Abstract

Objectives

To measure the prevalence and incidence of delirium in older adults as they transition from the emergency department (ED) to the inpatient ward, and to determine the association between delirium during early hospitalisation and subsequent clinical deterioration.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Urban tertiary care hospital in Bronx, New York.

Participants

Adults aged 65 years or older admitted to the inpatient ward from the ED (n=260).

Measurements

Beginning in the ED, delirium was assessed daily for 3 days, using the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit.

Outcomes

(1) Clinical deterioration, defined as unanticipated intensive care unit (ICU) admission or in-hospital death (primary outcome); (2) decline in discharge status, defined as discharge to higher level of care, hospice or in-hospital death.

Results

38 of 260 participants (15%) were delirious at least once during the first 3 days of hospitalisation. Of the 29 (11%) patients with delirium in the ED (ie, hospital day 1), delirium persisted into hospital day 2 in 72% (n=21), and persisted for all 3 days in 52% (n=15). In multivariate analyses, as little as 1 episode of delirium during the first 3 days was associated with increased odds of unanticipated ICU admission or in-hospital death (adjusted OR 8.07 (95% CI 1.91 to 34.14); p=0.005). Delirium that persisted for all 3 days was associated with a decline in discharge status, even after adjusting for factors such as severity of illness and baseline cognitive impairment (adjusted OR 4.70 (95% CI 1.41 to 15.63); p=0.012).

Conclusions

Delirium during the first few days of hospitalisation was associated with poor outcomes in older adults admitted from the ED to the inpatient ward. These findings suggest the need for serial delirium monitoring that begins in the ED to identify a high-risk population that may benefit from closer follow-up and intervention.

Keywords: GERIATRIC MEDICINE, INTERNAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Delirium was assessed in all patients on a daily basis across emergency department (ED) and inpatient ward settings.

Confounding factors, such as baseline cognitive impairment, were prospectively measured.

The Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) was recently found to be moderately sensitive and highly specific for diagnosing delirium in older ED patients.

Given the small number of events, multivariate models may have been limited by inadequate adjustment for confounders and overfitting.

Delirium assessments were limited to the first 3 days of hospitalisation. However, it is remarkable that delirium status over such a short period of time can still be predictive of poor outcomes.

Introduction

Delirium is a form of acute cognitive impairment that is common in older emergency department (ED) patients and inpatients.1–3 It is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and accounts for up to $152 billion in annual health-related costs in the USA.1 The short-term and long-term consequences of delirium in older adults in the ED and in the inpatient ward have been well described and include increased hospital length of stay, institutionalisation, accelerated cognitive decline, functional impairment and even increased risk of death.4–10

Previous studies have examined the prevalence and outcomes of delirium in the ED and in the inpatient ward as distinct clinical settings. To our knowledge, none have examined the outcomes of delirium that persists from ED to inpatient ward. This is an important gap in knowledge for several reasons. First, the transition from ED to inpatient ward represents an important point in time in the hospital course when patients are vulnerable to clinical deterioration despite adequate clinical care, and occasionally due to inadequate care (eg, unrecognised physiological abnormalities and triage error).11 Indeed, over 25% of rapid response calls occur within the first 2 days of admission and most unanticipated intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and in-hospital deaths occur within the first day of hospitalisation.12 13 Second, studies have shown that a longer duration of delirium is associated with worse outcomes.14–17 Thus, delirium status that persists from the ED through early hospitalisation may be a prognostic marker of clinical deterioration and poor outcomes.

The objective of this study was to characterise the prevalence, incidence and duration of delirium diagnosed during first 3 days of hospitalisation, and to determine the short-term outcomes associated with delirium. We hypothesise that older patients with delirium during early hospitalisation are at an increased risk for clinical deterioration (ie, unanticipated ICU admission and/or in-hospital death) and decline in discharge status, defined as discharge to higher level of care, hospice or death.

