Abstract

This article presents a pictorial history of the free-ranging colony of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) on Cayo Santiago, Puerto Rico, in commemoration of the 75th anniversary of its establishment by Clarence R. Carpenter in December 1938. It is based on a presentation made by the authors at the symposium, Cayo Santiago: 75 Years of Leadership in Translational Research, held at the 36th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Primatologists in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on 20 June 2013.

Keywords: Cayo Santiago, Santiago Island, macaque, Macaca mulatta, Carpenter

INTRODUCTION

This review presents a pictorial history of the free-ranging colony of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) on Cayo Santiago, Puerto Rico. It is based on a presentation made in commemoration of its 75th anniversary at the symposium, Cayo Santiago: 75 Years of Leadership in Translational Research, held at the 36th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Primatologists (ASP) in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on 20 June 2013.

As far as can be determined, all animals referred to in this review were covered by protocols approved by Columbia University, the University of Puerto Rico (UPR) College of Natural Sciences, the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness (NINDB), and the Caribbean Primate Research Center through the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus; and cared for in accordance with all applicable USDA regulations and USPHS guidelines in effect at the time. The ASP Principles for the Ethical Treatment of Nonhuman Primates have been followed since their inception.

DISCUSSION

The history of the Cayo Santiago (CS) rhesus monkey colony began with the establishment of the “School of Tropical Medicine (STM) of the University of Puerto Rico (UPR) under the auspices of Columbia University” (College of Physicians and Surgeons) in 1926. It was located in a beautiful Neo-Plateresque style building in the Puerta de Tierra section of San Juan (Fig. 1).

The “School of Tropical Medicine of the University of Puerto Rico under the Auspices of Columbia University” in San Juan circa 1938

In 1937, the historic Asian Primate Expedition was conducted by Drs. Harold J. Coolidge Jr., Adolph H. Schultz, Clarence R. Carpenter, Sherwood L. Washburn and others. It was led by Coolidge and funded by the Carnegie Institution, Columbia and Harvard universities, and private donors [Science, 1937]. The expedition brought several gibbons back to Columbia. When George W. Bachman, STM Director, heard about the gibbons, he became interested in using them for his medical experiments. Bachman built outdoor cages for them and subsequently they were shipped to San Juan and housed at the STM (Fig. 2). Carpenter, who was a young psychologist at Columbia's Bard College, transferred to the Department of Anatomy, College of Physicians and Surgeons and was assigned to the STM where he joined Bachman's team (Fig. 3). Other faculty members, namely Drs. Philip Smith and Earle Engle, also wanted primates for research but preferred rhesus monkeys. All four discussed the idea of establishing free-ranging colonies of gibbons and rhesus in Puerto Rico, and Bachman settled on CS as the site [Carpenter, 1959; Rawlins & Kessler, 1986].

Gibbon cages built by Bachman at the School of Tropical Medicine, circa 1937

George W. Bachman (left) and Clarence R. Carpenter (right), circa 1938.

The island was owned by the Pou family of Spain and Puerto Rico which leased it on 1 December 1931 to Antonio A. Roig and his wife, Angelina Oppenheimer, for $60 annually for 15 years with a five-year renewal option. The Roigs of Humacao were sugar cane barons and bankers who used CS primarily for picnics and to graze goats. Figure 4 shows CS as it appeared in the late 1930s with barges arriving at the Punta Santiago pier from the island municipality of Vieques to off load sugar cane and molasses.

Cayo Santiago and Punta Santiago (Roig) pier in background with sugarcane barges from Vieques, circa 1938. Courtesy archives of the Caribbean Primate Research Center (CPRC).

On 9 February 1938, the Roigs assigned their lease to the STM, represented by Bachman, under the same terms. (This corrects previous reports that the Roigs donated CS to the UPR [Rawlins & Kessler, 1986; Kessler, 1989a]). The lease of CS to the STM set the stage for a second expedition in the summer of 1938, this time led by Carpenter and funded by the John and Mary Markle Foundation of Columbia University. He first traveled to the Far East to collect more gibbons and arrived in India in September 1938 to purchase a large number of rhesus monkeys for CS [Carpenter, 1940, 1959, 1972; Rawlins & Kessler, 1986]. Figure 5 shows Carpenter in the field. He had about 500 rhesus captured in 12 districts around Lucknow, a northern part of India east of New Delhi, west of Calcutta (now Kolkata), and just south of the Nepalese border. After tuberculosis testing and crating, Carpenter and the monkeys left Kolkata for the USA on the deck of a Cunard steamship [Carpenter & Krakower, 1941; Carpenter, 1959; Rawlins & Kessler, 1986]. Due to the impending war with Germany, when the ship stopped in Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), the British government informed Cunard that instead of taking the usual shortcut through the Suez Canal, it wanted the ship to do a test run around the southern tip of Africa. Figure 6 is the only photo known to exist of Carpenter on board ship. When Carpenter and the monkeys finally arrived in New York via Boston, they were off loaded onto the SS Coamo for the voyage to Puerto Rico. The Coamo was a famous high speed steam ship that transported passengers from New York to San Juan and Santo Domingo, and vice versa. It was the first ship known to survive and report on going through the eye of a major hurricane, Hurricane San Zenon of 1930, with winds of 150 mph that nearly capsized the vessel [New York Times, 1930]. Figure 7 shows the SS Coamo leaving New York while Figure 8 shows it passing El Morro fort as it enters San Juan harbor.

Carpenter in the field, circa 1938. Courtesy of The Pennsylvania State University (PSU) Archives, Special Collections Library, Clarence R. Carpenter papers.

Carpenter on board deck of a Cunard liner en route from India to New York with rhesus monkeys destined for Cayo Santiago, 1938. Courtesy of Ruth Carpenter.

SS Coamo departing New York. Photograph by Jack Delano courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

SS Coamo passing El Morro Fort as it enters San Juan harbor, circa 1938.

The arrival of the rhesus monkeys in San Juan was heralded in a New York Times article on 22 November 1938 [New York Times, 1938a] that described their 51-day (6 October – 21 November), 14,000 mile journey from India. Carpenter single-handedly cared for the monkeys all the way from Kolkata to San Juan [Carpenter & Krakower, 1941; Carpenter, 1959]. The Times reported on the STM's plans to establish a disease-free breeding colony of free-ranging rhesus on CS to provide animals of known lineage for research on tropical diseases. At that time, as many as 90% of imported rhesus monkeys had tuberculosis [Carpenter, 1972], so there was definitely a need for such a colony. Carpenter had other intentions as well such as providing a resource for studies on the social and sexual behavior of primates in a naturalistic environment [Carpenter, 1972].

