Abstract

Autophagy and redox biochemistry are two major sub disciplines of cell biology which are both coming to be appreciated for their paramount importance in the etiology of neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Thus far, however, there has been relatively little exploration of the interface between autophagy and redox biology. Autophagy normally recycles macro-molecular aggregates produced through oxidative-stress mediated pathways, and also may reduce the mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species through recycling of old and damaged mitochondria. Conversely, dysfunction in autophagy initiation, progression or clearance is evidenced to increase aggregation-prone proteins in neural and extraneural tissues. Redox mechanisms of autophagy regulation have been documented at the level of cross-talk between the Nrf2/Keap1 oxidant and electrophilic defense pathway and p62/sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1)-associated autophagy, at least in extraneural tissue; but other mechanisms of redox autophagy regulation doubtless remain to be discovered and the relevance of such processes to maintenance of neural homeostasis remain to be determined. This review summarizes current knowledge regarding the relationship of redox signaling, autophagy control, and oxidative stress as these phenomena relate to neurodegenerative disease. AD is specifically addressed as an example of the theme and as a promising indication for new therapies that act through engagement of autophagy pathways. To exemplify one such novel therapeutic entity, data is presented that the antioxidant and neurotrophic agent lanthionine ketimine-ethyl ester (LKE) affects autophagy pathway proteins including beclin-1 in the 3xTg-AD model of Alzheimer’s disease where the compound has been shown to reduce pathological features and cognitive dysfunction.

Keywords: Autophagy, Alzheimer’s disease, beclin, brain, lanthionine, LC3, neuroinflammation, Nrf2/Keap1, redox biology, reactive oxygen species, sequestosome

Introduction

There exists a common constellation of phenomena shared across very disparate neurodegenerative pathologies which includes accumulation of long-lived protein aggregates; exacerbated oxidative stress; chronic neuroinflammation; and progressive impairment of cytoskeletal structure and function causing die-back of neuritic arbors. Often, excitotoxic neurotransmission and mitochondrial dysfunction are discussed as part of this patho-biochemical composite. The commonality of these features might lead one to suspect fundamental pathophysiological processes underlie different neurological diseases such that treatments aimed at a basic enough level might find broad clinical utility. To date, however, efforts to formulate a unified theory of neurodegenerative pathology have met with little success. This failure is due in part to difficulties of ordering and causally relating the various components: Increased oxidative stress, for instance, can increase the volume of redox-sensitive signal transduction to stimulate neuroinflammation (Gabbita et al., 2000) while also contributing to protein aggregation (Caballero and Coto-Montes, 2014; Giordano et al., 2014; Norris and Giasson, 2005). Viewed another way however, neuroinflammatory events might precede and give rise to the other common neurodegenerative hallmarks (Gabbita et al., 2000; Hensley et al., 2006; Hensley et al., 2010a). This quandary is somewhat akin to the question of the “chicken or the egg” and is likewise solved, on one level: Neurodegenerative disease etiology is a non-linear processes involving many common starting points with a handful of key features interacting reciprocally and dynamically to produce variations on a common final, neurodegenerative outcome. Such an explanation is not, however, intellectually pleasing and neither does it offer a discrete cellular pathway that might be modulated generally for improving neural health.

In this review we posit that one additional component should be prominently added to the generally-recognized constellation of cellular pathways that is widely associated with spontaneous neurodisease, this being the phenomenon of cellular macro-autophagy. Autophagy is a special type of pre-lysosomal program allowing collection of large proteins, complexes and even whole organelles which are subsequently degraded within a specialized autophagolysosome. As such autophagy is distinct from the two other main forms of proteolytic turnover, proteosomal degradation and non-autophagic lysosomal hydrolysis. It is herein argued that autophagy is one of the most fundamental processes that could relate most (or all) of the other common cellular hallmarks of neurodegenerative disease, and that an especially close reciprocal interaction exists between autophagy and redox cell biology. If such a hypothesis is borne out experimentally, then new strategies aimed at the nexus between autophagy and redox biology could yield conceptually new therapeutic approaches to treat broad classes of brain disease.

The mechanics of autophagy

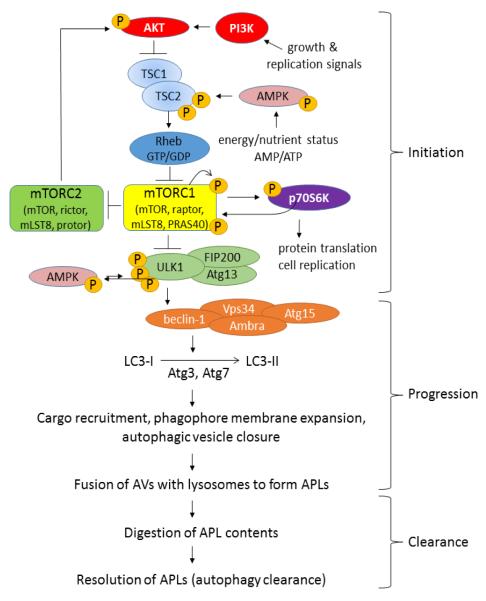

Macro-autophagy, the most common type of autophagy (hereafter termed simply “autophagy” unless otherwise specified) is a process by which target proteins are engulfed in double-lumen membranes called autophagosomes (also known as autophagic vesicles; AVs) that merge with lysosomes to form mature, acidic, digestive organelles called autophagolysosomes (APLs) (Dall’Armi et al., 2013; Gallagher and Chan, 2013; Klionsky et al., 2005; Ravikumar et al., 2010). Autophagy is a complex process involving literally scores of structural and regulatory proteins, but predominant amongst its regulatory elements are the mammalian target of rapamycin complex-1 (mTORC1) and unc-51-like kinase-1 (ULK1) (Gallagher and Chan, 2013; Ravikumar et al., 2010; Wirth et al., 2008). Perhaps the easiest way to visualize autophagy is to separate the process into “upstream” initiation control, above the level of ULK1; and “downstream” control, past the level of ULK1 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Macro-autophagy can be visualized as discrete processes of initiation, progression and clearance.

The initial phases of autophagy, which we term “initiation” level steps, are regulated on several levels. First, these steps are strongly regulated by protein kinase cascades and reciprocally by protein phosphatases which represent a well-known, redox-sensitive aspect of cellular signal transduction. Second, mTOR is regulated by a guanine nucleotide exchange mechanism involving the small GTPase, Rheb, and the GAP complex TSC1/2 as described in the text. Third, mTORC1 and TSC1/2 are regulated by cellular localization by concentration on the external lysosome vs. distribution near the cell perimeter. When mTORC1 is relatively inhibited, ULK1 protein kinase becomes activated, triggering formation of phagophores (early autophagic vesicles) in a process involving beclin-1, the class-III phosphatidylinositol-III kinase (PI3K) VPS34, and microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (Atg8/MAP1-LC3/LC3) or GABARAP homologs (see Fig. 2). Maturation and delipidation of Atg8/LC3 are dynamically controlled by redox-sensitive thiol protease Atg4, while kinase cascades impinging upon mTOR, beclin-1 and ULK-1 complexes may be regulated through both reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. After maturation and fusion with lysosomes to form autophagosomes (autophagolysosomes or APLs), the autophagic process completes and the APLs are cleared. The progression and clearance phases of autophagy offer further opportunities for redox regulation and vulnerabilities for failure in response to protracted oxidative stress. Redox processes may positively or negatively regulate discrete levels of autophagy, depending on magnitude and duration of the redox challenge and other ambient cellular circumstances.

