Abstract

Making drug development a more efficient and cost-effective process will have a transformative effect on human health. A key, yet underutilized, tool to aid in this transformation is mechanistic computational modeling. By incorporating decades of hard-won prior knowledge of molecular interactions, cellular signaling, and cellular behavior, mechanistic models can achieve a level of predictiveness that is not feasible using solely empirical characterization of drug pharmacodynamics. These models can integrate diverse types of data from cell culture and animal experiments, including high-throughput systems biology experiments, and translate the results into the context of human disease. This provides a framework for identification of new drug targets, measurable biomarkers for drug action in target tissues, and patient populations for which a drug is likely to be effective or ineffective. Additionally, mechanistic models are valuable in virtual screening of new therapeutic strategies, such as gene or cell therapy and tissue regeneration, identifying the key requirements for these approaches to succeed in a heterogeneous patient population. These capabilities, which are distinct from and complementary to those of existing drug development strategies, demonstrate the opportunity to improve success rates in the drug development pipeline through the use of mechanistic computational models.

Keywords: Mechanistic computational model, systems pharmacology, drug development, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics

Graphical Abstract

Current Strategies for Drug Development

It is well established that traditional drug development is a long and increasingly costly process, due in large part to high attrition of drugs throughout the development pipeline [1, 2]. As of 2010, the estimated cost to develop a single new molecular entity (novel active ingredient) was $1.8 billion dollars [3]. In addition, only about 5–6 mechanistically innovative (first-in-class) drugs are approved in the US per year [3, 4]. The most common reasons for drug failure, particularly in Phase 2 trials, are lack of efficacy and toxicity due to off-target drug effects, which were not apparent in cellular and animal systems [5–7]. A better understanding of potential drug targets and mechanisms of action promises to aid in earlier identification of ineffective drugs, or drugs with unsafe off-target effects, as well as to inform the necessary properties (e.g. precise targets and binding affinities) for more effective compounds.

Traditionally, drug efficacy and safety are assayed by characterizing the pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of the drug. PK describes what the body does to a drug (e.g. drug absorption, clearance, and distribution throughout the body), while PD characterizes what a drug does to the body (i.e. drug action in target tissue). Drug PK and PD are typically estimated using a combination of cell culture and animal models, along with human data for similar, previously-developed drugs. This empirical PK and PD characterization allows drug developers to estimate drug half-life in the body and uptake within tissues. Computational models incorporating both PK and PD (PK/PD models) are used to simulate drug distribution in the body, predicting the time delay from administration to drug action in the target tissue, and potential issues such as drug accumulation leading to toxicity. As such, these simulations have the potential to aid in establishing safety margins [8]. While PK/PD work is a critical component of drug development, traditional PK/PD studies do not identify the most effective targets for new drugs, or account for complex biological compensation mechanisms. This lack of predictiveness is a result of the data-driven nature of these studies, which makes extrapolation to other dosing ranges or to related drugs, as well as prediction of patient-specific responses, difficult. The missing piece is a detailed understanding of the molecular mechanisms of action underlying pharmacodynamic responses. Mechanistic models (Box 1) can incorporate this understanding into PK/PD models.

Box 1. What is a mechanistic computational model?

A mechanistic computational model simulates interactions between the key molecular entities (e.g. proteins, ATP, RNA), and the processes they undergo (e.g. expression, subcellular trafficking, degradation, phosphorylation, deactivation), explicitly by solving a set of mathematical equations that represent the underlying chemical reactions (e.g. [A]+[B]⇄[A·B]). The key distinguishing feature of a mechanistic model is incorporation of detail based on prior knowledge of the regulatory network, as opposed to inferring interactions using a data-driven approach.

