Abstract

The present study assessed a developmental task theory of romantic relationships by examining associations between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment across 9 years using a community based sample of 100 male and 100 female participants (M age Wave 1 = 15.83) in a Western U.S. city. Using multilevel modeling, the study examined the moderating effect of age on links between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment. Consistent with developmental task theory, high romantic quality was more associated with internalizing symptoms and dating satisfaction during young adulthood than adolescence. Romantic relationship qualities were also associated with externalizing symptoms and substance use, but the degree of association was consistent across ages. The findings underscore the significance of romantic relationship qualities across development.

Keywords: Romantic Relationships, Conflict, Support, Dating, Internalizing Symptoms, Externalizing Symptoms, Substance Use, Satisfaction

Throughout the lifespan, individuals encounter a series of developmental tasks, which reflect widely held expectations regarding age appropriate behavior (McCormack, Kuo, & Masten, 2011). One such developmental task is the emergence and maintenance of romantic relationships (Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004). Developmental task theory proposes that romantic relationships are an emerging developmental task in adolescence and become a salient development task in adulthood (Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Cauffman, Spieker & The NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2009; Roisman et al., 2004). When it is an emerging developmental task, the quality of such romantic relationships is not expected to be especially related to future adaptation, because of the variability and instability of the transitional period. As an emerging task, adolescents may be less likely to benefit from higher quality relationships as they navigate new experiences and learn to manage new stressors associated with romantic relationships. However, the quality of romantic relationships once they are a salient developmental task is expected to be associated with future adaptation (Ford & Lerner, 1992; Roisman, et al., 2004; Thelen & Smith, 1998). By the same reasoning, the quality of functioning within romantic relationships may be related to concurrent adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood, but such associations should be stronger in young adulthood. The present study tested this aspect of developmental task theory by examining developmental shifts in associations between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment from adolescence into young adulthood.

One tenant of developmental task theory is that romantic relationships change as a function of development (McCormick et al., 2011). Shifts in the nature of romantic relationships reflect the progression of romantic relationships from an emerging to a salient task. Indeed, such shifts also reflect the growing significance of these relationships for youth, such that as these experiences become more developed and salient, they should also become increasingly tied to adjustment. Consistent with this theory, as adolescents become older and transition into young adulthood, romantic partners increase in their importance and are more likely to serve as safe havens or secure bases (Hazan & Zeifman, 1994). Romantic relationships also become increasingly supportive, more intimate, and more interdependent as adolescents get older and move into young adulthood (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992; Giordano, Manning, Longmore, & Flanigan, 2012; Seiffge-Krenke 2003). Furthermore, as adolescents get older, they begin to rank their romantic partners as higher on a hierarchy of support figures (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). Romantic relationships also become more serious and committed; as adolescents move into young adulthood, they become increasingly likely to have relationships of longer duration, and to report being in love (Furman & Winkles, 2011). Overall, the pattern suggests that adolescent romantic relationships may initially center around affiliation and sexual activity when they are first emerging, but they become increasingly significant and valued as adolescents transition to young adulthood and these experiences become a salient developmental task (Furman & Wehner, 1997).

The idea that romantic relationships not only become more common, but also shift in their nature, is a core tenant of developmental task theory. In addition to these developmental shifts, preliminary evidence suggests associations between quality of functioning within romantic relationships and adjustment exist. Indeed, a developmental task theory would suggest that the quality of functioning within salient developmental tasks may be most predictive of adaptation (Roisman et al., 2004). Among young adults, higher relationship quality is associated with more positive adjustment (Kamp Dush & Amato, 2005; Segrin, Powell, Givertz, & Brackin, 2003; Simon & Barrett, 2010). Yet, among adolescents, these associations are less consistent and not as well-understood (c.f. La Greca & Harrison, 2005; Zimmer-Gembeck, Siebenbruner, & Collins, 2001). Our limited understanding of these associations in adolescence reflects the fact that most studies of adolescents have examined whether one has a relationship or the degree of romantic involvement, rather than the quality of that involvement (Davila, 2008).

The associations between romantic involvement and adjustment have received significant attention, and the literature has consistently demonstrated links between romantic involvement and internalizing problems in adolescence, particularly among girls (Connolly & McIsaac, 2009; Davila 2011; Joyner & Udry, 2000; Starr et al., 2012). However, the extant literature has not yet examined if and when the quality of romantic relationships emerge to serve protective functions for adjustment. More recently, prior work using the same dataset as this study examined how associations between romantic involvement and adjustment change developmentally (Furman & Collibee, 2014). Specifically, having a romantic partner was associated with greater levels of substance use, externalizing symptoms, and internalizing symptoms in adolescence, but was associated with lower levels in young adulthood. However, this work did not examine the nature of that romantic involvement. An examination of the associations between romantic qualities and adjustment not only addresses a separate and significant gap in the literature, but also allows us to test a distinct and important aspect of a developmental task theory--that the quality of functioning within the task (i.e. romantic relationships) should become increasingly related to adjustment as the task becomes salient.

Additionally, most studies which consider the quality of the romantic experiences have only examined one age group. Studying the associations between the quality of romantic relationships and adjustment from adolescence to young adulthood longitudinally may be particularly illuminating in understanding the developmental course of romantic relationships as a developmental task. Specifically, we would anticipate that the quality of romantic relationships would become increasingly associated with adjustment as it becomes a salient developmental task. The few studies which have compared these links in adolescence and young adulthood offer evidence consistent with a developmental task theory. Specifically, romantic relationship security is more strongly associated with fewer externalizing symptoms in young adulthood than in adolescence (Van Dulmen, Goncy, Haydon, & Collins, 2008). For individuals whose most significant peer is a romantic partner, greater commitment is associated with fewer emotional problems in early adulthood, but not in adolescence (Meeus, Branje, van der Valk, & de Wied, 2007). As such, this preliminary work indeed suggests that differential associations may exist between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment developmentally. However, these works each examine only two time points, limiting our understanding of the developmental course of these links, an important aspect of testing a developmental task theory. Additionally, only a few relationship qualities and indices of adjustment have been examined to date.

The current study assessed the associations between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment over a nine year period from middle adolescence to young adulthood (15-24 years of age) as a test of developmental task theory. Specifically, we examined the links between romantic relationship quality (support, negative interactions, and romantic relationship satisfaction) and adjustment (internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, substance use, and overall dating satisfaction), across time. We selected internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and substance use because they are broad and important aspects of adjustment and romantic relationships. We included relationship satisfaction as one of our indices of relationship quality, but we also included overall dating satisfaction as an index of adjustment because romantic relationship qualities likely influence feelings of dating satisfaction over time as well. Past research has examined satisfaction with a particular romantic relationship in adolescence (e.g., Levesque, 1993; Overbeek, Ha, Scholte, de Kemp & Engels, 2007; Welsh, Haugen, Widman, Darling & Grello, 2005), but we believe this is one of the first studies to examine overall satisfaction with dating life during adolescence. Overall dating satisfaction is an important construct that is somewhat distinct from satisfaction with a particular relationship, as it may not only be influenced by feelings toward a current partner, but also by the qualities of past relationships, the number of individuals they have seen romantically, and whether they have a current relationship or not.

