecting leukocyte and NK cell function. Selenium affects TLR signaling by inhibiting NF-kappa B activation by some agonists including LPS.78 Deficiency can be a critical component of protein calorie malnutrition and is associated with congestive heart failure in this setting. Juvenile cardiomyopathy (Keshan) appears to involve both selenium deficiency and enteroviral infection. Selenium and vitamin E deficiency can enhance the virulence of two RNA viruses, coxsackie B and influenza, through variant selection and possibly by direct effects on viral phenotype79; this could have important implications for human transmission.80 One experimental study suggests that selenium deficiency could be protective against influenza A in certain circumstances.81 Selenium may protect against cell death caused by some viral infections. Selenium supplementation in HIV infection enhances child survival without having direct effects on HIV progression.82,83 However, maternal selenium supplementation has been observed to enhance HIV viral shedding and may increase maternal infant transmission.84

Vitamin A

The value of vitamin A supplementation in the first few days of life for reducing early infant mortality from infections in populations with endemic vitamin A deficiency is well established.85,86 Vitamin A enhanced newborn immune response to hepatitis B vaccine and, when given in combination with zinc supplementation to children in Africa, it reduced the risk of fever and clinical episodes of malaria.87,88 Retinoic acid (RA), the vitamin A metabolite, is an inducer for the gut-homing specificity of T cells that enhances the expression of the integrin alpha4beta7 and CCR9 on T cells upon activation.89 Retinoic acid has also been shown to synergize with GALT-dendritic cell (DC) production of IL-6 or IL-5 and to induce IgA secretion.90 Current studies show that specific DCs in the GALT, which induce the development of Foxp3+Treg cells from CD4+ T cells, require the dietary metabolite retinoic acid (RA)91,92 and that RA directs Treg cell homing to the gut.93 Therefore, dietary vitamin A may be critical for the post-natal development of tolerance outside the thymus in response to antigen presentation under subimmunogenic conditions.94 Since impaired gut immune response in early infancy could contribute to the development of atopic sensitization, Pesonen et al. looked for an association between plasma retinol concentrations and the subsequent development of allergic symptoms in healthy infants. They found that retinol concentration at 2 months correlated inversely with a positive skin prick test at 5 and 20 years, and with allergic symptoms at 20 years.15 Others have shown that intestinal barrier function in mildly malnourished children was inversely correlated with serum retinol concentrations.21

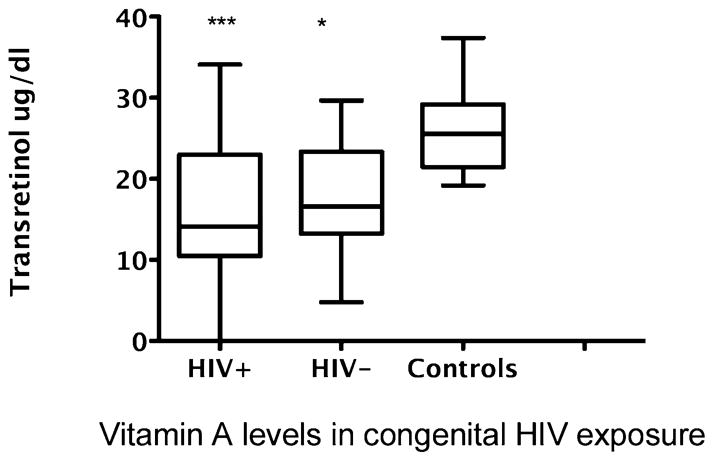

Vitamin A deficiency is associated with severity of many infections, including measles, rotavirus, HIV, and bacterial infections. Reduced levels of serum transretinol are common in infants of HIV-1-infected mothers,95,96 and this is independent of whether their own HIV status is positive. As shown in Figure 2, we found that the levels of transretinol were reduced in both seroreverters and in HIV-positive children in early life who were born to HIV-positive mothers compared to healthy children.96 Vitamin A deficiency, as measured by a low maternal serum retinol level, is a risk factor for mother-to-child transmission. Postpartum maternal and neonatal vitamin A supplementation of HIV-positive infants prolongs survival.97 However, the same supplementation regimen increased progression to death for breastfed children who were initially HIV negative and later infected through breast milk. Subsequent studies reported that mannose-binding lectin (MBL) gene polymorphisms have a regulatory effect on response to vitamin A in HIV infection. MBL is a component of the innate immune system that binds to carbohydrate ligands on the surface of many pathogens and activates the lectin pathway of the complement system. Persons with MBL-2 allele variants have deficiencies in innate immunity and have an increased susceptibility to HIV infection. Evaluation of infants receiving vitamin A plus beta-carotene A supplementation showed that the rates of maternal HIV transmission were higher in infants with MBL-2 variants in the control arm compared to the supplementation arm.98 Overall, the supplementation trials show that selective vitamin A supplementation of HIV-positive children prolongs their survival, but the trials do not provide evidence to recommend vitamin A supplementation of HIV-infected pregnant women.84