As illustrated in Figure 1, mTORC1 is itself a complex of mTOR kinase and various structural and regulatory proteins that together regulate key proteins including p70S6 kinase and ULK1 (Jewell et al., 2013; Gallagher and Chan, 2013; Wirth et al., 2008). When nutrients (particularly, branched chain amino acids) and energy are plentiful, mTORC1 is constitutively “on”. Active mTORC1 phosphorylates p70S6 kinase which in turn stimulates protein synthesis at the ribosome and favors anabolic processes and cell proliferation. Concomitantly mTORC1 activates mTORC2 (which consists of the same mTOR as mTORC1 but a different set of associated regulatory components) (Huang and Fingar, 2014). mTORC2 in turn affects anabolic processes such as lipid synthesis; metabolism, favoring cellular proliferation; and actin microfilament dynamics (Huang et al., 2014). Active mTORC1 also phosphorylates uncoordinated-like kinase-1 (ULK1) in a pattern that deactivates ULK1 and prevents downstream autophagic processes from initiating.

When nutrients are scarce, mTORC1 itself becomes suppressed by the coordinated actions of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) proteins 1 and 2 (TSC1/2) and Rheb (Ras homolog enriched in brain). Specifically Rheb is a GTPase that inhibits mTORC1 when bound to GTP (Groenewoud and Zwartkuis, 2013; Ravikumar et al., 2010). TSC1/2 serve as guanylase-activating proteins (GAPs) to accelerate GTP hydrolysis, thus de-activating mTORC1 and dys-inhibiting autophagy (i.e. TSCs ultimately activate as pro-autophagic proteins in their default state). TSC proteins, in turn, are regulated by nutrient-sensing machinery and proximally by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). TSCs also receive input from growth-factor responsive AKT/protein-kinase B pathways and from stress-activated protein pathways (Jewell et al., 2013). From the preceding discussion it is clear that cellular anabolism and cellular catabolism are dynamically and reciprocally regulated by opposing pathways with mTORC1 and mTORC2 at their respective cores.

When mTORC1 is deactivated via TSC1/2, this causes disinhibition of ULK1 which then associates with beclin-1 protein (Atg6) to initiate formation of pre-autophagosomal structures (phagophores) at phagosome-activating sites (PAS), that probably bud off the endoplasmic reticulum (Gallagher and Chan, 2013; Ravikumar et al., 2010; Wirth et al., 2008) (Fig. 2). ULK1 acts on beclin-1 either directly or through other members of an ULK1/FIP200/Atg-1 complex (Ravikumar et al., 2010). In any case, ULK1 activation prompts beclin-1 (Atg-6) to associate with the class-III phosphatidylinositol-III kinase (PI3K), VPS34; Barkor (Atg14); and p150/Vps15 to form the core of an autophagy-regulating macromolecular complex (Ravikumar et al., 2010). Other proteins including AMBRA and UVRAG may bind and modulate the activity of this beclin-1 / PI3K complex (Ravikumar et al., 2010). Particularly, beclin-1 also binds the apoptosis-inhibiting Bcl2 and Bcl-XL proteins in a competitive fashion such that strong stimulation of beclin-1 dependent autophagy frees these Bcl proteins. The beclin-1 / ULK1 level of autophagy control represents one likely point where oxidative stress can affect or disrupt normal autophagy regulation: For instance, Sarkar et al. (2011) have presented evidence that nitric oxide inhibition of the JNK1 kinase reduces Bcl-2 phosphorylation and increases the Bcl-2-beclin 1 interaction thus inhibiting autophagy at this level. Evidently, there exists something of a reciprocal interaction whereby apoptosis stressors inhibit autophagy and autophagy stimuli inhibit apoptosis; but the actual relationship between autophagy and apoptosis, and their mutual relationship to oxidative stress, is much more subtle and context-dependent (Caballero and Coto-Montes, 2012).

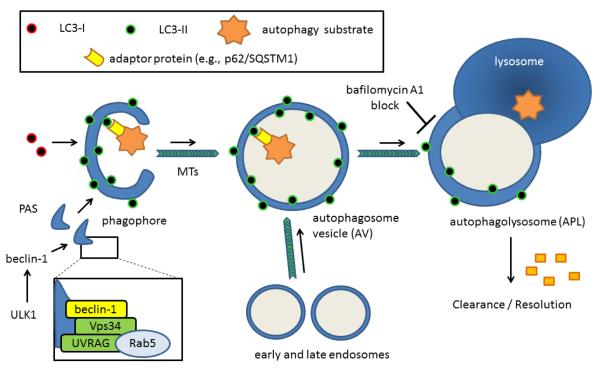

Figure 2. Phagophore initiation, autophagic vesicle maturation and lysosomal fusion / clearance complete the autophagy pathway.

When ULK1 is dis-inhibited from negative regulation by mTORC1, the kinase directly or indirectly triggers assembly of an organizing structure involving beclin-1, VPS34 and other proteins. The immature phagophore structure depends on phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)-conjugated LC3-II or its homologs both for membrane growth and for recruitment of autophagic target structures containing an LIR domain. These LIR-containing adaptors facilitate concentration of predominantly mono-ubiquitinated autophagy substrates within the nascent autophagic vesicle (AV) lumen. The closed autophagic vesicles mature as they move along microtubule tracks and merge with endosomes and lysosomes to yield mature, acidic, autophagolysosomes (APLs) where acidic proteolysis degrades the contents. Such trafficking is likely sensitive to oxidative damage accrued at the microtubules or at the level of oxidatively-sensitive microtubule-associated proteins, including CRMP2, which link cargo packages to motor proteins. Ultimately, the products of this degradation are recycled. Residual LC3 may be de-lipidated (particularly the fraction on the cytoplasmic face) or degraded during the clearance step. Thus, autophagic structural proteins such as p62/SQSTM1 and LC3-II can be useful markers indexing the magnitude of autophagy flux, but can increase either because of increased autophagy flux or from late-stage blockage of AV-APL fusion or APL clearance.

Phagophores elongate by the addition of membrane in a process marked by two distinct ubiquitination processes (Fig. 2). First, an 800 kDa complex forms from the ubiquitin-linked Atg 12 protein; Atg5 and Atg16L1 proteins through the action of the Atg7 (E1 ubiquitin activating enzyme-like) and Atg10 (E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme-like) enzymes. This complex formation is essential for phagophore elongation (Ravikumar et al., 2010) but is released before autophagosomal maturation.

The second ubiquitin-like process involves phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) conjugation to microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (Atg8/MAP1-LC3/LC3) (LC3-I→LC3-II conversion) (Dall’Armi et al., 2013; Klionski et al., 2005; Rogov et al., 2013). In mammals there are six Atg8 homologs: LC3A, LC3B, LC3C, GABARAP, GABARAP-L1, and GABARAP-L2/GATE-16 (Rogov et al., 2013). All Atg8 proteins undergo similar phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) conjugation so hereafter the system is described with respect to LC3 for simplicity with the understanding that variations on the theme exist across different cell types and perhaps at different times. LC3 is synthesized as a precursor that is cleaved by the redox-sensitive cysteine protease Atg4 to form cytosolic LC3-I (Scherz-Shouval et al., 2007; Filomeni et al., 2010; Fernandez and Lopez-Otin, 2015). Indeed, reversible redox regulation of Atg4 may be one of the main points of redox autophagy regulation (discussed further below). LC3-1 and PE are acted upon by Atg7 (E1-like) and Atg3 (E2-like) to form a membrane-localized LC3-II form that persists throughout autophagosome maturation but is ultimately recycled, again largely via Atg4 (Scherz-Shouval et al., 2007; Ravikumar et al., 2010).

The LC3 proteins appear to serve at least two functions. First, they help provide structure to nascent curvilinear phospholipid domains within the phagophore. Second, LC3 proteins bind autophagy “tag” or receptor proteins such as p62/sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1) that contain a short linear LC3-interaction region (LIR). These autophagy receptor proteins preferentially recognize K63-ubiquitinated proteins or organelles being targeted for autophagic digestion via interaction with a C-terminal ubiquitin-binding UBA domain (Rogov et al., 2013). In this way the growing phagophore can engulf even very large structures through a “zipper” mechanism involving sequential association of the target protein, autophagy receptor, and phagophore-localized LC3-II. Mitochondria also can express different autophagy receptors including Atg32 and Atg33 that contain their own LIR interaction domain, facilitating mitochondria-specific macro-autophagy or mitophagy (Rogov et al., 2013). Autophagosomes or autophagic vesicles mature as they are physically moved through cells along microtubules towards lysosomes, and fuse with endosomes during the transit, providing additional materials for ultimate autophagic degradation (Ravikumar et al., 2010).

