Abstract

Background

Microvascular dysregulation, abnormal rheology, and vaso-occlusive events play a role in the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease (SCD). We hypothesized that abnormalities in skeletal muscle perfusion in a murine model of SCD could be parametrically assessed by quantitative contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEU) perfusion imaging.

Methods

We studied a murine model of moderate SCD without anemia produced by homozygous β-globin deletion replaced by human βs-globin transgene (NY1DD−/−, n=18), heterozygous transgene replacement (NY1DD+/−, n=19), and C57Bl/6 control mice (n=14). Quantitative CEU of the proximal hindlimb skeletal muscle was performed at rest and during contractile exercise (2 Hz). Time-intensity data were analyzed to measure microvascular blood volume (MBV), microvascular blood transit rate (β), and microvascular blood flow (MBF). Erythrocyte deformability was measured by elongation at various rotational shears.

Results

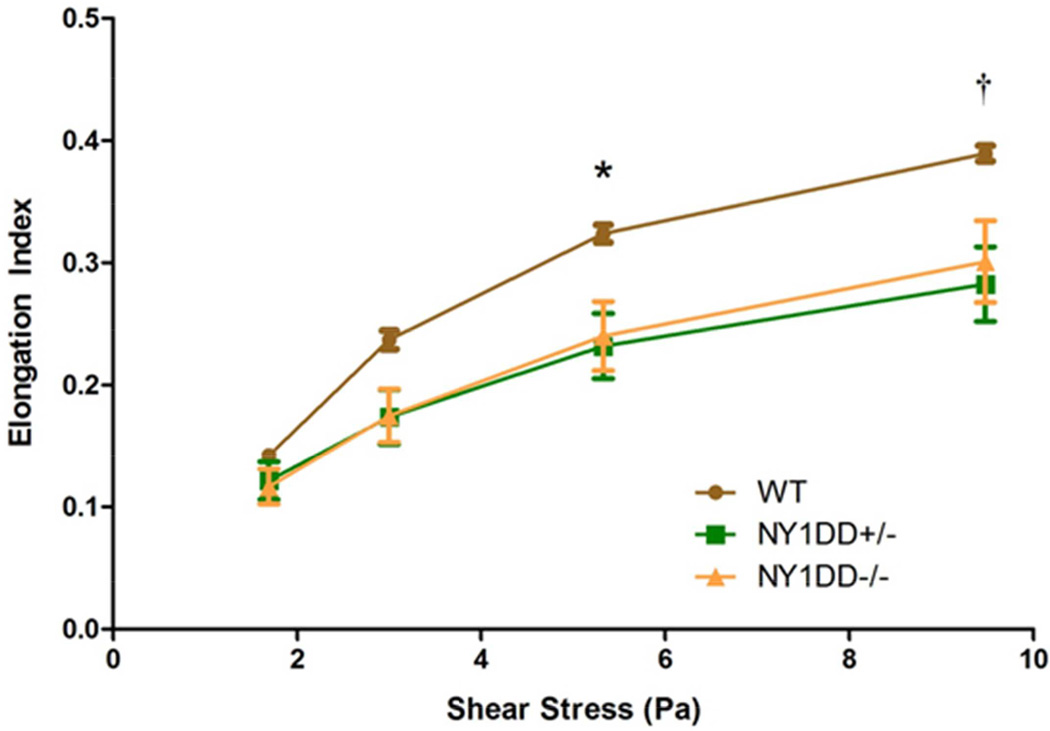

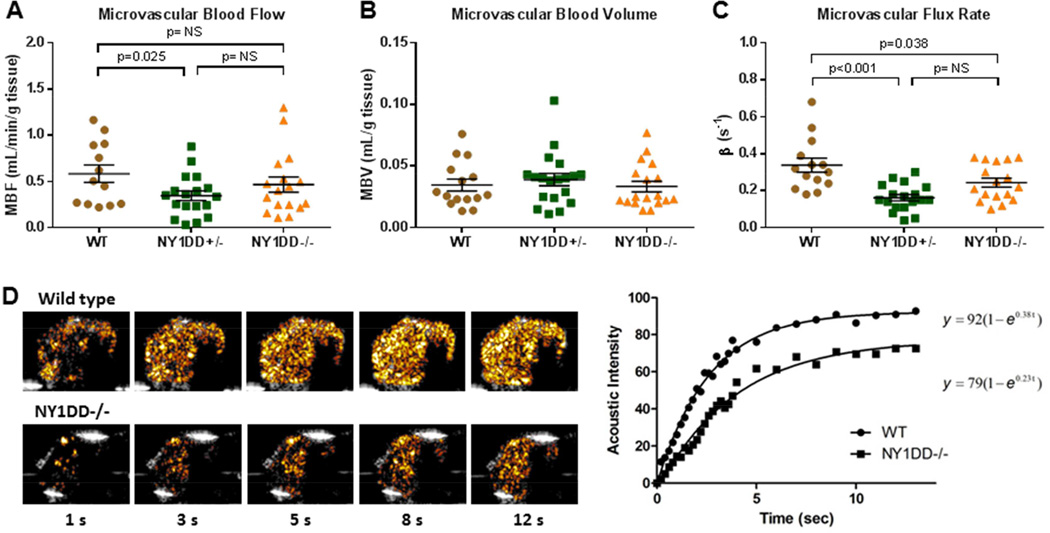

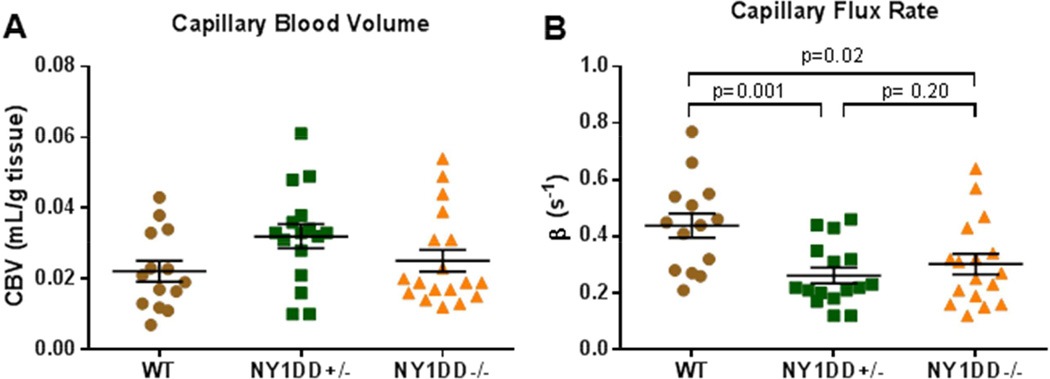

At rest, muscle MBV was similar between strains whereas β was significantly (ANOVA p=0.0015) reduced to a similar degree in NY1DD−/− and NY1DD+/− compared to wild-type mice (0.24±0.10, 0.16±0.07, and 0.34±0.14 s−1, respectively), resulting in a reduction in MBF. During contractile exercise, there were no group-wise differences in β (1.43±0.67 s−1, 1.09±0.42 s−1, 1.36±0.49 s−1; for NY1DD−/−, NY1DD+/−, and wild-type, respectively), nor for MBF or MBV. Erythrocyte deformability at high shear stress (≥5 Pa) was mildly reduced in both transgenic groups, although it did not correlate with the blood flow or β.

Conclusions

CEU in skeletal muscle has revealed a lower microvascular blood transit rate in the NY1DD model of SCD and sickle trait but no alterations in MBV. The abnormality in microvascular blood transit rate is likely due to vasomotor dysfunction since it abrogated by contractile exercise and at rest is only weakly related to erythrocyte deformability.

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is a multi-system disorder caused by a single nucleotide mutation at the sixth position of the red blood cell (RBC) β-globin gene that substitutes valine for glutamic acid.1,2 The pathophysiology of SCD is complex and involves much more than simply the hemolytic anemia produced by hemoglobin polymerization. Dysregulation of microvascular perfusion is thought to play a key role in the myriad of SCD complications such as acute pain