The sequencing of the human genome brought hope that newly identified genetic components of health and disease would clearly guide advances in therapies for a wide variety of conditions. While bioinformatics approaches have identified new therapeutic targets for some diseases, in many cases there is no clear disease-associated genetic signature that is consistent across patients. Even when a disease-related molecule is identified, it does not necessarily represent an effective drug target; thus far, target-based screening has not been more effective than traditional phenotypic drug screening [9]. As such, many researchers interested in drug development have turned to systems biology, which combines high-throughput experiments and mechanistic computational modeling to better understand the interactions of the molecules that regulate cell behavior.

Systems biology approaches have deepened our understanding of the pathways involved in cellular survival & behavior, and how cellular signaling changes in disease [10]. One particularly valuable benefit of mechanistic computational models is their ability to incorporate the specifics of different experimental protocols (e.g. drug/ligand concentration, measurement time, cell line), allowing for reconciliation of apparent discrepancies in experimental results from different groups, protocols, or cell types. Along with deriving more insight from experimental results, these models can be used to design the next sets of experiments, in order to answer key unsolved questions. A second key strength of mechanistic computational models is the ability to examine the sensitivity of individual signaling pathway components to perturbation (e.g. change in receptor expression or ligand concentration). Proteins to which the model is highly sensitive likely represent key nodes and promising drug targets. Despite these advantages, translation of systems biology into the context of the human body for use in the drug development pipeline has been limited [5, 11], due in part to the prevalence of empirical PK/PD modeling in industry, while mechanistic computational modeling occurs primarily in academic research laboratories (with some notable exceptions).

The emerging field of systems pharmacology aims to bridge systems biology and PK/PD modeling, translating the mechanistic insight emerging from systems biology into a therapeutically relevant context [12, 13]. To do this, mechanistic models (Box 1) are used to describe the pharmacodynamics in quantitative detail, and are integrated with drug pharmacokinetics in a PK/PD model. Several excellent examples of systems pharmacology models incorporating mechanistic intracellular signaling detail have been published in recent years [12, 14, 15]. However, such models remain the minority; it is more common for drug pharmacodynamics to be represented by empirical drug-tissue binding curves (e.g. Hill equation) [16, 17]. While useful, such data-driven binding curves have limited ability to reliably extrapolate to other species, to humans with different genetics and body mass, to related drugs, to combination therapies, or even to different dosing schedules and administration routes for the same drug [11]. One reason for a semi-mechanistic representation of PD in many models to date is a lack of sufficient mechanistic information available from experiments. While this is a challenge, the amount of useful information increases quickly, e.g. due to high-throughput experiments using new molecular imaging and gene expression measurement techniques [18–20]. Additionally, because computational models can integrate diverse data types into a single framework, data from experiments designed for very different purposes, or obtained from different groups using different protocols, can be leveraged [21]. For example, in our PK/PD models, the geometric parameters for the PK component are obtained from histological studies, while the PD are based on a combination of binding assays, receptor trafficking studies, and measurements of receptor phosphorylation under different conditions, from experiments performed in multiple cells lines by different research groups [22, 23].

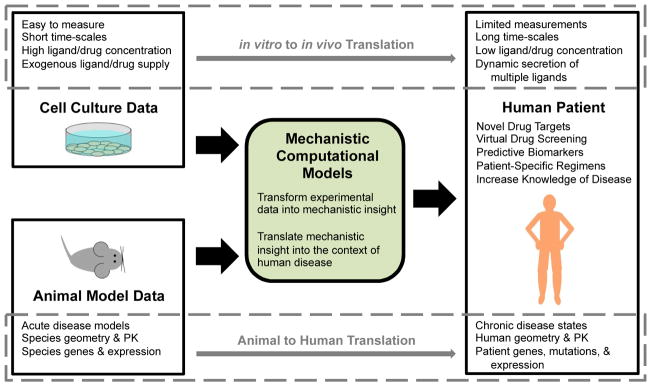

One of the areas where systems pharmacology holds the most promise is in accounting for changes in PK and PD between animal models and humans, both due to geometric differences, and to species-specific genes and gene expression patterns (Fig. 1) [13]. Detailed systems pharmacology models can be built and validated using in vitro data and pharmacokinetic studies in animals, and then converted into human- and disease-specific models [10, 24]. In order for these models to make clinically-relevant predictions, they must then be validated against human data to the maximum extent possible. While human data is limited, levels of drug and other biomarkers in plasma can be measured with relative ease. Mechanistically-detailed systems pharmacology models can then connect predictions of important but difficult-to-measure quantities, such as drug concentration, occupancy of receptors with drug versus native ligand, and cellular signaling at the target site, to measureable biomarkers [10]. By providing a window into the site of disease, these models have great promise to improve our understanding of both disease and therapy in the human body.

