Abstract

TRPV1 is expressed in a subpopulation of myelinated Aδ and unmyelinated C-fibers. TRPV1+ fibers are essential for the transmission of nociceptive thermal stimuli and for the establishment and maintenance of inflammatory hyperalgesia. We have previously shown that high-power, short-duration pulses from an infrared diode laser are capable of predominantly activating cutaneous TRPV1+ Aδ-fibers. Here we show that stimulating either subtype of TRPV1+ fiber in the paw during carrageenan-induced inflammation or following hind-paw incision elicits pronounced hyperalgesic responses, including prolonged paw guarding. The ultrapotent TRPV1 agonist resiniferatoxin (RTX) dose-dependently deactivates TRPV1+ fibers and blocks thermal nociceptive responses in baseline or inflamed conditions. Injecting sufficient doses of RTX peripherally renders animals unresponsive to laser stimulation even at the point of acute thermal skin damage. In contrast, Trpv1−/− mice, which are generally unresponsive to noxious thermal stimuli at lower power settings, exhibit withdrawal responses and inflammation-induced sensitization using high-power, short duration Aδ stimuli. In rats, systemic morphine suppresses paw withdrawal, inflammatory guarding, and hyperalgesia in a dose-dependent fashion using the same Aδ stimuli. The qualitative intensity of Aδ responses, the leftward shift of the stimulus-response curve, the increased guarding behaviors during carrageenan inflammation or after incision, and the reduction of Aδ responses with morphine suggest multiple roles for TRPV1+ Aδ fibers in nociceptive processes and their modulation of pathological pain conditions.

Keywords: Nociception, Analgesia, Chemoreceptors, Chronic Pain, Capsaicin

1. Introduction

Detection of impending or actual tissue damage is essential to the survival of an organism and depends upon primary afferent nociceptors responsive to a wide range of stimulus intensities and modalities [2,4]. For thermal stimuli in the noxious range, detection occurs through afferent fibers expressing TRPV1, a calcium and sodium permeable ion channel gated by heat, low pH, and a variety of endogenous ligands [20,54]. Experimental data from recordings of primary afferents and behavioral studies in mouse, rat, monkey, and human, as well as responses of cloned TRPV1 in heterologous expression systems, support the notion that channel opening, ion flux and action potential generation occur at heat intensities coincident with increased afferent firing and behavioral response [2,8–10,14,61]. However, the convergence of afferent fiber molecular properties and physiological classifications with clinical pain disorders and actions of therapeutic agents is an evolving subject of investigation. Classification based on recordings from monkey primary afferents has delineated 2 major sets of thermo-nociceptive fibers: the first is activated by adequate concentrations of the TRPV1 agonist capsaicin and nociceptive thermal stimuli and is termed type II Aδ mechanoheat (AMH) fibers. A second population of high thermal threshold nociceptors is relatively insensitive to capsaicin and is activated only at stimulus intensities supramaximal for behavioral responses, termed type I Aδ AMH fibers [69]. However, the identity of the thermoresponsive channels of these fibers has been an ongoing source of debate and investigation [36,38,57,73]. One possibility is that the high-threshold fibers respond not to thermal stimulation directly but rather to factors released by non-neural cells (eg, keratinocytes, fibroblasts) in the vicinity of heat-induced subclinical tissue damage [28,41,57,68,69]. Thus, in high temperatures, heat may play both direct and indirect roles in mediating nerve terminal depolarization.

Sensitization of Aδ- and C-fiber endings is an important factor in persistent and chronic pain conditions [36,41,49,64]. In the context of inflammatory processes, TRPV1-mediated hyperalgesia is associated with increased expression of the TRPV1 channel, alterations in its sensitivity by phosphorylation [5,53,56], and increased trafficking of the channel to the plasma membrane [75]. These cellular and molecular alterations underscore the complexities as well as the potentials for using TRPV1 antagonists [6,20,54,62], agonists [7,22,25,31], and positive allosteric modulators [32,39] in the therapeutic arena. However, among the AMH fibers, it has not yet been determined whether the capsaicin-sensitive TRPV1+ population is sensitized during inflammation, and the contribution of these fibers to hyperalgesia needs further investigation.

The present study explores behavioral responses to a range of stimulus intensities delivered with a 980 nm infrared diode laser and determines whether the laser-evoked responses are sensitized during inflammation. We also determine whether these responses can be triggered in the absence of the TRPV1 receptor or TRPV1+ afferents. Thus, we evaluated nociceptive and hyperalgesic responses in the context of genetic knockout of Trpv1 or deactivation of the entire TRPV1+ fiber with the potent TRPV1 agonist resiniferatoxin (RTX) administered intrathecally or intraplantar in animals at baseline, during peripheral inflammation, and after experimental surgical incision. We also investigate concentration-dependent and route-of-administration-dependent factors in the ability of RTX to inhibit both Aδ- and C-fiber-evoked behavioral responses and the ability of morphine to block Aδ-evoked nociceptive responses. We hypothesized that a range of Trpv1 expression in both Aδ- and C-fiber classes may be a molecular component that partially underlies the range of behavioral and physiological observations in the present and previous reports examining type I and II afferents and high-threshold fibers characterized as ‘‘silent nociceptors’’ that are activated by chemical inflammatory mediators [46,48]. The heterogeneity of Aδ-fibers, their further molecular characterization, and their potential as pharmacological targets are important considerations that emerge from the present studies.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350 g) and Trpv1−/− and wild-type C57/BL6 mice (−20 g, Jackson Laboratory, Farmington, CT, USA) were housed under a 12-hour light-dark cycle and allowed access to food and water ad libitum. The ambient temperature of the animals’ holding and testing rooms was 21 °C–22 °C. All efforts were made to minimize both animal numbers and distress during the experiments. All procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Committee for Research and Ethical Issues of the International Association for the Study of Pain and were approved by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Resiniferatoxin administration

Sealed glass ampoules of resiniferatoxin (RTX) (1 mg) were obtained from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). RTX was solubilized in 150 μL ice-cold 100% ethanol, diluted with 50 μL ddH2O, and supplemented with ascorbic acid to make a final RTX stock concentration of 5 μg/μL. It was further diluted to a working concentration of 100 ng/μL RTX in sterile vehicle (0.25% Tween 80, 2 mM ascorbic acid, 0.9% NaCl). Vehicle was used to dilute RTX (100 ng/μL) to lower working concentrations. All intraplantar injections were made using a total volume of 50 μL in rats and 20 μL in mice using a 300 μL zero dead volume tuberculin syringe with a fixed needle of 27 or 28 G for rats and 28 G for mice (Terumo Medical, Somerset, NJ, USA). In rats, intrathecal injections were delivered at 20 μL using a 22 G Stimuplex needle and performed under isoflurane anesthesia as described [31]. Carrageenan was administered 10 days after intrathecal injection, and behavioral testing occurred 24 hours later.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry and histology

Rats were deeply anesthetized with intraperitoneal pentobarbital and transcardially perfused with physiological saline followed by 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde. Dorsal root ganglia or a block of skin from the hind paw were removed and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections cut to a thickness of 5 μm were used for immunohistochemical (IHC) or histological examination. Sections were deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin-eosin or Masson trichrome to localize damage sites. IHC sections were subjected to antigen retrieval by 15-minute incubation at 100 °C with DAKO Envision (Carpinteria, CA, USA).

2.4. S100A8 immunocytochemistry

S100A8 immunostaining was performed on tissue obtained at 24 hours post stimulation using rabbit anti-S100A8 serum (a gift from P. Tessier) at a 1:1000 dilution, followed by donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated with an Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) fluorescent 2° antibody [49]. The S100A8 protein was used to show the presence of thermal damage based on the fact that this protein is highly expressed in neutrophils, which rapidly infiltrate the zone of tissue damage [51]. Staining with hematoxylin and eosin or Masson trichrome stain (not shown) of the skin strip shown in Fig. 4 did not reveal tissue damage except at the highest stimulus intensity.

Fig. 4.

Withdrawal responses and skin damage to high-intensity and supramaximal infrared diode laser stimuli. (A) Paw withdrawal frequency was determined in intraplantar high-dose (250 ng) RTX- and vehicle-treated rats to Aδ stimulation at supramaximal laser intensities (n = 6). Rats were stimulated only once per energy setting to minimize skin damage. (B) Rats showed significantly elevated withdrawal latencies following intraplantar RTX treatment. In 4 of the tests, responses were blocked up to 30 seconds of stimulation, an arbitrarily chosen late cut-off (n = 6 rats). Filled circles indicate the presence of skin damage or edema post stimulation. High-dose, local RTX blockage of response to damaging stimuli is consistent with the presence of a low amount of TRPV1 on these damage-responsive afferent fibers. (C) In mice, withdrawal frequencies were tested to Aδ thermal pulses at 4.46 W/mm2. Stimulation with noxious (100 ms; 0.45 J/mm2) and damaging (200 ms; 0.90 J/mm2) durations resulted in similar withdrawal frequencies between Trpv1−/− and wt mice, whereas wt mice treated with 10 ng intraplantar RTX exhibited significantly reduced withdrawal frequencies (n = 6). (D, E) Epidermal neutrophil infiltration in paw skin of RTX-treated rats 24 hours after C-fiber stimulation with (D) sub-damaging and (E) damaging stimuli. Arrows show neutrophils immunostained for S100A8, a highly expressed neutrophil marker. C = cornified layer; S = spinous layer; D = dermis. (F) S100A8 immunostaining following progressively increasing Aδ thermal stimulation in an anesthetized rat. Behavioral withdrawal occurs at laser powers well below those that cause tissue damage. Increasing the duration to 200 ms produced a subclinical effect because no damage was seen with hematoxylin-eosin staining (not shown), but did provoke neutrophil diapedesis just under the zone of thermal stimulation. Increasing the duration to 300 ms produced a small burn in the skin, much greater neutrophil infiltration, and visible damage with hematoxylin-eosin staining (not shown).

