Abstract

Background

Neurogenesis continues throughout life in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Chronic treatment with monoaminergic antidepressant drugs stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis, and new neurons are required for some antidepressant-like behaviors. Electroconvulsive seizures (ECS), a laboratory model of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), robustly stimulate hippocampal neurogenesis.

Hypothesis

ECS requires newborn neurons to improve behavioral deficits in a mouse neuroendocrine model of depression.

Methods

We utilized immunohistochemistry for doublecortin (DCX), a marker of migrating neuroblasts, to assess the impact of Sham or ECS treatments (1 treatment per day, 7 treatments over 15 days) on hippocampal neurogenesis in animals receiving 6 weeks of either vehicle or chronic corticosterone (CORT) treatment in the drinking water. We conducted tests of anxiety- and depressive-like behavior to investigate the ability of ECS to reverse CORT-induced behavioral deficits. We also determined whether adult neurons are required for the effects of ECS. For these studies we utilized a pharmacogenetic model (hGFAPtk) to conditionally ablate adult born neurons. We then evaluated behavioral indices of depression after Sham or ECS treatments in CORT-treated wild-type animals and CORT-treated animals lacking neurogenesis.

Results

ECS is able to rescue CORT-induced behavioral deficits in indices of anxiety- and depressive-like behavior. ECS increases both the number and dendritic complexity of adult-born migrating neuroblasts. The ability of ECS to promote antidepressant-like behavior is blocked in mice lacking adult neurogenesis.

Conclusion

ECS ameliorates a number of anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors caused by chronic exposure to CORT. ECS requires intact hippocampal neurogenesis for its efficacy in these behavioral indices.

Keywords: ECT, ECS, hippocampus, neurogenesis, neuroplasticity, antidepressant

Introduction

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is the most effective treatment for severe depressive disorders, particularly melancholic depression[1, 2]. Successful ECT treatment is associated with normalization of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis abnormalities in this patient population [3, 4]. The hippocampus is a limbic brain region that is particularly sensitive to excitotoxic insults that arise from elevated levels of circulating glucocorticoids, and it plays a key role in the stress response by providing negative feedback inhibition over the HPA axis[5-7]. These findings may be clinically relevant because volumetric changes have been noted in the hippocampus of patients with major depressive disorder[8, 9]. In the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, new granule cells are continuously generated throughout adulthood. The process of adult hippocampal neurogenesis includes the proliferation of radial glia-like glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive neural progenitor cells and the differentiation of these cells into migrating doublecortin (DCX)-positive neuroblasts. These neuroblasts mature into young granule cells, which integrate into the existing hippocampal circuitry. New neurons have distinct cellular and physiological properties including an increased propensity for excitability and plasticity, which may contribute to their ability to exert influence over mood-related hippocampal circuits[10, 11].

Hippocampal neurogenesis is stimulated by chronic treatment with monoaminergic antidepressant drugs. Many research studies have concluded that adult neurogenesis does not contribute to development of depressive-like behaviors per se. However, adult-born neurons may mediate several behavioral effects of pharmacological antidepressant treatments[11-14]. Electroconvulsive seizures (ECS) are a laboratory model of ECT, which stimulate hippocampal neurogenesis [15-18], and counteract the deleterious effects of glucocorticoids on neurogenesis[19]. ECS-induced antidepressant-like behavior and ECS-induced increases in neurogenesis have led to speculation that newborn neurons contribute to the behavioral effects of ECT [20]. However, evidence that newborn neurons are required for ECS to exert antidepressant efficacy has not yet been demonstrated. Here, we investigate this hypothesis in a neuroendocrine mouse model of depression. This model utilizes administration of chronic corticosterone (CORT), and was designed to mimic the HPA axis dysfunction and behavioral disturbances observed in depressed patients[12, 21]. The model reliably induces a depression-like state in rodents[12].