Methods

Study design and population

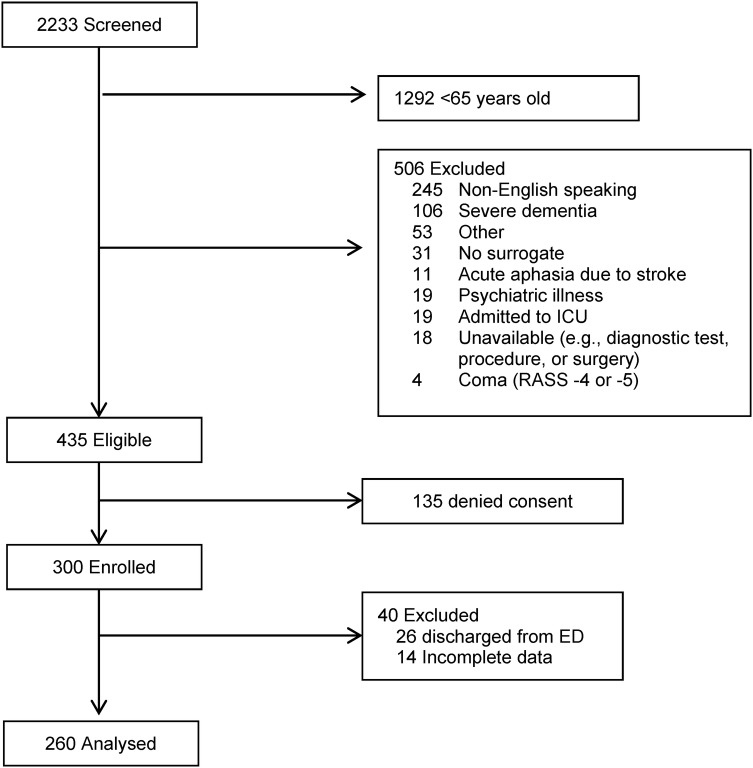

This prospective cohort study was conducted in a tertiary care, urban academic hospital in Bronx, New York, from July 2011 to November 2011. Consecutive ED patients were screened for eligibility Monday through Friday from 7:00 to 19:00. This interval was chosen based on the typical time spent in the ED before hospital admission and the availability of research assistants (RAs). Patients were eligible for enrolment if they were 65 years or older and were listed for admission to a non-ICU inpatient ward. Verbal consent was obtained from the patient by trained study staff. If the patient lacked capacity to make clinical decisions or was delirious, consent was obtained from the surrogate. Patients were excluded if they were directly admitted from the ED to the ICU, were non-English speaking, were unable to be assessed for delirium (eg, comatose, severe dementia, severe psychiatric illness), or were unavailable due to diagnostic tests or procedures (figure 1). Patients who were admitted to the hospital but were subsequently discharged from the ED, eloped or signed out against medical advice were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1.

Summary of participant enrolment (ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; RASS, Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale).

Measurement of delirium and covariates

Delirium, level of consciousness, dementia and functional status were prospectively assessed by trained RAs comprised of medical students, internal medicine residents and critical care fellows. Prior to initiation of the study, RAs received 2 weeks of intensive training which included a detailed review of the study protocol, practice sessions on obtaining informed consent and observed demonstrations of study procedures. Training in delirium assessment included supervised performance of the delirium assessment, and iterative practice sessions in which the RA and trainer independently performed delirium assessments within several hours of each other on a minimum of 12 patients. The RA was allowed to participate in study procedures once complete agreement between delirium assessments was achieved.

Trained RAs assessed patients for delirium once daily for three consecutive days beginning in the ED using the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU).18 The CAM-ICU was chosen due to its ease of use and rapid administration. Compared to a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) reference standard, the CAM-ICU was recently shown to be highly reliable (κ 0.92), moderately sensitive (68%) and highly specific (99%) for detecting delirium in older ED patients when performed by trained RAs.19 Level of consciousness was assessed each day using the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS). Coma was defined as a RASS score of −4 or −5.20 21 Delirium was measured once daily on the first 3 days of admission (ie, hospital day 1=ED, hospital day 2, hospital day 3). Delirium was characterised in two different ways: (1) as a binary variable (never vs ever delirious), and (2) as a categorical variable (0–3 days of delirium). We also performed an exploratory analysis in which delirium was classified based on resolution status: never delirious, resolved delirium (eg, delirious in ED and not delirious on hospital day 2 or 3), incident delirium (eg, not delirious in ED and delirious on hospital day 2 or 3) and persistent delirium (eg, delirious in ED through hospital day 3).

Covariates were collected at the time of enrolment and during hospitalisation. These included age, years of education and home medications known to precipitate delirium (eg, benzodiazepines, narcotics and antipsychotics).22 ED medical records were reviewed for documentation of delirium or altered mental status by the ED physician or nurse. Baseline cognitive function was determined using the Memory Impairment Screen (MIS) if the patient was not delirious, and by surrogate interview using the short-form Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) score if the patient was delirious. Cognitive impairment was defined as a MIS score of 4 or less,23 or a IQCODE score of greater than 3.38.24 25 Baseline functional status was determined using the Katz Activities of Daily Living (Katz ADL), which has been validated for both patient and surrogate use. Functional impairment was defined as a Katz ADL score of 4 or less.26 Comorbidity burden was assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index.27 Severity of illness at the time of admission was measured using the Rapid Emergency Medicine Score (REMS), a scoring system of six routinely available physiological measurements that is predictive of in-hospital mortality in non-surgical ED patients.28 29 Because the Glasgow Coma Score was not uniformly measured in all patients, we modified the REMS by assigning a score of 1 if altered mental status was documented in ED records and a score of 0 if it was not, similar to previous studies.30 31 The predictive ability for in-hospital mortality is similar between the modified and original REMS.31