crisis, pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, priapism, and cognitive impairment.1–3 Abnormal rheology of sickled erythrocytes contributes to vascular-related complications. However, other mechanisms have been implicated including vaso-occlusive microthrombosis.4 Abnormal vasomotor tone also occurs as a result of free hemoglobin which scavenges nitric oxide (NO), release of vasoconstrictors from platelet activation, and oxidative stress which can inactivate NO and promote smooth muscle constriction.5–8

Non-invasive techniques that are capable of comprehensively assessing the status of the microcirculation are likely to yield additional insight into the vascular pathophysiology of SCD, and could be used for pre-clinical and clinical testing of new therapies. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEU) has been used extensively in humans and animal models to evaluate microvascular responses in various disease processes. A distinct advantage of CEU microvascular perfusion imaging in SCD is that it provides quantitative parametric information on both erythrocyte microvascular transit rate which is influenced by blood rheology and resistance arteriolar tone, and (2) microvascular blood volume (MBV) which may become abnormal by vaso-occlusion or increased pre-capillary terminal arteriolar tone.9–12 In this study, we hypothesized that quantitative CEU perfusion imaging could detect skeletal muscle perfusion abnormalities and characterize abnormalities in RBC microvascular transit rate and MBV in a genetically-modified murine model of moderate SCD under healthy non-crisis conditions.

METHODS

Murine Model and Surgical Preparation

Studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Oregon Health & Science University. As a model for SCD, NY1DD−/− mice (Jackson Laboratories) were studied. These mice have a C57/BL6 background, are homozygous for a spontaneous deletion at the β-major-globin locus (βMDD), and carry a human α- and βS-globin transgenes (αHβS[βMDD]).13 Mice that are heterozygous for the β-major-globin deletion (NY1DD+/−) were used as a model for sickle trait and C57/BL6 mice were used as wild-type controls. Mice were studied at 8–14 weeks of age (NY1DD−/− n=18, NY1DD+/− n=19, wild-type n=10). Animals were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane (1.0–1.2%) mixed with room air and were kept euthermic with a heating pad. A jugular vein was cannulated for administration of microbubble contrast agents. All studies in SCD mice were performed on animals that were in apparent good health without any behavioral evidence of pain or distress.

