Abstract

Background

White matter (WM) injury is common after neonatal cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). We have demonstrated that the inflammatory response to CPB is an important mechanism of WM injury. Microglia are brain-specific immune cells that respond to inflammation and can exacerbate injury. We hypothesized that microglia activation contributes to WM injury caused by CPB.

Methods

Juvenile piglets were randomly assigned to one of three CPB-induced brain insults (1: no-CPB, 2: full-flow CPB, 3: CPB/Circulatory-arrest). Neurobehavioral tests were performed. Animals were sacrificed 3-days or 4-weeks post-operatively. Microglia and proliferating cells were immunohistologically identified. Seven analyzed WM regions were further categorized into 3-fiber connections (1: Commissural, 2: Projection, 3: Association fibers).

Results

Microglia numbers significantly increased on day 3 after CPB/Circulatory-arrest, but not after full-flow CPB. Fiber categories did not affect these changes. On post-CPB week 4, proliferating cell number, blood leukocyte number and IL-6 levels, and neurological scores had normalized. However, both full-flow CPB and CPB/Circulatory-arrest displayed significant increases in the microglia number compared with Control. Thus brain-specific inflammation after CPB persists despite no changes in systemic biomarkers. Microglia number was significantly different among fiber categories, being highest in Association and lowest in Commissural connections. Thus there was a WM fiber-dependent microglia reaction to CPB.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates prolonged microglia activation in WM after CPB. This brain-specific inflammatory response is systemically silent. It is connection fiber-dependent which may impact specific connectivity deficits observed after CPB. Controlling microglia activation after CPB is a potential therapeutic intervention to limit neurological deficits following CPB.

Keywords: Brain, CPB, Inflammation, Neonate, Hypothermia/circulatory arrest

INTRODUCTION

The hospital mortality of severe/complex congenital heart disease (CHD) has been dramatically reduced in the last 2 decades from more than 50% to less than 10% [1]. However, many of these children suffer some form of neurological impairment [2 3]. The most common neurological deficits seen in infants after CHD repair are fine/gross motor deficits [4 5]. These symptoms are consistent with diffuse white matter (WM)-injury [6]. Recent MRI studies have demonstrated a high incidence of WM-injury after surgery (25–55%) in the neonate and infant with CHD [7–10]. Impairment of neural connectivity due to WM-injury causes a wide range of neurological dysfunction including attention deficit, hyperactivity, executive dysfunction, impairment of working memory, and verbal dysfunction [11–13]. These impairments are remarkably similar to deficits observed in children with severe/complex CHD [2 14 15]. Altered WM microstructure has also been identified in adolescents with CHD [16] in whom deficits of cognitive/behavioral functions have been documented [14]. Furthermore, it is well known that following premature birth alterations of the WM microstructure persist into later life [17]. In summary the extent of abnormal WM development early in life likely accounts for the type and degree of neurological deficits observed in CHD.

Causes of neurological morbidity associated with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) include an exaggerated systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), as well as risk of ischemia-reperfusion and reoxygenation injury (I/R-injury) [18 19]. Our previous studies have shown that reduction of systemic inflammation is important to minimize the risk of WM-injury [20]. On the other hand, the brain is an organ known to be “immune privileged”. The blood–brain barrier of the cerebrovascular endothelium and its participation in the complex structure of the neurovascular unit restrict access of immune cells and immune mediators to the central nervous system (CNS) [21]. Microglia are the resident CNS immune cells and active surveyors of the extracellular environment, playing a central role in neural immune function in reacting to a wide variety of insults [22]. In addition, recent studies have demonstrated that in the developing brain microglia regulate neuronal circuit development by triggering programmed cell death and stripping off synapses in an activity-dependent fashion [23]. Importantly activation of microglia by cerebral inflammation causes substantial loss of synapses, which results in sustained deficits in synaptic connectivity [24 25]. These new findings highlight the importance of microglia for CNS development and function. The observations led our hypothesis that microglia activation is an important component of WM-injury caused by CPB. The aim of the present study is to define the acute and long-term cellular response of microglia to CPB in defined WM regions using a porcine CPB survival model.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Experimental Model