After lysosomal fusion the autophagy components are turned over and the cycle completes (Fig. 2). LC3-II is de-lipidated and recycled to LC3-I in this step, and LC3 may be degraded more thoroughly (Ravikumar et al., 2010). The delipidation also likely involves Atg4, the same enzyme involved in Atg8→ Atg4 (LC3-I) conversion (Scherz-Shouval et al., 2007; Fernandez and Lopez-Otin, 2015). Surprisingly little is known about the mechanisms of autophagolysosomal clearance and recycling of degraded components, relative to what is known about mechanisms of autophagy initiation and autophagosomal maturation, though beclin-1 may be involved in APL clearance as well as autophagosome formation (Ravikumar et al., 2011).

The above discussion refers to canonical pathways of macro-autophagy that depend on or involve mTOR and beclin-1. Additionally, there may be mTOR and beclin-1 independent pathways involving inositol polyphosphate signaling, cAMP and PLC-dependent systems (Ravikumar et al., 2010). In addition to macro-autophagy, there exist at least two other fundamentally variant autophagy programs termed micro-autophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy. Micro-autophagy involves the direct invagination of lysosomal or endosomal membranes to accept micro-autophagic substrates; and chaperone-mediated autophagy is a pathway by which soluble proteins containing a KFERQ-like pentapetide are recognized by Hsc70 chaperones and translocated across the lysosomal membrane in a Lamp2a-dependent fashion (Rogov et al., 2013). Clearly, autophagy is a very subtle and complex process subject to a great many regulatory inputs.

From this relatively brief discussion it is apparent that there are many points where autophagy can be regulated via redox-sensitive pathways including redox-sensitive transcription or translation of autophagy components; and redox-sensitive modulation of post-translational modifications (PTMs), particularly phosphorylation, which is a common motif of redox signaling (Gabbita et al., 2000). Besides these obvious points of potential redox regulation, it is now recognized that autophagy is controlled by cellular positioning of Rhebs, TSC1/2, mTORCs and lysosomes with respect to one another (Groenewood and Zwartkruis, 2010; Menon et al., 2014; Sancak et al., 2010;). Because protein trafficking is sensitive to both cytoskeletal integrity and redox-regulated PTMs of trafficking proteins (Gellert et al., 2014), this is another important possible point at which oxidative stress could compromise normal autophagy function. The remainder of this review will focus on evidence that autophagy is indeed dysfunctional in a variety of human neuropathologies, and evidence that this disruption may be due, in part, to dys homeostasis of specific redox mechanisms that might control or at least modulate the pace of neural autophagy.

From the preceding discussion one can note many protein markers that could be useful in the assessment of autophagy in experimental systems or clinical samples. However, an important caveat must be noted;autophagy is a pathway wherein intermediate proteins such as LC3-II may increase when the pathway is stimulated from the upstream end, but also can increase if there is a deficit in fusion of autophagic vesicles with the lysosome; or in APL clearance (Klionsky et al., 2012). Hence an increase in LC3-II, for instance, cannot be directly attributed to increased autophagy flux. This has probably caused great confusion and misinterpretation in early correlative studies where autophagy markers were variously associated with either positive or negative clinical outcomes. In order to rigorously determine the meaning of a change in levels of autophagy markers, one must experimentally manipulate cells or animals. One convenient means of doing so, at least in vitro, is to treat cells briefly with low concentrations of bafilomycin-A or other lysosomotropic agent that neutralizes lysosomal pH and prohibits AV-lysosome fusion (Klionsky et al., 2010). If a manipulation increases LC3-II in the presence of the bafilomycin “clamp”, the manipulation probably increases autophagy initiation or stabilizes AVs. Otherwise the manipulation likely impedes AV fusion and APL clearance (Klionsky et al., 2010). Experimental manipulation of whole animal systems is much more difficult but can be done, for instance, through genetic means as will be discussed in particular cases below.

Autophagy related to oxidative stress

It has been argued recently that autophagy acts in concert with classic anti-oxidant defenses such as radical-scavenging small molecules (e.g. tocopherols) and antioxidant enzymes to mitigate damage from sustained, pathophysiological levels of oxidative stress (Giordano et al., 2014). As such, autophagy can be viewed as a mechanism to degrade and recycle protein aggregates that form, in part, through oxidative stress pathways, and to recycle inefficient mitochondria that themselves likely generate too many reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Giordano et al., 2014).

This is an intriguing viewpoint that is amenable to experimental investigation. If autophagy is inhibited in neurobiological systems wherein oxidative stress and protein aggregopathy are observed, the outcome to the system should be detrimental. Likewise, stimulation of autophagy should mitigate biomarkers of oxidative stress and protein pathology. Some recent correlative studies have been published that support this thesis. For instance, classic antioxidants such as polyphenols both reduce oxidative stress and stimulate autophagy in cell cultures (Macedo et al., 2014) but the mechanism behind this phenomenon is unclear and may not relate to polyphenol reduction of oxidative stress. Indeed, at least one study suggests that oxidative stress induces autophagy in retinal ganglion cells (Lin and Kuang, 2014). This might be expected if autophagy is truly a defense against oxidative damage. In another intriguing correlative study, autophagy markers suggested a progressive loss-of-function as oxidative stress and neurodegeneration markers increased in aging Octadon degus, a curious Chilean rodent which has been discovered to exhibit neuropathological features strikingly reminiscent of those seen in human Alzheimer’s disease (Rios et al., 2014). Fewer experimental studies have addressed the relationship of oxidative stress and autophagy in vivo. In one such work, thiamin deficiency (a well-known strategy for inducing oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in vivo) stimulated an increase in autophagy markers Atg5, beclin-1 and LC3-II in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells and rodent thalamic neurons in vivo (Meng et al., 2013). Direct injection of beclin-1 siRNA or PI3K-inhibitor wortmannin exacerbated toxicity associated with thiamin deficiency, whereas stimulating autophagy with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, reduced thiamin deficiency-induced damage (Meng et al., 2013).

The question naturally arises, whether autophagy is a response to oxidative stress or whether oxidative stress is a consequence of impaired autophagy. Past history of research into oxidative stress-related processes would suggest that both may be true in certain contexts and that a dynamic reciprocal relationship may exist. Certainly there is more need for careful experimental studies to shed light upon the relationship of oxidative stress and autophagy in systems that can be manipulated under controlled conditions, and in which proper methods are used to carefully measure autophagy at the levels of initiation, flux and autophagosome clearance.

Redox regulation is a normal feature of autophagy whose disruption can undermine the normally protective function of the Nrf2/Keap1 antioxidant defense system

The preceding discussion alluded to the possible relationship of autophagy to pathophysiological oxidative stress. It is now well-accepted that cellular oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and nitric oxide (●NO) mediate redox signal transduction when produced at low levels or transiently (Gabbita et al., 2000). These redox signaling oxidants affect protein kinase cascades, largely through selective temporary and reversible inactivation of opposing protein phosphatases (Gabbita et al., 2000). This is mediated by transient oxidation of active site thiols to sulfenic acids (or S-nitrosation to S-nitrosothiols), which spontaneously react with ambient glutathione to form mixed disulfides. This signals an enzyme “off” state. A second glutathione equivalent can restore phosphatase activity in the presence of glutaredoxin (Gabbita et al., 2000). It is tempting to speculate that redox signaling levels of oxidant production could affect autophagy directly, perhaps through influencing autophagy-related thiol phsophatases or thiol proteases (Fig. 1), and might even be employed naturally as an autophagy regulatory mechanism. Indeed this appears to be a major phenomenon in the regulation of the protease Atg4 which generates mature Atg8/LC3 and mediates LC3-II turnover (Scherz-Shouval et al., 2007; Fernandez and Lopez-Otin, 2015). As Scherz-Shouval point out, proper function of the Atg8 conversion system requires local reversible control of the Atg4 cysteine proteolytic activity to allow Atg8 maturation (protease “on”) but prevent premature turnover of the PE-conjugated form (protease must be “off”). Atg8 then must be re-activated after lysosome / autosome fusion to facilitate Atg8 recycling. This dynamic Atg4 regulation appears to depend on reversible oxidation of the catalytic Cys81 residue in response to redox signal transduction (Scherz-Shouval et al., 2007).

