Abstract

Background

First- and second-generation smallpox vaccines are contraindicated in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). A new smallpox vaccine is needed to protect this population in the context of biodefense preparedness. The focus of this study was to compare the safety and immunogenicity of a replication-deficient, highly attenuated smallpox vaccine modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) in HIV-infected and healthy subjects.

Methods

An open-label, controlled Phase II trial was conducted at 36 centers in the United States and Puerto Rico for HIV-infected and healthy subjects. Subjects received 2 doses of MVA administered 4 weeks apart. Safety was evaluated by assessment of adverse events, focused physical exams, electrocardiogram recordings, and safety laboratories. Immune responses were assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and a plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT).

Results

Five hundred seventy-nine subjects were vaccinated at least once and had data available for analysis. Rates of ELISA seropositivity were comparably high in vaccinia-naive healthy and HIV-infected subjects, whereas PRNT seropositivity rates were higher in healthy compared with HIV-infected subjects. Modified vaccinia Ankara was safe and well tolerated with no adverse impact on viral load or CD4 counts. There were no cases of myo-/pericarditis reported.

Conclusions

Modified vaccinia Ankara was safe and immunogenic in subjects infected with HIV and represents a promising smallpox vaccine candidate for use in immunocompromised populations.

Keywords: HIV infection, immunocompromised, MVA, smallpox, vaccination

In 1980, the World Health Organization (WHO) certified the eradication of smallpox disease following a global vaccination effort [1]. This vaccination program and the subsequent destruction and consolidation of known variola virus (VARV) samples into WHO reference laboratories significantly reduced the likelihood of accidental reintroduction of the causative agent of smallpox. Nonetheless, the intentional reintroduction of smallpox from undeclared samples, accidental release, or intentional regeneration of the viral genome made possible by advances in molecular biology remains a possibility [2, 3]. These concerns, combined with the potential devastating impact of disease in an immunologically naive population in which routine vaccination ended over 40 years ago, have led to efforts to mitigate the potential reintroduction of VARV.

Vaccination remains the most effective means of preventing transmission of VARV and reducing the impact of smallpox disease. First- and second-generation smallpox vaccines, based upon vaccinia virus (VACV), an orthopoxvirus closely related to VARV, are highly protective and were extensively used during the global eradication program. However, these live replication-competent VACV vaccines have the potential to cause serious complications including progressive vaccinia, eczema vaccinatum, generalized vaccinia, encephalitis, and myo-/pericarditis, especially in individuals with immunodeficiency states or skin disorders such as atopic dermatitis (AD) [4, 5]. These findings led the US Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices to recommend against vaccination with first- and second-generation smallpox vaccines for individuals (and their household contacts) who have a history or presence of eczema or AD, or who are immunocompromised such as those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Based on these recommendations, it has been estimated that up to 25% of the population are ineligible to receive the first- and second-generation smallpox vaccines [6].

Modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) was used during the 1970s in more than 120 000 people, including children with immune deficiencies, for priming prior to administration with a first- and second-generation smallpox vaccine [7]. Modified vaccinia Ankara was derived by more than 570 passages of the VACV strain chorioallantois vaccinia Ankara in primary chicken embryo fibroblast cells and essentially became replication restricted to avian and certain mammalian cells [8], resulting in a product incapable of replicating in human cells or severely immunocompromised animals [9]. Recent trials with MVA as a stand-alone smallpox vaccine have demonstrated a favorable safety profile [10–13]. Modified vaccinia Ankara was also shown to induce immune responses comparable with conventional VACV-based vaccines [14, 15]. Populations at an increased risk to receive first- and second-generation smallpox vaccines (ie, subjects with HIV-infection [16], atopic dermatitis [17], or immune-suppressive therapy [18], respectively) tolerated vaccination with MVA well and had a good immune response. To further evaluate MVA as a smallpox vaccine in at-risk individuals, this Phase II trial was conducted to compare the safety and immunogenicity of MVA in HIV-infected individuals and healthy controls.

METHODS

Study Vaccine

Modified vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic (MVA-BN) was manufactured by IDT Biologika GmbH (Dessau-Roßlau, Germany) according to Good Manufacturing Practices guidelines and was provided by Bavarian Nordic A/S (Kvistgaard, Denmark) as a liquid-frozen product (0.5 mL) with a nominal titer of 1 × 108 TCID50.

Study Design

A multicenter, open-label, controlled Phase II trial was conducted between June 12, 2006 and March 25, 2009. Vaccinia-experienced or vaccinia-naive, HIV-infected and healthy male and female subjects (18–55 years of age) were enrolled at 36 centers in the United States and Puerto Rico. Main inclusion criteria for healthy subjects were a negative antibody test for HIV and hepatitis C. Human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects were eligible if they had confirmed HIV infection, had a CD4+ count of 200–750 cells/µL, and were either on antiretroviral therapy for at least 6 months or not receiving antiretroviral therapy for at least 8 weeks prior to enrollment. Main exclusion criteria for all subjects included the following: pregnancy; acute disease (any illness with or without a fever at the time of enrollment); uncontrolled infections; known or suspected impairment of the immune system other than HIV infection, including chronic administration of immunosuppressive drugs starting from 6 months prior to study participation; administration of immunoglobulins (Igs) and/or blood products 3 months prior to inclusion; any clinically significant hematological, renal, hepatic, pulmonary, central nervous system, or gastrointestinal disorders; uncontrolled psychiatric disorders; history, clinical manifestation, or increased risk of cardiovascular disease; allergy to vaccine components; positive hepatitis B surface antigen; and any vaccination prior to inclusion (14 days for killed/inactivated, 3 months for live vaccines).