2.5. TRPV1-NF200 immunostaining

Double immunofluorescent labeling for TRPV1-neurofilament 200 was performed using polyclonal rabbit anti-rat TRPV1 antibodies, 1:1000 (Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO, USA) and mouse monoclonal antibody N52 (1:2000) to the C-terminal fragment of neurofilament 200 (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA). After deparaffinization, antigen retrieval and 2 washes in PBS, sections were incubated in blocking solution (10% normal horse serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 2 hours. The 2 primary antibodies were mixed in DAKO protein block solution and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Sections were rinsed 3 times in PBS followed by another 20-minute block and then addition of Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-mouse and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Invitrogen), for TRPV1 and NF200, respectively, in blocking solution and incubated for at least 2 hours. After three 5-minute washes with PBS, the slide-mounted sections were cover-slipped with Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). Images were acquired on an Olympus BX-60 microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera (Hammamatsu City, Japan) using separate band-pass filters, then merged. Counts were obtained from sections of paraffin embedded DRG with a 20− objective. We counted 22 fields from 3 sections in 3 rats, for a total of 1086 counted DRG cells (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Assessment of TRPV1 localization in myelinated primary afferents. Immunocytochemical staining was performed for (A) neurofilament 200 protein, a myelination marker in primary afferent neurons, and (B) TRPV1. The proportions of single- and double-labeled neuronal perikarya were counted in L4-L5 DRG sections from 3 rats (C). A total of 1086 cells were counted. Of the 479 TRPV1+ neurons, the majority were singly labeled (430), with 11.4% coexpressing NF200 to varying extents, as indicated (D). This proportion is within the parameters of other published studies, which report a range of colocalization between 5% and 30% (see text).

2.6. Thermal stimulus parameters

An infrared diode laser (LASS-10 M; Lasmed, Mountain View, CA, USA) with an output wavelength of 980 nm and maximum power of 20W was used to generate thermal stimuli. Calibration and testing procedures have been described [12,49,70]. For calibration, laser power/energy was measured using a meter with an infrared sensor (Nova II meter, L30A-10 MM sensor; Ophir Optronics, Jerusalem, Israel) placed perpendicular to the beam. The laser collimator was attached to a support and positioned below the glass testing platform, with the beam perpendicular to the surface. Great care was taken to keep the glass surface clean and dry. Loss through the glass platform used for testing, measured equidistant from the level of the plantar hind paw to the collimator, was observed to be 19% and was consistent at all laser energies evaluated. To determine the skin-heating rate, stepwise measurements were performed on anesthetized rats and mice using a forward-looking infrared thermal camera (ThermoVision SC6000 FLIR system; Process Sensors, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) with an acquisition rate of 400 frames per second. Skin heating was measured without interposed glass. Once the calibration curve/function was determined, values were adjusted by 19% to account for loss through the glass. This yielded the calibration curve in Fig. 1A. Beam diameter was determined by measuring the aiming beam spot at the 2 respective focal lengths.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of laser-evoked withdrawal responses. (A) Linear relationship between laser power per area and heating rate measured as change in skin surface temperature per second. (B) Stimulus-response curve showing the frequency of paw withdrawal following activation of Aδ fibers at increasing laser intensity (n = 16 rats). (C) Response severity based on behavioral ratings increases with increasing laser intensity. (D, E) Effect of unilateral hind-paw inflammation on Aδ responses. Probability of paw withdrawal was determined for the ipsilateral (D) carrageenan-injected doses of 2 and 6 mg in 150 μL and for the contralateral (E), saline-injected paws (n = 5 rats). (D) Note the leftward shift in the stimulus response curve in the inflamed paw after carrageenan, consistent with sensitization, P < 0.05. (E) Withdrawal frequency was decreased in the uninflamed contralateral paw, suggesting the animals inhibited the abrupt transfer of weight to the inflamed paw, P < 0.05. (F) The Aδ stimulus provoked a brisk and vigorous paw withdrawal even if the hind paw was inflamed and the graph of the first observable movement following Aδ stimulus was identical for the inflamed hind paw and the withdrawal latency from a noninflamed rat (ie, neither paw was inflamed). (G) Licking and guarding nocifensive behaviors are significantly increased following Aδ laser stimulation under inflamed conditions compared to noninflamed rats, P < 0.001. (H) C-fiber stimulation of the hind paw. The scatterplot of withdrawal latencies for uninflamed animals (n = 16 rats) shows the distribution about the mean (8.66 ± 0.25 s). (I) Effect of unilateral hind-paw inflammation on C-fiber responses (n = 5 rats). Both 2 mg and 6 mg carrageenan produced significant decreases in withdrawal latency consistent with hyperalgesia (P < 0.001), but no further sensitization occurred with the 6 mg dose of carrageenan.

2.7. Behavioral testing paradigms, general

The testing paradigm is similar to that which we have previously established, using a radiant-heat stimulus from a focused incandescent light source [24]. Rats (n = 3 to 4) and mice (n = 5 to 6) were placed unrestrained under plastic enclosures on an elevated glass platform. The enclosures were large enough for the animals to move freely. Rats were habituated for 15–20 minutes prior to testing, while mice required 30–45 minutes.

2.8. C-fiber testing

Cutaneous C-fibers were selectively activated by low-rate heating starting at a low energy with a 5 mm diameter beam [49,70]. This protocol delivers an increasing ramp of heat [12] that terminates with paw withdrawal. The beam was aimed at the midplantar footpad with the paw continuously stimulated until withdrawal occurred, and the latency was measured by the experimenter using a digital stopwatch. Preliminary studies determined that typical baseline withdrawal latencies for adult Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350 g) subjected to a 1.6W (0.0815 W/mm2) stimulus were between −8 and 9 seconds, similar to times obtained with a Hargreaves device radiant-heat stimulus [24]. In adult C57/BL6 mice (−20 g), 1.3W (0.066 W/mm2) was used, resulting in latencies of −4 to 5 seconds.

2.9. Aδ-fiber testing

Aδ-fibers were selectively activated with a high rate of heating using a high-energy, 100 ms pulse and a 1.6 mm diameter beam. A thermal damage cut-off for each stimulus paradigm was determined via immunohistological examination of stimulated, anesthetized rats (Fig. 4). The response to a high-energy Aδ stimulus in normal rats and mice is brisk and behaviorally productive, characterized by rapid paw withdrawal and shaking, orientation of the head to the stimulated paw, and licking. Our standard protocol for evaluation of Aδ-fiber responses involved stimulation of a toe, midplantar footpad, and then heel, resulting in 3 trials per paw. We initially chose this paradigm to minimize the possibility, especially with low-intensity stimuli, that a negative response was due solely to anatomical variation (eg, skin thickness or innervation density) or to some other physical factor. The interstimulus interval, per animal, was typically 2 to 3 minutes. Stimulus intensity was progressively increased during the session, starting with energies that, in normal animals, did not cause a behavioral response, and ending at the Aδ cut-off (−6 W/mm2). The session for an individual animal was often terminated (ie, the stimulus intensity was no longer increased) when ≥90% of trials gave maximum behavioral responses using our rating scale (a rating of 4; see below). If performed on the same day, responses to C-fiber stimuli were always determined after evaluation of Aδ responses.

2.10. Behavioral rating scale for response to Aδ stimuli

The severity of the Aδ behavioral responses were dependent upon stimulus intensity and on the genetic and pharmacological manipulations (eg, TRPV1 gene deletion, RTX or morphine treatment). We noted a distinct range of reproducible behaviors, and to capture this information, we developed a subjective rating scale for behavioral intensity. The categories were: 0 = no visible response; 1 = slight twitch of the body or abrupt movement of head; 2 = withdrawal of the foot off the glass, including either a rapid return of the paw to the glass or the animal walking away; 3 = withdrawal of the foot, characterized by prolonged paw shaking or guarding and orientation of the head without licking; 4 = strong withdrawal, which includes paw shaking, orientation and licking. A similar progressive pattern of nocifensive behaviors has been reported with the use of a CO2 laser on rats [42].