Figure 2. Vitamin A levels in congenital HIV exposure.

Data show comparison of serum transretinol levels in HIV-positive children (n = 13; mean age 2.2 ± 2.0 years) compared to seroreverter children (n = 9; mean age 1.1 ± 1.2 years) and control healthy children (n = 23; mean age 2.3 ± 1.6 years). Differences in vitamin A levels compared to controls were significant by one-way analysis of variance (P = 0.0003) and pairwise differences using Tukey’s multiple comparison test between HIV-positive versus controls and HIV-negative serorevertors compared to controls were significant (P < 0.05).

Vitamin C

Dietary vitamin C intake is specifically associated with preterm birth via premature rupture of membranes, and it may be linked to genetic variants in the vitamin C transporters by enhancing risk of spontaneous preterm birth.99 Vitamin C is a free radical scavenger that serves as an important antioxidant. Vitamin C concentrations in the plasma and leukocytes decline during infections and stress. Supplementation with antioxidant vitamins, including vitamin C, has been shown to improve immune response to group A streptococcal infection in children compared to penicillin alone.100 Supplementation may enhance phagocytosis and NK cell activity101 by increasing levels of the antioxidant plasma glutathione levels. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with a decrease in gastric juice ascorbic acid concentration, and this effect is greater in children with the CagA-positive strain A.102 Vitamin C has antimicrobial effects against H. pylori.103 Children are susceptible to H. pylori infection through household contact, and infection is associated with increased incidence of gastric reflux104 in childhood and lifetime risk of gastric cancer.

Vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3]

The critical role of vitamin D as a regulator of calcium homeostasis in growing children and the impact of vitamin D deficiency on bone mineral density due to inadequate sun exposure or obesity is emerging as a serious health problem. Experimental vitamin D deficiency promotes the development of autoimmune disease including inflammatory bowel disease and is blocked by the active form of vitamin D.105 This discovery has led to the hypothesis that vitamin D is an environmental factor that affects the development of immune-mediated diseases.106 Other studies showed that inflammation in the IL-10 knockout mouse could be suppressed by 1,25(OH)2D3. This therapeutic effect was maximized by the addition of high levels of calcium. Overall, blockade of inflammation involved inhibition of the TNF-alpha pathway.107 Relevant studies in humans suggest that vitamin D receptor variants are linked to the development of asthma and atopic disease.108 Vitamin D deficiency in children with nutritional rickets is associated with increased infections.109 Allelic variants of the vitamin D receptor appear to mediate differential susceptibility of children to M. tuberculosis infection110 and to acute lower respiratory infections.111 In the case of mycobacterial infection, the mechanism of effect involves TLR activation of human macrophages, upregulated expression of the vitamin D receptor and the vitamin D-1-hydroxylase genes, leading to induction of the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin and intracellular killing of M. tuberculosis.112

Vitamin E

Vitamin E is a strong antioxidant that enhances monocyte/macrophage-mediated response. Emerging studies suggest improvement in eczema and reduced serum levels of immunoglobulin E in atopic subjects with dermatitis treated with vitamin E.113 Current studies, as noted above, suggest that vitamin E deficiency may enhance the virulence of viral infections through effects on the virus.114