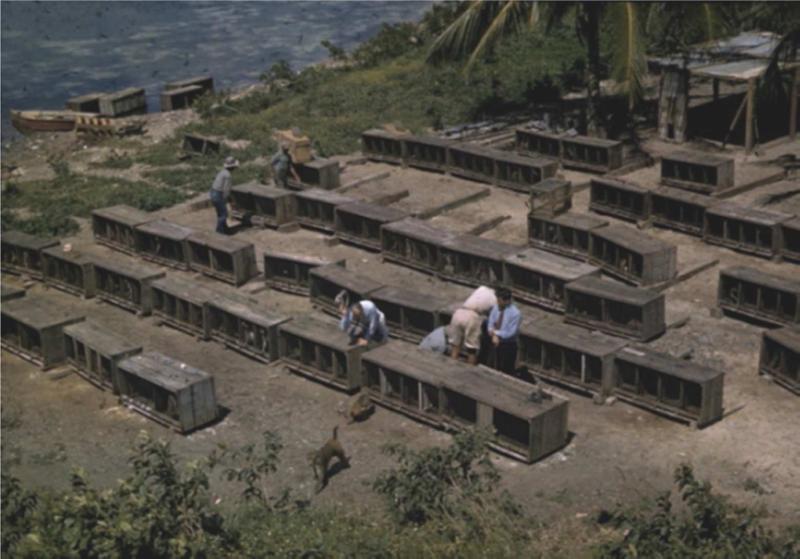

After arriving in San Juan, the monkeys were kept for about two weeks at the STM for tuberculosis testing before they were moved to CS still in their original shipping crates [Carpenter & Krakower, 1941]. Ismael Solis Arroyo began work at CS as a boatman for Michael I. Tomilin, the first colony manager, on 14 November 1938 when he was just 12 years old. Solis met Tomilin at the Roig pier in Punta Santiago and rowed the first dozen four-compartment crates of monkeys out to CS (I. Solis Arroyo, pers. comm., 5 June 2007). According to Carpenter [1972], the first monkeys were released on 2 December. Their release was reported in the New York Times [1938b]. Figure 9 shows the monkeys in their crates on CS. These were also used in January – February 1940 when the monkeys were captured and re-tested for tuberculosis by Tomilin and Luis M. Gonzalez with the aid of Solis ([Carpenter & Krakower, 1941]; I. Solis, pers. comm.). Tuberculosis, dysentery and fighting were the main causes of mortality in the colony during the first two years [Carpenter & Krakower, 1941].

Original monkey shipping and holding crates on Cayo Santiago. Courtesy of The Pennsylvania State University Archives, Special Collections Library, Clarence R. Carpenter papers (PSUA 149).

Figure 10 shows part of the Punta Santiago pier as it appeared in 1938. In the photo, notice a small building, a narrow-gauge railroad car and the beach. Access to CS in those years was exclusively by rowboat from dockside or the beach. Figure 11 shows Carpenter in the rear of a rowboat with Mr. and Mrs. Tomilin and some unidentified animal caregivers. The pier, which has been renovated several times over the decades due to storm damage, has been used almost exclusively since the early 1980s to access CS.

The Roig or Punta Santiago pier on “mainland” Puerto Rico, circa 1938, used to access Cayo Santiago by boat. Courtesy of The Pennsylvania State University Archives, Special Collections Library, Clarence R. Carpenter papers (PSUA 149).

Carpenter (in stern) behind Michael and Eugenie Tomilin being rowed out to Cayo Santiago, circa 1938. Courtesy archives of the Caribbean Primate Research Center.

LIFE Magazine dispatched one of its chief photographers, Hansel Mieth, to CS to document the release of the monkeys between 2 December 1938 and 2 January 1939 [Carpenter, 1972]. LIFE published two articles on the establishment of the colony. The first (Fig. 12) appeared in the 2 January 1939 issue. This article mentioned that Mahatma Gandhi was already preaching against the exportation India's sacred rhesus monkeys for research, but it was not until 37 years later, in 1976, that an export ban was actually imposed. The article gave the price of rhesus monkeys as $8 to $25 each compared to thousands of dollars today. Unfortunately, this article contained some misinformation leading to rumors in Punta Santiago that the monkeys were carrying human diseases such as polio and leprosy. School and government officials subsequently held a town meeting to dispel these rumors and to inform everyone that the purpose of the colony was to produce healthy monkeys. Bachman also wrote the science editor of LIFE about the inaccuracies contained in their article [Rawlins & Kessler, 1986].

LIFE Magazine article on establishment of the Cayo Santiago colony with photographs by Hansel Mieth, 2 January 1939. Courtesy of Time & Life Pictures.

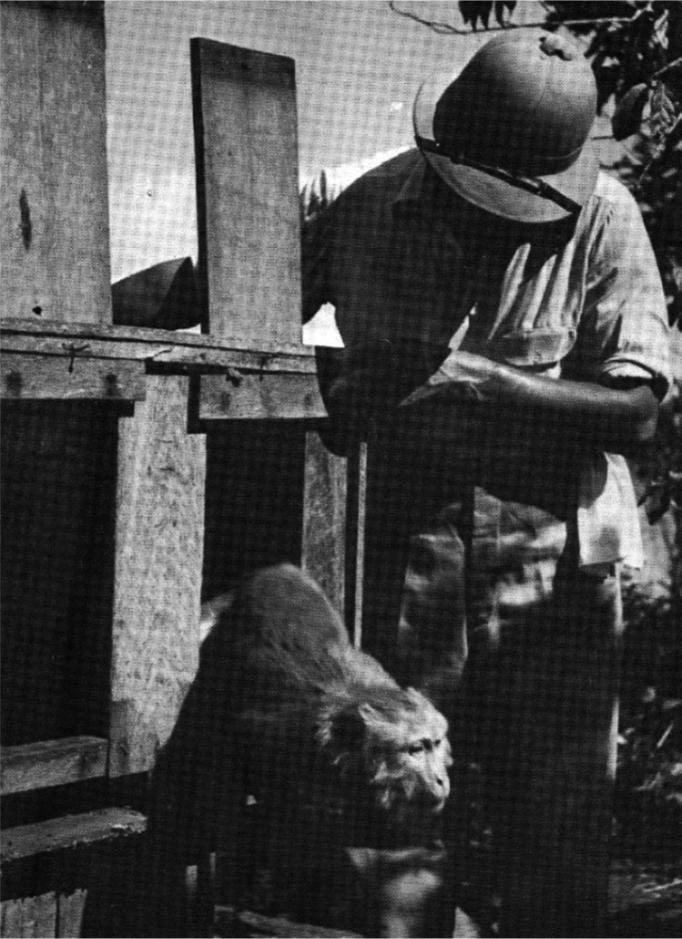

Figure 13 shows Tomilin tattooing monkeys. They were tattooed and ear notched for identification before their release. Also shown are members of the animal care staff including two local teenagers, including Solis, who volunteered to work on the island.

Tomilin tattooing monkeys prior to their release onto Cayo Santiago assisted by members of the staff including Ismael Solis hidden behind Tomilin. Photograph by Hansel Mieth courtesy of Time & Life Pictures.

