Abstract

We present the first reported case of lung large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) with spontaneous regression followed by progression. An 85-year-old woman presented with a 2.8-cm nodule in the right upper lung lobe on chest computed tomography. After four months, the tumor decreased to 1.8 cm and remained unchanged in size for the next three months, but it grew to 8.6 cm and invaded the mediastinal fat tissue after approximately one year. Ultrasound echo-guided percutaneous biopsy revealed the tumor to be LCNEC. The patient underwent a right upper lobectomy with lymph node dissection. She had a good postoperative course with no complications. Physicians and surgeons should be aware that radiographic regression of a pulmonary nodule does not necessarily exclude the possibility of lung cancer.

Keywords: Lung large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, progression, spontaneous regression

Introduction

Spontaneous regression of a malignancy is defined as the partial or complete disappearance of malignant disease without any medical treatment.1 This phenomenon is extremely rare, with an estimated incidence of less than one in 60 000–100 000 cases.1

Spontaneous regression has most often been noted in malignant melanoma (0.22–0.27%), renal cell cancer (0.3–4.0%), low-grade non-Hodgkins’s lymphoma (3.7–15%), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (3.7–15%), and neuroblastoma in children (10%).2,3 The phenomenon is extremely rare in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and only two of the 176 tumors with spontaneous regression reported by Cole were lung cancer (1 squamous cell carcinoma and 1 undifferentiated).1 We observed a rare and interesting case of lung large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) that regressed spontaneously, then progressed rapidly.

Case report

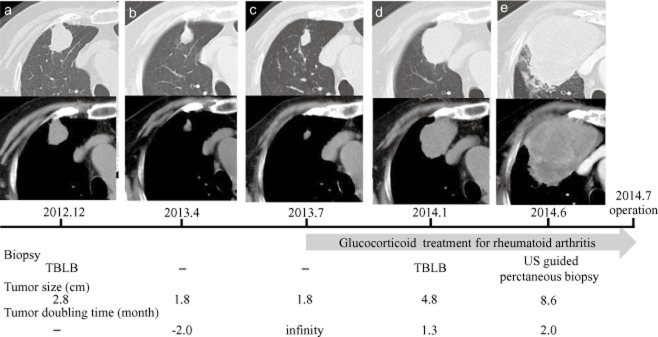

An 85-year-old woman with a history of smoking presented with an abnormal shadow on chest X-ray, which was performed as part of a pre-operative evaluation for osteoarthritis of the knee in December 2012. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 2.8 cm nodule in the right upper lung lobe (Fig 1a) and fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) showed uptake only within the nodule. Although transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) was negative, cytology of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from the right upper bronchi showed atypical cells suspicious for malignancy.

Figure 1.

Chest computed tomography scans showing the tumor shadow in the right upper lung lobe (in chronological order). The tumor shadow size and doubling times are presented. The patient underwent three biopsies. In July 2013, she was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis and began to receive glucocorticoid treatment. TBLB: transbronchial lung biopsy, US: ultrasound.

The patient was referred to our hospital for curative pulmonary resection in March 2013. Her physical examination was unremarkable, and her blood examination, including tumor markers, showed anemia with a hemoglobin value of 10.2 mg/dL. The cause of the anemia was not clear despite scrutiny. In April 2013, the size of the tumor shadow decreased from 2.8 to 1.8 cm (Fig 1b). We strongly suspected the tumor was benign rather than malignant and planned to perform a follow-up imaging examination. The tumor shadow remained unchanged for the next three months (Fig 1c). In July 2013, the patient was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis and began to receive glucocorticoid treatment. In January 2014, the tumor increased from 1.8 to 4.8 cm (Fig 1d) and a TBLB of the tumor was performed with suspicions of inflammatory disease or malignancy; however results of the TBLB were inconclusive. A chest CT scan was repeated in June 2014 and showed that the tumor shadow had further enlarged to 8.6 cm, with swelling of the mediastinal lymph nodes and suspected invasion of the superior vena cava and chest wall (Fig 1e). FDG-PET showed uptake within the tumor with a maximal standard uptake value of 23.6, but did not show uptake within the mediastinal lymph nodes. An ultrasound-guided biopsy of the tumor revealed a proliferation of tumor cells with large and irregular nuclei (Fig 2a). We diagnosed primary lung cancer, cT4N0M0, stage IIIA, according to the TNM (tumor node metastasis) Classification of Malignant Tumors (7th edition).