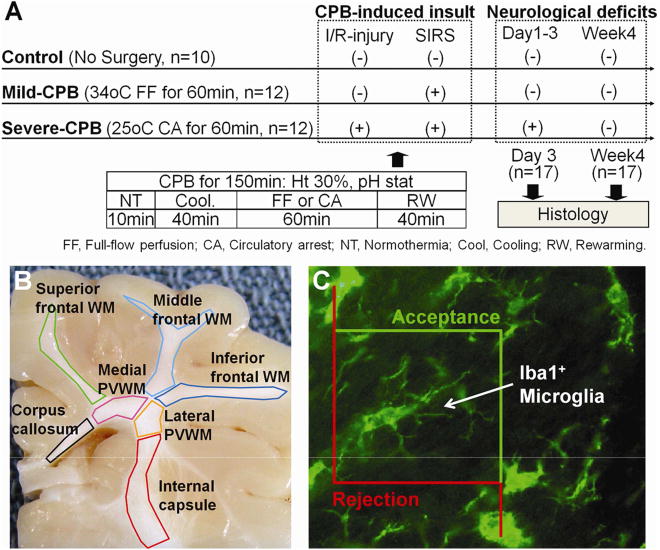

A total of 34 three-week-old female Yorkshire piglets were involved in this study. To investigate the effects of CPB we distinguished CPB-induced brain insults into SIRS and I/R-injury. Animals were randomly assigned to one of 3 CPB-induced brain insults: i) no-CPB (Control: No-insult n=10); ii) 34°C-full-flow CPB for 60min (Mild-CPB: SIRS n=12); and iii) 25°C-circulatory-arrest for 60min (Severe-CPB: SIRS with I/R injury n=12). After initial normothermic perfusion, animals were cooled and then circulatory arrest or full-flow bypass was chosen according to the protocol (Fig. 1A). The heterologous blood was used to maintain the hematocrit level of 30% (Table 1). For cooling and rewarming pH-stat strategy was performed to employ the current standard CPB technique. Cerebral tissue oxygen index (TOI) was measured by Near-Infrared spectroscopy (NIRO-300) and used to determine ischemic status. SIRS was identified by the leukocyte number and plasma IL-6 concentration. We performed all experiments in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory animals. The study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Children’s National Medical Center. The details of the experimental model have been described previously [20].

Figure 1.

A, Study design. B, Subdivision of cerebral WM. C, Iba1+ microglia cell and the counting frame for analysis. Microglia is counted if it lies entirely within the counting frame or if it touches an acceptance line without touching a rejection line.

Table 1.

Experimental Conditions

| Control (n=10) Mean |

SD | Mild-CPB (n=12) Mean |

SD | Severe-CPB (n=12) Mean |

SD | F-test | p value | Control vs. Mild |

Control vs. Severe |

Mild vs. Severe |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) | |||||||||||

| Pre OP | 4.9 | 0.6 | 5.1 | 0.8 | 4.8 | 0.7 | 0.687 | 0.5108 | |||

| POD3 | 5.0 | 0.6 | 5.1 | 0.9 | 4.8 | 0.9 | 0.586 | 0.5631 | |||

| Week4 | 10.5 | 2.4 | 9.3 | 1.6 | 9.6 | 2.0 | 0.460 | 0.6467 | |||

| MAP (mmHg) | |||||||||||

| Pre OP | 87.3 | 6.9 | 84.3 | 17.8 | 82.5 | 16.8 | 0.230 | 0.7961 | |||

| End of CPB | 81.8 | 11.1 | 89.4 | 25.9 | 87.3 | 25.1 | 0.231 | 0.7950 | |||

| 3h CPB | 81.0 | 17.3 | 82.3 | 17.7 | 85.2 | 10.6 | 0.158 | 0.8544 | |||

| Hematocrit (%) | |||||||||||

| Pre OP | 36.6 | 2.9 | 35.4 | 3.6 | 37.3 | 2.6 | 1.395 | 0.2629 | |||

| End of CPB | 35.5 | 3.6 | 33.1 | 2.5 | 35.5 | 2.9 | 2.662 | 0.0858 | |||

| 3h CPB | 35.6 | 4.3 | 35.2 | 4.4 | 33.6 | 3.3 | 0.787 | 0.4642 | |||

| TOI (%) | |||||||||||

| Pre OP | 48.6 | 4.3 | 49.3 | 3.5 | 49.8 | 2.3 | 0.356 | 0.7035 | |||

| Minimum during CPB | 48.8 | 4.0 | 57.5 | 2.8 | 32.9 | 3.7 | 154.480 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| End of CPB | 50.2 | 5.4 | 53.9 | 4.4 | 52.9 | 3.4 | 1.849 | 0.1749 | |||