Fig 1. Mechanistic computational models bridge gaps in translation.

Due to the difficulty and invasiveness of obtaining direct human measurements of disease and drug action, we often rely on data from other systems. However, translating experimental results from cell culture and animal models into useful predictions in human patients is difficult (dashed boxes). Experimental conditions in cell culture (top) do not match the in vivo site of drug action. Similarly, there is mismatch between animal models (bottom) and human patients. Mechanistic computational models can explicitly account for these differences, integrating data from diverse sources into a single framework, and providing mechanistic insight into drug action. Human disease-specific computational models (PK/PD of the whole body or 3D models or particular tissues) can then be used to predict the effects of drugs in human patients, incorporating patient-specific information (e.g. genetic mutations and gene expression changes).

In light of the capabilities of mechanistic computational models (Box 2), we propose that inclusion of detailed mechanistic information into pharmacodynamic models is critical to understand drug PD in an insightful and predictive way. We present three brief examples where inclusion of mechanistic detail was necessary to: (1) meaningfully discriminate between effective and ineffective drugs, (2) identify promising new drug targets, or (3) understand why existing therapeutic approaches have been ineffective. We chose case studies that focus on mechanistic modeling of receptors and channels, as they are subject to complex regulation, but provide targets more specific than downstream signaling pathways, which are common to many cellular processes. These examples involve different biological systems, highlight different advantages of mechanistic models, and use different techniques to translate the mechanistic insight into the human body. All, however, demonstrate the promise of mechanistic computational models to aid in drug development for a wide range of diseases (Box 2).

Box 2. Capabilities of mechanistic computational models.

New Drug Design

Integrate data from diverse sources

Identify key, highly sensitive nodes in a signaling network

Inform optimal properties of new drugs (e.g. binding affinity)

Drug Discrimination

Predict effective vs. ineffective therapeutic strategies based on mechanism & properties that emerge in humans but not in experimental systems

Predict off-target drug effects that may lead to toxicity or drug failure

Predict optimal dosing, scheduling, route of administration, & drug combinations

Design experiments to better discriminate between drug candidates or existing & repurposed drugs

Translation to Diverse Human Population

Develop better understanding of human disease states

Translate results from experimental & animal systems into a human patient-and disease-specific context

Improve extrapolation between similar drugs, between experimental systems, and between patients, due to predictive, mechanism-based framework

Identify biomarkers for subpopulation inclusion or exclusion from clinical trials, e.g. based on patient-specific gene expression

Link measurable blood biomarkers to disease state at drug site-of-action

Establish Requirements for Success of Emerging Therapeutic Approaches

Gene Therapy (e.g. transfection efficiency)

Cell Therapy (e.g. cell type & delivery method)

Organ Transplant (e.g. drug regimens, predictive markers of rejection)

Engineered Tissue Constructs (e.g. requirements for functional vascularization)