Work from several other groups substantiates the hypothesis that redox signaling controls normal, healthy autophagy though much more research needs be conducted on this topic, especially in the context of brain cells. For instance a 2014 study by Rahman et al., claims to be the first to present evidence that endogenous ROS production by mitochondria stimulates autophagy in C2C12 myotubes (Rahman et al., 2014). In this work, classic autophagy stimuli such as nutrient deprivation caused increased ROS production which was decreased by the thiol-reducing agent N-acetyl cysteine or the free radical scavenger tempol. These chemical antioxidants, in turn, decreased LC3 lipidation and protein turnover but did not affect mTORC1-mediated ULK1 phosphorylation (Rahman et al., 2014).

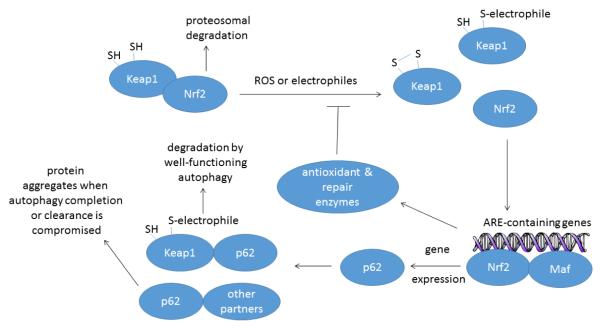

Other studies have found that key autophagy protein expression is redox-regulated, largely through activation of the Nrf2/Keap1 system for antioxidant and electrophilic defense (Fig. 3). Normally, the cysteine-rich Keap1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1) binds and sequesters the Nrf2 (NF-E2-related factor-2) transcription factor in the cytosol. Keap1 brings Nrf2 into close association with the Cullin E3-ligase complex leading to ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation of Nrf2. Oxidation or electrophilic reaction of cysteines in Keap1 frees Nrf2 for translocation to the nucleus where Nrf2 interacts with small Maf transcription factors to increase transcription of genes containing antioxidant response elements (ARE). These targets include cytoprotective phase-II enzymes and antioxidant enzymes such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1) and others (Jaramillo and Zhang 2013; Leinonen et al., 2014). In vascular and hepatic cells at least, p62/sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1) is amongst the suite of Nrf2 regulated proteins whose expression increases upon Nrf2 activation (Ishii et al., 2013; 2004). Therefore, oxidative stress can stimulate subsets of autophagy gene expression, and particularly p62/SQSTM1 expression, via Nrf2 activation. This increased p62 expression is normally balanced by increased p62 turnover when autophagy completes.

Figure 3. Relationship of the Nrf2/Keap1 antioxidant and electrophile response system to autophagy in normal cells and under pathophysiological conditions when autophagy cannot be completed.

Normally, Keap1 sequesters Nrf2 close to the Cullin E3-ligase complex leading to ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation of Nrf2. Upon oxidation or electrophilic modification of sensitive cysteine residues in Keap1, Nrf2 is freed for nuclear translocation where it acts in conjunction with small Maf transcription factors to up-regulate genes containing antioxidant response elements (AREs). Through this process Nrf2 can stimulate expression of genes coding for Keap1 and p62/SQSTM1. p62, in turn, adapts oxidized Keap1 for autophagic degradation allowing rapid recovery of the Nrf2/Keap1 system after oxidative insult. In a situation where AV-APL fusion is compromised or APL clearance is perturbed, however, p62 complexes may accumulate, which could explain the common presence of p62+ and ubiquitin+ aggregates along with high numbers of autophagic vesicle structures in degenerating neurons, such as is observed in Alzheimer’s diseased brain.

When autophagy progression or resolution is blocked, though, the situation changes with negative consequences. Nrf2-stimulated p62 expression is exacerbated through a direct interaction of p62 with Keap1 which sequesters Keap1 and further stabilizes Nrf2 (Lau et al., 2010; Komatsu et al., 2010; Taguchi et al., 2012). Therefore, disruption of autophagy through liver-specific ablation of Atg7 causes liver damage associated with increased p62/SQSTM1 protein and constitutive Nrf2 activation (Taquchi et al., 2012). Liver damage in this mouse can be rescued by deleting Nrf2 or p62 but is exacerbated by deleting Keap1 (Taquchi et al., 2012). Such observations led Riley et al. (2010) to hypothesize that the general accumulation of poly-Ub chains in autophagy-deficient circumstances could be an indirect consequence of activation of Nrf2-dependent stress response pathways. This is a plausible point of view deserving of closer attention.

A related study by Zhao et al., (2013) showed that both ultraviolet radiation (UVA) and UVA-oxidized lipids induced autophagy in keratinocytes. Moreover, UVA-induced formation of p62/SQSTM1+ high-molecular weight protein aggregates was exacerbated in autophagy deficient Atg7-deficient keratinocytes (Zhao et al., 2013). Strikingly, Nrf2 activation was elevated in the Atg7-deficient cells even in the absence of external stimuli (Zhao et al., 2013). From these two investigations it appears clear that the Nrf2 and p62/SQSTM1 positively stimulate one another insofar as Nrf2 increases p62 expression, and p62 indirectly stabilizes Nrf2. Because Nrf2 also upregulates Keap1, p62-dependent autophagy of Keap1 would normally accelerate turnover of electrophilically-modified Keap1 and ensure efficient recovery of the Nrf2/Keap1 system after activation (Taquchi et al., 2012; White et al., 2012). Within a certain realm of physiological stress this might be net cytoprotective; however, blockage of normal autophagy flux can lead to dyshomeostasis of the Nrf2/Keap1/p62 network and cytopathic p62+ aggregates due to impaired autophagic destruction of p62-cargo complexes (White et al., 2012). Such a phenomenon might be related to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), the characteristic intraneuronal inclusion bodies of AD, because NFTs consistently label with antibodies against p62/SQSTM1 and ubiquitin while cytoplasmic p62 is decreased (Salminen et al., 2012).

Thus far, very little research has been performed exploring the Nrf2/Keap1 relationship to autophagy in neurodegenerative disease specifically, though a very recent study found that genetic ablation of Nrf2 worsened amyloid deposition and neuroinflammation in the APP(Swe)/PS1ΔE9 mouse model of AD, concomitant with an increase in intraneural vesicles (Joshi, Johnson and Johnson 2014). Though a more thorough analysis of autophagy remains to be accomplished in transgenic AD models, this data would suggest that the cross-talk between Nrf2/Keap1 and anti-amyloidogenic autophagic pathways in brain is somewhat analogous to the case described in liver and keratinocytes (discussed above).

From this brief discussion it is clear that redox signaling pathways interact in a dynamic fashion with at least some elements of autophagy, particularly at the level of oxidizable cysteine residues of thiol protease-like enzymes (e.g., Atg4) and at the level of p62/SQSTM1 cross-talk with Nrf2/Keap1. However, there are a great many more questions that are either unanswered or still haven’t been clearly asked: At what other points of autophagy regulation might ROS positively or negatively affect autophagy? Does normal physiological production of ROS during redox signal transduction influence autophagy, or does ROS only affect autophagy under pathophysiological conditions? Do interactions between redox systems and autophagy machinery occur in the brain the same way they seem to occur in peripheral tissues, and do the consequences differ in the context of neurodegeneration, brain trauma or brain tumorigenesis?

