Abstract

The extended rod-like Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP) is comprised of three primary domains: a charged N terminus that binds heparan sulfate proteoglycans, a central NANP repeat domain, and a C terminus containing a thrombospondin-like type I repeat (TSR) domain. Only the last two domains are incorporated in RTS,S, the leading malaria vaccine in phase 3 trials that, to date, protects about 50% of vaccinated children against clinical disease. A seroepidemiological study indicated that the N-terminal domain might improve the efficacy of a new CSP vaccine. Using a panel of CSP-specific monoclonal antibodies, well-characterized recombinant CSPs, label-free quantitative proteomics, and in vitro inhibition of sporozoite invasion, we show that native CSP is N-terminally processed in the mosquito host and undergoes a reversible conformational change to mask some epitopes in the N- and C-terminal domains until the sporozoite interacts with the liver hepatocyte. Our findings show the importance of understanding processing and the biophysical change in conformation, possibly due to a mechanical or molecular signal, and may aid in the development of a new CSP vaccine.

INTRODUCTION

The development of a vaccine to aid in the control of malaria is critical, as Plasmodium falciparum has evolved resistance to all antimalarial drugs deployed so far, including artemisinin (1). The leading malaria vaccine (RTS,S), currently in phase 3 trials, contains a formulated virus-like particle that encompasses the central and carboxyl-terminal domains of the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) fused to the hepatitis B virus surface antigen (2) and protects approximately 30% to 50% of infants or children from clinical disease for a limited duration (3, 4). Naturally derived human antibodies against a portion of the N-terminal region, including region 1, are associated with a reduced risk of disease (5), providing a basis to design new CSP vaccines. This N-terminal region of the CSP is absent from RTS,S.

The importance of understanding protein structure because of its impact on the induction of broadly neutralizing antibodies and subsequent vaccine design continues to be revealed in the HIV arena (6, 7). In malaria, the importance of protein conformation for the induction of neutralizing antibodies was recently shown in vivo for an orthologue of the leading asexual-stage malaria vaccine antigen apical membrane antigen-1 (AMA-1). Only a recombinant AMA-1 forming a stable complex with a constrained synthetic rhoptry neck protein-2 peptide induced protective antibodies in vivo against a lethal blood-stage challenge malaria parasite infection (8). When developing a novel CSP vaccine, these more recent developments need to be considered with regard to the potential for changes within the CSP, such as through in vivo processing or conformational changes (9, 10) in a protein with a known extended rod-like structure (11), that could mask the adhesion domains located at the N- and C-terminal domains (9).

To address these questions, a panel of CSP-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against the N-terminal region of the CSP and two well-characterized recombinant forms of the P. falciparum NF54 allele of CSP with distinctive amino termini was developed and used to characterize native CSP in midgut, salivary gland, and saliva sporozoites. We report here that P. falciparum CSP is processed in the mosquito host, and similar to what has been shown in the rodent, malaria parasites may undergo a reversible conformational change, based on epitope recognition of live sporozoites and inhibition of sporozoite invasion (ISI) in vitro. Our findings may aid in the design of a new CSP vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

All studies with animals used for this project were approved by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Directorate of Intramural Research (DIR), Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol ASP LMIV 1E), at the National Institutes of Health, which is AAALAC accredited and Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare assured. The NIAID DIR Animal Care and Use Program acknowledges and accepts responsibility for the care and use of animals involved in activities covered by NIH Intramural Research Program assurance number A4149-01.

Cloning and overexpression of recombinant CSPs.

The amino acid sequence of Plasmodium falciparum CSP (PfCSP; Array Express accession number 3D7, GenBank accession number XP_001351122) was used to generate a codon-optimized synthetic gene for expression in Escherichia coli (GenBank accession number KT363725). The construct, corresponding to amino acids Gly27 to Ser384 of the full-length CSP, was subcloned into the E. coli/pET-24a(+) expression vector downstream of the T7 promoter using the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. The gene sequence was verified prior to the plasmid being transformed into E. coli T7 Express cells. As with the E. coli expression of CSP (EcCSP), the amino acid sequence of PfCSP (Array Express accession number 3D7, GenBank accession number XP_001351122) was used to produce a Pichia pastoris codon-optimized synthetic gene for expression of CSP in P. pastoris (PpCSP) (GenBank accession number KT363726). A gene corresponding to amino acids Glu74 to Ser383, designed such that the mature secreted CSP contains no heterologous amino acids, was cloned into the XhoI and XbaI sites of the Pichia expression vector pPICZαA under the control of the methanol-inducible AOX1 promoter. The gene sequence was verified before linearization of the plasmid with SacI and transformation into P. pastoris X33 cells. Transformants secreting soluble CSP were identified by colony blot analysis, expression was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, and the best-expressing clones were selected for optimization in 5-liter bioreactors.

Production and characterization of recombinant CSPs.

The two recombinant forms of EcCSP and PpCSP were fermented in 5-liter bioreactors, purified using standard column chromatography, and fully biochemically and biophysically characterized as reported previously (11) and as detailed in the supplemental material.

Production and characterization of hybridomas.

Hybridomas were prepared by Precision Antibody (Columbia, MD) by immunizing mice with the T5305 peptide synthesized by Bio-Synthesis (Lewisville, TX) and conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) using a nonnative carboxyl-terminal cysteine. The hybridomas selected for development were screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) against peptides T5305 and T5409 conjugated to bovine serum albumin (BSA), EcCSP, or PpCSP, Western blotting using alkaline phosphatase-labeled secondary antibodies per the manufacturer's suggestions (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD), and immunofluorescence assay (IFA) on cold methanol-fixed salivary gland sporozoites.

ELISA to characterize MAbs.

The standard ELISA has been described elsewhere (12). Briefly, recombinant CSPs and peptides were coated onto polystyrene plates overnight. Triplicate dilutions of MAbs were incubated on the plates, and binding was detected with alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibodies, followed by incubation with the substrate. After 20 min of incubation with the substrate, the plates were read in a microplate reader to obtain optical density values.

Generation of midgut sporozoites.

Midgut oocyst sporozoites were isolated from Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes infected with the P. falciparum NF54 strain. Briefly, midguts from infected mosquitoes were dissected 10 to 11 days after P. falciparum infection. Pools of 30 midguts were collected and placed in an ice-cold glass microhomogenizer containing 50 μl of RPMI medium with 1% BSA, 1× complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and 15 μM E-64 protease inhibitor. Midguts were homogenized with 8 to 10 strokes, 250 μl of the homogenization medium was added to wash the pestle, and the whole midgut homogenate was filtered using glass wool as previously described (13). Pellets containing sporozoites were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage at −70°C or resuspended in medium for live immunostaining.

Salivary gland sporozoite purification and flow cytometry.

The method used for purification of salivary gland sporozoites was based on a published method (14). The salivary glands of A. stephensi mosquitoes infected with P. falciparum NF54 were dissected into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% BSA in a volume of 1 ml. This mixture was overlaid onto 3 ml of a 17% (wt/vol) iodinated benzoic acid (Accudenz) solution in a 15-ml tube, and the tube was centrifuged at 2,500 × g at 25°C for 20 min with no brake. The interface was removed and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 3 min. The supernatant was removed, and the sporozoite pellet was suspended in PBS–1% BSA for staining. The mouse MAbs indicated in the Results were used at 0.5 μg/ml to label 5 ×105 sporozoites in a volume of 100 μl. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin secondary antibody was used at 0.2 μg/ml. Samples were acquired on a BD LSR II flow cytometer (100,000 events per sample), and the data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Saliva sporozoites.