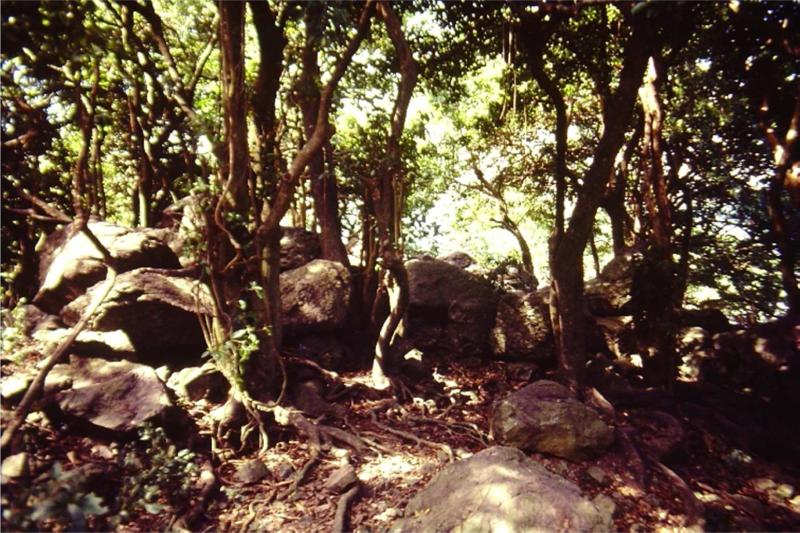

Figure 14 shows Mieth's photograph supposedly of the first monkey being released onto CS. Figure 15 shows a young Solis releasing another member of the 409 founders that included 40 adult males and 183 adult females [Carpenter, 1972]. Figures 16 and 17 taken in 1939 and 2009 from the same location show members of the founding stock and the forestation that took place over the years, respectively.

Release of the first rhesus monkey on to Cayo Santiago, 2 December 1938. Photograph by Hansel Mieth courtesy of Time & Life Pictures.

Ismael Solis releasing a monkey on to Cayo Santiago, December 1938. Photograph by Hansel Mieth courtesy of Time & Life Pictures.

Members of the founding stock of rhesus monkeys on Cayo Santiago, 1939. Courtesy archives of the Caribbean Primate Research Center.

Photograph of same location as Figure 16 taken in 2009 showing dense forestration that took place on Cayo Santiago over the years.

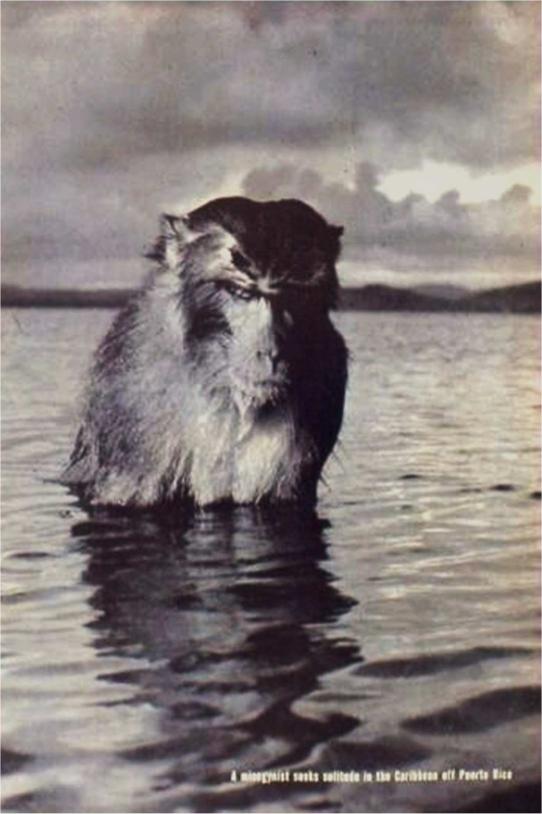

LIFE Magazine of 16 January 1939 contained one of its most famous photographs, that of a solitary adult male rhesus standing in the water between CS and mainland Puerto Rico. The photograph (Fig. 18) was entitled “the Misogynist” by the editor. In the Public Broadcasting Service television documentary, “Hansel Mieth: The Vagabond Photographer”, produced by Nancy Schiersari (http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/hanselmieth/), Mieth discusses how she waded far out into the water with her camera to get this historic photograph. The distance she traveled into this shark-infested bay is evident from an unpublished photograph discovered by the authors in The Pennsylvania State University Carpenter archives (Fig. 19). The LIFE photo was so popular that it was republished in several other issues (25 November 1946, 26 June 1950, 26 February 1951 and 26 December 1960), sometimes with other captions. When the magazine cover featured an impressive color photograph of a bathing Japanese macaque by Co Rentmeester on 30 January 1970, many readers wrote to LIFE recounting their memories and emotions about Mieth's “Misogynist” [Flamiano, 2005].

Famous “Misogynist” photograph by Hansel Mieth that appeared in the 16 January 1939 issue of LIFE Magazine. Photograph courtesy of Time & Life Pictures.

Distant photograph of the male “misogynist” rhesus monkey in the waters of Cayo Santiago as photographed by Hansel Mieth in 1938 and discovered in the PSU archives by Kessler. Courtesy of Time & Life Pictures.

Mieth went on from CS to pursue an important and dangerous photographic career with her photographer husband, Otto Hagel. They covered socially significant events in the USA, such as the great Longshoremen's strike on the West Coast, one of the first violent labor altercations in the country. She also documented Japanese internment camps during WWII, especially Heart Mountain in Montana. LIFE Magazine never published these stories, apparently for political reasons. Mieth and her husband also refused to cooperate with the infamous McCarthy investigation of un-American activities and, as a result, they lost their jobs with LIFE and had to return to their farm in California. In the “Vagabond Photographer”, Mieth emphasizes the significant psychological impact her brief encounter with the Misogynist and the other monkeys on CS had on her entire life and career. It remains her most enduring photograph and is discussed in detail by Flamiano [2005].

In the early days of colony there was minimal provisioning. Papaya trees planted on the island were quickly destroyed by the monkeys and the coconut trees had yet to reach maturity. Local vegetables, including corn, and fruits were brought out to the island and fed to the monkeys by the staff (Fig. 20). The monkeys were later fed Purina Fox Chow and then Monkey Chow as well as other commercial primate diets once companies began producing them in the States. Figure 21 shows Tomilin, attired in shorts, hand feeding monkeys corn so that he could census them. Back then, and for many years afterward, personal protective equipment (PPE) was not required.

An animal caregiver is seen here bringing local fruits and vegetables on to Cayo Santiago to feed the monkeys. Photograph by Hansel Mieth courtesy of Time & Life Pictures.

Tomilin feeding Cayo Santiago monkeys corn kernels in order to census them. Photograph by Hansel Mieth courtesy of Time & Life Pictures.

In April 1939, Carpenter released 14 gibbons (Hylobates lar) onto CS (Fig. 22) [Carpenter, 1972]. The co-habitation of CS by gibbons and rhesus monkeys was not successful for at least two reasons: (1) the gibbons attacked human observers, and (2) the first gibbon infant born on the island was killed by the rhesus. The gibbons were recaptured and put into protective pens (Fig. 23) until the spring of 1941 when they were moved to the STM in San Juan. Ultimately, they were relocated to stateside zoos [Carpenter, 1972].

One of the 14 gibbons released on to Cayo Santiago by Carpenter in April 1939. Photograph by Carpenter courtesy of The Pennsylvania State University (PSU) Archives, Special Collections Library, Clarence R. Carpenter papers.

The Cayo Santiago gibbons confined to a protective pen, circa 1939. Photograph by Carpenter courtesy of The Pennsylvania State University (PSU) Archives, Special Collections Library, Clarence R. Carpenter papers.