Based on HIV infection status and smallpox vaccination history (determined by subject report and examination for a typical vaccinia scar) at screening, subjects were allocated to 1 of 4 study groups to receive 2 subcutaneous doses of 1 × 108 TCID50 MVA-BN 4 weeks apart. After enrollment (Day 0; first vaccination), subjects returned at weeks 1, 4 (second vaccination), 6 and 8 for immunogenicity and/or safety assessments. A follow-up via phone was scheduled 6 months after the second vaccination; for a subgroup of subjects, the 6-month follow-up was performed as an onsite visit.

Written informed consent was obtained from each subject before enrollment. The study was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Boards, and all procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki, ICH-Good Clinical Practice and US Code of Federal Regulation applicable for clinical trials. An independent Data Safety Monitoring Board oversaw the safety of volunteers participating in the study.

Safety Assessment

The occurrence, relationship, intensity, and duration of any unsolicited adverse events (AEs) reported by the subject or detected by the investigator at any time during the study were recorded at each of the 4 postvaccination study visits. Serious AEs (SAEs) were monitored throughout the study up to the 6-month follow-up visit. Solicited AE, ie, predefined local reactions (erythema, swelling, and pain) and general symptoms (pyrexia, headache, myalgia, chills, nausea, and fatigue), were assessed for occurrence, intensity, and duration by the subjects using diary cards for the 8 postvaccination days starting on the day of each vaccination. Severe (ie, Grade 3) injection-site reactions of erythema and swelling were defined as a diameter of ≥100 mm and for pain if preventing normal activity; general symptoms were Grade 3 if daily activity was prevented. Grade 3 pyrexia was defined as body temperature ≥39.0°C and <40.0°C; ≥40.0°C was Grade 4 (life-threatening or disabling). The occurrence of any cardiac symptoms, elevated cardiac enzymes, and clinically significant electrocardiogram (ECG) changes were defined as AEs of special interest (AESI). Physical exams, including vital signs, were performed at every study visit. In addition, all subjects underwent ECG and safety laboratories for hematology and serum chemistry (including cardiac enzymes) at week 1 and 6, and additionally if indicated. Human immunodeficiency virus RNA levels and CD4/CD8 T-cell counts were monitored in HIV-infected subjects at baseline and at each postvaccination visit.

Immunogenicity Assessment

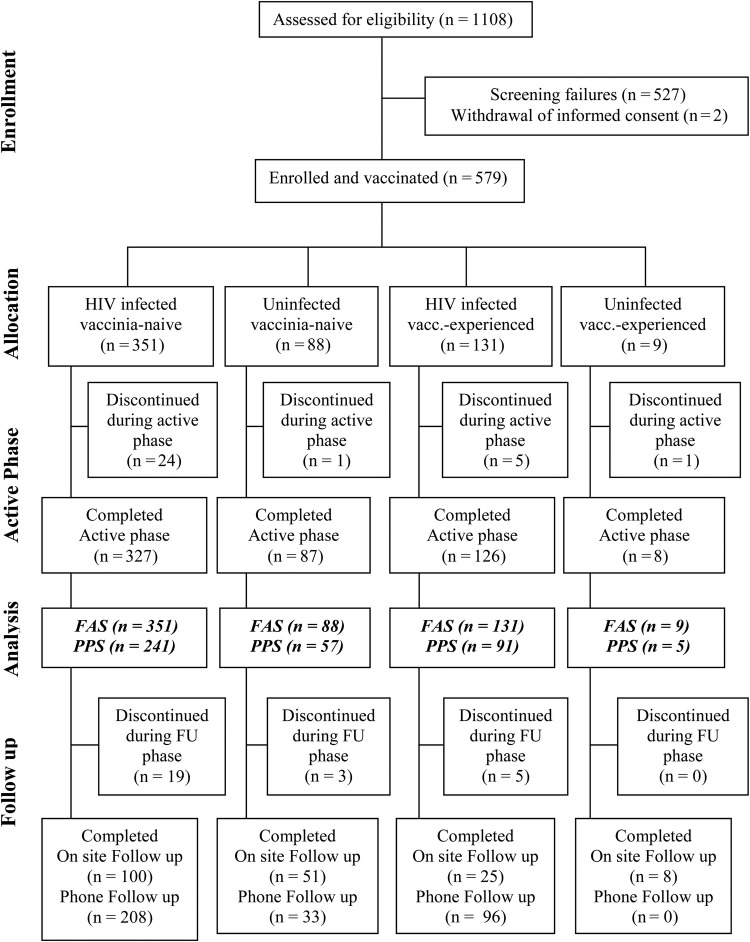

Blood was drawn at baseline before the first vaccination, 1 week and 4 weeks after the first, as well as 2 weeks and 4 weeks after the second vaccination. For subgroup of subjects, who were attending the onsite follow-up visit, a follow-up sample was drawn at least 26 weeks after first vaccination (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Disposition of subjects and data sets analyzed. Of 1108 screened volunteers, 581 subjects were assessed eligible for enrolment, 579 subjects were allocated to 1 of 4 study groups, and all 579 subjects received at least 1 vaccination (full analysis set [FAS]). One hundred eighty-five subjects were excluded from the per-protocol analysis set ([PPS] n = 394). The active phase of the study is up to the visit for the last vaccination and the follow-up (FU) phase is at least 26 weeks after last vaccination. Only 164 from 501 subjects came to an on-site visit for the Follow-up, for 337 of 501 subjects the safety-relevant information was gathered by telephone. For all other subjects, the safety-relevant information was gathered by telephone FU. In case any serious safety issues were detected via telephone, the subject was asked to appear for an onsite visit. Abbreviation: vacc., vaccinia.

