Abstract

Background

To investigate whether the response to induction chemotherapy (IC) would impact the timing of thoracic radiotherapy (TRT) in limited-stage small-cell lung cancer (LS-SCLC).

Methods

A total of 146 patients with LS-SCLC who had received two to six cycles of IC followed by TRT from January 2009 to December 2011 at our hospital were included in this study. Patients were divided into two groups based on the time TRT was administered: early TRT (administered after 2–3 cycles of chemotherapy) or late TRT (administered after 4–6 cycles). Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to evaluate the independent factors affecting survival.

Results

The median OS for patients who received early TRT and late TRT was 29.0 and 19.9 months, respectively, (P = 0.018) and the median PFS was 18.5 and 13.8 months, respectively (P = 0.049). In patients who achieved complete remission (CR) or partial remission (PR) after two to three cycles of IC, the median OS was 36.1 and 22.5 months in the early and late TRT subgroups, respectively (P = 0.009); the corresponding median PFS was 20.2 and 13.8 months, respectively (P = 0.038). In the patients who did not achieve CR or PR, no statistic difference was found in OS or PFS between the two subgroups.

Conclusion

Patients who received early TRT had more favorable outcomes than those who received late TRT. Patients who achieved CR or PR after two to three cycles of IC obtained more benefit from early TRT.

Keywords: Induction chemotherapy, radiotherapy, small cell lung carcinoma

Introduction

Over the past two decades, the greatest advances in first-line treatment for SCLC have been in the field of radiation oncology. Concurrent thoracic radiotherapy (TRT) with cisplatin-based chemotherapy is considered the standard of care for patients with limited-stage, small-cell lung cancer (LS-SCLC).1 However, controversy remains regarding the radiation dose and fraction, the radiation target, and the optimal timing of chemoradiotherapy.2 Several randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses focused on the timing of TRT have provided supportive evidence that the early administration of TRT in combination with chemotherapy improves survival in LS-SCLC,3–8 and the 2014 National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network (NCCN) guidelines for SCLC state that category 1 evidence exists to support the commencement of radiotherapy in combination with the first or second cycle of chemotherapy. However, early concurrent radiotherapy and dose-intense therapy are not appropriate for all patients because of practical limitations. It has been reported that less than 69% of patients who receive TRT concurrently with the first cycle of chemotherapy completed the planned chemotherapy regimen.9 Delayed initiation of TRT is a preferable choice when patients present with poor performance status or severe comorbidities, or when patients have bulky tumors that require large radiation target volumes, which inevitably increase toxic effects or result in an unacceptable dose to normal tissue. Two to three cycles of induction chemotherapy (IC) allow for an evaluation of the response to the chemotherapy regimen, relieve toxic effects as a result of tumor volume shrinkage, and avoid probable treatment delays related to preparation for TRT. A phase III trial conducted in Korea demonstrated that late TRT administered with the third cycle of etoposide and cisplatin (EP) chemotherapy was not inferior to early TRT in the treatment of LS-SCLC.10 This result led to attempts to clarify whether more cycles of chemotherapy, which further delay TRT, are an alternative choice for patients who have a good response to IC. Although 60–80% of patients with SCLC potentially respond to the classic EP regimen, many patients are not sensitive to chemotherapy.11 We, therefore, intended to evaluate whether different responses to the first two to three cycles of chemotherapy can influence the decision-making process with regard to the timing of TRT, thereby aiding treatment decisions.

Methods and materials

Criteria for the inclusion of clinical data

The criteria for the inclusion of clinical data were as follows: (i) patients were treated at our institution between January 2009 and December 2011; (ii) SCLC was confirmed by cytology, histology, or both; (iii) the disease was clinically diagnosed as LS-SCLC according to the Veterans Administration Lung Study Group classification system (and reclassified by the 2009 Union for International Cancer Control staging system); (iv) all patients received two to six cycles of IC, followed by definitive TRT with or without concurrent chemotherapy and maintenance chemotherapy; and (v) therapeutic responses after two to three cycles of chemotherapy were estimated with computed tomography (CT) scans based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (version 1.1) as complete remission (CR, no evidence of tumor and lymph node of <10 mm on the short axis; confirmed at 4 weeks), partial remission (PR, at least a 30% decrease in the sum of the diameters of the target lesions, taking as reference the baseline sum diameters; confirmed at 4 weeks), stable disease (SD, neither PR nor PD criteria met), and partial disease (PD, at least a 20% increase in the sum of the diameters of the target lesions, taking as reference the smallest sum of the study [including the baseline sum if this is the smallest] and demonstrate an absolute increase of at least 5 mm; the appearance of new lesions is also considered).