2.11. High-speed videography

A high-speed, 12-bit monochrome camera (AOS Technologies, Baden, Switzerland) was used to capture precisely the rapid movements associated with withdrawal activity, as previously described [49]. Images were acquired at 500 frames per second and were recorded for a total of 2 second, which was sufficient to capture the entire 100 ms laser pulse plus nocifensive behaviors, including the eventual withdrawal of the stimulated limb. In some recordings, to view the musculature better, the fur on the hindquarters of the animal was shaved to reveal the lower back, hips and legs. Great care was taken to record only after the rats were habituated to the testing enclosure and sitting still at the moment of stimulation, irrespective of posture. The middle or index toe was targeted with a 100 ms stimulus (5.12 or 6.08 W/mm2). For calculating the latency required to observe nocifensive behaviors, frames were counted from the onset of laser stimulation to the onset of the first-observable movement or muscle twitch. As previously shown, only the last 70 ms of the 100 ms, 6.08 W/mm2 stimulus is within the noxious range [49]. Thus, when determining the behavioral latency, 30 ms was subtracted from the total time.

2.12. Inflammatory and incisional pain models

Carrageenan was suspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline and injected in a volume of 150 μL in rats. Intraplantar injections were made subcutaneously using a 300 μL zero dead volume tuberculin syringe with a fixed needle of 27 or 28 G for rats and 28 G for mice (Terumo Medical). Most rat experiments were performed using 2 mg per injection, except in 1 experiment (Fig. 1) where 6 mg was also examined. Mice were given a subcutaneous intraplantar injection of 25 μL of a 4% carrageenan solution in PBS (1 mg carrageenan/injection). Testing was performed at 24 hours after carrageenan injection.

For behavioral evaluation of the surgical incision model [1], rats were placed on an elevated wire mesh platform for 4 minutes, then were visually examined 3 times, once each at 4, 5, and 6 minutes, and were scored on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3. A 0 signified full weight-bearing throughout 3 5-second trials with 1 minute intervals between observation periods. A 1 corresponded with weight placed on most of the paw but not the entire paw. These rats did not place weight on the incision or they placed weight on the entire paw but would lift it during the trial. A score of 2 was given when a rat placed weight only on its toes during each 5-second trial. A score of 3 signified that the foot was in the air during each of the 5-second observation periods.

2.13. Morphine analgesia

A drug stock of morphine sulfate (25 mg/mL) was diluted with physiological saline to make lower dosages. Rats received equivalent volumes per kg body weight. Control rats received saline only. Injections were made subcutaneously between the shoulder blades. Immediately after the injection, rats were placed on the testing platform to acclimate. Pilot studies revealed that the peak effect occurred 45 to 60 minutes after the injection, and all subsequent testing was performed within this 15-minute window. A dose-response to subcutaneously injected morphine was separately established for the C-fiber stimulus (0.0815 W/mm2) and 1 high-power (5.6 W/mm2) Aδ stimulus.

2.14. Statistical analyses

The Fisher exact test was used to determine statistical significance when comparing the probability of withdrawal between 2 groups. The paired t test was used for comparing the effects of a manipulation to a single control or treated group. A 1-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni multiple comparisons test for comparing the effect of multiple manipulations. A 2-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-tests was utilized for comparing the probability of withdrawal between 2 or more groups over several stimulus intensities. The Wilcoxon match test was used for comparing the response score (ie, intensity of paw withdrawal). All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Significance is indicated in some figures in a table below the graph; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline and sensitized nociceptive behaviors to Aδ stimuli during hind paw inflammation

We first sought to develop the basic parameters for Aδ stimulation and to examine response threshold prior to and during inflammation. In naive animals, the rate of skin heating (Fig. 1A), hind paw withdrawal frequency (Fig. 1B), and intensity of withdrawal reactions (Fig. 1C) increase in parallel with laser-power intensity. The inflection point of the stimulus response function occurs at approximately 3.5 to 4.0 W/mm2 (Fig. 1B). Thus, we designated the range of power below the inflection point as low to moderate intensity, and above it as moderate to high intensity.

Inflaming the hind paw with carrageenan significantly shifted the stimulus-responses curve to the left (Fig. 1D). Note that 2 mg of carrageenan was sufficient to produce hyperalgesia. Conversely, stimulation of the contralateral paw revealed a rightward shift because the animals resisted placing their weight on the inflamed paw (Fig. 1E). To confirm that the hyperalgesic responses to high-energy laser stimulation were initiated by Aδ-fibers rather than sensitized C-fibers, a high-speed camera (500 fps) was used to measure the time needed for evoking nocifensive reactions. The average time to detect laser-evoked movements was 168.5 ± 24.6 ms and 174.0 ± 32.5 ms when stimulating inflamed and noninflamed hind paws, respectively (Fig. 1F). These times fall within the expected range of myelinated TRPV1+ Aδ-fibers whether examining behavior or recording from peripheral nerve or second-order neurons [12,49,80]. The behavioral estimates of Aδ conduction velocity were made with high-speed videography and based on a nerve length of 16.8 cm from toe to dorsal root entry zone dissected from a 350-g rat. Although Aδ-stimulated withdrawal is brisk, and the latency is indistinguishable in inflamed vs naive rats, the duration of both nocifensive guarding and licking behaviors was longer following stimulation of inflamed paws. Stimulation of naive rats at 6W/mm2 caused paw licking for 10.9 ± 1.9 seconds before return to the glass platform, whereas stimulation of the inflamed paw resulted in brief licking followed by prolong continuous guarding totaling 52.9 ± 3.5 seconds off the plate (cut-off 60 seconds; Fig. 1G). Withdrawal latency to C-fiber stimulation was found to be 8.66 ± 0.25 seconds in rats at basal conditions (Fig. 1H). During inflammation, withdrawal latency was significantly shorter, at 4.64 ± 0.43 seconds after 2 mg carrageenan and 3.90 ± 0.86 seconds after 6 mg carrageenan (Fig. 1I), consistent with previous observations of inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia [24,31,39].

3.2. Short Aδ pulse, rapid paw withdrawal, and weight shifting during inflammation

As noted above, an interesting response is seen upon stimulation of the contralateral noninflamed paw. Instead of remaining constant, withdrawal frequency decreases after both doses of carrageenan (Fig. 1E). In addition, these movements are abrupt and vigorous and are qualitatively different from the small movements that occur with the slow C-fiber heat ramp in the context of inflammation. One explanation is that during ongoing inflammation, spinal cord sensory-motor circuits are tonically altered to shift weight toward the uninjured limb, providing postural support to guard the inflamed hind paw. Relatively slower heating paradigms targeting C-fibers (eg, the present test and radiant heat in the Hargreaves test) allow time for postural accommodation, and withdrawal latency on the noninflamed side is unaltered in these tests. We hypothesize that the short 100 ms pulse Aδ stimulus does not afford sufficient time for spinal motor circuits to accommodate a weight shift onto the inflamed hind paw, resulting in increased withdrawal latencies by the noninflamed paw.