| Leukocyte (×1000/μL) | |||||||||||

| Maximum during CPB | 9.2 | 2.6 | 18.9 | 4.6 | 20.9 | 4.3 | 13.949 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | <.0001 | 0.2833 |

| POD3 | 8.7 | 2.4 | 11.4 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 3.3 | 1.300 | 0.3035 | |||

| Week4 | 14.6 | 9.5 | 15.5 | 8.5 | 15.0 | 6.7 | 0.013 | 0.9866 | |||

| Plasma IL-6 (pg/ml) | |||||||||||

| Maximum during CPB | 0.0 | 212.6 | 142.5 | 275.8 | 173.2 | 6.320 | 0.0062 | 0.0119 | 0.0017 | 0.3156 | |

| POD3 | 9.3 | 20.7 | 132.9 | 120.9 | 110.8 | 153.6 | 1.678 | 0.2221 | |||

| Week4 | 7.4 | 16.5 | 8.1 | 12.7 | 4.8 | 6.2 | 0.102 | 0.9033 | |||

| Total NDS | |||||||||||

| POD1-3 | 0.0 | 20.9 | 24.7 | 348.0 | 188.2 | 33.254 | <.0001 | 0.6603 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| Week2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 99.2 | 87.2 | 7.029 | 0.0077 | 0.0072 | 0.0053 | |||

| Week3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 35.0 | 85.7 | 0.906 | 0.4266 | |||||

| Week4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

CPB; cardiopulmonary bypass, MAP; mean arterial pressure, NDS; neurological deficit score, OP; operation, POD; post-operative day, SD; standard deviation, TOI; tissue oxygen index

Neurological Outcome

Neurological and behavioral evaluations were performed at 24 hour intervals. In the system a score of 100 is assigned to each of 4 general components. A total score of 400 indicates brain death while a score of 0 is considered normal.

Cellular Analysis

The brain was harvested after transarterial infusion of 2.0-liter normal saline followed by 2.0-liter 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline through the common carotid artery (Fig. 1A). Microglia and proliferating cells in the WM were identified using specific antibodies to Iba1 and Ki67. For cellular analysis, porcine WM was subdivided into seven regions: (1) corpus callosum; (2) internal capsule; (3) medial and (4) lateral periventricular WMs; and (5) superior, (6) middle, and (7) inferior frontal WMs (Fig. 1B). Each WM structure was further categorized into three fiber categories including commissural (body of corpus callosum), projection (internal capsule and medial/lateral periventricular WMs), and association fibers (superior/middle/inferior frontal WMs) based on diffusion tensor imaging in the porcine brain and human neonate WM atlas. Commissural fibers cross from one cerebral hemisphere to the other. Projection fibers unite the cortex with the brain stem or spinal cord. Association fibers connect different regions within the same hemisphere of the brain. To determine cell density, a stereology microscope (Stereo Investigator) was used to identify antibody-positive cells. The system provides systematic random sampling to obtain unbiased estimates of cell number (Fig. 1C).

Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons was used to detect differences in immunohistochemistical analysis and neurological deficit score between experimental conditions. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni comparisons was also used to evaluate changes of cell numbers between WM regions and CPB groups. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software package (version 18.0, SPSS Inc/IBM, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Bypass induced Ischemia-reperfusion and Reoxygenation Result in Acute Microglia Activation in All White Matter Regions

There were no differences between three CPB groups in pre-operative conditions (Table 1). Minimum value of TOI during bypass in Severe-CPB was significantly lower than in Control and Mild-CPB, while Mild-CPB induced higher TOI compared with Control (Table 1). The result confirmed that I/R injury with SIRS is the predominant mechanism of insult in Severe-CPB (Fig. 1A). Mild- and Severe-CPB insults caused a significant increase of leukocyte numbers and plasma IL-6 concentration; while there was no differences for both between the two CPB groups (Table 1, Fig. 1A). Severe-CPB insults caused acute neurological deficits compared with Control; conversely, Mild insults did not induce neurological deficits (Table 1, Fig. 1A). Neurological symptoms after Severe-CPB improved with time and were not detected on postoperative week 4 (Table 1, Fig. 1A).