Patient characteristics

A total of 154 eligible patients with LS-SCLC were initially enrolled. We excluded eight patients because of incomplete data. The patients were divided into two groups: early TRT (TRT administered after 2–3 cycles of chemotherapy) or late TRT (TRT administered after 4–6 cycles of chemotherapy). Eighty-nine patients received early TRT, and 57 received late TRT. The characteristics of the remaining 146 patients are summarized in Table 1, and the distribution of basic characteristics and treatment approaches in the early and late TRT groups are shown in Table2.

Table 1.

Patient clinical data and survival-related factors

| Variables | N | Overall survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (m) | 1-year (%) | 2-year (%) | 3-year (%) | x2 | P | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 103 | 26.2 | 86.4 | 53.4 | 35.4 | 0.157 | 0.692 |

| Female | 43 | 22.8 | 86.0 | 48.8 | 41.1 | ||

| Age | |||||||

| ≤60 | 90 | 29.0 | 90.0 | 58.8 | 44.4 | 5.016 | 0.024 |

| >60 | 56 | 19.4 | 81.8 | 43.9 | 27.9 | ||

| Smoking | |||||||

| Yes | 102 | 25.4 | 85.3 | 52.0 | 34.7 | 1.370 | 0.242 |

| No | 44 | 24.9 | 88.6 | 52.3 | 42.3 | ||

| TNM stage | |||||||

| I | 5 | — | 100 | 80.0 | 60.0 | ||

| II | 14 | 37.8 | 92.9 | 71.4 | 57.1 | 4.071 | 0.254 |

| III a | 90 | 22.5 | 85.6 | 47.8 | 34.7 | ||

| III b | 37 | 25.4 | 83.8 | 51.4 | 31.9 | ||

| Response to 2–3 cycles of induction chemotherapy | |||||||

| CR/PR | 114 | 28.4 | 88.6 | 54.4 | 40.6 | 5.299 | 0.021 |

| PD/SD | 32 | 17.8 | 78.1 | 43.8 | 24.3 | ||

| Prophylactic brain irradiation | |||||||

| Yes | 52 | 36.1 | 94.2 | 67.3 | 51.0 | 10.15 | 0.001 |

| No | 94 | 19.4 | 81.9 | 43.6 | 29.2 | ||

| Time of radiotherapy | |||||||

| Early | 89 | 29.0 | 87.6 | 57.3 | 44.0 | 5.042 | 0.018 |

| Late | 57 | 19.9 | 84.2 | 43.9 | 26.3 | ||

| Concurrent chemotherapy | |||||||

| Yes | 45 | 24.9 | 86.7 | 53.3 | 44.1 | 0.974 | 0.324 |

| No | 101 | 28.4 | 86.1 | 51.5 | 34.0 | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||||||

| Yes | 96 | 28.4 | 89.6 | 55.2 | 39.3 | 3063 | 0.080 |

| No | 50 | 19.4 | 80.0 | 46.0 | 32.7 | ||

| GTV (cm3) | |||||||

| Median | 31.52 | 0.006* | |||||

| Range | 0–422.3 | ||||||

P values were obtained based on the Cox proportional hazard model. CR, complete remission; GTV, gross target volume; PD, partial disease; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; TNM, tumor node metastasis.

Table 2.

