Abstract

Objectives

Waterpipe smoking is highly prevalent among university students, and has been increasing in popularity despite mounting evidence showing it is harmful to health. The aim of this study was to measure preferences for waterpipe smoking and determine which product characteristics are most important to smokers.

Setting

A large university in the Southeastern USA.

Participants

Adult waterpipe smokers attending the university (N=367).

Design

Participants completed an Internet-based discrete choice experiment to reveal their preferences for, and trade-offs between, the attributes of hypothetical waterpipe smoking sessions. Participants were presented with waterpipe lounge menus, each with three fruit-flavoured options and one tobacco flavoured option, in addition to an opt out option. Nicotine content and price were provided for each choice. Participants were randomised to either receive menus with a text-only health-warning message or no message.

Outcome measures

Multinomial and nested logit models were used to estimate the impact on consumer choice of attributes and between-subject assignment of health warnings respectively.

Results

On average, participants preferred fruit-flavoured varieties to tobacco flavour. They were averse to options labelled with higher nicotine content. Females and non-smokers of cigarettes were more likely than their counterparts to prefer flavoured and nicotine-free varieties. Participants exposed to a health warning were more likely to opt out.

Conclusions

Fruit-flavoured tobacco and lower nicotine content labels, two strategies widely used by the industry, increase the demand for waterpipe smoking among young adults. Waterpipe-specific regulation should limit the availability of flavoured waterpipe tobacco and require accurate labelling of constituents. Waterpipe-specific tobacco control regulation, along with research to inform policy, is required to curb this emerging public health threat.

Keywords: HEALTH ECONOMICS, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to elicit preferences for waterpipe smoking using the discrete choice experiment method.

Fruit-flavoured tobacco and lower nicotine content labels both increase the demand for waterpipe smoking among young adults.

Participants who were randomised to see waterpipe-specific health warnings on their menus were significantly more likely to opt out of choosing a waterpipe product.

The study was limited to a convenience sample from a large US-based university and findings may not be generalisable.

Introduction

Waterpipe smoking is a form of tobacco consumption that originated in the Middle East some five centuries ago and has recently experienced a worldwide resurgence.1 Even in Western societies that have achieved significant progress in curbing the prevalence of cigarette smoking, waterpipe smoking has been steadily gaining in popularity.2 In the USA, as in several Western countries, the highest prevalence of waterpipe smoking is among young adults, including university-aged students, of whom approximately one-third have ever smoked waterpipe tobacco.3 4

Despite the mounting evidence concerning the health risks and nicotine dependence associated with waterpipe smoking,5 it remains largely unregulated worldwide.6 There are several major challenges to waterpipe regulation. Whereas the cigarette market is dominated by a small number of multinationals, the waterpipe industry is characterised by a large number of producers, importers and manufacturers of tobacco and accessories. Waterpipe smoking products exhibit unique features when compared to cigarettes, including the use of charcoal to burn the tobacco, a smoking apparatus that varies in shape and size, and a wide array of tobacco flavours and packaging.

Current tobacco control policies are not clear about health warning requirements for the waterpipe. This is particularly important considering that those who smoke at waterpipe serving establishments do not routinely view waterpipe tobacco packages. For example, in 2011, Gulf Cooperation Council countries adopted standards for labelling of tobacco products, including pictorial health warnings specific to waterpipe tobacco, covering 50% of the front and back of the package.7 Even so, health warning labels on existing waterpipe tobacco are not evidence based, and waterpipe tobacco packets display a variety of deliberately misleading features, including incorrect labelling of constituents.8

The WHO has recently emphasised the need for research that examines ‘the extent to which flavoured tobacco, waterpipe cafés, and other marketing tools, economic factors and the absence of waterpipe-specific tobacco regulation influence the global spread of waterpipe tobacco smoking’.9 While flavour availability has been identified as a potential factor in attracting new smokers, especially youth and women,10 no empirical evidence exists that examines the influence of flavours on the demand for waterpipe tobacco smoking. The inaccurate labelling of waterpipe tobacco products,8 including waterpipe café menus, has been documented but the extent that this mislabelling influences waterpipe smoking has not been examined. Further, health warning labels have been shown to be effective in educating smokers about the harmful effects of cigarettes11 but have not been tested among waterpipe smokers.12

