Abstract

Objectives

It is unknown if prenatal exposure to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) increases the risk of low Apgar score in offspring.

Setting

Population-based study using health registers in Denmark.

Participants

We identified all 677 021 singletons born in Denmark from 1997 to 2008 and linked the Apgar score from the Medical Birth Register with information on the women's prescriptions for AEDs during pregnancy from the Danish Register of Medicinal Product Statistics. We used the Danish National Hospital Registry to identify mothers diagnosed with epilepsy before birth of the child. Results were adjusted for smoking and maternal age.

Results

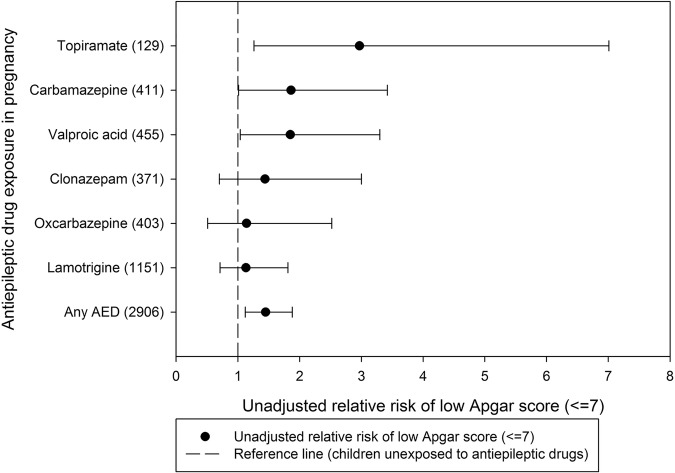

Among 2906 children exposed to AEDs, 55 (1.9%) were born with an Apgar score ≤7 as compared with 8797 (1.3%) children among 674 115 pregnancies unexposed to AEDs (adjusted relative risk (aRR)=1.41 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.85). When analyses were restricted to the 2215 children born of mothers with epilepsy, the aRR of having a low Apgar score associated with AED exposure was 1.34 (95% CI 0.90 to 2.01) When assessing individual AEDs, we found increased, unadjusted RR for exposure to carbamazepine (RR=1.86 (95% CI 1.01 to 3.42)), valproic acid (RR=1.85 (95% CI 1.04 to 3.30)) and topiramate (RR=2.97 (95% CI 1.26 to 7.01)) when compared to unexposed children.

Conclusions

Prenatal exposure to AEDs was associated with increased risk of being born with a low Apgar score, but the absolute risk of a low Apgar score was <2%. Risk associated with individual AEDs indicate that the increased risk is not a class effect, but that there may be particularly high risks of a low Apgar score associated with certain AEDs.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PERINATOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The register study includes singletons with information on Apgar score (N=677 021) born in Denmark from 1997 to 2008.

The Apgar score from the Medical Birth Register was linked with information on women's prescriptions for antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) during pregnancy from the Danish Register of Medicinal Product Statistics.

AED exposure was associated with a 41% increased risk of having a low Apgar score (≤7) (adjusted relative risk (aRR)=1.41 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.85)).

The absolute risk following AED exposure in pregnancy was low (<2%).

AED exposure was based on information from registers and residual confounding may explain part of the increased risk.

Background/rationale

The Apgar score evaluates the clinical state of newborn children in a broad sense based on five physical signs (heart rate, respiratory effort, reflex irritability, muscle tone and colour) present shortly after birth.1 A total score of 10 indicates that the baby is—at that time—in ‘its best possible condition’. The scoring system is an accepted tool for assessing the vitality of newborn infants worldwide,2 3 and the Apgar score measured 5 min after birth is a predictor of neonatal mortality and several neurological outcomes.4–6 Offspring of women with epilepsy7 and offspring of women using antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in pregnancy have been found to have lower Apgar scores compared to offspring of women without epilepsy.7–9 However, a low Apgar score is a rare outcome and associations with AED exposure during pregnancy have been based on a very small number of pregnancies and therefore have had low statistical precision.

Objectives

We studied the risk of low Apgar scores in children prenatally exposed to AEDs in a large cohort of children accounting for confounding factors including epilepsy in the mothers.

Methods

Study design

This is a population-based cohort study based on all singleton live born children in Denmark from 1 February 1997 to 31 December 2008. The study used data from the Danish Civil Registration System, the Danish Medical Birth Registry and the Danish Register of Medicinal Product Statistics.