Clinical data of patients in the early and late TRT groups

| Time of TRT | Early TRT | Late TRT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (n = 89) | (n = 57) | χ2 | P |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 60 (67.4%) | 43 (75.4%) | 1.076 | 0.354 |

| Female | 29 (32.6%) | 14 (24.6%) | ||

| Age | ||||

| ≤60 | 57 (64.0%) | 33 (57.9%) | 0.566 | 0.489 |

| >60 | 32 (36.0%) | 24 (42.1%) | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Yes | 30 (33.7%) | 28 (49.1%) | 3.448 | 0.083 |

| No | 59 (66.3%) | 29 (50.9%) | ||

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 58 (65.2%) | 44 (77.2%) | 2.386 | 0.142 |

| No | 31 (34.8%) | 13 (22.8%) | ||

| Stage | ||||

| Ia–IIb | 16 (18.0%) | 4 (7.0%) | 3.531 | 0.083 |

| III | 73 (82.0%) | 53 (93.0%) | ||

| Response to 2–3 cycles of induction chemotherapy | ||||

| CR/PR | 67 (75.3%) | 47 (82.5%) | 1.045 | 0.412 |

| PD/SD | 22 (24.7%) | 10 (17.5%) | ||

| Irradiation techniques | ||||

| 3D-CRT | 44 (49.4%) | 38 (66.7%) | 4.189 | 0.041 |

| IMRT | 45 (50.6%) | 19 (33.3%) | ||

| Irradiation dose | ||||

| Total dose (Gy) | 50–60 | 50–66 | — | — |

| Fraction | 25–30 | 25–33 | ||

| Concurrent chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 38 (42.7%) | 7 (12.3%) | 15.076 | 0.000 |

| No | 51 (57.3%) | 50 (87.7%) | ||

| Prophylactic brain irradiation | ||||

| Yes | 38 (42.7%) | 14 (24.6%) | 4.983 | 0.033 |

| No | 51 (57.3%) | 43 (75.4%) | ||

| GTV (cm3) | ||||

| Median | 33.01 | 30.885 | — | — |

| Range | 0–287.9 | 0–422.3 |

3D-CRT, three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy; CR, complete remission; GTV, gross target volume; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; PD, partial disease; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; TRT, thoracic radiotherapy.

Treatment characteristics

Chemotherapy: All patients received two to six cycles (median 3 cycles) of IC, which predominantly consisted of an EP regimen (54.1%); other regimens included etoposide and carboplatin (EC) (36.3%) or other platinum-based doublet schemes (9.6%). Ninety-six patients received one to four cycles (median 2 cycles) of maintenance chemotherapy after TRT with regimens that included EP (68.8%), EC (17.7%), and other platinum-based schemes (13.5%). Only 45 patients received concurrent EP chemotherapy during radiotherapy. Chemotherapy was administered at three to four week intervals.

Radiotherapy: All patients received TRT; 82 patients were treated with three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT), and 64 patients were treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). The TRT regimens involved 1.8-2.1 Gy daily fractions, with a total dose of 50–66 Gy. The gross target volume (GTV) encompassed the primary tumor and any hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes and had minor axes at least 1 cm long with respect to the post-chemotherapy chest CT images. The primary tumor volume was contoured using a lung window, whereas abnormal lymph node volumes were delineated using a mediastinal window. The clinical target volume (CTV) delineation was performed by expanding the GTV by 0.5 cm and including any mediastinal nodal regions initially involved. The planning target volume (PTV) was created by expanding the CTV with adequate margins in all directions (usually 0.5–1 cm). At least 95% of the PTV was covered by the prescribed dose. Dose constraints for the lung were ≤20 Gy for the mean lung dose (MLD) and ≤35% for V20 (V20 ≤30% if patients received concurrent chemoradiotherapy). The dose constraint for the heart was V30 ≤40%, and for the esophagus was V50 ≤50% (VXX = % of the whole organ at risk receiving ≥ xx Gy). The dose to the spinal cord could not exceed 45 Gy. Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) was only offered to patients who achieved complete or near complete responses to chemoradiotherapy.

Data analysis

Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Locoregional recurrence (LRR) was defined as recurrence at the primary tumor site or in the mediastinal or supraclavicular nodal regions; recurrence beyond these areas was considered distant metastasis (DM). Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured from the time of diagnosis until LRR or DM occurrence or was censored at the date of the last follow-up examination. LRR and DM were diagnosed either by imaging (CT or positron emission tomography/computed tomography) or biopsy. OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the difference in survival rates between the groups was compared with the χ2 test. The Cox proportional hazards model was performed to determine the hazard ratio (HR) for OS.