Outcome variables

The primary outcome for this study was clinical deterioration during hospitalisation, defined as unanticipated ICU admission or in-hospital death. Unanticipated ICU admission was defined as admission to an ICU at any time during hospitalisation in patients who were initially admitted to a regular inpatient ward from the ED. Patients who were directly admitted to the ICU from the ED were excluded from the study. We chose a combined outcome of unanticipated ICU admission or death to measure clinical deterioration in a cohort of patients admitted to the inpatient ward. While not equivalent, unanticipated ICU admission is associated with a much higher mortality rate than planned ICU admissions (up to 60%) and is more costly to treat.32 33 In addition, unanticipated ICU admission has profound implications for the overall health trajectory of older adults, and is frequently combined with in-hospital mortality as the clinical end point for studying the efficacy of early warning systems.34 Secondary outcomes were (1) decline in discharge status, (2) critical care consultation, (3) organ failure and (4) hospital length of stay. Decline in discharge status is a patient-centred outcome defined as discharge to higher level of care compared with prehospital residence (eg, home to nursing home and rehabilitation centre to nursing home), hospice or in-hospital death. Because of its clinical relevance to both outcomes, in-hospital death was included a priori in both primary (ie, clinical deterioration during hospitalisation) and secondary outcomes (ie, decline in discharge status). Organ failure was assessed using the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score,35 36 which was generated using the most abnormal values during the first 3 days of hospitalisation.

Data analysis

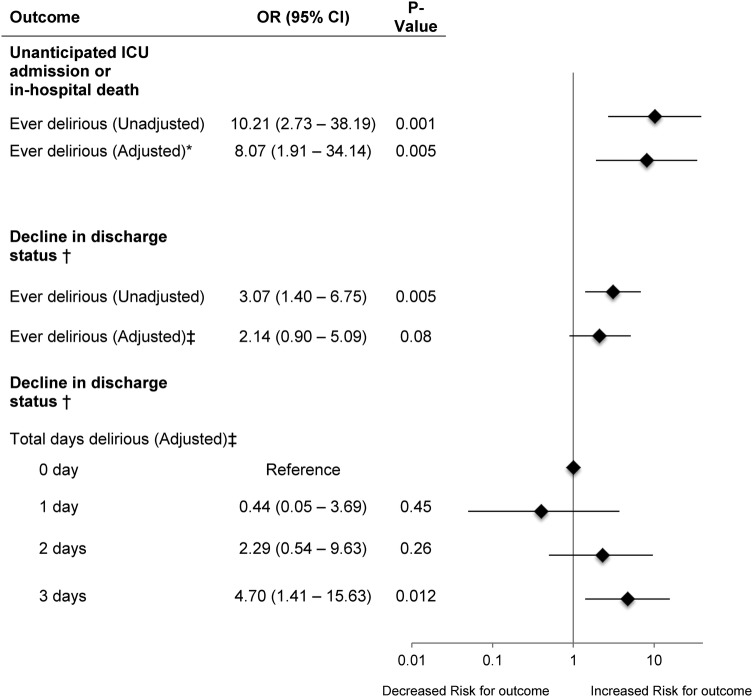

Categorical data were analysed by χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Normally distributed continuous variables were analysed by t test or analysis of variance. Non-parametric continuous variables were analysed using Wilcoxon rank-sum or Kruskal-Wallis test. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05, using two-tailed tests of hypotheses. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to determine if delirium was independently associated with (1) a combined outcome of death or unanticipated ICU admission, and (2) decline in discharge status. Our primary independent variable was delirium, represented as a binary variable (ie, ever vs never delirious during first 3 days of hospitalisation). Delirium was also analysed as an ordinal variable (ie, 0–3 days, with 0 days of delirium as the reference). Covariates that were risk factors for the outcomes were selected a priori based on previous studies, namely age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, REMS, baseline cognitive and functional impairment.28 37–39 Because both outcomes had a small number of events, parsimonious regression models were used to avoid overfitting. For the primary outcome of unanticipated ICU admission or death (n=10 events), delirium was analysed as a binary variable and we only included covariates with a prespecified level of association with the outcome in unadjusted analyses (p<0.2; see online supplementary table S1). For the secondary outcome of decline in discharge status (n=41 events), two separate multivariate logistic regression models were used to evaluate delirium as a binary predictor (ever vs never) and as an ordinal variable (0=reference, 1, 2, 3 days; figure 2). We limited the model to three additional covariates (p<0.1 in unadjusted analyses) to avoid overfitting (see online supplementary table S2). Model fit and specification were checked with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and link test, respectively; all of which were satisfactory. Bootstrap validation was used to assess final models for overfitting. The original data were resampled 500 times and yielded similar estimates (see online supplementary tables S1 and S2).40 All statistical analyses were performed using STATA V.13 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Figure 2.