Case Study 1: Drug Discrimination for Cardiac Arrhythmia

A promising application for mechanistic computational models is to perform virtual drug screening, eliminating candidate drugs that appear to work in single-cell systems, but have emergent properties in the context of human physiology that may result in adverse effects. The multi-scale mechanistic computational models built by Colleen Clancy and collaborators to compare anti-arrhythmia drugs, both in the context of a single cell and within tissues, provide an elegant example. Cardiac arrhythmia is a complex condition involving the (dis)coordinated electrical excitation of a large number of cells in the heart, which can cause sudden death. Based on single-cell experiments, blocking Na+ channels in cardiac myocytes was identified as a promising therapeutic strategy. However, clinical trials have demonstrated that, instead of suppressing arrhythmia, some of these drugs actually increase the incidence of sudden cardiac death by 2–3 fold in patients with a history of myocardial infarction [25]. Specifically, the class 1B anti-arrhythmia drug lidocaine, which has fast association-dissociation kinetics, has no known safety issues, but the class 1C anti-arrhythmia drug flecainide, with slow drug-channel association & dissociation, is known to cause conduction block at high physiological doses. As the pharmacokinetics of these drugs are well-characterized [26, 27], this study focused specifically on modeling drug pharmacodynamics within cardiac tissue.

The Clancy group model, which integrates decades of experimental study on the mechanisms of action of ion channels, represents the active and inactive states of the cardiac Na+ channel using a Markov model [28, 29]. To incorporate Na+-channel-blocking drugs, they used experimental data to estimate the affinity of both charged and neutral fractions of multiple drugs for each of the possible Na+ channel conformations [29]. The resulting model captured the ability of both drugs to slow conduction in single cardiac cells. To translate these observations to a clinically-relevant framework, the Clancy group and their collaborators simulated the actions of the same drugs in groups of coupled cells. The computational model — applied to both simulated 2D tissue sheets and 3D models of the human ventricle — was able to replicate the clinically-observed conduction block and increased sensitivity to early or late heart beats (which can lead to sudden cardiac death) after treatment with a high clinical dose of flecainide at fast pacing rates (160 bpm), but not with lidocaine [29]. This prediction, which emerged in organized tissues as a result of molecular-level differences in drug properties, was then validated in an animal model. In addition to discriminating between effective and ineffective drugs, this model allows for identification of safe dosing ranges and physiological counter-indications (tachycardia) for use. The Clancy group is now expanding this work to other drugs and personalized medicine applications [30, 31], including a study of sex-driven differences in susceptibility to arrhythmia as a result of sex-specific gene expression and sex hormones [32].

Case Study 2: Drug Target Identification for Cancer

Sensitivity analysis of mechanistic computational models allows for identification of key nodes in signaling pathways, which can be promising drug targets, as well as predicting changes in signaling resulting from the tuning of drug properties. This is of particular interest in fields where existing drugs have limited efficacy or are susceptible to resistance, as mechanistic models can also predict which patients will benefit from a particular drug. An excellent application of mechanistic computational models for cancer drug development is the work of Birgit Schoeberl and colleagues at Merrimack Pharmaceuticals. This group built detailed models of ligand-binding, receptor dimerization, and downstream signaling in the ErbB family, the receptors of which are commonly overexpressed or constitutively active in cancer [33, 34]. To build these models, they performed extensive screening of ErbB family receptor phosphorylation and Akt activation in diverse cancer cell lines. They then fit kinetic parameters in the model using this experimental data. They found that Akt signaling resulting from treatment with betacellulin or heregulin1-β was more sensitive to perturbation of ErbB3/HER3, a kinase-dead receptor tyrosine kinase, than the more commonly targeted ErbB1/EGFR or ErbB2/HER2 [34]. Without such modeling efforts, ErbB3 was unlikely to be identified as a promising drug target, due to its lack of an active kinase domain.

As a result of this work, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals designed an antibody (MM-121) specifically to inhibit phosphorylation of ErbB3, with an affinity for ErbB3 informed by the mechanistic computational modeling effort [34, 35]. In addition to drug design, the team was able to identify potential molecular biomarkers for response to MM-121. This has had a direct impact on the development process: high heregulin expression, predicted to be indicative of a positive response to MM-121 treatment, is an inclusion criteria for a current phase II clinical trial for MM-121 in combination with chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer [36]. Similar work has led to additional candidate antibodies currently in development. This example demonstrates the value of detailed computational models in not only discriminating between previously-developed and characterized drugs, but also in optimizing the targets and properties of future drugs.