One approach that is well suited for measuring the influence of product characteristics on consumer choices is the discrete choice experiment (DCE).13 14 The basic premise of a DCE is that demand for a product, such as a waterpipe, can be explained using a set of product attributes and DCEs are commonly used in marketing research to test the influence of individual product attributes simultaneously. Respondents are given various sets of hypothetical situations in which they must choose between several alternatives. This methodology has recently been used by tobacco control researchers to assess patient preferences for competing smoking cessation strategies.15 16

In this study, a DCE was used to examine the influence of four waterpipe smoking product characteristics that are typically addressed by tobacco control regulations globally (flavour, nicotine content, price and health warnings) among previous waterpipe users. The study was conducted among university students who have some of the highest prevalence rates of waterpipe smoking in the USA.3

Methods

Theoretical framework

The DCE methodology is derived from the theory of value17 and assumes that individual choice for a product is determined by its characteristics or attributes.18 Random Utility Theory is used to analyse DCEs. The utility function is modelled using a systematic component—since consumers are assumed to know the nature of their utility functions—and a random or unexplained component.19 20 The systematic component in this study was estimated to reveal the relative importance of attributes involved in choosing a waterpipe smoking session. The random component of the utility function measures how changes in attributes affect choices through probabilistic analysis.20 In this study, we estimate the probability of choosing different hypothetical waterpipe product configurations for a smoking session using a waterpipe lounge menu. A price proxy was included in our choice sets in order to estimate willingness to pay, a monetary measure of value typically used in determining the relative ranking of attributes and the trade-offs across attributes.

Survey administration

A purposive convenience sample of students was recruited from the University of South Carolina between June and October 2014. Potential participants were approached in common areas across campus and asked to complete the survey if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) they were at least 18 years old, (2) they were currently attending college or will be attending in the upcoming year and (3) they had smoked at least one or two puffs of waterpipe tobacco at some point in their lives. On consent, participants were provided with an electronic tablet to access the Internet-based survey. To incentivise participation, respondents were given $10 on completion of the survey. A total of 525 students were identified, of whom 367 completed the survey (response rate=69.9%). The final survey included the DCE, in addition to questions assessing basic demographic characteristics—age, gender, class standing, race/ethnicity and cigarette smoking status. The study protocol was approved by the University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Development of the discrete choice experiment

The selection of attributes used in the experiment was guided by factors expected to affect respondents’ choices when presented with a waterpipe menu, as well as by policy-relevant attributes.6 These attributes included flavour, nicotine content and price. The levels of nicotine content were selected based on prior studies documenting common labelling of ingredients on current waterpipe tobacco packages.8 12

The four levels for flavour were Double Apple, Blue Mist, Pirate's Cave and tobacco flavour (non-flavoured). The three fruit flavours were chosen based on popularity in the US market as reported by an Internet-based retailer.21 We included three levels of nicotine content 0.0% (nicotine-free), 0.05% and 0.5%. Many waterpipe tobacco packages are labelled as containing 0.05% nicotine for washed tobacco and 0.5% nicotine for unwashed tobacco, which may be confusing to consumers because no information is provided that details how these percentages were calculated and how they apply to their selected product.8 Meanwhile, the nicotine-free level was chosen to represent commonly consumed herbal waterpipe varieties.22 Three levels were chosen for the price of a session to be reflective of realistic price options: $5, $10 and $20. The design produced a total of 4×3×3 (36) potential profiles. The selected fractional factorial design included 18 distinct choice sets that were divided into two blocks of nine choice sets. All menus (choice sets) within the first block included health warning messages, and the menus from the second block did not include health warnings. Respondents were then randomly assigned to one of the two blocks. The health warning message used was tailored from a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended warning message for cigarettes in the USA, by replacing the term ‘cigarette’ with ‘hookah’: “WARNING: Waterpipe tobacco smoking causes fatal lung disease”. A sample choice set is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Discrete choice experiment: Sample choice set*. *Attributes and levels: Flavour (Double Apple, Blue Mist, Pirate's Cave, Non-flavoured); Nicotine content (0.0%, 0.05%, 0.5%); Price ($5, $10, $20).

