Abstract

Background

Previous studies of CF treatments have shown suboptimal adherence, though little has been reported regarding adherence patterns to ivacaftor. Electronic monitoring (EM) of adherence is considered a gold standard of measurement.

Methods

Adherence rates by EM were prospectively obtained and patterns over time were analyzed. EM-derived adherence rates were compared to pharmacy refill history and self-report.

Results

12 subjects (age 6-48 years; CFTR-G551D mutation) previously prescribed ivacaftor were monitored for a mean of 118 days. Overall adherence by EM was 61%(SD=28%) and decreased over time. Median duration between doses was 16.9 hours (IQR 13.9-24.1 hours) and increased over time. There was no correlation between EM-derived adherence and either refill history (84%, r=0.26, p=0.42) or self-report (100%, r=0.40, p=0.22).

Conclusions

Despite the promising nature of ivacaftor, our data suggest adherence rates are suboptimal and comparable to other prescribed CF therapies, and more commonly used assessments of adherence may be unreliable.

Keywords: adherence, potentiator, pediatric

1. Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common life-shortening genetic disease among Caucasians with an incidence of one per 3500 births in the United States[1]. Early treatment efforts exclusively targeted disease symptoms in an attempt to slow its progression, and with advancements in available therapies the median age of survival has increased to 37 years. However, these same advancements also contribute to the complexity of managing a time-consuming and often burdensome treatment regimen. Moreover, treatment burden is likely to increase throughout a patient's lifetime, as patients develop comorbidities such as CF-related diabetes mellitus and complex bacterial infections as their illness progresses. There is now a therapy available to directly target the underlying cause of CF, namely the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein. CFTR, when not synthesized correctly or in enough quantity, is responsible for the buildup of abnormally thick and sticky mucus in the lungs, pancreatic insufficiency and other disease manifestations. This results in a progressive lung disease caused by recurrent respiratory infections and is the leading cause of death in CF[2].

In 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration approved ivacaftor, the first CFTR potentiator therapy for patients with CF ages 6 years and older who have a CFTR-G551D mutation. This genotype-specific therapy has subsequently been expanded to include patients with a number of additional CFTR mutations that result from gating and conduction defects. Ivacaftor represents a fundamental shift in CF treatment, targeting the cause of disease rather than its downstream manifestations. Initial findings have been promising, with sustainable improvement in CFTR function, lung function, quality of life and nutritional status[3-5]. With ongoing research using a similar genotype-targeted approach, there is a real potential to restore function to the most common CFTR mutations in CF[6].

In light of these recent advancements, adherence to prescribed regimens remains a serious concern. Consistent with suboptimal adherence rates reported in other chronic illness literature, studies in CF have found adherence rates ranging from 22% to 90% across treatment components and methods of adherence measurement[7-9]. Multiple studies have shown that higher adherence has been associated with fewer and shorter hospitalizations and less pulmonary exacerbations[10-12]. Notably, the landmark study[3] by Ramsey and colleagues reported adherence rates of 89-91% for ivacaftor, with estimates based primarily on patient-report and pill counts. While adherence rates are often high in clinical trials, frequently this fails to fully translate into clinical practice.

While initial findings support the efficacy of ivacaftor, there have been few systematic studies of adherence rates and associated factors for this new class of medication. A screening of early pharmacy refill data at our center (Source: Vertex Pharmaceuticals) and anecdotal clinical experience suggests non-adherence may be a factor associated with poor clinical response to therapy. Our prospective, observational study had two primary aims: 1) to document adherence rates and patterns objectively for ivacaftor by utilizing electronic monitoring; 2) to compare the gold standard of electronic monitoring with self-report and pharmacy refill data, modalities that are more commonly used in clinics. We hypothesized, that despite the benefit and simplicity of this intervention, adherence rates would be similar to those of standard CF therapies. We also hypothesized that a significant difference in adherence rates by measurement method would be observed, such that rates of self-reported adherence would be higher compared to those obtained from electronic monitoring or pharmacy refill data.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Sample Selection and Procedure

Patients were recruited from two accredited CF centers, one pediatric (250 total patients) and one adult (140 total patients). Patients included in the study met the following criteria: confirmed diagnosis of CF with the CFTR-G551D mutation (the only approved mutation at the time of the study), ages 6 years and older, and had been prescribed ivacaftor for at least one month. Patients were excluded if there was a provider-initiated reason for them not to take their ivacaftor or if there was a developmental disability that prevented them from effectively monitoring their adherence or completing surveys.

