Abstract

Objectives

To estimate prevalence and identify sociodemographic risk factors for Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG), Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Treponema pallidum infections in New Caledonia.

Method

A national cross-sectional survey was undertaken using a three-stage random sampling of general practice surgeries and public dispensaries. Participants were included through opportunistic screening and using a systematic step for selection. The study sample was weighted to the general population aged 18–49 years. Prevalence and risk factors were calculated by logistic regression.

Results

CT was the most common sexually transmitted infection, with a prevalence of 9% (95% CI 6.6% to %11.4), followed by NG 3.5% (95% CI 1.9% to 5.1%), previous or latent syphilis 3% (95% CI 1.7% to 4.3%), NG and CT co-infection 2.1% (95% CI 0.8% to 3.3%) and active syphilis 0.4% (95% CI 0.0% to 0.9%). Being from a young age group (18–25 years), being single, having a low level of education and province of residence were all associated with higher prevalence of all three STIs. Being of Melanesian origin was associated with higher prevalence of both CT and NG. There was a significant interaction between ethnic group and province of residence for prevalence of CT. Female gender was associated with higher prevalence of CT.

Conclusions

The prevalence of CT was similar to estimates from other healthcare-based surveys from the Pacific, but higher for NG and lower for active syphilis infection. All sexually transmitted infections estimates were much higher than those found in population-based surveys from Europe and the USA. The sociodemographic risk factors identified in this study will help guide targeted prevention and control strategies in New Caledonia.

Keywords: Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Treponema pallidum, Socio-demographic risk factors, New Caledonia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This healthcare-based survey obtained more accurate prevalence estimates than routinely collected surveillance data or notification system.

This first cross-sectional survey establishes the most valid sexually transmitted infections (STI) prevalence in New Caledonia.

Sociodemographic risk factors for STI in New Caledonia were: age, marital status, level of education, sex, ethnicity and province of residence.

The prevalence estimates and risk factors established in the present study contribute importantly to the regional picture and evidence base for STIs in Pacific Island countries and territories.

Owing to difference in design between the previous New Caledonian STI survey and the present study, a difference or trend in STI prevalence cannot clearly be determined.

As with other cross-sectional surveys, we are not able to infer causality or for some outcomes, temporality.

Introduction

The sexually transmitted infections (STIs) Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG), Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Treponema pallidum (TP) constitute a substantial burden in Europe,1–6 the USA7 8 and several other countries throughout the world.9 Syphilis, which had disappeared in high-income countries, has now re-emerged as a public health issue.10 STIs are now becoming the most common group of notifiable infectious diseases in most countries, reported through clinician-based or laboratory-based sentinel surveillance systems.1 6 11–14

Estimates of prevalence from surveillance data of symptomatic populations and surveys vary considerably. Population-based surveys using random sampling3 15 are rare, but more accurate in establishing prevalence for the general population.5 The majority of prevalence studies were conducted in healthcare settings in which heterogeneity in recruitment methodologies are considerable.5 Estimates from studies based on opportunistic STI testing in healthcare settings, such as antenatal, pregnancy and STI clinics or general practice (GP) surgeries16 and dispensaries, are difficult to compare to estimates from population-based studies, complicating interpretation.5 17

New Caledonia uses a surveillance system with systematic STI notifications including NG, CT and TP.18 Trends of annual incidence and prevalence demonstrate a similar increase in New Caledonia as in neighbouring countries12 and in other parts of the world.3–5 13 14 Only one prevalence study, from 2006, has been conducted on NG, CT and TP infections previously in New Caledonia.19 This study was designed with quota sampling among pregnant women and demonstrated high prevalence CT: 23.7% (95% CI 17.2% to 31.3%), NG: 7.9% (95% CI 4.1% to 13.4%) and TP: 3.3% (95% CI 1.1% to 7.5%) comparable to other Pacific Island Countries and Territories.20–27

The present cross-sectional survey was based on random sampling of GP surgeries and public dispensaries, and on opportunistic STI screening through a systematic step for selection. This study presents the first national probability prevalence estimates and identifies sociodemographic risk factors for NG, CT and TP infections in a reweighted healthcare-based sample related to the general New Caledonian population aged 18–49 years.

Method

In 2011, for assessing the feasibility of a New Caledonian STI survey in adults, a national committee was created with representative health institutions working in New Caledonia. Given the sensitive nature of sexual health issues in New Caledonian society, the committee decided to undertake a healthcare-based study within family physician practices.