Antibody responses to VACV were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and a plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) on heat-inactivated serum samples. For subjects seronegative before vaccination, seroconversion was defined as the appearance of a titer equal to or higher than the detection limit (50 for ELISA and 6 for PRNT). For subjects seropositive before vaccination, seroconversion was defined as at least a 2-fold increase in titer compared with the prevaccination titer. Titers below the detection limit were replaced by 1 for geometric mean titer (GMT) calculations.

Vaccinia Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Total IgG antibodies were measured using an automated ELISA on a Biomek FX ELISA robot (Beckman Coulter, Germany). The 96-well plates were coated overnight with a crude antigen preparation (MVA-infected chicken embryo fibroblast lysate) in 200 mM Na2CO3, pH 9.6. After washing, plates were blocked with a solution of phosphate-buffered saline, 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 0.05% Tween 20. Plates were washed again before the addition of test sera, which were titrated in duplicate 2-fold serial dilutions starting at 1:50. After a 1-hour incubation period, plates were washed, incubated for 1 hour with detection antibody (goat anti-human horseradish peroxidase, Sigma-Aldrich), and washed again before a 30-minute development with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate. The optical density was measured at 450 nm. The antibody titers were calculated by linear regression and defined as the serum dilution that resulted in the optical density of the assay cutoff (0.3).

Vaccinia Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test

Neutralizing antibodies were determined using a PRNT50. Test sera were serially diluted in duplicate in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/7% FBS and added to an equal volume of vaccinia virus (Western Reserve strain, ABI) and then incubated overnight at 37°C. After neutralization, the sera were transferred to confluent Vero cell monolayers in 48-well cell culture plates. After 70 minutes adsorption, overlay-medium (DMEM, 7% FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, and 0.5% methyl cellulose) was added and then incubated overnight. After crystal violet staining, plates were scanned and automatically counted. The number of plaques was fitted as a linear function of the log10 of the dilution, and the titer was expressed as the serum dilution where the virus was neutralized by 50% compared with the 100% virus control (average number of plaques per 40 wells).

Statistical Analysis

The final sample size of at least 300 HIV-infected, vaccinia-naive subjects was determined by regulatory requirements to identify a potential safety signal of at least 1% with 80% power. Safety and immunogenicity assessments were stratified according to the prevaccination status of subjects to evaluate the potential impact of pre-existing immunity. The HIV-infected study population was further stratified according to their CD4 counts at baseline (200–349, 350–500, 501–750 cells/µL).

The safety analysis was conducted on the Full Analysis Set (FAS) including all subjects who received at least 1 vaccination. The immunogenicity analysis was primarily performed on the per-protocol analysis set (PPS), comprising all subjects without major protocol violations, but was also repeated on the FAS for comparison. All analyses were performed in an exploratory manner at the 5% significance level without any adjustments for multiple testing. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS.

Demographic parameters between groups were compared at baseline using descriptive statistics i.e. proportions for gender or race and mean and standard deviations for quantitative measurements (e.g. age or body mass index). Safety laboratory parameters were compared over time by calculating the change from baseline and calculating the mean and 95% confidence interval of the mean.

Adverse events were summarized using frequency tables, and differences between rates in groups were tested using Fisher's exact test. For the immunogenicity data (ELISA and PRNT titers), the seroconversion rates (ELISA and PRNT) were compared using an exact 95% confidence interval for the difference between the percentages of healthy and HIV-infected subjects. Differences in GMTs between 2 groups were tested using a homoscedastic t test, or a one-way analysis of variance test in the case of more than 2 groups, using the log10 titers.

RESULTS

Study Population

Five hundred seventy-nine volunteers were enrolled in the study: 439 vaccinia-naive (88 healthy, 351 HIV-infected) and 140 vaccinia-experienced (9 healthy, 131 HIV-infected) subjects received at least 1 vaccination, had data available for analysis, and were included in the FAS (Figure 1). An amendment of the protocol to fulfill regulatory requirements meant enrollment into study groups was unbalanced. Five hundred forty-one subjects received both vaccinations. Of these, 185 subjects (34%) had a protocol violation (predefined according to regulatory authority requirements) and were excluded from the PPS accordingly. Because only 5 healthy vaccinia-experienced subjects were included in the PPS, this group was not powered for comparisons with other groups.

Human immunodeficiency virus-infected and healthy study populations were demographically balanced except that there were more males than females in the HIV-infected study groups and the HIV-infected vaccinia-naive group was older than the healthy cohort. The main difference between vaccinia-naive and vaccinia-experienced groups was the lower age of vaccinia-naive compared with vaccinia-experienced subjects (Table 1). Based on CD4 counts at screening (200–349, 350–500, 501–750 cells/µL), HIV-infected subjects were further divided into 3 subgroups with similar proportions of vaccinia-naive and vaccinia-experienced in each group (89 [25.4%], 163 [46.4%], and 99 [28.2%]; and 24 [18.3%], 61 [46.6%], and 46 [35.1%], respectively).

Table 1.