Sporozoites secreted into saliva were collected from A. stephensi mosquitoes 15 to 16 days after infection with P. falciparum. Groups of 50 to 60 mosquitoes were allowed to probe and salivate on glass feeders containing 300 μl of RPMI medium with 10% human serum. The glass feeders had stretched Parafilm as a membrane and were maintained at 38°C with a water jacket. Mosquito probing was interrupted after 10 to 15 s by removing the mosquito container and immediately resumed. The interrupted probing was maintained for 30 min with 3 groups of mosquitoes in 3 feeders. The medium containing the saliva was pooled, transferred to an ice-cold Eppendorf tube, and received 1× complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 15 μM E-64 protease inhibitor (13).

Quantitative analysis of native CSP by infrared fluorescence Western blotting.

Lysates of the sporozoites from the salivary glands or midguts were loaded at an approximate concentration of 5 × 105 to 1 × 106 sporozoites per lane on Mini-Protean TGX, 4 to 20% or Criterion XT bis-Tris, 10% precast gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. As a reference, 62.5 ng of EcCSP and PpCSP was independently loaded in separate lanes and, optionally, as a mix on a third lane. After electrophoretic separation, the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with Tris-buffered saline (TBS), 3% skim milk, pH 8.0. All washes and antibody dilutions were performed in TBS with 0.5% Tween 20, pH 8.0. After the membranes were blocked, they were incubated with different anti-CSP MAbs (MAb 3A1, 3B4, 4B3, and/or 1G2) at a concentration of 20 μg/ml for 1 h. A second antibody incubation by using polyclonal rabbit anti-PpCSP antiserum at a dilution of 1:5,000 followed for an additional hour. Bound antibodies were made detectable by incubation with a mix of IRDye 680RD goat anti-rabbit and IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin secondary antibodies (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) at a dilution of 1:10,000 each for 30 min. Detection was achieved by simultaneous membrane scanning at 700 and 800 nm in an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE).

Quantitative analysis of native CSP by LC/MSE.

A quantitative analysis was done as described earlier (15). Briefly, recombinant EcCSP and 10 million sporozoites were diluted with/suspended in 100 μl buffer consisting of a final concentration of 50 mM NH4HCO3 and 0.2% RapiGest SF surfactant (catalog number p/n 186001861; Waters). Both samples were incubated in ice for 30 min, followed by incubation at 80°C for 10 min. Samples were digested by sequencing-grade trypsin and incubated at 37°C overnight. Before the digestion, 10 μl of 100 mM dithiothreitol was added at 60°C for 30 min to reduce the disulfide bonds, and then free cysteine residues were alkylated with 10 μl of 300 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. Trifluoroacetic acid (0.05%, vol/vol) was used to quench the enzymatic reaction and degrade the RapiGest SF surfactant. The pH of the samples was adjusted to 10 by adding 10 μl of 1 N NH4OH for effective trapping on the first-dimension column. Samples were spiked with alcohol dehydrogenase before loading the two-dimensional NanoAcquity ultraperformance liquid chromatograph for load normalization. Data acquisition was done in positive ion mode using a NanoLockSpray electrospray ion source controlled by MassLynx (version 4.1) software. Digested samples were loaded on the first-dimension trap column (300 μm by 50 mm; particle size, 5 μm; XBridge BEH130 C18) at pH 10 and eluted to a second-dimension trap column (180 μm by 20 mm; particle size, 5 μm; Symmetry C18) with 50% acetonitrile and 50% 20 mM ammonium formate at pH 10 (mobile phases for the first-dimension pump) at a flow rate of 2 μl/min. Peptides eluted from the first dimension were then diluted and acidified with 0.1% formic acid (FA) in water at a flow rate of 20 μl/min, prior to trapping onto the second-dimension trap column. The peptides were separated on the second-dimension analytical column (75 μm by 100 mm; particle size, 1.8 μm; HSS T3) with a 90-min gradient from 3 to 60% mobile phase B (0.1% FA in acetonitrile). An alternating low-collision-energy (6-V) and elevated-collision-energy (ramping from 15 to 35 V) acquisition was used to acquire peptide precursor (MS) and fragmentation (MSE) data. Data were acquired at a scan rate of 1 spectrum per second. The capillary voltage was 3.4 kV, the source temperature was 100°C, and the cone voltage was 41 V. Sampling of the lock spray channel was performed every 30 s. Spectra were recorded from m/z 50 to 1,990. Samples were run in quintuplicate.

The LC/MSE data were processed and searched using a TransOmics platform. (MSE is alternate scanning liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry [LC/MS], where the alternating full scan modes are of low energy and elevated energy, performed in such a manner as to capture the chromatographic profiles of precursor and product ions.) Peptide/protein identifications were obtained by searching the FASTA database for sequences that match the PfCSP and alcohol dehydrogenase protein sequences. Peak picking, alignment, and advanced statistical tools, including analysis of variance, power analysis, and q-value determination, were used to process the data using the TransOmics platform. Due to the parallel mode of data acquisition, the tryptic peptides that are of sufficient intensities produce aligned product ion fragmentation data that can be used for structural identification of that peptide and its corresponding protein.

Analysis of live and fixed sporozoites by IFA.

Live sporozoites from salivary glands or mosquito midguts were supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) to reach a final concentration of 10% and independently incubated with different anti-CSP MAbs (MAbs 3A1, 3B4, 3H10, 4B3, and 1G2) and with an anti-Pfs25 MAb (MAb 4B7) as an internal negative control (data not shown) at a final concentration of 25 μg/ml for 1 h on ice. Subsequent sporozoite washes as well as all antibody dilutions were performed in PBS–10% FBS. After two washes, the pelletized sporozoites were resuspended in ∼10 μl of PBS–10% FBS and applied on a multiwell glass slide, and the cell suspension was allowed to air dry on the slide at room temperature for 10 min. The slide was then sealed in the presence of desiccant and stored at −70°C until processing. Upon processing, the slides were quickly fixed with methanol and incubated with a polyclonal rabbit antiserum against PpCSP at a dilution of 1:500 for 30 min. All antibody incubations were separated by extensive washing with PBS. Finally, the slides were incubated with a mix of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) at 20 μg/ml each for 30 min. After washing with PBS, the samples were mounted under coverslips using Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for fluorescence.

A slight modification of this procedure involved slide incubation with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) for 30 min after the slide was thawed from −70°C. The slide was then incubated with 50 μg/ml of anti-CSP MAb 4B3 conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 for 30 min before being mounted with Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI.

In the case of fixed sporozoites, the salivary gland or midgut samples were washed in cold PBS–10% FBS, and the pelletized sporozoites were diluted in a minimal volume so that ∼5 μl of this suspension was applied to multiwell glass slides, air dried, stored, and processed as previously described (11).

All processed and mounted slides were kept under dark conditions at 4°C until images could be acquired by fluorescence microscopy (with an Olympus BX51 fluorescence and differential inference contrast microscope equipped with an Olympus DP72 microscope digital camera; Olympus, Melville, NY) and/or by confocal microscopy as previously reported (11).