We expected that the associations between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment would reflect that romantic relationships are an emerging developmental task in adolescence, yet become a salient developmental task in young adulthood. Thus, we hypothesized that the associations between romantic quality and adjustment would vary as a function of age, such that we would see links between greater relationship quality and fewer adjustment problems across development, but that these links would get stronger as youth grow older and became young adults.

Method

Participants

The participants were part of a longitudinal study investigating the role of relationships with parents, peers, and romantic partners on psychosocial adjustment. Two hundred 10th grade high school students (100 boys, 100 girls; M age = 15 years 10.44 months old, SD = .49 years) were recruited. The participants came from 37 zip codes of working class to upper middle class neighborhoods in a large Colorado metropolitan area. We sought to obtain a diverse sample by distributing brochures and sending letters to families residing in a number of different zip codes and to students enrolled in various schools in ethnically diverse neighborhoods. We were unable to determine the ascertainment rate because we used brochures and because the letters were sent to many families who did not have a 10th grader. We contacted interested families with the goal of selecting a sample that had an equal number of males and females, and had a distribution of racial/ethnic groups that approximated that of the United States. To ensure maximal response, we paid families $25 to hear a description of the project in their homes. Of the families that heard the description, 85.5% expressed interest and carried through with the Wave 1 assessment.

The sample consisted of 11.5% African Americans, 12.5% Hispanics, 1.5% Native Americans, 1% Asian American, 4% biracial, and 69.5% White, non-Hispanics. With regard to family structure, 57.5% were residing with 2 biological or adoptive parents, 11.5% were residing with a biological or adoptive parent and a step parent or partner, and the remaining 31% were residing with a single parent or relative. The sample was of average intelligence (WISC-III vocabulary score M = 9.8, SD = 2.44); 55.4% of their mothers had a college degree, indicating that the sample was predominately middle or upper middle class.

As part of the larger project, the participants and their mothers completed a number of other measures in Wave 1. Although these measures are not directly relevant to this particular study, we compared our sample’s scores to comparable national norms of representative samples for trait anxiety scores on the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, 1983), maternal report of externalizing symptoms on the Child Behavior Child Checklist (Achenbach, 1991), participants’ reports of internalizing and externalizing symptoms on the Youth Self Report, and 8 indices of substance use from the Monitoring the Future survey (Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 2002). The present sample was more likely to have tried marijuana (54% vs. 40%, z = 2.23, p < .05); otherwise the sample scores did not differ significantly from the national scores on the other 11 measures, including frequency of marijuana usage

Procedure

Adolescents participated in a series of laboratory sessions in which they were interviewed about romantic relationships and completed questionnaires. The mother (N = 169) and a close friend (N = 145) nominated by the participant also completed questionnaires about the participant’s psychosocial competence and risky/problem behaviors.

For the purposes of the current study, we used the first through seventh waves of data collection, beginning when the participants were in the 10th grade and ending approximately 5.5 years after graduation from high school. Data were collected on a yearly basis in Waves 1 through 4, and then one and a half years later for Waves 5-7. The seven waves of data were collected between 2000 and 2010. Participant retention was excellent (Wave 1 & 2: N = 200; Wave 3: N = 199, Wave 4: N = 195, Wave 5: N = 186, Wave 6: N = 185, Wave 7: N = 179). There were no differences on the variables of interest between those who did and did not remain in the study.

The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Network of Relationships Inventory: Behavioral Systems Version (NRI)

(Furman & Buhrmester, 2009). Participants completed the NRI to assess their perceptions of their most important romantic relationship in the last year. The short version of the NRI includes five items regarding social support and six items regarding negative interactions. Participants used a 5 point scale to rate how much each description was characteristic of their romantic relationship, and support and negative interaction scores were derived by averaging the relevant items (M α = .89 & M α = .92, respectively).

Romantic Relationship Satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction was assessed through an adapted version of the Quality of Marriage Inventory (QMI; Norton, 1983). The QMI is a 6-item self-report measure that assesses an individual’s global perception of his or her relationship quality (Baxter & Bullis, 1986) and was adapted to assess relationship satisfaction among adolescents and young adults. An example of a question is “My relationship with my boy/girlfriend makes me happy” which the participant then responds to on a 7 point Likert scale (1= strongly disagree/not at all true to 7 = strongly agree/very true; M alpha = .97).

Dating Satisfaction

On the Dating History Questionnaire (Furman & Wehner, 1992) participants were asked, “How satisfied have you been with your romantic or dating life (or not dating, if you don’t date)?” Satisfaction was rated on a five-point scale. Convergent validity correlations can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patterns of Correlations between Romantic Qualities and Adjustment Outcomes at Wave 1

| Support | Negative Interactions |

Relationship Satisfaction |

Internalizing Symptoms |

Externalizing Symptoms |

Substance Use |

Dating Satisfaction |

Age | |

|

| ||||||||

| Support | ||||||||

| Negative Interactions |

−.07 | |||||||

| Relationship Satisfaction |

.64* | −.33* | ||||||

| Internalizing Symptoms |

−.09 | .08 | −.04 | |||||

| Externalizing Symptoms |

−.14 | .21* | −.17 | .40* | ||||

| Substance Use | −.06 | .06 | −.20* | .04 | .17* | |||

| Dating Satisfaction |

.14 | .06 | .31* | −.14* | −.02 | −.01 | ||

| Age | .07 | .05 | .02 | .10 | .03 | −.01 | .06 | |

|

Patterns of Correlations between Romantic Qualities and Adjustment Outcomes at Wave 7

| ||||||||

| Support | Negative Interactions |

Relationship Satisfaction |

Internalizing Symptoms |

Externalizing Symptoms |

Substance Use |

Dating Satisfaction |

Age | |

|

| ||||||||

| Support | ||||||||

| Negative Interactions |

−.17 | |||||||

| Relationship Satisfaction |

.61* | −.36* | ||||||

| Internalizing Symptoms |

−.27* | .35* | −.39* | |||||

| Externalizing Symptoms |

−.23* | .32* | −.20* | .49* | ||||

| Substance Use | −.17 | .16 | −.23* | .15 | .23* | |||

| Dating Satisfaction |

.47* | −.21* | .50* | −.34* | −.30* | −.10 | ||

| Age | −.07 | .05 | .01 | .00 | .04 | .07 | −.04 | |

p < .05

Youth/Adult Self Report

Participants completed the Achenbach’s (1991) Youth Self-Report in Waves 1-3 and Achenbach’s (1997) Adult Self-Report in Waves 4-7. Internalizing and externalizing scores were derived from the 20 and 26 items that were comparable on the two versions (M α = .81 & .87, respectively).