Demographic Data and HIV Status (FAS, N = 579)a

| HIV-Infected Vaccinia-Naive (N = 351) | Uninfected Vaccinia-Naive (N = 88) | HIV-Infected Vaccinia-Experienced (N = 131) | Uninfected Vaccinia-Experienced (N = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 36.8 ± 8.0 | 28.9 ± 7.1 | 44.6 ± 5.1 | 45.6 ± 8.9 |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 26.7 ± 5.6 | 27.6 ± 7.4 | 27.1 ± 5.0 | 26.0 ± 4.7 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 287 (81.8) | 38 (43.2) | 110 (84.0) | 5 (55.6) |

| Female | 64 (18.2) | 50 (56.8) | 21 (16.0) | 4 (44.4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Caucasian | 161 (45.9) | 49 (55.7) | 60 (45.8) | 5 (55.6) |

| African-American | 117 (33.3) | 15 (17.0) | 43 (32.8) | 3 (33.3) |

| Hispanic | 65 (18.5) | 14 (15.9) | 27 (20.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Oriental/Asian | 1 (0.3) | 5 (5.7) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (11.1) |

| Other | 7 (2.0) | 5 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| CD4+ T Cells, median (range), number/mm3 | ||||

| Baseline | 420 (200–897) | N/A | 449 (199–741) | N/A |

| End of trial | 403 (138–1056) | N/A | 435 (273–762) | N/A |

| HIV Status, n (%) | ||||

| HAART therapy | 277 (79) | N/A | 120 (92) | N/A |

| Baseline viral load <400 copies | 278 (79) | N/A | 118 (90) | N/A |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FAS, full analysis set; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; N, number of subjects; n, number of subjects in the specified category; N/A, not applicable; SD, standard deviation; %, percentage based on N.

a The main difference in demographics between groups was the younger age of vaccinia-naive compared with vaccinia-experienced subjects, which is to be expected because mass vaccination programs ended in the 1970s, and the higher percentage of male subjects in the HIV-infected compared with healthy populations, representative of and reflecting the gender balance of the general HIV-infected population in the United States.

Two healthy subjects and 29 HIV-infected subjects discontinued the study prematurely. Reasons for discontinuation included subject unable or unwilling to comply with study procedures (8), adverse event (6), subject request (6), improper timing of a licensed vaccine (5), CD4 dropped below prespecified level (4), administration of prohibited medications (1), and unspecified reason (1).

Safety

A summary of all categories of AE reported during the treatment period of the study is provided in Table 2. A majority of subjects (>90%) experienced at least 1 AE, with a slightly lower incidence in vaccinia-experienced compared with vaccinia-naive subjects. In general, occurrence of unsolicited and solicited AE and adverse drug reactions (ADRs), including grade ≥3 events, was similar in all 4 groups.

Table 2.

Summary of Adverse Events (AE) During the Treatment Period (FAS, N = 579)

| HIV-Infected Vaccinia-Naive (N* = 351) | Uninfected Vaccinia-Naive (N* = 88) | HIV-Infected Vaccinia-Experienced (N* = 131) | Uninfected Vaccinia-Experienced (N* = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject based, n (%) | ||||

| At least 1 AE documented | 318 (90.6) | 87 (98.9) | 113 (86.3) | 7 (77.8) |

| At least 1 | ||||

| Nonserious AE | 318 (90.6) | 87 (98.9) | 113 (86.3) | 7 (77.8) |

| Causally related AEa | 205 (58.4) | 59 (67.0) | 61 (46.6) | 3 (33.3) |

| AE graded ≥3b | 65 (18.5) | 18 (20.5) | 17 (13.0) | 1 (11.1) |

| Causally related AE graded ≥3b | 26 (7.4) | 7 (8.0) | 5 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unsolicited AE (29-day FU) | 236 (67.2) | 59 (67.0) | 73 (55.7) | 3 (33.3) |

| Solicited local AE (8-day FU) | 272 (77.5) | 82 (93.2) | 95 (72.5) | 7 (77.8) |

| Solicited general AE (8-day FU) | 198 (56.4) | 55 (62.5) | 64 (48.9) | 3 (33.3) |

| Special interest AE | 41 (11.7) | 13 (14.8) | 9 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Causally related special interest AE | 8 (2.3) | 7 (7.9) | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| AE leading to withdrawal from study | 1 (0.3) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| AE leading to withdrawal from 2nd vaccination | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) |

- solicited local AEs: pain Grade 3 = spontaneously painful/prevented normal activity, erythema/swelling Grade 3 = greatest surface diameter ≥100 mm.

- solicited general AEs: Grade 3 = AE, which prevented daily activities or body temperature ≥39 to <40°C, Grade 4 = AE life-threatening or disabling or body temperature ≥40°C.

- unsolicited AEs: Grade 3 = AE prevents daily activities, Grade 4 = AE life-threatening or disabling.

There may be findings in more than 1 category. The table shows AEs during the treatment period excluding the follow-up phase of the study. There were no causally related AE grade 4 reported during the study.