Materials and methods

Corticosterone administration

CORT (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in vehicle (0.45% hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, β-CD)(Sigma-Aldrich), and CORT (35 μg/ml/d) or vehicle was administered to animals ad libitum via the drinking water. Bottles were covered with foil to protect them from light and solutions were freshly made and changed every third day to prevent possible degradation.

ECS treatment

The ECS paradigm consisted of 7 ECS sessions across a 15d period delivered with an Ugo Basile pulse generator (model #57800-001, shock parameters: 100 pulse/s frequency, 3 ms pulse width, 1s shock duration and 50 mA current). Mice were administered inhaled isoflurane anesthesia prior to ECS sessions, and remained anesthetized for the procedure. The stimulation parameters were chosen because they reliably induced tonic-clonic convulsions, caused robust antidepressant behavior and increased hippocampal neurogenesis in our laboratory. No differences in latency to convulsion or severity were observed between genotype or treatment groups, and all study animals survived the procedure (data not shown).

Suppression of neurogenesis

To suppress neurogenesis, we utilized mice expressing herpes simplex thymidine kinase (HSV-tk) under control of the human glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) gene promoter (hGFAPtk mice). This pharmacogenetic model allows new neurons to be selectively ablated in adulthood[22]. hGFAPtk animas were maintained on a C57Bl6/J background and derived from female hGFAPtk heterozygote X male C57Bl6/J animals (Jackson Labs). In this transgenic model, HSVtk is selectively expressed in GFAP-expressing cells. In the presence of valganciclovir (VGCV), the L-valyl ester of ganciclovir, only those actively dividing GFAP-expressing cells (e.g. neural progenitors; not astrocytes) are ablated[22]. VGCV (Roche) was administered in the animals’ chow (15mg/kg/d). VGCV-fed wild-type (Ctrl) and hGFAPtk transgenic (NG-) animals were used for these studies. Numerous previous studies have shown that this dose of VGCV reliably leads to absence of all DCX+ cells in the hippocampus. In this study, absence of neurogenesis was confirmed in NG- mice by assessing coronal sections spanning the length of the hippocampus for absence of expression of doublecortin (DCX), a marker of migrating neuroblasts, in both NG-/Sham and NG-/ECS study animals (data not shown).

Behavior Tests

To assess for a depressive-/anxiety-like state we examined several previously described measures [14]. Specifically, we assessed behavior in the novelty suppressed feeding test (NSF) and the splash-grooming test. We also conducted an investigation of the animals’ coat state. These specific tests were chosen based on previous studies demonstrating these measures as robustly affected in the neuroendocrine CORT model and as dependent on neurogenesis for an antidepressant response [12-14].

Briefly, the NSF is a conflict anxiety test where motivation to eat competes with fear of a brightly lit arena. Decreased latency to feed is indicative of less anxiety-/depressive-like behavior, while increased latency to feed is indicative of higher anxiety-/depressive-like behavior. Chronic, but not acute administration of monoaminergic antidepressant drugs decreases the latency to feed in the NSF, an effect that requires adult neurogenesis[12-14]. The NSF test was performed during a 15min period essentially as described[12-14]. The test was conducted by an investigator blind to treatment and genotype groups.

In the splash-grooming test, 200μL of a 10% sucrose solution was squirted on the mouse's snout and the latency to groom was recorded as described[12]. Lower latencies to groom are indicative of lower levels of depression/anxiety in this test. The test was conducted by an investigator blind to treatment and genotype groups.

Changes in coat state were assessed by a blinded scorer of five body parts (head, neck, dorsal/ventral coat, tail and paws). For each area, a score of 0 indicated a well-groomed coat and a score of 1 indicated an unkempt coat[12, 14]. Scores from the five body parts were summed. Lower summed scores are associated with lower anxiety and depressive-like states, whereas higher summed scores are associated with higher anxiety and depressive-like states.