Results

The median follow-up time of the survival patients was 43.9 months (range, 28.1–64.5 months). Forty-four patients (30.1%) were still alive at the last follow-up. The median OS of the entire group was 25.4 months (range, 5.6–64.5 months). The one, two and three-year OS was 86.3%, 52.1%, and 37.7%, respectively. The median PFS was 15.4 months (range, 4.0–64.5 months), and the one, two and three-year PFS was 61.6%, 37.0%, and 35.6%, respectively. Ninety-seven patients experienced disease progression, 53 patients had LRR, 78 patients had DM, and 34 patients had both. The most common site of DM was the brain (44.9%), followed by bone (28.2%), liver (26.9%), and other organs (25.6%).

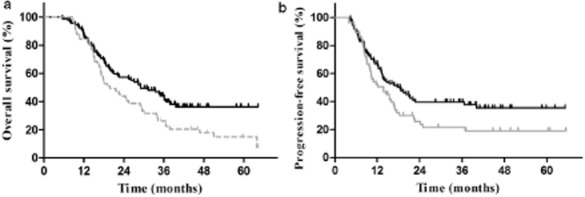

The early TRT group had significantly improved OS compared with the late TRT group; the median OS was 29.0 and 19.9 months, respectively (P = 0.018) (Fig 1). Patients who achieved CR or PR after two to three cycles of IC showed better survival than those who did not. The median OS was 28.4 and 17.8 months (P = 0.021). Other factors associated with longer OS, according to univariate analyses, were age ≤60 years, PCI, and smaller GTV (P < 0.05) (Table 1). In multivariate analysis, GTV (P = 0.026; HR = 1.004; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.000–1.007), and PCI (P = 0.026; HR = 0.595; 95% CI, 0.376–0.941) remained independent risk factors for OS. GTV was considered a continuous variable, and our results showed that the HR for death increased 0.4% per cm3 increase in GTV.

Figure 1.

(a) Overall survival in all patients (P = 0.018). (b) Progression-free survival in all patients (P = 0.049).  , early TRT;

, early TRT;  , late TRT.

, late TRT.

Among the abovementioned factors, only the timing of TRT was significantly correlated with PFS. PFS in the early and late TRT groups was 18.5 and 13.8 months, respectively (P = 0.049) (Fig 1). The one, two and three-year DM in the late TRT group was significantly higher than those in the early TRT group (40.6%, 64.3%, and 69.2% vs. 26.3%, 46.6%, and 48.0%, respectively, P = 0.035). However, the difference in the LRR rate in the two groups was not statistically significant (28.5%, 57.6%, and 57.6%, vs. 17.3%, 38.3%, and 38.3% P = 0.066).

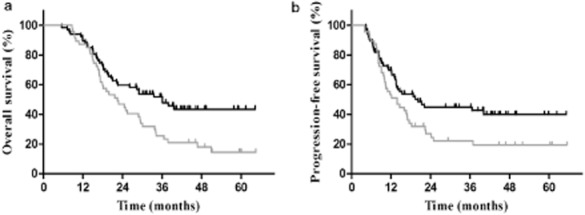

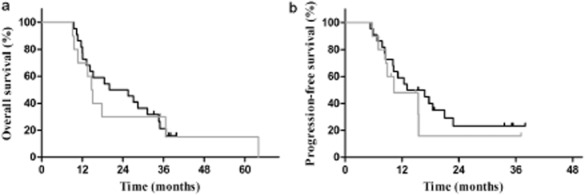

In subgroup analysis, in the 114 patients who achieved CR or PR after IC, the patients who received early TRT had improved survival compared with those who received delayed TRT. The median OS was 36.1 for the early TRT subgroup compared with 22.5 months for the late TRT subgroup, and the three-year OS was 52.2% and 25.5%, respectively (P = 0.009). The median PFS was 20.2 and 13.8 months and the three-year PFS was 44.9% versus 22.1% (P = 0.038) (Fig 2). Among patients with SD or PD responses to IC, there was no statistical difference in survival outcome between the early and late TRT subgroups; the median OS was 20.0 and 14.7 months and the three-year OS was 21.2% and 30.0%, respectively (P = 0.770). The median PFS was 13.1 and 10.3 months, respectively, and the three-year PFS was 17.5% versus 16.0% (P = 0.483) (Table 3) (Fig 3).

Figure 2.