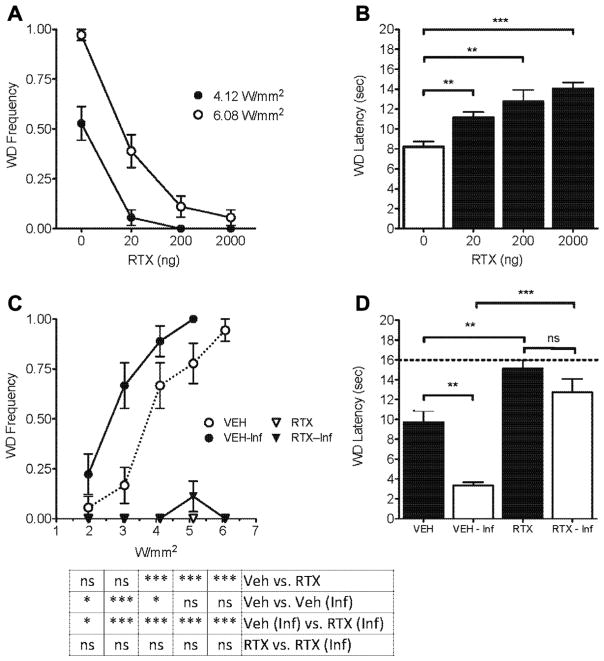

3.3. Loss of hyperalgesic responses following ablation of TRPV1+ fibers by intrathecal administration of RTX to rats

The next set of experiments was designed to examine whether Aδ-initiated behavioral responses that are sensitized by inflammation could be eliminated by pharmacological ablation of TRPV1+ fibers. In noninflamed rats, the acute nocifensive reactions following Aδ stimulation were dose-dependently attenuated by intrathecal- RTX treatment for both moderate (4.12 W/mm2) and high (6.08 W/mm2) intensity Aδ stimulation parameters (Fig. 2A). The withdrawal latency to C-fiber stimulation dose-dependently approached the 16-second cutoff after intrathecal RTX neuronal lesion (Fig. 2B). It is possible that Aδ- and C-fiber nociceptors that express low levels of TRPV1 were not ablated by low-dose (20 and 200 ng) RTX treatment and were therefore capable of providing residual responses to higher intensity (6.08 W/mm2) noxious Aδ thermal stimulation (Fig. 2A). In the next experiment, at 10 days after intrathecal administration of vehicle or 2000 ng RTX, we injected carrageenan into the hind paw. At 24 hours after carrageenan, vehicle-treated inflamed rats demonstrated hyperalgesia to Aδ stimulation, whereas inflamed and noninflamed rats treated with RTX showed virtually no response (Fig. 2C). Following C-fiber stimulation, withdrawal latency was significantly shorter in vehicle- treated rats, suggesting hyperalgesia. In contrast, RTX treatment effectively eliminated inflammatory hyperalgesia (Fig. 2D). Both RTX treatment groups, with and without inflammation, approached the 16-second cutoff, and their withdrawal latencies were significantly increased from their respective vehicle-treated controls (VEH vs RTX, P < 0.01; VEH-Inf vs RTX-Inf, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Effect of intrathecal RTX on withdrawal responses to noxious thermal stimulation. RTX at 20, 200 and 2000 ng was administered intrathecally to ablate the TRPV1+ fibers in the cauda equina and cell bodies in the lumbar ganglia. (A) Paw withdrawal frequency following 2 intensities of Aδ-fiber stimulation in rats 10 days after intrathecal administration of vehicle or RTX (n = 6 rats). Complete suppression of Aδ responses occured with 200 or 2000 ng RTX, depending on stimulus intensity. (B) C-fiber laser stimulation shows a dose-dependent increase in paw-withdrawal latency in RTX-treated rats compared to vehicle (n = 6 rats). (C, D) RTX-induced TRPV1+ fiber ablation significantly attenuates behavioral responses for either (C) Aδ- or (D) C-fiber stimulation of inflamed hind paw compared to the saline-injected contralateral paw (n = 6 rats). The animals were tested within 24 hours after carrageenan injection for (C) Aδ- or (D) C-fiber response.

3.4. Trpv1−/− mice: behavioral responses at baseline compared to RTX-treated wt mice

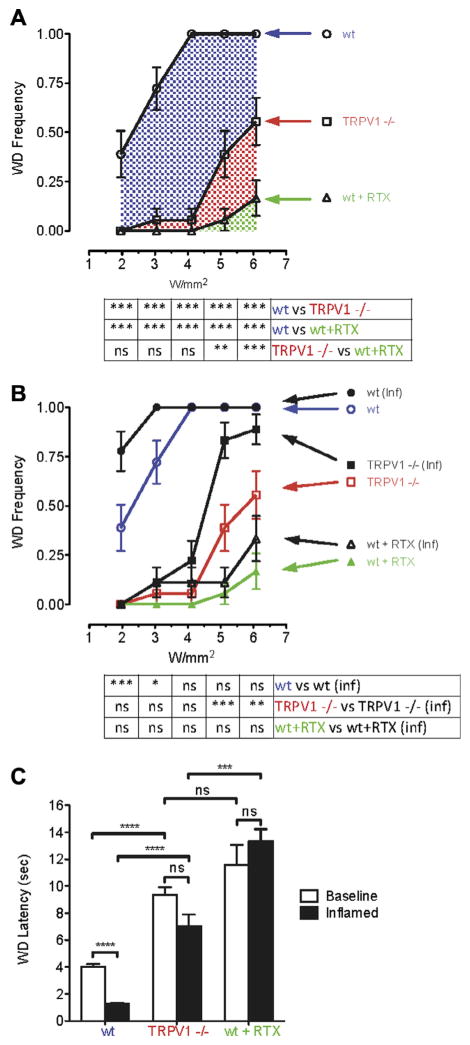

To determine the contribution of TRPV1 receptors to Aδ-evoked responses following noxious thermal stimulation, we evaluated nociceptive behaviors in Trpv1−/− mice. In these animals, the peripheral nerve fibers were intact but lacked this important thermoresponsive ion channel. Responses in the Trpv1−/− mice were compared to wt mice at baseline and after intraplantar injection of RTX. The stimulus-response curve for wt mice reached a plateau at 4W/mm2 with 100% of the mice responding (Fig. 3A). Trpv1−/− mice were largely unresponsive at low to moderate Aδ energy settings (2–4 W/mm2); however, the knockout mice (red label, Fig. 3A) began responding at high intensities (5–6 W/mm2), although less frequently than wt mice. The response to high-intensity stimulation is consistent with the idea of peripheral nerve terminal activation by algesic chemicals such as ATP or bradykinin released from subclinically damaged tissues or blood vessels, respectively, by the higher power pulses. Intraplantar RTX was found to produce profound analgesia. RTX-treated wt mice (green label) remained significantly analgesic up to the highest power settings tested. The blue hatched area in Fig. 3A represents the cumulative response of wt mice above that of Trpv1−/− mice, whereas the blue + red areas represent the response frequency of TRPV1+ fibers before lesion with RTX. The effects in the green area are minor; none of the stimuli delivered to RTX-treated wt mice, even the 6.08 W/mm2 pulse, produced responses that were statistically different from each other. The sporadic responses may be attributed to incomplete deletion of the afferent endings.

Fig. 3.

Trpv1 gene knockout and RTX-mediated TRPV1+ fiber lesion attenuate Aδ nocifensive behavioral responses. (A) Ascending Aδ stimuli (2–6 W/mm2) were applied to plantar surface of uninflamed wt mouse hind paws. Withdrawal frequency plateaued at 100% with a power of 4 W/mm2 (n = 6 mice). Trpv1−/− produced nearly complete reduction at 2, 3, and 4 W/mm2. Attenuated yet significant withdrawal occurred at 5 and 6 W/mm2, suggesting the presence of TRPV1 ion channel independent mechanism(s) for withdrawal at high-intensity stimulations. Removal of the TRPV1 fibers with RTX produced a more complete suppression of withdrawal, even with the 5 and 6 W/mm2 high-intensity stimulations. (B) Aδ-mediated withdrawal frequency in RTX-treated wt and Trpv1−/− mice was determined at baseline and 24 hours postinflammation (n = 6). Inflammation caused a leftward shift in the stimulus response (black lines) compared to noninflamed wt and Trpv1−/− mice, but not in mice treated with RTX. For Trpv1−/− mice, significant sensitization occurred with the high-intensity stimuli (red line). Sensitization to low-intensity stimuli (2–4 W/mm2) was TRPV1 ion channel-dependent. Loss of the TRPV1+ peripheral ending blocked sensitization; however, some residual behavioral responsiveness was detected. (C) Comparison of withdrawal latency in wt, Trpv1−/−, and RTX-treated mice showed that C-fiber behavioral responses were sensitized to inflammation only in wt mice. An elevated withdrawal latency occurred in both Trpv1−/− and RTX-treated wt mice compared to wt mice; both manipulations blocked thermal sensitization (n = 6).

3.5. Trpv1−/− mice, inflammation-induced sensitization compared to RTX-treated wt mice

The ability of peripheral inflammation to sensitize Aδ-evoked responses was explored by comparing wt, Trpv1−/−, and RTX-lesioned mice at 24 hours after carrageenan-induced inflammation (Fig. 3B). Compared to their noninflamed counterparts, inflamed wt mice showed a leftward shift in sensitivity at lower power intensities and reached a plateau of 100% response frequency at moderate and high intensities. At low and moderate Aδ laser intensities (2–4 W/mm2), inflamed Trpv1−/− mice were not significantly different from noninflamed Trpv1−/− mice (Fig. 3B, red line). By comparison, at higher power settings (5–6 W/mm2), the Trpv1−/− mice exhibited significant hyperalgesia, although it was substantially attenuated compared to inflamed wt mice. This suggests that partial sensitization of either the afferent fibers or spinal cord second-order neurons, or both, can occur independent of TRPV1 receptors and may be due to local release of algesic mediators.

The bar graphs in Fig. 3C demonstrate that with C-fiber stimulation parameters, paw-withdrawal latency is significantly decreased during inflammation in wt mice compared to baseline. In contrast, for Trpv1−/− or RTX-treated mice, no significant decrease in withdrawal latency was observed during inflammation, suggesting elimination of C-fiber-mediated inflammatory hyperalgesia in both cases. However, RTX-treated wt mice showed significant increases in withdrawal latency compared to Trpv1−/− mice during inflammation. This observation suggests that pharmacological removal of Trpv1-containing fibers produces more effective thermal analgesia and antihyperalgesia during inflammation than genetic removal of the TRPV1 receptor only.