Setting

Children born in Denmark between 1 February 1997 and 31 December 2008 were identified from the Danish Medical Birth Registry. We used the Danish National Hospital Registry to identify mothers diagnosed with epilepsy before birth of the child. Information from the Danish national health registers was linked through the Danish civil registration number (CPR number) from the Danish Civil Registration System. The Danish civil registration number is a unique identification number given to each citizen living in Denmark ensuring accurate linkage between registers.

Participants and study size

We included all singletons (N=693 838) born in Denmark from 1997 to 2008 excluding those with missing information on Apgar score (n=16 817) leaving 677 021 for analyses. Among these children, 2906 were exposed to AEDs and 674 115 were not exposed to AEDs.

Variables, data sources and measurement

Medication exposure

The Danish Register of Medicinal Product Statistics holds information on all redeemed prescriptions since 1 January 1996. AEDs that are used solely in hospitals are not included in the register. We included information on all redeemed prescriptions from 1 January 1996 to 31 December 2008. The exposure window was defined as 30 days before the estimated day of conception to the day prior to birth. AED exposure was defined as redemption of prescription for medicines with the Anatomical Therapeutic Codes (ATC code) N03A (AEDs) and N05BA09 (clobazam).

Pregnancies exposed to monotherapy were defined as pregnancies where the mothers had redeemed prescriptions for only one type of AED, while pregnancies exposed to polytherapy were defined as pregnancies of mothers who had redeemed prescriptions for more than one type of AED in the exposure window. For both monotherapy and polytherapy, the mothers may also have redeemed prescriptions for other types of medicine during pregnancy. The estimated average daily dose of AEDs was calculated from the total amount of AEDs redeemed during the time from 30 days before pregnancy until birth divided by the number of days in the same time period. On the basis of the defined daily dose (DDD),10 the estimated daily AED dose was dichotomised into high (>50% of DDD) and low (≤50% of DDD).

Epilepsy and psychiatric disease

The Danish National Hospital Registry holds information on inpatients since 1977 and outpatients from 1995. From 1977 to 1993, diagnostic information in the Danish National Hospital Register was based on the International Classification of Diseases, 8th revision (ICD-8), and from 1994 to 2008 on ICD-10. ICD-9 has not been used in Denmark. We used this register to identify mothers diagnosed with epilepsy before birth of the child (ICD-8: 345 and ICD-10: G40 and G41).

The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register was used to identify parents diagnosed with psychiatric disorders before birth of the child (ICD-8: 290–315 and ICD-10: F00.0-F99.9). We specifically looked at mothers with substance abuse (ICD-8: 291, 294.3, 303, 304 and ICD-10: F10-F19) and severe psychiatric disorders (ICD-8: 296.1–296.8, 298.1 and 295 and ICD-10: F30-F31 and F20).

Pregnancy outcomes

The Danish Medical Birth Registry contains data on newborn children including information on gestational age and Apgar score (0–10) at birth (5 min).

Statistical methods

We estimated the relative risk (RR) of low Apgar score using binomial regression with robust variance estimation to allow for correlation between pregnancy outcomes within each woman. RRs of low Apgar score (≤7) were adjusted for maternal age (divided into tertiles) and smoking (yes, no). Singletons with missing information on smoking (n=20 490), maternal age (n=1) and gestational age (n=2230) were excluded from analyses.

When analysing individual drugs, there were too few exposed cases to allow for adjusted estimates. This was also the case for offspring of women without epilepsy when we stratified on epilepsy diagnosis in the mother.

We used multinomial logistic regression to calculate the OR of being born with an Apgar score ≤7 and the OR of being born with an Apgar score of 8–9, compared to being born with an Apgar score of 10.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Bias

Sensitivity analyses

To minimise confounding by indication, we stratified the main analyses for mothers ever having a diagnosis of epilepsy identified in the Danish National Hospital Register (ie, from 1977). In further analyses, we stratified for having a diagnosis of epilepsy during the 5 years before conception of the index pregnancy.

In sensitivity analyses, we excluded women exposed to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and insulin and insulin analogues (ATC codes: N05A, N06A and A10A).

We analysed the risk after extending the exposure period from 30 before pregnancy to 180 days before pregnancy, and we analysed the risk after excluding from the control group women who had been exposed to AED from 180 days before pregnancy to 30 days before pregnancy but not during the index pregnancy.