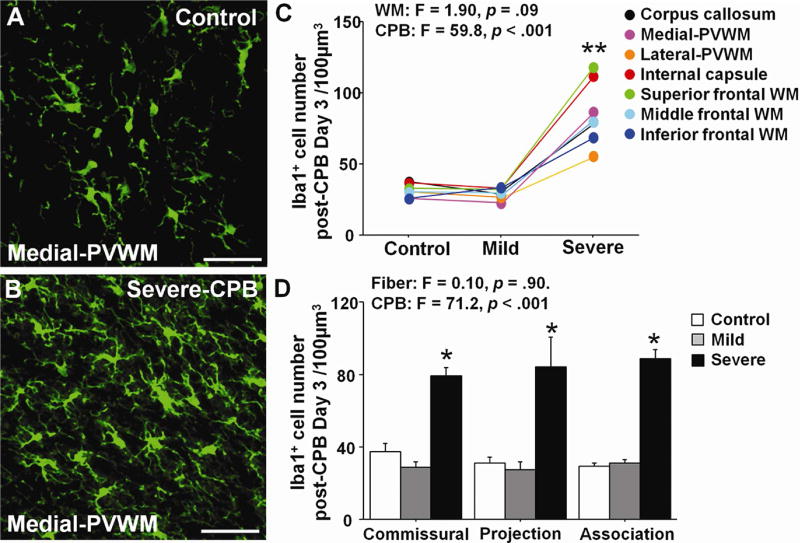

Microglia activation was first assessed by evaluating the number of Iba1+ cells on post-operative day 3. Iba1+ microglia numbers significantly increased in all WM regions following Severe-CPB, as compared with Control, but not following Mild-CPB (Fig. 2A–C). Microglia were also activated by insults due to Severe-CPB as defined by morphological phenotype (Fig. 2A,B). Both analyzed WM regions and fiber categories did not affect these changes (Fig. 2C,D). Taken together, these results indicate that SIRS due to CPB did not cause acute microglia activation; whereas CPB-induced I/R injury with SIRS resulted in microglia activation in all WM regions.

Figure 2. Cardiopulmonary bypass induced cerebral ischemia-reperfusion/reoxygenation result in acute microglia activation.

A,B, Iba1+ microglia in Control (A) and after Severe-CPB (B). C, Iba1+ microglia cell number in seven WM regions on post-CPB day 3. D, Iba1+ microglia cell number in three fiber categories on post-CPB day 3. * p < .001 vs. Control and Mild by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni comparisons. ** p < .001 vs. Control and Mild by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni comparisons. Scale bar, 50μm. Data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (C,D; n=5–6 each).

Area-dependent Microglia Activation after CPB Persists Despite no Changes in Systemic Biomarkers