Association between delirium during early hospitalisation and poor outcomes. Adjusted for age and REMS. Decline in discharge status is defined as discharge to higher level of care, hospice or in-hospital death. Adjusted for age, REMS, cognitive impairment (MIS ≤4 or IQCODE >3.38). ICU, intensive care unit; IQCODE, Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly score; MIS, Memory Impairment Screen score; REMS, Rapid Emergency Medicine Score.

Results

A total of 941 ED patients >65 years old were screened. Of 435 eligible patients, 300 were enrolled (figure 1). Of note, 245 (26%) non-English speakers were excluded; this proportion is reflective of the demographics of the Bronx.41 The gender, race and age of patients who declined consent (n=135) did not significantly differ from enrolled patients. Of the 300 enrolled patients, 40 patients were excluded from the final analyses; 26 patients were discharged home from the ED and 14 patients had incomplete data.

Of the 260 analysed patients, the median hospital length of stay was 5 days (IQR 3–8); 29 patients (11%) were delirious in the ED and 38 (15%) experienced at least one episode of delirium during their first three days of hospitalisation. Notably, delirium and/or altered mental status were not documented in the ED chart for 15 of the 29 patients (52%) who were CAM-ICU positive in the ED. Of the 29 patients with delirium in the ED (ie, hospital day 1), delirium resolved by hospital day 2 in 28% (n=8) and by hospital day 3 in 21% (n=6); delirium persisted for all 2 days in 52% (n=15). In addition, nine patients without delirium in the ED developed incident delirium on hospital day 2 (n=4) and day 3 (n=5). None of the patients had delirium on hospital day 1 and on hospital day 3, but not on hospital day 2.

Patients who experienced at least one episode of delirium during the first 3 days of hospitalisation were older, had more baseline functional impairment and dementia, were admitted from a nursing home more often, had higher severity of illness, and were more frequently admitted with infection and musculoskeletal problems compared with patients without delirium (p<0.05, table 1). Delirium was not associated with gender, race, education or home use of deliriogenic medications (eg, benzodiazepines, opiates, antipsychotics).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Never delirious (n=222) | Ever delirious (n=38) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 136 (61) | 20 (53) | 0.32 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.31 | ||

| White | 57 (26) | 17 (45) | |

| Black | 106 (48) | 14 (37) | |

| Hispanic | 46 (21) | 6 (16) | |

| Other | 13 (6) | 1 (3) | |

| Age, mean±SD | 76±8 | 83±8 | <0.001 |

| Education (years), mean±SD | 11±4 | 11±4 | 0.78 |

| Prehospital residence, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Home | 199 (90) | 23 (61) | |

| Nursing home | 18 (8) | 15 (39) | |

| Other | 5 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 3 (1–5) | 0.07 |

| Dementia by medical record, n (%) | 15 (7) | 14 (37) | <0.001 |

| Prehospital cognitive impairment, n (%)* | 68 (31) | 24 (63) | <0.001 |

| Prehospital functional impairment, n (%)† | 44 (20) | 21 (57) | <0.001 |

| Outpatient benzodiazepine, opiate, or antipsychotic, n (%) | 37 (17) | 9 (24) | 0.29 |

| Altered mental status documented in ED chart, n (%) | 14 (6) | 16 (42) | <0.001 |

| Hospital admission diagnoses, n (%)‡ | |||

| Infection | 54 (24) | 16 (42) | 0.02 |

| Respiratory problem | 32 (14) | 4 (11) | 0.62 |

| Congestive heart failure | 25 (11) | 6 (16) | 0.42 |

| Other cardiac problems | 56 (25) | 7 (18) | 0.36 |

| Bleeding problems | 16 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.13 |

| Neurological problems | 15 (7) | 2 (5) | >0.99 |

| Kidney/genitourinary problems | 24 (11) | 2 (5) | 0.39 |

| Metabolic disturbances | 10 (5) | 3 (8) | 0.41 |

| Abdominal pain | 22 (10) | 4 (11) | >0.99 |

| Syncope | 19 (9) | 3 (8) | >0.99 |

| Musculoskeletal | 8 (4) | 5 (13) | 0.01 |

| Other | 12 (5) | 2 (5) | >0.99 |

| REMS, median (IQR) | 8 (7–9) | 9 (8–11) | 0.002 |

*Defined as Memory Impairment Screen score ≤4 or Informant Questionnaire for Cognitive Decline score >3.38.

†Defined as Katz activities of daily living score ≤4.

‡Sum is >100% because all diagnoses in admission notes were included.

ED, emergency department; REMS, Rapid Emergency Medicine Score.