We restricted the cohort to include families with at least two full siblings and with at least one of the siblings being born with a low Apgar score. The association with AED exposure in the paired data was analysed using conditional logistic regression.

Results

Participants and descriptive data

Out of the 677 021 singletons, 8852 (1.3%) were born with an Apgar score ≤7. Characteristics of study participants are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (monotherapy and polytherapy combined)

| Characteristics | Exposed to AED N=2906 |

Not exposed to AED N=674 115 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 780 | (26.8) | 125 863 | (18.7) |

| No | 1981 | (68.2) | 527 907 | (78.3) |

| Missing | 145 | (5.0) | 20 345 | (3.0) |

| Maternal age (years) | ||||

| <21 | 83 | (2.9) | 17 991 | (2.7) |

| 21–25 | 476 | (16.4) | 102 276 | (15.2) |

| 26–30 | 1044 | (35.9) | 257 147 | (38.1) |

| 31–35 | 895 | (30.8) | 214 628 | (31.8) |

| ≥36 | 408 | (14.0) | 82 072 | (12.2) |

| Missing | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.0) |

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | 1367 | (47.0) | 288 334 | (42.8) |

| ≥1 | 1538 | (52.9) | 385 402 | (57.2) |

| Missing | 1 | (0.0) | 379 | (0.1) |

| Cohabitation | ||||

| Yes | 2222 | (76.5) | 553 987 | (82.2) |

| No | 670 | (23.1) | 114 150 | (16.9) |

| Missing | 14 | (0.5) | 5978 | (0.9) |

| Income (%)* | ||||

| 0–19 | 624 | (21.5) | 118 703 | (17.6) |

| 20–39 | 805 | (27.7) | 134 876 | (20.0) |

| 40–59 | 600 | (20.6) | 139 171 | (20.6) |

| 60–79 | 510 | (17.5) | 141 922 | (21.1) |

| 80–100 | 367 | (12.6) | 138 736 | (20.6) |

| Missing | 0 | (0.0) | 707 | (0.1) |

| Maternal education (years) | ||||

| <10 | 411 | (14.1) | 57 956 | (8.6) |

| 10–12 | 1066 | (36.7) | 197 633 | (29.3) |

| >12 | 1365 | (47.0) | 402 117 | (59.7) |

| Missing | 64 | (2.2) | 16 409 | (2.4) |

| Substance abuse | ||||

| Yes | 106 | (3.6) | 2284 | (0.3) |

| No | 2800 | (96.4) | 671 831 | (99.7) |

| Missing | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

*The annual income was divided into quintiles (0–19%, 20–39%, 40–59%, 60–79%, 80–100%).

AED, antiepileptic drug.

Main results

After adjustment for smoking and maternal age, children of women using AED during pregnancy (N=2906) had an adjusted RR of 1.41 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.85) of having a low Apgar at 5 min (≤7) when compared to children of women who did not use AEDs during pregnancy (table 2). We also estimated the risk of a low Apgar score with additional adjustment for gestational age and found an almost unchanged adjusted relative risk (aRR) of 1.38 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.82).

Table 2.

Apgar score (≤7) in AED exposed and unexposed children (monotherapy and polytherapy combined)

| AED exposure | N (%) | Apgar score ≤7, n (%) | Apgar score >7, n (%) | Relative risk crude, (95% CI) | Relative risk, adjusted* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 2906 (100) | 55 (1.9) | 2851 (98.1) | 1.45 (1.12 to 1.88) | 1.41 (1.07 to 1.85) |

| No | 674 115 (100) | 8797 (1.3) | 665 318 (98.7) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

*Apgar score was adjusted for maternal age and smoking.

AED, antiepileptic drug.

We analysed the adjusted OR (aOR) of being born with an Apgar score ≤7 (aOR=1.47 (95% CI 1.10 to 1.94)) and the aOR of being born with an Apgar score of 8–9 (aOR=1.59 (95% CI 1.49 to 1.81)) compared to being born with an Apgar score of 10 (see online supplementary etable 1).

When stratified on the mothers’ epilepsy diagnosis prior to birth, the unadjusted RR of having a low Apgar score following AED exposure was increased by 34% in offspring of women with epilepsy (RR=1.34 (95% CI 0.90 to 2.01)) (table 3). There were too few cases to estimate the adjusted risk in offspring of mothers without an epilepsy diagnosis, but the unadjusted estimate was 77% increased (RR=1.77 (95% CI 1.09 to 2.88)) (table 3).