Eligible patients were approached by trained research staff during routine CF clinic visits. Patients who provided written consent to participate in the study were given an electronic monitoring (EM) device and instructed to use the device to dispense their ivacaftor for the duration of the study. Self-report measures of medication adherence were completed at time of enrollment and 3-4 months later during a routine CF clinic visit. Data from the EM device were downloaded, and patients received feedback on their adherence data. Patients who demonstrated non-adherence and expressed interest were referred for outpatient adherence promotion intervention. Medical chart review was conducted to extract patient demographic information (e.g., age, gender, duration of prescribed ivacaftor), forced expiratory volume in 1 second as a percent predicted [FEV1PP] for age and height, and body mass index [BMI]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (2013-5341) and the University of Cincinnati Medical Center (2013-5341).

2.2. Primary Adherence Measure – Electronic Monitors

The Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS®; AARDEX Ltd. Zug, Switzerland), which has been used extensively in research studies in both adult and pediatric samples [13-15], was used to objectively monitor adherence. MEMS® mimics a traditional pill bottle in both appearance and utility, and tracks the date and time of each bottle opening. Graphic feedback is provided in the form of calendars and time plots at each data download. The number of bottle openings per day are indicated in the calendar feedback, while the frequency of time points for bottle openings are indicated in time plots.

EM data were used to calculate overall adherence rates, weekly adherence rates, and mean duration between doses. For each patient, the overall adherence rate was defined as , and the weekly adherence rate was defined as . The weeks were counted from the first recorded date by the MEMS®. If the last week contained only one day, it was excluded from the analysis of weekly adherence. Appropriate adjustments were applied for half days when counting the doses that should have been taken in the denominator of the formula.

Duration between doses was also obtained. For each patient, the mean over the total monitoring period was defined as the overall mean duration between doses. The mean of every seven days was defined as the weekly mean duration between doses. Many subjects took “drug holidays” for several days at a time, resulting in prolonged intervals between doses. Intervals between doses greater than 72 hours were truncated at 72 hours (both overall and weekly).

2.3. Secondary Adherence Measures

Secondary medication adherence rates were documented using self-report and pharmacy refill data. Self-report adherence data was obtained using The Self-Reported Treatment Adherence & Barriers Assessment[16]. The current version, used with permission from Dr. Quittner, includes 57 items that assesses the frequency and duration of each CF treatment component and has demonstrated adequate 1-year test-retest reliability[17].

Prescription refill data were obtained from each patient's pharmacy over the study period. Adherence rates were calculated using the medication possession ratio (MPR), a widely used measurement of pharmacy-obtained adherence data. The MPR is calculated by dividing the total amount of medication obtained by the patient by the total amount of prescribed medication. Pharmacy data were measured from the fill date immediately prior to enrollment to the fill date immediately prior to the end of the study.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and frequency/percentage for categorical variables, were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics as well as the overall adherence rate and mean duration between doses.

The primary analysis of this study modeled the trajectory pattern of the EM-derived adherence over time. Mixed effects models were used to model the weekly adherence rate and mean duration between doses over time. In the mixed effects model, the fixed effect accounted for the variation over time with restricted cubic spline to also account for the possible nonlinear trend. The random effect accounted for the individual subject's variation from the population means. First order autoregressive covariance structure was used to account for the correlation between the observations within each subject. Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) was used to select the best models. The effects of best FEV1PP and weeks prescribed ivacaftor before the first visit were evaluated by including the factors as covariates in the models.