Statistical analysis

Percentages were calculated for categorical variables, and means and SDs for continuous variables. For the DCE, we took each choice between five-way options (four waterpipe products and an opt out option to not select any product) as a specific observation. Hence each respondent provided a maximum of 45 observations. We used multinomial logit regression to analyse the effect of product attributes on consumer choice. Parameter estimates for attribute levels were effect coded in relation to the grand mean, as opposed to a coded reference level. As such, positive values indicate greater preference for a given attribute level and negative values indicate less preference for a given attribute level. In each model, the choice among alternatives depended on the three attributes: flavour, price and nicotine content. We calculated the willingness to pay for marginal changes in nicotine level and for each waterpipe flavour relative to tobacco flavour (non-flavoured). These estimates were calculated as the ratio of the coefficient of interest to the negative of the coefficient on price. We used a nested logit model to analyse both the influence of the product's characteristics on choice and the impact of exposure to a health warning on the propensity to choose a waterpipe smoking session. To assess the influence of each attribute as a whole on consumer choice, a utility range for each attribute was calculated as the difference between the smallest and largest parameter estimates. The relative importance of each attribute was then calculated with respect to the sum of utility ranges. To estimate scaled preferences for waterpipe smoking attributes by respondent characteristics, we estimated additional multinomial logit models with interactions by gender (ie, female vs male) and cigarette smoking status (ie, smoker vs non-smoker). Data analyses were performed in April 2015 using SAS software (V.9.4; SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Sample characteristics

Characteristics of study participants (N=367) are shown in table 1. The mean age of students in the study was 21.9 years (SD, 4 years). One half of the participants (50%) were female, 80% were undergraduates and nearly two-thirds (68%) were non-Hispanic white. Nearly 23% of the sample included concurrent cigarette smokers.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD | 21.9±4.0 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 182 (49.6) |

| Male | 185 (50.4) |

| Class standing | |

| Undergraduate | 295 (80.4) |

| Graduate | 72 (19.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 250 (68.1) |

| Black or African-American | 50 (13.6) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 36 (9.8) |

| Mixed/other race | 19 (5.1) |

| Hispanic | 12 (3.3) |

| Concurrent cigarette user | |

| Yes | 83 (22.6) |

| No | 284 (77.4) |

| Total | 367 (100.0) |

Results of the DCE

Participants were significantly more likely to choose Double Apple and Blue Mist flavours and significantly less likely to choose tobacco flavoured (non-flavoured) waterpipe products (table 2). They were significantly more likely to choose nicotine-free (0.0%) varieties over waterpipe products with higher nicotine content (0.05% and 0.5%), and significantly more likely to choose waterpipe smoking sessions priced at $5 or $10 versus $20. Results of the multinomial logit model with interaction terms indicated differences in consumer preferences across subpopulations, with females showing greater interest in flavoured and nicotine free varieties than that shown by males. Participants who did not currently smoke cigarettes were less interested in tobacco-flavoured and nicotine containing varieties. The nested logit model showed that all three flavoured varieties were preferred to the tobacco flavoured (non-flavoured) choices, and that respondent preferences were significantly associated with lower nicotine and price levels. Assignment to menus with the health warning message, older age of waterpipe smoking initiation and being a non-smoker of cigarettes were all significantly associated with a greater likelihood of choosing the opt out option.

Table 2.

Multinomial and nested logit models of waterpipe smoking preference, and willingness to pay estimates (in USD)

| Multinomial logit coefficient (SE) |

Willingness to pay estimate (CI) |

Nested logit coefficient (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavour | |||