Tomlin accompanied by his wife, Eugenie, was the first of two resident caretakers for the colony. They lived in a wooden house on the Big Cay hill from 1938 to 1947 (Fig. 24). Rainwater was collected for drinking, cooking and the toilet. The remnants of the house, its concrete basement, later became a field research lab that was used to examine and test monkeys during the annual roundup of the colony until 2001 when it was replaced by a modular veterinary clinic. The Tomlin's had a favorite rock to the west of the house on which they would sit with their pet rhesus monkey, “Pijita” (“Little Thief”, Fig. 25). Despite being a rascal of a monkey, who raided the Tomilin's kitchen, Mrs. Tomlin used to take Pijita to Punta Santiago on a leash and let her interact with the local populace (I. Solis, pers. comm.). The area around the rock is now heavily wooded, but back then it was almost totally devoid of vegetation as can be appreciated by comparing Figure 25 with 26 from 1939 and 2013, respectively.

The Tomilin house on the Big Cay hill of Cayo Santiago, circa 1939. Courtesy archives of the Caribbean Primate Research Center.

Michael and Eugenie with their pet rhesus monkey “Pijita” at their favorite rock adjacent to their house on Cayo Santiago, circa 1939. Punta Santiago can be seen in the background. Courtesy archives of the Caribbean Primate Research Center.

The “Tomilin rock” landmark on Cayo Santiago as of 2013.

Tomilin was a legendary figure in Puerto Rico and many stories about this Russian émigré abound. Before coming to CS, Tomlin worked at the Philadelphia Zoo and with the original Yerkes chimp colony in Orange Park, Florida. Yerkes personally recommended him to Carpenter for the CS job. Quite a giant of a man, Tomilin was said to regularly swim across the one kilometer channel between CS and Punta Santiago, drink a fifth of vodka and then swim back to his wife and the monkeys. Although Tomilin actually did make this roundtrip swim, he reportedly preferred rum and Coke® and did not like vodka despite being Russian (I. Solis, pers. comm.). In 1986, William J. Dorvillier, a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, wrote a memorable commentary about Tomilin in The San Juan Star newspaper entitled “The Monkey Man” [Dorvillier, 1986].

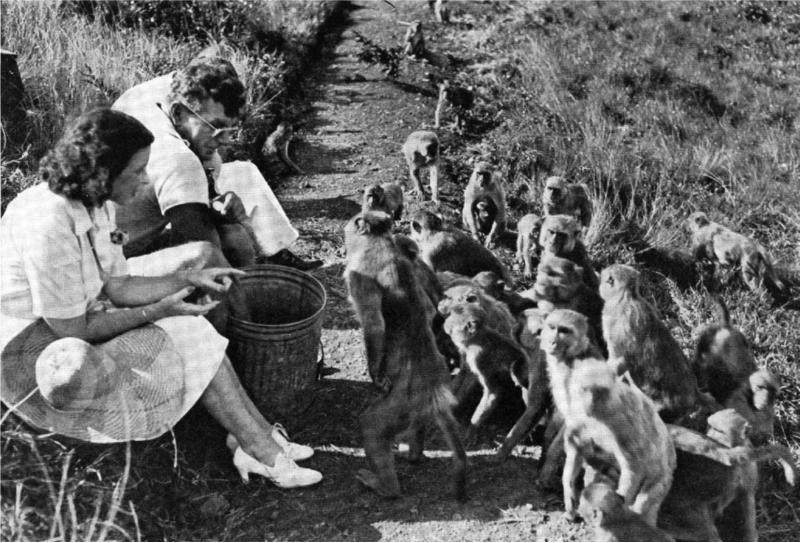

Carpenter's research on CS during the late 1930's and early 1940's concentrated on the social and sexual behavior of rhesus monkeys. Figure 27 shows him and his first wife, Mariana Evans, arriving at the Humacao airport. He reportedly always carried a still or movie camera (J. Baulu, pers. comm.). Figure 28 from the December 1939 National Geographic Magazine shows the Carpenters on CS hand feeding the monkeys.

Carpenter and his first wife, Mariana, arriving at Humacao Airport, circa 1939. Note the movie camera in Carpenter's hand. Courtesy archives of the Caribbean Primate Research Center.

Photograph of the Carpenters feeding monkeys on Cayo Santiago that appeared in the December 1939 issue of National Geographic Magazine. Courtesy of the National Geographic Society.

Other studies on CS at the time focused on shigellosis and “strep throat.” James Watt, who later became Director of the NIH National Heart Institute, moved his lab from Bethesda to San Juan in order to study the shigellosis epizootic that caused enteritis, abortions and the deaths of about 26 pregnant monkeys [Carpenter, 1940]. In Figure 29, researchers studying strep throat can be seen probing the mouth of a CS rhesus without the use of any PPE. This was before knowledge about, and precautions against, B virus (herpes B, Herpesvirus simiae, Cercopithecine herpesvirus I, Macacine herpesvirus I) became widespread.

Early researchers studying strep throat probe the mouth of a rhesus monkey. Note the lack of any personal protective equipment such as masks, gloves and eye protection. Courtesy archives of the Caribbean Primate Research Center.

With the onset of World War II, the SS Coamo was converted into a US Merchant Marine troop carrier (Fig. 30). It was ideal for this mission because it could outrun most German submarines. In the book “No Ordinary War: The Eventful Career of U-604” [Prag, 2009], there is a detailed description of the sinking of the Coamo on 2 December 1942 by this notorious submarine. Several men survived but they were left stranded on their rafts by U-604 (Fig. 31) and eventually they all perished at sea. The sinking of the Coamo resulted in the largest Merchant Marine loss of the war [Prag, 2009].

The SS Coamo is seen here after its conversion into the US Merchant Marine USAT Coamo for World War II.

German submarine (U-boat), U-604, and crew that sank the SS Coamo (USAT Coamo) on 2 December 1942. Photograph courtesy of U-604's radioman, Funkmaat Georg Seitz, through Peter Binnefeld and Christian Prag.

Between 1 July 1943 and 20 June 1944, two things happened with the colony: (1) 100 rhesus were shipped to the states through “submarine-infested waters” for war-related studies [Morales Otero, 1944]. (About 200 rhesus in total were eventually shipped from CS to the states for this purpose [Frontera, 1958; Carpenter, 1972]), and (2) it was transferred from Columbia University to the UPR College of Natural Sciences. This was a time of nightly blackouts and submarine lookouts in Puerto Rico. Today one can visit remnants of a lookout station along the eastern shore of Puerto Rico overlooking CS, Humacao beach and the Vieques Channel. More tonnage was sunk in the Caribbean by German U-boats than in the Atlantic because of the focus on eliminating the Allies’ essential Venezuelan oil supply. This oil was also critical to Puerto Rico because all of its electricity was generated from fuel oil. Despite the danger and lack of funds, locals continued to bring vegetables and fruits out to CS to feed the monkeys.

By 1947 UPR could no longer support the monkeys and on 11 July 1947 it offered the colony to any institution through an advertisement in the journal Science. Tomilin and his wife left CS and were replaced by Rafael Luis Nieva, the only other colony manager in the history of the colony to live on the island with the monkeys [Frontera, 1989].