Microbubble Preparation

Lipid-shelled microbubbles were prepared by sonication of a decafluorobutane gas-saturated aqueous suspension of 2 mg/mL distearoylphosphatidylcholine and 1 mg/mL polyoxyethylene-40-stearate. Microbubble size distribution and concentration was measured by electrozone sensing (Multisizer III, Beckman Coulter).

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound Perfusion Imaging

Contrast ultrasound perfusion imaging was performed using a linear-array transducer at a centerline frequency of 7 MHz (Sequoia 512, Siemens Medical Systems). The nonlinear fundamental signal component for microbubbles was detected using multi-pulse phase- and amplitude-modulation at a mechanical index of 0.18 and a dynamic range of 55 db. Gain settings were optimized and held constant. Blood pool signal (IB) was measured from a region of interest placed in the left ventricular cavity at end-diastole during a microbubble intravenous infusion rate of 5×105 min−1. The infusion rate was then increased to 1×107 min−1 and the proximal hindlimb adductor muscles were imaged in a transverse plane halfway between the inguinal fold and the knee. Images were acquired at a frame rate of 20 Hz after a brief high-power (mechanical index 1.0–1.1) destructive pulse sequence. Background-subtracted video intensity was calculated by digital subtraction of the first frame acquired immediately after the high-power sequence. Time-intensity data were fit to the function:

where y is intensity at time t, A is the plateau intensity, and the rate constant β represents the microvascular flux rate.9,10 Skeletal muscle MBV was quantified by:

where 1.06 is tissue density (g/cm3), F is the scaling factor for the 20-fold lower microbubble infusion rate for measuring IB, which was used to avoid dynamic range saturation, and 1.1 is a coefficient to correct for murine sternal attenuation measured a priori from in vitro experiments. Blood flow (ml/min/g) was calculated as the product of MBV and β.9 Skeletal muscle perfusion imaging was performed both at rest and during contractile exercise produced by electrostimulation of the proximal hindlimb adductor muscle at 1 Hz (5 mA).

Capillary Blood Volume and Flux Rate

Skeletal muscle CEU perfusion imaging data were re-analyzed in order to parse capillary MBV and flux rate from that in the total microvascular compartment (capillaries and non-capillary microvessels). Time-intensity data were refit to the mathematical functions described above after recalculating background-subtracted intensity using the frame obtained 1 second after the destructive pulse sequence as background. As previously described,10,14 based on our hydrophone measurements of beam elevational dimension (1.2 mm) this image reprocessing eliminates data from all vessels with an average microvascular blood velocity of approximately 1.0–1.5 mm/s, thereby eliminating arteriolar and venular data in skeletal muscle.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography (Vevo-770, Visualsonics Inc., Toronto, Canada) was performed prior to CEU perfusion imaging in approximately two-thirds of animals for each mouse strain. Imaging was performed in the parasternal long-axis and mid-ventricular short-axis planes at 40 MHz. Two-dimensional measurements were made using ECG-gated sequential M-mode acquisitions for an effective 2-D frame rate of approximately 1,000 Hz. Left ventricular internal diameter at end-diastole (LVIDd) and end-systole (LVIDs) in the minor axis were measured, and fractional shortening was calculated by (LVIDd-LVIDs)/ LVIDd. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated based on single plane 2-D measurements.15 Septal and posterior wall thickness were measured at end-systole and end-diastole, and were used to calculate thickening fraction which was averaged for the two walls. Stroke volume (SV) was measured by the product of the LV outflow tract area and angle-corrected time-velocity integral measured by pulsed-wave Doppler (θ<20°). Cardiac output was calculated by the product of SV and electrocardiographically-measured heart rate. Measurements from three consecutive cardiac cycles were averaged for all echocardiographic parameters.

Complete Blood Count

Complete blood count (CBC) and blood smears stained with Wright’s stain were performed in mice separate from those undergoing non-invasive imaging (NY1DD−/− and C57Bl/6 controls, n=2 each) in order to avoid significant blood loss or the stimulation of even mild crisis which could influence CEU perfusion imaging and echocardiographic data. Blood smears were also performed in an additional 4 mice NY1DD−/− and control mice 30 min after aerosolized lipopolysaccharide (100 µg/mL) in order to confirm inducible hemoglobin polmerization.

Erythrocyte Deformability

Erythrocyte deformability at variable shear was evaluated using laser-assisted optical rotational cell analysis (LORRCA, Mechatronics).16 Twenty-five microliters of whole blood in EDTA was mixed with 5 mL of polyvinyl propylene (50 mg/mL). Deformability by LORRCA was assessed at shear stresses from 1.7 to 9.5 Pa and expressed as an elongation index (EI) which was calculated from the ratio of the axial and transverse erythrocyte diameters relative to the direction of shear.