Case Study 3: Better Therapeutic Approaches for Ischemic Disease

Mechanistic computational models are valuable both for screening potential drug targets in stand-alone pharmacodynamic models, and in the context of systems pharmacology-style PK/PD models, where diverse therapeutic delivery routes can be compared. We apply these strategies to study angiogenesis, the growth of new blood vessels from the existing vasculature. A promising approach to treat ischemic disease is to promote angiogenesis by targeting one of its key regulators, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). However, despite multiple clinical trials, no VEGF-based pro-angiogenic therapies have yet been approved [10, 37, 38], and success in promoting vascularization of engineered tissue constructs has also been limited [39]. This suggests that our current understanding of the underlying processes is insufficient to effectively promote vascular growth or remodeling.

To address this barrier, we build detailed mechanistic computational models of VEGF binding to its receptors, coreceptors, and the extracellular matrix (ECM), as well as the dimerization, intracellular trafficking and phosphorylation of the primary signaling VEGF receptor, VEGFR2. Such models can be used to study how changes in VEGF presentation (i.e. in solution or bound to the ECM) and the distribution of splice isoforms (which changes in disease), can alter endothelial cell signaling and the resulting vascular morphology [22]. As such, regulation of these properties is important to ensure proper perfusion and to control the permeability of developing vessels [40]. In addition to increasing our understanding of the pharmacodynamics of VEGF action in tissues, these biophysically-detailed models allow for comparison of many potential therapies, such as antibodies that target VEGF or block coreceptor binding, or gene therapy approaches [41–43]. We build these models upon detailed measurements of VEGF-induced signaling in cultured endothelial cells following various perturbations. However, the conditions for cell culture experiments are quite different than those in the human body (Fig. 1).

One of the strategies we use to translate this mechanistic insight into the context of the human body is by seeding these detailed endothelial cell signaling reactions (PD) into a PK model to form a mechanistically-detailed systems pharmacology model [23]. Our PK framework includes blood, healthy tissue, and diseased tissue (e.g. mouse or human calf muscle with peripheral artery disease), parameterized using histological and physiological data. These models allow us to predict how VEGF-mediated signaling changes in diseased tissue (compared to healthy tissue), which is very difficult to measure in patients. Additionally, we can predict how therapeutically-relevant quantities, such as the phosphorylation of VEGFR2, relate to measurable biomarkers, for example plasma levels of different VEGF isoforms [44], as we have previously done in cancer [43]. These whole-body models allow for screening of different delivery methods for therapies, such as intravenous or intramuscular antibody delivery, as well as gene, protein, or cell-based therapies and exercise [45]. While it is expected that these different therapy delivery methods (e.g. protein versus gene therapy) will result in different magnitudes & durations of effect in the target tissue, it is unclear without simulation which approaches may be most or least effective. Additionally, by incorporating mouse- and human-specific geometry and molecular (e.g. gene expression) changes, we can predict differences in therapy effectiveness between animal and human models [6]. This powerful framework provides great promise both to understand why previous therapeutic strategies have failed, and to identify promising future drug targets and delivery strategies.

Mechanistic computational models: a way forward for drug development

The body’s response to a drug is often an emergent property of the complex system. As such, drug design is not simply a problem of maximizing binding of a single drug to a single target. The case studies presented here demonstrate the unique ability of computational models including receptor- or channel-level mechanistic detail to improve selection of the right drug targets, properties, dosing & delivery route, and patient populations. The most effective way to implement mechanistic computational models of drug pharmacodynamics depends on the disease application. By linking predictions of important but difficult-to-measure markers of disease state to measureable plasma biomarkers, mechanistic models coupled to PK/PD frameworks (parameterized for specific disease applications) can give clinicians and drug designers a window into disease-driven changes on a patient-specific basis (Box 2). In other cases, where spatial patterning and cell-cell communication are known to play an important role, 3D tissue-scale computational models have a critical ability to capture emergent behaviors in healthy and diseased tissues. To incorporate pharmacokinetics into these 3D models, PK/PD model predictions can provide the local drug concentration (due to delivery and average consumption by the target tissue) and help parameterize the 3D pharmacodynamic model. Regardless of approach, the mechanistic detail is what makes these models predictive, conferring the ability to identify critical drug design requirements and patient counter-indications.