3.6. TRPV1+ fiber chemoablation, behavioral responses, skin damage, and supramaximal stimuli

We next sought to determine the impact of TRPV1+ fiber chemoablation via peripherally administered RTX on responses to supramaximal laser stimulation. At all Aδ power intensities, vehicle-treated rats responded 100% of the time, but rats treated with 250 ng intraplantar RTX showed minimal nocifensive behaviors (Fig. 4A). Because high power was used, 1 hind paw of 6 rats was stimulated only once at each of 4 laser power settings. In RTX-treated rats, only 2 responses occurred throughout the combined 24 supramaximal Aδ stimulations. In testing the response to C-fiber stimuli, the paw-withdrawal latency in RTX-treated rats was 22.6 ± 6.4 seconds, with some rats reaching the supramaximal threshold of 30 seconds (Fig. 4B). Black circles represent thermally induced skin damage. In mice (Fig. 4C), a strong laser stimulus of 4.46 W/mm2 was fired for 100 ms (nondamaging) or 200 ms (damaging). A difference in RTX-treated mice compared to naive wt mice was observed, but Trpv1−/− mice were not significantly more analgesic than wt mice, suggesting that RTX treatment provides an analgesic effect above that afforded by Trpv1 gene knockout.

To examine the effect of supramaximal stimulation on skin tissue, 250 ng intraplantar RTX was administered to rats anesthetized with isoflurane (2.5%). C-fiber stimuli at a standard intensity of 0.0815 W/mm2 applied for the standard 14-second cutoff duration did not result in tissue damage at 24 hours (Fig. 4D). By comparison, supramaximal duration laser stimulation of 30 seconds resulted in skin damage and neutrophil infiltration within 24 hours (Fig. 4E). Strong 100 ms pulse Aδ stimuli at 5.12 W/mm2 and 6.08 W/mm2 were able to elicit a robust withdrawal response when delivered to the foot. When delivered to the skin on the back, neither power caused perturbation of the underlying skin (Fig. 4F). Increasing the duration produced clinical and subclinical effects. The 200 ms pulse is designated subclinical because it failed to cause overt damage but did stimulate mild neutrophil infiltration. Visible and histologically evident tissue damage occurred upon delivery of a high-energy, long-duration (300 ms) stimulus. Thus, increasing the laser intensity and stimulus time to rats under general anesthesia generated a subclinical effect and then frank skin damage with more pronounced neutrophil infiltration.

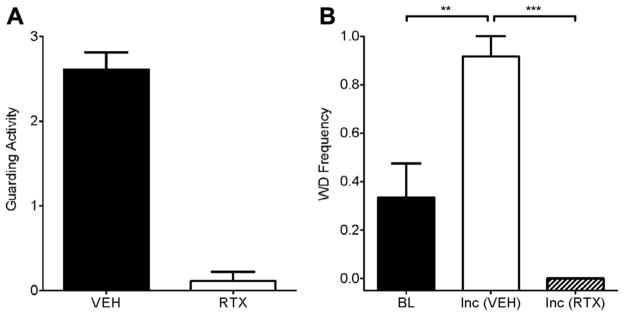

3.7. Incision model

In a rat hind-paw incision model [1], we examined whether Aδ-stimulation elicited guarding behaviors after surgical incision. We also determined whether the guarding behavior was influenced by the presence of TRPV1+ afferent fibers. Following hind-paw incision, rats exhibited robust guarding behaviors at 4 hours that were completely eliminated after treatment with 50 ng intraplantar RTX (Fig. 5A). Following experimental incision, significantly greater withdrawal frequencies were observed after stimulation of Aδ-fibers compared to preincisional rats (Fig. 5B). However, responses to laser stimulation following incision were completely eliminated by intraplantar administration of RTX. These data demonstrate the contribution of Aδ-fibers to the sensitization of withdrawal responses and guarding behavior following experimental incision.

Fig. 5.

Intraplantar RTX eliminates guarding and Aδ-mediated withdrawal behaviors following experimental incision. (A) Incisional injury produces prolonged guarding activity, which is eliminated following intraplantar RTX (250 ng) treatment. (B) Experimental incision (Inc) sensitizes rats to Aδ stimulation (3.5 W/mm2) compared to baseline (n = 6). The hyperalgesic response is reversed by intraplantar RTX.

3.8. Colocalization of TRPV1 with a myelination marker

The presence of myelinated TRPV1+ afferents was examined by double-label immunofluorescence using antibodies to NF200, a neurofilament protein marker of myelinated afferents (Fig. 6A) and TRPV1 (Fig. 6B) in DRG sections. We observed an overall colocalization of the myelination marker in 11.4% of the TRPV1+ population (Fig. 6C). This colocalization represents a composite of neurons that display a range of levels of NF200 and TRPV1, as reported in the figure (Fig. 6D), and our percentage is within the reported range (5%–30%) of colocalization [35,45,52,78]. The immunocytochemical colocalization supports our behavioral data, suggesting that TRPV1 is present in thermosensitive and chemosensitive Aδ-fibers. Additionally, a variable degree of TRPV1 staining is seen in DRG neurons, as evidenced by variation in fluorescence intensity. This range of expression is observable in other studies using immunofluorescent or colorimetric stains. We suggest that the variation in staining reflects a range of TRPV1 expression in these neurons and hypothesize that different levels of expression govern neuronal sensitivity to heat and stimulation or lesion by vanilloid agonists.

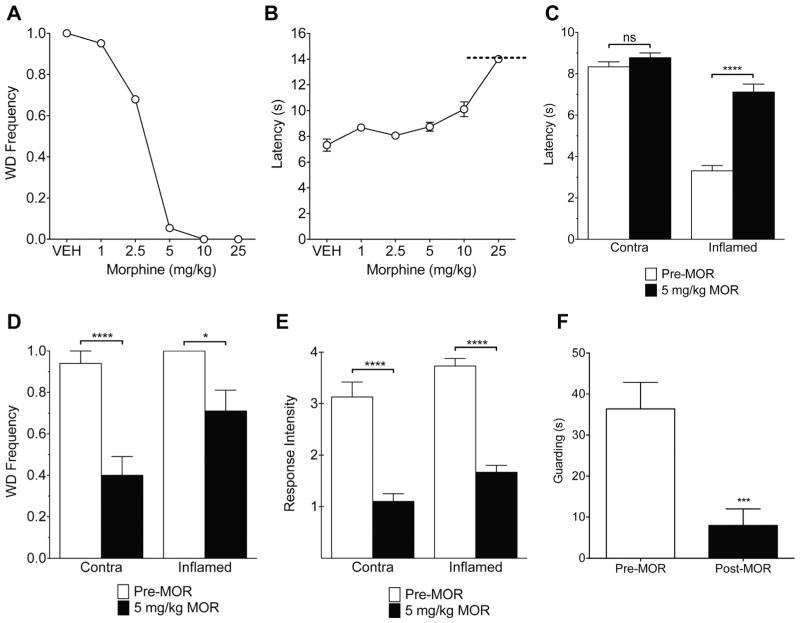

3.9. Morphine attenuates responses to Aδ- and C-fiber stimulation

Opiates are potent analgesics and are commonly used clinically to attenuate inflammatory pain. Therefore, we examined the effects of the μ-opioid agonist morphine on the behavioral responses to Aδ- and C-fiber infrared diode laser stimulation. At baseline, systemic morphine treatment induced a dose-dependent suppression of Aδ responses and an increased withdrawal latency to C-fiber stimulation (Fig. 7A, B). Aδ-initiated responses were nearly completely blocked by 5 mg/kg morphine, whereas withdrawal latency to C-fiber stimulation was not affected at this dose. Morphine at 5 mg/kg significantly reduced inflammatory hyperalgesia to C-fiber stimulation (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, this dose of morphine attenuated the baseline behavioral response to Aδ stimuli and also suppressed Aδ-evoked responses during inflammation. The frequency (Fig. 7D), intensity (Fig. 7E), and guarding time after stimulation (Fig. 7F) were all significantly reduced. These observations suggest that TRPV1+ Aδ fibers are comparatively more sensitive to morphine. However, additional factors, such as differences in fiber density and spatial summation, need to be considered before reaching this conclusion. C-fibers outnumber Aδ fibers in rat paw skin, and the area of the C-fiber stimulus used in this study was substantially larger (−10−) than that of the Aδ stimulus [23,26,29,40,43]. In addition, these data were recorded in awake, unrestrained rats with a noncontact thermal stimulus. The methodological differences, such as suprathreshold and high-intensity stimulus parameters, may yield results that vary from other studies using threshold endpoints, electrical nerve stimulation, or animals under general anesthesia [17–19,43,50,76,77].

Fig. 7.

Effect of systemic morphine on Aδ- and C-fiber responses at baseline and during inflammation. (A) Morphine dose-dependently blocked paw withdrawal to the Aδ stimulus at 5.6 W/mm2. Withdrawal frequency was almost completely inhibited in rats treated with 5 mg/kg morphine (n = 10 rats). (B) The withdrawal latency to C-fiber stimulation at 0.0815 W/mm2 was significantly increased compared to vehicle at the highest dose only, 25 mg/kg (n = 10 rats). The dashed line at 14 seconds represents the trial cut-off to prevent tissue injury. (C) During carrageenan-induced unilateral inflammation, 5 mg/kg morphine reversed thermal hyperalgesia to the C-fiber stimulus without increasing baseline withdrawal latency (ie, producing analgesia) in the contralateral paw (n = 15 rats). With the Aδ stimulus, 5 mg/kg morphine (D) attenuated the withdrawal frequency in inflamed rats, (E) reduced the response intensity, and (F) inhibited Aδ-evoked guarding (n = 15 rats).