Evidence for autophagy dysfunction in neurodegenerative pathologies and Alzheimer’s disease particularly: A possible opportunity to develop novel therapeutics for a major unmet medical condition

Autophagy is becoming increasingly associated with diverse pathologies including a wide variety of neurodegenerative diseases, in human subjects and in animal models. The association is generally at the level of correlation between autophagy protein levels and disease and is subject to the caveats noted above pertaining to interpretation of changes in levels of autophagy marker proteins. Amongst the autophagy proteins, LC3-II, beclin-1 and p62/SQSTM1 are the most common markers studied. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a good example of a prevalent, medically unmet pathology where autophagy dysfunction is being increasingly implicated as both an etiological factor and a potential therapy target.

AD has long been recognized as a pathology wherein long-lived protein aggregates (namely amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles) accumulate over years. Oxidatively modified proteins, lipids, and DNA likewise accumulate in AD (Kamat et al., 2009). Neuroinflammatory proliferation of microglia, over-production of inflammatory mediators in the local brain parenchyma, glutamate excitotoxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction are all well-known features of AD brain (Hensley et al., 2010a). The addition of autophagic perturbation to the AD pathobiological rubric arises from electron microscopic observations that autophagic vesicles increase in number, in clinical AD samples and mouse models (Nixon 2011) Detailed studies of AD models by Pickford et al., (2008) revealed that beclin-1 is decreased by a median 35% in mild cognitive impairment (prodromal AD) and up to 70% in frank AD. Similar observations have been made by Rohn and colleagues and therein attributed to increased beclin-1 turnover through caspase-dependent proteolysis (Rohn et al., 2011). Though beclin-1 is not decreased in two different AD mouse models (T41 and J20 amyloid precursor protein (APP)-overexpressing mice), experimental decrease of beclin-1 in these mice by breeding to Becn1+/- animals does increase brain amyloid beta peptide (Aβ) deposition by 2-fold whereas beclin-1 increase via lentiviral transduction, decreases amyloid burden (Pickford et al., 2008). Intriguingly, beclin-1 expression levels predict CD68+ microglial labeling in APP+Becn1+/− mice (Pickford et al., 2008). Perhaps most importantly, APP+Becn1+/− mice suffered age-related loss of neurons in layer II of the entorhinal cortex (Pickford et al., 2008). Normally, APP-overexpressing mice do not suffer frank neurodegeneration, suggesting that the experimental reduction in mouse beclin-1 may have created a more complete pathological presentation than would normally be seen in an AD mouse model (Pickford et al., 2008). Other, recent studies find that beclin-1 is decreased in microglia from AD brain and that decreased beclin-1 impairs microglial phagocytosis through dysfunctional recruitment of retromer to phagosomal membranes, reduced retromer levels, and impaired recycling of phagocytic receptors CD36 and Trem2 (Lucin et al., 2013).

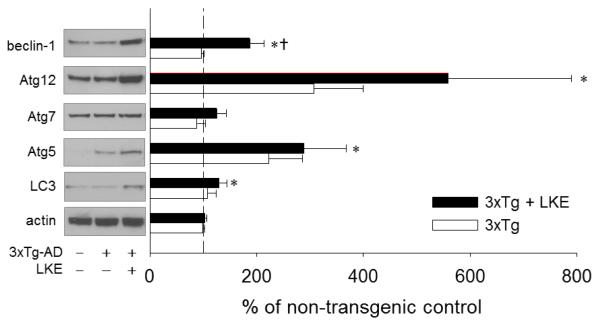

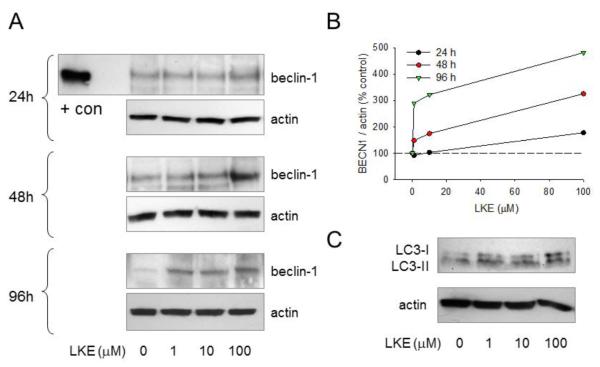

It would be difficult to genetically manipulate autophagy for therapy in an adult human brain, however several studies raise the hope that autophagy might be pharmacologically engaged for therapeutic effect in AD. At least two studies offer strong evidence that rapamycin derivatives can decrease amyloid burden in APP-overexpressing mouse models when administration is begun early enough (Jiang et al., 2014; Majumder et al., 2011). Likely other molecules exist or could be invented that stimulate autophagy through similar or very different mechanisms than rapamycin derivatives. We have published that a brain-penetrating ester form of the natural neural metabolite and antioxidant molecule, lanthionine ketimine (Hensley et al., 2010b, 2010c, 2015) can likewise reduce amyloid and phosphorylated tau and alleviate cognitive deficits in a 3xTg-AD mouse model of AD (Hensley et al., 2013). In an effort to uncover clues as to LKE’s mechanism-of-action, brain cortical lysates archived from the 3xTg-AD mice from the prior published study were probed with panels of antibodies to discrete cell process patterns. A panel of autophagy protein-directed antibodies indicated significant upregulation of multiple autophagy-associated proteins including beclin-1, Atg-12, Atg-5 and LC3 in brains of 3xTg-AD mice that had been treated from 7-15 months with LKE (Fig. 4). In particular, beclin-1 protein was increased by a mean 80% by LKE and LC3 protein was significantly increased though the lysis methods had not been optimized to reliably recover both LC3-I and LC3-II in these samples (Fig. 4). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) revealed no significant change in beclin-1 mRNA in contralateral specimens from the same mouse brains (data not shown) suggesting the protein increase was due to post-translational stabilization. The LKE-treated mice did not differ from controls with respect to weight gain or retention, organ histology, or blood chemistry; and had equal or greater physical capacity as judged by swim speeds (Hensley et al., 2013) belaying any concerns that the upregulation of autophagy markers might be due to nutritional compromise due to adverse drug tolerance. LKE increases beclin-1 protein (but not mRNA) in the brains of 3xTg-AD mice that were chronically treated with this compound (Fig. 4) and also in a variety of cell cultures including SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells (Fig. 5) in which LKE reduces spontaneous amyloid-beta production (Hensley et al., 2013).

Figure 4. The experimental therapeutic LKE stimulates increase in autophagy protein markers in brains of 3xTg-AD mice that had received chronic oral LKE.

Archived brain cortical lysates from a prior study of LKE efficacy in the 3xTg-AD mouse model of AD (detailed experiments and LKE pharmacology in this model previously described in Hensley et al., 2013) were probed with a panel of antibodies against autophagy markers. The dashed line indicates 100% level, mean of nontransgenic (non-Tg) control samples. *P<0.05 relative to age-matched nontransgenic control mice; †P<0.05 relative to 3xTg-AD control mice; N=6 mice / group.

Figure 5. LKE increases beclin-1 in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells, in a time- and dose-dependent fashion.

SH-SY5Y cells were cultured as previously described (Hensley et al., 2013). The antioxidant and neurotrophic molecule LKE was added to cell culture media from a concentrated stock solution (in saline) to achieve final concentrations. Cells were lysed and blotted for beclin-1 (rabbit polyclonal antibody B6186, Sigma-Aldrich) or actin (mouse monoclonal AC-15) after 1-4 days (A,B) or LC3A (Rabbit monoclonal antibody, clone D50G8-XP®, Cell Signaling Technologies) after 4 days (C). LKE increased beclin-1 protein expression in a dose- and time-dependent fashion with a 2-fold increases observed at 1 μM LKE after 5d. The LC3-II lipidation could be observed after overnight treatment in the absence of bafilomycin or several hour’s treatment in the presence of bafilomycin (not shown) suggesting that the beclin-1 effect is independent from, or perhaps a consequence of, a more immediate but persistent LKE effect on autophagy dynamics.