Histology

Immersion-fixed paraffin-embedded skeletal muscle was sectioned and stained with Masson’s trichrome to evaluate the spatial extent of fibrosis. The degree of fibrosis other than in the perivascular regions was qualitatively scored by an observer blinded to animal identity according to the degree of fibrosis: normal perimysial and endomysial collagen patterns; mild expansion of the perimysium and/or endomysium; moderate to severe expansion of the perimysium and/or endomysium; or large territories of replacement fibrosis.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism (version 5.0, GraphPad Software). Group-wise differences were assessed by Mann-Whitney U test for data that were determined to be non-normally distributed by D'Agostino and Pearson omnibus test. For data with normal distribution, group-wise differences were assessed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Student’s t-test and Bonferroni’s correction. Grubb’s test was used to confirm the presence of single outlier data when appropriate. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05 (2-sided).

RESULTS

Heart Rate and Echocardiographic Data

There were no significant differences between the mouse strains with regards to heart rate, LV dimensions, or any of the indices of systolic function including LVEF, thickening fraction, fractional shortening, stroke volume and cardiac output (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Heart Rate and Echocardiographic Data

| Wild-type (n=6) | NY1DD−/− (n=11) | NY1DD+/− (n=8) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate (min−1) | 442±46 | 427±45 | 454±43 |

| Thickening fraction (%) | 43.5±3.5 | 41.4±11.9 | 39.4±9.3 |

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.41±0.28 | 3.48±0.48 | 3.35±0.29 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.85±0.15 | 2.07±0.52 | 2.06±0.43 |

| Fractional shortening | 0.44±0.03 | 0.39±0.09 | 0.42±0.12 |

| LVEF (%) | 75.7±3.5 | 71.4±12.7 | 70.0±11.3 |

| Stroke Volume (µL) | 52±21 | 50±14 | 63±20 |

| Cardiac output (mL/min) | 23±12 | 21±5 | 29±11 |

LVIDd, left ventricular end-diastolic internal dimension; LVIDs, left ventricular end-systolic internal dimension.

CBC and Erythrocyte Deformability

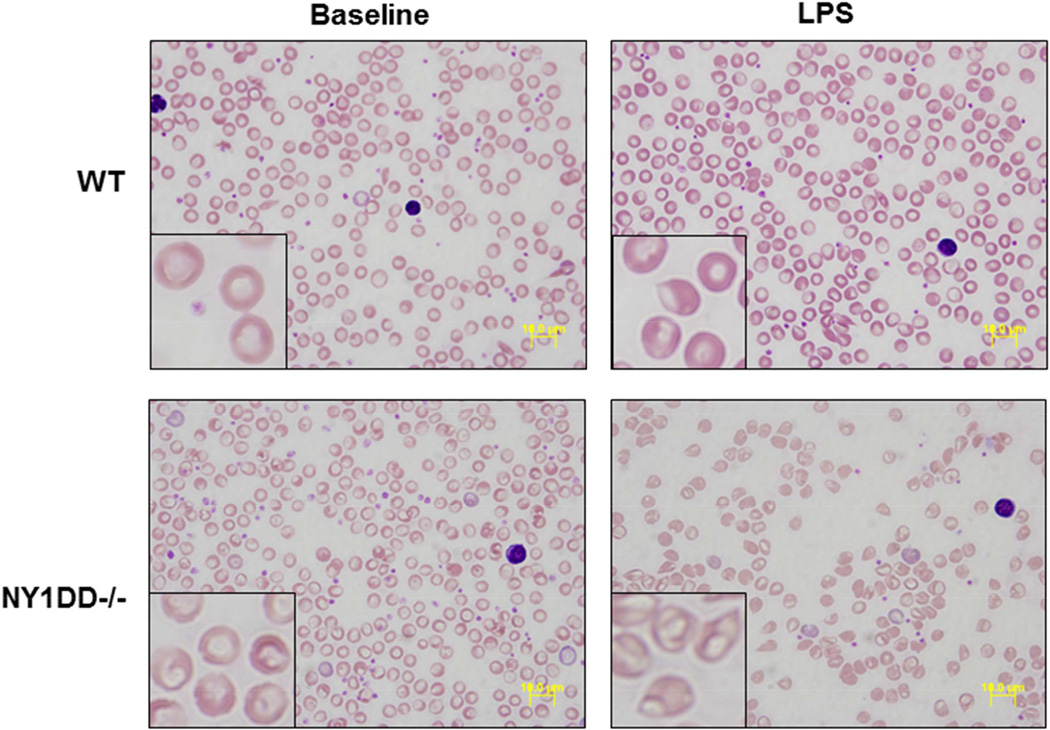

On CBC, there were no relevant differences between C57Bl/6 control and NY1DD−/− mice (Table 2). As noted in previous studies,13 there was no evidence for anemia or increased mean corpuscular volume (MCV) in the NY1DD−/− mice. On microscopy, under basal conditions NY1DD−/− erythrocyte appearance was normal, whereas erythrocyte shape deformation was apparent in NY1DD−/− mice treated with LPS, thereby confirming the expected phenotype of hemoglobin polymerization with stress (Figure 1). Under basal conditions, erythrocyte deformability measured by elongation index was similar at the lower end of the shear stresses tested (Figure 2). At the higher end of shear stresses, deformability tended to be lower for both NY1DD−/− and NY1DD+/− mice compared to controls. There was no significant correlation between the elongation index and resting blood flow or β.