Tissue Processing and Immunohistochemistry

Animals were anaesthetized with isoflurane and perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were post-fixed for 16h and transferred to 30% sucrose. 50μm sections were cut coronally, mounted in consecutive order onto glass slides and coverslipped using a glycerin-based medium. Sections were systematically sampled 480μm apart into 12 wells of a 24 well plate. Free-floating sections were washed, blocked and incubated with primary antibody for DCX (sc-8066, 1:250, SCBT) overnight, washed and stained with biotinylated donkey anti-goat secondary antibody (1:500,Life Technologies) with 10% normal donkey serum. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 30min at room temperature. The horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) reaction was carried out using an avidin/biotin peroxidase complex (VectaStainABC Kit, Vector Laboratories). Sections were incubated in the provided ABC solution for 1h and DAB (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 min. Every 12th section through the hippocampal dentate gyrus was identified and all doublecortin positive cells bodies were counted. Analysis was performed as previously described to count the total number of DCX+ cells and to measure the extent of dendritic branching of DCX+ cells [12].

Study Design

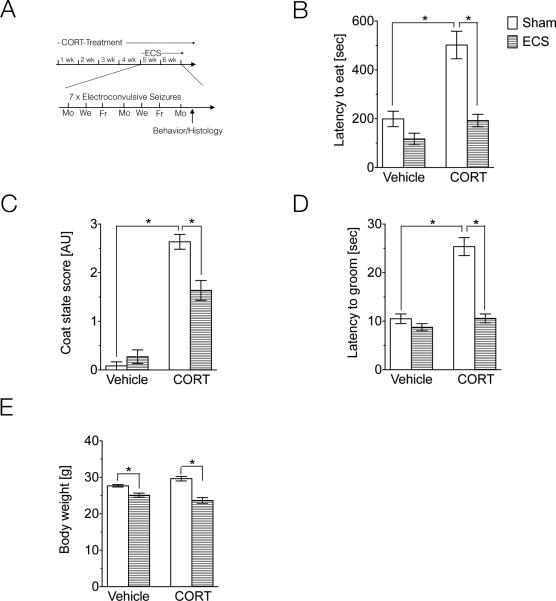

Fig.1A displays a timeline for experiments conducted in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2. In these experiments, CORT or vehicle (β-CD) was administered to 8 week-old, male, wild-type animals in the drinking water for 4 weeks before initiating ECS or Sham treatment. CORT treatment continued throughout the ECS treatment, and was removed from the drinking water after the final ECS session. Behavior experiments or animal perfusion for histology experiments were conducted 48h following the final ECS session. Behavior experiments were conducted on four groups: Vehicle/Sham (n=12), Vehicle/ECS (n=12), CORT/Sham (n=11), CORT/ECS(n=12). One animal was excluded from the Vehicle/Sham group in the NSF test due to an experimental problem. One animal in the Vehicle/ECS and one animal in the CORT/ECS group were excluded due to mild dermatitis making reliable coat scoring difficult. Histology experiments were conducted on a separate cohort of four groups: Vehicle/Sham (n=6), Vehicle/ECS (n=6), CORT/Sham (n=5), CORT/ECS (n=6).

Figure 1.

Electroconvulsive seizures (ECS) rescues behavioral impairments caused by chronic corticosterone (CORT)-treatment, a mouse neuroendocrine model of depression. (A) Schematic depicting the timeline of treatments and procedures for experimental data presented in Figures 1 and 2. (B) Latency to eat in the novelty suppressed feeding test (NSF) in Vehicle and CORT-treated animals that received Sham or ECS treatment. (F) Coat state score in Vehicle and CORT-treated animals that received Sham or ECS treatment. (G) Latency to groom in the splash-grooming test in Vehicle and CORT-treated animals that received Sham or ECS treatment. (H) Body weight in Vehicle and CORT-treated animals that received Sham or ECS treatment.

Figure 2.