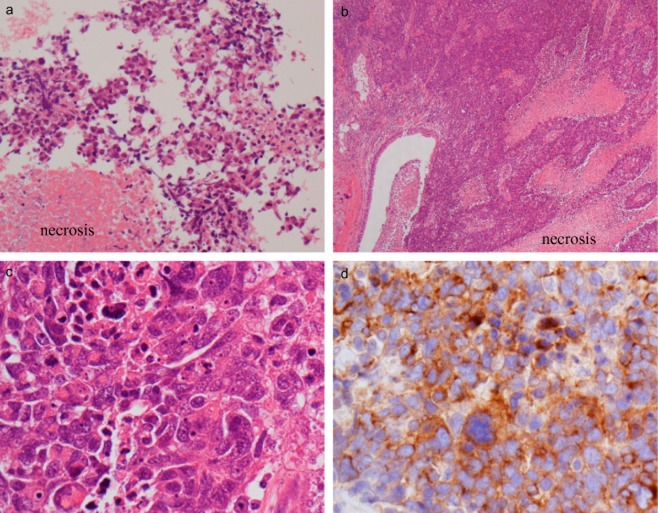

Figure 2.

(a) Biopsy tissue. The tumor showed a proliferation of tumor cells with large and irregular nuclei and necrosis (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] stain, × 200). (b–d) Surgical resected tissue. The histopathological findings from were similar to that from the biopsy tissue (b: H&E stain, × 40 and c: H&E stain, ×400, respectively). (d) We diagnosed a large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma based on immunohistochemical study; the tumor was positive for synaptophysin.

A right upper lobectomy with lymph node dissection in the hilum and right upper mediastinum was performed. Although the tumor had invaded the mediastinal fat tissue and parietal pleura, it did not invade the superior vena cava. The patient experienced a good postoperative course with no complications. On pathologic examination, the tumor was 7.5 cm in diameter and invaded the mediastinal fat tissue, but the lymph nodes did not show any evidence of metastasis. The histopathological results were similar to those from the biopsied tissue, and we diagnosed lung LCNEC, pathological stage IIIA (T4N0M0), based on immunohistochemical studies. The tumor was positive for synaptophysin, thyroid transcription factor-1, and cytokeratin 7, and was negative for chromogranin, CD56, and p63 (Fig 2b–d). The patient did not receive postoperative cytotoxic chemotherapy because of her own request and her advanced age.

Discussion

Our patient presents the first reported case of lung LCNEC with spontaneous regression. Furthermore, there have been no reports of spontaneous regression followed by rapid progression in primary lung cancer. To the best of our knowledge, 25 NSCLC tumors with spontaneous regression have been previously reported, including reviews by Kappauf et al.3 and Haruki et al4 (Table 1).3–8,10 Among these cases, 15 tumors were squamous cell carcinomas, eight were adenocarcinomas, three were large cell carcinomas, and one was NSCLC.

Table 1.

Previously reported cases of spontaneous regression in non-small cell lung cancer

| Case | Author | Year | Age/Gender | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blades et al.† | 1954 | 59/M | SQ |