TABLE 2.

Complete Blood Count Data from Wild-type and NY1DD−/− Mice.

| Wild-type (n=2) | NY1DD−/− (n=2) | |

|---|---|---|

| WBC (103/µL) | 7.2±2.9 | 10.1±3.2 |

| RBC (106/µL) | 9.5±0.3 | 11.3±0.5 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 41.8±1.4 | 44.1±0.2 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.5±0.3 | 12.9±0.4 |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume (fL) | 46.7±0.3 | 49±1.4 |

RBC, red blood cell count; WBC, white blood cell count.

Figure 1.

Examples of blood smears from wild-type (WT) and NY1DD−/− mice under low and high (inset) magnification. Abnormalities in erythrocyte morphology can be appreciated only in mice treated with LPS.

Figure 2.

Erythrocyte deformability illustrated by the mean (±SEM) elongation index at various rotational shear stresses. *p=0.04 for NY1DD−/− and p=0.01 for NY1DD+/− versus wild-type; †p=0.068 for NY1DD−/− and p=0.008 for NY1DD+/− versus wild-type.

Skeletal Muscle Microvascular Perfusion

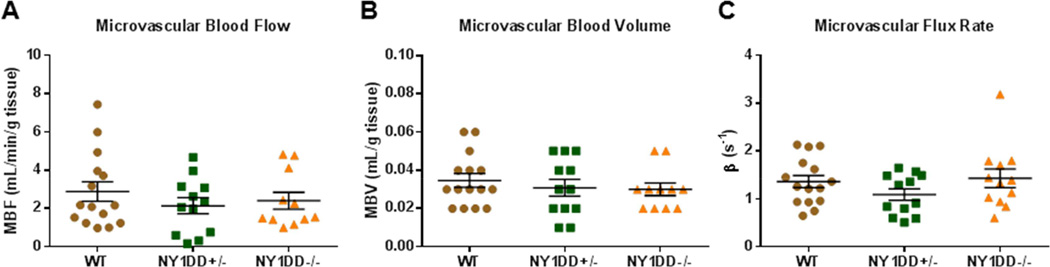

Contrast ultrasound perfusion was well tolerated in all animals and there was no evidence for behavioral markers for pain or distress in any of the NY1DD mice at the time that perfusion imaging was performed. Total microvascular blood flow was slightly lower in both NY1DD−/− and NY1DD+/− mice compared to control mice but differences were statistically significant only for the NY1DD+/− (Figure 3A). Parametric assessment of muscle microvascular perfusion indicated that MBV was nearly identical between groups (Figure 3B). In the calculation of MBV, blood pool signal was also similar between groups (94±29, 90±34, and 102±21 VIU in NY1DD−/−, NY1DD+/−, and wild-type controls, respectively; ANOVA p=0.49). Microvascular flux rate (β-value) was significantly lower in both NY1DD groups compared to wild type controls (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Resting skeletal muscle CEU perfusion imaging data demonstrating group-wise differences in (A) microvascular blood flow, (B) microvascular blood volume, and (C) microvascular transit rate or β. Lines and error bars represent mean (±SEM). (D) Background-subtracted color-coded CEU images at different times after a destructive pulse sequence and corresponding time-intensity data from a wild-type and NY1DD−/− mouse illustrating differences in resting perfusion manifest as a reduction in the β-value or rate function. Grubb’s test identified a single outlier β-value for each of the NY1DD groups.

Parametric CEU data was reanalyzed in order to derive capillary MBV and flux rate. These values demonstrated similar trends as total microvascular perfusion with a reduction in flux rate (β-value) in both NY1DD−/− and NY1DD+/− mice, but no difference in capillary blood volume (Figure 4). The non-capillary microvascular blood volume, which was estimated by the difference between total MBV and capillary MBV did not differ between groups (ANOVA p=0.10).

Figure 4.

Parametric values of (A) capillary blood volume and (B) capillary blood transit rate after reanalyzing CEU perfusion imaging data to exclude most of the non-capillary microvascular compartment. ANOVA was non-significant for capillary blood volume (p=0.10) but was significant (p=0.004) for transit rate.