Setting and sampling

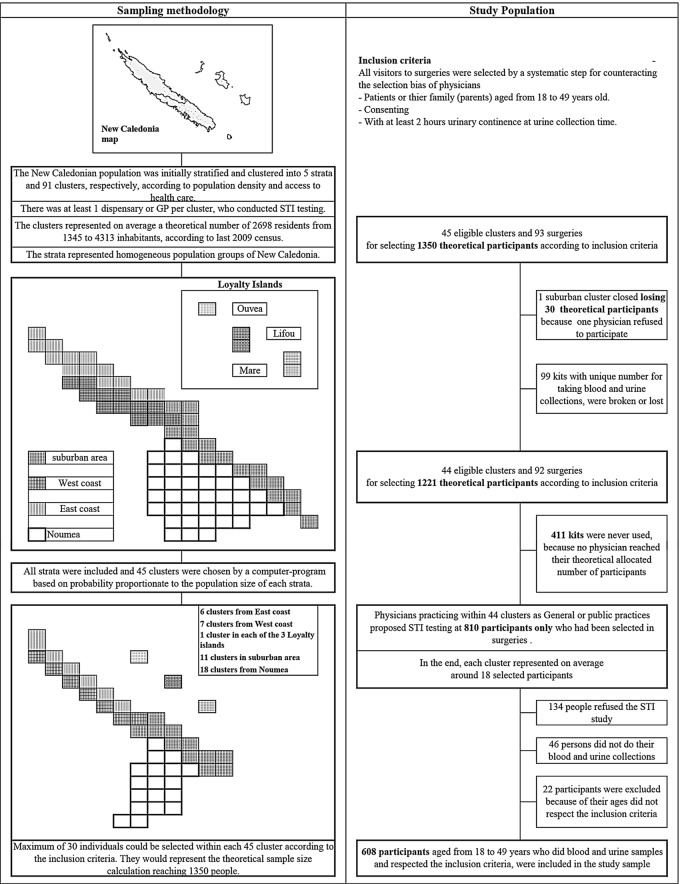

A cross-sectional survey was conducted using random three-stage sampling (figure 1). The primary sampling units were five geographic areas (East and West from the main island, the Loyalty Islands, Noumea and Noumea suburbs), distinct from the three administrative provinces. The strata were formed in collaboration with the national committee. The secondary sampling units or clusters were a subdivision of the five strata. Inside each cluster area, access to care is limited to a given population; one or no more than two or three physicians worked in GP surgeries or public dispensaries. Community clinics were the entry point to the target population. All visitors in these places, patients or their accompanying relatives could be included if consenting and aged 18–49 years. The tertiary sampling units were thus these participants who were selected according to the inclusion criteria. To achieve heterogeneity in the sample population, all strata were selected in the first stage sampling. Then, 45 clusters were randomly selected from the initial five strata built in 91 clusters. Thirty participants per cluster were allocated to one or more physicians in each cluster to increase heterogeneity (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of sampling methodology and study population used in the 2012 STI survey by Agence Sanitaire et Sociale de la Nouvelle-Calédonie (ASSNC). STI, sexually transmitted infections; GP, general practice.

The field officer toured New Caledonia from 15 August to 31 December 2012, explaining the study design to selected physicians, and delivering kits with study forms and sample collection material. Each study form identified the participating patient and physician by a unique code.

To counteract selection bias being introduced by physicians, eligible participants were the first two patients (or relatives of the patient) arriving at GP surgeries or public dispensaries in the morning and afternoon sessions each day during the inclusion period (2 weeks per each study place). In this systematic step for selection, participants were chosen opportunistically and not due to presenting with STI symptoms. If the two first eligible participants of the consultation sessions refused to participate, physicians could not include the following patients.

Written consent was obtained from included patients and sociodemographic variables (gender, age, marital status, study level, province of residence) filled in by GP physicians, including ethnicity (response to: “To which ethnic community do you feel you most belong?”). The different potential risk groups (such as men who have sex with men, or commercial sex workers) were not recorded in the study forms. Blood and urine samples were collected by the physician, private nurse or laboratory, and then analysed at a participating laboratory and reported to the physicians. The coordinating biologist of the partner laboratories’ network centralised the results, and the anonymous study forms plus the laboratory results were sent to the Agence Sanitaire et Sociale de la Nouvelle-Calédonie. A systematic recalling procedure was then initiated among physicians in order to locate any missing patients and data. A database was compiled using Access software.

STI diagnoses

The NG and CT acute infections were detected in urine by PCR tests: the Cobas Amplicor NG Test and the Cobas Amplicor Chlamydiae trachomatis Test (Roche Diagnostics), respectively. To be included, the participant had to have at least 2 h urinary continence at urine collection time. With only one blood sample and no medical history, the antibody kinetics of syphilis of the participants could not be explored. Seroprevalence of syphilis was determined by the treponemal test: Treponema Pallidum Hemagglutinations Assay (TPHA 200 of Bio-rad) and by the non-treponemal test: Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR 500 of Bio-Rad). This was complemented by testing for immunoglobulins-M (IgM) by immunocapture (Captio IgM Capture of Trinity Biotech in collaboration with Cerba laboratory Paris) to distinguish whether syphilis occurred in patients with past, late or latent syphilis or whether syphilis was negative or active.28 Three findings were distinguished: (A) no syphilis: TPHA and VDRL were negative. (B) Early/active syphilis: TPHA (>640) and VDRL (>4) increased markedly or increased slightly with positive IgM. (C) Serological signs of previous or latent syphilis: TPHA and VDRL increased slightly with no IgM.

Sample size

To ensure a largest sample size, a theoretical STI prevalence of 50% was used to calculate a first number of 600 participants.29 The design effect of clustering created an inflation factor estimated at two.30 Around 10% of participants were anticipated to refuse. The theoretical sample size was raised to 1350 individuals after balancing the sample size in different clusters and community clinics.

Statistical methods

The study sample included patients or their accompanying relatives seen in healthcare settings. The study sample (n=608) was weighted to the general population aged 18–49 years according to the latest 2009 census through a raking ratio procedure.31 Links between sociodemographic variables representing explanatory variables were analysed with non-collinear variables added in the logistic models. NG and CT infections and only active syphilis prevalence were studied by binary logistic regression with explanatory variables as independent factors. Tests of interaction were performed. The analyses were conducted with SAS V.9.3 software.

Authorisations

Protocols, including statistical analysis of this study, were approved by the Ethics Committee of New Caledonia, the Advisory Committee on Information Processing in Research of the French health ministry and the National Commission for Computing and Liberties.