Child/Adult Behavior Checklist

Friends and mothers reported on the participant’s externalizing symptoms by completing the externalizing items of the Child Behavior Checklist in Waves 1-3, and the externalizing items on (1997) Adult Behavior Checklist in Waves 4-7 (Achenbach, 1991, 1997). Friend and mother reports of externalizing scores were derived from the 19 items that were comparable on the two versions (M α = .84 & .89, respectively).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

Participants completed the BDI to assess depressive symptoms (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) (M α = .86).

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

Participants completed the trait scale of Spielberger’s (1983) STAI to assess anxious symptoms (M α = .92)

Drug Involvement Scale for Adolescence (DISA)

Participants completed the Drug Involvement Scale for Adolescence (Eggert, Herting, & Thompson, 1996). For the present purposes, we examined use of beer, wine, liquor, marijuana, and other drugs (cocaine, opiate, depressants, tranquilizers, hallucinogens, inhalants, stimulants, over-the-counter drugs, club drugs) over the last 30 days. Frequency of each substance use was scored on a 7-point scale ranging from never to every day. Additionally, they completed a 16 item measure assessing adverse consequences arising from substance use (M α =.94), and an 8 item measure assessing difficulties in controlling substance use (M α =.91). The questionnaires on sexual behavior and substance use were administered by computer assisted self-interviewing techniques to increase the candor of responses.

Friends Report of Substance Use

As part of their version of the Adolescent Self-Perception Profile (Harter, 1988), friends were asked five questions about the participant’s use of alcohol and drugs and problems related to the use of those substances. The five items were averaged to derive the friend report of the participant’s substance use and problems (M α =.82).

Derivation of composites

The participants’, friends’, and mothers’ reports of externalizing symptoms were standardized across waves and averaged to derive an index of externalizing symptoms. BDI depression scores, STAI anxiety scores, and internalizing symptom scores were each standardized across waves and averaged to derive an index of internalizing symptoms. The various measures of the internalizing composite were correlated at M r = .66 and externalizing measures were correlated at M r = .32, and were all significant correlations.

The participants’ reports of beer/wine drinking and their reports of drinking liquor were each standardized across waves and averaged to derive a measure of alcohol use. Similarly, the participants’ reports of marijuana use, and their reports of other drug use were standardized across waves and averaged to derive a measure of drug use. The participants’ reports of problems and their reports of control problems were each standardized across Waves and averaged to derive a measure of problem usage. The friends’ reports of substance use were also standardized across waves. The alcohol, drug, and problem usage, and friends’ reports of substance use were all significantly correlated, with a M r = .55, and they were averaged to derive a measure of substance use.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

All variables were examined to insure that they had acceptable levels of skew and kurtosis (Behrens, 1997). Outliers were Winsorized to fall 1.5 times the interquartile range below the 25th percentile or above the 75th percentile. Additional descriptive statistics can be found in Table 1 and correlations among the study variables at Wave 1 and Wave 7 can be found in Table 2. Support and relationship satisfaction increased over time, though negative interactions did not (see Lantagne & Furman, 2015). In Wave 1, 59.8% of participants reported having had a romantic partner in the last year; in Wave 2, 66% had a romantic partner; in Wave 3, 78.2% had a romantic partner; in Wave 4, 75.9% had a romantic partner; in Wave 5, 73.5% had a romantic partner; in Wave 6, 79.9% had a romantic partner; in Wave 7, 80.6% had a romantic partner. Participant’s reports of whether they had a romantic relationship or not was used as a measure of romantic involvement in the analyses.

Table 1.

Mean Romantic Involvement and Adjustment Outcomes (with Standard Deviations in Parentheses)

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | Wave 5 | Wave 6 | Wave 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.88 (0.47) | 16.89 (0.47) | 17.94 (0.50) | 19.03 (0.56) | 20.51 (0.56) | 22.11 (0.51) | 23.70 (0.61) |

| Support | 3.07 (1.03) | 3.52 (1.08) | 3.52 (1.05) | 3.73 (1.00) | 3.66 (1.04) | 3.84 (0.98) | 3.93 (0.96) |

| Negative Interactions |

1.82 (0.75) | 1.71 (0.76) | 1.95 (0.94) | 1.74 (0.79) | 1.88 (0.81) | 1.79 (0.75) | 1.74 (0.61) |

| Relationship Satisfaction |

11.34 (4.42) | 12.28 (4.56) | 12.03 (4.81) | 13.63 (4.13) | 12.26 (4.87) | 13.10 (4.64) | 13.18 (4.48) |

| Internalizing | 0.16 (0.91) | 0.16 (0.94) | 0.05 (0.89) | −0.04 (0.86) | −0.04 (0.85) | −0.12 (0.83) | −0.18 (0.91) |

| Externalizing | 0.27(0.87) | 0.13 (0.82) | 0.14 (0.85) | 0.04 (0.78) | −0.14 (0.66) | −0.24 (0.68) | −0.31 (0.68) |

| Substance Use | −0.26 (0.49) | −0.14 (0.59) | −0.05 (0.63) | 0.07 (0.58) | 0.18 (0.65) | 0.33 (0.61) | 0.33 (0.65) |

| Dating Satisfaction |

3.25 (0.98) | 3.38 (1.08) | 3.40 (1.07) | 3.56 (1.07) | 3.54 (1.17) | 3.61 (1.19) | 3.64 (1.15) |

Primary Analyses

We aimed to examine the pattern of associations between romantic quality and adjustment developmentally with a series of multilevel models (MLMs) using the statistical program Hierarchical Linear Modeling Version 6.0 which uses full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to estimate parameters when data are missing (HLM; Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2001). FIML provides a powerful alternative to listwise deletion and protects against bias in analyses (Graham, Olchowski, & Gilreath, 2007; Little, Jorgensen, Lang, & Moore, 2013). When participants did not have a romantic relationship at a certain wave, romantic qualities (i.e. support, negative interactions, and relationship satisfaction) were entered as missing. However, those participants who did not have a romantic relationship in a certain wave provided information on other variables of interest, including internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, substance use, and romantic life satisfaction. Thus, existing data from all waves from all participants were used. To test our hypotheses regarding the developmental task theory, we used the following model.