Skeletal muscle perfusion imaging was also performed during modest contractile exercise to determine whether perfusion abnormalities seen at rest were negated by a physiologic hyperemic stimulus (Figure 5). In control mice, microvascular blood flow increased during exercise by approximately 5-fold (mean 505±314 % increase from baseline, p<0.001). The increase in blood flow was attributable primarily to an increase in microvascular flux rate (mean 459±233% increase from baseline, p<0.001). During exercise, there were no group-wise differences in microvascular blood flow, microvascular flux rate or MBV. Because resting β was lower in the transgenic animals, the percent increase in microvascular flux rate was greater (p<0.05) for NY1DD−/− (785±475 %) and NY1DD+/− (750±371 %) mice compared to controls.

Figure 5.

Skeletal muscle CEU perfusion imaging data during contractile exercise (2 Hz) demonstrating (A) microvascular blood flow, (B) microvascular blood volume, and (C) microvascular transit rate or β. Lines and error bars represent mean (±SEM). No significant group-wise differences were found.

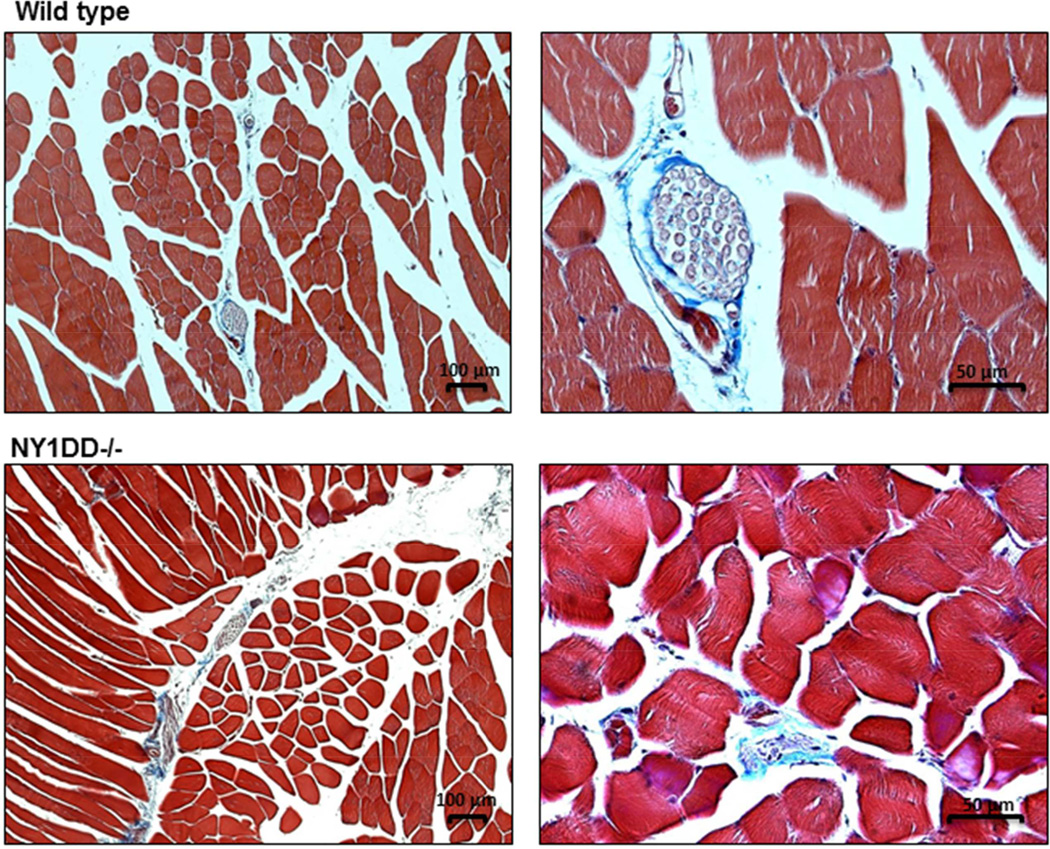

Histology

On histology with Masson’s trichrome (Figure 6), there tended to be slightly greater degree of matrix staining between myocytes and muscle fibers consistent with proliferation of the endomysium and perimysium. However, these differences were mild and inconsistent, and there was no evidence for large regions of replacement fibrosis that are indicative of cell loss from vaso-occlusive events. There was no evidence for ultrasound-mediated adverse bioeffects such as vascular hemorrhage.

Figure 6.

Illustration of histology with Masson’s trichrome staining at low and high magnification from a wild-type and NY1DD−/− mouse illustrating no major differences in the degree of fibrosis and no regions of replacement fibrosis in the NY1DD−/− model.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have applied CEU perfusion imaging in murine model of SCD to detect abnormalities in skeletal muscle perfusion under normoxic, steady-state conditions. Our data indicate that there are abnormalities in muscle perfusion in the NY1DD model of SCD which is manifest primarily by an abnormal microvascular blood flux rate at rest in both the NY1DD−/− and NY1DD+/− mice. These abnormalities, however, are entirely reversible during contractile exercise of the muscle indicating that abnormal flux rate in the SCD models most likely reflects functional abnormalities in vasodilator-vasoconstrictor tone at rest and not from abnormal hemorheology or fibrotic replacement.