Beta Glucan

The neonatal innate immune system provides the initial line of defense against microbial infections through recognition and response to a wide range of microorganisms, and it is based on a germ-line encoded repertoire of invariant TLR receptors. The requirement for post-birth maturation of this system under the influence of dietary factors, including soluble forms of TLRs present in human milk, is now appreciated.115 The development of the adaptive immune response post birth initially requires maturation of the innate immune system and, in the absence of such contacts, as formulated in the “hygiene” hypothesis, asthma, allergies, and atopic and autoimmune diseases are more likely to develop in susceptible individuals. Antigen dose affects response and may define the outcome of sensitization. Th-2 (allergic) priming is preferentially favored by low-dose antigen exposure, whereas higher doses favor Th-1 priming. Therefore, enhanced exposure to endotoxin and other microbial components is considered the important protective factor that is prevalent in farm environments. Assessment of the levels and determinants of bacterial endotoxin or LPS, mould beta(1,3)-glucans, and fungal extracellular polysaccharides in the house dust from environments of exposed and reference children recently showed that the levels per gram of house dust in farm homes were 1.2- to 3.2-fold higher than the levels in reference homes.116

Beta 1, 3 D-glucan is a cell-wall component found in several fungal pathogens, including Candida and Aspergillus spp., but also in mushrooms and barley. Children have been shown to have higher levels of beta glucan in blood compared to adults.117 Iossifova et al. examined the association between (1-3)-beta-D-glucan exposure and the prevalence of allergen sensitization and wheezing during the first year of life in a large birth cohort of infants born to atopic parents. The results showed that high exposure to beta glucan, but not to endotoxin, was associated with decreased risk of recurrent wheezing among infants born to atopic parents. This effect was more pronounced in the subgroup of allergen-sensitized infants.118

Glucans are hematopoietic and immune system activators. We studied the effects of an extract from the Maitake mushroom beta glucan (MBG), on the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells in the mouse and in human umbilical cord blood. We found that MBG enhanced murine bone marrow cell proliferation and differentiation into granulocyte-monocyte colony forming unit (CFU-GM) in a dose-dependent manner.119 MBG enhanced cord blood stem cell proliferation and differentiation into CFU-GM in vitro in a dose-dependent manner. MBG induced granulocyte colony stimulating factor production in cord blood but not in adult monocytes.120 This difference could reflect the early stage of development of the cord blood monocyte compared to the adult monocyte or may suggest that adults are less responsive to beta glucans due to tolerance induction.

Experimental studies have shown that orally administered water-soluble glucans translocate from the gastrointestinal tract into the systemic circulation. The glucans are bound by gut epithelial and GALT cells, and they modulate the expression of pattern recognition receptors in the GALT, increase IL-12 expression, and induce protection against infectious challenge with Staphylococcus aureus or Candida albicans.121

In addition to their presence in the environment, beta glucans are found in human milk122 and are being introduced into the food supply in yogurts and oat milk.123,124 Therefore, the potential effect of beta glucans in modulating neonatal immune response may provide another approach to enhancing host defense in early life.

CONCLUSION

In summary, nutrients exert unique regulatory effects in the perinatal period that mold the developing immune system. The interactions of micronutrients as well as microbial and environmental antigens condition the post-birth maturation of the immune system, thereby influencing reactions to allergens, fostering tolerance towards the emerging gastrointestinal flora and ingested antigens, and defining patterns of host defense against potential pathogens.

Acknowledgments

Funding. This work was supported in part by NIH NCI CA 29502, NIH NCRR M01 RR 6020, M01RR0004, UL1 RR024996, NIH NCI R25 105012, NIH NCCAM, and ODS: 1-P50-AT02779, and The Children’s Cancer and Blood Foundation.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

Contributor Information

Susanna Cunningham-Rundles, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Host Defenses Program, Department of Pediatrics, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, New York, USA.

Hong Lin, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Host Defenses Program, Department of Pediatrics, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, New York, USA.

Deborah Ho-Lin, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Host Defenses Program, Department of Pediatrics, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, New York, USA.

Ann Dnistrian, Department of Clinical Laboratories, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

Barrie R Cassileth, Integrative Medicine Service, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

Jeffrey M Perlman, Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, New York, USA.