Results

Participants

None of the physicians in the 92 GP surgeries or public dispensaries reached their allocated number of participants, and 810 eligible participants were selected. Of these 810 participants, 134 (16.5%) refused, 46 individuals (5.7%) did not provide blood and urine samples and 22 participants were excluded because their ages did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 608 included participants corresponding to 0.5% of the general population aged 18–49 years, estimated at 118 883 in 2009 (figure 1).

Descriptive data: characteristics of study participants and weighting procedure

The distribution of categorical sociodemographic variables did not differ significantly from those of the general population aged 18–49 years according to age group (p=0.99). However, the youngest participants (aged 18, 26, 34 and 42 years) of the four age group classes were systematically overrepresented. The raking ratio procedure was therefore applied with gender, province of residence and linear age for reducing this selection bias (table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of participant characteristics from the 2012 STI survey of Agence Sanitaire et Sociale de la Nouvelle-Calédonie (N=608), adjusted to the general population according to the 2009 census

| General population |

Crude sample |

Weighted sample |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Per cent | n | Per cent | p Value | n | Per cent | |

| Sex* | <0.0001† | ||||||

| Male | 60 117 | 50.57 | 232 | 38.16 | 60 119 | 50.57 | |

| Female | 58 766 | 49.43 | 376 | 61.84 | 58 764 | 49.43 | |

| Total | 118 883 | 100.00 | 608 | 100.00 | 118 883 | 100.00 | |

| Province* | <0.0001† | ||||||

| Loyalty Islands | 7 248 | 6.1 | 70 | 11.51 | 7 252 | 6.1 | |

| North | 22 057 | 18.55 | 157 | 25.82 | 22 053 | 18.55 | |

| South | 89 578 | 75.35 | 381 | 62.66 | 89 578 | 75.35 | |

| Total | 118 883 | 100.00 | 608 | 100.00 | 118 883 | 100.00 | |

| Age group* (years) | 0.9922 | ||||||

| 18–25 | 30 751 | 25.87 | 154 | 25.33 | 33 155 | 27.89 | |

| 26–33 | 29 588 | 24.89 | 154 | 25.33 | 31 209 | 26.25 | |

| 34–41 | 31 877 | 26.81 | 157 | 25.82 | 28 506 | 23.98 | |

| 42–49 | 26 667 | 22.43 | 143 | 23.52 | 26 012 | 21.88 | |

| Total | 118 883 | 100.00 | 608 | 100.00 | 118 883 | 100.00 | |

| Ethnicity | <0.0001† | ||||||

| Melanesian | 49 424 | 41.57 | 282 | 46.38 | 45 254 | 38.07 | |

| Polynesian | 14 643 | 12.32 | 69 | 11.35 | 16 634 | 13.99 | |

| European | 33 998 | 28.6 | 171 | 28.13 | 38 387 | 32.29 | |

| Asian | 4238 | 3.56 | 9 | 1.48 | 2 061 | 1.73 | |

| Mixed race | 15 239 | 12.82 | 66 | 10.85 | 13 916 | 11.71 | |

| ‡ | 1341 | 1.13 | 11 | 1.81 | 2631 | 2.21 | |

| Total | 118 883 | 100.00 | 608 | 100.00 | 118 883 | 100.00 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single | 234 | 38.49 | 48 363 | 40.68 | |||

| In couple | 374 | 61.51 | 70 520 | 59.32 | |||

| Total | 608 | 100.00 | 118 883 | 100.00 | |||

| Study level | |||||||

| Without a diploma | 79 | 12.99 | 15 188 | 12.78 | |||

| Intermediate | 209 | 34.38 | 37 561 | 31.59 | |||

| Bachelor and higher study | 320 | 52.63 | 66 134 | 55.63 | |||

| Total | 608 | 100.00 | 118 883 | 100.00 | |||

*Weighting variables.

‡Non-declared in general population and missing values (n=2 for ethnicity) in sample.

†χ2 Adjustment test p<0.05.

STI, sexually transmitted infections.

Main results

There was a 3.5% (95% CI 1.9% to 5.1%) prevalence of NG, 9.0% (95% CI 6.6% to 11.4%) for CT, 2.1% (95% CI 0.8% to 3.3%) for NG and CT co-infection, 0.4% (95% CI 0.0% to 0.9%) for active syphilis and 3% (95% CI 1.7% to 4.3%) for scar syphilis (tables 2 and 3). There was no significant difference in prevalence of NG for men and women. In contrast, women had a higher prevalence of CT infection, OR 1.3 (95% CI 1.2 to 1.3). Active syphilis was detected only in women, giving 0.9% (95% CI 0.0% to 1.7%) adjusted prevalence for active syphilis among women (tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Prevalence and risk factors associated with Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) infection within the healthcare-based population of New Caledonia aged 18–49 years

| CT infection | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||||||||

| Weighted and adjusted prevalence |

Crude | p Value | Adjusted | p Value | p Value | ||||

| Variables | n Crude | n Weighted | Per cent and (95% CI) |

OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | c | |

| Total prevalence | 56 | 106 830 | 8.99 | (6.56 to 11.41) | |||||

| Sex | <0.0001* | <0.0001† | <00 001† c=0.853 | ||||||

| Male | 18 | 4763.0 | 7.92 | (4.26 to 11.58) | 1.00 (ref) | – | 1.00 (ref) | – | |

| Female | 38 | 5920.0 | 10.07 | (6.91 to 13.24) | 1.30 | 1.25 to 1.35) | 1.28 | (1.22 to 1.34) | |