Sporozoite motility assay.

Sporozoites were collected from the salivary glands of A. stephensi mosquitoes 15 to 16 days after infection with P. falciparum. Individual chambers from a multichamber slide were incubated with 10 μg/ml IgG using MAbs 3A1, 3B4, 1G2, and 4B3, washed with PBS, and then incubated with 50,000 sporozoites in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium–3% BSA for 1 h. The unbound sporozoites were removed, and the slides were fixed and blocked essentially as described previously (16, 17). Sporozoites and CSP trails were detected with polyclonal rabbit anti-PpCSP antiserum, which was detected with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR). Some sporozoites were incubated with 1 μM cytochalasin D prior to incubation on MAb 1G2 to control for sporozoite motility.

ISI.

In vitro ISI studies were performed using HepG2 cells as previously described (10, 18). Briefly, sporozoites were plated on cells for 1 h at 37°C. After incubation with sporozoites, the cells were washed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and sporozoites were stained with MAb 2A10 (which is specific for P. falciparum), followed by anti-mouse Ig conjugated to rhodamine. The cells were then permeabilized with cold methanol and stained again with MAb 2A10, followed by anti-mouse Ig conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). All sporozoites were FITC positive, whereas only extracellular sporozoites stained with rhodamine.

AFM.

Biological imaging of the protein products was carried out by atomic force microscopy (AFM) under a range of conditions basically as previously described (11). Briefly, we used gentle-tapping-mode AFM, mostly with a PicoForce Multimode AFM (Bruker, CA) consisting of a Nanoscope V controller, a type E scanner head, and a sharpened TESP-SS (Bruker, CA) or similar AFM cantilever. For PpCSP visualization, suitable protein attachment was achieved by 5 min of incubation of 5 μl of a 400-ng/ml PpCSP solution in PBS, pH 7.4, on freshly peeled mica substrates, followed by rinsing with ∼1 ml of deionized water and complete drying under an inert gas flow. The sample was then sealed into the AFM instrument compartment, which had been dehumidified by Drierite particles. AFM images were evaluated within the Nanoscope software (version 7.3-8.15; Bruker, CA) and exported to ImageJ (version 1.47v; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and Microsoft Excel (version 2010; Microsoft, WA) software for further analyses and display.

Mouse and rabbit immunizations.

All procedures with small animals performed at the National Institutes of Health were in compliance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Groups of 5 female C57BL/6 mice 6 to 8 weeks of age were immunized intramuscularly with 0.05 ml of a formulation containing 5 μg recombinant CSPs in glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant stable emulsion on days 0 and 21. Sera and spleens were harvested on day 35. In addition, female BALB/c mice were immunized subcutaneously thrice at 14-day intervals with 20 μg synthetic T9832 peptide (29-mer from amino acids 39 through 68; Research Technology Branch, NIH, Rockville, MD) amino-terminally conjugated through a nonnative cysteine to maleimide-activated KLH (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) formulated in Freund's complete adjuvant for priming and Freund's incomplete adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) for boosting. New Zealand White rabbits were immunized thrice (on days 0, 28, and 56) with 50 μg of purified PpCSP formulated in ISA 720 VG adjuvant (Seppic, Inc.) administered subcutaneously. Mouse and rabbit sera were collected 2 to 4 weeks following the final immunizations and used at dilutions of 1/200 and 1/500, respectively.

Isolation of lymphocytes and antigen stimulation.

Single-cell suspensions from spleens were obtained by pressing tissue through 70-μm-mesh-size mesh filters and rinsing with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS). Cells were centrifuged, and erythrocytes were lysed with ammonium chloride-potassium lysing buffer. Cells were washed twice with HBSS and suspended in complete medium (Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium, 10% FBS, glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, HEPES). For antigen-specific recall responses, 1 × 106 cells were placed into 96-well round-bottom tissue culture plates and stimulated with 1 μM CSP for 2 h, followed by the addition of 10 μg/ml brefeldin A for 12 to 16 h at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Intracellular cytokine staining.

The following fluorochrome-antibody combinations were used: allophycocyanin (APC)-Cy7-CD3ε (clone 145-2C11; BD Biosciences), V500-CD4 (clone RM4-5; BD Biosciences), BV650-CD8α (clone 53-6.7; Biolegend); APC-gamma interferon (IFN-γ; clone XMG1.2; BD Biociences), phycoerythrin–interleukin-2 (IL-2; clone JES6-5H4; BD Biosciences), and FITC-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α; clone MP6-XT22; BioLegend). Cells were surfaced stained, followed by fixation/permeabilization and cytokine staining in the presence of permeabilization buffer using a BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit following the manufacturer's directions. Samples were acquired on a BD LSR II flow cytometer and analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization and immunogenicity of two recombinant forms of CSP.

To evaluate the benefit of including different portions of the N terminus in a vaccine, we produced two recombinant forms of the P. falciparum NF54 allele of CSP using Escherichia coli and Pichia pastoris expression systems (Fig. 1A). The recombinant proteins (EcCSP and PpCSP, respectively) were characterized (see Fig. S1A to H in the supplemental material), and mice were immunized with both antigens formulated as monomeric proteins in an oil-in-water stable emulsion with glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant, a synthetic Toll-like receptor 4 agonist (19). EcCSP was more immunogenic in mice than PpCSP for both antibody responses (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material) and cellular responses (P < 0.05), as determined for CD4+ T cell responses measuring IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α cytokine responses (see Fig. S2B to D in the supplemental material). These immunological differences could be due to the cleavage of a portion of the N-terminal domain that contains an epitope(s) (Fig. 1B) for CD4+ T cells (see Fig. S2D in the supplemental material). These differences in immunogenicity between EcCSP and PpCSP are in agreement with the findings presented in a previous report on CSP immunogenicity (20).

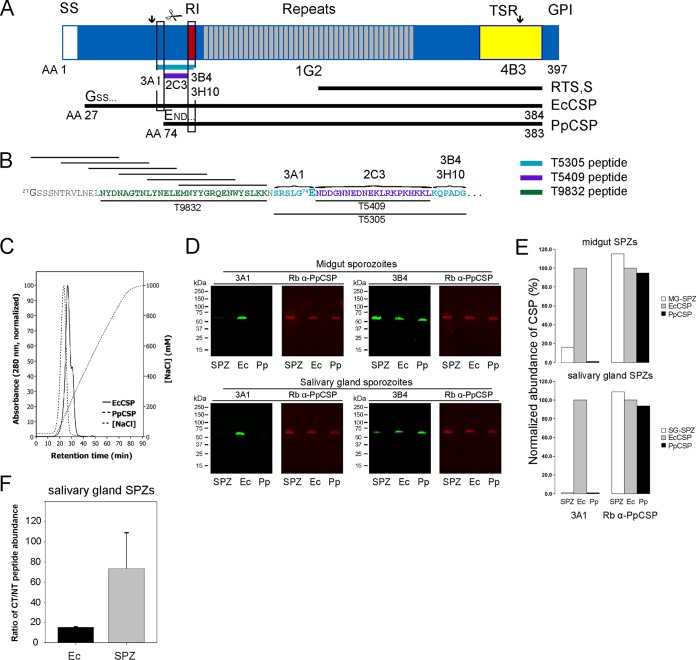

FIG 1.