Abbreviations: FAS, full analysis set; FU, follow-up; N, number of subjects; N*, number of subjects in the specified group; n, number of subjects with at least 1 report of 1 particular kind of symptom; %, percentage based on N*.

a Unsolicited or solicited general AE considered by the investigator to have a possible, probable, definite or missing relationship to study medication. Solicited local AEs are per definition considered related to study medication and were not included in the causality assessment depicted in this table.

b Intensity grades:

Of the 38 SAE reported during the study, all occurred in HIV-infected subjects and, except for 1, were assessed as not related to MVA. There was one possibly related SAE (pneumonia and pleurisy) with onset 1 day after the second vaccination, making the relationship unlikely because vaccination occurred during the incubation period of the infection. There was 1 nonrelated death due to suicide with benzodiazepine overdose in a subject with known bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

Six of the 31 subjects who discontinued the study prematurely withdrew due to an AE (all HIV-infected). Three cases with possible or probable relationship were due to injection-site dermatitis, (transient) decrease in neutrophils, or partial incomplete left branch bundle block (LBBB) that resolved spontaneously. The latter subject had normal ECGs before and after the incomplete LBBB, and all troponin levels were normal throughout the study for that individual.

Adverse events of special interest assessed as possibly related to the vaccination were reported in 7.9% of the healthy vaccinia-naïve population and 2.3% of the HIV-infected vaccinia-naïve population. Whereas in the HIV-infected vaccinia-experienced population only 1.5% of Adverse events of special interest assessed were reported as possibly related to the vaccination. The cases were mostly due to transient, minimally elevated troponin I elevations that were not associated with any ECG changes. All AESI were mild (grade 1) and transient, and none was indicative of myo- or pericarditis. The majority of unsolicited ADR reported with a frequency >2% were related to vaccination-site reactions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Most Common Unsolicited Adverse Reactions (Frequency >2%) During the 28-Day Follow-up Period After Both Vaccinations (FAS, N = 579)a

| System Organ Class Preferred Term | HIV-Infected Vaccinia-Naive (N* = 351) | Uninfected Vaccinia-Naive (N* = 88) | HIV-Infected Vaccinia-Experienced (N* = 131) | Uninfected Vaccinia-Experienced (N* = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration site conditions, n (%) | ||||

| Injection site pruritus, any grade | 72 (20.5) | 28 (31.8) | 25 (19.1) | 3 (33.3) |

| Injection site pruritus, Grade ≥3 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Injection site nodule, any grade | 4 (1.1) | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) |

| Injection site nodule, Grade ≥3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Injection site bruising, any grade | 2 (0.6) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Injection site bruising, Grade ≥3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Injection site warmth, any grade | 2 (0.6) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) |

| Injection site warmth, Grade ≥3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders, n (%) | ||||

| Vomiting, any grade | 1 (0.3) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Vomiting, Grade ≥3 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Investigations, n (%) | ||||

| Troponin I increased, any grade | 5 (1.4) | 5 (5.7) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) |

| Troponin I increased, Grade ≥3 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Abbreviations: FAS, full analysis set; N, number of subjects; N*, number of subjects in the specified group; n, number of subjects with at least 1 report of the specific local or systemic AE after either vaccination; %, percentages based on N*.

a A subject may have AEs reported in more than 1 category.

No clinically significant changes in CD4 counts or HIV viral load were observed during the treatment period, and there were no clinically significant changes in hematology and biochemistry. Injection-site pain, erythema, swelling, headache, myalgia, fatigues, nausea, and chills were the most prevalent local and systemic ADR, resolving within 3–5 days with none being graded as severe.

Immunogenicity Results

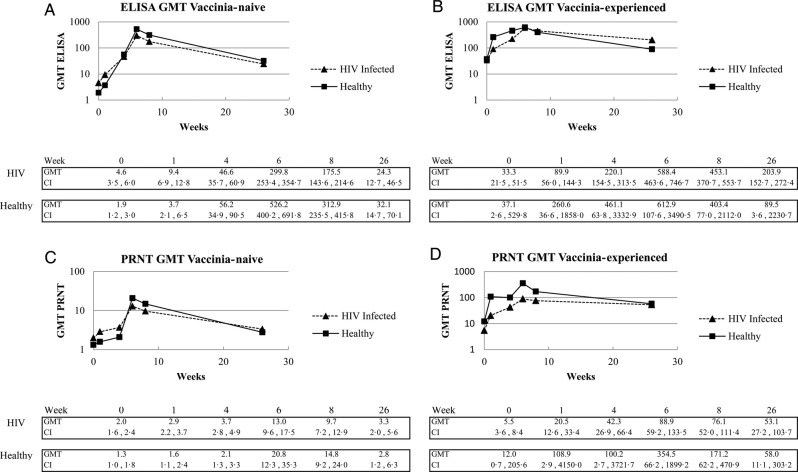

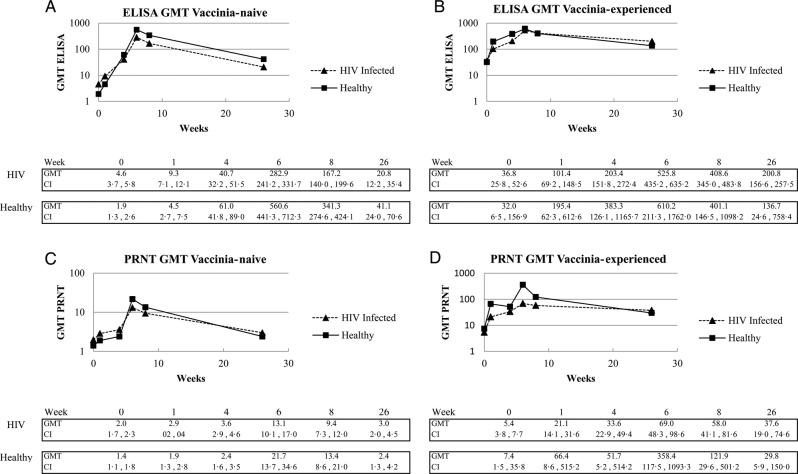

Immunogenicity data for the PPS are shown (n = 394; Figure 2); however, similar results were obtained for the FAS (n = 579), illustrating the robustness of the data (Figure 3). Higher baseline seropositivity rates were observed in HIV-infected vaccinia-naive subjects (35% for ELISA and 17% for PRNT) compared with healthy vaccinia-naive subjects (14% and 7%, respectively), although actual GMTs were low.