References

- 1.Walker WA. Role of nutrients and bacterial colonization in the development of intestinal host defense. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30(Suppl):S2–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulligan P, White NR, Monteleone G, et al. Breast milk lactoferrin regulates gene expression by binding bacterial DNA CpG motifs but not genomic DNA promoters in model intestinal cells. Pediatr Res. 2006;59:656–661. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000214958.80011.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forchielli ML, Walker WA. The role of gut-associated lymphoid tissues and mucosal defence. Br J Nutr. 2005;93 (Suppl):S41–S48. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham-Rundles S, McNeeley DF, Moon A. Mechanisms of nutrient modulation of the immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.04.036. quiz 1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palinski W, Yamashita T, Freigang S, Napoli C. Developmental programming: maternal hypercholesterolemia and immunity influence susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Nutr Rev. 2007;65(Suppl):S182–S187. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Thornburg KL, Kajantie E, Forsen TJ, Eriksson JG. A possible link between the pubertal growth of girls and breast cancer in their daughters. Am J Hum Biol. 2008;20:127–131. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plagemann A. Perinatal nutrition and hormone-dependent programming of food intake. Horm Res. 2006;65:83–89. doi: 10.1159/000091511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDade TW, Beck MA, Kuzawa C, Adair LS. Prenatal undernutrition, postnatal environments, and antibody response to vaccination in adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:543–548. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore SE, Collinson AC, Tamba N’Gom P, Aspinall R, Prentice AM. Early immunological development and mortality from infectious disease in later life. Proc Nutr Soc. 2006;65:311–318. doi: 10.1079/pns2006503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson AA. Nutrients, growth, and the development of programmed metabolic function. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;478:41–55. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46830-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tantisira KG, Weiss ST. Childhood infections and asthma: at the crossroads of the hygiene and Barker hypotheses. Respir Res. 2001;2:324–327. doi: 10.1186/rr81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young LE. Imprinting of genes and the Barker hypothesis. Twin Res. 2001;4:307–317. doi: 10.1375/1369052012632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vassallo MF, Walker WA. Neonatal microbial flora and disease outcome. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program. 2008;61:211–224. doi: 10.1159/000113496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeBouder E, Rey-Nores JE, Raby AC, et al. Modulation of neonatal microbial recognition: TLR-mediated innate immune responses are specifically and differentially modulated by human milk. J Immunol. 2006;176:3742–3752. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pesonen M, Kallio MJ, Siimes MA, Ranki A. Retinol concentrations after birth are inversely associated with atopic manifestations in children and young adults. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunningham-Rundles S, Moon A, McNeeley D. Malnutrition and host defense. In: Duggan C, Watkins JB, Walker WA, editors. Nutrition in Pediatrics: Basic Science and Clinical Application. 4. London: BC Decker, Hamilton; 2008. pp. 261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mora JR. Homing imprinting and immunomodulation in the gut: role of dendritic cells and retinoids. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;4:275–289. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marodi L. Innate cellular immune responses in newborns. Clin Immunol. 2006;118:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field CJ, Van Aerde JE, Robinson LE, Clandinin MT. Effect of providing a formula supplemented with long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on immunity in full-term neonates. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:91–99. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507791845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauritzen L, Kjaer TM, Fruekilde MB, Michaelsen KF, Frokiaer H. Fish oil supplementation of lactating mothers affects cytokine production in 2 1/2-year-old children. Lipids. 2005;40:669–676. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quadro L, Gamble MV, Vogel S, et al. Retinol and retinol-binding protein: gut integrity and circulating immunoglobulins. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(Suppl 1):S97–S102. doi: 10.1086/315920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wayse V, Yousafzai A, Mogale K, Filteau S. Association of subclinical vitamin D deficiency with severe acute lower respiratory infection in Indian children under 5 y. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:563–567. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dylewski ML, Mastro AM, Picciano MF. Maternal selenium nutrition and neonatal immune system development. Biol Neonate. 2002;82:122–127. doi: 10.1159/000063088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coe CL, Lubach GR, Shirtcliff EA. Maternal stress during pregnancy predisposes for iron deficiency in infant monkeys impacting innate immunity. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:520–524. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e318045be53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devereux G, Barker RN, Seaton A. Antenatal determinants of neonatal immune responses to allergens. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:43–50. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-0477.2001.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman MJ, Sarker P, Roy SK, et al. Effects of zinc supplementation as adjunct therapy on the systemic immune responses in shigellosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:495–502. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.81.2.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long KZ, Santos JI, Rosado JL, et al. Impact of vitamin A on selected gastrointestinal pathogen infections and associated diarrheal episodes among children in Mexico City, Mexico. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1217–1225. doi: 10.1086/508292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green AE, Lissina A, Hutchinson SL, et al. Recognition of nonpeptide antigens by human V gamma 9V delta 2 T cells requires contact with cells of human origin. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:472–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02472.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barker DJ. The developmental origins of chronic adult disease. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2004;93:26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDade TW, Beck MA, Kuzawa CW, Adair LS. Prenatal undernutrition and postnatal growth are associated with adolescent thymic function. J Nutr. 2001;131:1225–1231. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore DC, Elsas PX, Maximiano ES, Elsas MI. Impact of diet on the immunological microenvironment of the pregnant uterus and its relationship to allergic disease in the offspring – a review of the recent literature. Sao Paulo Med J. 2006;124:298–303. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802006000500013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merlot E, Couret D, Otten W. Prenatal stress, fetal imprinting and immunity. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gotz AA, Wittlinger S, Stefanski V. Maternal social stress during pregnancy alters immune function and immune cell numbers in adult male Long-Evans rat offspring during stressful life-events. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;185:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Precht DH, Andersen PK, Olsen J. Severe life events and impaired fetal growth: a nation-wide study with complete follow-up. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:266–275. doi: 10.1080/00016340601088406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Entringer S, Kumsta R, Nelson EL, Hellhammer DH, Wadhwa PD, Wust S. Influence of prenatal psychosocial stress on cytokine production in adult women. Dev Psychobiol. 2008;50:579–587. doi: 10.1002/dev.20316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langdown ML, Sugden MC. Enhanced placental GLUT1 and GLUT3 expression in dexamethasone-induced fetal growth retardation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;185:109–117. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vieau D, Sebaai N, Leonhardt M, et al. HPA axis programming by maternal undernutrition in the male rat offspring. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(Suppl 1):S16–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manary MJ, Muglia LJ, Vogt SK, Yarasheski KE. Cortisol and its action on the glucocorticoid receptor in malnutrition and acute infection. Metabolism. 2006;55:550–554. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prasad AS, Meftah S, Abdallah J, et al. Serum thymulin in human zinc deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:1202–1210. doi: 10.1172/JCI113717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jambon B, Ziegler O, Maire B, et al. Thymulin (facteur thymique serique) and zinc contents of the thymus glands of malnourished children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;48:335–342. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savino W, Dardenne M, Velloso LA, Dayse Silva-Barbosa S. The thymus is a common target in malnutrition and infection. Br J Nutr. 2007;98(Suppl 1):S11–S16. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507832880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cunningham-Rundles S, McNeely D, Ananworanich JM. Immune response in malnutrition. In: Stiehm ER, Ochs HD, Winkelstein JA, editors. Immunologic Disorders in Infants and Children. 5. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2004. pp. 761–784. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beisel WR. Infection-induced depression of serum retinol – a component of the acute phase response or a consequence? Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:993–994. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dulger H, Arik M, Sekeroglu MR, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokines in Turkish children with protein-energy malnutrition. Mediators Inflamm. 2002;11:363–365. doi: 10.1080/0962935021000051566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fischer Walker CL, Black RE. Functional indicators for assessing zinc deficiency. Food Nutr Bull. 2007;28(Suppl):S454–S479. doi: 10.1177/15648265070283s305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shalak LF, Laptook AR, Jafri HS, Ramilo O, Perlman JM. Clinical chorioamnionitis, elevated cytokines, and brain injury in term infants. Pediatrics. 2002;110:673–680. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez L, Gonzalez C, Flores L, et al. Assessment by flow cytometry of cytokine production in malnourished children. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:502–507. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.4.502-507.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schultz C, Strunk T, Temming P, Matzke N, Hartel C. Reduced IL-10 production and -receptor expression in neonatal T lymphocytes. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:1122–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohamed MA, Cunningham-Rundles S, Dean CR, Hammad TA, Nesin M. Levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines produced from cord blood in-vitro are pathogen dependent and increased in comparison to adult controls. Cytokine. 2007;39:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tatad AM, Nesin M, Peoples J, et al. Cytokine expression in response to bacterial antigens in preterm and term infant cord blood monocytes. Neonatology. 