(a) Overall survival in patients who achieved complete remission (CR) or partial remission (PR) after two to three cycles of induction chemotherapy (P = 0.009). (b) Progression-free survival in patients who achieved CR or PR after two to three cycles of induction chemotherapy (P = 0.038).  , early TRT;

, early TRT;  , late TRT.

, late TRT.

Table 3.

Survival in patients with different induction chemotherapy responses in early and late TRT groups

| Response to IC | CR/PR | χ2 | P | SD/PD | χ2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early TRT | Late TRT | Early TRT | Late TRT | |||||

| Timing of TRT | (n = 67) | (n = 47) | (n = 22) | (n = 10) | ||||

| Median OS (m) | 36.1 | 22.5 | 6.824 | 0.009 | 20.0 | 14.7 | 0.419 | 0.770 |

| 3-year OS (%) | 52.2 | 25.5 | 21.2 | 30.0 | ||||

| Median PFS (m) | 20.2 | 13.8 | 4.303 | 0.038 | 13.1 | 10.3 | 0.493 | 0.483 |

| 3-year PFS (%) | 44.9 | 22.1 | 17.5 | 16.0 | ||||

IC, induction chemotherapy; CR, complete remission; OS, overall survival; PD, partial disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; TRT, thoracic radiotherapy.

Figure 3.

(a) Overall survival in patients who achieved partial disease (PD) or stable disease (SD) after two to three cycles of induction chemotherapy (P = 0.770). (b) Progression-free survival in patients who achieved PD or SD after two to three cycles of induction chemotherapy (P = 0.483).  , early TRT;

, early TRT;  , late TRT.

, late TRT.

Toxicity

The observed toxicities are summarized in Table 4. No grade 4 or higher severe adverse events were observed. Grade 2 pneumonitis was identified in 8.9% of the patients, and grade 3 pneumonitis occurred in 2.1%. Only 6.2% of the patients experienced grade 2 esophagitis, and none of the patients experienced grade ≥3 esophagitis. The grade 2 and 3 neutropenia rates were 6.2% and 2.1%, respectively. No significant difference in toxicities was found between the early and late TRT groups.

Table 4.

Radiotherapy-related toxicities and side effects

| Group | Total | Early TRT group | Late TRT group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiation pneumonitis | |||

| Grade 2 | 13 (8.9%) | 7 (7.9%) | 6 (10.5%) |

| Grade 3 | 3 (2.1%) | 2 (2.2%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Radiation esophagitis | |||

| Grade 2 | 9 (6.2%) | 5 (5.6%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hematological | |||

| Grade 2 | 9 (6.2%) | 6 (6.9%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Grade 3 | 3 (2.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.8%) |

TRT, thoracic radiotherapy.

Discussion

The median OS of 25.4 months in our study is encouraging, compared with the literature.2 We used a once-daily TRT regimen, rather than the accelerated hyperfractionated TRT approach, because of its time-saving convenience and the fact that it resulted in a decreased rate of severe adverse events.12 As expected, our study demonstrated relatively low toxic effects.

The famous INT0096 study validated the use of concurrent chemotherapy with TRT as first-line treatment for LS-SCLC; however, the optimal timing of TRT is still controversial. Randomized trials and meta-analyses focusing on this topic have reported inconsistent results; specifically, some demonstrated a survival benefit from early TRT,3–8 whereas others did not.9,13 However, the majority of the evidence suggests a modest survival benefit associated with an earlier initiation of TRT. In our study, improved OS and PFS were observed in patients who received early TRT. This result may be partially because of the fact that a higher proportion of patients in the early TRT group received concurrent chemoradiotherapy, compared with the late TRT group. Patients who received early TRT typically presented with good hematopoietic function and could tolerate concurrent chemoradiotherapy, and it is widely known that concurrent chemoradiotherapy is superior to a sequential regimen in the treatment of SCLC.3,7 More importantly, patients in the early TRT group had short durations between the start of chemotherapy and radiotherapy administration, which has been demonstrated to affect survival in several previous studies.5,6,14,15 Murray et al. reported that the prolongation of SER (time between the start of any treatment and the end of radiation therapy) resulted in more frequent brain metastasis,6 and a study from Japan yielded similar results, causing the author to speculate that SER affects survival because of the probability of distant metastasis, but not local control.15 This tendency was also demonstrated in our study; specifically, the DM rates in the late TRT group were significantly higher than those in the early TRT group, and the LRR rates were not significantly different between the two groups. This phenomenon could be explained by the theory of somatic mutation of drug resistance occurring in the SCLC cells. Among the LS-SCLC patients, some had chemotherapy-resistant tumors that were confined to the primary site; the early initiation of TRT could potentially eradicate these resistant clones before they spread outward, thereby decreasing the DM rate.6