Figure 2.

Kinetics of humoral immune responses after 2 vaccinations with Modified vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic. Total and neutralizing antibody responses were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay ([ELISA] A and B) and plaque reduction neutralization test ([PRNT] C and D) using the Per Protocol Set. Abbreviation: GMT, geometric mean titer.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of humoral immune responses after 2 vaccinations with Modified vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic. Total and neutralizing antibody responses were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay ([ELISA] A and B) and plaque reduction neutralization test ([PRNT] C and D) using the Full Analysis Set. Abbreviation: GMT, geometric mean titer.

A rapid primary response was achieved in vaccinia-naive subjects: 86% of the healthy and 80% of the HIV-infected subjects were seropositive by ELISA 4 weeks after the first dose (week 4), increasing to 100.0% and 97.5% 2 weeks after the second dose. Similarly, 100% of healthy and 93% of HIV-infected vaccinia-experienced subjects were seropositive by ELISA after a single dose, the latter rising to 99% 2 weeks after the second dose. Baseline CD4 count had no impact on ELISA seropositivity rates in HIV-infected populations.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay GMTs (Figure 2A) were statistically higher in healthy compared with HIV-infected subjects at week 6 (P = .0030) and week 8 (P = .0094). Geometric mean titer in HIV-infected subjects tended to be lower with decreasing CD4 count, although not statistically significant (data not shown). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay GMTs in the vaccinia-experienced populations were not significantly different with a GMT of 461.1 and 220.1 in healthy and HIV-infected subjects after vaccination 1, rising to 612.9 and 588.4, respectively, after the second dose (Figure 2B).

Four weeks after the first dose, 19% of healthy and 30% of HIV-infected vaccinia-naive subjects were seropositive by the PRNT. Significantly higher seropositivity rates were measured for healthy subjects (81%) compared with HIV-infected subjects (61%) after dose 2 (P = .0055). Responses were similar across the different CD4 strata among HIV-infected subjects. Eighty percent of both healthy and HIV-infected vaccinia-experienced subjects were seropositive by PRNT after 1 dose, increasing further to 100% and 90%, respectively, after the second vaccination.

Neutralizing GMTs in vaccinia-naive subjects were low after dose 1 and increased to 21.7 in healthy and 13.1 in HIV-infected subjects, respectively after dose 2 (P = .17) (Figure 2C). Among HIV-infected subjects, there was no significant difference at any time point and no trends related to CD4 counts were observed. A rapid increase in GMT from baseline was seen in both vaccinia-experienced populations after dose 1, increasing after the second dose in both HIV-infected (88.9) and healthy subjects (354.5) (Figure 2D). In all 4 groups, there was a significant correlation between ELISA and PRNT titers at all study visits (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The primary goals of this study were to assess the safety and immunogenicity of MVA in immunocompromised subjects for whom replication competent smallpox vaccines are contraindicated. The results of this study demonstrate that the MVA smallpox vaccine was as safe and well tolerated in HIV-infected subjects with CD4 counts as low as 200 cells/µL as in healthy individuals, regardless of their previous smallpox vaccination status. Furthermore, MVA was able to induce a VACV-specific immune response in HIV-infected subjects.

Although a majority of the study subjects experienced at least 1 AE, frequencies were similar in HIV-infected and healthy subjects. The only SAE assessed as possibly related (pneumonia) was likely pre-existing given the onset of symptoms 1 day after vaccination. The majority of reported adverse reactions tended to be mild to moderate, quickly resolving, local and systemic ADR typically observed with vaccine administration. None of the reported AESI was indicative of myo- or pericarditis. Moreover, the 11 subjects with minimally elevated troponin levels reported during the study were evaluated by a cardiologist and deemed not to indicate myo- or pericardits. Given the very low elevation without any ECG or echocardiographic changes, the elevated troponin levels likely reflected a change in the central laboratory threshold for normal range during the active phase of the study, leading to false-positive results. There was no significant difference in the frequency of ADR or AESI in HIV-infected or healthy subjects. No safety signals were detected during the study including the 6-month follow-up and despite close cardiac monitoring, and no cardiac risk was identified.

These data are important because first- and second-generation live smallpox vaccines have been associated with myo-/pericarditis [19]. The fact that no cases of myo-/pericarditis were identified in this study, which was powered specifically to detect cardiac events at the frequency reported with live vaccines, suggests that the vaccine likely has a better cardiac safety profile than previous generation vaccines, confirming previously published data on cardiac monitoring after administration of MVA [20]. Nevertheless, it remains possible that larger clinical studies might detect rare clinical toxicity.