ECS robustly increases neurogenesis in vehicle and CORT-treated animals. (A) Representative photomicrographs taken at 10X magnification of migrating neuroblasts labeled with the marker doublecortin (DCX). DCX+ cells are shown in the dentate gyrus of Vehicle/Sham, Vehicle/ECS, CORT/Sham and CORT/ECS and ECS treated animals. (B) Quantification of the total number of DCX+ cells per dentate gyrus in Vehicle/Sham, Vehicle/ECS, CORT/Sham and CORT/ECS animals. (D) Examination of the morphology of DCX+ cells in Vehicle/Sham, Vehicle/ECS, CORT/Sham and CORT/ECS animals. The data shows the number of DCX+ cells containing tertiary dendrites, a measure of dendritic maturation.

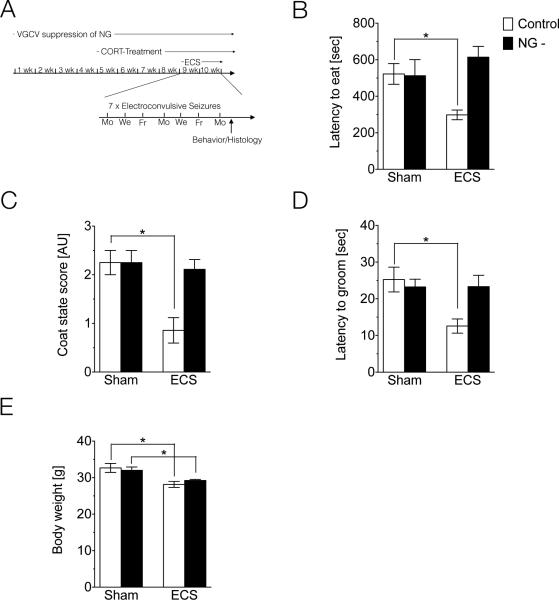

Fig. 3A displays a time line for experiments conducted in Fig. 3. In brief, 8 week-old, male wild-type (Ctrl) and animals without neurogenesis (NG-) began VGCV treatment 4 weeks prior to initiation of CORT administration. VGCV treatment continued for the remainder of the experiment. After 4 weeks of CORT administration, ECS treatment was initiated. CORT treatment continued throughout the ECS treatment, and was removed from the drinking water after the final ECS session. Behavior experiments or animal perfusion for histology experiments were conducted 48 hours following the final ECS session. Behavior and histology experiments were conducted on four CORT-treated groups: Ctrl/Sham (n=9), Ctrl/ECS (n=7), NG-/Sham (n=8), NG-/ECS (n=9). One animal in the NG-/ECS group was excluded due to an experimental problem. All procedures were conducted according to NIH guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Mental Health and/or the Johns Hopkins University.

Figure 3.

Adult-born neurons are required for the behavioral effects of ECS in CORT-treated animals. (A) Schematic depicting timeline of treatments and procedures for experimental data presented in Figure 3. (B) Latency to eat in the NSF test in CORT-treated wild-type (Ctrl) and animals lacking neurogenesis (NG-) that were Sham or ECS treated. (F) Coat state score in CORT-treated Ctrl and NG- animals that were Sham or ECS treated. (G) Latency to groom in the splash test in CORT-treated Ctrl and NG-animals that were Sham or ECS treated. (H) Body weight in CORT-treated Ctrl and NG-animals that were Sham or ECS treated.

Statistical Analysis

Experimental results in the graphical presentations and tabular results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Comparisons of behavior and weight data were analyzed using a 2-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post hoc tests in Prism 6 software (GraphPad). Comparisons of immunohistochemical data were performed using a 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni-Dunn post hoc tests with Statview software. Summary data is presented in graphical format (Fig. 1-3) and raw data and statistical information is presented in Tabular format (Table 1).

Table 1.