As highlighted by the diverse applications in the case studies, mechanistic computational models can be applied to any disease state, be it acute or chronic, and regardless of whether the disease stems from infection, genetic factors, and/or environmental or behavior factors. The only requirement is sufficient experimental information to build a mechanistic model of the underlying molecular changes. Computational models can also be used to test the feasibility of promising, but not yet widely successful, therapeutic strategies (Box 2). For example, models can predict the transfection efficiency required for gene and cell therapy to be effective across a heterogeneous patient population [46, 47]. In addition to drug design, mechanistic computational models, paired with traditional drug development tools, can be used to identify better biomarkers for disease progression and therapy response [48], better predict differences in response in animal models and human patients [49, 50], and to perform failure analysis on ineffective drugs [3, 29], informing the next generation of therapeutics. Personalized medicine approaches can also benefit from the use of mechanistic models, for example in predicting dosing regimes and drug combinations based on the molecular markers of individual patients or disease subtypes [12, 14]. Because mechanistic computational models can address some of the key shortcomings of the drug development process, they hold promise, used hand-in-hand with experimental approaches, to reduce clinical trial failure, reduce the average per-drug time and cost investment for development, and ultimately, improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Department of Defense (DoD) National Defense Science & Engineering Graduate Fellowship (NDSEG) to LEC. This work was also funded in part by NIH R01HL101200, NIH R00HL093219, and a Sloan Research Fellowship to FMG.