Immunogenicity of vaccines is of significant importance for immunocompromised subjects who are at risk for more severe disease. After 2 doses of MVA, high seropositivity rates were demonstrated in both HIV-infected and healthy subjects. Although total antibody titers were significantly higher in healthy compared with HIV-infected vaccinia-naive subjects, PRNT GMT values were similar at the 26 week follow-up visit. This result is consistent with the results of a smaller study [16], although the trial reported here included subjects with more advanced disease (CD4 count as low as 200 cells/µL compared with >350 cells/µL). Although a suppressed immune response in HIV-infected subjects is generally expected and frequently observed with other vaccines [21], total antibody titers in HIV-infected subjects were still high and comparable to titers in healthy subjects given first- and second-generation live smallpox vaccines [14, 16], justifying the conclusion that immune responses correlating to protection had been induced in this immunocompromised population.

As has been reported in other clinical studies evaluating MVA [10–13, 15–18] or first- and second-generation live smallpox vaccines [14], the total antibody response is higher, both in terms of the number of responders and in the magnitude of the response, compared with neutralizing antibody titers. Although neutralizing antibodies are considered an important immunological correlate of protection [22], other antibody functions such as complement fixation, antibody directed cellular cytotoxicity, and opsonization have been shown to play an important role in protection as well [23–27]. Antibodies responsible for these latter functions are likely captured better by an ELISA [28, 29]. In all reported trials for MVA, the PRNT and ELISA results were significantly correlated, as is the case in the present study, supporting the comprehensive assessment of humoral immune responses using the measurement of both PRNT and ELISA.

In both groups of vaccinia-experienced subjects, MVA was shown to significantly boost pre-existing immunity, supporting earlier findings that first- and second-generation smallpox vaccines induce a long-lived B cell memory [30]. This anamnestic response in vaccinia-experienced populations has previously been used as an indicator of clinical efficacy for first- and second-generation smallpox vaccines [24], and thus a single MVA vaccination seems to be sufficient to boost the protective immune response induced by first- and second-generation smallpox vaccines in the majority of immunosuppressed and healthy individuals.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the standard MVA dose and regimen established for healthy populations has a favorable safety and immunogenic profile in HIV-infected vaccinia-naive and vaccinia-experienced populations with CD4 counts of 200–750 cells/µL. The data from this study supported US Food and Drug Administration approval for emergency use of MVA in the event of a smallpox outbreak.

Acknowledgments

The following Investigators and Clinical Trials Sites recruited subjects for this trial: Thomas Jefferson, Health for Life Clinic, Little Rock, AR; Daniel Berger, Northstar Medical Center, Chicago, IL; Scott Parker University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL; Javier Morales-Ramirez, Clinical Research P.R., San Juan, Puerto Rico; Teresa Sligh, Providence Clinical Research, Burbank, CA; Patricia Salvato, Diversified Medical Practices, Houston, TX; Ian Frank, University of Pennsylvania, Division of Infectious Diseases, Philadelphia, PA; Barry Rodwick, Clinical Research of West Florida, Clearwater, FL; Jennifer Bartczak, Northpoint Medical, Ft. Lauderdale, FL; Patrick Nemechek, Nemechek Health Renewal, Kansas City, MO; Helmut Albrecht, University of South Carolina, Division of Infectious Diseases, Columbia, SC; Daniel Pearce, AltaMed Health Services Corporation, Los Angeles, CA; Barbara Wade, Infectious Diseases Associates of NW Florida, Pensacola, FL; Clifford Kinder, The Kinder Medical Group, Miami, FL; Melisssa Gaitanis, Brown Medical School, The Miriam Hospital, Providence, RI; Chiu-Bin Hsiao, Immunodeficiency Clinic, ECMC, Buffalo, NY; Phillip Brachman, Atlanta ID Group, Atlanta, GA; Nicholaos Bellos, Clinical Trials Dept. Dallas, TX; Mitchell Goldman, Indiana University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Disease Indianapolis, IN; David Haas, MD Vanderbilt University Vanderbilt AIDS Clinical Trials Center, Nashville, TN; Michelle Salvaggio, Clinical Trials Unit, Oklahoma City, OK; Isaac Marcadis, Palm Beach Research Center, West Palm Beach, FL; Carmen Zorrilla, University of Puerto Rico, Maternal Infant Studies Center (CEMI) Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico; Paul Cimoch, CSI Clinical Trials, Fountain Valley, CA; Daniel Warner, Consultive Medicine, Daytona Beach, FL; Miguel Madariaga, University of Nebraska, Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE; Fernando Garcia, Valley AIDS Council, Harlingen, TX; Melinda Campopiano, Clinical Trials Research Services, Pittsburg, PA; Steve O'Brien, Alta Bates Summit Medical Center, Clinical Trials Dept, Oakland, CA; Amneris Luque, University of Rochester School of Medicine, Rochester, NY; Sharon Frey, St. Louis University, Center for Vaccine Dev. St. Louis, MO; Data collection, management and analyses were performed by Kendle International (Cincinnati, OH). Design and conduct of the trial were managed by Bavarian Nordic A/S. The assistance of the following team members is appreciated: Cynthia Hughes, Courtney Anderson, Tammy Iames, Gwen Kelly (all Kendle), Nadine Uebler and Arielle Valette (all BN). We wish to gratefully acknowledge the trial participants that devoted their time and effort to this research endeavour.

Financial support. The study was funded by US Department of Health and Human Services (Contract no. HHSO100200700034C) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Contract no. N01-AI-40072).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors, except for those employed by Bavarian Nordic, received research grants from Bavarian Nordic to support the conduct of this trial. E. W., A. v. K., V. G., J. W., T. P. M., N. B., R. G., P. Y., S. R., J. M., N. A.-W., and P. C. were employees of Bavarian Nordic.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: 7th ASM Biodefense and Emerging Diseases Research Meeting, Baltimore, MD.