ANOVA table for data presented in Fig. 1-3. Mean +/− SEM is presented for each group as well as the p values for the ANOVA. The final four columns present the results of relevant post-hoc analyses.

| Fig. | Vehicle/Sham Mean [SEM] | Vehicle/ECS Mean [SEM] | CORT/Sham Mean [SEM] | CORT/ECS Mean [SEM] | CORT (p) | ECS (p) | Interaction (p) | Vehicle/Sham vs CORT/Sham | Vehicle/ECS vs CORT/ECS | Vehicle/Sham vs Vehicle/ECS | CORT/Sham vs CORT/ECS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1B | 199.3 [31.69] | 117.1 [23.80] | 501.8 [56.36] | 192.6 [25.43] | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0029 | <0.0001 | ns | ns | <0.0001 |

| 1C | 0.08 [0.08] | 0.27 [0.14] | 2.64 [0.15] | 1.64 [0.20] | <0.0001 | 0.0094 | 0.0003 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ns | <0.0001 |

| 1D | 10.5 [1.0] | 8.75 [0.74] | 25.36 [1.84] | 10.58 [0.92] | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ns | ns | <0.0001 |

| 1E | 27.67 [0.33] | 25.08 [0.57] | 29.64 [0.62] | 23.67 [0.77] | ns | <0.0001 | 0.0068 | <0.05 | ns | <0.01 | <0.0001 |

| Vehicle/Sham Mean [SEM] | Vehicle/ECS Mean [SEM] | CORT/Sham Mean [SEM] | CORT/ECS Mean [SEM] | CORT (p) | ECS (p) | Interaction (p) | Vehicle/Sham vs CORT/Sham | Vehicle/ECS vs CORT/ECS | Vehicle/Sham vs Vehicle/ECS | CORT/Sham vs CORT/ECS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2B | 27,668 [3135] | 47,558 [5071] | 18,391 [2014] | 37,740 [2892] | 0.016 | <0.0001 | ns | 0.04 | ns | 0.0075 | 0.0005 |

| 2C | 4476 [905.3] | 9312 [827.8] | 2767 [691.9] | 6856 [600] | 0.0148 | <0.0001 | ns | ns | 0.037 | 0.0028 | 0.0015 |

| Ctrl/Sham Mean [SEM] | Ctrl/ECS Mean [SEM] | NG-/Sham Mean [SEM] | NG-/ECS Mean [SEM] | ECS (p) | NG- (p) | Interacion (p) | Ctrl/Sham vs Ctrl/ECS | NG-/Sham vs NG-/ECS | Ctrl/Sham vs NG-/Sham | Ctrl/ECS vs NG-/ECS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3B | 522.3 [56.46] | 298.3 [26.55] | 512.6 [88.2] | 614.1 [59.11] | ns | 0.0378 | 0.0137 | <0.05 | ns | ns | <0.05 |

| 3C | 2.25 [0.25] | 0.86 [0.26] | 2.25 [0.25] | 2.11 [0.20] | 0.0034 | 0.0141 | 0.0141 | <0.01 | ns | ns | <0.001 |

| 3D | 25.25 [3.37] | 12.57 [1.93] | 23.25 [2.10] | 23.33 [3.10] | 0.032 | ns | 0.03 | <0.05 | ns | ns | <0.05 |

| 3E | 32.66 [1.23] | 28.16 [0.81] | 32.01 [0.91] | 29.22 [0.30] | 0.0002 | ns | ns | <0.01 | <0.05 | ns | ns |

Results

ECS rescues behavior in a neuroendocrine model of depression

In this study we compared the behavioral effects of Sham versus ECS in the neuroendocrine model of CORT-induced depressive-/anxiety-like behavior. As expected, CORT-treatment had a significant effect on latency to feed in the NSF test, suggesting higher depressive-/anxiety-like behavior in the neuroendocrine model of depression. ECS was able to reverse the depressive/anxiety-like state observed in the NSF test after CORT treatment (Fig. 1B, Table 1). We next assessed the coat state of the animals, a well-validated index of a depressed-like state. As expected, CORT treatment led to significantly higher coat state scores, an effect that was reversed by ECS treatment (Fig. 1C, Table 1). We next investigated whether the deterioration of the coat state was linked to changes in grooming behavior by squirting a 10% sucrose solution on the mouse's snout and assessing the latency to groom. CORT treatment had a significant effect on the latency to groom in this test, an effect that was reversed by ECS treatment (Fig. 1D, Table 1). In line with previous studies, CORT treatment slightly increased overall body weight, and ECS led to significant weight decreases in both the vehicle and CORT-treated animals (Fig. 1E, Table 1).