For our secondary analysis, the level of agreement between EM-derived adherence and MPR and self-reported adherence were evaluated using Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC, USA) and R 3.1.0 (R Core Team, 2014) were used for all the analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Sixteen CF patients met inclusion criteria and 12 patients aged 6-48 years were included in the study (Figure 1). Fifty percent of patients were female, and all were identified as Caucasian. On average, patients had been prescribed ivacaftor for 55 weeks (range 11-89 weeks) prior to enrollment (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of patient enrollment.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age at first visit, years | 20.8 (9.9) | 6.7-48.4 |

| Weeks prescribed ivacaftor prior to study | 55.3 (24.6) | 11.9-89.6 |

| Best FEV1 percent predicteda | 100.7 (18.2) | 70.0-136.0 |

| BMI at first visit (kg/m2)b | 23.1 (3.8) | 17.7-30.3 |

BMI = body mass index; FEV = forced expiratory volume; SD = standard deviation.

Best FEV1 defined by highest FEV1 Percent Predicted in the prior 12 months

Absolute BMI was used, as most patients were >18 years of age, and percentiles are not routinely used for adults.

3.2. Adherence Rates

Overall, these 12 patients had an average monitoring period of 118 days (SD=35 days) (Table 2). The overall EM-derived adherence rates ranged from 4% to 99% with mean (SD) = 61% (28%). Adherence rates by MPR ranged from 13% to 124% with mean (SD) = 84% (31%). With one exception, self-reported adherence was 100% at both points of measurement.

Table 2.

Adherence rates by measurement method (n=12)

| Measurement | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring duration, days | 117.5 (35.2) | 35-182 |

| Self-report | 100%a | 14-100% |

| Pharmacy refill history (MPR) | 84% (31) | 13-124% |

| Electronic monitoring (EM) | 61% (28) | 4-99% |

| Mean duration between doses, hours (raw data) | 19.8 (13.9 – 28.7)b | 12.1-352.8 |

| Mean duration between doses, hours (with truncation) | 16.9 (13.9 – 24.1)b | 12.1-43.7 |

11/12 patients reported 100% adherence, the outlier of 14% was not used in calculation of the mean

Median (IQR) are reported instead of mean (SD).

Based on EM data, overall mean duration between doses ranged from 12.1 to 352.8 hours with median (IQR) = 19.8 (13.9-28.7) hours (Table 2). After truncating the time between doses to 72 hours, the overall mean duration between doses ranged from 12.1 to 43.7 hours with median (IQR) = 16.9 (13.9-24.1) hours, mean (SD) = 19.9 (8.98) hours.

3.3. Adherence Patterns Over Time

Weekly adherence rates varied substantially between the subjects and over time (Figure 2a). Among different models for the time trend (linear, quadratic, restricted cubic spline), the simple linear model was the best model based on AIC, finding adherence decreased over time at a rate of 1.93% per week. The weekly mean duration between doses calculated with truncation at 72 hours was used for regression analysis. Similar to the approach for the weekly adherence rate, the weekly mean duration between doses was best fitted with a restricted cubic spline with four knots (chosen at 5%, 35%, 65% and 95% percentiles of the predictor variable weeks) (Figure 2b). The mean duration between doses increased with time and the increase accelerated at about 7 weeks. Neither best FEV1PP nor weeks on ivacaftor prior to the study significant affected weekly adherence rate or mean duration between doses.

Figure 2.

Adherence patterns over time. Individual subject data (from EM) is represented by the thin, multicolored lines. A: Weekly adherence rates are shown over time, with the regression line, as determined with a linear mixed-effect model is shown in thick, dark blue. B: Duration of time between doses, using adjusted values, are shown over time. The regression line, as determined with a cubic spline with 4 knots mixed-effect model, is shown in dotted-blue.