The LKE effect on autophagy is remarkable, particularly because LKE is a cell-penetrating form of a natural mammalian metabolite. The effects of LKE on autophagy and beclin-1 expression are not, however, totally unprecedented. Several natural botanical products including dicatechols, curcumin, resveratrol, paclitaxel and the flavonoid quercetin all have been reported to induce LC3-lipidation in certain cancer cell lines; moreover curcumin increases beclin-1 expression in K562 leukemia cells (Jia et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2012). Unfortunately too little is known about the mechanisms of these natural products to argue for, or against a commonality with LKE; but not all antioxidants induce autophagy, and the magnitude of LKE effect is disproportionate with its modest ability to scavenge peroxides (Hensley et al. 2010c). Thus the LKE effects on autophagy are likely to be mechanistically dissimilar from plant products and likely not due to a simple ROS/RNS scavenging mechanism.

When considering autophagy stimulating molecules as potential therapeutics, one should bear in mind that stimulating autophagy is not always and everywhere, a desirable goal. For instance, as discussed above, a late-stage block in autophagy clearance would force a build-up of potentially neurotoxic protein aggregates due to impaired autophagic destruction of p62-cargo complexes (White et al., 2012). Stimulating autophagy in the initiation phase, upstream from beclin-1 and ULK1, might be counter-indicated in this situation and might worsen disease. Indeed some of the most important questions now revolve around understanding the circumstances that convert beneficial autophagy to detrimental autophagy and identifying the precise level of autophagy dysfunction in particular disease states so that the autophagy malfunction can be addressed at an appropriate, therapeutic point.

A hypothesis linking oxidative damage to microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) with autophagy failure may present a new perspective from which to view AD, motor neuron disease, and other neurodegenerative pathologies

Amongst the proteins known to be oxidatively damaged in AD, cytoskeletal proteins including microtubule-associated adaptor molecules are often cited as particularly vulnerable (Di Domenico et al., 2014; Hensley et al., 1995). The microtubule-associated protein (MAP) CRMP2 (collapsin response mediator protein-2; CRMP2; dihydropyrimidinase-related protein-2 or DPYSL2) is amongst the most heavily carbonylated and hydroxynonenal-modified proteins identified in AD brain and in several murine models of neurodegenerative pathologies including the SOD1G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Perluigi et al., 2009, 2005). CRMP2, like the more frequently discussed AD-associated MAP protein tau, suffers hyperphosphorylation and collects in neurofibrillary tangles (Cole et al., 2007; Gu et al., 2000; Yoshida et al., 1998) and has been hypothesized to deplete AD neurons of functional CRMP2 (Takata et al., 2009; Yoshida et al., 1998). CRMP2 directly and indirectly stabilizes microtubules but also connects cargo proteins and vesicles to kinesin and dynein motors to facilitate intracellular trafficking and axonal stability (Astle et al., 2011; Khanna et al., 2012; Manser et al., 2011; Rahajeng et al., 2010; Takata et al., 2009). As discussed above, subcellular localization of components is an important theme in the regulation of multiple steps of autophagy including mTOR and TSC localization as well as movement of autophagic vesicles (Fig. 2). Thus it is theoretically plausible to speculate that oxidation of CRMP2 or hyperphosphorylation secondary to prolonged oxidative stress, could impair key steps in autophagy, engendering buildup of autophagic vesicles and undigested cargo.

This idea is consistent with published findings that NFTs contain abundant p62 and ubiquitinated proteins (Salminen et al., 2012). Simultaneously, AV accumulation would be expected to effect a backlog in endosomal trafficking and would provide more opportunity for APP to undergo amyloidogenic processing within acidic intracellular vesicles, thus increasing amyloid burden. Indeed, experimental suppression of CRMP2 using shRNA suppresses autophagy flux as indicated by a relative decrease in LC3-II formation during bafilomycin clamp in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells (Hensley et al., 2015; this issue) whereas the autophagy-inducing compound LKE decreases spontaneous Aβ(1-40) release from SH-SY5Y cells (Hensley et al., 2013). While this hypothesis is highly speculative, it offers a novel perspective which links oxidative stress, protein aggregation and autophagy in a way that places the key histopathological features of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in a more downstream role than is currently envisaged by most etiological paradigms. The hypothesis also suggests new targets and processes which might be exploited for therapeutic benefit to alleviate AD-associated autophagy deficits, AD cytopathology and ultimately reduce neurodegeneration.

This hypothesis could be taken yet further, by extrapolation to other neurodegenerative pathologies than AD. Ubiquitinated protein aggregates including p62+ deposits are a common feature of several neurodegenerative disorders including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Mizuno et al., 2006) and other motor neuron diseases. Oxidative stress is a well-documented feature of ALS (Hensley et al., 2006) while there appears to be an imbalance of decreased Nrf2 protein and increased Keap1 in human ALS spinal cord and motor cortex (Sarlette et al. 2008) perhaps indicating an imbalance between autophagic degradation of Keap1 and proteosomal degradation of Nrf2. LKE and rapamycin both have been reported to produce benefits in motor function and longevity of SOD1G93A mice modeling familial ALS (Hensley et al., 2010b; Staats et al., 2013). The rapamycin benefit is only observed in mice lacking mature lymphocytes, however, suggesting that rapamycin-induced immune suppression diminished protective inflammation in SOD1G93A mice and that the optimum drug for central nervous system autophagic dysfunction would need to be one that lacked potent, general immune suppressive activity (Staats et al., 2013).

Conclusions and future directions

This brief review has attempted to argue that relationships exist in the brain between the phenomena of reactive oxygen species biochemistry and autophagy. This is a topic of scientific inquiry which is still very early in its inception, the pursuit of which promises to yield both basic knowledge about the etiology of neurodegeneration and new therapeutic concepts for translational research. Alzheimer’s disease and mouse models of this disease offer excellent examples of cases in which autophagy appears dysfunctional and likely causal to histopathological components including abnormal protein aggregates and neuroinflammation. Autophagy manipulation in AD models, accomplished through molecular biological or therapeutic means, has so far reliably either exacerbated or diminished amyloidogenic aspects of presentation in accord with the hypothesis that a fully functioning macro-autophagy system is healthy and anti-amyloidogenic. Future research might be productively aimed at understanding how redox signal transduction affects discrete levels of autophagy initiation, progression and autophagolysosomal clearance; how dynamic transport of autophagy regulatory machinery affects the process through subcellular localization; and how novel chemical entities or natural products might engage redox-dependent autophagy for therapeutic benefit in preclinical models.

Highlights.

Autophagy is a highly regulated cellular recycling system

Autophagy acts selectively on macromolecular aggregates and whole organelles.

Autophagy dysfunction is a common feature of diverse neurodegenerative pathologies.

Autophagy interacts reciprocally with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS).

Modulating the relationship between ROS and autophagy may be therapeutically useful.