Level 1

Yi = β0 + β1(romantic involvement)+ β2(age) + β3(romantic quality) + β4 (age x romantic quality) + ri

Level 2

β0 = γ00 + γ01(gender) + u0

β1 = γ10

β2 = γ20

β3 = γ30

β4 = γ40

We used a two-step model to examine these associations, with both romantic qualities and age grand mean centered. First, we conducted a model with gender, romantic involvement, age, and romantic quality. We controlled for romantic involvement to assess if the quality of romantic relationships is associated with adjustment above the presence of a relationship. Next, we examined the interaction effects after the main effects to avoid concerns of conditionality (Little, 2013). We tested for significant random effects, and found significant random slopes for age when predicting internalizing or externalizing symptoms using a p < .20 cutoff (Nezlek, 2012). In those instances, the above equation included that random effect at level 2. Table 3 reports the results of these analyses. Though all the effects are presented together, the unstandardized regression coefficients and standard errors are the values at the step in which these terms were first entered in the model. We also examined 2-way and 3-way interactions with gender, and found there were none.

Table 3.

Multilevel Models Testing the Associations between Romantic Relationship Qualities and Adjustment

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support | Internalizing | Externalizing | Substance Use | Dating Satisfaction |

|

|

||||

| Intercept (β0) | 0.00 (.05) | −0.02 (.04) | 0.01 (.03) | 3.58 (.13) |

| Romantic Involvement (β1) | 0.04 (.04) | 0.04 (.04) | 0.57* (.23) | 0.33 (.48) |

| Age (β2) | −0.05** (.01) | −0.08*** (.01) | 0.03*** (.01) | 0.01 (.01) |

| Support (β3) | −0.10*** (.02) | −0.06** (.02) | −0.02 (.02) | 0.41*** (.03) |

| Support X Age (β4) | −0.02* (.01) | −0.01 (.01) | −0.01 (.01) | 0.03* (.01) |

| Gender Main Effect (γ01) | 0.23* (.10) | −0.11 (.09) | −0.06 (.06) | −0.05 (.09) |

| Negative Interactions | ||||

| Intercept (β0) | 0.06 (.09) | 0.00 (.09) | −0.09 (.07) | 3.51 (.05) |

| Romantic Involvement (β1) | −0.22 (.30) | 0.06 (.28) | 0.57* (.24) | 0.51 (.51) |

| Age (β2) | −0.05*** (.01) | −0.09*** (.01) | 0.02*** (.01) | 0.05*** (.01) |

| Negative Interactions (β3) | 0.21* (.03) | 0.13*** (.03) | 0.05* (.02) | −0.18*** (.05) |

| Negative Interactions X Age (β4) | 0.02* (.01) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.00 (.01) | −0.06** (.02) |

| Gender Main Effect (γ01) | 0.25* (.10) | −0.11 (.09) | −0.08 (.06) | 0.05 (.10) |

| Romantic Relationship Satisfaction | ||||

| Intercept (β0) | −0.00 (.06) | 0.01 (.05) | 0.02 (.04) | 3.56 (.07) |

| Romantic Involvement (β1) | 0.01 (.15) | −0.01 (.12) | 0.13 (.11) | 0.26 (.22) |

| Age (β2) | −0.05*** (.01) | −0.08*** (.01) | 0.02*** (.01) | 0.03** (.01) |

| Relationship Satisfaction (β3) | −0.03*** (.01) | −0.02** (.004) | −0.01* (.004) | 0.10*** (.01) |

| Relationship Satisfaction X Age (β4) | −0.01** (.00) | −0.01 (.01) | −0.003* (.001) | 0.01** (.003) |

| Gender Main Effect (γ01) | 0.25* (.10) | −0.13 (.09) | −0.08 (.06) | −0.01 (.08) |

Notes. The primary numbers in the table are the unstandardized coefficients for the fixed effects. Standard errors are in parentheses.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Internalizing symptoms

Romantic support

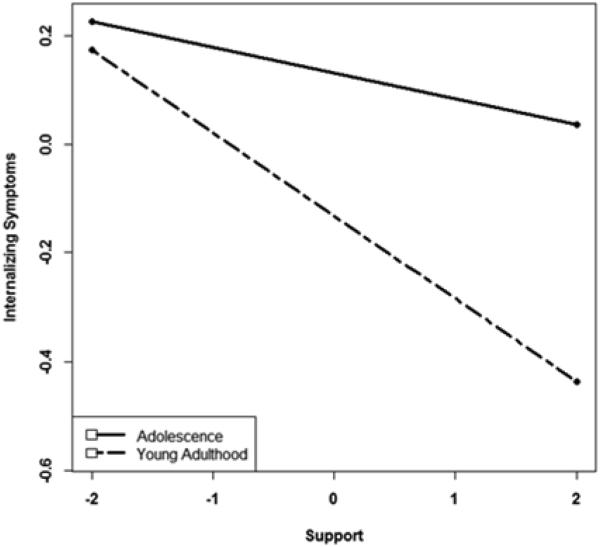

Consistent with a developmental task theory hypothesis, main effects of both age and romantic support on internalizing symptoms were found, but they were qualified by a significant interaction between age and romantic support (see Figure 1). To further interpret this and the other significant interactions, we used Preacher, Curran, & Bauer’s (2006) computational tools to plot the estimated effects of romantic qualities on change in the adjustment measure for two values of age: 1 SD below the mean age across all 7 waves (16.66 years), and 1 SD above the mean age across all 7 waves (21.92 years). In young adulthood, higher romantic support was associated with lower internalizing symptoms (β = −.15, t(897) = −4.62, p < .001). In adolescence, internalizing symptoms did not differ by degree of romantic support (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interaction between support and age on internalizing symptoms. The two lines depict the association between support and internalizing symptoms at one SD below the mean of age (16.66 years, labeled adolescence), and one SD above the mean age (21.92 years, labeled young adulthood). Internalizing symptoms scores are standardized.

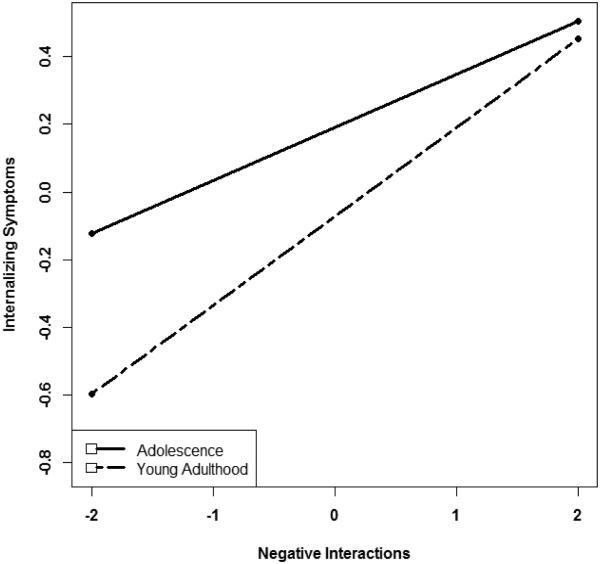

Negative interactions

Consistent with hypotheses, a main effect of both age and negative interactions were found on internalizing symptoms, but again they were qualified by a significant interaction between age and negative interactions. As seen in Figure 2, higher negative interactions were associated with higher internalizing symptoms in both adolescence and young adulthood, but the association was stronger in young adulthood (β = .16 t(902) = 3.95, p < .001 & β = .26 t(902) = 6.58, p < .001, respectively).