Table 3.

Relative risk for low Apgar score (≤7) in AED exposed and unexposed children stratified on mother's diagnosis of epilepsy (monotherapy and polytherapy combined)

| Epilepsy | AED | N (%) | Apgar score ≤7, n (%) | Apgar score >7, n (%) | Relative risk, crude (95% CI) | Relative risk, adjusted* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Yes | 2215 (100) | 39 (1.8) | 2176 (98.2) | 1.38 (0.94 to 2.04) | 1.34 (0.90 to 2.01) |

| No | 5261 (100) | 67 (1.3) | 5194 (98.7) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| No | Yes | 691 (100) | 16 (2.3) | 675 (97.7) | 1.77 (1.09 to 2.88) | NA (–) |

| No | 668 854 (100) | 8730 (1.3) | 660 124 (98.7) | 1.00 (reference) | NA (–) |

*Apgar score was adjusted for smoking.

AED, antiepileptic drug; NA, not applicable.

We found that the crude RRs were increased for all types of AEDs, although the estimates reached statistical significance only for use of carbamazepine, valproic acid and topiramate exposure (table 4 and figure 1). When we restricted the analyses to children exposed to monotherapy, there was no increased risk associated with lamotrigine exposure and only exposure to carbamazepine was significantly increased compared to unexposed children (see online supplementary etable 2 and efigure 1). Owing to a low number of exposed cases with a low Apgar score (<5), it was not possible to assess the risk associated with topiramate and oxcarbazepine monotherapy exposure in pregnancy.

Table 4.

Unadjusted relative risk of low Apgar score (≤7) by AED exposure during pregnancy (monotherapy and polytherapy combined)

| AED | Apgar >7, n (%) | Apgar ≤7, n (%) | Relative risk*, (crude) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clonazepam | 364 (98.1) | 7 (1.9) | 1.44 (0.70 to 3.00) |

| Carbamazepine | 401 (97.6) | 10 (2.4) | 1.86 (1.01 to 3.42) |

| Oxcarbazepine | 397 (98.5) | 6 (1.5) | 1.14 (0.51 to 2.52) |

| Valproic acid | 444 (97.6) | 11 (2.4) | 1.85 (1.04 to 3.30) |

| Lamotrigine | 1134 (98.5) | 17 (1.5) | 1.13 (0.71 to 1.81) |

| Topiramate | 124 (96.1) | 5 (3.9) | 2.97 (1.26 to 7.01) |

| Any AED | 2851 (98.1) | 55 (1.9) | 1.45 (1.12 to 1.88) |

| No AED | 665 318 (98.7) | 8797 (1.3) | 1.00 (reference) |

*Estimates are only presented for AEDs with 5 or more exposed cases.

AED, antiepileptic drug.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted relative risk of low Apgar score (≤7) by antiepileptic drug exposure during pregnancy (monotherapy and polytherapy combined).

We analysed the outcome after exposure to high and low doses of AEDs (monotherapy only). There were 1339 children exposed to high doses of AEDs among whom 19 (1.4%) had a low Apgar score, and 1164 children were exposed to low doses of AEDs among whom 25 (2.2%) had a low Apgar score. The unadjusted RR associated with high AED drug dose was 1.10 (95% CI 0.71 to 1.72) and the unadjusted RR associated with low AED dose was 1.68 (95% CI 1.14 to 2.48) when compared to unexposed children (comparison of RR for high dose with low dose; p=0.16).

We analysed the outcome after exposure to monotherapy and polytherapy of AEDs. There were 2459 children exposed to AED monotherapy among whom 44 (1.79%) had a low Apgar score, and 447 children were exposed to AED polytherapy of whom 11 (2.46%) had a low Apgar score. The aRR (adjusted for smoking and maternal age) associated with AED monotherapy was 1.36 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.85) and the aRR associated with AED polytherapy was 1.65 (95% CI 0.87 to 3.14) when compared to unexposed children (comparison of aRR for monotherapy with polytherapy; p=0.60).

Other analyses

Sibling analyses

For sibling pairs discordant for low Apgar score and AED use (18 women with a total of 50 birth outcomes), the OR of being born with a low Apgar score for those with AED exposure was 1.21 (95% CI 0.50 to 2.96).