Analysis of native CSP processing in mosquitoes. (A) Schematic of native CSP and amino acid boundaries for two recombinant CSPs produced in Escherichia coli (Ec) or Pichia pastoris (Pp) along with the epitope mapping of a panel of four N-terminus-specific MAbs (MAbs 3A1, 2C3, 3B4, and 3H10) and two MAbs directed to the NANP repeat region (MAb 1G2) and the TSR region (4B3). Scissors, the location of N-terminal processing; AA numbers, amino acid positions referenced to the amino acid sequence of CSP of P. falciparum NF54 (GenBank accession number P19597); RI, region 1; TSR, thrombospondin-like type I repeat; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor; GSS corresponds to the EcCSP N-terminal amino acid sequence, while END corresponds to the PpCSP N-terminal amino acid sequence. (B) The N-terminal amino acid sequences of EcCSP and PpCSP in which the epitopes of the panel of four MAbs are mapped on synthetic peptides T5305 and T5409 and a series of overlapping 15-mers that were used in T-helper-cell studies. T9832 represents a synthetic amino-terminal circumsporozoite peptide used to generate mouse antiserum. (C) Binding and elution of EcCSP and PpCSP to heparin by column chromatography. (D) Quantitative Western blots of midgut or salivary gland sporozoite (SPZ) lysates (prepared from sporozoites collected on day 10 or day 23 postinfection, respectively) with MAb 3A1 or 3B4 and rabbit (Rb) anti-PpCSP-specific antiserum detected with species-specific secondary antibodies. (E) Fluorescence intensity of native CSP detected by MAb 3A1 or polyclonal rabbit anti-PpCSP in comparison with that of recombinant EcCSP, used for normalization in each respective blot. (Top) Analysis of midgut (MG) sporozoites; (bottom) analysis of salivary gland (SG) sporozoites. (F) Ratio of the abundance of two prototypic C-terminal (CT) and N-terminal (NT) peptides identified in EcCSP or native CSP derived from a salivary gland sporozoite lysate (arrows in panel A). Label-free quantitation was performed by LC/MSE; error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

Native CSP interacts with heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the surface of hepatocytes during the invasion process (18, 21, 22), but the precise region mediating binding has not been defined. We tested whether heparin binding by PpCSP, in which the N terminus of the native CSP protein is deleted to E74, and EcCSP, which has the near full CSP protein sequence, was affected and determined that both EcCSP and PpCSP bound heparin, but EcCSP had a slightly higher binding affinity, as assessed by the increased NaCl concentration required for elution (Fig. 1C). Heparin binding is attributed to the N terminus, since the thrombospondin-like type I repeat (TSR)-containing domain alone does not bind heparin (23). Further, antibodies generated against a synthetic peptide present in the N-terminal domain inhibit sporozoite invasion of hepatocytes in vitro (24), and a synthetic peptide corresponding to L86 to G100 blocks salivary gland invasion (25), indicating the biological importance of the N-terminal domain.

Processing of the native N-terminal region of CSP in mosquitoes.

We generated a panel of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against a synthetic peptide (peptide T5305; Fig. 1B) encompassing the region associated with clinical protection to investigate the processing of CSP during sporozoite maturation in the mosquito vector Anopheles gambiae. Four MAbs were selected and mapped to specific regions upstream (MAb 3A1) or downstream (MAbs 2C3, 3B4, and 3H10) of the N terminus of PpCSP (Fig. 1A and B; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The two MAbs 3B4 and 3H10 mapped to region 1, as determined by a combination of Western blotting and ELISA (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Two other MAbs used here, 1G2 and 4B3, were previously reported (11) to recognize the NANP repeat region and the TSR domain, respectively.

Western blot analyses revealed that MAb 3A1 reacted to a limited extent with native CSP from midgut sporozoite lysates but did not react with salivary gland sporozoite lysates prepared in the presence of protease inhibitors (Fig. 1D, top and bottom left), while MAbs 3B4 (Fig. 1D, top right), 2C3, 1G2, and 4B3 (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material) recognized native CSP in all samples. The presence of equivalent amounts of native CSP in all samples was confirmed using a rabbit anti-PpCSP antiserum (Fig. 1D; see also Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material). Similar results were obtained from two additional independent Western blot analyses (data not shown). Furthermore, a Western blot analysis using salivary gland sporozoite lysates with an antiserum generated against a synthetic N-terminal circumsporozoite peptide (peptide T9832; Fig. 1B) showed no recognition of native CSP (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). When run on a medium-format 10% gel transferred to nitrocellulose, CSP from salivary gland sporozoite lysates collected in the presence of protease inhibitors revealed three bands when probed with MAb 2A10, which is specific for the repeat region (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). This observation is in agreement with findings previously presented in the literature demonstrating that CSP from P. falciparum sporozoites detected with repeat-specific antibodies, including those metabolically labeled, migrates as 2 to 3 bands by SDS-PAGE (26–28). When a medium-format blot was probed with MAb 3B4, only the slowest-migrating band was recognized (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material), and this band appears to have mobility similar to that of the band recognized by MAb 3B4 in alternative SDS-PAGE formats (see Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material). If protease inhibitors are not included in the lysates, native CSP is cleaved in vitro, resulting in a smaller product(s), as described above (see Fig. S4B and C in the supplemental material), and in some cases a complete loss of reactivity with MAb 3B4, indicating cleavage downstream of region 1 (see Fig. S4C in the supplemental material). The weak band detected by MAb 3A1 in the sporozoite lysates was quantitated, and the fluorescence signal was expressed as a percentage of the EcCSP fluorescence signal (Fig. 1E). These data indicate that the N-terminal MAb 3A1-specific epitope has been cleaved or masked due to folding, although this is less likely in the presence of SDS in about 84% of native CSP on the surface of midgut sporozoites and nearly 100% of native CSP for parasites collected from salivary glands.

Proteolytic cleavage of native CSP in salivary gland sporozoites was evaluated using a label-free quantitative proteomic approach, LC/MSE (29). Salivary gland sporozoites and EcCSP were subjected to tryptic digestion, and the abundance of two intact tryptic peptides from the C- and N-terminal ends (see the arrows in Fig. 1A and Fig. S7 in the supplemental material) was determined in each sample. The abundance or signal intensity of each peptide depends on its chemical nature, but the ratio of the signal from the C-terminal and N-terminal peptides for a full-length protein can be calculated using EcCSP as a reference. The average ratio of C-terminal peptides/N-terminal peptides for EcCSP was 15.2, while the ratio of the C- and N-terminal peptides for salivary gland sporozoites was significantly higher at 73.6, which indicates a nearly 5-fold reduction in the amount of the N-terminal peptide in salivary gland sporozoites compared with that in EcCSP (Fig. 1F), indicating that most native CSP in salivary gland sporozoites is cleaved. Finally, the presence of the epitope target for MAb 3A1 was further investigated by IFA. When fixed, membrane-permeabilized, salivary gland sporozoites were costained with MAb 3A1 and rabbit anti-PpCSP antiserum (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material), only 0.5% of parasites detected by the rabbit anti-PpCSP antiserum were also recognized by MAb 3A1. Using a similar format on fixed salivary gland sporozoites, no staining was observed using antiserum to mouse N-terminal circumsporozoite peptide (T9832) (data not shown). The boundary for the amino terminus of PpCSP was determined empirically by failure to express a full-length CSP in P. pastoris. During fermentation of the full-length PpCSP, the secreted form contained an N-terminal end similar to that in our current construct (data not shown). Interestingly, this apparent cleavage site in the P. pastoris CSP is in proximity to a putative native CSP Plasmodium export element domain (R70SLGE) (30), suggesting that it may be naturally cleaved and, furthermore, may reflect the native processed N-terminal end of CSP. Taken altogether, these results provide compelling evidence that the N-terminal region of CSP is cleaved as sporozoites mature in the mosquito. It is worth noting that proteolytic processing has been suggested for Plasmodium vivax CSP (31), and protein processing has been described for other asexual-stage malaria parasite proteins (32–34); in particular, P. falciparum AMA-1 processing is required for the redistribution of AMA-1 to the merozoite surface (35).