| 2 | Boyd et al.† | 1966 | 56/M | AD |

| 3 | Margolis et al.† | 1967 | 58/M | AD |

| 4 | Emerson et al.†‡ | 1968 | 63/M | SQ |

| 5 | Bell et al.† | 1970 | 37/M | SQ |

| 6 | Smith et al.† | 1971 | 59/M | SQ |

| 7 | Smith et al.† | 1971 | 43/M | SQ |

| 8 | Depierre et al.† | 1984 | 57/M | SQ |

| 9 | Kato et al.‡ | 1986 | 55/F | SQ |

| 10 | Sperduto et al.‡ | 1988 | 61/M | SQ |

| 11 | Papac et al.† | 1990 | 62/F | AD |

| 12 | Kappauf et al.3 | 1997 | 61/M | AD |

| 13 | Leo et al.‡ | 1999 | 59/M | LCC |

| 14 | Saito et al.‡ | 1999 | 59/M | AD |

| 15 | Cafferata et al.‡ | 2004 | 68/M | AD |

| 16 | Kato et al.‡ | 2005 | 60/M | AD |

| 17 | Pujol et al.5 | 2007 | 75/F | SQ |

| 18 | Moriyama et al.‡ | 2008 | 45/M | LCC |

| 19 | Gladwish et al.6 | 2010 | 81/F | SQ |

| 20 | Haruki et al.4 | 2010 | 69/F | AD |

| 21 | Mizuno et al.7 | 2011 | 62/M | LCC |

| 22 | Furukawa et al.8 | 2011 | 56/M | SQ |

| 23 | Choi et al.9 | 2013 | 71/M | SQ |

| 24 | Hwang et al.10 | 2013 | 62/M | NSCLC |

| 25 | Present case | 2014 | 86/F | LCNEC |

In our case, the tumor spontaneously regressed and subsequently showed rapid progression after the initiation of glucocorticoid treatment. Although several possible mechanisms of spontaneous regression have been presented, the details remain unclear.1,3 Among the proposed mechanisms, immunological activation may be one of the more reasonable. Infiltration with CD8-positive lymphocytes4 and a high degree of natural killing activity11 have been reported within malignant tissues. If immunological activation was involved with the spontaneous regression of the tumor in our case, it may be reasonable to surmise that immunosuppression from glucocorticoid treatment could have affected the rapid progression of the tumor. However, it was difficult to fully evaluate the reasons for spontaneous regression in this case because blood and tissue samples were not available from the time of spontaneous regression.

Conclusion

This is the first report of spontaneous regression followed by progression in lung LCNEC. Physicians and surgeons should be aware that the radiographic regression of a pulmonary nodule does not necessarily exclude the possibility of lung cancer.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Takao Sato, M.D. (Department of Pathology, Kinki University Faculty of Medicine) for his helpful suggestions regarding the pathological findings.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

References

- Cole WH. Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:201–209. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930170302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis GB, Stam HJ. The spontaneous regression of cancer. A review of cases from 1900 to 1987. Acta Oncol. 1990;29:545–550. doi: 10.3109/02841869009090048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappauf H, Gallmeier WM, Wünsch PH, et al. Complete spontaneous remission in a patient with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Case report, review of the literature, and discussion of possible biological pathways involved. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:1031–1039. doi: 10.1023/a:1008209618128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruki T, Nakamura H, Taniguchi Y, et al. Spontaneous regression of lung adenocarcinoma: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2010;40:1155–1158. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol JL, Godard AL, Jacot W, Labauge P. Spontaneous complete remission of a non-small cell lung cancer associated with anti-Hu antibody syndrome. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:168–170. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e31802f1c9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladwish A, Clarke K, Bezjak A. Spontaneous regression in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2010;2010:bcr0720103147. doi: 10.1136/bcr.07.2010.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T, Usami N, Okasaka T, Kawaguchi K, Okagawa T, Yokoi K. Complete spontaneous regression of non-small cell lung cancer followed by adrenal relapse. Chest. 2011;140:527–528. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa M, Oto T, Yamane M, Toyooka S, Kiura K, Miyoshi S. Spontaneous regression of primary lung cancer arising from an emphysematous bulla. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17:577–579. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.10.01638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SM, Go H, Chung DH, Yim JJ. Spontaneous regression of squamous cell lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:e5–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1417IM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang ED, Kim YJ, Leem AY, et al. Spontaneous regression of non-small cell lung cancer in a patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a case report. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2013;75:214–217. doi: 10.4046/trd.2013.75.5.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K, Kikuchi M, Funai N, Matsuzaki M, Shimamoto Y. Natural killing activity in patients with spontaneous regression of malignant lymphoma. J Clin Immunol. 1996;16:334–339. doi: 10.1007/BF01541669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]