ECS robustly increases measures of neurogenesis

In this study we investigated the effects of ECS in vehicle and CORT-treated animals on measures of hippocampal neurogenesis. ECS significantly increased the total number of migrating neuroblasts (DCX+ cells) in both vehicle and CORT-treated animals (Fig. 2A-B, Table 1). We also assessed the effects of ECS on the dendritic maturation of newly born cells by examining the dendritic morphology of DCX+ cells. ECS significantly increased the number of DCX+ cells containing tertiary dendrites in both vehicle and CORT-treated animals (Fig. 2A,C, Table 1).

New neurons are required for anti-depressive activity of ECS in the neuroendocrine model of depression

In this study, we compared the behavioral effects of ECS in CORT-treated wild-type (Ctrl) animals versus CORT-treated animals lacking neurogenesis (NG-). As expected, ECS significantly decreased the latency to approach in the NSF test in Ctrl animals, suggesting antidepressant activity of ECS. However, the antidepressant effect of ECS was blocked in NG- animals (Fig. 3B, Table 1). Next, we assessed the effect of ECS on coat state in CORT-treated Ctrl animals, and found that ECS significantly improved the condition of the fur. This beneficial effect of ECS was blocked in NG-animals (Fig. 3C, Table 1). Next, we examined the latency to groom in the splash test, and found that ECS significantly decreased the latency to groom in Ctrl animals, indicative of an antidepressant effect of ECS. Again, this effect of ECS was blocked in NG- animals (Fig. 3D, Table 1). As in our previous experiment, a significant decrease in weight was observed after ECS; however, this effect was not affected by loss of neurogenesis (Fig. 3E, Table 1).

Discussion

The mechanisms by which ECT ameliorates depression in humans are not completely understood. ECS enhances adult hippocampal neurogenesis in both rodent and non-human primate models[15-18]. To our knowledge, this report is the first to describe evidence that adult born neurons contribute to the behavioral effects of ECS. Specifically, our data show that the antidepressant-like activity of ECS in a neuroendocrine rodent model of depression requires adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Interestingly, changes in neurogenesis can impact inhibitory control of the hippocampus over the HPA axis[23-25]. While our study design did not allow for meaningful HPA axis measurements due to delivery of exogenous glucocorticoids, future studies should examine whether improvements in neurogenesis induced by ECS can normalize stress-induced HPA axis abnormalities. Such experiments are of interest since they link two hypotheses regarding the mechanisms underlying ECT efficacy, e.g., HPA axis normalization and enhanced neuroplasticity due to increased neurogenesis[20].

Reliable protocols for in vivo measurement of neurogenesis are not yet available in humans, but several promising technologies are under development[11]. Our results suggest that measurements of adult neurogenesis could serve as a potential biomarker to predict and monitor response to ECT in the future. Demonstrating a causal relationship between increased neurogenesis and ECS efficacy is also important pre-clinically. Our findings establish a foundation for future studies aimed at deciphering the cellular mechanisms by which adult born neurons impact hippocampal circuitry to ameliorate depressive-like behavior after ECS treatment. Such experiments are of high importance because understanding the biological mechanisms by which ECT exerts its antidepressant action are crucial to develop improved treatments. Specifically, these findings can be utilized to guide future research designed to improve ECT efficacy and to maximize the length of treatment response. Future studies should examine whether ECS-dependent effects extinguish over time and whether behavioral relapse is associated with changes in levels of adult neurogenesis. Such research is important because relapse is a current limitation of ECT[26].