| Age group (years) | <0.0001† | <0.0001* | |||||||

| 18–25 | 33 | 6202.0 | 18.71 | (12.40 to 25.02) | 56.50 | (46.58 to 68.54) | 52.13 | (42.88 to 63.37) | |

| 26–33 | 16 | 3299.0 | 10.57 | (5.36 to 15.78) | 29.02 | (23.89 to 35.25) | 26.24 | (21.56 to 31.95) | |

| 34–41 | 6 | 1077.0 | 3.78 | (0.60 to 6.95) | 9.64 | (7.89 to 11.78) | 9.89 | (8.08 to 12.11) | |

| 42–49 | 1 | 105.0 | 0.41 | (0.00 to 1.20) | 1.00 (ref) | – | 1.00 (ref) | – | |

| Province | <0.0001* | <0.0001† | |||||||

| Loyalty Islands | 5 | 531.0 | 7.34 | (0.92 to 13.75) | 0.88 | (0.81 to 0.97) | – | – | |

| North | 20 | 2783.0 | 12.62 | (7.24 to 18.00) | 1.61 | (1.54 to 1.69) | – | – | |

| South | 31 | 7369.0 | 8.23 | (5.35 to 11.11) | 1.00 (ref) | – | – | – | |

| Ethnicity‡ | <0.0001* | <0.0001† | |||||||

| Melanesian | 44 | 7937.0 | 17.54 | (12.51 to 22.56) | 5.69 | (5.4 to 5.96) | – | – | |

| Others | 11 | 2556.0 | 3.60 | (1.39 to 5.81) | 1.00 (ref) | – | – | – | |

| Ethnicity/Province | <0.0001† | ||||||||

| Melanesian/Loyalty Islands | 4 | 447.2 | – | – | – | – | 2.68 | (2.57 to 2.79) | |

| Melanesian/North | 19 | 2593.0 | – | – | – | – | 5.74 | (5.55 to 5.93) | |

| Melanesian/South | 21 | 4897.0 | – | – | – | – | 6.64 | (6.58 to 6.70) | |

| Others/Loyalty Islands | 1 | 84.8 | – | – | – | – | 5.70 | (5.48 to 5.95) | |

| Others/North | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Others/South | 10 | 2472.0 | – | – | – | – | 1.00 (ref) | – | |

| Marital status | <0.0001* | <0.0001† | |||||||

| Single | 35 | 6435.0 | 13.31 | (8.82 to 17.79) | 2.39 | (2.30 to 2.49) | 1.82 | (1.73 to 1.90) | |

| In couples | 21 | 4248.0 | 6.02 | (3.37 to 8.68) | 1.00 (ref) | – | 1.00 (ref) | – | |

| Study level | <0.0001ψ | <0.0001* | |||||||

| Without a diploma | 6 | 1179.0 | 7.76 | (1.45 to 14.07) | 0.94 | (0.88 to 1.00) | 1.28 | (1.18 to 1.38) | |

| Intermediate | 24 | 4055.0 | 10.79 | (6.34 to 15.25) | 1.35 | (1.29 to 1.41) | 1.08 | (1.02 to 1.13) | |

| Bachelor and higher study | 26 | 5449.0 | 8.24 | (5.00 to 11.48) | 1.00 (ref) | – | 1.00 (ref) | – | |

*Likelihood ratio test p<0.20.

†Likelihood ratio test p<0.05.

‡1 missing value for ethnicity among a participant with CT.

Table 3.

Total prevalence of syphilis (scar and active infections) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) infection, and risk factors associated with active syphilis only and NG infection within the healthcare-based population of New Caledonia aged 18–49 years

| Active syphilis infection |

NG infection |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||||||||||||

| Variables | n crude | n weighted | weighted and adjusted prevalence |

crude | p Value | adjusted | p Value | p Value | n crude | n weighted | weighted and adjusted prevalence |

crude | p Value | adjusted | p Value | p Value | ||

| % and (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | c | % and (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | c | |||||||

| Total prevalence | ||||||||||||||||||

| Active syphilis | 4 | 498.4 | 0.42 | (0.00 to 0.86) | ||||||||||||||

| NG | 21 | 41 730 | 3.51 | (1.93 to 5.09) | – | |||||||||||||

| Sex | – | – | – | – | – | 0.4312 | – | – | – | |||||||||

| Male | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8 | 2135.0 | 3.55 | (1.04 to 6.06) | 1– | – | – | – | – |

| Female | 4 | 498.4 | 0.85 | (0.00 to 1.73) | – | – | – | – | – | 13 | 2038.0 | 3.47 | (1.55 to 5.38) | 0.98 | (0.92 ; 1.04) | – | – | – |

| Ethnicity* | – | – | – | – | <0.0001† | <0.0001‡ | <0.0001‡ c=0.783 | |||||||||||

| Melanesian | 4 | 498.4 | 1.1 | (0.0 to 2.24) | – | – | – | – | – | 13 | 2139.0 | 4.73 | (2.05 to 7.40) | 4.32 | (3.72 to 5.02) | 4.14 | (3.55–4 to.83) | |

| Polynesian | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 188.8 | 1.13 | (0.00 to 3.36) | 1– | – | 1– | – | |

| European | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4 | 1129.0 | 2.94 | (0.03 to 5.85) | 2.64 | (2.26 to 3.08) | 3.22 | (2.75 to 3.76) | |

| Asian | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Mixed race | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 526.2 | 3.78 | (0.00 to 9.08) | 3.42 | (2.89 to 4.05) | 3.47 | (2.92 to 4.11) | |