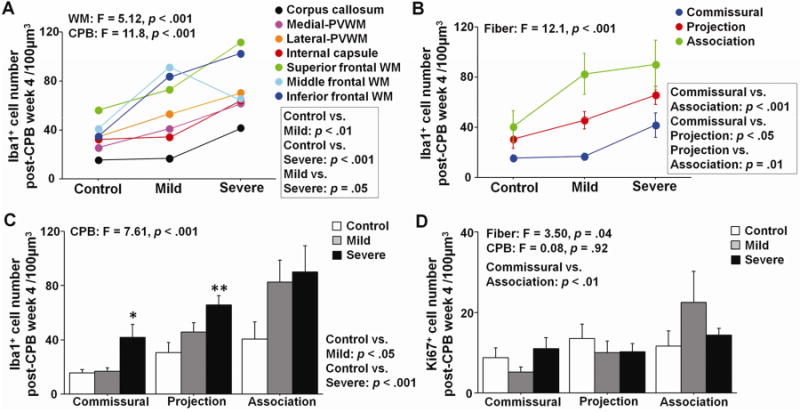

To assess the long-term effects of CPB on WM microglia activation, we analyzed changes in microglia cells at 4 weeks postoperatively. The total number of Iba1+ cells was significantly affected by CPB and varied between WM regions (Fig. 3A). Although Mild-CPB did not cause microglia activation on day 3 (Fig. 2C,D), both Mild- and Severe-CPB groups displayed significant increases in the microglia number on post-CPB week 4 compared with Control (Fig. 3A,C). At 4 weeks after CPB, however, blood leukocyte number, IL-6 levels, and neurological scores had all normalized in Mild- and Severe-CPB (Table 1). The findings suggest that microglia activation after cardiac surgery persists despite no changes in clinically-relevant systemic biomarkers. We also observed that in analyzed WM regions there were no differences in Ki67+ proliferating cell numbers between three CPB groups (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the proliferation of microglia occurs in the earlier time period. The number of Iba1+ cells after CPB insult also varied in three distinct WM fibers, being highest in the association fiber and lowest in commissural connections (Fig. 3B). The results indicate fiber-specific reactive microgliosis after CPB.

Figure 3. Prolonged microglia activation after cardiopulmonary bypass is area-dependent.

A, Iba1+ microglia cell number in seven WM regions on post-CPB week 4. B,C, Iba1+ microglia cell number in three fiber categories on post-CPB week 4. D, Ki67+ proliferating cell number in three fiber categories on post-CPB week 4. * p = .01 vs. Control, ** p < .01 vs. Control by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni comparisons. Data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (n=5–6 each).

Microglia Reaction to CPB is Area Dependent and Varies According to Brain Insults

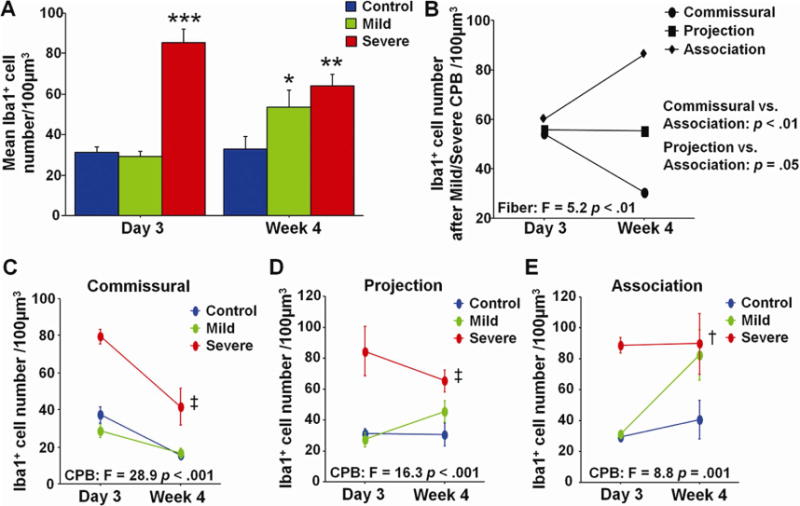

The change of Iba1+ microglia numbers from day 3 to week 4 was also investigated. Mild-CPB significantly increased cell number from day 3 to week 4 while there was a reduction in the number after Severe-CPB (Fig. 4A). When the change was compared in 3 fiber categories, it significantly differed according to both WM fibers and CPB insults (Fig. 4B–E). Severe-CPB reduced microglia cell number from day 3 to week 4 in commissural fiber (Fig. 4C) while projection and association fibers displayed no significant differences in the number after Severe-CPB (Fig. 4D,E). Mild-CPB reduced cell number from day 3 to week 4 in commissural fiber as observed in Severe-CPB (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, a significant increase in microglia was found in association fiber after Mild-CPB (Fig. 4E). Altogether, our results demonstrate that microglia reaction to CPB is area-dependent and varies according to CPB-induced brain insults.

Figure 4. Microglia reaction to cardiopulmonary bypass is area-dependent and varies according to brain insults.