At this critical juncture, Jose Guillermo Frontera, a doctoral candidate from Puerto Rico studying neuroanatomy at the University of Michigan, wrote the UPR Department of Biology Chair, Ana Diaz-Collazo, (not Dean Facundo Bueso as previously reported) on 19 December 1947 to convince her that the colony was too valuable to give away. She subsequently convinced the Dean to support the colony until Frontera could finish his PhD and return to Puerto Rico. During the summer of 1948, Frontera returned to UPR and met with the Dean about the state of the colony. He found out that Bueso had already hired Nieva to replace Tomilin and was supporting the monkeys. In addition, he had invited a group from NIH to visit CS that September. As a consequence, Frontera was awarded a two-year grant from the NINDB to support the colony ($15,000 annually; about $145,000 in 2014 dollars) and his neuroanatomical research ($4,000 annually; about $39,000 in 2014 dollars) [Frontera, 1989]. This was the first of two times that Frontera saved the CS colony although he gave credit for this to Dean Bueso [Frontera, 1989]. Figure 32 is a famous cartoon by Carmelo Filardi published on 8 December 1949 in Puerto Rico's largest newspaper at the time, El Mundo, about this historic grant award, the first NIH grant for Puerto Rico and UPR. Note that the entire NIH budget at the time was only $8 million.

“En las Papas” (to be well off financially), a cartoon by Carmelo Filardi published on 8 December 1949 in El Mundo newspaper announcing Jose Guillermo Frontera's NIH grant to support the Cayo Santiago colony. Courtesy of Jose Guillermo Frontera and family.

On 15 May 1949, Governor Luis Muñoz Marin signed into law a bill from the legislature of Puerto Rico creating the UPR School of Medicine [Ramirez de Arellano, 1985] into which was merged the STM, and on 24 October 1949 CS was expropriated from the Pou and Roig families by Puerto Rico for the new school at the fair price of $3000. The next year, Frontera moved from the Department of Biology at the College of Natural Sciences to the Department of Anatomy at the School of Medicine which remained located in the STM buildings until it moved to the new Medical Center in Rio Piedras in the mid-1960s. On 7 February 1951, CS was officially transferred from the central government to the UPR School of Medicine. Later the same year, CS was visited by the Chief of NIH's Research Grants and Fellowships Program accompanied by UPR officials and Frontera. As a result, his grant to support the CS colony was extended for two years and in 1954 he was awarded another NIH research grant to work in New York at Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons.

In May 1955, Frontera travelled to Bethesda to meet with William F. Windle, Chief of the NINDB Laboratory of Neuroanatomical Sciences, about his research and the need for long-term support of the CS colony. This was the second time that Frontera intervened to save the colony. Shortly thereafter, Windle notified Frontera, who had returned to Puerto Rico by then, that he would soon be lecturing on asphyxia neonatorum at the Veterans Administration Hospital in San Juan. At the lecture, Windle introduced Frontera to his former graduate students and close friends, Drs. Max and Maria Ramirez de Arellano, neurosurgeon and neurologist, respectively. They had excellent contacts on the island and negotiations between UPR and NIH officials, including Pearce Bailey, NINDB Director, for the establishment of a collaborative research laboratory in San Juan commenced almost immediately. Negotiations, however, were breaking down but were eventually resolved at a meeting between UPR and NIH officials with Governor Luis Muñoz Marin. A few months later, in September 1956, the historic “Conference on Asphyxia Neonatorum, Brain Damage and Impairment of Learning” was held at the UPR School of Medicine under its and NINDB's auspices, and sponsored by United Cerebral Palsy, the Association for the Aid of Crippled Children, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and NSF. This was the inaugural event for the new NINDB Laboratory of Perinatal Physiology in San Juan (LPP, Fig. 33), the proceedings of which were published in 1958 [Windle et al., 1958; Windle, 1980; Rawlins & Kessler, 1986; Frontera, 1989]. The primary mission of the LPP was to find a cure for cerebral palsy and its sequela, mental retardation. At the time, United Cerebral Palsy estimated that there were about 500,000 cerebral palsied individuals in the USA and that about 16,000 new cases were occurring each year [Windle et al., 1958]. Windle oversaw the LPP from Bethesda and Ronald E. Myers served as its director. Maria Ramirez de Arellano served as Interim Director and Director for a time. There were many scientists at, or associated with, the LPP and it was quite an active research lab with an international reputation. The LPP had collaborations with investigators from institutions around the world, including the Sukhumi Primate Center (Russian Primate Research Center or Russian Institute of Medical Primatology), once the oldest and largest primate center in the world [Fridman & Bowden, 2009; Johnsen et al., 2012].

Cover of brochure for the NINDB Laboratory of Perinatal Physiology in San Juan established in 1956 and closed on 30 June 1970.

Cayo Santiago became the Behavioral Ecology Section of the LPP. It not only supplied the animals needed for research at the LPP but also provided resources for behavioral and reproductive studies under naturalistic conditions [Frontera, 1958]. Cayo Santiago benefited from the establishment of the LPP in at least three ways. The first was in research infrastructure. Figure 34 shows the new laboratory facility that was built in Punta Santiago. It no longer exists, but at the time it was state-of-the-art. Another was in personnel, namely Stuart Altmann, Edward O. Wilson's first doctoral student at Harvard University, who arrived on CS in June 1956 (Fig. 35). Almost immediately, he caught and remarked the monkeys (Fig. 36), and began a daily census of the colony that continues today. Altmann not only studied the sociobiology of rhesus, but also their physical growth, development and dentition. Figure 37 shows him working with Frontera. In 1962, Altmann published his classic study of the CS monkeys, based on his dissertation research, and coined the term “sociobiology” [Altmann, 1962] which has since entered the annals of science through its adoption by his mentor, Wilson. The third was a steady supply of commercial monkey diet, initially Purina Monkey Chow from St. Louis (Fig. 38).

The Laboratory of Perinatal Physiology's beach front laboratory and office building in Punta Santiago. Photograph by Richard Rawlins.

Photograph of Stuart Altmann arriving on Cayo Santiago in June, 1956. Courtesy of Jose Guillermo Frontera and family.

Altmann tattooing a rhesus monkey on Cayo Santiago in 1956. Photograph courtesy of Jose Guillermo Frontera and family.

Altmann (left) and Frontera (right) collecting anthropometric data on a Cayo Santiago rhesus macaque. Photograph courtesy of Jose Guillermo Frontera and family.

Animal caregivers dispensing Purina Monkey Chow directly to monkeys on Cayo Santiago prior to the construction of feeding corrals. Courtesy archives of Caribbean Primate Research Center.

In May 1960, Watt announced that the “nation's second (NIH-funded) monkey colony for long-range studies of chronic diseases” would be opened at the University of Oregon, the first being CS funded by NINDB [New York Times, 1960]. Another $2 million was set aside to start what became the Regional Primate Research Center's (RPRC) Program [Windle, 1980; Frontera, 1989; Rawlins & Kessler, 1986; Dukelow, 1995].