| Double apple | 0.9423 (0.0369)*** | 4.63 (4.11 to 5.23) | 1.3365 (0.4532)** |

| Blue mist | 0.5024 (0.0381)*** | 3.79 (3.31 to 4.29) | 1.1312 (0.3857)** |

| Pirate's cave | 0.0496 (0.0404) | 2.93 (2.49, 3.39) | 0.9041 (0.3106)** |

| Tobacco (Non-flavoured) | −1.4940 (0.0606)*** | Reference | Reference |

| Nicotine content | −0.1837 (0.0640)** | ||

| 0.0% | 0.3116 (0.0304)*** | Reference | |

| 0.05% | −0.0119 (0.0316)*** | −0.82 (−1.02 to −0.63) | |

| 0.5% | −0.1927 (0.0317)*** | −0.96 (−1.18 to −0.74) | |

| Price | −0.3768 (0.1230)** | ||

| $5 | 0.4631 (0.0302)*** | ||

| $10 | 0.1715 (0.0309)*** | ||

| $20 | −0.6346 (0.0345)*** | ||

| Opt out choice | |||

| Health warning exposure | 0.2803 (0.1252)* | ||

| Age at waterpipe initiation | 0.1046 (0.0222)*** | ||

| Non-cigarette smoker | 1.1758 (0.2279)*** | ||

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

CI: 95% Krinsky-Robb CIs.

Relative importance of attributes

The relative importance of product attributes in predicting choice of a waterpipe smoking session reflects the relative weight that consumers placed on independent product characteristics when forming their choices. Attributes that have a stronger positive or negative impact on utility carry a greater relative weight. Overall, flavour accounted for almost two-thirds (65%) of the waterpipe smoking decision, followed by price (22%) and nicotine content (13%).

Variation across subgroups

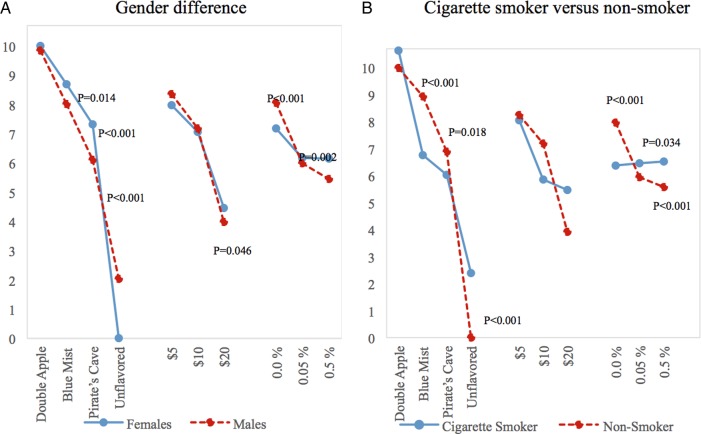

To explore whether the heterogeneity observed in table 2 is explained by differences in gender and cigarette smoking status, we estimated additional multinomial logit models that included interactions between attribute levels and gender (figure 2A), and cigarette smoking status (figure 2B). Compared with males, females were more likely to prefer Blue Mist and Pirate's Cave flavours and less likely to prefer tobacco flavour (non-flavoured). Females were also more likely than males to prefer nicotine-free (0.0%) waterpipe products and less likely to prefer products with the highest nicotine level (ie, 0.5%). When examining preferences by cigarette smoking status, non-smokers were more likely to prefer all flavoured varieties and less likely to prefer tobacco flavoured (non-flavoured) waterpipe products compared with smokers. Non-smokers were also more likely to prefer nicotine-free (0.0%) and less likely to prefer products with higher nicotine levels than were cigarette smokers.

Figure 2.

Scaled estimates of waterpipe smoking preferences by gender and cigarette smoking status*. (Panel A): Gender Difference. (Panel B): Cigarette Smoker versus Non-smoker. *Estimates of the effect of each attribute level on waterpipe smoking preferences, stratified by gender (Panel A) and cigarette smoking status (Panel B). Models included correlated random main effects and fixed interactions between attribute levels and gender/cigarette smoking status. p Values indicate statistically significant differences between the respective groups, as measured by the interaction terms. Coefficients were scaled to range from 0 to 10.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to elicit preferences for waterpipe smoking using the DCE method. While prior research may have provided limited evidence on the determinants of waterpipe smoking when examined independently, the DCE tests the relative influence on choice of multiple attributes. This method is useful because it provides insight into forecasting the relative effect of different policy options. The results show that fruit-flavoured tobacco and lower nicotine content labels, two strategies widely used by the industry, may increase the demand for waterpipe smoking among young adults who have tried waterpipe, while waterpipe-specific health warnings may be effective at deterring smoking behaviour. The study findings also reveal heterogeneity in preferences for waterpipe smoking by gender and cigarette smoking status. These estimates can provide the first tangible targets for intervention and regulatory strategies to curb waterpipe smoking.