The therapeutic efficacy of ECT likely depends on a variety of factors that influence neuroplasticity in multiple brain regions. Our data suggest that enhancement of hippocampal neurogenesis may functionally contribute to the antidepressant effects conferred by ECT. Because ECT remains the most effective clinical treatment for both severe and treatment resistant depression, understanding the underlying mechanisms is of paramount importance.

Highlights.

Neurogenesis continues throughout life in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Chronic treatment with monoaminergic antidepressant drugs stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis, and new neurons are required to induce some antidepressant-like behaviors. Electroconvulsive seizures (ECS), a laboratory model of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), robustly stimulate hippocampal neurogenesis, but it is not known whether neurogenesis is required for ECS to exert antidepressant activity. The study utilizes a pharmacogenetic approach to conditionally ablate neurogenesis, and reports evidence that ECS requires new neurons to improve behavior in a rodent neuroendocrine model of depression and anxiety.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided in part by the Intramural Program of the National Institute for Mental Health, the former affiliation of RJS, DVJ, NFH, HKM and KM. Additional funding was provided by the Lieber Institute for Brain Development and the Brain Behavior Research Foundation (NARSAD Young Investigator Awards to RJS, KM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Group UER. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):799–808. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kho KH, et al. A meta-analysis of electroconvulsive therapy efficacy in depression. J ECT. 2003;19(3):139–47. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKay MS, Zakzanis KK. The impact of treatment on HPA axis activity in unipolar major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(3):183–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuuki N, et al. HPA axis normalization, estimated by DEX/CRH test, but less alteration on cerebral glucose metabolism in depressed patients receiving ECT after medication treatment failures. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(4):257–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sapolsky RM. Glucocorticoids and hippocampal atrophy in neuropsychiatric disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(10):925–35. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holsboer F. The corticosteroid receptor hypothesis of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23(5):477–501. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(6):463–75. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bremner JD, et al. Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(1):115–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheline YI, Gado MH, Kraemer HC. Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1516–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christian KM, Song H, Ming GL. Functions and dysfunctions of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2014;37:243–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller BR, Hen R. The current state of the neurogenic theory of depression and anxiety. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;30C:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.David DJ, et al. Neurogenesis-dependent and -independent effects of fluoxetine in an animal model of anxiety/depression. Neuron. 2009;62(4):479–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santarelli L, et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301(5634):805–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Surget A, et al. Drug-dependent requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis in a model of depression and of antidepressant reversal. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(4):293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madsen TM, et al. Increased neurogenesis in a model of electroconvulsive therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(12):1043–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perera TD, et al. Antidepressant-induced neurogenesis in the hippocampus of adult nonhuman primates. J Neurosci. 2007;27(18):4894–901. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0237-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott BW, Wojtowicz JM, Burnham WM. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the rat following electroconvulsive shock seizures. Exp Neurol. 2000;165(2):231–6. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malberg JE, et al. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20(24):9104–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hellsten J, et al. Electroconvulsive seizures increase hippocampal neurogenesis after chronic corticosterone treatment. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16(2):283–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolwig TG, Madsen TM. Electroconvulsive therapy in melancholia: the role of hippocampal neurogenesis. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2007;(433):130–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darcet F, et al. Learning and memory impairments in a neuroendocrine mouse model of anxiety/depression. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:136. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schloesser RJ, et al. Environmental enrichment requires adult neurogenesis to facilitate the recovery from psychosocial stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(12):1152–63. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schloesser RJ, Manji HK, Martinowich K. Suppression of adult neurogenesis leads to an increased hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis response. Neuroreport. 2009;20(6):553–7. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283293e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snyder JS, et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis buffers stress responses and depressive behaviour. Nature. 2011;476(7361):458–61. doi: 10.1038/nature10287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Surget A, et al. Antidepressants recruit new neurons to improve stress response regulation. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(12):1177–88. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kellner CH. Relapse after electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). J ECT. 2013;29(1):1–2. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e31826fef01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]