| Age group (years) | <0.0001† | <0.0001‡ | <0.0001‡ c=0.874 | <0.0001† | <0.0001‡ | |||||||||||||

| 18–25 | 2 | 310.8 | 0.94 | (0.00 to 2.28) | 3.17 | (2.46 to 4.09) | 2.50 | (2.46 to 4.09) | 10 | 1813.0 | 5.47 | (1.96 to 8.97) | 8.56 | (7.32 to 10.01) | 7.87 | (6.71 to 9.23) | ||

| 26–33 | 1 | 114.3 | 0.37 | (0.00 to 1.09) | 1.22 | (0.91 to 1.64) | 1.19 | (0.91 to 1.64) | 8 | 1562.0 | 5.01 | (1.32 to 8.69) | 7.80 | (6.66 to 9.13) | 8.49 | (7.23 to 9.98) | ||

| 34–41 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 623.4 | 2.19 | (0.00 to 5.18) | 3.31 | (2.80 to 3.92) | 3.59 | (3.03 to 4.25) | ||

| 42–49 | 1 | 73.3 | 0.28 | (0.0 to 0.84) | 1– | – | 1– | – | 1 | 174.5 | 0.67 | (0.00 to 1.99) | 1– | – | 1– | – | ||

| Province | <0.0001† | <0.0001‡ | <0.0001† | <0.0001‡ | ||||||||||||||

| Loyalty Islands | 1 | 73.3 | 1.01 | (0.00 to 2.99) | 4.99 | (3.81 to 6.54) | 6.95 | (3.81 to 6.54) | 1 | 144.6 | 1.99 | (0.00 to 5.86) | 1– | – | 1– | – | ||

| North | 2 | 230.4 | 1.04 | (0.0 to 2.49) | 4.99 | (4.12 to 6.05) | 4.11 | (4.12 to 6.05) | 8 | 1074.0 | 4.87 | (1.46 to 8.28) | 2.52 | (2.11 to 3.00) | 2.11 | (1.76 to 2.53) | ||

| South | 1 | 194.7 | 0.22 | (0.00 to 0.64) | 1– | – | 1– | – | 12 | 2954.0 | 3.3 | (1.40 to 5.20) | 1.68 | (1.42 to 1.98) | 2.37 | (1.99 to 2.82) | ||

| Marital status | <0.0001† | <0.0001‡ | <0.0001† | <0.0001‡ | ||||||||||||||

| Single | 3 | 425.1 | 0.88 | (0.00 to 1.91) | 8.42 | (6.57 to 10.80) | 6.28 | (6.57 to 10.80) | 12 | 2482.0 | 5.13 | (2.06 to 8.20) | 2.2 | (2.07 to 2.34) | 2.16 | (2.02 to 2.31) | ||

| In couples | 1 | 73.3 | 0.1 | (0.00 to 0.31) | 1– | – | 1– | – | 9 | 1691.0 | 2.4 | (0.78 to 4.02) | 1– | – | 1– | – | ||

| Study level | <0.0001† | <0.0001‡ | <0.0001† | <0.0001‡ | ||||||||||||||

| Without a diploma | 1 | 73.3 | 1.08 | (0.00 to 3.22) | 1.73 | (1.32 to 2.27) | 2.02 | (1.32 to 2.27) | 4 | 898.2 | 5.91 | (0.16 to 11.67) | 2.16 | (1.99 to 2.35) | 4.25 | (3.88 to 4.65) | ||

| Intermediate | 2 | 230.4 | 0.61 | (0.00 to 1.47) | 2.2 | (1.82 to 2.67) | 1.99 | (1.82 to 2.67) | 9 | 1406.0 | 3.74 | (1.13 to 6.35) | 1.34 | (1.25 to 1.44) | 1.81 | (1.67 to 1.96) | ||

| Bachelor and higher study | 1 | 194.7 | 0.29 | (0.00 to 0.87) | 1– | – | 1– | – | 8 | 1868.0 | 2.82 | (0.79 to 4.86) | 1– | – | 1– | – | ||

*1 missing value for ethnicity among a participant with gonorrhoea.

†RV test p<0.20.

‡RV test p<0.05.

Those aged 18–33 years were more likely to have NG and CT infections, which was most pronounced for 18–25-year-olds for all three STIs, but especially for CT infection, OR 52.1 (95% CI 42.9 to 63.4). Increasing age was clearly associated with decreasing prevalence of NG and CT. The youngest age group was also the most likely to have active syphilis, OR 2.5 (95% CI 2.5 to 4.1).

Melanesian, European and mixed race people had a higher prevalence of NG infection than Polynesians, OR Melanesians 4.1 (95% CI 3.6 to 4.8), OR Europeans 3.2 (95% CI 2.8 to 3.8), and Mixed Race OR 3.5 (95% CI 2.9 to 4.1) compared to Polynesians. No interaction was found between ethnicity and province of residence in the NG model. No Asian case of NG infection was detected (table 2). Regrouping into binary variables demonstrated that Melanesians had a higher prevalence of NG infection than all other ethnic groups, OR 1.6 (95% CI 1.5 to 1.7), regardless of province of residence. Melanesians had a higher prevalence of CT infection than all other ethnic groups. A significant interaction was found between ethnicity and province of residence in the CT model (table 3). In a model of CT infection where ethnicity was divided into five categories, odd ratio (OR) of Polynesians was 1.15 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.28) compared with Europeans (reference). All cases of active syphilis were detected only in Melanesian women, giving an adjusted prevalence of 1.1% (95% CI 0.0% to 2.2%) for active syphilis among Melanesian women.