Carl B. Koford (Fig. 39), best known for his field work on the California condor, succeeded Altmann as CS Scientist-in-Charge in 1958. In 1960, he visited Boris Lapin and Lelita Yakovleva at Sukhumi. As a result, their book on the comparative pathology of monkeys was translated into English and published in 1963 as collaboration between the NINDB and the USSR's Institute of Experimental Pathology and Therapy, Academy of Medical Sciences in Sukhumi [Lapin & Yakoleva, 1963].

Carl Koford (left) and others on Cayo Santiago, circa 1960. Courtesy archives of the Caribbean Primate Research Center.

About this time, another young biologist, Charles H. Southwick became involved with the CS colony. He had worked with Carpenter in Panama on Barro Colorado Island and was studying the behavior, reproduction and demography of feral rhesus in urban and rural India. In 1963, Southwick (Fig. 40) edited a seminal little paperback book, “Primate Social Behavior” [Southwick, 1963], containing chapters by the world's leading primatologists of the day such as Carpenter and Koford. It became the most widely used college text for the budding field of primatology. Southwick has remained directly or indirectly involved with the CS colony for more than 50 years [Southwick, 2015, this issue].

Charles Southwick in 2009 displaying his seminal little 1963 paperback “Primate Social Behavior.” This edited volume was the leading primatology textbook of its time and is now a classic. Photograph by Kessler.

Windle, who had moved to San Juan to oversee the LPP, resigned from his faculty appointment with the UPR School of Medicine in 1963 and affiliations between the LPP and UPR began to deteriorate despite attempts to restore relations [Windle, 1980].

In 1964, Carpenter published “Naturalistic Behavior of Nonhuman Primates”, a compilation of all his major papers from 1934 through 1962 [Carpenter, 1964]. The book included his work with New World monkeys, apes and macaques in Panama, the Far East and at CS, respectively.

While Koford was head of the Behavioral Ecology Section, the LPP tripled the number of island colonies of rhesus monkeys in Puerto Rico. Figure 41 shows the two islands off the southwestern coast of Puerto Rico (La Cueva and El Guayacan) that comprised the LPP's La Parguera Primate Facility. These “islands” were more like peninsulas as they were essentially connected to the mainland by mangrove bridges. NIH put the first monkeys there from CS in the 1960s and then Koford traveled to India and obtained more for this facility, including two “golden” rhesus macaques [Kessler et al., 1986]. In the mid-1970s, the Food and Drug Administration added many more free-ranging rhesus to breed them for their poliovirus vaccine testing program [Kerber et al., 1979]. Patas monkeys (Erythrocebus patas) were also introduced and housed in corrals or released to be free-ranging on El Guayacan. Some monkeys from both colonies escaped from the facility to the Sierra Bermejas mountain chain seen in the background of Figure 41 and the surrounding area of Lajas where they became agricultural pests. The ecological consequences of these escapes were investigated by Janis Gonzalez-Martinez who did her doctoral dissertation research on the escaped patas and rhesus with Southwick at the University of Colorado at Boulder [Gonzalez, 1998, 2004].

Aerial photograph of El Guayacan (left) and La Cueva (right) islands of the LPP's and CPRC's La Parguera Primate Facility. Note the Sierra Bermeja mountain chain in the background. Courtesy archives of the Caribbean Primate Research Center.

In July 1966, an experiment to test the ability of the CS rhesus monkeys to adapt to a non-provisioned island, with no source of drinking water except rainfall, was undertaken by the LPP on Desecheo Island, 21 kilometers off the west coast of Puerto Rico (Fig. 42). The rhesus transferred from CS to Desecheo adapted quite well and Morrison and Menzel published a famous wildlife monograph on the experiment [Morrison & Menzel, 1972]. Several attempts have been made since the late 1970s to remove this introduced rhesus population because of purported damage to the migrant brown and red-footed boobie bird nesting populations. These populations declined drastically after the monkeys were put on the island [Evans, 1989]. However, a press release on 1 May 2012 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service suggested that black rats, not monkeys, were responsible for the decimation of what was once the world's largest brown boobie bird nesting population (see http://www.fws.gov/caribbean/refuges/desecheo/restoringdesecheo.pdf).

In the 1960s, Desecheo Island, off the west coast of Puerto Rico in the Mona Passage, was the site of a unique NIH-sponsored experiment in the adaption of Cayo Santiago-derived rhesus monkeys to an arid tropical environment. Photograph from the NINDB Laboratory of Perinatal Physiology (LPP) in San Juan brochure.

When Koford left the LPP in August 1966, responsibilities for overseeing CS were subsequently shared by Elizabeth A. Missakian, Marge A. Varley, Halsey M. Marsden, Steven H. Vessey, John A. Morrison, John H. Kaufmann and Andrew P. Wilson who were conducting a variety of behavioral studies with the colony.

In the 1960s, the LPP was also in the process of establishing large outdoor corralled groups of rhesus at its Sabana Seca Field Station (SSFS), just west of San Juan, for other mission-oriented experiments and behavioral studies. These were located in a cleared area within a subtropical forest on federal property behind a US Navy communications base (Fig. 43). The arrows in Figure 44 indicate the extent to which the LPP had expanded from San Juan and CS to other parts of Puerto Rico including the SSFS, the islands adjacent to La Parguera and Desecheo Island. Due to the success of the research at the LPP in San Juan using monkeys from CS, Congress appropriated, and NIH assigned, funds to replace the old LPP with a new laboratory on the grounds of the UPR Medical Sciences Campus (MSC) (Fig. 45). However, funding for the LPP's other island colonies was cut by NINDB and the political dispute that arose between UPR and NINDB in the mid-1960s continued despite attempts at reconciliation [Windle, 1980]. Figure 46 shows a section of a chapter frontispiece by Joel Ito [Dukelow, 1995] attempting to depict the complexities of the relationship among the UPR, NIH (LPP) and Congress. The conflict eventually led to the decision by NINDB to close the LPP. Ironically, in 1969 Carpenter was brought back to head a study group to resolve the conflict. His committee produced a report [Carpenter, 1969] with recommendations that ultimately led to establishment of the CPRC on 1 July 1970 (Fig. 47) under a NIH Animal Resources Branch contract overseen by William J. Goodwin. The actual name of the new center, as a de facto regional center, came from Carlos Torres Colondres, the LPP administrator. When the LPP closed, Torres, an attorney and accountant, chose to remain in Puerto Rico and become the CPRC Administrator, a position he held until his retirement from UPR in 1992.

Photograph of the original site for the CPRC's Sabana Seca Field Station, circa 1965, on which the LPP later was starting to build large outdoor corrals. Courtesy archives of the Caribbean Primate Research Center.

A map of Puerto Rico indicating all of the primate facilities under the domain of the LPP in the late 1960s (LPP in San Juan, Cayo Santiago, La Parguera Primate Facility, Desecheo Island and Sabana Seca Field Station).

Aerial photograph of the new Puerto Rico Medical Center “Centro Medico” on which was located the UPR Medical Sciences Campus. The new NINDB LPP was supposed to be located on this site.

Part of a frontispiece by Joel Ito from W. Richard Dukelow's book, “The Alpha Males: An Early History of the Regional Primate Research Centers” attempting to depict the political complexities among NIH, UPR and Congress. Courtesy of Joel Ito and W.R. Dukelow.