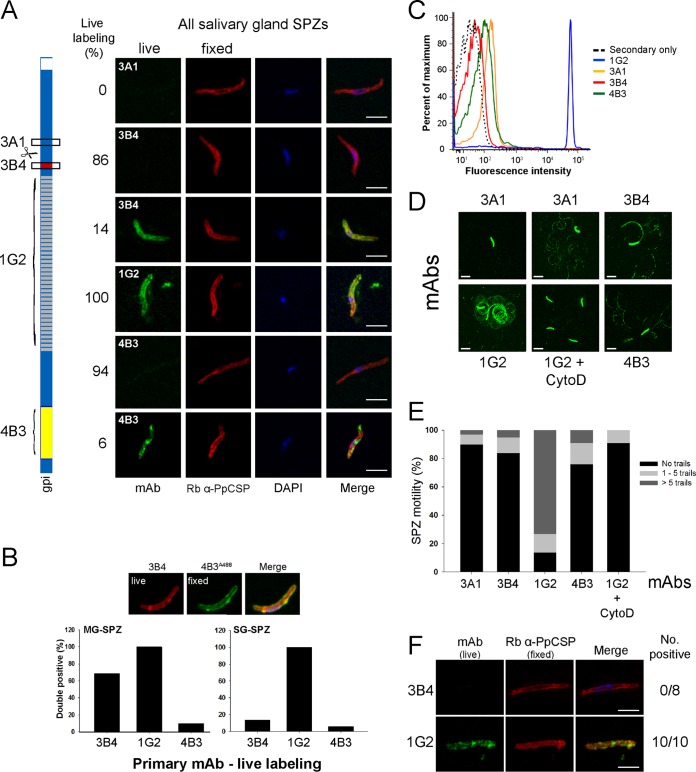

Changes in epitope availability to the CSP-specific MAb panel during sporozoite development.

The complete panel of MAbs was used to investigate the availability of different epitopes of native CSP on sporozoites collected from the midgut or salivary glands in unfixed samples (live IFA labeling). The region 1-specific MAb 3B4 reacted with about 69% of the midgut sporozoites and 14% of the salivary gland sporozoites (Fig. 2A and B, respectively; see also Fig. S9 in the supplemental material). The NANP repeat-specific MAb 1G2 reacted well with both midgut and salivary gland sporozoites, while recognition of the TSR domain by MAb 4B3 was limited overall (Fig. 2A and B; see also Fig. S9 in the supplemental material). We were unable to observe MAb 3A1 reactivity with salivary gland sporozoites (Fig. 2A). The presence of CSP on the sporozoite surface was confirmed by counterstaining of the parasites with either a rabbit anti-PpCSP antiserum (Fig. 2A; see also Fig. S9 in the supplemental material) or MAb 4B3 coupled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Fig. 2B, top) after the samples were fixed and denatured.

FIG 2.

Conformation of the CSP changes during migration from the midgut to the salivary glands. (A) Live IFA with a CSP-specific MAb panel (green) and percent reactivity using salivary gland sporozoites subsequently counterstained after fixation with rabbit anti-PpCSP-specific serum (red). (B) Percentage of live sporozoites recognized by MAb 3B4, 1G2, or 4B3. (Top) After fixation, the sporozoites were counterstained with MAb 4B3 coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 (4B3488); (bottom left) midgut sporozoites (MG-SPZ); (bottom right) salivary gland sporozoites (SG-SPZ). (C) Flow cytometry analysis of live salivary gland sporozoites evaluating surface staining by the CSP-specific MAb panel. (D) Examples of the various patterns of trails detected by the CSP-specific MAbs. (E) The trails shown in panel D were quantitated by scoring the presence of a sporozoite in association with the proximal number of trails (0, 1 to 5, and >5). The percentage of each classification is shown in the stacked bar plot. (F) Live saliva sporozoites collected from feeding mosquitoes showing a lack of surface reactivity with MAb 3B4 but surface reactivity with MAb 1G2. Saliva sporozoites were counterstained with rabbit anti-PpCSP-specific serum. The actual numbers of sporozoites used for the denominator in panel E were 29 for MAb 3A1, 44 for MAb 3B4, 138 for MAb 1G2, 33 for MAb 4B3, and 110 for MAb 1G2 plus cytochalasin D (CytoD). Bars, 5 μm (A and F), 10 μm, and 15 μm (the panel labeled MAb 1G2 + CytoD in panel D).

Interestingly, the proportion of midgut versus salivary gland sporozoites that reacted with MAb 3B4 (69% versus 14%, respectively) indicates that CSP undergoes a conformational change in the salivary gland that results in the MAb 3B4- and the MAb 2C3-specific epitopes (data not shown) and possibly the MAb 3A1-specific epitope being unavailable (Fig. 2B). In agreement with this conformational change, quantitation of live surface-stained salivary gland sporozoites by flow cytometry indicates that only the NANP repeat-specific MAb 1G2 has a strong interaction with the parasite's surface (Fig. 2C), while the other MAbs fail to react with the sporozoite surface. Next, we analyzed the reactivity patterns of the CSP MAb panel using a sporozoite motility assay. The various patterns of CSP which were deposited are shown in Fig. 2D and subsequently scored for the absence or presence of deposited trails using three groupings: no trails, 1 to 5 trails, and >5 trails (Fig. 2E). While the NANP repeat-specific MAb 1G2 yielded a pattern of CSP trails consistently observed by another repeat-specific antibody (36), the patterns obtained with MAbs 3B4, 4B3, and 3A1 were clearly different and consistent with the epitopes for which these MAbs are specific being structurally less available or absent. Sporozoites incubated with MAb 1G2 plus cytochalasin D had limited or no mobility. Finally, we were able to examine a limited number of live sporozoites released by mosquitoes during probing. These are the mature parasites that would be injected into the human host. These sporozoites were also stained by the NANP repeat-specific MAb 1G2 (10/10 parasites), but none were detected with MAb 3B4 (0/8) (Fig. 2F), providing further evidence that the MAb 3B4-specific epitope is masked in the parasites that are injected into the human host.