Murine models of SCD have been developed and have been used to gain a better understanding of the pathophysiology of SCD and to test new candidate therapies.13,17,18 These models differ in their genetic modifications, which likely accounts for the substantial variation in phenotype with regards to disease severity and which tissues are involved. Accordingly, the results of our study must be viewed in the context of the NY1DD model that was selected because it is not accompanied by anemia that can be severe in other models. These mice have a somewhat milder disease manifestation compared to some other models. Although NY1DD mice can be easily provoked to crisis with stressors such as hypoxia, infection, or lipopolysaccharide; under basal conditions the amount of hemolysis is low, the degree of anemia is mild if present at all, and erythrocyte dysmorphism is not severe.19 Our data show that under basal conditions there was no significant hemolytic anemia, and there was only a mild abnormality in erythrocyte deformability without increase in mean corpuscular volume or obvious visual abnormality in erythrocyte morphology unless mice were challenged with LPS.

Despite the relatively subtle hematologic findings in NY1DD mice, CEU revealed lower resting skeletal microvascular flux rate (β) compared to wild-type mice. Echocardiographic data argued against any contribution from reduced cardiac function. The degree to which flux rate was reduced at rest was similar for NY1DD−/− mice and NY1DD+/− mice which carry the human beta-S-globin transgene but are heterozygous for deletion of native murine beta-globin. Together with the erythrocyte deformability results, these data suggest that perhaps there is little difference in the phenotype for NY1DD−/− and NY1DD+/− cohorts.

The potential explanations for isolated reduction in microvascular flux rate without change in MBV as a cause of reduced perfusion include: (1) increased resistance at the capillary level, or (2) increased tone at the level of the classic resistance arterioles which in turn reduces head pressure for the capillary network. In SCD, it would be reasonable to implicate abnormal erythrocyte rheology which can have dramatic effects on blood relative apparent viscosity and conductance at the capillary level where blood properties become non-Newtonian.20,21 There are several facts that argue against this explanation for reduced resting β. The NY1DD mice did not have any major abnormalities on CBC, and erythrocyte deformability was only mildly reduced and not directly related to the resting β on CEU. Perhaps more importantly, alterations in blood viscosity and erythrocyte deformability should produce flow abnormalities that become more pronounced with hyperemia. We found the opposite, that perfusion was no different between wild-type and NY1DD mice during exercise.

It is then quite likely that abnormalities in resting perfusion in the NY1DD mice were due to abnormal tone at the pre-capillary arteriolar level. There are many potential explanations for this. Reduced bioavailability of the endothelial-derived vasodilator NO occurs secondary to either increased oxidative stress or scavenging by free hemoglobin, both of which occur in SCD.5,7 This is an unlikely explanation for our findings since there was no evidence for significant hemolysis. Moreover, reduction in NO with Nω-nitro-L-methyl ester HCL (L-NAME) is manifest on CEU imaging more by a reduction in skeletal muscle MBV than β.22 The ability of exercise to reverse the resting abnormalities in perfusion suggest not a deficiency in vasodilator production but rather increased vasoconstrictor tone which can be overcome with the strong vasodilator stimulus. A myriad of studies performed in patients with SCD and in murine models have demonstrated an elevation in the plasma levels of many biologic vasoconstrictors including endothelin-1, angiotensin II, and catecholamines.23,24 The current study is the first to demonstrate abnormal resting perfusion in skeletal muscle in a murine model of SCD which is likely secondary to these abnormal vasomotor profiles.

There are several limitations of the study that deserve mention. The most important is that we have not directly tested the contribution of each potential vasoconstrictor or vasodilator in this study. This testing would require a major research effort and hundreds of animals undergoing pharmacologic inhibition of each pathway. We also studied mice at a fairly young age and cannot rule out the occurrence of other microvascular abnormalities or tissue fibrosis at a more advanced age. We also cannot extrapolate our results to other transgenic mouse models that have evidence for low-level hemolysis or to patients with SCD or sickle-trait. To address the latter issue, a clinical trial is currently underway using CEU to evaluate resting microvascular perfusion and how it changes during crisis conditions. We do not have any evidence that the reduction in tissue perfusion at rest in NY1DD mice results in tissue ischemia. In fact, the normalization of blood flow with exercise would argue the opposite. With regards to exercise blood flow, we cannot necessarily extrapolate electrostimulated muscle perfusion results to what would occur in conscious subjects undergoing exercise. In fact, results from humans undergoing contractile exercise differ slightly in that exercise produces augmentation in both β and MBV.25 Finally, the low number of blood counts in this study was a result of the loss of phenotype severity over time in this model not attributable to transgene number that has been noted by other investigators. We did not anticipate this loss of phenotype and had only performed CBC on a small number of mice before loss of phenotype.