A, Mean Iba1+ microglia cell number on post-CPB day 3 and week 4. B, Change of Iba1+ microglia cell number after CPB in three fiber categories. C–E, Change of Iba1+ microglia cell number in commissural (C), projection (D), and association (E) fibers. * p = .05 vs. Control, ** p < .01 vs. Control, *** p < .001 vs. Control and Mild by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni comparisons. † p = .05, ‡ p < .001 vs. Control and Mild by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni comparisons. Data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (n=5–6 each).

COMMENT

This study is the first to define acute and long-term cellular responses of WM microglia to CPB-induced brain insults using a porcine animal model that is anatomically and physiologically close to humans. Our analysis has identified prolonged microglia activation in WM at 4 weeks postoperatively. Importantly this brain-specific inflammatory response after CPB persists despite no changes in clinically-relevant systemic biomarkers. We have also demonstrated that the reactive microgliosis after CPB varies according to WM connection fibers.

Because of reduced mortality after complex pediatric cardiac surgery, a current challenge is to reduce/eliminate long-term sequelae, particularly neurodevelopmental delays [26]. Achieving this goal will require an improved understanding of the effects of CPB on developing WM [27]. Resident brain-specific immune cells – microglia – were shown to play important roles in normal brain development [23 24]. However little has been known regarding the response of WM microglia to CPB. Here we demonstrate that Severe-CPB insults result in acute microglia activation and both Mild- and Severe-CPB cause a prolonged increase in microglia numbers. In this study CPB-induced brain insults secondary to SIRS and I/R-injury were distinguished from insults secondary to SIRS alone as observed in the majority of patients after CPB [Mild-CPB (Full-flow CPB at 34°C)]. Our findings suggest that microglia activation occurs in many patients after cardiac surgery. Importantly blood leukocyte and IL-6 levels, as well as neurological scores had all normalized on post-CPB week 4, indicating that this brain-specific inflammatory response that likely exists in the majority of patients following CPB is systemically silent. Obvious technical/ethical hurdles have prevented the measurement of microglia activation in children with CHD. Therefore, the development of a new biomarker would be required to define microglia activation and treat it after surgery. Recent advances in brain imaging allow assessment of the inflammatory response in the human brain [28]. Although there are still limitations to these techniques [28], further development of neuromonitoring technology will assist in refining perioperative management in pediatric cardiac surgery.

In the present study the microglia reaction to CPB varies according to WM region and the connection fiber category. Within three fiber categories, association fiber displayed the highest number of microglia cells after CPB. A delayed microglia reaction after Mild-CPB insults is also observed in association fiber. In human WM, studies using diffusion tensor imaging have shown that association tracts continuously have a lower maturation degree in the first 2 years after birth as defined by fractional anisotropy [29]. Our results also confirm that fractional anisotropy of the association fiber was the lowest (i.e. the most immature) in porcine WM. Therefore the area-dependent microglia activation and delayed microglia reaction we observed in this study may represent changes of microglia response based on the maturation stage of WM. The underlying mechanism in area-dependent and/or maturation-dependent microglia activation is less understood. We have previously demonstrated that the blood-brain barrier is impaired by CPB [30]. Throughout development of the blood-brain barrier, sealing of interendothelial tight junctions is still an on-going process during brain maturation [31]. Therefore different developmental stages of the barrier function might affect increased permeability after CPB and allow accumulation of more toxic molecules or pro-inflamatory stimuli in the immature brain region, which in turn result in increased microglia activation. Our previous study has also shown that apoptotic oligodendrocyte number after CPB was inversely correlated with WM maturation stage, i.e. there are more apoptotic cells in immature WM [20]. Since microglia can become overactivated in response to neuronal and glial damage [32], maturation-dependent oligodendrocyte injury after CPB may cause area-dependent microglia activation after CPB.