In univariate analyses, patients with at least one episode of delirium during the first 3 days of hospitalisation had significantly greater critical care utilisation, unanticipated ICU admission, in-hospital death, hospital length of stay and decline in discharge status compared with non-delirious patients (table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes in patients with and without delirium between ED and hospital day 3

| Never delirious (n=222) | Ever delirious (n=38) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical deterioration, n (%)* | 4 (2) | 6 (16) | <0.001 |

| Unanticipated ICU admission, n (%)† | 2 (1) | 3 (8) | 0.02 |

| In-hospital death, n (%) | 2 (1) | 3 (8) | 0.02 |

| Critical care consult, n (%) | 14 (6) | 9 (24) | <0.001 |

| Organ failures during hospitalisation, n (%) | |||

| Liver failure | 31 (14) | 5 (13) | 0.89 |

| Cardiovascular failure | 26 (12) | 8 (21) | 0.11 |

| Coagulation failure | 7 (3) | 7 (18) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 31 (14) | 5 (13) | 0.89 |

| Any organ failure | 81 (37) | 19 (50) | 0.11 |

| Modified SOFA score, median (IQR)‡ | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–4) | 0.51 |

| Hospital length of stay (days), median (IQR) | 5 (3–7) | 6 (4–10) | 0.008 |

| Decline in discharge status, n (%)§ | 29 (13) | 12 (32) | 0.004 |

| Discharge location, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Died | 2 (1) | 3 (8) | |

| Home | 177 (80) | 16 (42) | |

| Nursing home | 29 (13) | 13 (34) | |

| Hospice | 2 (1) | 4 (11) | |

| Other | 12 (5) | 2 (5) |

Range 0 (best) to 24 (worst); generated using the worst physiological values during the first 3 days of hospitalisation.

*Defined as unanticipated ICU admission or in-hospital death.

†All patients who were admitted to the ICU survived hospitalisation.

‡Generated using the most abnormal values during the entire hospitalisation.

§Defined as discharge to higher level of care, hospice or in-hospital death.

ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score.

After adjusting for age and REMS, delirium within the first 3 days of hospitalisation remained significantly associated with clinical deterioration, defined as unanticipated ICU admission or in-hospital death (adjusted OR 8.07 (95% CI 1.91 to 34.14); p=0.005; figure 2, see online supplementary table S1). Of note, delirium preceded ICU admission for all patients. Delirium within the first 3 days of hospitalisation was not significantly associated with decline in discharge status after adjusting for age, REMS and baseline cognitive impairment (adjusted OR 2.14 (95% CI 0.90 to 5.09); p=0.08). However, this association was significant in patients with delirium that persisted from the ED through hospital day 3 when compared with patients with 0 days of delirium (adjusted OR 4.70 (95% CI 1.41 to 15.63); p=0.012; figure 2, see online supplementary table S2).

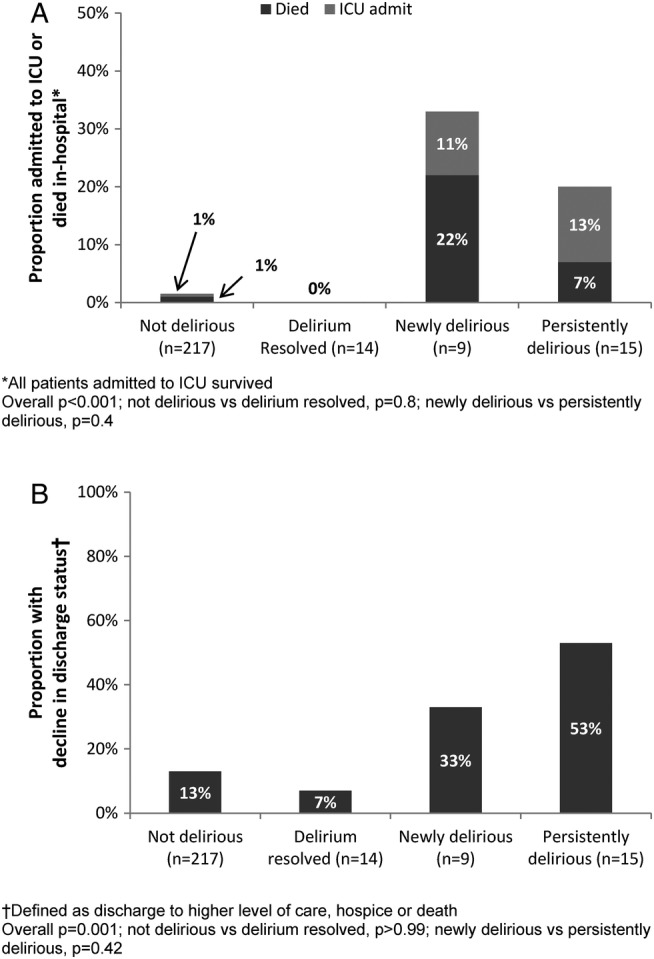

In an exploratory analysis, we compared clinical outcomes based on the course of delirium. Patients with persistent delirium (ie, ED through hospital day 3; n=15) and incident delirium (ie, no delirium in ED but delirium on day 2 or 3; n=9) had greater unanticipated ICU admissions, in-hospital deaths and decline in discharge status compared with ‘resolvers’ (ie, delirium in the ED and no delirium on hospital day 2 or 3; n=14) and to patients who did not become delirious during their first 3 days of hospitalisation (n=217; figure 3, see online supplementary table S3).