Inhabitants of Southern and Northern Provinces had higher prevalence of NG infection than the Loyalty Islands inhabitants, OR northern inhabitants 2.1 (95% CI 1.8 to 2.5), OR southern inhabitants 2.4 (95% CI 2.0 to 2.8), with Loyalty Islands inhabitants as reference. In contrast, the Loyalty Islands and Northern inhabitants had a higher prevalence of active syphilis than Southern inhabitants, OR Loyalty Islands inhabitants 7.0 (95% CI 3.8 to 6.5), and OR Northern Province inhabitants 4.1 (95% CI 4.1 to 6.1), with inhabitants of Southern province as reference.

Single people had a higher prevalence of NG and CT infections than people in couples, OR single(NG) 2.2 (95% CI 2.0 to 2.3), OR single(CT)=1.8 (95% CI 1.7 to 1.9), with people in couples as reference. The probability of having the three STIs increased significantly with lower level of education (tables 2 and 3).

Discussion

This first cross-sectional STI survey, based on random sampling of GP surgeries and public dispensaries, established a high prevalence of CT, NG and TP infections among adults in 2012. CT infection was the most common STI, with prevalence estimated at 9% (95% CI 6.6% to 11.4%), followed by NG 3.5% (95% CI 1.9% to 5.1%), previous or latent syphilis 3% (95% CI 1.7% to 4.3%), NG and CT co-infection 2.1% (95% CI 0.8% to 3.3%), and active syphilis infection 0.4% (95% CI 0.0% to 0.9%). This study was the first to establish sociodemographic risk factors for STI in New Caledonia, showing that being from a younger age group (18–33 years, but especially 18–25 years), being single and having a low level of education were associated with higher prevalence of all three STIs. The prevalence of active syphilis and NG infections also depended on province of residence. Being of Melanesian origin was associated with a higher prevalence of CT and NG, and there was a significant interaction between ethnic group and province of residence for the prevalence of CT. For the first time in New Caledonia, men were included in an STI survey, showing that women were more likely than men to have CT infections. The study method, using family physicians to include participants, was feasible, despite existing sexual health stigma.5 20 32 33

This study was conducted in healthcare settings due to test acceptability being high among patients.5 16 17 Prevalence estimates in healthcare settings are in general higher than in population-based studies.5 16 17 Participants who refused to participate were not recorded, which meant that there could be no comparison between study participants and non-assenting patients. Participation bias may be lower in estimates from GP surgeries or public dispensaries than in general population surveys.5 The selection biases potentially introduced by physicians were addressed using a systematic step procedure that allowed random inclusion of all visitors (patients or their relatives) attending healthcare settings and corresponding to the inclusion criteria of the participants. Owing to the inclusion of relatives of patients, the population may differ from healthcare-based surveys from other countries and settings.5 16 17The study did not specifically target populations, such as pregnant women or patients having STI symptoms. In surveys conducted in healthcare settings but exclusively in pregnancy clinics17 19 20 24 26 (family planning or termination of pregnancy clinics), STI clinics (genitourinary medicine)5 17 26 or voluntary laboratories,1 13 14 the number of positive individuals is higher5 26 and participants may not have the same risks as the general adult population. Furthermore, through the implemented complex sampling design and weighting procedure, this study was related to the same age group of the general New Caledonian population and had a better geographical representation than previous studies.

This study used urine collections as specimens and not cervical swabs. Urine screening, by lower sensitivity (for instance, SE 94% vs 55.6% for NG), might result in substantial underestimation of CT and NG prevalence.34–37 Furthermore, molecular detection of NG using genital swabs and urine samples may result in false-positive results due to cross-reaction with commensal Neisseria spp or Neisseria meningitides.34–37 This could have been avoided through a confirmation test of positive samples in The COBAS AMPLICOR CT/NG tests, but was not done in this study for feasibility reasons, and also other Neisseria spp are more common in the upper respiratory tract.34–37

In previous STI surveys, conducted in 2006 in New Caledonia19 and six other Pacific Island Countries and Territories,20 pregnant women aged 15–44 years were recruited from antenatal clinics located in major urban hospitals using sampling by quota methodology. The overall study sampling size was in total 1618 pregnant women, with between 200 and 350 participants per country (152 for New Caledonia, without participants aged 40–44 years).19 20 The overall prevalence of gonorrhoea and syphilis was 1.7% and 3.4%, respectively, and the most common STI was chlamydia, with prevalence among pregnant women aged 15–25 years of 26.1%.20 The two surveys are not directly comparable, due to differences in the target population, sampling, size of sample and age group. Age group adjustments showed slightly lower prevalence of STIs in the present survey. Among women from 18 (15, in the previous study) to 25 years, the prevalence of CT in this study was 23.6% (95% CI 14.7% to 32.5%) versus 33.7%, and 8.8% (95% CI 2.8% to 14.9%) versus 10.8% for NG. From 25 to 39 years, the prevalence of CT in this study was 8.0% (95% CI 3.8% to 12.1%) versus 11.6%, and 1.9% (95% CI 0.0% to 3.7%) versus 4.3% for NG. This difference in prevalence may be explained by the difference in study population, since this study included all women (including pregnant women) while the previous New Caledonian study only included pregnant women. In this study, pregnant women had a higher prevalence of CT and NG infections than non-pregnant women, OR 1.2 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.4) and OR 1.7 (95% CI 1.5 to 2.0), respectively. However, this should be interpreted with caution, considering that there were only four pregnant women in the study population.