Regardless of the initiating stimuli, reactive microgliosis can be toxic to neighboring neurons and glia producing proinflammatory factors and exacerbate WM-injury [32]. Microglia help regulate the development of axonal bundles and eliminate excessive projections in developing WM [33 34]. Therefore, in addition to causing a perpetuating cycle of cellular damage, excessive microgila response after CPB could alter important microglial functions for successful WM development in patients with CHD. Our findings imply that WM microglia activation occurs in many patients after cardiac surgery. WM connects various areas of the brain and is the critical structure for neural connectivity. Thus CPB-induced area-dependent/fiber-specific prolonged microgila reactions may be the cause of specific connectivity deficits observed in children with CHD. Controlling microglia activation after CPB, therefore, is a potential therapeutic intervention to limit neurological deficits in the CHD patient.

Preclinical study in a rodent model of resuscitation following cardiac arrest has demonstrated that deeper levels of hypothermia results in decrease of microglia activation [35]. Thus deep hypothermia may reduce CPB-induced microglia activation. Compared with a single ischemic event, however, mechanisms underlying brain insults during CPB/DHCA are highly complex and multietiologic [2]. In this study we were unable to define targeted conditions that will reduce microglia activation. We have developed a unique brain slice model that replicates specific brain conditions during CPB [36]. In contrast to a large animal model, the model allows us to study each factor individually and helps in our understanding of complex/multifactorial events on the developing brain [36]. In addition, brain slice models have been used widely for the development of pharmacological therapy. Therefore studies using both the mouse slice model and porcine CPB model will allow designing targeted therapies and conditions that will minimize the risk of CPB-induced microglia activation.

Overall neurological outcomes were quantified in this study; however, a lack of WM-dependent and/or connectivity-specific behavioral assays in a porcine model has prevented us from defining correlation between microglia activation and specific neurological deficits. The maturation pattern in porcine WM displays a similar progression to human WM [20]. Therefore, development of WM-specific neurobehavioral analysis in this model will assist in determining effects of WM-injury on neurodevelopmental deficits observed in children with CHD. Since little has been known regarding specific neurodevelopmental outcomes related to microglia activation in the human, the establishment of new behavioral tests in a porcine model will also contribute to our further understanding of the role of microglia in the developing WM. MRI studies have demonstrated a high incidence of WM-injury after pediatric cardiac surgery [7–10]: while the present study was unable to define whether and how microglia activation contributes to WM-injury defined by MRI. Future MRI studies in this model will also define effects of CPB-induced microglia activation on WM-injury, and provide insights of cellular mechanisms underlying neurodevelopmental deficits in children with CHD.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates for the first time prolonged microglia activation in WM after CPB using a porcine survival model. This brain-specific inflammatory response is systemically silent. Thus development of a specific biomarker would help in monitoring microglia activation and refining perioperative management in cardiac surgery to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with CHD. The reactive microgliosis after CPB is connection fiber-dependent which may impact specific connectivity deficits observed in patients with CHD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant R01HL104173, Baier Cardiac Research Funding and W.T. Gill Jr. Fellowship Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the 51st Annual Meeting of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, San Diego, CA, Jan 24–28, 2015.