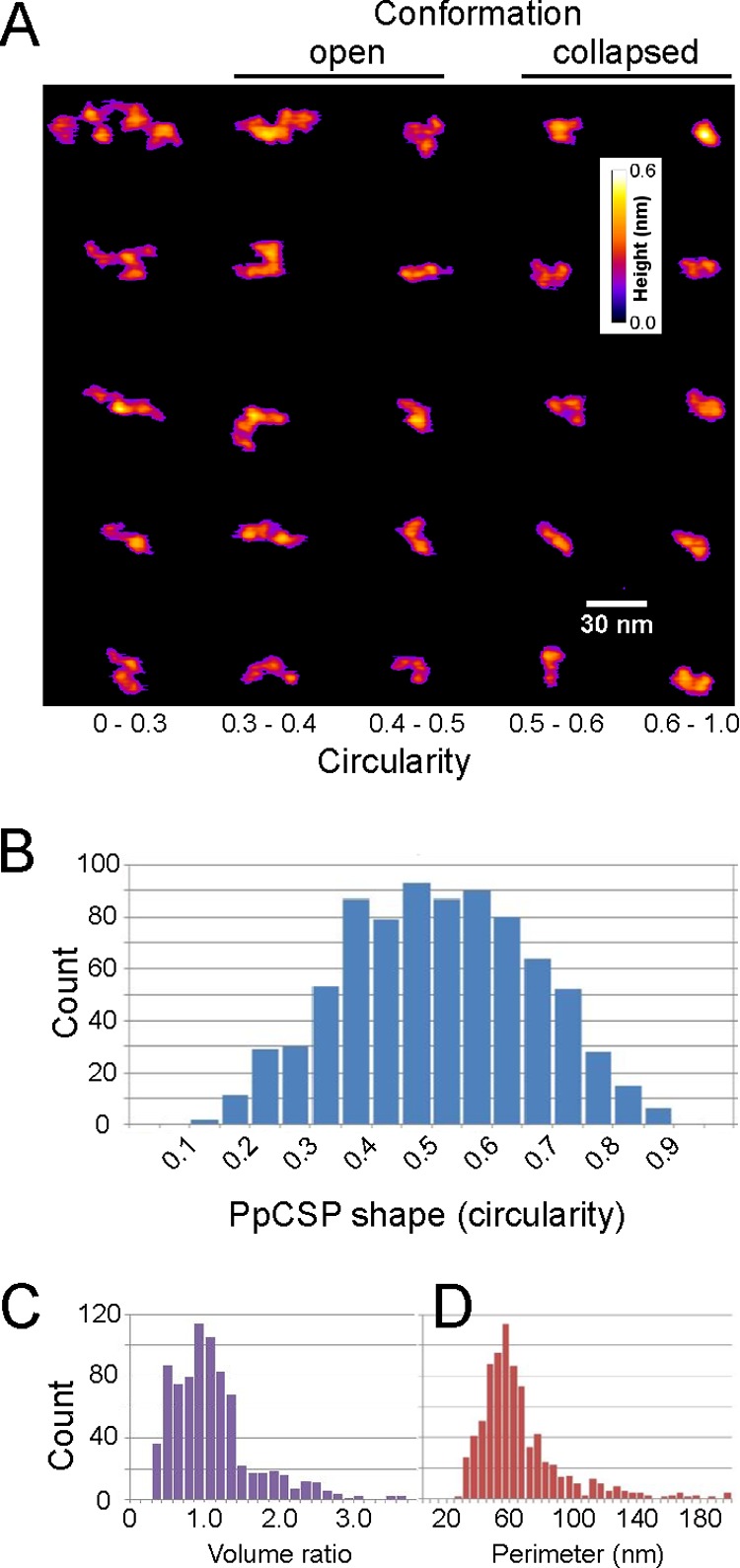

Bimodal distribution of two conformations of recombinant CSP.

The potential for conformational changes in native CSP was further investigated by analyzing the shape of recombinant PpCSP using atomic force microscopy. The volume, area, and perimeter of monomers of individual molecules were determined and used to calculate their circularity (Fig. 3A and B). Multiple levels of circularity that define two different conformations were found: an open monomer with a filamentous shape and a circularity ranging from 0.3 to 0.5 and a collapsed monomer with a compact shape (circularity range, 0.5 to 1.0) (Fig. 3B). Both shapes yielded similar distributions of volumes (Fig. 3C) and perimeters (Fig. 3D), demonstrating the integrity of the individual proteins. The recent observation that Ca2+ binds the CSP repeat region (37) leaves open the possibility that that there may be a role for Ca2+ binding and the change in CSP conformation observed here.

FIG 3.

Bimodal distribution of conformational changes in PpCSP. PpCSP particles were analyzed by atomic force microscopy, and a representative panel of individual proteins (A) and their associated circularity (B), their volume ratios (C) normalized to the expected monomer size of 35 nm3, and perimeters (D) are shown.

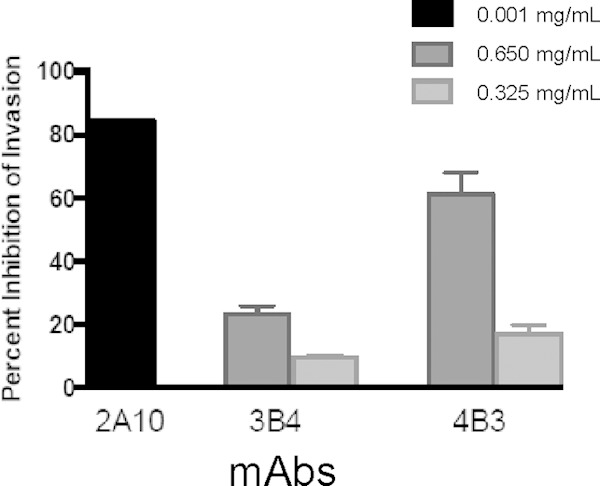

Inhibition of sporozoite invasion, in vitro.

We reported previously that TSR-specific MAbs block sporozoite invasion of hepatocytes in vitro (11). We show here that MAb 3B4, which targets region 1, also blocks sporozoite invasion, although to a lesser extent than the TSR-specific MAb 4B3 or another NANP repeat-specific MAb, MAb 2A10 (Fig. 4). These observations are consistent with those of Rathore and colleagues (24), who showed that antiserum generated against a synthetic peptide derived from a similar region also blocked sporozoite invasion in vitro. Recently, Espinosa and colleagues (38) showed that an N-terminal P. falciparum CSP-specific MAb, MAb 5D5, that mapped close to the region 1 cleavage site reported for Plasmodium berghei was able to inhibit CSP cleavage in P. falciparum salivary gland sporozoites in vitro. Furthermore, MAb 5D5 protects mice against a transgenic P. berghei CSP-PfCSP sporozoite challenge in passive immunization studies. The observations that the N terminus of CSP in proximity to region 1 is susceptible to interference by antibodies suggest that CSP reverts back to an open conformation during liver invasion, revealing both the region 1 and TSR epitopes.

FIG 4.

Percent inhibition of sporozoite invasion of hepatocytes in vitro using CSP-specific MAbs 2A10, 3B4, and 4B3.

Conclusion.