Figure 2.

Interaction between negative interactions and age on internalizing symptoms. The two lines depict the association between negative interactions and internalizing symptoms at one SD below the mean of age (16.66 years, labeled adolescence), and one SD above the mean age (21.92 years, labeled young adulthood). Internalizing symptoms scores are standardized.

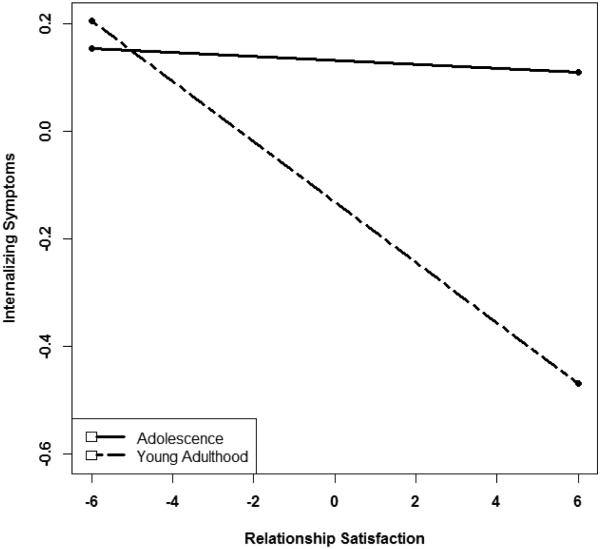

Relationship satisfaction

Consistent with hypotheses, main effects of both age and romantic relationship satisfaction were found on internalizing symptoms, but again they were qualified by a significant interaction between age and relationship satisfaction. As seen in Figure 3, romantic relationship satisfaction was associated with lower internalizing symptoms in young adulthood (β = −.06, t(898) = −5.45, p < .001). In adolescence, internalizing symptoms did not differ by degree of relationship satisfaction.

Figure 3.

Interaction between relationship satisfaction and age on internalizing symptoms. The two lines depict the association between relationship satisfaction and internalizing symptoms at one SD below the mean of age (16.66 years, labeled adolescence), and one SD above the mean age (21.92 years, labeled young adulthood). Internalizing symptoms scores are standardized.

Externalizing symptoms

Romantic support

Main effects of both age and romantic support were found. There was a negative association with age, such that as individuals get older, they had fewer externalizing symptoms. Similarly, there was a negative association with romantic support, such that individuals with higher levels of romantic support had lower levels of externalizing symptoms. Contrary to hypotheses, no interaction between romantic support and age was found.

Negative Interactions

Main effects of both age and negative interactions were found, such that as individuals got older they had fewer externalizing symptoms. Similarly, there was a positive association with negative interactions, such that individuals with higher levels of negative interactions had higher levels of externalizing symptoms. Contrary to hypotheses, no interaction between negative interactions and age was found.

Relationship Satisfaction

Main effects of both age and romantic relationship satisfaction were found. There was a negative association with age, such that as individuals got older they had fewer externalizing symptoms. Similarly, there was a negative association with romantic relationship satisfaction, such that individuals with higher levels of relationship satisfaction had lower levels of externalizing symptoms. Contrary to hypotheses, no interaction between relationship satisfaction and age was found.

Substance use

Romantic support

Regarding substance use, a main effect of age was found, such that as individuals got older they reported higher substance use. Contrary to hypotheses, neither the main effect of romantic support nor the interaction between romantic support and age was significant.

Negative interactions

Main effects of both age and negative interactions were found. There was a negative association with age, such that as individuals got older, they had fewer externalizing symptoms. Similarly, there was a positive association with negative interactions, such that individuals with higher levels of negative interactions had higher levels of substance use. Contrary to hypotheses, no interaction between negative interactions and age was found.

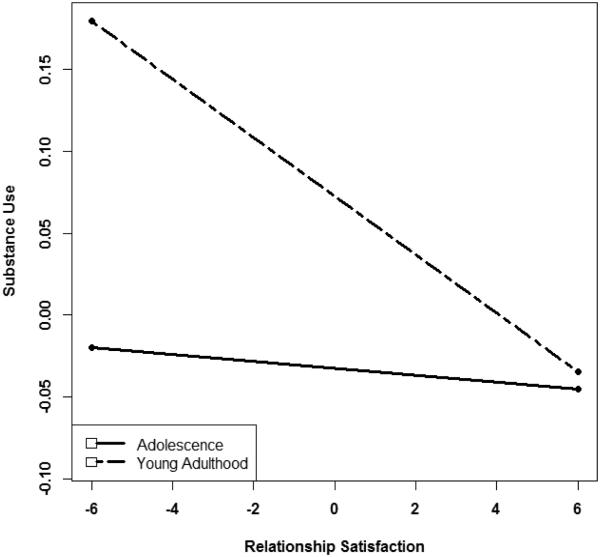

Relationship satisfaction

Regarding substance use, a main effect age was found, such that as individuals got older, they reported higher substance use. There was no main effect of relationship satisfaction on substance use. Consistent with hypotheses, there was a significant interaction between age and relationship satisfaction on substance use. As seen in Figure 4, in young adulthood, high relationship satisfaction was associated with lower substance use (β = −.02, t(905) = −3.74, p < .001). In adolescence, substance use did not differ by degree of relationship satisfaction.

Figure 4.

Interaction between relationship satisfaction and age on substance use. The two lines depict the association between relationship satisfaction and substance use at one SD below the mean of age (16.66 years, labeled adolescence), and one SD above the mean age (21.92 years, labeled young adulthood). Substance use scores are standardized.

Dating satisfaction

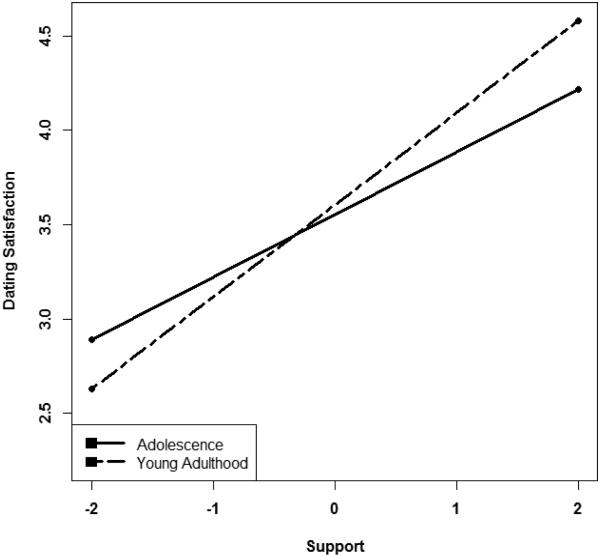

Romantic support

Consistent with hypotheses, a main effect of romantic support was found, but it was qualified by a significant interaction between age and romantic support. In both adolescence and young adulthood, high romantic support was associated with high dating satisfaction, but the association was stronger in young adulthood (β = .33, t(884) = 8.30, p < .001 & β = .49, t(884) = 12.25, p < .001, respectively; see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Interaction between support and age on dating satisfaction. The two lines depict the association between support and dating satisfaction at one SD below the mean of age (16.66 years, labeled adolescence), and one SD above the mean age (21.92 years, labeled young adulthood).