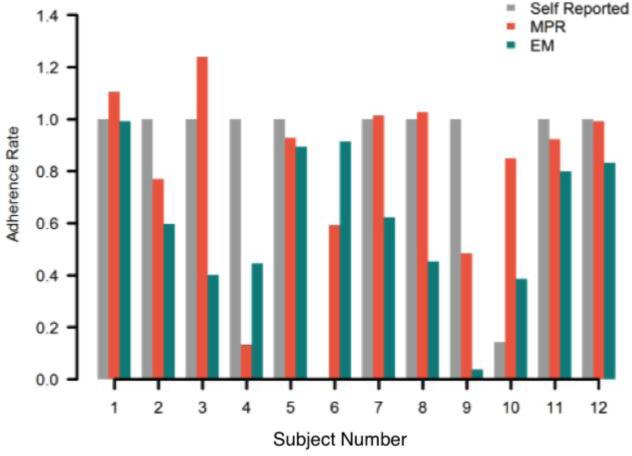

3.4. Comparison of Adherence Measures

Individual subjects demonstrated wide variability in regards to the different measures of adherence (Figure 3). There was no significant correlation (rs=0.26, p=0.42) or agreement (ICC=0.26, p=0.14) between overall EM-derived adherence rates and MPR. There was also no significant correlation (rs=0.40, p=0.22) or agreement (ICC=0.14, p=0.23) between overall EM-derived adherence rates and self-reported adherence.

Figure 3.

Individual adherence rates by measurement method

4. Discussion

In summary, by using electronic monitoring, we objectively quantified adherence rates and patterns in this new class of medications. Consistent with our first hypothesis, average overall adherence to ivacaftor was suboptimal at 61%, compared to their prescribed regimen and quite variable across subjects. This finding is in line with a recent study of 24 adolescents with CF that revealed an overall adherence rate of 65% ± 28% to nebulized medications using EM data[18]. EM data also revealed tremendous variability in time between doses of ivacaftor, such that the median duration was 4.9 hours longer than the prescribed 12-hour interval. When analyzing the data over time, we found that adherence decreased at a rate of 1.9% per week. The average time between doses also increased over time in a non-linear pattern. Overall, our findings suggest that despite the promising nature of this class of medications, non-adherence to ivacaftor is a significant issue and may worsen over time.

Obtaining reliable and accurate adherence data has significant implications for both patients and care providers. Unreliable measurement methods impede a provider's ability to proactively address recognized barriers to medication adherence (e.g., side effects, health-related quality of life)[9]. In the absence of objective information about the prevalence and patterns of treatment non-adherence, providers often rely on their clinical judgment and prior experience to differentiate between a lack of medication efficacy and non-adherence when a patient is not responding to treatment as expected. Furthermore, this medication was extensively studied in terms of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, with a 12-hour dosing schedule found to be ideal[19]. Thus, patients are being undertreated when they are non-adherent and are less likely to attain the benefits seen in prior studies[3-5].

Consistent with our second hypothesis, there was no convergence between EM-derived adherence rates compared to pharmacy refill history or self-reported adherence – the most common clinically used measures of adherence. This further emphasizes the potential shortcomings of relying on less objective measures of adherence that may be an overestimate of true adherence rates. Electronic monitoring is the only measure of adherence that can observe patterns over time, which may provide insight into human behavior and the need for earlier intervention. However, recognizing the constraints of using EM exclusively in a clinical setting and accounting for the multiple types of therapies in CF (e.g. oral medications, nebulized medications, airway clearance therapies), a multi-method approach to measuring treatment adherence in CF is still recommended.[7]

It is important to recognize that barriers to adherence are different, and often evolving, among patients. Barriers to adherence were assessed with our self-report survey, however, only one patient identified any barrier to adherence on this survey (“insurance does not cover my medication”). During follow-up phone conversations, we verbally asked about any barriers to all the subjects, and 1 additional subject elicited a barrier (I do not like how the medication makes me feel”). It was not until revealing individual adherence results to the subjects and having lengthy conversations, that barriers were then admitted, with “I forgot to take it” being the most common. As obtaining this data was not standardized, and required individualized conversations and often significant probing for information, this data was not further analyzed. Anecdotally, this is further support against the use of self-report as a sole method of adherence measurement.