4. Discussion

Subsequent to its cloning, numerous cellular and behavioral analyses examined the role of TRPV1 in thermal nociception [9,14,36]. Although thresholds are often an endpoint, we used a broad spectrum of stimulus energies to examine stimulus-response functions, nocifensive behaviors, and anatomical alterations in skin. Additionally, Trpv1−/− mice were compared to RTX-treated wt mice to assess TRPV1 ion channels, per se, vs TRPV1+ afferent fibers in inflammatory and incisional models. The present data show both Aδ- and C-fiber responses are attenuated by Trpv1 knockout or treatment with RTX or morphine.

4.1. Aδ and C-fiber stimuli

We initially established whether TRPV1+ Aδ-fibers contribute to laser-evoked pain behaviors. Previous tail-flick and paw stimulation studies examining laser-evoked cerebral cortical potentials showed that peaks corresponding to Aδ activation were recorded between 60 and 100 ms, whereas C-fiber signals occurred at 250 ms [3,16,19,27,30,65]. Videography shows that Aδ-evoked nocifensive reactions occur as early as 170 ms. Given that 80 to 130 ms are needed for CNS signal processing [3,13,58], impulses responsible for triggering movement by 170 ms in our study appear to reach the cortex well before 100 ms. This is consistent with behavioral responses being driven predominantly by Aδ-fibers, although a contribution from C-fibers at the behavioral endpoint cannot be completely discounted. Conversely, as the slowly increasing C-fiber stimulus reaches temperatures that open TRPV1 and drive C-fiber firing, some contribution from TRPV1+ Aδ fibers cannot be excluded [49,60].

4.2. Aδ activation and central sensitization: a perspective on breakthrough pain

During peripheral inflammation, hyperalgesia to both Aδ- and C-fiber stimulation occurs, but the behavioral responses are notably different. C-fiber stimulation of the inflamed paw produces an early, although motorically weak, limb withdrawal at −3 seconds, frequently accompanied by brief paw licking. By comparison, Aδ stimulation results in brisk and vigorous withdrawal of the inflamed paw followed by evident licking and prolonged elevation. The intensity of paw movement is nearly identical to that of the noninflamed paw, suggesting Aδ stimulation is sufficient to override ongoing tendencies to guard the inflamed paw. Because noxious laser pulses can also activate C-fibers [56], we cannot distinguish whether the prolonged guarding is mediated by activation of Aδ or C-fibers, or both. Ongoing C-fiber activity can induce central sensitization [37], and in such cases a laser-evoked Aδ volley may trigger prolonged after-responses in central circuits. This interplay between afferent fiber types and central sensitization suggests that TRPV1+ Aδ fibers, in addition to mechanoreceptive Aδ fibers, may contribute to phenomena such as breakthrough pain (BTP) [55,59]. This is a distressing exacerbation of ongoing pain that can overcome physiological and maintenance levels of pharmacological inhibition [15,47,66]. Current treatment of BTP commonly involves supplementation with rapidly absorbed opioids [15,47,66], and we show that Aδ responses are particularly sensitive to morphine. Additionally, the participation of TRPV1+ Aδ fibers suggests a vanilloid-based, non-opioid alternative for treatment of BTP [6].

4.3. RTX lesion of TRPV1+ fibers and variation of TRPV1 expression

Intrathecal injection of RTX produces dose-dependent decreases in withdrawal frequency and increases in withdrawal latency to Aδ- and C-fiber stimulation, respectively (Fig. 2A, B). Moderate to intense Aδ laser stimuli were used to explore the completeness of the RTX lesion. At 4.12 W/mm2, 20 ng RTX yielded complete suppression of withdrawal, whereas at 6.08 W/mm2, the 20 ng dose is −60% effective. Increasing the intrathecal RTX dose nearly completely eliminated responses to Aδ stimuli in normal or inflamed rats (Fig. 2A, C). The variation in TRPV1 levels seen in DRG neurons using immunocytochemistry (Fig. 6) [35,79] may contribute to the differential sensitivity of individual fibers to both heat and RTX-induced deactivation. Differential TRPV1 expression has important implications for the therapeutic use of TRPV1 agonists. Incomplete destruction may produce only a partial cellular loss or temporary conduction defect that allows nerve endings, axons, or perikarya [34,49] that express low amounts of TRPV1 to be more resistant to RTX. Clinically, an initial complete inhibition may gradually diminish as low TRPV1-expressing fibers, which may be only partially compromised, slowly become repaired, thereby leading to a resumption of chronic pain. In these cases, readministration of RTX may be necessary to achieve adequate analgesia.

In contrast to intrathecal injections, intraplantar injection of high doses of RTX blocked nociceptive transmission so profoundly that behavioral responses were absent, even to frankly damaging thermal stimuli (Fig. 4). Earlier studies suggested that behavioral responses in the absence of TRPV1 receptors were mediated by thermal activation of TRPV2, but results from Trpv1-Trpv2 double-knockout mice and other experimental paradigms do not support a thermo-responsive role for TRPV2 in vivo [36,57]. Residual physiological and behavioral responses to tissue-damaging temperatures likely involve receptors from the ASIC and P2X families expressed on TRPV1+ fibers [11,68,71,74]. The loss of responses after intraplantar RTX, with or without ongoing inflammation, is consistent with the idea that residual transduction mediated by local release of neuroactive chemicals is also lost in the absence of TRPV1+ fibers [21,36,46,48]. The additional efficacy of RTX suggests that the intraplantar compartment confined the drug solution enough to produce a more complete lesion and provides a template for clinical application.

The range of TRPV1 expression [35,45,52,79] may be relevant to earlier neurophysiological classification of thermosensing Aδ fibers in primates [69]. High heat threshold type I fibers (>53 °C and capsaicin insensitive) may represent the very lowest-expressing TRPV1+ DRG neurons, whereas type II Aδ fibers (heat threshold −46 °C and capsaicin sensitive) express higher levels of TRPV1. An additional consideration is that differential regulatory processes for controlling TRPV1 activation may be present in the different fiber types to control firing thresholds. We speculate that the higher threshold of Aδ fibers and their dependence on a rapid rate of rise of thermal stimuli compared to C-fibers [76,77] is a mechanism for preventing unnecessary or incidental activation of Aδ fibers. Thus, abrupt Aδ-mediated withdrawal responses can be reserved for strong, acute nociceptive stimuli that utilize the Aδ channel of communication.

4.4. Nocifensive responses after Trpv1 gene knockout compared to removal of TRPV1+ fibers

TRPV1 plays a major role in triggering nocifensive behaviors in inflammatory states; however, few studies directly compare the contribution of TRPV1 receptors to the TRPV1+ fibers expressing them. We observe that Trpv1 gene knockout reduces nociceptive responses at low to moderate Aδ intensities (2–4 W/mm2), but sensitivity at higher intensities (5–6 W/mm2), although blunted, is retained. In contrast, RTX causes nearly complete suppression of withdrawal behaviors to Aδ stimuli over the entire range of power intensities tested. RTX was also effective in the surgical incision model where Aδ-mediated thermal hyperalgesia and increased guarding activity are eliminated by local RTX injection. These data suggest several practical advantages to local use of RTX. While loss of heat- and inflammation-related sensations occurs in treated dermatomes, noxious thermal sensations at other body sites are preserved, suggesting that strong, locally focused chemical excision of TRPV1+ afferent endings can provide robust analgesia in many painful conditions [25]. In contrast, manipulations targeting only TRPV1 (eg, gene knockout or capsaicin antagonists) appear to be only partially effective in producing analgesia. Partial efficacy also is observed in animal and human pain models that do not rely on thermally evoked responses. For example, TRPV1 blockade is efficacious in monoiodoacetate-induced osteoarthritis, at early time points with less severe joint impairment compared to later times when the disorder is more severe [55]. In human third molar extraction, the duration of TRPV1 antagonist analgesia lasted −90 minutes and waned as the postsurgical inflammation progressed, even though drug blood levels and receptor blockade were maintained [62]. Thus, despite high potency, specificity and effective target engagement, it appears that multiple factors can counteract TRPV1 antagonist-mediated analgesia.

Morphine attenuates hyperalgesia to infrared laser stimulation. Opiates are frequently used to treat inflammatory and postsurgical pain. The present data illustrate that morphine dose-dependently inhibits responses to Aδ- and C-fiber stimulation. Morphine appears to act more potently on Aδ- than C-fibers in control animals in agreement with previous studies [33,43,44]. During carrageenan-induced hind-paw inflammation, morphine attenuated both Aδ- and C-fiber-mediated hyperalgesia and guarding (Fig. 7C, E, F). These in vivo results are consistent with in vitro spinal cord slice studies demonstrating Aδ-fiber activation of nociresponsive second-order neurons, enhanced responses following inflammation, and reduction of Aδ-mediated field potentials by morphine [50,63,64,67,72]. The presence of μ-opioid receptors on TRPV1+ DRG neurons [18] and colocalization of TRPV1 in subpopulations of Aδ neurons are consistent with the sensitivity of Aδ neurons to pharmacological doses of morphine [23]. These data suggest that μ-opioid-containing TRPV1+ Aδ neurons may contribute to a variety of chronic pain problems [6,15,23,31,49,55,79].