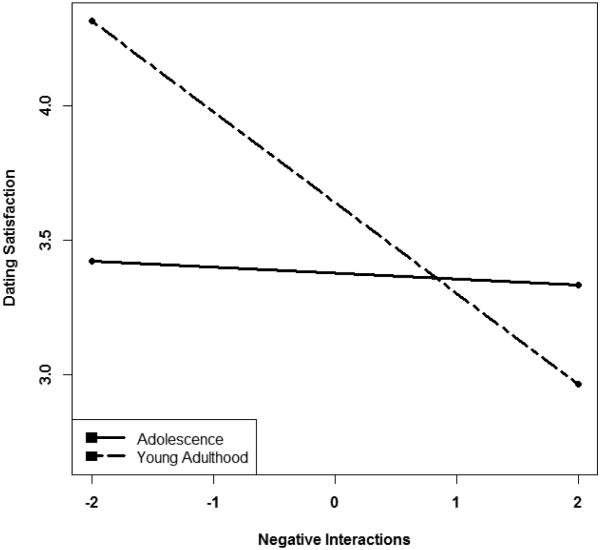

Negative interactions

Consistent with hypotheses, a main effect of negative interactions was found, but was qualified by a significant interaction between age and negative interactions on dating satisfaction. As seen in Figure 6, higher rates of negative interactions were associated with lower dating satisfaction in young adulthood (β = −.34 t(889) = −4.66, p < .001). In adolescence, dating satisfaction did not differ by degree of negative interactions.

Figure 6.

Interaction between negative interactions and age on dating satisfaction. The two lines depict the association between negative interactions and dating satisfaction at one SD below the mean of age (16.66 years, labeled adolescence), and one SD above the mean age (21.92 years, labeled young adulthood).

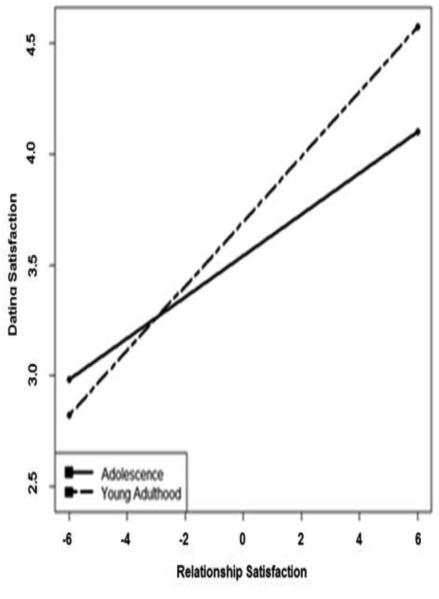

Relationship satisfaction

Consistent with hypotheses, main effects of relationship satisfaction and age were found, but were qualified by a significant interaction between age and relationship satisfaction on dating satisfaction. As seen in Figure 7, higher relationship satisfaction was associated with higher dating satisfaction in adolescence and young adulthood, though the association was greater in young adulthood (β = .07, t(897) = 5.79, p < .001 & β = .13, t(897) = 9.92, p < .001, respectively).

Figure 7.

Interaction between relationship satisfaction and age on dating satisfaction. The two lines depict the association between relationship satisfaction and dating satisfaction at one SD below the mean of age (16.66 years, labeled adolescence), and one SD above the mean age (21.92 years, labeled young adulthood).

Secondary Analyses

The preceding analyses examine the links from romantic quality to adjustment. We next conducted a series of follow-up analyses examining the links from adjustment to romantic qualities, so as to better understand the potential directionality of these associations. We found significant main effects for internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms predicting lower support and relationship satisfaction, as well as greater negative interactions. Similarly, dating satisfaction predicted higher support and relationship satisfaction as well as lower rates of negative interactions. Substance use predicted greater negative interactions, but was not associated with support or relationship satisfaction. Regarding interactions between adjustment and age, the specific interactions varied, but the pattern of effects mirrored those in the primary analyses. In other words, in instances of significant interactions, adjustment became increasingly predictive of romantic qualities developmentally, consistent with developmental task theory. Results and plots are available as supplemental materials from the corresponding author.

Discussion

Past research has documented links between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment, but virtually all the work is cross-sectional in nature, examining one or at most two time points. The present study contributes to the literature by longitudinally examining the developmental course of associations between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment over a 9 year period spanning adolescence and young adulthood. Based on developmental task theory, we hypothesized that romantic relationship qualities would be associated with adjustment throughout this age period, but the quality of functioning within romantic relationships would become increasingly tied to concurrent adjustment as romantic relationships become a salient development task in young adulthood. As predicted, we found increasing associations between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment as youth got older in 7 of 12 instances; in 4 of the 5 remaining instances, significant main effects of romantic quality on adjustment were found. Notably, these main effects of quality were found even when controlling for relationship involvement.

Consistent with a developmental task theory, the associations between romantic relationship qualities and dating satisfaction were stronger in young adulthood than in adolescence. Such a pattern was observed for all three relationship qualities (support, negative interactions, and relationship satisfaction). These changing associations are particularly notable, as one might intuitively expect that romantic relationship qualities would be strongly associated with overall satisfaction with dating life at all ages. Indeed, prior work has demonstrated that adolescents prefer higher quality romantic partnerships (Levesque, 1993). However, these shifts can be accounted for by developmental task theory. During adolescence, when romantic relationships are an emerging developmental task, simply having a romantic relationship, having a number of relationships, or having a relationship with an attractive or otherwise desirable partner may play major roles in determining one’s overall dating satisfaction, which may result in the quality of a relationship per se being less significant. In contrast, as romantic relationships become a salient developmental task, the quality of the relationship may become increasingly important to overall satisfaction. That is, the quality of a specific relationship becomes more predictive of overall dating satisfaction than other features of romantic life.

The findings regarding internalizing symptoms were also consistent with developmental task theory. As hypothesized, the associations between all three romantic relationship qualities and internalizing symptoms were stronger in young adulthood than in adolescence. When romantic relationships are a salient developmental task, poorer quality ones may lead to feelings of depression or anxiety. Alternatively, those who are depressed or anxious may have more difficulties establishing or maintaining high quality relationships (Davila, 2008). Indeed, the supplemental analyses demonstrated significant associations from internalizing symptoms to romantic qualities. Thus, regardless of the directionality, it is clear that links between adjustment and romantic qualities are present across development, and strengthen as romantic experiences become a salient task.