Acknowledgments

Funding and disclosure

This work was supported in part by the University of Toledo Foundation Biomedical Innovation Award (KH); Veterans Administration Merit funding (MHW); a grant from the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA217526; KH); and the National Institutes of Health (NS082283; KH). KH is the inventor on U.S. patent 7,683,055 (other patents pending) covering composition and use of lanthionine ketimine derivatives including lanthionine ketimine-ester (LKE) and holds equity in a company engaged in commercial development of the technology.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AKT

AKT phosphotidylinositol-3-kinase (protein kinase B)

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- APLs

autophagolysosomes

- Atg

autophagy protein

- AVs

autophagic vesicles

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma-2 gene product

- CNS

central nervous system

- CRMP2

collapsin-response mediator protein 2 (dihydropyrimidinase-like protein-2; DPYSL2)

- Keap-1

Kelch-like ECH-related protein-1

- JNK

c-Jun amino terminal kinase

- LanCL1

lanthionine cyclase-like protein-1

- LC3

microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3)

- LK

lanthionine ketimine

- LKE

lanthionine ketimine-ethyl ester

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- mTORC1(2)

mTOR complex-1(2)

- Nrf2

NF-E2-related factor-2

- p70S6K

p70S6 ribosomal protein-directed protein kinase

- p62/SQSTM1

sequestosome-1 protein

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TSC

tuberous sclerosis complex

- Tsc1

tuberous sclerosis complex gene-1(hamartin)

- Tsc2

tuberous sclerosis complex gene-2 (tuberin)