References

- 1. Breman JG, Arita I. The confirmation and maintenance of smallpox eradication. N Engl J Med 1980; 303:1263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mayr A. Smallpox vaccination and bioterrorism with pox viruses. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2003; 26:423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gaudioso J, Brooks TF, Furukawa, Lavanchy DO, Friedman D, Heegaard ED. Likelihood of Smallpox Recurrence. J Bioterr Biodef 2011; 2:106 10.4172/2157-2526.1000106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldstein JA, Neff JM, Lane JM, Koplan JP. Smallpox vaccination reactions, prophylaxis, and therapy of complications. Pediatrics 1975; 55:342–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lane JM, Ruben FL, Neff JM, Millar JD. Complications of smallpox vaccination, 1968: results of ten statewide surveys. J Infect Dis 1970; 122:303–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kemper AR, Davis MM, Freed GL. Expected adverse events in a mass smallpox vaccination campaign. Eff Clin Pract 2002; 5:84–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mayr A Stickl H Muller HK, et al. [The smallpox vaccination strain MVA: marker, genetic structure, experience gained with the parenteral vaccination and behavior in organisms with a debilitated defence mechanism (author's transl)]. Zentralbl Bakteriol [B] 1978; 167:375–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mayr A, Hochstein-Mintzel V, Stickl H. Passage history, properties, and use of attenuated vaccinia virus strain MVA. Infection 1975; 3:6–14. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Suter M Meisinger-Henschel C Tzatzaris M, et al. Modified vaccinia Ankara strains with identical coding sequences actually represent complex mixtures of viruses that determine the biological properties of each strain. Vaccine 2009; 27:7442–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vollmar J Arndtz N Eckl KM, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of IMVAMUNE, a promising candidate as a third generation smallpox vaccine. Vaccine 2006; 24:2065–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. von Krempelhuber A Vollmar J Pokorny R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, dose-finding Phase II study to evaluate immunogenicity and safety of the third generation smallpox vaccine candidate IMVAMUNE. Vaccine 2010; 28:1209–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frey SE Winokur PL Salata RA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of IMVAMUNE® smallpox vaccine using different strategies for a post event scenario. Vaccine 2013; 31:3025–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frey SE Winokur PL Hill H, et al. Phase II randomized, double-blinded comparison of a single high dose (5 × 108 TCID50) of modified vaccinia Ankara compared to a standard dose (1 × 108 TCID50) in healthy vaccinia-naïve individuals. Vaccine 2014; 32:2732–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frey SE Newman FK Kennedy JS, et al. Clinical and immunologic responses to multiple doses of IMVAMUNE (modified vaccinia Ankara) followed by Dryvax challenge. Vaccine 2007; 25:8562–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Damon IK Davidson WB Hughes CM, et al. Evaluation of smallpox vaccines using variola neutralization. J Gen Virol 2009; 90:1962–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Greenberg RN Overton ET Haas DW, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and surrogate markers of clinical efficacy for modified vaccinia Ankara as a smallpox vaccine in HIV-infected subjects. J Infect Dis 2013; 207:749–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sonnenburg F Perona P Darsow U, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia Ankara as a smallpox vaccine in people with atopic dermatitis. Vaccine 2014; 32:5696–5702. PMID:25149431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Walsh RW Wilck MB Dominguez DJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia Ankara in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Infect Dis 2013; 2007:1888–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Acambis. ACAM2000 Smallpox Vaccines: Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC). Acambis Briefing Document, April 2007 2007.

- 20. Elizaga ML Vasan S Marovich MA, et al. Prospective surveillance for cardiac adverse events in healthy adults receiving modified vaccinia ankara vaccines: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013; 8:e54407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Landrum M, Dolan M. Routine vaccination in HIV-infected adults. Infect Dis Clin Pract 2008; 16:85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Panchanathan V, Chaudhri G, Karupiah G. Correlates of protective immunity in poxvirus infection: where does antibody stand?Immunol Cell Biol 2008; 86:80–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benhnia MR McCausland MM Moyron J, et al. Vaccinia virus extracellular enveloped virion neutralization in vitro and protection in vivo depend on complement. J Virol 2009; 83:1201–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moulton EA, Atkinson JP, Buller RM. Surviving mousepox infection requires the complement system. PLoS Pathog 2008; 4:e1000249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parker AK Parker S Yokoyama WM, et al. Induction of natural killer cell responses by ectromelia virus controls infection. J Virol 2007; 81:4070–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karupiah G Coupar B Ramshaw I, et al. Vaccinia virus-mediated damage of murine ovaries and protection by virus-expressed interleukin-2. Immunol Cell Biol 1990; 68(Pt 5):325–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Benhnia MR Maybeno M Blum D, et al. Unusual features of vaccinia virus extracellular virion form neutralization resistance revealed in human antibody responses to the smallpox vaccine. J Virol 2013; 87:1569–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Manischewitz J King LR Bleckwenn NA, et al. Development of a novel vaccinia-neutralization assay based on reporter-gene expression. J Infect Dis 2003; 188:440–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Findlay JW Smith WC Lee JW, et al. Validation of immunoassays for bioanalysis: a pharmaceutical industry perspective. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2000; 21:1249–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Crotty S Felgner P Davies H, et al. Cutting edge: long-term B cell memory in humans after smallpox vaccination. J Immunol 2003; 171:4969–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]