Finally, romantic relationship satisfaction was only associated with substance use in early adulthood. Perhaps, if substance use functions as a means of coping with dissatisfaction, then the increasing saliency of this dissatisfaction may be linked to higher levels of relying on substances to manage discontent. We did not, however, find similar interactions with age for either support or negative interactions. It is possible that support and negative interactions may not trigger such direct affective responses which then may lead to maladaptive coping. Given the differences in the findings among the different qualities it will be important to replicate them before drawing firm conclusions.

The significant interactions with age for overall dating satisfaction, internalizing symptoms, and substance use are consistent with a developmental task theory of romantic relationship development. One explanation why romantic qualities become increasingly associated with adjustment is a stress and coping model of romantic experiences. This model posits that romantic experiences in adolescence may be stressful and overwhelming, thereby placing youth at risk for adjustment problems (Davila, 2008). In other words, adolescents may lack the necessary emotion regulation or coping skills to manage the stressors associated with romantic relationships. Though one might expect that romantic stressors and the quality of romantic relationships would be somewhat related, the challenges adolescents face in coping with most romantic relationships may be more related to simply initiating and maintaining the relationships, and thus the quality of a relationship may play a less significant role in affecting adjustment. Further, the stressors associated with romantic involvement may be unrelated to the quality of the specific relationship. For example, adolescents may need to learn how to balance desires to spend time with a romantic partner and other academic or familial obligations. As adolescents transition into young adulthood, this model posits that they develop more coping skills and experience to better manage romantic stressors, and therefore may be able to benefit more from the social and emotional resources high quality romantic relationships offer.

Contrary to our hypotheses, age did not moderate the associations between romantic relationship qualities and externalizing symptoms as well as most substance use variables. Substance use in particular has the greatest variability in patterns of findings. This variability may stem from the fact that the associations between romantic relationship quality and substance use depend on the patterns of partner substance use in young adulthood (Fleming, White, & Catalano, 2010). Further research examining these developmental changes should therefore incorporate assessments of partner substance use to better understand these associations.

Main effects of romantic quality were also found for externalizing symptoms such that greater support, greater relationship satisfaction, and fewer negative interactions were associated with fewer externalizing symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood. Indeed, other empirical evidence is consistent with these results. Specifically, romantic partner support is associated with less criminality in both adolescence and young adulthood (Meeus, Branje, & Overbeek, 2004).

What might account for the difference between the pattern of associations with externalizing and those with internalizing symptoms or dating satisfaction? One possibility is that externalizing symptoms are more stable than internalizing symptoms or dating satisfaction and as a consequence, the externalizing symptoms’ associations with other variables may be less likely to increase with age. Consistent with this idea, the correlation between externalizing symptoms in Wave 1 and Wave 7 was significantly greater than the corresponding correlation for internalizing symptoms, (r = .48 vs. r = .31, ZPF = 2.19, p = .03). Similarly, the correlation between externalizing symptoms in Wave 1 and Wave 7 was significantly greater than the corresponding correlation for dating satisfaction, (r = .48 vs. r = .22, ZPF = 2.95, p = .003).

The differences in the pattern of results may also have occurred because different facets of romantic experiences are associated with different indices of adjustment. For example, the stress and coping model was derived as an explanation for internalizing symptoms and depression, not externalizing symptoms (Davila, 2008). Perhaps alternative mechanisms, such as partner characteristics are associated with externalizing behavior, such as delinquency. Adolescents who engage in delinquent behavior are likely to have delinquent partners (Lonardo, Giordano, Longmore, & Manning, 2009), and having such a romantic partner may lead to delinquent behavior (Haynie, Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2005).

The pattern of findings for externalizing symptoms is also distinct from prior work with this sample on romantic involvement (Furman & Collibee, 2014). In prior work, the presence of a romantic relationship was associated with more externalizing symptoms in adolescence, but less in young adulthood. In other words, the links between romantic involvement and externalizing symptoms vary by age, whereas the links between romantic relationship qualities and externalizing do not. Perhaps the negative links in adolescence are accounted for by the typical quality of these romantic relationships. As romantic relationships improve in quality developmentally, the associations between romantic involvement and adjustment may also change such that romantic involvement becomes protective in young adulthood.

Limitations and Future Directions

In the present study, we examined the longitudinal developmental course of associations between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment from adolescence into young adulthood. However, we only examined the concurrent associations at the different ages. Developmental task theory hypothesizes that once romantic relationships are a salient developmental task, quality of functioning in the task (i.e., romantic relationship qualities) should predict future adaptation (Roisman, et al. 2004). Future research should examine such longitudinal associations. Studies examining whether romantic relationship qualities are predictive of success in other subsequent developmental tasks would be particularly informative.

Longitudinal studies would also help test potential alternative explanations for the present associations, as the concurrent nature of the present study does not address the directionality of the links. We focused on how romantic relationship qualities may be linked to adjustment, but the links may also go from adjustment to romantic relationship qualities, which would also be consistent with developmental task theory. Indeed, we examined and found the expected associations from adjustment to romantic qualities as well, suggesting that these links may go in either direction, which is consistent with some extant literature (Davila, Stroud, & Starr, 2009). In fact, several of our explanations of the associations also were based on the idea that adjustment may affect the quality of romantic relationships (e.g., internalizing symptoms affecting relationship qualities). Further work should aim to better understand these potential bidirectional processes. On a related note, the various relationship qualities were correlated with one another, as were the various adjustment indices. An important next step would be to better understand which romantic qualities may uniquely be related to specific adjustment indices.

Third variable explanations such as partner effects may also be responsible for patterns of findings. Additionally, although the present study examined the developmental course of these links over almost a decade, expanding the age range being studied would be an important next step. For example, the links between romantic quality and adjustment may become even stronger as young adults begin cohabitating or get married, as links between marriage and well-being are well established (Williams, Frech, & Carlson, 2010)

Finally, we have demonstrated that the quality of romantic relationships is predictive of adjustment even when controlling for the presence of a romantic relationship. Future work should extend these findings and explore if the normative quality of romantic relationships in adolescence and young adulthood may partially account for the links between romantic involvement and adjustment in the literature.

Despite these limitations, the present study contributes significantly to the field by providing the first examination of the developmental course of links between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment over a nine year span. Taken together, the present study provides evidence for a developmental task theory of romantic relationships. Perhaps more importantly, it offers consistent evidence of associations between romantic relationship qualities and adjustment across development. Indeed, higher romantic quality was commonly associated with adjustment in adolescence, and these links are magnified in young adulthood as romantic relationships become a salient developmental task.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by Grant 050106 from the National Institute of Mental Health (W. Furman, P.I.) and Grant 049080 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (W. Furman, P.I.). Appreciation is expressed to the Project Star staff for their assistance in collecting the data, and to the Project Star participants and their partners, friends and families.