- ULK1

uncoordinated 51-like autophagy-regulating kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Astle MV, Ooms LM, Cole AR, Binge LC, Dyson JM, Layton MJ, Petratos S, Sutherland C, Mitchell CA. Identification of a proline-rich inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase (PIPP)-collapsin response protein 2 (CRMP2) complex that regulates neurite elongation J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:23407–23418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.214247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero B, Coto-Montes A. An insight into the role of autophagy in cell responses in the aging and neurodegenerative brain. Histol. Histopathol. 2012;27:263–275. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole AR, Noble W, van Aalten L, Plattner F, Meimaridou R, Hogan D, Taylor M, LaFrancois J, Gunn-Moore F, Verkhratski A, Oddo S, LaFerla F, Giese KP, Dineley KT, Duff K, Richardson JC, Yan SD, Hanger DP, Allan SM, Sutherland C. Collapsin response mediator protein-2 hyperphosphorylation is an early event in Alzheimer’s disease progression. J. Neurochem. 2007;103:1132–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Armi C, Devereaux KA, Di Paolo G. The role of lipids in the control of autophagy. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:R33–R45. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Domenico F, Pupo G, Tramutola A, Giorgi A, Schinina ME, Coccia R, Head E, Butterfield DA, Perluigi M. Redox proteomics analysis of HNE-modified proteins in Down syndrome brain: Clues for understanding the development of Alzheimer disease. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2014;71:270–280. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AF, Lopez-Otin C. The functional and pathologic relevance of autophagy proteases. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:33–41. doi: 10.1172/JCI73940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filomeni G, Desideri E, Cardaci S, Rotilio G, Ciriolo MR. Under the ROS: Thiol network is the principal suspect for autophagy commitment. Autophagy. 2010;6:999–1005. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.7.12754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbita SP, Robinson KA, Stewart CA, Floyd RA, Hensley K. Redox regulatory mechanisms of cellular signal transduction. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;376:1–13. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher LE, Chan EY. Early signaling events of autophagy. Essays Biochem. 2013;55:1–15. doi: 10.1042/bse0550001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellert M, Hanschmann EM, Lepka K, Berndt C, Lillig CH. Redox regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics during differentiation and de-differentiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014:ii. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.10.030. S0304-4165(14)00367-5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.10.030. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano S, Darley-Usmar V, Zhang J. Autophagy as an essential cellular antioxidant pathway in neurodegenerative disease. Redox Bio. 2014;2:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Hamajima N, Ihara Y. Neurofibrillary tangle-associated collapsing response mediator protein-2 (CRMP2) is highly phosphorylated on Thr-509, Ser-518, and Ser-522. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4267–4275. doi: 10.1021/bi992323h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley K, Hall N, Subramaniam R, Cole P, Harris M, Aksenov M, Aksenova M, Gabbita SP, Wu JF, Carney JM, Lovell M, Markesbery WR, Butterfield DA. Brain regional correspondence between Alzheimer’s disease histopathology and biomarkers of protein oxidation. J. Neurochem. 1995;65:2146–2156. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65052146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley K, Mhatre MC, Mou S, Pye QN, Stewart CA, West MS, Williamson KS. On the relationship of oxidative stress to neuroinflammation: Lessons learned from the G93A-SOD1 mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006;8:2075–2087. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley K. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms, pathologic consequences and potential for therapeutic manipulation. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21:1–14. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley K, Venkova K, Christov A. Emerging biological importance of central nervous system lanthionines. Molecules. 2010;15:5581–5594. doi: 10.3390/molecules15085581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley K, Christov A, Kamat S, Zhang XC, Jackson KW, Snow S, Post J. Proteomic identification of binding partners for the brain metabolite lanthionine ketimine (LK) and documentation of LK effects on microglia and motoneuron cell cultures. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:2979–2988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5247-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley K, Venkova K, Christov A, Johnson M, Eslami P, Gabbitta SP, Harris-White M. A derivative of the brain metabolite lanthionine ketimine improves cognition and diminishes pathology in the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuropath. Exp. Neurol. 2013;72:955–969. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182a74372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley K, Denton TT. Alternative functions of the brain transsulfuration pathway represent an underappreciated aspect of brain redox biochemistry with significant potential for therapeutic manipulation. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2015;78C:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K, Fingar DC. Growing knowledge of the mTOR signaling network. Semin Cell. Dev. Biol. 2014;36C:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Ouyang H, Zhu T, Lindvall C, Wang Y, Zhang X, Yang Q, Bennett C, Harada Y, Stankunas K, Wang CY, He X, MacDougald OA, You M, Williams BO, Guan KL. TSC2 integrates Wnt and energy signals via a coordinated phosphorylation by AMPK and GSK3 to regulate cell growth. Cell. 2006;127:955–968. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Warabi E, Siow RC, Mann GE. Sequestosome 1/p62: A regulator of redox-sensitive voltage-activated potassium channels, arterial remodeling, inflammation, and neurite outgrowth. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2013;65:102–116. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Itoh K, Ruiz E, Leake DS, Unoki H, Yamamoto M, Mann GE. Role of Nrf2 in the regulation of CD36 and stress protein expression in murine macrophages: Activation by oxidatively modified LDL and 4-hydroxynonenal. Circ. Res. 2004;94:609–616. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000119171.44657.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo MC, Zhang DD. The emerging role of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway in cancer. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2179–2191. doi: 10.1101/gad.225680.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell JL, Russell RC, Guan KL. Amino acid signaling upstream of mTOR. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:133–139. doi: 10.1038/nrm3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia YL, Li J, Qin ZH, Liang ZQ. Autophagic and apoptotic mechanisms of curcumin-induced death in K562 cells. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2009;11:918–928. doi: 10.1080/10286020903264077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Yu JT, Zhu XC, Tan MS, Wang HF, Cao L, Zhang QQ, Shi JQ, Gao L, Qin H, Zhang YD, Tan L. Temsilimus promotes autophagic clearance of amyloid-beta and provides protective effects in cellular and animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2014;81:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G, Gan KA, Johnson DA, Johnson JA. Increased Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology in the APP/PS1ΔE9 mouse lacking Nrf2 through modulation of autophagy. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014:ii. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.09.004. S0197-4580(14)00599-5. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.09.004. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat CD, Gadal S, Mhatre MC, Williamson KS, Pye QN, Hensley K. Antioxidants in central nervous system diseases: Preclinical promise and translational challenges. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009;15:473–493. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Wilson SM, Brittain JM, Weimer J, Sultana R, Butterfield DA, Hensley K. Opening Pandora’s jar: A primer on the putative roles of collapsin response mediator protein 2 (CRMP2) in a panoply of neurodegenerative, sensory and motor neuron, and central disorders. Future Neurol. 2012;7:749–771. doi: 10.2217/FNL.12.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Kurokawa H, Waguri S, Taguchi K, Kobayashi A, Ichimura Y, Sou YS, Ueno I, Sakamoto A, Tong KI, Kim M, Nishito Y, Iemura S, Natsume T, Ueno T, Kominami E, Motohashi H, Tanaka K, Yamamoto M. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:213–223. doi: 10.1038/ncb2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau A, Wang XJ, Zhao F, Villeneuve NF, Wu T, Jiang T, Sun Z, White E, Zhang DD. A noncanonical mechanism of Nrf2 activation by autophagy deficiency: Direct interaction between Keap1 and p62. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;30:3275–3285. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00248-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen HM, Kansanen E, Polonen P, Heinaniemi M, Levonen AL. Role of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in cancer. Adv. Cancer. Res. 2014;122:281–320. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420117-0.00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WJ, Kuang HY. Oxidative stress induces autophagy in response to multiple noxious stimuli in retinal ganglion cells. Autophagy. 2014;10:1692–1671. doi: 10.4161/auto.36076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PC, Chan PM, Hall C, Manser E. Collapsin response mediator proteins (CRMPs) are a new class of microtubule-associated protein (MAP) that selectively interacts with assembled microtubules via a taxol-sensitive binding interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:41466–41478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.283580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucin KM, O’Brien CE, Bieri G, Czirr E, Mosher KI, Abbey RJ, Mastroeni DF, Rogers J, Spencer B, Masliah E, Wyss-Coray T. Microglial beclin-1 regulates retromer trafficking and phagocytosis and is impaired in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2013;79:873–886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macedo D, Travares L, McDougall GJ, Vicente MH, Stewart D, Ferreira RB, Tenreiro S, Outeiro TF, Santos CN. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014:ii. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu585. ddu585. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder S, Richardson A, Strong R, Oddo S. Inducing autophagy by rapamycin before, but not after, the formation of plaques and tangles ameliorates cognitive deficits. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon S, Dibble CC, Talbott G, Hoxhaj G, Valvezan AJ, Takahashi H, Cantley LC, Manning BD. Spatial control of the TSC complex integrates insulin and nutrient regulation of mTORC1 at the lysosome. Cell. 2014;156:771–785. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Yong Y, Yang G, Ding H, Fan Z, Tang Y, Luo J, Ke ZJ. Autophagy alleviates neurodegeneration caused by mild impairment of oxidative metabolism. J. Neurochem. 2013;126:805–819. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Y, Amari M, Takatama M, Aizawa H, Mihara B, Okamoto K. Immunoreactivities of p62, an ubiquitin-binding protein, in the spinal anterior horn cells of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2006;249:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA, Yang DS. Autophagy failure in Alzheimer’s disease-locating the primary defect. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011;43:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris EH, Giasson BI. Role of oxidative damage in protein aggregation associated with Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005;7:672–684. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perluigi M, Fai Poon H, Hensley K, Pierce WM, Klein JB, Calabrese V, De Marco C, Butterfield DA. Proteomic analysis of 4-hydroxynonenal-2-nonenal-modified proteins in G93A-SOD1 transgenic mice- A model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Free. Rad. Biol. Med. 2005;38:960–968. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perluigi M, Sultana R, Cenini G, Di Domenico F, Memo M, Pierce WM, Coccia R, Butterfield DA. Redox proteomics identification of 4-hydroxynonenal-modified brain roteins in Alzheimer’s disease: Role of lipid peroxidation in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2009;3:682–693. doi: 10.1002/prca.200800161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickford F, Masliah E, Britschgi M, Lucin K, Marasimhan R, Jaeger PA, Small S, Spencer B, Rockenstein E, Levine B, Wyss-Coray T. The autophagy-related protein beclin shows reduced expression in early Alzheimer disease and regulates myloid beta accumulation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2190–2199. doi: 10.1172/JCI33585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahajeng J, Giridharan SS, Naslavsky N, Caplan S. Collapsin response mediator protein-2 (CRMP2) regulates trafficking by linking endocytic regulatory proteins to dynein motors. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:31918–31922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.166066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M, Mofarrahi M, Kristov AS, Nkengfac B, Haral S, Hussain SN. Reactive oxygen species regulation of autophagy in skeletal muscles. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;209:443–459. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW, Jimenez-Sanchez M, Korolchuk VI, Lichtenberg M, Luo S, Massey DC, Menzies FM, Moreau K, Narayanan U, Renna M, Siddiqi FH, Underwood BR, Winslow AR, Rubinsztein DC. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2010;90:1383–1435. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley BE, Kaiser SE, Shaler TA, Ng AC, Hara T, Hipp MS, Lage K, Xavier RJ, Ryu KY, Taguchi K, Yamamoto M, Tanaka K, Mizushima N, Komatsu M, Kopito RR. Ubiquitin accumulation in autophagy-deficient mice is dependent on the Nrf2-mediated stress response pathway: a potential role for protein aggregation in autophagic substrate selection. J. Cell. Biol. 2010;191:537–552. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201005012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios JA, Cisternas P, Tapia-Rojas C, Rivera D, Braidy N, Zolezzi JM, Godoy JA, Carvajal F,J, Ardiles AO, Bozinovic F, Palacios AG, Sachdev PS, Inestrosa NC. Age progression of neuropathological markers in the brain of the Chilean rodent Octodon degus, a natural model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/bpa.12226. Doi, 10.1111/bpa.12226. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogov V, Totsch V, Johansen T, Kirkin V. Interactions between autophagy receptors and ubiquitin-like proteins form the molecular basis for selective autophagy. Mol. Cell. Rev. 2013;53:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohn TT, Wirawan E, Brown RJ, Harris JR, Masliah E, Vandenabeele P. Depletion of beclin-1 due to proteolytic cleavage by caspases in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011;43:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A, Kaamiranta K, Haapasalo A, Hiltunen M, Soininen H, Alafuzoff I. Emerging role of p62/squestosome-1 in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2012;96:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for itsactivation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarlette A, Krampfl K, Grothe C, Neuhoff NV, Dengler R, Petri S. Nuclear erythroid 2-related factor 2-antioxidative response element signaling pathway in motor cortex and spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2008;67:1055–1062. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31818b4906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Korolchuk VI, Renna M, Imarisio S, Fleming A, Williams A, Garcia-Arencibia M, Rose C, Luo S, Underwood BR, Kroemer G, O’Kane CJ, Rubinstein DC. Complex inhibitory effects of nitric oxide on autophagy. Mol. Cell. 2011;43:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz-Shouval R, Shvets E, Fass E, Shorer H, Gil L, Elazar Z. Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. EMBO J. 2007;26:1749–1760. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staats KA, Hernandez S, Schonefeldt S, Bento-Abreu A, Dooley J, Van Damme P, Liston A, Robberecht W, Van Den Bosch L. Rapamycin increases survival in ALS mice lacking mature lymphocytes. Mol. Neurodegener. 2013;8:31. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-31. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi K, Fujikawa N, Komatsu M, Ishii T, Unno M, Akaike T, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Keap1 degradation by autophagy for the maintenance of redox homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13561–13566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121572109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata K, Kitamura Y, Nakata Y, Matsuoka Y, Tomimoto H, Taniguchi T, Shimohama S. Involvement of WAVE accumulation in A-beta/APP pathology-dependent tangle modification in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;175:17–24. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E. Deconvoluting the context-dependent role for autophagy in cancer. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth M, Juachim J, Tooze SA. Autophagosome formation – The role of ULK1 and beclin1-PI3KC3 complexes in setting the stage. Sem. Cancer Biol. 2008;23:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Watanabe A, Ihara Y. Collapsin response mediator protein-2 is associated with neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:9761–9768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Chen LX, Ouyang L, Cheng Y, Liu B. Plant natural compounds: Targeting pathways of autophagy as anti-cancer therapeutic agents. Cell Prolif. 2012;45:466–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2012.00833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Zhang CF, Rossiter H, Eckhart L, Konig U, Karner S, Mildner M, Bochkov VN, Tschachler E, Gruber F. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2013;133:1629–137. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]