Abbreviations

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- PAD

peripheral arterial disease

- PD

pharmacodynamics

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pammolli F, Magazzini L, Riccaboni M. The productivity crisis in pharmaceutical R&D. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2011;10(6):428–38. doi: 10.1038/nrd3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scannell JW, Blanckley A, Boldon H, Warrington B. Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2012;11(3):191–200. doi: 10.1038/nrd3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul SM, Mytelka DS, Dunwiddie CT, Persinger CC, Munos BH, Lindborg SR, et al. How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry’s grand challenge. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2010;9(3):203–14. doi: 10.1038/nrd3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leil TA, Bertz R. Quantitative Systems Pharmacology can reduce attrition and improve productivity in pharmaceutical research and development. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorger PK, Allerheiligen SRB, Abernethy DR, Altman RB, Brouwer KLR, Califano A, et al. Quantitative and Systems Pharmacology in the Post-genomic Era: New Approaches to Discovering Drugs and Understanding Therapeutic Mechanisms. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agoram BM, Martin SW, van der Graaf PH. The role of mechanism-based pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) modelling in translational research of biologics. Drug Discovery Today. 2007;12(23–24):1018–24. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gobburu JVS, Lesko LJ. Quantitative Disease, Drug, and Trial Models. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2009;49:291–301. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Graaf PH, Gabrielsson J. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic reasoning in drug discovery and early development. Future Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;1(8):1371–4. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swinney DC, Anthony J. How were new medicines discovered? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2011;10(7):507–19. doi: 10.1038/nrd3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clegg LE, Mac Gabhann F. Systems biology of the microvasculature. Integrative Biology. 2015 doi: 10.1039/C4IB00296B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Graaf PH, Benson N. Systems Pharmacology: Bridging Systems Biology and Pharmacokinetics-Pharmacodynamics (PKPD) in Drug Discovery and Development. Pharmaceutical Research. 2011;28(7):1460–4. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyengar R, Zhao S, Chung S-W, Mager DE, Gallo JM. Merging Systems Biology with Pharmacodynamics. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(126) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleiman LB, Maiwald T, Conzelmann H, Lauffenburger DA, Sorger PK. Rapid Phospho-Turnover by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases Impacts Downstream Signaling and Drug Binding. Molecular Cell. 2011;43(5):723–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang XY, Birtwistle MR, Gallo JM. A General Network Pharmacodynamic Model-Based Design Pipeline for Customized Cancer Therapy Applied to the VEGFR Pathway. CPT: pharmacometrics & systems pharmacology. 2014;3:e92–e. doi: 10.1038/psp.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindner AU, Concannon CG, Boukes GJ, Cannon MD, Llambi F, Ryan D, et al. Systems Analysis of BCL2 Protein Family Interactions Establishes a Model to Predict Responses to Chemotherapy. Cancer Research. 2013;73(2):519–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-12-2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ploeger BA, van der Graaf PH, Danhof M. Incorporating Receptor Theory in Mechanism-Based Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) Modeling. Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 2009;24(1):3–15. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.24.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holford NHG, Sheiner LB. Understanding the dose-effect relationship- clinical application of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic models. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 1981;6(6):429–53. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198106060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niepel M, Hafner M, Pace EA, Chung M, Chai DH, Zhou L, et al. Profiles of Basal and Stimulated Receptor Signaling Networks Predict Drug Response in Breast Cancer Lines. Science Signaling. 2013;6(294) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niepel M, Hafner M, Pace EA, Chung M, Chai DH, Zhou L, et al. Analysis of growth factor signaling in genetically diverse breast cancer lines. Bmc Biology. 2014;12 doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bagci-Onder T, Agarwal A, Flusberg D, Wanningen S, Sorger P, Shah K. Real-time imaging of the dynamics of death receptors and therapeutics that overcome TRAIL resistance in tumors. Oncogene. 2013;32(23):2818–27. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallo JM, Birtwistle MR. Network pharmacodynamic models for customized cancer therapy. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine. 2015:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clegg L, Mac Gabhann F. Site-specific phosphorylation of VEGFR2 is mediated by receptor trafficking: insights from a computational model. PLoS Computational Biology. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004158. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stefanini MO, Wu FT, Mac Gabhann F, Popel AS. A compartment model of VEGF distribution in blood, healthy and diseased tissues. BMC Systems Biology. 2008;2 doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-2-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballesta A, Zhou Q, Zhang X, Lv H, Gallo JM. Multiscale design of cell-type-specific pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic models for personalized medicine: application to temozolomide in brain tumors. CPT: pharmacometrics & systems pharmacology. 2014;3:e112–e. doi: 10.1038/psp.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preliminary Report: Effect of Encainide and Flecainide on Mortality in a Randomized Trial of Arrhythmia Suppression after Myocardial Infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;321(6):406–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908103210629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perry JC, McQuinn RL, Smith RT, Gothing C, Fredell P, Garson A. Flecainide acetate for resistant arrhythmias in the young- efficacy and pharmacokientics. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1989;14(1):185–91. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nolan PE. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous agents for ventricular arrhythmias. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17(2):S65–S75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clancy CE, Rudy Y. Linking a genetic defect to its cellular phenotype in a cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1999;400(6744):566–9. doi: 10.1038/23034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno JD, Zhu ZI, Yang P-C, Bankston JR, Jeng M-T, Kang C, et al. A Computational Model to Predict the Effects of Class I Anti-Arrhythmic Drugs on Ventricular Rhythms. Science Translational Medicine. 2011;3(98) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romero L, Trenor B, Yang P-C, Saiz J, Clancy CE. In silico screening of the impact of hERG channel kinetic abnormalities on channel block and susceptibility to acquired long QT syndrome. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2014;72:126–37. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreno JD, Yang P-C, Bankston JR, Grandi E, Bers DM, Kass RS, et al. Ranolazine for Congenital and Acquired Late I-Na -Linked Arrhythmias In Silico Pharmacological Screening. Circulation Research. 2013;113(7):E50–E61. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.113.301971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang P-C, Clancy CE. In silico prediction of sex-based differences in human susceptibility to cardiac ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Frontiers in Physiology. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen WW, Schoeberl B, Jasper PJ, Niepel M, Nielsen UB, Lauffenburger DA, et al. Input-output behavior of ErbB signaling pathways as revealed by a mass action model trained against dynamic data. Molecular Systems Biology. 2009;5 doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoeberl B, Pace EA, Fitzgerald JB, Harms BD, Xu L, Nie L, et al. Therapeutically Targeting ErbB3: A Key Node in Ligand-Induced Activation of the ErbB Receptor-PI3K Axis. Science Signaling. 2009;2(77) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoeberl B, Faber AC, Li D, Liang M-C, Crosby K, Onsum M, et al. An ErbB3 Antibody, MM-121, Is Active in Cancers with Ligand-Dependent Activation. Cancer Research. 2010;70(6):2485–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-09-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merrimack Pharmaceuticals. A Study of MM-121 in Combination With Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy Alone in Heregulin Positive NSCLC ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] National Library of Medicine; US: [cited 2015 05/20]. Available from: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02387216?term=MM-121&rank=7. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mac Gabhann F, Qutub AA, Annex BH, Popel AS. Systems biology of pro-angiogenic therapies targeting the VEGF system. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Systems Biology and Medicine. 2010;2(6):694–707. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grochot-Przeczek A, Dulak J, Jozkowicz A. Therapeutic angiogenesis for revascularization in peripheral artery disease. Gene. 2013;525(2):220–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.03.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briquez PS, Hubbell JA, Martino MM. Extracellular Matrix-Inspired Growth Factor Delivery Systems for Skin Wound Healing. Advances in Wound Care. 2015 doi: 10.1089/wound.2014.0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vempati P, Popel AS, Mac Gabhann F. Extracellular regulation of VEGF: Isoforms, proteolysis, and vascular patterning. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2014;25(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.11.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mac Gabhann F, Popel AS. Targeting neuropilin-1 to inhibit VEGF signaling in cancer: comparison of therapeutic approaches. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2(12):e180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mac Gabhann F, Ji JW, Popel AS. Multi-scale computational models of pro-angiogenic treatments in peripheral arterial disease. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35(6):982–94. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9303-0. Epub 2007/04/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stefanini MO, Wu FTH, Mac Gabhann F, Popel AS. Increase of Plasma VEGF after Intravenous Administration of Bevacizumab Is Predicted by a Pharmacokinetic Model. Cancer Research. 2010;70(23):9886–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-10-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clegg L, Mac Gabhann F. Regulation of VEGFR2 Activation in Skeletal Muscle by VEGF Isoforms with Differential ECM- and NRP1-Binding: a Computational Study. The FASEB Journal. 2015;29(1 Supplement) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu FTH, Stefanini MO, Gabhann FM, Popel AS. A Compartment Model of VEGF Distribution in Humans in the Presence of Soluble VEGF Receptor-1 Acting as a Ligand Trap. Plos One. 2009;4(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hosseini I, Mac Gabhann F. APOBEC3G-Augmented Stem Cell Therapy to Modulate HIV Replication: A Computational Study. Plos One. 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hosseini I, Mac Gabhann F. Designing Stem-Cell Based Anti-HIV Therapies using Molecular-Detailed Multiscale Models. Biophysical Journal. 108(2):314a. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.1707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bender RJ, Mac Gabhann F. Personalized medicine of VEGF-targeting therapies: a multiscale modeling approach for developing predictive biomarkers from gene expression data. 2015 Interagency Modeling and Analysis Group MSM Consortium Meeting NIH; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mager DE, Woo S, Jusko WJ. Scaling Pharmacodynamics from In Vitro and Preclinical Animal Studies to Humans. Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 2009;24(1):16–24. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.24.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Finley SD, Dhar M, Popel AS. Compartment model predicts VEGF secretion and investigates the effects of VEGF trap in tumor-bearing mice. Frontiers in oncology. 2013;3:196. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]