The timing of TRT has been the subject of several studies. However, most studies defined early TRT as starting radiotherapy within one to eight weeks of the first day of chemotherapy,3,4,6,8 and they focused on the impact of different chemotherapy regimens and radiation fractionation schemes on the timing of TRT.5 To our knowledge, few studies have investigated the impact of the response to IC on decision-making with regard to the timing of TRT. In one study, researchers found that radiation treatment planning can be optimized to reduce the radiation dose to normal tissue as a result of tumor shrinkage after the first cycle of chemotherapy, and an additional cycle of chemotherapy did not increase this benefit. They, therefore, concluded that initiating thoracic radiation therapy during the second cycle of chemotherapy may be a reasonable strategy.16 This study did not include a survival analysis, and patients who were not sensitive to chemotherapy were not taken into consideration. In our study, we analyzed survival based on the response to two to three cycles of IC, and subsequently used subgroup analyses to evaluate the impact of response to the first two to three cycles chemotherapy on decision-making in the timing of TRT.

Our results revealed that patients who achieved CR or PR after IC had a longer OS than those who did not, in accordance with earlier reports.17,18 Fujii et al. determined that patients who did not achieve CR or PR after the first cycle of chemoradiotherapy had poorer outcomes, even though objective responses were ultimately achieved through subsequent treatment.18 Sirohi et al. reported that NSCLC patients with SD after two courses of initial first-line chemotherapy had poorer outcomes than those with a PR.17 Thus, the early response to chemotherapy can aid in the prediction of long-term survival.

In addition, considering that SCLC is highly responsive to chemotherapy and that the GTV is delineated with reference to the post-chemotherapy chest CT images, we assumed that the GTV could reflect the response to chemotherapy to a certain extent; thus, a smaller volume could be a surrogate for a good response to chemotherapy, and could also facilitate quantitative analysis because it can be calculated by treatment planning systems. In our study, patients with smaller GTV had significantly longer survival times and the HR for death increased by 0.4% per cm3 increase in GTV; similar to the results from a previous study demonstrating that for patients with SCLC, GTV was an independent risk factor for survival.19 However, the definitions of GTV differed between the studies; the GTV in the previous study consisted of the post-chemotherapy tumor volume and pre-chemotherapy nodal volume, which was similar to our CTV measurement.

In subgroup analysis, we took the response to two to three cycles of IC into account as a stratification factor and analyzed the impact of TRT timing on survival. We found that among the patients who achieved CR or PR after IC, the early TRT subgroup had significantly longer OS and PFS times. Patients with PD or SD after IC also tended to achieve longer survival times when they received early TRT rather than late TRT, although these results were not statistically significant. The small number of patients who obtained poor responses to IC may explain this result; the inclusion of more patients may solve this problem. It is also possible that the absence of early responses to chemotherapy may predict poor survival and that the timing of TRT is not as important for these patients. The availability of additional mature data is required to obtain a definitive conclusion, but the existing evidence indicates that early TRT is still recommended, especially for patients who have good responses to two to three cycles of IC.

As a retrospective study, our study has some limitations. The major limitation is the fact that only 45 (30%) patients received concurrent chemoradiotherapy in this study, which can be explained by three reasons. Firstly, the criteria for patients included into this study were those who received induction chemotherapy, meaning that most patients were not candidates for early concurrent CRT when age, physical condition, and tumor burden were taken into account, especially when they presented with poor performance status or severe comorbidities, or when they had bulky tumors. Secondly, as nearly 40% of patients in this research received more than three cycles of IC, the accumulated side effects lowered their tolerance of concurrent chemoradiotherapy; therefore, only 12.3% of these patients received concurrent CRT. Finally, a patient’s expectation is another reason. The small proportion of patients who received concurrent chemoradiotherapy in this study may limit its applicability to some degree. Other limitations include the retrospective nature of this study and the heterogeneity of the baseline characteristics and treatment regimens in each treatment group. Well-designed, prospective, randomized clinical trials are warranted.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that early TRT is recommended, especially in patients who obtain a good response to two to three cycles of IC. Well-designed, prospective studies are warranted to investigate whether patients with PD or SD after two to three cycles of IC could benefit from early TRT initiation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Tianjin Antic Cancer Specialized Plan Major Reserch Project, China (NO. 12ZCDZSY15900).