Sensitivity analyses

After excluding 16 090 women exposed to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and insulin and insulin analogues, the risk of low Apgar score associated with AED exposure was almost identical to the results of the overall analysis (aRR: 1.46 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.96)).

We excluded 1343 women with severe mental disorders from the analysis, which attenuated the association with prenatal AED exposure to aRR: 1.34 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.79).

We analysed the risk after extending the exposure period from 30 days before pregnancy to 180 days before pregnancy, which slightly attenuated the risk of low Apgar score associated with AED exposure (RR: 1.29 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.68)). After excluding from the control group 584 pregnancies exposed to AED from 180 days before pregnancy to 30 days before pregnancy, but not during the index pregnancy, the estimate of a low Apgar score was almost identical to the overall analysis (aRR: 1.41 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.85)).

We stratified the main analyses for mothers having a diagnosis of epilepsy during the 5 years before conception of the index pregnancy. The adjusted RR of a low Apgar score was 1.22 (95% CI 0.73 to 2.05) for women diagnosed with epilepsy within 5 years of birth. For women without an epilepsy diagnosis, it was not possible to calculate the adjusted RR of low Apgar, but the unadjusted RR for a low Apgar score was 1.92 (95% CI 1.23 to 2.99) for women without an epilepsy diagnosis within 5 years of birth.

Discussion

Key results

AED exposure in pregnancy was associated with an elevated risk of being born with a low Apgar score (≤7), although the absolute risk was low (<2%).

There are only few studies of Apgar score at birth following exposure to AEDs in pregnancy. A multicentre study across 25 centres in the USA and the UK of the neurodevelopmental effects of antiepileptic drugs study found no difference in risk of low 5 min Apgar score when comparing the risk in offspring of women who used carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin and valproate.8 A Finnish register study found no risk of low 5 min. Apgar score associated with overall AED therapy in offspring of women with epilepsy,7 but a more than doubling of the risk associated with valproate exposure. We found increased risks of low Apgar score at 5 min. following carbamazepine, valproic acid and topiramate exposure, but the number of exposed cases was low.

We also found that AED exposure in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for the less severe outcome (ie, Apgar score 8–9). An Apgar score of 8–9 has also been associated with adverse outcome in the affected children.6

Limitations

Even though we studied almost 3000 exposed pregnancies, only 2% of children exposed to AEDs were born with an Apgar score ≤7, and in a large number of analyses it was not possible to adjust the risk estimates for potential confounders. Therefore, unadjusted residual confounding may account for some of the risk associated with AED exposure.

Adjusting for gestational age had almost no effect on the association between AED exposure in pregnancy and risk of low Apgar score in the offspring. AED exposure in pregnancy was not associated with preterm birth in a recent study from Denmark,11 and prior to study onset it was decided to focus on two well-established confounders, namely smoking in pregnancy and maternal age.12 13 In addition, low gestational age following AED exposure may lie on the causal pathway between AED exposure and low Apgar score and therefore should not necessarily be adjusted for.14

The Apgar score was registered at birth with some measurement error, and at that point of time, the use of AEDs in pregnancy would have been known. However, we have no reason to believe that allocation of a specific Apgar score was influenced by the knowledge of the AED exposure during pregnancy.

The study was based on redeemed prescriptions which for AEDs are a good estimator of compliance with AED use.15 However, the exposure window was based on the time point when the women redeemed a prescription and not on when they actually ingested the tablets; therefore, misclassification of timing of the exposure may have occurred. We therefore did not analyse the risk of low Apgar score by exposure trimester. Since the timing of exposure is not precise, it was not possible to discriminate between sequential monotherapy (ie, switching from one AED to another AED without overlap) and polytherapy (two AEDs taken concomitantly), and both groups were included as polytherapy. The children exposed to polytherapy may thus in reality have been exposed to sequential monotherapy, although switching between AEDs without overlap is probably not common.

We were unable to identify a difference in risk of low Apgar score between children exposed to high dose and low dose of AEDs in pregnancy.16 17 However, our estimate of drug dose is based on the reimbursement rate in pregnancy and thus is most likely an imprecise measure of drug dose in pregnancy. Given the low number of exposed cases within individual AEDs, it was not possible to compare high dose with low dose within individual AEDs.

We analysed all singletons born in Denmark, and loss to follow-up is very unlikely in this study.