Figure 3.

Outcomes stratified by course of delirium (intensive care unit).

Discussion

Little is known about the clinical outcomes of older patients with delirium during their transition in care from the ED to inpatient ward. We found that delirium persists from the ED to the inpatient ward in nearly three-quarters of older patients, and that even one episode of delirium between the ED and hospital day 3 was associated with an increased risk for unanticipated ICU admission or in-hospital death. We also found that persistent delirium during early hospitalisation was associated with a higher risk for decline in discharge status, even after adjusting for important covariates. These findings are important because they identify delirium status during early hospitalisation as a useful prognostic factor for poor short-term outcomes, highlighting the clinical importance of early detection and serial delirium screening in older adults.

The first few days of hospitalisation is a period in which clinical deterioration (eg, unanticipated ICU admission, death) frequently occurs, either despite adequate care or due to inadequate clinical care.13 34 42 Cohort studies have suggested that clinical deterioration is predictable and preventable because it is often preceded by physiological abnormalities within 6–24 h.32 43–45 However, the relationship between delirium during early hospitalisation and clinical deterioration is unclear because this period has not been well studied: studies in ED cohorts did not assess patients for delirium after they were admitted and studies in inpatient cohorts often did not perform delirium assessments beginning in the ED.5 46 In our cohort, nearly half of patients with delirium in the ED were still delirious by hospital day 3; of these persistently delirious patients, 20% were either admitted to the ICU or died during their hospitalisation. These findings suggest that older inpatients with delirium that persists from the ED are at high risk for clinical deterioration. Future studies in larger cohorts are needed to further investigate this association and determine if early identification and treatment of delirium and its risk factors can prevent clinical deterioration in older inpatients.

While the underlying mechanism between delirium and poor outcomes is likely multifactorial, one possible explanation for the worse outcomes observed in patients with delirium that persisted from the ED to the inpatient ward is that delirium was unrecognised by clinical providers in both settings. In our cohort, delirium was not recognised in 52% of ED patients. Prior studies have reported similar rates of unrecognised delirium, ranging between 57% and 83%.2 47 48 Moreover, a previous study reported that over 90% of delirium that is missed in the ED is also missed in the hospital setting.2 Unrecognised delirium could have led to delays in a diagnostic workup for delirium, delays in initiating delirium interventions, a lack of appreciation for severity of illness, and inappropriate admission to the inpatient ward when a higher level of monitoring is needed. The clinical importance of unrecognised delirium has been highlighted by the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine Geriatric Task Force, which identified cognitive assessments as one of three key quality measures for care given to older ED patients.49 Our findings add to the growing literature supporting serial delirium screening that begins in the ED.

The association between a longer duration of delirium and poor outcomes has been well established in both inpatient and critically ill cohorts.15 16 50 However, less is known about outcomes associated with the timing of delirium development and resolution. A prior study in older medical inpatients found that patients whose delirium resolved within 24 h had better outcomes than patients whose delirium took longer to resolve.50 In our exploratory analyses, patients with ED delirium (ie, day 1) that resolved by hospital day 2 or 3 (ie, resolvers) had similar outcomes as patients who were not delirious in the ED. Specifically, none of the 14 resolvers were admitted to the ICU or died, and the proportion of resolvers with a downgrade in discharge status was similar to patients who were not delirious from the ED through hospital day 3 (p>0.99; figure 3, see online supplementary table S3). In contrast, patients who were not delirious in the ED but transitioned into delirium on hospital day 2 or 3 (ie, newly delirious) had rates of clinical deterioration and decline in discharge status that were similar to patients who were persistently delirious from the ED through hospital day 3 (p>0.4). Because these results were not adjusted for potential confounders, larger studies with multivariate analyses are needed to confirm our findings.