Among the three attributes and across the levels evaluated, the flavour attribute had the strongest influence on preferences, with fruit flavoured waterpipe products, on average, preferred to tobacco flavoured (non-flavoured) products. This effect was stronger among females (vs males) and non-smokers of cigarettes (vs cigarette smokers). This finding supports the proposition that flavours can lure women and non-smokers into waterpipe initiation.23 As such, targeting flavoured waterpipe tobacco can be an effective first step for regulatory effort to curb its use.

Price was the second most important attribute for influencing product preferences. Inclusion of price as a DCE attribute creates a more realistic market scenario for the participant and allows for the calculation of willingness-to-pay estimates for other attributes. Overall, consumers were more likely to choose less expensive waterpipe products. This is consistent with the behaviour of cigarette smokers, for whom demand is significantly reduced with higher prices.24 Price-based policies and taxation therefore represent viable options for an effective waterpipe regulatory framework.

The third attribute strongly associated with preferences is nicotine level. On average, participants preferred waterpipe products labelled as nicotine-free versus nicotine containing options. However, preferences for nicotine differed by gender and cigarette smoking status, with females and non-smokers of cigarettes more likely to choose nicotine-free products, compared with males and cigarette smokers, respectively. This may help explain why waterpipe tobacco manufacturers mislabel their products as containing low levels of nicotine,8 and calls for stricter regulations on labelling practices for waterpipe tobacco products. This issue is also relevant to current discussions about reducing nicotine levels in cigarettes, which may increase the appeal of tobacco to non-smokers.25 26

Participants who were randomised to see waterpipe-specific health warnings on their menus were significantly more likely to opt out of choosing a waterpipe product. This is consistent with the effectiveness of health warning labels in decreasing the demand for cigarettes and suggests that health warnings containing information about the harmful effects of waterpipe smoking may help discourage this behaviour.

Waterpipe smokers who participated in this study indicated their willingness to make certain trade-offs when choosing a waterpipe smoking session. The study design was based on a convenience sample, and no systematic attempts were made to regulate sampling factors such as time of day, day of the week and location. As such, findings may not be generalisable to a broader population, including those who have never tried waterpipe smoking. The study design did not include random ordering of flavour options within each choice set, which may have influenced the choice of a flavoured option over the non-flavoured option. The selected trade-offs were based on hypothetical scenarios and should be treated with caution because smokers may have indicated different preferences if actual waterpipe lounge menus had been presented to them, where the choices they made involved monetary exchange for and use of the product. Given that DCEs depend on responses to hypothetical scenarios, it is important to test the external validity of results using revealed preferences from subsequent evaluation of policies and interventions.13 Nonetheless, DCE is an established marketing methodology that enables the measurement of effects on consumer choice from multiple attributes simultaneously. The DCE in this study was selected based on a statistically efficient design with orthogonal and balanced choice sets. Further, presentation of waterpipe smoking session options within menus sought to emulate the experience of product selection for someone who visited a waterpipe lounge, where many users smoke waterpipe products.

The study results provide the first guidance for a regulatory framework to curb waterpipe smoking. Promising components of such a framework can include banning the use of flavoured tobacco, price increases on waterpipe products, accurate labelling of constituents and mandating health warning labels on waterpipe packets and café menus. Further research is needed to study these domains in greater depth, to assess potential trial among non-smokers and to gauge the effects of waterpipe-specific health warning labels, including different types of content and placement on waterpipe devices and products. In this study, we present policy guidance that is relevant to tobacco control efforts and the first of its kind to use a novel experimental approach to understand waterpipe smoking choices among young adults.

Footnotes

Contributors: RGS and JFT were responsible for conception. All the authors contributed to the design of the study. RGS, FI and XC were responsible for the data analysis reported in this paper. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings, contributed to successive drafts and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: RGS was supported by the Office of the Vice President for Research at the University of South Carolina (ASPIRE Programme) grant 35849. WM is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant R01 DA035160. The funding sources had no involvement in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in writing the manuscript and decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was cleared for ethics by the University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data are available by emailing rsalloum@ufl.edu.