References

- 1.Al-Radi OO, Harrell FE, Jr, Caldarone CA, et al. Case complexity scores in congenital heart surgery: a comparative study of the Aristotle Basic Complexity score and the Risk Adjustment in Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS-1) system. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133(4):865–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wernovsky G. Current insights regarding neurological and developmental abnormalities in children and young adults with complex congenital cardiac disease. Cardiol Young. 2006;16(Suppl 1):92–104. doi: 10.1017/S1047951105002398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabbutt S, Gaynor JW, Newburger JW. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after congenital heart surgery and strategies for improvement. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2012;27(2):82–91. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328350197b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellinger DC, Jonas RA, Rappaport LA, et al. Developmental and neurologic status of children after heart surgery with hypothermic circulatory arrest or low-flow cardiopulmonary bypass. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):549–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newburger JW, Sleeper LA, Bellinger DC, et al. Early developmental outcome in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and related anomalies: the single ventricle reconstruction trial. Circulation. 2012;125(17):2081–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.064113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volpe JJ. Hypoxic-ischemic enchephalopathy: Biochemical and Physiological aspects. 5. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galli KK, Zimmerman RA, Jarvik GP, et al. Periventricular leukomalacia is common after neonatal cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127(3):692–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller SP, McQuillen PS, Hamrick S, et al. Abnormal brain development in newborns with congenital heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(19):1928–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andropoulos DB, Hunter JV, Nelson DP, et al. Brain immaturity is associated with brain injury before and after neonatal cardiac surgery with high-flow bypass and cerebral oxygenation monitoring. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139(3):543–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beca J, Gunn JK, Coleman L, et al. New white matter brain injury after infant heart surgery is associated with diagnostic group and the use of circulatory arrest. Circulation. 2013;127(9):971–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullen KM, Vohr BR, Katz KH, et al. Preterm birth results in alterations in neural connectivity at age 16 years. Neuroimage. 2011;54(4):2563–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lubsen J, Vohr B, Myers E, et al. Microstructural and functional connectivity in the developing preterm brain. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35(1):34–43. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fields RD. White matter in learning, cognition and psychiatric disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(7):361–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellinger DC, Wypij D, Rivkin MJ, et al. Adolescents with d-transposition of the great arteries corrected with the arterial switch procedure: neuropsychological assessment and structural brain imaging. Circulation. 2011;124(12):1361–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.026963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeMaso DR, Labella M, Taylor GA, et al. Psychiatric Disorders and Function in Adolescents with d-Transposition of the Great Arteries. J Pediatr. 2014;165(4):760–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivkin MJ, Watson CG, Scoppettuolo LA, et al. Adolescents with d-transposition of the great arteries repaired in early infancy demonstrate reduced white matter microstructure associated with clinical risk factors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146(3):543–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ment LR, Hirtz D, Huppi PS. Imaging biomarkers of outcome in the developing preterm brain. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(11):1042–55. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70257-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy JH, Tanaka KA. Inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(2):S715–20. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04701-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jonas RA. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest: current status and indications. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2002;5:76–88. doi: 10.1053/pcsu.2002.31493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishibashi N, Scafidi J, Murata A, et al. White matter protection in congenital heart surgery. Circulation. 2012;125(7):859–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.048215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muldoon LL, Alvarez JI, Begley DJ, et al. Immunologic privilege in the central nervous system and the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(1):13–21. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanisch UK, Kettenmann H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(11):1387–94. doi: 10.1038/nn1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wake H, Moorhouse AJ, Miyamoto A, et al. Microglia: actively surveying and shaping neuronal circuit structure and function. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36(4):209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tremblay ME, Stevens B, Sierra A, et al. The role of microglia in the healthy brain. J Neurosci. 2011;31(45):16064–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4158-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schafer DP, Stevens B. Phagocytic glial cells: sculpting synaptic circuits in the developing nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23(6):1034–40. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaltman JR, Andropoulos DB, Checchia PA, et al. Report of the pediatric heart network and national heart, lung, and blood institute working group on the perioperative management of congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2010;121(25):2766–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.913129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McQuillen PS, Miller SP. Congenital heart disease and brain development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1184:68–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciccarelli O, Barkhof F, Bodini B, et al. Pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis: insights from molecular and metabolic imaging. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(8):807–22. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geng X, Gouttard S, Sharma A, et al. Quantitative tract-based white matter development from birth to age 2years. Neuroimage. 2012;61(3):542–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okamura T, Ishibashi N, Zurakowski D, et al. Cardiopulmonary bypass increases permeability of the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89(1):187–94. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obermeier B, Daneman R, Ransohoff RM. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med. 2013;19(12):1584–96. doi: 10.1038/nm.3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(1):57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rochefort N, Quenech’du N, Watroba L, et al. Microglia and astrocytes may participate in the shaping of visual callosal projections during postnatal development. Journal of physiology, Paris. 2002;96(3–4):183–92. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(02)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mallard C, Davidson JO, Tan S, et al. Astrocytes and microglia in acute cerebral injury underlying cerebral palsy associated with preterm birth. Pediatr Res. 2014;75(1–2):234–40. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drabek T, Tisherman SA, Beuke L, et al. Deep hypothermia attenuates microglial proliferation independent of neuronal death after prolonged cardiac arrest in rats. Anesth Analg. 2009;109(3):914–23. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181b0511e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murata A, Agematsu K, Korotcova L, et al. Rodent brain slice model for the study of white matter injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146(6):1526–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]