Strengths of this study include the prospective assessment of delirium across clinical settings and the prospective measurement of confounding risk factors for poor outcomes using validated instruments (ie, prehospital cognitive and functional status). Our study also has several limitations. First, the CAM-ICU has moderate sensitivity for detecting delirium in older ED patients when compared with DSM-IV criteria, and the CAM-ICU has not been validated in older patients admitted to the inpatient ward.19 While a modified version of the CAM-ICU (ie, the Brief Confusion Assessment Method) was recently found to be 80% sensitive and over 95% specific for diagnosing delirium in older inpatients relative to DSM-IV criteria, some delirious patients may have been misclassified as non-delirious.51 In addition, delirium assessments were performed once daily, and thus additional episodes of delirium may have been missed due to its fluctuating nature. However, these forms of misclassification would have likely biased our findings towards the null and would have underestimated the number of patients with delirium. Second, our delirium assessments were limited to the first 3 days of hospitalisation, so we cannot comment on delirium duration during the entire hospitalisation or incident delirium occurring later in the hospitalisation. However, it is remarkable that delirium status over such a short period of time can still be predictive of poor outcomes. Third, the number of outcome events in the cohort was small. Therefore, adjustment for subgroups of prevalent/incident delirium and additional covariates was limited, and the models may be subject to overfitting. However, evaluations for model fit and specification were adequate, and bootstrap validation yielded similar estimates. Fourth, because this was an observational study, unmeasured confounders may bias our findings. For example, we did not assess for prehospital depression, a potential confounder of the relationship between delirium and poor outcomes, nor iatrogenic causes of delirium after hospital admission (eg, sedative, Foley catheter and restraint use). Fifth, we excluded non-English speakers and enrolled patients from 7:00 to 19:00, Monday through Friday, which could have affected our estimates of delirium prevalence and may have introduced selection bias. Finally, this study was conducted at a single institution, which limits the generalisability of the results. Notwithstanding these limitations, our data raise some interesting questions about the timing of delirium development and resolution, and clinical outcomes associated with delirium during transitions in care that should be further investigated. Future studies in larger multicentre cohorts are needed to validate our findings and to determine if delirium reduction improves long-term outcomes.

Conclusion

Delirium during the first 3 days of hospitalisation is associated with greater unanticipated ICU admission and in-hospital mortality in older adults admitted to the inpatient ward. Furthermore, delirium that persists from the ED through early hospitalisation is associated with discharge to higher level of care, hospice or death, even after adjusting for age, severity of illness and baseline cognitive impairment. These findings suggest the need for serial delirium monitoring that begins in the ED to identify a population that is at high risk for poor short-term outcomes and that may benefit from closer follow-up.

Footnotes

Prior presentations: Some of the results of this study have been previously reported as abstracts at the American Thoracic Society International Conference, May 2012, San Francisco, CA, and Society of Critical Care Medicine Conference, January 2013, San Juan, Puerto Rico, USA.