References

- Achenbach TM. Child behavior checklist/4-18. University of Vermont; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the young adult self-report and young adult behavior checklist. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter L, Bullis C. Turning points in developing romantic relationships. Human Communication Research. 1986;12:469–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1986.tb00088.x. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery D. Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens JT. Principles and procedures of exploratory data analysis. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:131–160. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.2.2.131. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly JA, McIsaac C. Romantic relationships in adolescence. In: Lerner R, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3rd Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. pp. 104–151. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J. Depressive symptoms and adolescent romance: Theory, research, and implications. Child Development Perspectives. 2008;2:26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00037.x. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Stroud CB, Starr LR. Depression in couples and families. In: Gotlib I, Hammen C, editors. Handbook of depression. 2nd Guilford; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 467–491. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J. Romantic relationships and mental health in emerging adulthood. In: Fingerman KL, Cui M, editors. Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Eggert LL, Herting JR, Thompson EA. The drug involvement scale for adolescents (DISA) Journal of Drug Education. 1996;26:101–130. doi: 10.2190/EQ6J-D4GH-K4YD-XRJB. doi: 10.2190/EQ6J-D4GH-K4YD-XRJB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, White HR, Catalano RF. Romantic relationships and substance use in early adulthood: An examination of the influences of relationship type, partner substance use, and relationship quality. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:153–167. doi: 10.1177/0022146510368930. doi: 10.1177/0022146510368930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford DH, Lerner RM. Developmental systems theory: An integrative approach. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Collibee C. A matter of timing: Developmental theories of romantic involvement and psychosocial adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26:1149–1160. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000182. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Shaffer L. The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Wehner EA. Dating History Questionnaire. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 1992. Unpublished measure. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Wehner EA. Adolescent romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1997;1997:21–36. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219977804. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219977804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Winkles JK. Transformations in heterosexual romantic relationships across the transition into adulthood: “Meet me at the bleachers… I mean the bar. In: Laursen B, Collins WA, editors. Relationship pathways: From adolescence to young adulthood. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2011. pp. 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Manning WD, Longmore MA, Flanigan CM. Developmental shifts in the character of romantic and sexual relationships from adolescence to young adulthood. In: Booth A, Brown SL, Landale NS, Manning WD, McHale SM, editors. Early adulthood in a family context. Springer; New York, NY: 2012. pp. 133–164. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the self-perception profile for adolescents. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Giordano PC, Manning WD, Longmore MA. Adolescent romantic relationships and delinquency involvement. Criminology. 2005;43:177–210. doi: 10.1111/j.0011-1348.2005.00006.x. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Zeifman D. Sex and the psychological tether. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Attachment processes in adulthood: Advances in personal relationships. Jessica Kingsley; London: 1994. pp. 151–178. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2001. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2002. NIH Publication No. 02-5105. [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K, Udry JR. You don't bring me anything but down: Adolescent romance and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:369–391. doi: 10.2307/2676292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamp Dush CM, Amato PR. Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22:607–627. doi:10.1177/0265407505056438. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantagne AS, Furman W. Emerging qualities of romantic relationships from adolescence to adulthood. 2015. Unpublished manuscript.

- Levesque RJ. The romantic experience of adolescents in satisfying love relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1993;22:219–251. doi: 10.1007/BF01537790. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Jorgensen TD, Lang KM, Moore EWG. On the joys of missing data. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2014;39:151–162. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst048. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonardo RA, Giordano PC, Longmore MA, Manning WD. Parents, friends, and romantic partners: Enmeshment in deviant networks and adolescent delinquency involvement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:367–383. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9333-4. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9333-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy B, Casey T. Love, sex, and crime: Adolescent romantic relationships and offending. American Sociological Review. 2008;73:944–969. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300604. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick CM, Kuo SIC, Masten AS. Developmental tasks across the lifespan. In: Fingerman KL, Berg CA, Smith J, Antonucci TC, editors. Handbook of lifespan development. Springer; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Meeus W, Branje S, Overbeek GJ. Parents and partners in crime: A six-year longitudinal study on changes in supportive relationships and delinquency in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:1288–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00312.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeus WH, Branje SJ, van der Valk I, de Wied M. Relationships with intimate partner, best friend, and parents in adolescence and early adulthood: A study of the saliency of the intimate partnership. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31:569–580. doi: 10.1177/0165025407080584. [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB. Multilevel modeling analysis of diary-style data. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, editors. Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. Guilford; New York, NY: 2012. pp. 357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:141–151. doi: 10.2307/351302. [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek G, Ha T, Scholte R, de Kemp R, Engels RC. Brief report: Intimacy, passion, and commitment in romantic relationships—Validation of a ‘triangular love scale’ for adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.12.002. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. doi:10.3102/10769986031004437. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R. HLM5: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Scientific Software International; Chicago, IL: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Booth-LaForce C, Cauffman E, Spieker S. The developmental significance of adolescent romantic relationships: Parent and peer predictors of engagement and quality at age 15. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1294–1303. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9378-4. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9378-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, Tellegen A. Salient and emerging developmental tasks in the transition to adulthood. Child Development. 2004;75:123–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00658.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C, Powell HL, Givertz M, Brackin A. Symptoms of depression, relational quality, and loneliness in dating relationships. Personal Relationships. 2003;10:25–36. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00034. [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. Testing theories of romantic development from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence of a developmental sequence. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:519–531. doi: 10.1080/01650250344000145. [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW, Barrett AE. Nonmarital romantic relationships and mental health in early adulthood: Does the association differ for women and men? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:168–182. doi: 10.1177/0022146510372343. doi: 10.1177/0022146510372343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Starr LR, Davila J, Stroud CB, Li PCC, Yoneda A, Hershenberg R, Miller MR. Love hurts (in more ways than one): Specificity of psychological symptoms as predictors and consequences of romantic activity among early adolescent girls. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68:403–420. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20862. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen E, Smith LB. Dynamic systems theories. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, Lerner RM, editors. Theoretical models of human development: Vol. 1. Handbook of child psychology. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 258–312. Series Ed. Vol. Ed. [Google Scholar]

- van Dulmen MH, Goncy EA, Haydon KC, Collins WA. Distinctiveness of adolescent and emerging adult romantic relationship features in predicting externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:336–345. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9245-8. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh DP, Haugen PT, Widman L, Darling N, Grello CM. Kissing is good: A developmental investigation of sexuality in adolescent romantic couples. Sexuality Research & Social Policy. 2005;2:32–41. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2005.2.4.32. [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Frech A, Carlson DL. Marital status and mental health. In: Scheid TL, Brown TN, editors. A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2010. pp. 306–320. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Siebenbruner J, Collins WA. Diverse aspects of dating: Associations with psychosocial functioning from early to middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:313–336. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0410. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]