4.5. Conclusions

Of the 3 approaches targeting TRPV1, antagonists, agonists, and positive allosteric modulators [20,22,39], only the latter 2 affect TRPV1+ fiber integrity; hence, all of the receptors on the nerve terminal, rather than blocking a single receptor. The present data suggest that TRPV1 agonist dose, route of administration, density of receptors, and distribution among fiber types are important covariates influencing optimal pharmacological responses. Although we characterize Aδ- and C-fibers behaviorally, these studies also highlight the need for cell-specific molecular markers to define Aδ subpopulations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, and by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health. We thank Brian Bates for his expert technical assistance in parts of this work.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Banik RK, Brennan TJ. Trpv1 mediates spontaneous firing and heat sensitization of cutaneous primary afferents after plantar incision. PAIN®. 2009;141:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beitel RE, Dubner R, Harris R, Sumino R. Role of thermoreceptive afferents in behavioral reaction times to warming temperature shifts applied to the monkeys face. Brain Res. 1977;138:328–46. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90750-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benoist JM, Pincede I, Ballantyne K, Plaghki L, Le Bars D. Peripheral and central determinants of a nociceptive reaction: an approach to psychophysics in the rat. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bessou P, Perl ER. Response of cutaneous sensory units with unmyelinated fibers to noxious stimuli. J Neurophysiol. 1969;32:1025–43. doi: 10.1152/jn.1969.32.6.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhave G, Zhu W, Wang H, Brasier DJ, Oxford GS, Gereau RW., 4th cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulates desensitization of the capsaicin receptor (VR1) by direct phosphorylation. Neuron. 2002;35:721–31. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00802-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brederson JD, Chu KL, Reilly RM, Brown BS, Kym PR, Jarvis MF, McGaraughty S. TRPV1 antagonist, A-889425, inhibits mechanotransmission in a subclass of rat primary afferent neurons following peripheral inflammation. Synapse. 2012;66:187–95. doi: 10.1002/syn.20992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown DC, Iadarola MJ, Perkowski SZ, Hardem E, Shofer F, Karai L, Olah Z, Mannes AJ. Physiologic and antinociceptive effects of intrathecal resiniferatoxin in a canine bone cancer model. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1052–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200511000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bushnell MC, Taylor MB, Duncan GH, Dubner R. Discrimination of innocuous and noxious thermal stimuli applied to the face in human and monkey. Somatosens Res. 1983;1:119–28. doi: 10.3109/07367228309144544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–13. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–24. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CC, Wong CW. Neurosensory mechanotransduction through acid-sensing ion channels. J Cell Mol Med. 2013;17:337–49. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuellar JM, Manering NA, Klukinov M, Nemenov MI, Yeomans DC. Thermal nociceptive properties of trigeminal afferent neurons in rats. Mol Pain. 2010;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danneman PJ, Kiritsy-Roy JA, Morrow TJ, Casey KL. Central delay of the laseractivated rat tail-flick reflex. PAIN®. 1994;58:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90183-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis JB, Gray J, Gunthorpe MJ, Hatcher JP, Davey PT, Overend P, Harries MH, Latcham J, Clapham C, Atkinson K, Hughes SA, Rance K, Grau E, Harper AJ, Pugh PL, Rogers DC, Bingham S, Randall A, Sheardown SA. Vanilloid receptor-1 is essential for inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia. Nature. 2000;405:183–7. doi: 10.1038/35012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis MP. Recent development in therapeutics for breakthrough pain. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10:757–73. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devor M, Carmon A, Frostig R. Primary afferent and spinal sensory neurons that respond to brief pulses of intense infrared laser radiation: a preliminary survey in rats. Exp Neurol. 1982;76:483–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(82)90118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickenson AH, Sullivan AF. Electrophysiological studies on the effects of intrathecal morphine on nociceptive neurones in rat dorsal horn. PAIN®. 1986;24:211–22. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endres-Becker J, Heppenstall PA, Mousa SA, Labuz D, Oksche A, Schafer M, Stein C, Zollner C. Mu-opioid receptor activation modulates transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) currents in sensory neurons in a model of inflammatory pain. Molec Pharmacol. 2007;71:12–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan RJ, Kung JC, Olausson BA, Shyu BC. Nocifensive behaviors components evoked by brief laser pulses are mediated by C fibers. Physiol Behav. 2009;98:108–17. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrer-Montiel A, Fernandez-Carvajal A, Planells-Cases R, Fernandez-Ballester G, Gonzalez-Ros JM, Messeguer A, Gonzalez-Muniz R. Advances in modulating thermosensory TRP channels. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2012;22:999–1017. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.711320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greffrath W, Nemenov MI, Schwarz S, Baumgartner U, Vogel H, Arendt-Nielsen L, Treede RD. Inward currents in primary nociceptive neurons of the rat and pain sensations in humans elicited by infrared diode laser pulses. PAIN®. 2002;99:145–55. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haanpaa M, Treede RD. Capsaicin for neuropathic pain: linking traditional medicine and molecular biology. Eur Neurol. 2012;68:264–75. doi: 10.1159/000339944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinke B, Gingl E, Sandkuhler J. Multiple targets of mu-opioid receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition at primary afferent Adelta- and C-fibers. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1313–22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4060-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iadarola MJ, Brady LS, Draisci G, Dubner R. Enhancement of dynorphin gene expression in spinal cord following experimental inflammation: stimulus specificity, behavioral parameters and opioid receptor binding. PAIN®. 1988;35:313–26. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iadarola MJ, Gonnella GL. Resiniferatoxin for pain treatment: an interventional approach to personalized pain medicine. Open Pain J. 2013;6:95–107. doi: 10.2174/1876386301306010095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikoma M, Kohno T, Baba H. Differential presynaptic effects of opioid agonists on Adelta- and C-afferent glutamatergic transmission to the spinal dorsal horn. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:807–12. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000286985.80301.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isseroff RG, Sarne Y, Carmon A, Isseroff A. Cortical potentials evoked by innocuous tactile and noxious thermal stimulation in the rat: differences in localization and latency. Behav Neural Biol. 1982;35:284–307. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(82)90725-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain A, Bronneke S, Kolbe L, Stab F, Wenck H, Neufang G. TRP-channel-specific cutaneous eicosanoid release patterns. PAIN®. 2011;152:2765–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jurna I, Heinz G. Differential effects of morphine and opioid analgesics on A and C fibre-evoked activity in ascending axons of the rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1979;171:573–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)91065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalliomaki J, Weng HR, Nilsson HJ, Schouenborg J. Nociceptive C fibre input to the primary somatosensory cortex (SI): a field potential study in the rat. Brain Res. 1993;622:262–70. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90827-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karai L, Brown DC, Mannes AJ, Connelly ST, Brown J, Gandal M, Wellisch OM, Neubert JK, Olah Z, Iadarola MJ. Deletion of vanilloid receptor 1-expressing primary afferent neurons for pain control. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1344–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI20449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaszas K, Keller JM, Coddou CA, Mishra SK, Hoon MA, Stojilkovic S, Jacobson KA, Iadarola MJ. Small molecule positive allosteric modulation of TRPV1 activation by vanilloids and acidic pH. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340:152–60. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.183053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimura S, Honda M, Tanabe M, Ono H. Noxious stimuli evoke a biphasic flexor reflex composed of A delta-fiber-mediated short-latency and C-fiber-mediated long-latency withdrawal movements in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95:94–100. doi: 10.1254/jphs.95.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kissin I, Freitas CF, Bradley EL. Perineural resiniferatoxin prevents the development of hyperalgesia produced by loose ligation of the sciatic nerve in rats. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:1210–6. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000260296.01813.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi K, Fukuoka T, Obata K, Yamanaka H, Dai Y, Tokunaga A, Noguchi K. Distinct expression of TRPM8, TRPA1, and TRPV1 mRNAs in rat primary afferent neurons with adelta/c-fibers and colocalization with trk receptors. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:596–606. doi: 10.1002/cne.20794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koerber HR, McIlwrath SL, Lawson JJ, Malin SA, Anderson CE, Jankowski MP, Davis BM. Cutaneous C-polymodal fibers lacking TRPV1 are sensitized to heat following inflammation, but fail to drive heat hyperalgesia in the absence of TRPV1 containing C-heat fibers. Mol Pain. 2010;6:58. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain. 2009;10:895–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawson JJ, Mcllwrath SL, Woodbury CJ, Davis BM, Koerber HR. TRPV1 unlike TRPV2 is restricted to a subset of mechanically insensitive cutaneous nociceptors responding to heat. J Pain. 2008;9:288–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lebovitz EE, Keller JM, Kominsky H, Kaszas K, Maric D, Iadarola MJ. Positive allosteric modulation of TRPV1 as a novel analgesic mechanism. Molec Pain. 2012;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leem JW, Willis WD, Chung JM. Cutaneous sensory receptors in the rat foot. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:1684–99. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.5.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang DY, Li X, Li WW, Fiorino D, Qiao Y, Sahbaie P, Yeomans DC, Clark JD. Caspase-1 modulates incisional sensitization and inflammation. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:945–56. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ee2f17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu PL, Hsu SS, Tsai ML, Jaw FS, Wang AB, Yen CT. Temporal and spatial temperature distribution in the glabrous skin of rats induced by short-pulse CO2 laser. J Biomed Optics. 2012;17:117002. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.11.117002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu Y, Pirec V, Yeomans DC. Differential antinociceptive effects of spinal opioids on foot withdrawal responses evoked by C fibre or A delta nociceptor activation. Brit J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1210–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu Y, Sweitzer SM, Laurito CE, Yeomans DC. Differential opioid inhibition of Cand A delta-fiber mediated thermonociception after stimulation of the nucleus raphe magnus. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:414–9. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000094334.12027.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma QP. Expression of capsaicin receptor (VR1) by myelinated primary afferent neurons in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002;319:87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02537-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M. Novel classes of nociceptors: beyond Sherrington. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:199–201. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mercadante S, Villari P, Ferrera P, Mangione S, Casuccio A. The use of opioids for breakthrough pain in acute palliative care unit by using doses proportional to opioid basal regimen. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:306–9. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181c4458a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michaelis M, Habler HJ, Jaenig W. Silent afferents: a separate class of primary afferents? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1996;23:99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb02579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitchell K, Bates BD, Keller JM, Lopez M, Scholl L, Navarro J, Madian N, Haspel G, Nemenov MI, Iadarola MJ. Ablation of rat TRPV1-expressing Adelta/C-fibers with resiniferatoxin: analysis of withdrawal behaviors, recovery of function and molecular correlates. Molec Pain. 2010;6:94. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monconduit L, Bourgeais L, Bernard JF, Villanueva L. Systemic morphine selectively depresses a thalamic link of widespread nociceptive inputs in the rat. Eur J Pain. 2002;6:81–7. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ng LG, Qin JS, Roediger B, Wang Y, Jain R, Cavanagh LL, Smith AL, Jones CA, de Veer M, Grimbaldeston MA, Meeusen EN, Weninger W. Visualizing the neutrophil response to sterile tissue injury in mouse dermis reveals a three-phase cascade of events. J Invest Derm. 2011;131:2058–68. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Niiyama Y, Kawamata T, Yamamoto J, Omote K, Namiki A. Bone cancer increases transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 expression within distinct subpopulations of dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience. 2007;148:560–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Numazaki M, Tominaga T, Toyooka H, Tominaga M. Direct phosphorylation of capsaicin receptor VR1 by protein kinase Cepsilon and identification of two target serine residues. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13375–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Neill J, Brock C, Olesen AE, Andresen T, Nilsson M, Dickenson AH. Unravelling the mystery of capsaicin: a tool to understand and treat pain. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:939–71. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.006163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okun A, Liu P, Davis P, Ren J, Remeniuk B, Brion T, Ossipov MH, Xie J, Dussor GO, King T, Porreca F. Afferent drive elicits ongoing pain in a model of advanced osteoarthritis. PAIN®. 2012;153:924–33. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pareek TK, Keller J, Kesavapany S, Agarwal N, Kuner R, Pant HC, Iadarola MJ, Brady RO, Kulkarni AB. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 modulates nociceptive signaling through direct phosphorylation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:660–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609916104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park U, Vastani N, Guan Y, Raja SN, Koltzenburg M, Caterina MJ. TRP vanilloid 2 knock-out mice are susceptible to perinatal lethality but display normal thermal and mechanical nociception. J Neurosci. 2011;31:11425–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1384-09.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pincede I, Pollin B, Meert T, Plaghki L, Le Bars D. Psychophysics of a nociceptive test in the mouse: ambient temperature as a key factor for variation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Portenoy RK, Hagen NA. Breakthrough pain: definition, prevalence and characteristics. PAIN®. 1990;41:273–81. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90004-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pribisko AL, Perl ER. Use of a near-infrared diode laser to activate mouse cutaneous nociceptors in vitro. J Neurosci Methods. 2011;194:235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Price DD, Dubner R. Neurons that subserve the sensory-discriminative aspects of pain. PAIN®. 1977;3:307–38. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90063-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Quiding H, Jonzon B, Svensson O, Webster L, Reimfelt A, Karin A, Karlsten R, Segerdahl M. TRPV1 antagonistic analgesic effect: a randomized study of AZD1386 in pain after third molar extraction. PAIN®. 2013;154:808–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Differential actions of spinal analgesics on monoversus polysynaptic Adelta-fibre-evoked field potentials in superficial spinal dorsal horn in vitro. PAIN®. 2000;88:97–108. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schomburg ED, Steffens H, Dibaj P, Sears TA. Major contribution of Adelta-fibres to increased reflex transmission in the feline spinal cord during acute muscle inflammation. Neurosci Res. 2012;72:155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun JJ, Yang JW, Shyu BC. Current source density analysis of laser heat-evoked intra-cortical field potentials in the primary somatosensory cortex of rats. Neuroscience. 2006;140:1321–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Svendsen KB, Andersen S, Arnason S, Arner S, Breivik H, Heiskanen T, Kalso E, Kongsgaard UE, Sjogren P, Strang P, Bach FW, Jensen TS. Breakthrough pain in malignant and non-malignant diseases: a review of prevalence, characteristics and mechanisms. Eur J Pain. 2005;9:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Torsney C. Inflammatory pain unmasks heterosynaptic facilitation in lamina I neurokinin 1 receptor-expressing neurons in rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5158–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6241-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Toulme E, Tsuda M, Khakh BS, Inoue K. On the role of ATP-gated P2X receptors in acute, inflammatory and neuropathic pain. In: Kruger L, Light AR, editors. Translational pain research: From mouse to man. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Treede RD, Meyer RA, Raja SN, Campbell JN. Evidence for two different heat transduction mechanisms in nociceptive primary afferents innervating monkey skin. J Physiol. 1995;483:747–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tzabazis A, Klyukinov M, Manering N, Nemenov MI, Shafer SL, Yeomans DC. Differential activation of trigeminal C or Adelta nociceptors by infrared diode laser in rats: behavioral evidence. Brain Res. 2005;1037:148–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ugawa S, Ueda T, Yamamura H, Shimada S. In situ hybridization evidence for the coexistence of ASIC and TRPV1 within rat single sensory neurons. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;136:125–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang C, Chakrabarti MK, Whitwam JG. Effect of low and high concentrations of alfentanil administered intrathecally on A delta and C fibre mediated somatosympathetic reflexes. Brit J Anaesth. 1992;68:503–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/68.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Woodbury CJ, Zwick M, Wang SY, Lawson JJ, Caterina MJ, Koltzenburg M, Albers KM, Koerber HR, Davis BM. Nociceptors lacking TRPV1 and TRPV2 have normal heat responses. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6410–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1421-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu JX, Xu MY, Miao XR, Lu ZJ, Yuan XM, Li XQ, Yu WF. Functional upregulation of P2X3 receptors in dorsal root ganglion in a rat model of bone cancer pain. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:1378–88. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xing BM, Yang YR, Du JX, Chen HJ, Qi C, Huang ZH, Zhang Y, Wang Y. Cyclindependent kinase 5 controls TRPV1 membrane trafficking and the heat sensitivity of nociceptors through KIF13B. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14709–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1634-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yeomans DC, Pirec V, Proudfit HK. Nociceptive responses to high and low rates of noxious cutaneous heating are mediated by different nociceptors in the rat: behavioral evidence. PAIN®. 1996;68:133–40. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yeomans DC, Proudfit HK. Nociceptive responses to high and low rates of noxious cutaneous heating are mediated by different nociceptors in the rat: electrophysiological evidence. PAIN®. 1996;68:141–50. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu L, Yang F, Luo H, Liu FY, Han JS, Xing GG, Wan Y. The role of TRPV1 in different subtypes of dorsal root ganglion neurons in rat chronic inflammatory nociception induced by complete Freund’s adjuvant. Mol Pain. 2008;4:61. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zakir HM, Mostafeezur RM, Suzuki A, Hitomi S, Suzuki I, Maeda T, Seo K, Yamada Y, Yamamura K, Lev S, Binshtok AM, Iwata K, Kitagawa J. Expression of TRPV1 channels after nerve injury provides an essential delivery tool for neuropathic pain attenuation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang J, Cavanaugh DJ, Nemenov MI, Basbaum AI. The modality-specific contribution of peptidergic and non-peptidergic nociceptors is manifest at the level of dorsal horn nociresponsive neurons. J Physiol. 2013;591:1097–110. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.242115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]