The prevalence of previous and latent syphilis was high (3.0% 95% CI 1.7% to 4.3%) and increased with age, and there was a difference in prevalence of active syphilis between this study (0.4% 95% CI 0.0% to 0.9%) and the previous estimate (3.3% 95% CI 1.1% to 7.5%).19 This should, however, be interpreted with caution considering that there were only four cases of active syphilis in this study. More statistical power is needed to evaluate changes in STI trends and for the calculation of some risk factors.

In France, CT and NG infection surveillance is organised in the networks Renachla (CT) and Renago (NG), through voluntary French laboratories.1 13 14 In the period 2008–2009, they demonstrated higher CT prevalence in samples collected in STI/HIV clinics (CT: 9.4%) from symptomatic individuals than in samples from GP surgeries (CT: 3.8%). The only random French population-based STI survey (Natchla)15 for 18–44 years-olds found a CT prevalence of 1.4% for men and 1.6% for women, compared to the corresponding overall prevalence in the French general population from the Renachla network of 5.3% and 5.5%, respectively.13 Comparing New Caledonia with other Pacific Island countries and territories, STI prevalence appears to be similar for CT infection, higher for NG infection and lower for active syphilis infection.20 Compared to Australia and New Zealand, prevalence for CT and for active syphilis also seem similar. The New Caledonian prevalence for NG (3.5%) in this study was one of the highest in the Pacific, if not considering a study from Papua New Guinea conducted on sex workers.26 In the USA, the most recent STI prevalence estimates, as assessed by a population-based survey, were much lower for CT and NG: 1.6% (95% CI 1.1% to 2.4%) and 0.27% (95% CI 0.13% to 0.47%), respectively.7 8 In European countries such as the UK, Slovenia and the Netherlands, prevalence estimates for CT were also lower around 3–4%.3–5 Most country estimates are, however, not derived from studies designed as this study (a healthcare-based survey of all visitors of the healthcare facility), but are either population-based, or based on specifically targeted populations, systematic STI notifications or laboratory networks.7 8 20–27 Owing to the heterogeneity in study designs, recruitment and age ranges, prevalence studies are difficult to compare between countries.7 8 13 15 20 23 25 27 Also, within New Caledonia, comparison is complicated, since the previous study targeted only pregnant women in antenatal clinics.

A limitation of this study was that there were no data on whether study participants belonged to specific risk groups. The sociodemographic risk factors for the three STIs established in this study were, however, similar to findings in the past decade from other countries.3–5 7 8 23 25 27 38

The findings of this study contribute to the regional evidence base, and also for New Caledonia. The findings will guide the development and monitoring of policy, control strategies and interventions for promoting sexual health. Further work is needed to estimate the burden of disease from STIs in New Caledonia and the Pacific, and to compare this burden with other communicable and non-communicable conditions.

Footnotes

Contributors: PC conceived and finalised the methodology design with agrement of the STI national committee (with MN, DH and BR). PC performed analyses. PC and AR performed the literature search and drafted the manuscript. BR, director of Agence sanitaire et sociale de la Nouvelle-Calédonie (ASSNC), supported the necessary infrastructure to conduct the study. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was financially supported by Agence Sanitaire et Sociale de la Nouvelle-Calédonie (ASSNC). The Territorial committee of study approved in its design

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Protocol, procedures and statistical analysis of this study were approved by the ethics committee of New Caledonia, the Advisory Committee on Information Processing in Research of the French health ministry and the National Commission for Computing and Liberties, France.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.La Ruche G, Goulet V, Bouyssou A et al. . [Current epidemiology of bacterial STIs in France]. Presse Med 2013;42(4 Pt 1):432–9. 10.1016/j.lpm.2012.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herida M, Michel A, Goulet V et al. . [Epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in France]. Med Mal Infect 2005;35:281–9. 10.1016/j.medmal.2005.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klavs I, Rodrigues LC, Wellings K et al. . Prevalence of genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in the general population of Slovenia: serious gaps in control. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:121–3. 10.1136/sti.2003.005900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Bergen J, Gotz HM, Richardus JH et al. . Prevalence of urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis increases significantly with level of urbanisation and suggests targeted screening approaches: results from the first national population based study in the Netherlands. Sex Transm Infect 2005;81:17–23. 10.1136/sti.2004.010173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams EJ, Charlett A, Edmunds WJ et al. . Chlamydia trachomatis in the United Kingdom: a systematic review and analysis of prevalence studies. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:354–62. 10.1136/sti.2003.005454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenton KA, Korovessis C, Johnson AM et al. . Sexual behaviour in Britain: reported sexually transmitted infections and prevalent genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Lancet 2001;358:1851–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06886-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datta SD, Torrone E, Kruszon-Moran D et al. . Chlamydia trachomatis trends in the United States among persons 14 to 39 years of age, 1999–2008. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:92–6. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31823e2ff7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torrone EA, Johnson RE, Tian LH et al. . Prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae among persons 14 to 39 years of age, United States, 1999 to 2008. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:202–5. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31827c5a71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Da Ros CT, Schmitt Cda S. Global epidemiology of sexually transmitted diseases. Asian J Androl 2008;10:110–14. 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00367.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dupin N. [Sexually transmitted infections in France in 2009]. Rev Prat 2010;60:520–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Schryver A, Meheus A. Epidemiology of sexually transmitted diseases: the global picture. Bull World Health Organ 1990;68:639–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wozniak TM, Moore HA, MacIntyre CR. Epidemiology of sexually transmissible infections in New South Wales: are case notifications enough? Commun Dis Intell 2013;37:e407–e414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goulet V, Laurent E, Semaille C. [Augmentation du dépistage et des diagnostics d'infections à Chlamydia trachomatis en France : analyse des données Rénachla (2007–2009)]. Bull Epidemiol Hebd 2011(26–27–28):316–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen E, Bouyssou A, Lassau F et al. . [Progression importante des infections à gonocoques en France : données des réseaux Rénago et RésIST au 31 décembre 2009]. Bull Epidemiol Hebd 2011(26–27–28):301–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goulet V, de Barbeyrac B, Raherison S et al. . Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis: results from the first national population-based survey in France. Sex Transm Infect 2010;86:263–70. 10.1136/sti.2009.038752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santer M, Warner P, Wyke S et al. . Opportunistic screening for chlamydia infection in general practice: can we reach young women? J Med Screen 2000;7:175–6. 10.1136/jms.7.4.175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pimenta JM, Catchpole M, Rogers PA et al. . Opportunistic screening for genital chlamydial infection. II: prevalence among healthcare attenders, outcome, and evaluation of positive cases. Sex Transm Infect 2003;79:22–7. 10.1136/sti.79.1.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DASSNC. Situation sanitaire en Nouvelle—Calédonie : Les infections sexuellement transmissibles I.2.2 Secondary Situation sanitaire en Nouvelle—Calédonie : Les infections sexuellement transmissibles I.2.2 2012 2011. http://www.gouv.nc/portal/page/portal/dass/librairie/fichiers/21548006.PDF.