English and Spanish language brochures for the Caribbean Primate Research Center.

Clinton Conaway, a zoologist from the University of Missouri, was appointed the CPRC's first director. He recruited Donald S. Sade of Northwestern University (NU) to serve as CS Scientist-in-Charge and William T. Kerber as CPRC veterinarian. Sade began work in July of 1970 and had a number of NU students collecting data and doing graduate research on the demographics and social behavior of the monkeys. His “Basic Demographic Observations on Free-Ranging Rhesus Monkeys” [Sade et al., 1985] funded by a large NSF grant contains information on colony history, its management and population demography, accompanied by appendices containing matrilines and notes from the early days of the colony. Koford hired, and Sade retained, the services of Angel “Guelo” Figueroa, as chief census taker from 1973 – 1983 and mentored future Scientist-in-Charge, Richard G. Rawlins. After removal of all animals and groups that had been manipulated under the LPP, Sade instituted a period of nonintervention of the colony in 1973 that was maintained under Rawlins and Kessler from 1975 until the major cull of the population in 1984 (see below).

Figure 48 shows Figueroa at one of the trapping/feeding corrals and a “blind” where census takers hide in order to catch monkeys during the annual roundup. Once caught, they are sedated and yearlings are tattooed and ear notched. In recent years, yearlings and other animals have been given physical examinations, provided biological samples for studies, and bled for paternity testing and maternity confirmation using genetic analyses [see Widdig et al., 2015, this issue].

Angel “Guelo” Figueroa, Cayo Santiago's Chief Census Taker from 1973 - 1983, shown capturing monkeys during an annual winter roundup. Photograph by Rawlins.

Sade also started the CPRC Skeletal Collection in the early 1970's by macerating the carcasses of monkeys dying on CS. Rawlins continued to collect and curate deceased animals from 1975 through 1981. In the early 1980s, Drs. Jean E. Turnquist and Matthew J. Kessler started the routine collection of carcasses from all species maintained at the SSFS. Edgar Davila, who was a CS census taker, periodically macerating carcasses at CS and SSFS (Fig. 49). In 1982 the CPRC Museum was established at the School of Medicine to house all of the skeletons stored in Punta Santiago and SSFS. Dean Falk was appointed Curator, and in 1984 she obtained a NSF grant to help curate the CS skeletons. Turnquist succeeded Falk as Curator in 1986 and remained in that position for 17 years. John G.H. Cant and Donald C. Dunbar succeeded her. The curators were assisted by dentist and medical illustrator, Nancy Hong, and then Terry B. Kensler, who currently serves as de facto curator. In 2011, forensic anthropologist, television producer of “Bones” and novelist, Kathy J. Reichs, who did some collaborative research with the skeletons in the early 1990s, lent her support to the collection by allowing the CPRC to use her image and linking the CPRC Skeletal Collection to her website (http://kathyreichs.com/about-kathy/getting-involved/cprc/) in an effort to promote more studies with the bones (Fig 50). The collection now consists of over 3,600 complete boxed rhesus skeletons, including 3,000 from CS rhesus (Fig. 51) [Dunbar, 2012; Wang, 2012, 2015, this issue; Widdig et al., 2015, this issue].

Edgar Davila, Cayo Santiago Chief Census Taker (1984 - present), preparing skeletons for the CPRC Skeletal Collection.

2011 promotional announcement and web links for the CPRC Skeletal Collection (aka Laboratory of Primate Morphology and Genetics) featuring Kathy Reichs. Courtesy of Kathy Reichs.

Typical boxed disarticulated complete skeleton of a Cayo Santiago rhesus macaque curated at the CPRC Skeletal Collection. Note that all bones are labeled with tattoo and accession numbers.

In 1975, Kerber took over as CPRC Director and continued to serve as veterinarian, and Rawlins was appointed CS Scientist-in-Charge upon Sade's return to NU in 1976 (Fig. 52). Rawlins’ career with primates began on CS in 1971 as a graduate student and he served as Scientist-in-Charge from 1976-1981. He remained associated with the CPRC through 2013 as a member, and then chair, of the Chancellor's External Advisory Committee on the CPRC (CPRC EAC) through which he provided valuable advice on the operation of CS to many Chancellors and Presidents of UPR.

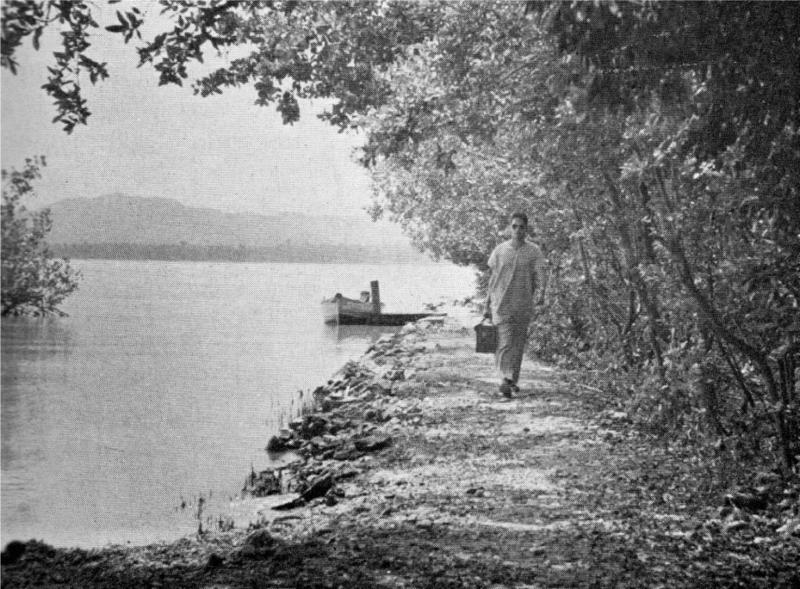

Former CPRC Director William T. Kerber, Richard Rawlins, Cayo Santiago Scientist-in-Charge, and boatman, Hector Vazquez, boating back from the island, February 1977. Photograph by Kessler.

In 1977, Kessler was recruited as the new veterinarian (Fig. 53) and given the title Director of Veterinary Activities. Rawlins’ research interests focused on locomotion and population biology. Both he and Kessler became increasingly concerned about the impact of tetanus on the animals as individuals and on the population as a whole. Their mutual interest in studying tetanus resulted in their first article on the CS macaques [Rawlins & Kessler, 1982], and the realization that behavioral biologists and clinical veterinarians could work cooperatively with the colony under the management policy in effect at the time. This understanding led to a new period at CS during which the colony was effectively used for noninvasive biomedical research during the annual winter round without disrupting ongoing behavioral studies [Rawlins & Kessler, 1986]. Rawlins and Kessler, along with their collaborators, have continued to publish on the CS macaques.

CPRC veterinarian and future director, Matthew J. Kessler, on Cayo Santiago.