References

- 1.Maziak W, Taleb ZB, Bahelah R et al. The global epidemiology of waterpipe smoking. Tob Control 2015;24(Suppl 1):i3–12. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salloum RG, Osman A, Maziak W et al. How popular is waterpipe tobacco smoking? Findings from internet search queries. Tob Control 2015;24:509–13. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salloum RG, Thrasher JF, Kates FR et al. Water pipe tobacco smoking in the United States: findings from the National Adult Tobacco Survey. Prev Med 2015;71:88–93. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haider MR, Salloum RG, Islam F et al. Factors associated with smoking frequency among current waterpipe smokers in the United States: findings from the National College Health Assessment II. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;153:359–63. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Zaatari ZM, Chami HA, Zaatari GS. Health effects associated with waterpipe smoking. Tob Control 2015;24(Suppl 1):i31–43. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jawad M, El Kadi L, Mugharbil S et al. Waterpipe tobacco smoking legislation and policy enactment: a global analysis. Tob Control 2015;24(Suppl 1):i60–5. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammond D.2015. Tobacco Labelling Resource Center. Secondary Tobacco Labelling Resource Center. http://www.tobaccolabels.ca.

- 8.Vansickel AR, Shihadeh A, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco products: nicotine labelling versus nicotine delivery. Tob Control 2012;21:377–9. 10.1136/tc.2010.042416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization, & WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation. Advisory note: waterpipe tobacco smoking: health effects, research needs and recommended actions by regulators–2nd ed. World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward KD et al. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. Samples. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10:393–8. 10.1080/14622200701825023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R et al. Text and graphic warnings on cigarette packages: findings from the international tobacco control four country study. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:202–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakkash R, Khalil J. Health warning labelling practices on narghile (shisha, hookah) waterpipe tobacco products and related accessories. Tob Control 2010;19:235–9. 10.1136/tc.2009.031773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ 2012;21:145–72. 10.1002/hec.1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH. Applied choice analysis: a primer. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salloum RG, Abbyad CW, Kohler RE et al. Assessing preferences for a university-based smoking cessation program in Lebanon: a discrete choice experiment. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:580–5. 10.1093/ntr/ntu188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marti J. Assessing preferences for improved smoking cessation medications: a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Health Econ 2012;13:533–48. 10.1007/s10198-011-0333-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lancaster K. A new approach to consumer theory. J Polit Econ 1966;74:132–57. 10.1086/259131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M. Using discrete choice experiments to value health and health care. Springer Academic Publishers, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McFadden D. The choice theory approach to market research. Market Sci 1986;5:275–9. 10.1287/mksc.5.4.275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda A, Ryan M, van Niekerk R et al. Improving the public health sector in South Africa: eliciting public preferences using a discrete choice experiment. Health Policy Plan 2014;30:600–11. 10.1093/heapol/czu038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.HOOKAH-SHISHA.com. Top 10 Hookah Flavors of All Time. Secondary Top 10 Hookah Flavors of All Time 2014. https://www.hookah-shisha.com/hookahlove/17542-top-10-hookah-flavors-of-all-time.html

- 22.Sutfin EL, Song EY, Reboussin BA et al. What are young adults smoking in their hookahs? A latent class analysis of substances smoked. Addict Behav 2014;39:1191–6. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakkash RT, Khalil J, Afifi RA. The rise in narghile (shisha, hookah) waterpipe tobacco smoking: a qualitative study of perceptions of smokers and non smokers. BMC Public Health 2011;11:315 10.1186/1471-2458-11-315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaloupka FJ, Yurekli A, Fong GT. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tob Control 2012;21:172–80. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McRobbie H, Przulj D, Smith KM et al. Complementing the standard multicomponent treatment for smokers with denicotinized cigarettes: a randomized trial. Nicotine Tob Res 2015. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv122 10.1093/ntr/ntv122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose JE. Denicotinized cigarettes: a new tool to combat cigarette addiction? Addiction 2007;102:181–2. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01727.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]