- 19.SPC. Enquêtes de Surveillance de Deuxième Génération du VIH et autres IST et Comportements à risque en Nouvelle-Calédonie. Partie 2: Etude de la prévalence clinique des IST lors de la première consultation prénatale 2005–2006. Secondary Enquêtes de Surveillance de Deuxième Génération du VIH et autres IST et Comportements à risque en Nouvelle-Calédonie. Partie 2 : Etude de la prévalence clinique des IST lors de la première consultation prénatale 2005–2006 2007. http://www.spc.int/hiv/index2.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=207&Itemid=148

- 20.Cliffe SJ, Tabrizi S, Sullivan EA et al. . Chlamydia in the Pacific region, the silent epidemic. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:801–6. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318175d885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grulich AE, de Visser RO, Smith AM et al. . Sex in Australia: sexually transmissible infection and blood-borne virus history in a representative sample of adults. Aust N Z J Public Health 2003;27:234–41. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2003.tb00814.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston A, Fernando D, MacBride-Stewart G. Sexually transmitted infections in New Zealand in 2003. N Z Med J 2005;118:U1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis D, Newton DC, Guy RJ et al. . The prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in Australia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:113 10.1186/1471-2334-12-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panaretto KS, Lee HM, Mitchell MR et al. . Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections in pregnant urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in northern Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2006;46:217–24. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00577.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherwood J, Coughlan E. Prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections in New Zealand. N Z Med J 2007;120:U2487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vallely A, Page A, Dias S et al. . The prevalence of sexually transmitted infections in Papua New Guinea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e15586 10.1371/journal.pone.0015586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watkins RE, Mak DB, Giele CM et al. . Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal sexually transmitted infections and blood borne virus notification rates in Western Australia: using linked data to improve estimates. BMC Public Health 2013;13:404 10.1186/1471-2458-13-404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Binnicker MJ. Which algorithm should be used to screen for syphilis? Curr Opin Infect Dis 2012;25:79–85. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834e9a3c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamangar F, Islami F. Sample size calculation for epidemiologic studies: principles and methods. Arch Iran Med 2013;16:295–300. doi:013165/AIM.0010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlin JB, Hocking J. Design of cross-sectional surveys using cluster sampling: an overview with Australian case studies. Aust N Z J Public Health 1999;23:546–51. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1999.tb01317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.CALMAR 2. A new version of the CALMAR calibration adjustment program. Proceedings of the Statistics Canada Symposium; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balfe M, Brugha R, O'Connell E et al. . Men's attitudes towards chlamydia screening: a narrative review. Sex Health 2012;9: 120–30. 10.1071/SH10094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balfe M, Brugha R, O'Donovan D et al. . Young women's decisions to accept chlamydia screening: influences of stigma and doctor-patient interactions. BMC Public Health 2010; 10:425 10.1186/1471-2458-10-425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corbeto EL, Gonzalez V, Lugo R et al. . Discordant prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis in asymptomatic couples screened by two screening approaches. Int J STD AIDS 2015;26:27–32. 10.1177/0956462414528686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diemert DJ, Libman MD, Lebel P. Confirmation by 16S rRNA PCR of the COBAS AMPLICOR CT/NG test for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in a low-prevalence population. J Clin Microbiol 2002;40:4056–9. 10.1128/JCM.40.11.4056-4059.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Low N, McCarthy A, Macleod J et al. . Epidemiological, social, diagnostic and economic evaluation of population screening for genital chlamydial infection. Health Technol Assess 2007;11:iii–iv, ix-xii, 1–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tabrizi SN, Unemo M, Limnios AE et al. . Evaluation of six commercial nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and other Neisseria species. J Clin Microbiol 2011;49:3610–15. 10.1128/JCM.01217-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Datta SD, Sternberg M, Johnson RE et al. . Gonorrhea and chlamydia in the United States among persons 14 to 39 years of age, 1999 to 2002. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:89–96. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]