Contributors: SJH, JZ and MNG were involved in study conception and design. SJH, PM, AAH and MNG were involved in data acquisition, analysis, interpretation. SJH, PM, AAH and MNG were involved in drafting of the manuscript. The authors thank the patients and family members at Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, who participated in this study, and acknowledge the data collection contributions of Krishna Aparnaji, MD; Samantha Selesny; Michael Shusterman; Koral Dadon; Hannah Esan; Sushruta Duara, MD; and Su B Park, MD.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging GEMSSTAR Program (RO3AG040673) and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine—Montefiore Medical Center Institute for Clinical and Translational Research Career Development Award (8KL2TR0000088–05) (SJ Hsieh); the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (HL086667, U01HL108712) (MN Gong); and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (1 UL1 TR001073, 1 TL1 TR001072, 1 KL2 TR001071) (Einstein-Montefiore CTSA).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y et al. . One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:27–32. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N et al. . Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:193–200. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00339.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014;383:911–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han JH, Eden S, Shintani A et al. . Delirium in older emergency department patients is an independent predictor of hospital length of stay. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:451–7. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01065.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han JH, Shintani A, Eden S et al. . Delirium in the emergency department: an independent predictor of death within 6months. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:244–52.e1. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Keeffe S, Lavan J. The prognostic significance of delirium in older hospital patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:174–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francis J, Kapoor WN. Prognosis after hospital discharge of older medical patients with delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40:601–6. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF et al. . Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2010;304:443–51. 10.1001/jama.2010.1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross AL, Jones RN, Habtemariam DA et al. . Delirium and long-term cognitive trajectory among persons with dementia. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1324–31. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leslie DL, Zhang Y, Holford TR et al. . Premature death associated with delirium at 1-year follow-up. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1657–62. 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litvak E, Pronovost PJ. Rethinking rapid response teams. JAMA 2010;304:1375–6. 10.1001/jama.2010.1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medical Emergency Team End-of-Life Care investigators. The timing of Rapid-Response Team activations: a multicentre international study. Crit Care Resusc 2013;15:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey TC, Chen Y, Mao Y et al. . A trial of a real-time alert for clinical deterioration in patients hospitalized on general medical wards. J Hosp Med 2013;8:236–42. 10.1002/jhm.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez M, Martinez G, Calderon J et al. . Impact of delirium on short-term mortality in elderly inpatients: a prospective cohort study. Psychosomatics 2009;50:234–8. 10.1176/appi.psy.50.3.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Ely EW. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2014;370:185–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brummel NE, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP et al. . Delirium in the ICU and subsequent long-term disability among survivors of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 2014;42:369–77. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a645bd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quinlan N, Rudolph JL. Postoperative delirium and functional decline after noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59(Suppl 2):S301–4. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03679.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J et al. . Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med 2001;29:1370–9. 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han JH, Wilson A, Graves AJ et al. . Validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:180–7. 10.1111/acem.12309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A et al. . Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA 2003;289:2983–91. 10.1001/jama.289.22.2983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ et al. . The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:1338–44. 10.1164/rccm.2107138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wierenga PC, Buurman BM, Parlevliet JL et al. . Association between acute geriatric syndromes and medication-related hospital admissions. Drugs Aging 2012;29:691–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buschke H, Kuslansky G, Katz M et al. . Screening for dementia with the Memory Impairment Screen. Neurology 1999;52:231–8. 10.1212/WNL.52.2.231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): development and cross-validation. Psychol Med 1994;24:145–53. 10.1017/S003329170002691X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jorm AF, Scott R, Cullen JS et al. . Performance of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) as a screening test for dementia. Psychol Med 1991;21:785–90. 10.1017/S0033291700022418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW et al. . Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963;185:914–19. 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL et al. . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsson T, Terent A, Lind L. Rapid Emergency Medicine score: a new prognostic tool for in-hospital mortality in nonsurgical emergency department patients. J Intern Med 2004;255:579–87. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01321.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olsson T, Lind L. Comparison of the Rapid Emergency Medicine Score and APACHE II in nonsurgical emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 2003;10:1040–8. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00572.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crowe CA, Kulstad EB, Mistry CD et al. . Comparison of severity of illness scoring systems in the prediction of hospital mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2010;3:342–7. 10.4103/0974-2700.70761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howell MD, Donnino MW, Talmor D et al. . Performance of severity of illness scoring systems in emergency department patients with infection. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:709–14. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.tb01866.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McQuillan P, Pilkington S, Allan A et al. . Confidential inquiry into quality of care before admission to intensive care. BMJ 1998;316:1853–8. 10.1136/bmj.316.7148.1853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rapoport J, Teres D, Lemeshow S et al. . Timing of intensive care unit admission in relation to ICU outcome. Crit Care Med 1990;18:1231–5. 10.1097/00003246-199011000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGaughey J, Alderdice F, Fowler R et al. . Outreach and Early Warning Systems (EWS) for the prevention of intensive care admission and death of critically ill adult patients on general hospital wards. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(3):CD005529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J et al. . The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:707–10. 10.1007/BF01709751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A et al. . Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA 2001;286:1754–8. 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inouye SK, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI et al. . A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:474–81. 10.7326/0003-4819-119-6-199309150-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ et al. . Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13: 204–12. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00047.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schor JD, Levkoff SE, Lipsitz LA et al. . Risk factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA 1992;267:827–31. 10.1001/jama.1992.03480060073033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.U.S. Department of Commerce. United States Census QuickFacts Beta—Bronx County. Secondary United States Census QuickFacts Beta—Bronx County 2013. http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/POP815213/00,36005 (accessed 26 Apr 2014).

- 42.Young MP, Gooder VJ, McBride K et al. . Inpatient transfers to the intensive care unit: delays are associated with increased mortality and morbidity. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:77–83. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20441.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hillman KM, Bristow PJ, Chey T et al. . Antecedents to hospital deaths. Intern Med J 2001;31:343–8. 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2001.00077.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kause J, Smith G, Prytherch D et al. . A comparison of antecedents to cardiac arrests, deaths and emergency intensive care admissions in Australia and New Zealand, and the United Kingdom—the ACADEMIA study. Resuscitation 2004;62:275–82. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hillman KM, Bristow PJ, Chey T et al. . Duration of life-threatening antecedents prior to intensive care admission. Intensive Care Med 2002;28:1629–34. 10.1007/s00134-002-1496-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing 2006;35:350–64. 10.1093/ageing/afl005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewis LM, Miller DK, Morley JE et al. . Unrecognized delirium in ED geriatric patients. Am J Emerg Med 1995;13:142–5. 10.1016/0735-6757(95)90080-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:248–53. 10.1067/mem.2002.122057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Terrell KM, Hustey FM, Hwang U et al. . Quality indicators for geriatric emergency care. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:441–9. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N et al. . The course of delirium in older medical inpatients: a prospective study. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:696–704. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20602.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han JH, Wilson A, Vasilevskis EE et al. . Diagnosing delirium in older emergency department patients: validity and reliability of the delirium triage screen and the Brief Confusion Assessment Method. Ann Emerg Med 2013;62:457–65. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]