In summary, quantitative CEU performed in a murine model of SCD has demonstrated impaired microvascular transit rate at rest. This abnormality in is reversed during contractile exercise, indicating that the most likely explanation is a vasodilator-vasoconstrictor imbalance and not from impaired erythrocyte rheology from sickling. Our results also indicate that CEU is likely to be useful as a biologic readout for microvascular abnormalities in future studies that examine the complications and treatment of SCD in animal models and patients.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Lindner is supported by grants R01-HL078610 and R01-HL111969 from the NIH, and a grant from the Doris Duke Foundation. Dr. Wu is supported by grant T32-HL-94294-5 from the NIH. Dr. Linden is supported by grants R01-HL111969 and R01-HL095704 from the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frenette PS, Atweh GF. Sickle cell disease: Old discoveries, new concepts, and future promise. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:850–858. doi: 10.1172/JCI30920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010;376:2018–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebbel RP, Osarogiagbon R, Kaul D. The endothelial biology of sickle cell disease: Inflammation and a chronic vasculopathy. Microcirculation. 2004;11:129–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sparkenbaugh E, Pawlinski R. Interplay between coagulation and vascular inflammation in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2013;162:3–14. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood KC, Hsu LL, Gladwin MT. Sickle cell disease vasculopathy: A state of nitric oxide resistance. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1506–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu C, Zhao W, Christ GJ, Gladwin MT, Kim-Shapiro DB. Nitric oxide scavenging by red cell microparticles. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:1164–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mack AK, Kato GJ. Sickle cell disease and nitric oxide: A paradigm shift? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1237–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato GJ, Hebbel RP, Steinberg MH, Gladwin MT. Vasculopathy in sickle cell disease: Biology, pathophysiology, genetics, translational medicine, and new research directions. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:618–625. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei K, Jayaweera AR, Firoozan S, Linka A, Skyba DM, Kaul S. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with ultrasound-induced destruction of microbubbles administered as a constant venous infusion. Circulation. 1998;97:473–483. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson D, Vincent MA, Barrett EJ, Kaul S, Clark A, Leong-Poi H, et al. Vascular recruitment in skeletal muscle during exercise and hyperinsulinemia assessed by contrast ultrasound. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282:E714–E720. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00373.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rim SJ, Leong-Poi H, Lindner JR, Wei K, Fisher NG, Kaul S. Decrease in coronary blood flow reserve during hyperlipidemia is secondary to an increase in blood viscosity. Circulation. 2001;104:2704–2709. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chadderdon SM, Belcik JT, Smith E, Pranger L, Kievit P, Grove KL, et al. Activity restriction, impaired capillary function, and the development of insulin resistance in lean primates. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303:E607–E613. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00231.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabry ME, Nagel RL, Pachnis A, Suzuka SM, Costantini F. High expression of human beta s- and alpha-globins in transgenic mice: Hemoglobin composition and hematological consequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:12150–12154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pascotto M, Leong-Poi H, Kaufmann B, Allrogen A, Charalampidis D, Kerut EK, et al. Assessment of ischemia-induced microvascular remodeling using contrast-enhanced ultrasound vascular anatomic mapping. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20:1100–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teichholz LE, Kreulen T, Herman MV, Gorlin R. Problems in echocardiographic volume determinations: Echocardiographic-angiographic correlations in the presence of absence of asynergy. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37:7–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biesiada G, Krzemien J, Czepiel J, Teleglow A, Dabrowski Z, Spodaryk K, et al. Rheological properties of erythrocytes in patients suffering from erysipelas. Examination with lorca device. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2006;34:383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagel RL, Fabry ME. The panoply of animal models for sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2001;112:19–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasgupta T, Hebbel RP, Kaul DK. Protective effect of arginine on oxidative stress in transgenic sickle mouse models. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:1771–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace KL, Linden J. Adenosine a2a receptors induced on inkt and nk cells reduce pulmonary inflammation and injury in mice with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;116:5010–5020. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-290643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Secomb TW, Pries AR. Blood viscosity in microvessels: Experiment and theory. Comptes rendus. Physique. 2013;14:470–478. doi: 10.1016/j.crhy.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pries AR, Secomb TW, Gaehtgens P. Biophysical aspects of blood flow in the microvasculature. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:654–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shim CY, Kim S, Chadderdon S, Wu M, Qi Y, Xie A, et al. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids mediate insulin-mediated augmentation in skeletal muscle perfusion and blood volume. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;307:E1097–E1104. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00216.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angerio AD, Lee ND. Sickle cell crisis and endothelin antagonists. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2003;26:225–229. doi: 10.1097/00002727-200307000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werdehoff SG, Moore RB, Hoff CJ, Fillingim E, Hackman AM. Elevated plasma endothelin-1 levels in sickle cell anemia: Relationships to oxygen saturation and left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Hematol. 1998;58:195–199. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199807)58:3<195::aid-ajh6>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Womack L, Peters D, Barrett EJ, Kaul S, Price W, Lindner JR. Abnormal skeletal muscle capillary recruitment during exercise in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and microvascular complications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2175–2183. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]