Our study had limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, our sample was relatively small, included a wide-range of ages, and only included 75% of eligible patients. Yet, at the time of this study, only patients with the CFTR-G551D mutation were eligible for ivacaftor, and our total population on medication was comparable to the national average based on the size of our CF centers. While our patients were relatively healthy in comparison to other patients with CF, it is notable that patients with gating mutations often have a milder phenotype. Second, there is the potential for patients to increase their adherence prior to their clinic visits (e.g., “white coat adherence”). However, it should not pose a major threat to validity as patients were monitored over an extensive period of time, and past research has shown that reactivity to EM decreases significantly over time[9]. Finally, it should be acknowledged that patients with chronic illness and multiple medications may take out their pills from their bottles without intention to immediately take them, or use weekly pill boxes to simplify daily dosing with oral medications. Information about pill boxes was gathered at the time of enrollment, and two patients identified using pill boxes, both agreeing to use the EM bottle while enrolled in the study. We had no way to confirm that taking a pill from the bottle resulted in subsequent swallowing of the pill; however, there is no realistic way to monitor this, and, if it were the case, our data would actually be an over-estimate of adherence.

In the context of this non-clinical trial in a clinical setting, in a group of patients that we assume should be highly motivated, non-adherence to ivacaftor demonstrated to be significant and variable. Non-adherence in CF is likely to have a negative impact on patients’ health and quality of life, and needs to be addressed early on if identified. Although electronic monitors are a gold-standard in research and not typically used in routine clinical care, this group of patients is relatively small and the cost of monitors is trivial when compared to the cost of medication. As newer medications in this class are on the horizon for patients with CF, and we expect them to be prescribed to more patients, objective monitoring can help identify non-adherence patterns and allow earlier and individualized intervention to promote adherence.

Highlights.

Treatment adherence remains a significant issue in patients with CF

Novel medications, while promising, are not immune to non-adherence

Adherence patterns to ivacaftor are similar to other CF medications

Overall adherence decreases over time, as does time between doses

Interventions promoting adherence may be as important as developing novel therapies

Acknowledgements

Guarantor Statement: Dr. Siracusa takes responsibility for the content of this manuscript, including the data and analysis.

Role of the sponsors: Electronic monitors and software were funded by the aforementioned NIH T-32 grant.

Funding/support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant 5T32HD068223-02].

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- EM

electronic monitoring

- FEV1PP

forced expiratory volume in 1 second percent predicted

- MEMS

Medication Events Monitoring System

- MPR

medication possession ratio

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Clancy and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center has obtained research contract funding from Vertex Pharmaceuticals to conduct clinical trials in CF patients, that were not directly related to this present study. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

Prior presentation: Parts of this study have been presented in abstract/poster form at the 28th Annual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference, October 9-11, 2014, Atlanta, GA.

Author contributions: CMS had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. CMS, LB, NZ, JPC, and DD contributed to the study concept and design; CMS, YW, and NZ contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data; CMS, JPC, and DD contributed to the interpretation of the data; CMS, JR, LB, YW, NZ, JPC and DD contributed to drafting of the manuscript; CMS, JR, LB, YW, NZ, JPC and DD contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: This work was supported under a training grant funded by the National Institutes of Health [Grant 5T32HD068223-02]. Dr. Clancy and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center has obtained research contract funding from Vertex Pharmaceuticals to conduct clinical trials in CF patients, that were not directly related to this present study

Other contributions: We thank the patients and parents at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and the University of Cincinnati Medical Center for their participation in the study; the CF physicians at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and University of Cincinnati (Raouf Amin, Lisa Burns, Barb Chini, JP Clancy, Patricia Joseph, Gary McPhail and Bruce Trapnell), for providing care to patients; Erin Brockman, Lorrie Duan and Traci Jerkins, for help with recruitment and participation in study visits; Alexandra Quittner, for use of her questionnaires; and Avani Modi and Denise Wetzel, for critical review of the manuscript prior to submission.