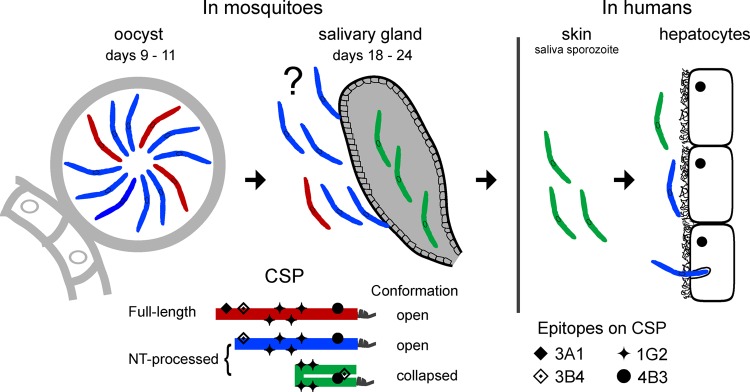

We propose that sporozoites have a full-length CSP in an open conformation when they develop in the mosquito midgut (see the schematic in Fig. 5), enabling region 1 and surrounding charged amino acids to interact with a receptor on the surface of salivary glands to facilitate invasion (25). Full-length CSP is subsequently processed upstream of region 1, although the precise nature of this process remains unclear. Once a sporozoite reaches the salivary glands, the conformation of CSP may collapse, thereby masking the functional N- and C-terminal domains. We speculate that CSP molecules remain in the collapsed conformation immediately following entry into the dermis and revert to an open conformation upon sporozoite invasion of a hepatocyte. This is in agreement with previous findings in the rodent model suggesting that P. berghei CSP changes conformation upon reaching the liver (10). Whether a collapsed conformation is due to an intramolecular interaction, as depicted in Fig. 5, or an intermolecular interaction remains unknown. The open conformation allows an interaction between the cell surface and the charged N terminus and subsequently results in the exposure of the TSR domain. Our findings demonstrate that native CSP has two different conformations. If the collapsed conformation is the one accessible to the human immune system the majority of the time, stabilization of this conformation in a new vaccine could greatly improve its efficacy. The level of protection conferred in vivo in response to a CSP immunogen with a collapsed conformation remains to be determined.

FIG 5.

Biochemical and biophysical changes in CSP and its role during the sporozoite's journey. The key at the bottom represents the different forms and conformations observed for the CSP and the locations of various epitopes of the CSP-specific MAbs. The question mark notes that the form and conformation of CSP in hemolymph sporozoites are speculative.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Solomon Conteh for purifying the salivary gland sporozoites, Emma Barnafo for technical assistance with the formulation of recombinant CSP, Andrew Orcutt for performing ELISAs, Carl Hammer and Mark Garfield for analytical support regarding the characterization of recombinant CS proteins, and Jan Lukszo from the Research Technology Branch, NIAID, for synthesizing the T9832 circumsporozoite peptide. Finally, we appreciate Louis Miller for his support and helpful discussion.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, including NIAID and NIBIB, and was also supported in part with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation under grant number 42387 to S. G. Reed.