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

References

- Turrisi ATIII, Kim K, Blum R, et al. Twice-daily compared with once-daily thoracic radiotherapy in limited small-cell lung cancer treated concurrently with cisplatin and etoposide. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:265–271. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901283400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lally BE, Urbanic JJ, Blackstock AW, Miller AA, Perry MC. Small cell lung cancer: Have we made any progress over the last 25 years? Oncologist. 2007;12:1096–1104. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-9-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ruysscher D, Pijls-Johannesma M, Vansteenkiste J, Kester A, Rutten I, Lambin P. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised, controlled trials of the timing of chest radiotherapy in patients with limited-stage, small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:543–552. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijls-Johannesma M, De Ruysscher D, Vansteenkiste J, Kester A, Rutten I, Lambin P. Timing of chest radiotherapy in patients with limited stage small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:461–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried DB, Morris DE, Poole C, et al. Systematic review evaluating the timing of thoracic radiation therapy in combined modality therapy for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4837–4845. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray N, Coy P, Pater JL, et al. Importance of timing for thoracic irradiation in the combined modality treatment of limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. The National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:336–344. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada M, Fukuoka M, Kawahara M, et al. Phase III study of concurrent versus sequential thoracic radiotherapy in combination with cisplatin and etoposide for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: Results of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study 9104. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3054–3060. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Acimovic L, Milisavljevic S. Initial versus delayed accelerated hyperfractionated radiation therapy and concurrent chemotherapy in limited small-cell lung cancer: a randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:893–900. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro SG, James LE, Rudd RM, et al. Early compared with late radiotherapy in combined modality treatment for limited disease small-cell lung cancer: A London Lung Cancer Group multicenter randomized clinical trial and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3823–3830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun JM, Ahn YC, Choi EK, et al. Phase III trial of concurrent thoracic radiotherapy with either first- or third-cycle chemotherapy for limited-disease small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2088–2092. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WK, Shepherd FA, Feld R, Osoba D, Dang P, Deboer G. VP-16 and cisplatin as first-line therapy for small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3:1471–1477. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.11.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socinski MA, Bogart JA. Limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: The current status of combined-modality therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4137–4145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarlos DV, Samantas E, Briassoulis E, et al. Randomized comparison of early versus late hyperfractionated thoracic irradiation concurrently with chemotherapy in limited disease small-cell lung cancer: A randomized phase II study of the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (HeCOG) Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1231–1238. doi: 10.1023/a:1012295131640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ruysscher D, Pijls-Johannesma M, Bentzen SM, et al. Time between the first day of chemotherapy and the last day of chest radiation is the most important predictor of survival in limited-disease small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1057–1063. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu T, Oizumi Y, Kunieda E, Tamai Y, Akiba T, Kogawa A. Definitive chemoradiotherapy of limited-disease small cell lung cancer: Retrospective analysis of new predictive factors affecting treatment results. Oncol Lett. 2011;2:855–860. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia B, Wang JZ, Liu Q, Cheng JY, Zhu ZF, Fu XL. Quantitative analysis of tumor shrinkage due to chemotherapy and its implication for radiation treatment planning in limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:216. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirohi B, Ashley S, Norton A, et al. Early response to platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer may predict survival. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:735–740. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31811f3a7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii M, Hotta K, Takigawa N, et al. Influence of the timing of tumor regression after the initiation of chemoradiotherapy on prognosis in patients with limited-disease small-cell lung cancer achieving objective response. Lung Cancer. 2012;78:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymen B, Van Loon J, van Baardwijk A, et al. Total gross tumor volume is an independent prognostic factor in patients treated with selective nodal irradiation for stage I to III small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:1319–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]