References

- 1.Kosorok MR, Wei WH, Farrell PM. The incidence of cystic fibrosis. Statistics in medicine. 1996;15(5):449–62. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960315)15:5<449::AID-SIM173>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faro A, Michelson P, Ferkol T. Pulmonary Disease in Cystic Fibrosis. In: Wilmott B, Bush, Chernick, Deterding, Ratjen, editors. Kendig and Chernick's Disorders of the Respiratory Tract in Children. 8 ed. Elsevier; Philadephia, PA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, Tullis E, Bell SC, Drevinek P, et al. A CFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(18):1663–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowe SM, Heltshe SL, Gonska T, Donaldson SH, Borowitz D, Gelfond D, et al. Clinical mechanism of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator potentiator ivacaftor in G551D-mediated cystic fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;190(2):175–84. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0703OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heltshe SL, Mayer-Hamblett N, Burns JL, Khan U, Baines A, Ramsey BW, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Cystic Fibrosis Patients With G551D-CFTR Treated With Ivacaftor. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2014 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle MP, Bell SC, Konstan MW, McColley SA, Rowe SM, Rietschel E, et al. A CFTR corrector (lumacaftor) and a CFTR potentiator (ivacaftor) for treatment of patients with cystic fibrosis who have a phe508del CFTR mutation: a phase 2 randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Respiratory medicine. 2014;2(7):527–38. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Modi AC, Lim CS, Yu N, Geller D, Wagner MH, Quittner AL. A multi-method assessment of treatment adherence for children with cystic fibrosis. Journal of cystic fibrosis : official journal of the European Cystic Fibrosis Society. 2006;5(3):177–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quittner AL, Espelage DL, Ivers-Landis CE, Drotar D. Measuring adherence to medical treatments in childhood chronic illness: considering multiple methods and sources of information. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2000;7:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rappoff M. Adherence to Pediatric Medical Regimens. Springer; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briesacher BA, Quittner AL, Saiman L, Sacco P, Fouayzi H, Quittell LM. Adherence with tobramycin inhaled solution and health care utilization. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2011;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nasr SZ, Chou W, Villa KF, Chang E, Broder MS. Adherence to dornase alfa treatment among commercially insured patients with cystic fibrosis. Journal of medical economics. 2013;16(6):801–8. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.787427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wertz DA, Chang CL, Stephenson JJ, Zhang J, Kuhn RJ. Economic impact of tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis in a managed care population. Journal of medical economics. 2011;14(6):759–68. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.621004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rapoff MA, Belmont JM, Lindsley CB, Olson NY. Electronically monitored adherence to medications by newly diagnosed patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;53(6):905–10. doi: 10.1002/art.21603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maikranz JM, Steele RG, Dreyer ML, Stratman AC, Bovaird JA. The relationship of hope and illness-related uncertainty to emotional adjustment and adherence among pediatric renal and liver transplant recipients. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(5):571–81. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modi AC, Lim CS, Yu N, Geller D, Wagner MH, Quittner AL. A multi-method assessment of treatment adherence for children with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 2006;5(3):177–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quittner AL, Modi AC, Lemanek KL, Ievers-Landis CE, Rapoff MA. Evidence-based assessment of adherence to medical treatments in pediatric psychology. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2008;33(9):916–36. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm064. discussion 37-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quittner AL, Drotar D, Ivers-Landsi CE, Seinder D, Slocum N, Jocobson J. Adherence to medical treatments in adolescents with cystic fibrosis: the development and evaluation of family-based interventions. In: Drotar D, editor. Promoting adherence to medical treatment in childhood chronic illness: Concepts, methods, and interventions. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ball R, Southern KW, McCormack P, Duff AJ, Brownlee KG, McNamara PS. Adherence to nebulised therapies in adolescents with cystic fibrosis is best on week-days during school term-time. Journal of cystic fibrosis : official journal of the European Cystic Fibrosis Society. 2013;12(5):440–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Accurso FJ, Rowe SM, Clancy JP, Boyle MP, Dunitz JM, Durie PR, et al. Effect of VX-770 in persons with cystic fibrosis and the G551D-CFTR mutation. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(21):1991–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]