Interpretation and generalisability

Low Apgar score at 5 min has been associated with increased risk of subsequent death,18 cancer,19 epilepsy4 6 or neurological disability,18 20 and is thus an important outcome to consider when evaluating the risks in pregnancy. However, the majority of surviving babies with low Apgar scores grow up without disability, which should also be taken into account when evaluating the risks of AED treatment in pregnancy.

Conclusion

Prenatal exposure to AEDs was associated with a 41% increased RR of low Apgar score, but the absolute risk was low (<2%) and may be partly be explained by confounding by indication.

Footnotes

Contributors: JC, HP, MISK, ETP, MV, MJS, JO, BHB and LHP initiated the study, obtained funding, designed the study, interpreted the results, revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript; they had access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. MISK constructed the population. HP analysed the data. JC wrote the first draft.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Jakob Christensen receives research support from the Danish Epilepsy Association. Lars Henning Pedersen is supported by a Sapere Aude–Postdoc grant from the Danish Council for Independent Research. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: JC reported receiving honoraria for serving on the scientific advisory boards of UCB Nordic and Eisai AB; receiving lecture honoraria from UCB Nordic and Eisai AB; and receiving travel funding from UCB Nordic.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Supplementary etable 2 and efigure 1 are available online.

References

- 1.APGAR V. A proposal for a new method of evaluation of the newborn infant. Curr Res Anesth Analg 1953;32:260–7. 10.1213/00000539-195301000-00041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casey BM, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. The continuing value of the Apgar score for the assessment of newborn infants. N Engl J Med 2001;344:467–71. 10.1056/NEJM200102153440701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papile LA. The Apgar score in the 21st century. N Engl J Med 2001;344:519–20. 10.1056/NEJM200102153440709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrenstein V, Sorensen HT, Pedersen L et al. . Apgar score and hospitalization for epilepsy in childhood: a registry-based cohort study. BMC Public Health 2006;6:23 10.1186/1471-2458-6-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harden CL, Meador KJ, Pennell PB et al. . Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy—focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): teratogenesis and perinatal outcomes: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology 2009;73:133–41. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a6b312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Y, Vestergaard M, Pedersen CB et al. . Apgar scores and long-term risk of epilepsy. Epidemiology 2006;17:296–301. 10.1097/01.ede.0000208478.47401.b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Artama M, Gissler M, Malm H et al. . Effects of maternal epilepsy and antiepileptic drug use during pregnancy on perinatal health in offspring: nationwide, retrospective cohort study in Finland. Drug Saf 2013;36:359–69. 10.1007/s40264-013-0052-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pennell PB, Klein AM, Browning N et al. . Differential effects of antiepileptic drugs on neonatal outcomes. Epilepsy Behav 2012;24:449–56. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borthen I, Eide MG, Daltveit AK et al. . Delivery outcome of women with epilepsy: a population-based cohort study. BJOG 2010;117:1537–43. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.2014. WHO ATC code. http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/

- 11.Kilic D, Pedersen H, Kjaersgaard MI et al. . Birth outcomes after prenatal exposure to antiepileptic drugs—a population-based study. Epilepsia 2014;55:1714–21. 10.1111/epi.12758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res 2004;6(Suppl 2):S125–40. 10.1080/14622200410001669187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waldenstrom U, Aasheim V, Nilsen AB et al. . Adverse pregnancy outcomes related to advanced maternal age compared with smoking and being overweight. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:104–12. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothman KJ. Modern epidemiology. Boston: Little, Brown, Cop., 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olesen C, Sondergaard C, Thrane N et al. . Do pregnant women report use of dispensed medications? Epidemiology 2001;12:497–501. 10.1097/00001648-200109000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vajda FJ, O'Brien TJ, Graham JE et al. . Dose dependence of fetal malformations associated with valproate. Neurology 2013;81:999–1003. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a43e81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vajda F, O'Brien T. Valproic acid use in pregnancy and congenital malformations. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1771–2. 10.1056/NEJMc1008255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Grijota M et al. . Association of Apgar score at five minutes with long-term neurologic disability and cognitive function in a prevalence study of Danish conscripts. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:14 10.1186/1471-2393-9-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Cnattingus S, Gissler M et al. . The 5-minute Apgar score as a predictor of childhood cancer: a population-based cohort study in five million children. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Olsen J, Vestergaard M et al. . Low Apgar scores and risk of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr 2011;158:775–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]