2007;94:8–15. doi: 10.1159/000112541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haynes BF, Markert ML, Sempowski GD, Patel DD, Hale LP. The role of the thymus in immune reconstitution in aging, bone marrow transplantation, and HIV-1 infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:529–560. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mocchegiani E, Santarelli L, Costarelli L, et al. Plasticity of neuroendocrine-thymus interactions during ontogeny and ageing: role of zinc and arginine. Ageing Res Rev. 2006;5:281–309. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meazza C, Mocchegiani E, Pagani S, Travaglino P, Bozzola M. Relationship between thymulin and growth hormone secretion in healthy human neonates. Am J Perinatol. 2007;24:227–233. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cunningham-Rundles S, Ho Lin D. Malnutrition and infection in industrialized countries. In: Schroten H, Wirth SK, editors. Pediatric Infectious Disease Revisited. Birkhauser Advances in Infectious Disease. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhauser; 2007. pp. 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wellinghausen N. Immunobiology of gestational zinc deficiency. Br J Nutr. 2001;85(Suppl 2):S81–S86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shah D, Sachdev HP. Zinc deficiency in pregnancy and fetal outcome. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:15–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2006.tb00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stevens J, Lubitz L. Symptomatic zinc deficiency in breast-fed term and premature infants. J Paediatr Child Health. 1998;34:97–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1998.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hambidge KM, Krebs NF, Westcott JE, Miller LV. Changes in zinc absorption during development. J Pediatr. 2006;149(Suppl 5):S64–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moynahan EJ. Letter: acrodermatitis enteropathica: a lethal inherited human zinc-deficiency disorder. Lancet. 1974;2:399–400. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91772-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schlesinger L, Arevalo M, Arredondo S, Diaz M, Lonnerdal B, Stekel A. Effect of a zinc-fortified formula on immunocompetence and growth of malnourished infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:491–498. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shah D, Sachdev HP. Effect of gestational zinc deficiency on pregnancy outcomes: summary of observation studies and zinc supplementation trials. Br J Nutr. 2001;85(Suppl 2):S101–S108. doi: 10.1079/bjn2000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beach RS, Gershwin ME, Hurley LS. Persistent immunological consequences of gestation zinc deprivation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983;38:579–590. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/38.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fraker PJ, King LE. Reprogramming of the immune system during zinc deficiency. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:277–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Osendarp SJ, Prabhakar H, Fuchs GJ, et al. Immunization with the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Bangladeshi infants and effects of zinc supplementation. Vaccine. 2007;25:3347–3354. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Osendarp SJ, Fuchs GJ, van Raaij JM, et al. The effect of zinc supplementation during pregnancy on immune response to Hib and BCG vaccines in Bangladesh. J Trop Pediatr. 2006;52:316–323. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fml012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ekiz C, Agaoglu L, Karakas Z, Gurel N, Yalcin I. The effect of iron deficiency anemia on the function of the immune system. Hematol J. 2005;5:579–583. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jason J, Archibald LK, Nwanyanwu OC, et al. The effects of iron deficiency on lymphocyte cytokine production and activation: preservation of hepatic iron but not at all cost. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;126:466–473. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abraham K, Muller C, Gruters A, Wahn U, Schweigert FJ. Minimal inflammation, acute phase response and avoidance of misclassification of vitamin A and iron status in infants – importance of a high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) assay. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2003;73:423–430. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.73.6.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Collins JF, Franck CA, Kowdley KV, Ghishan FK. Identification of differentially expressed genes in response to dietary iron deprivation in rat duodenum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G964–G971. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00489.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Totin D, Ndugwa C, Mmiro F, Perry RT, Jackson JB, Semba RD. Iron deficiency anemia is highly prevalent among human immunodeficiency virus-infected and uninfected infants in Uganda. J Nutr. 2002;132:423–429. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chung BH, Ha SY, Chan GC, et al. Klebsiella infection in patients with thalassemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:575–579. doi: 10.1086/367656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cunningham-Rundles S, Giardina PJ, Grady RW, Califano C, McKenzie P, De Sousa M. Effect of transfusional iron overload on immune response. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(Suppl 1):S115–S121. doi: 10.1086/315919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iannotti LL, Tielsch JM, Black MM, Black RE. Iron supplementation in early childhood: health benefits and risks. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1261–1276. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.6.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McDermid JM, Prentice AM. Iron and infection: effects of host iron status and the iron-regulatory genes haptoglobin and NRAMP1 (SLC11A1) on host-pathogen interactions in tuberculosis and HIV. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110:503–524. doi: 10.1042/CS20050273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cunningham-Rundles S. Trace elements and minerals. HIV infection and AIDS: implications for host defense. In: Bogden JD, Kelvay LM, editors. The Clinical Nutrition of the Essential Trace Elements and Minerals. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2000. pp. 333–351. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miller MF, Stoltzfus RJ, Mbuya NV, Malaba LC, Iliff PJ, Humphrey JH. Total body iron in HIV-positive and HIV-negative Zimbabwean newborns strongly predicts anemia throughout infancy and is predicted by maternal hemoglobin concentration. J Nutr. 2003;133:3461–3468. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shilo S, Aharoni-Simon M, Tirosh O. Selenium attenuates expression of MnSOD and uncoupling protein 2 in J774.2 macrophages: molecular mechanism for its cell-death and antiinflammatory activity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:276–286. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Youn HS, Lim HJ, Choi YJ, Lee JY, Lee MY, Ryu JH. Selenium suppresses the activation of transcription factor NF-kappa B and IRF3 induced by TLR3 or TLR4 agonists. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Beck MA, Levander OA, Handy J. Selenium deficiency and viral infection. J Nutr. 2003;133(Suppl):S1463–S1467. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1463S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Louria DB. Undernutrition can affect the invading microorganism. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:470–474. doi: 10.1086/520026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li W, Beck MA. Selenium deficiency induced an altered immune response and increased survival following influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 infection. Exp Biol Med (Marywood) 2007;232:412–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Verma S, Molina Y, Lo YY, et al. In vitro effects of selenium deficiency on West Nile virus replication and cytopathogenicity. Virol J. 2008;5:66. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kupka R, Mugusi F, Aboud S, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of selenium supplements among HIV-infected pregnant women in Tanzania: effects on maternal and child outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1802–1808. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mehta S, Fawzi W. Effects of vitamins, including vitamin A, on HIV/AIDS patients. Vitam Horm. 2007;75:355–383. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(06)75013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fawzi WW, Chalmers TC, Herrera MG, Mosteller F. Vitamin A supplementation and child mortality. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1993;269:898–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tielsch JM, Rahmathullah L, Thulasiraj RD, et al. Newborn vitamin A dosing reduces the case fatality but not incidence of common childhood morbidities in South India. J Nutr. 2007;137:2470–2474. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Newton S, Owusu-Agyei S, Ampofo W, et al. Vitamin A supplementation enhances infants’ immune responses to hepatitis B vaccine but does not affect responses to Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine. J Nutr. 2007;137:1272–1277. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.5.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zeba AN, Sorgho H, Rouamba N, et al. Major reduction of malaria morbidity with combined vitamin A and zinc supplementation in young children in Burkina Faso: a randomized double blind trial. Nutr J. 2008;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Iwata M, Hirakiyama A, Eshima Y, Kagechika H, Kato C, Song SY. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mora JR, Iwata M, Eksteen B, et al. Generation of gut-homing IgA-secreting B cells by intestinal dendritic cells. Science. 2006;314:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1132742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via aTGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sun CM, Hall JA, Blank RB, et al. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Benson MJ, Pino-Lagos K, Rosemblatt M, Noelle RJ. All-trans retinoic acid mediates enhanced T reg cell growth, differentiation, and gut homing in the face of high levels of co-stimulation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1765–1774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.von Boehmer H. Oral tolerance: is it all retinoic acid? J Exp Med. 2007;204:1737–1739. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dreyfuss ML, Fawzi WW. Micronutrients and vertical transmission of HIV-1. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:959–970. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cunningham-Rundles S, Ahrn S, Abuav-Nussbaum R, Dnistrian A. Development of immunocompetence: role of micronutrients and microorganisms. Nutr Rev. 2002;60(Suppl):S68–S72. doi: 10.1301/00296640260130777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Humphrey JH, Iliff PJ, Marinda ET, et al. Effects of a single large dose of vitamin A, given during the postpartum period to HIV-positive women and their infants, on child HIV infection, HIV-free survival, and mortality. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:860–871. doi: 10.1086/500366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kuhn L, Coutsoudis A, Trabattoni D, et al. Synergy between mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphisms and supplementation with vitamin A influences susceptibility to HIV infection in infants born to HIV-positive mothers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:610–615. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Erichsen HC, Engel SA, Eck PK, et al. Genetic variation in the sodium-dependent vitamin C transporters. SLC23A1, and SLC23A2 and risk for preterm delivery. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:245–254. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ahmed J, Zaman MM, Ali SM. Immunological response to antioxidant vitamin supplementation in rural Bangladeshi school children with group A streptococcal infection. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2004;13:226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wintergerst ES, Maggini S, Hornig DH. Immune-enhancing role of vitamin C and zinc and effect on clinical conditions. Ann Nutr Metab. 2006;50:85–94. doi: 10.1159/000090495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Baysoy G, Ertem D, Ademoglu E, Kotiloglu E, Keskin S, Pehlivanoglu E. Gastric histopathology, iron status and iron deficiency anemia in children with Helicobacter pylori infection. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:146–151. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200402000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Akyon Y. Effect of antioxidants on the immune response of Helicobacter pylori. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2002;8:438–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2002.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Moon A, Solomon A, Beneck D, Cunningham-Rundles S. Positive association between Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:283–288. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31818eb8de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. Mounting evidence for vitamin D as an environmental factor affecting autoimmune disease prevalence. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:1136–1142. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cantorna MT, Yu S, Bruce D. The paradoxical effects of vitamin D on type 1 mediated immunity. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhu Y, Mahon BD, Froicu M, Cantorna MT. Calcium and 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 target the TNF-alpha pathway to suppress experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:217–224. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Poon AH, Laprise C, Lemire M, et al. Association of vitamin D receptor genetic variants with susceptibility to asthma and atopy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:967–973. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200403-412OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yener E, Coker C, Cura A, Keskinoglu A, Mir S. Lymphocyte subpopulations in children with vitamin D deficient rickets. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1995;37:500–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1995.tb03362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hill AV. The immunogenetics of human infectious diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:593–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Roth DE, Jones AB, Prosser C, Robinson JL, Vohra S. Vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and the risk of acute lower respiratory tract infection in early childhood. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:676–680. doi: 10.1086/527488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tsoureli-Nikita E, Hercogova J, Lotti T, Menchini G. Evaluation of dietary intake of vitamin E in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a study of the clinical course and evaluation of the immunoglobulin E serum levels. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:146–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Beck MA, Handy J, Levander OA. Host nutritional status: the neglected virulence factor. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.LeBouder E, Rey-Nores JE, Rushmere NK, et al. Soluble forms of Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 capable of modulating TLR2 signaling are present in human plasma and breast milk. J Immunol. 2003;171:6680–6689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gehring U, Heinrich J, Hoek G, et al. Bacteria and mould components in house dust and children’s allergic sensitization. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:1144–1153. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00118806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Smith PB, Benjamin DK, Jr, Alexander BD, Johnson MD, Finkelman MA, Steinbach WJ. Quantification of 1,3-beta-D-glucan levels in children: preliminary data for diagnostic use of the beta-glucan assay in a pediatric setting. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:924–925. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00025-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Iossifova YY, Reponen T, Bernstein DI, et al. House dust (1-3)-beta-D-glucan and wheezing in infants. Allergy. 2007;62:504–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lin H, She YH, Cassileth BR, Sirotnak F, Cunningham Rundles S. Maitake beta-glucan MD-fraction enhances bone marrow colony formation and reduces doxorubicin toxicity in vitro. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lin H, Cheung SWY, Nesin M, Cassileth BR, Cunningham-Rundles S. Enhancement of umbilical cord blood cell hematopoiesis by Maitake beta glucan is mediated by G-CSF production. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:21–27. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00284-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rice PJ, Adams EL, Ozment-Skelton T, et al. Oral delivery and gastrointestinal absorption of soluble glucans stimulate increased resistance to infectious challenge. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1079–1086. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kondori N, Edebo L, Mattsby-Baltzer I. Circulating beta (1-3) glucan and immunoglobulin G subclass antibodies to Candida albicans cell wall antigens in patients with systemic candidiasis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:344–350. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.2.344-350.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Vasiljevic T, Kealy T, Mishra VK. Effects of beta-glucan addition to a probiotic containing yogurt. J Food Sci. 2007;72:C405–C411. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Onning G, Akesson B, Oste R, Lundquist I. Effects of consumption of oat milk, soya milk, or cow’s milk on plasma lipids and antioxidative capacity in healthy subjects. Ann Nutr Metab. 1998;42:211–220. doi: 10.1159/000012736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]