S. G. Reed is a founder of and holds an equity interest in Immune Design, a licensee of certain rights associated with the glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.02676-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois AC, Khim N, Kim S, Duru V, Bouchier C, Ma L, Lim P, Leang R, Duong S, Sreng S, Suon S, Chuor CM, Bout DM, Menard S, Rogers WO, Genton B, Fandeur T, Miotto O, Ringwald P, Le Bras J, Berry A, Barale JC, Fairhurst RM, Benoit-Vical F, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Menard D. 2014. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 505:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoute JA, Slaoui M, Heppner DG, Momin P, Kester KE, Desmons P, Wellde BT, Garcon N, Krzych U, Marchand M. 1997. A preliminary evaluation of a recombinant circumsporozoite protein vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. RTS,S Malaria Vaccine Evaluation Group. N Engl J Med 336:86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agnandji ST, Lell B, Soulanoudjingar SS, Fernandes JF, Abossolo BP, Conzelmann C, Methogo BG, Doucka Y, Flamen A, Mordmuller B, Issifou S, Kremsner PG, Sacarlal J, Aide P, Lanaspa M, Aponte JJ, Nhamuave A, Quelhas D, Bassat Q, Mandjate S, Macete E, Alonso P, Abdulla S, Salim N, Juma O, Shomari M, Shubis K, Machera F, Hamad AS, Minja R, Mtoro A, Sykes A, Ahmed S, Urassa AM, Ali AM, Mwangoka G, Tanner M, Tinto H, D'Alessandro U, Sorgho H, Valea I, Tahita MC, Kabore W, Ouedraogo S, Sandrine Y, Guiguemde RT, Ouedraogo JB, Hamel MJ, Kariuki S, Odero C, et al. 2011. First results of phase 3 trial of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in African children. N Engl J Med 365:1863–1875. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agnandji ST, Lell B, Fernandes JF, Abossolo BP, Methogo BG, Kabwende AL, Adegnika AA, Mordmuller B, Issifou S, Kremsner PG, Sacarlal J, Aide P, Lanaspa M, Aponte JJ, Machevo S, Acacio S, Bulo H, Sigauque B, Macete E, Alonso P, Abdulla S, Salim N, Minja R, Mpina M, Ahmed S, Ali AM, Mtoro AT, Hamad AS, Mutani P, Tanner M, Tinto H, D'Alessandro U, Sorgho H, Valea I, Bihoun B, Guiraud I, Kabore B, Sombie O, Guiguemde RT, Ouedraogo JB, Hamel MJ, Kariuki S, Oneko M, Odero C, Otieno K, Awino N, McMorrow M, Muturi-Kioi V, Laserson KF, Slutsker L, et al. 2012. A phase 3 trial of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in African infants. N Engl J Med 367:2284–2295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bongfen SE, Ntsama PM, Offner S, Smith T, Felger I, Tanner M, Alonso P, Nebie I, Romero JF, Silvie O, Torgler R, Corradin G. 2009. The N-terminal domain of Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein represents a target of protective immunity. Vaccine 27:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Julien JP, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumkis D, Deller MC, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Ward AB, Wilson IA. 2013. Crystal structure of a soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science 342:1477–1483. doi: 10.1126/science.1245625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ringe RP, Sanders RW, Yasmeen A, Kim HJ, Lee JH, Cupo A, Korzun J, Derking R, van Montfort T, Julien JP, Wilson IA, Klasse PJ, Ward AB, Moore JP. 2013. Cleavage strongly influences whether soluble HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimers adopt a native-like conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:18256–18261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314351110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srinivasan P, Ekanem E, Diouf A, Tonkin ML, Miura K, Boulanger MJ, Long CA, Narum DL, Miller LH. 2014. Immunization with a functional protein complex required for erythrocyte invasion protects against lethal malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:10311–10316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409928111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coppi A, Natarajan R, Pradel G, Bennett BL, James ER, Roggero MA, Corradin G, Persson C, Tewari R, Sinnis P. 2011. The malaria circumsporozoite protein has two functional domains, each with distinct roles as sporozoites journey from mosquito to mammalian host. J Exp Med 208:341–356. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coppi A, Pinzon-Ortiz C, Hutter C, Sinnis P. 2005. The Plasmodium circumsporozoite protein is proteolytically processed during cell invasion. J Exp Med 201:27–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plassmeyer ML, Reiter K, Shimp RL Jr, Kotova S, Smith PD, Hurt DE, House B, Zou X, Zhang Y, Hickman M, Uchime O, Herrera R, Nguyen V, Glen J, Lebowitz J, Jin AJ, Miller LH, MacDonald NJ, Wu Y, Narum DL. 2009. Structure of the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein, a leading malaria vaccine candidate. J Biol Chem 284:26951–26963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miura K, Orcutt AC, Muratova OV, Miller LH, Saul A, Long CA. 2008. Development and characterization of a standardized ELISA including a reference serum on each plate to detect antibodies induced by experimental malaria vaccines. Vaccine 26:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozaki LS, Gwadz RW, Godson GN. 1984. Simple centrifugation method for rapid separation of sporozoites from mosquitoes. J Parasitol 70:831–833. doi: 10.2307/3281779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy M, Fishbaugher ME, Vaughan AM, Patrapuvich R, Boonhok R, Yimamnuaychok N, Rezakhani N, Metzger P, Ponpuak M, Sattabongkot J, Kappe SH, Hume JC, Lindner SE. 2012. A rapid and scalable density gradient purification method for Plasmodium sporozoites. Malar J 11:421. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimp RL Jr, Rowe C, Reiter K, Chen B, Nguyen V, Aebig J, Rausch KM, Kumar K, Wu Y, Jin AJ, Jones DS, Narum DL. 2013. Development of a Pfs25-EPA malaria transmission blocking vaccine as a chemically conjugated nanoparticle. Vaccine 31:2954–2962. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ejigiri I, Ragheb DR, Pino P, Coppi A, Bennett BL, Soldati-Favre D, Sinnis P. 2012. Shedding of TRAP by a rhomboid protease from the malaria sporozoite surface is essential for gliding motility and sporozoite infectivity. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002725. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coppi A, Cabinian M, Mirelman D, Sinnis P. 2006. Antimalarial activity of allicin, a biologically active compound from garlic cloves. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1731–1737. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1731-1737.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinzon-Ortiz C, Friedman J, Esko J, Sinnis P. 2001. The binding of the circumsporozoite protein to cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans is required for Plasmodium sporozoite attachment to target cells. J Biol Chem 276:26784–26791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104038200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lumsden JM, Pichyangkul S, Srichairatanakul U, Yongvanitchit K, Limsalakpetch A, Nurmukhambetova S, Klein J, Bertholet S, Vedvick TS, Reed SG, Sattabongkot J, Bennett JW, Polhemus ME, Ockenhouse CF, Howard RF, Yadava A. 2011. Evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity in rhesus monkeys of a recombinant malaria vaccine for Plasmodium vivax with a synthetic Toll-like receptor 4 agonist formulated in an emulsion. Infect Immun 79:3492–3500. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05257-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kastenmuller K, Espinosa DA, Trager L, Stoyanov C, Salazar AM, Pokalwar S, Singh S, Dutta S, Ockenhouse CF, Zavala F, Seder RA. 2013. Full-length Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein administered with long-chain poly(I·C) or the Toll-like receptor 4 agonist glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant-stable emulsion elicits potent antibody and CD4+ T cell immunity and protection in mice. Infect Immun 81:789–800. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01108-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rathore D, Hrstka SC, Sacci JB Jr, De la Vega P, Linhardt RJ, Kumar S, McCutchan TF. 2003. Molecular mechanism of host specificity in Plasmodium falciparum infection: role of circumsporozoite protein. J Biol Chem 278:40905–40910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coppi A, Tewari R, Bishop JR, Bennett BL, Lawrence R, Esko JD, Billker O, Sinnis P. 2007. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans provide a signal to Plasmodium sporozoites to stop migrating and productively invade host cells. Cell Host Microbe 2:316–327. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doud MB, Koksal AC, Mi LZ, Song G, Lu C, Springer TA. 2012. Unexpected fold in the circumsporozoite protein target of malaria vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:7817–7822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205737109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rathore D, Nagarkatti R, Jani D, Chattopadhyay R, de la Vega P, Kumar S, McCutchan TF. 2005. An immunologically cryptic epitope of Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein facilitates liver cell recognition and induces protective antibodies that block liver cell invasion. J Biol Chem 280:20524–20529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414254200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myung JM, Marshall P, Sinnis P. 2004. The Plasmodium circumsporozoite protein is involved in mosquito salivary gland invasion by sporozoites. Mol Biochem Parasitol 133:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nardin EH, Nussenzweig V, Nussenzweig RS, Collins WE, Harinasuta KT, Tapchaisri P, Chomcharn Y. 1982. Circumsporozoite proteins of human malaria parasites Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax. J Exp Med 156:20–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santoro F, Cochrane AH, Nussenzweig V, Nardin EH, Nussenzweig RS, Gwadz RW, Ferreira A. 1983. Structural similarities among the protective antigens of sporozoites from different species of malaria parasites. J Biol Chem 258:3341–3345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boulanger N, Matile H, Betschart B. 1988. Formation of the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum in Anopheles stephensi. Acta Trop 45:55–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva JC, Gorenstein MV, Li GZ, Vissers JP, Geromanos SJ. 2006. Absolute quantification of proteins by LCMSE: a virtue of parallel MS acquisition. Mol Cell Proteomics 5:144–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh AP, Buscaglia CA, Wang Q, Levay A, Nussenzweig DR, Walker JR, Winzeler EA, Fujii H, Fontoura BM, Nussenzweig V. 2007. Plasmodium circumsporozoite protein promotes the development of the liver stages of the parasite. Cell 131:492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez-Ceron L, Rodriguez MH, Wirtz RA, Sina BJ, Palomeque OL, Nettel JA, Tsutsumi V. 1998. Plasmodium vivax: a monoclonal antibody recognizes a circumsporozoite protein precursor on the sporozoite surface. Exp Parasitol 90:203–211. doi: 10.1006/expr.1998.4334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holder AA, Blackman MJ, Burghaus PA, Chappel JA, Ling IT, McCallum-Deighton N, Shai S. 1992. A malaria merozoite surface protein (MSP1)—structure, processing and function. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 87(Suppl 3):S37–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Remarque EJ, Faber BW, Kocken CH, Thomas AW. 2008. Apical membrane antigen 1: a malaria vaccine candidate in review. Trends Parasitol 24:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howard RF, Narum DL, Blackman M, Thurman J. 1998. Analysis of the processing of Plasmodium falciparum rhoptry-associated protein 1 and localization of Pr86 to schizont rhoptries and p67 to free merozoites. Mol Biochem Parasitol 92:111–122. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(97)00238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Narum DL, Thomas AW. 1994. Differential localization of full-length and processed forms of PF83/AMA-1 an apical membrane antigen of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Mol Biochem Parasitol 67:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Persson C, Oliveira GA, Sultan AA, Bhanot P, Nussenzweig V, Nardin E. 2002. Cutting edge: a new tool to evaluate human pre-erythrocytic malaria vaccines: rodent parasites bearing a hybrid Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein. J Immunol 169:6681–6685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Topchiy E, Lehmann T. 2014. Chelation of Ca2+ ions by a peptide from the repeat region of the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein. Malar J 13:195. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Espinosa DA, Gutierrez GM, Rojas-Lopez M, Noe AR, Shi L, Tse SW, Sinnis P, Zavala F. 11 March 2015. Proteolytic cleavage of the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein is a target of protective antibodies. J Infect Dis doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.