In October 1978, Windle visited CS and the SSFS. Rawlins took him and former UPR President and MSC Chancellor, Norman I. Maldonado, around the island on a nostalgic tour for Windle. This was the 40th anniversary of Carpenter's voyage from India with the monkeys for CS and Rawlins submitted an article marking the occasion [Rawlins, 1979]. A little over a year later, Windle published a detailed history of the CS colony in the journal Science that included the “Misogynist” photograph by Mieth [Windle, 1980]. He emphasized that the primate center in Puerto Rico was the model for the NIH RPRC Program. This was also confirmed in W. Richard Dukelow's “The Alpha Males: An Early History of the Regional Primate Research Centers” [Dukelow, 1995]. He was assisted in research for this book by Leo A. Whitehair of NIH, former Director of the Animal Resources Branch, who oversaw the CPRC program for many years and joined the CPRC EAC after retiring from NIH.

In 1979, Gilbert W. Meier was appointed CPRC Director. He had previously been associated with CS during the 1960s when he was a member of the LPP. Later that year, CS was hit by Hurricanes David and Federic causing some damage to the vegetation and flooding.

In May 1980, the Association of Primate Veterinarians held its 8th annual workshop in San Juan, the only one held outside of the continental US. The largest single group of primate veterinarians ever to visit CS came from this meeting.

In 1981, the city of Humacao, Puerto Rico, moved to take CS back from UPR to develop it for public recreation purposes despite the fact that the island had been expropriated for UPR over three decades before. Once all of the documents were reviewed by the Expropriation Court in San Juan, the case was dismissed. However, it made headlines in all of the local newspapers and was the subject of an editorial in El Mundo on 5 October 1981 supporting UPR's ownership of CS.

In December 1981, Rawlins left CS for Michigan State University (MSU) and Kessler managed the colony until a new Scientist-in-Charge could be found. Daily operations were handled by Angel Figueroa. With the aid of a new research assistant, John D. Berard, and an additional census taker, Edgar Davila, accuracy of the daily census was maintained despite the enormous population increase to nearly 1200 animals by the end of 1983. Under Kessler's supervision, previous management protocols were maintained and behavioral and biomedical research continued. Of particular interest was the start of annual health surveillance surveys of the CS population which examined viral and bacterial load, antibody titers, parasites, dentition, anthropometrics, degenerative disorders of the ophthalmologic and musculoskeletal systems, and diabetes.

In 1983, Rawlins organized a symposium celebrating the 45th anniversary of CS at the ASP's annual meeting at MSU. Presentations from this symposium were published in “The Cayo Santiago Macaques: History, Behavior and Biology”, a volume edited by Rawlins and Kessler [1986]. It contains a detailed history of the colony and articles on demographic, behavioral, biological and genetic research going on at that time (Fig. 54). The poem “Cayo Santiago, Home of the Rhesus Monkey” also appeared in this volume (see also annotated song in [Kessler, 1983]).

“The Cayo Santiago Macaques: History, Behavior and Biology”, published in 1986, was an edited volume by Rawlins and Kessler based on the Cayo Santiago 45th anniversary symposium held at the 6th annual ASP meeting at Michigan State University in 1983.

In early 1984, the first reduction of the CS population since 1972 occurred with the removal of three entire social groups. Groups J and M were sent to the SSFS and Group O to the German Primate Center for the founding stock of their rhesus colony. A total of 600 animals were removed representing about half of the population. Group M has been kept at SSFS for the past 30 years for a variety of behavioral and biomedical research not feasible on CS [for reviews, see Widdig et al., 2015, this issue; Zhdanova et al., 2015, this issue]. After the cull was completed, Figueroa retired and Davila replaced him as chief census taker, a position that he still holds.

At the CPRC EAC meeting in 1984, the decision to start vaccinating the CS colony against tetanus to reduce mortality and suffering in the monkeys was endorsed. At the time, tetanus was a common cause of mortality in the colony [Rawlins & Kessler, 1982] and vaccination represented a major change in the veterinary care program for the colony. Since 1985, all monkeys have been vaccinated and tetanus infections have been eliminated [Kessler et al., 1988, 2006]. This was one of the first times that a disease was eradicated from any primate population, including human [Southwick, 1989]. Thirty years later, it was shown that the tetanus vaccination program caused significant long-term effects on the demographics of the population not only affecting mortality, but life expectancy and fecundity as well [Kessler et al., 2014].

After Meier's departure from the CPRC, it was directed by a number of senior scientists from the UPR School of Medicine including physician Lloyd LeZotte, Jr. and neurobiologist Sven O.E. Ebbesson, culminating in the appointment of endocrinologist, Delwood C. Collins, from Emory University. During the Collins era from 1982 - 1985, the Division of Comparative Medicine (DCM) was established by MSC Chancellor Norman Maldonado as an umbrella unit for the CPRC, Animal Resources Center (ARC) and Collins’ new Endocrinology Laboratory. He recruited several young scientists from the states to join the CPRC including Curt Busse who served as CS Scientist-in-Charge. A major accomplishment under Busse was the computerization of the CS demographic data and development of FOXPRO-based software (Fox Software, Perrysburg, OH) that generated the monthly census, matrilines and made the data searchable to support a variety of behavioral and demographic studies. This system was used through 1999.

When Collins left, the DCM was dissolved and Kessler was appointed CPRC Acting Director and in 1986 he became CPRC Director. Some members of the scientific staff from this era are shown in Figure 55. Figure 56 shows Kessler with members of the CPRC EAC at the SSFS. With the CS operation running smoothly under the new Scientist-in-Charge, Berard, Kessler set about rebuilding the SSFS. After 16 years of exposure to the tropical elements and harsh use by the animals, the physical facilities were dilapidated. There was no decent biomedical research infrastructure or veterinary facilities. Worse, NIH grant support had been lost. Kessler restored the CPRC's P40 core grant at a significantly increased level, and combined with capitalization funds from the UPR Central Administration plus income from the sale of surplus monkeys, three new buildings were constructed at the SSFS and the corrals and pens were completely renovated using both UPR and NIAID/NINCDS breeding contract funds. These improvements essentially created a new primate center and enabled the CPRC to attain AAALAC accreditation in 1992.

John Berard, Cayo Santiago Scientist-in-Charge (1986-1999) with Susan Schwartz, Bernadette Marriott and Fred Bercovitch in 1989.

From left to right, CPRC Director Kessler with members of the Chancellor's External Advisory Committee on the CPRC: Richard G. Rawlins, W. Richard Dukelow, Leo A. Whitehair, Louis S. Harris, Kenneth P.H. Pritzker, John G Vandenbergh (Chair), Chris R. Abee, William J. Goodwin and Charles H. Southwick.

The first three year NIH core grant (l987-1990) under Kessler was renewed with two five-year continuations (1990-1995 and 1995-2000) plus several supplements. This grant gradually increased from $400,000 to almost $700,000 direct costs annually. After considerable lobbying, the Legislature of Puerto Rico also approved an annual assignment of $200,000 to the CPRC from 1987 through 1994 for a total of $1.6 million. These funds were used to support and strengthen the Center. The CPRC also received approximately $80,000 per year for an additional $600,000 from a legislative grant to UPR's Animal Health Technology Program. These funds helped support the CPRC's operation, including its diagnostic laboratory, and were used to train and recruit students from this program. From 1986 to 1999, Kessler obtained support for the CPRC totaling $10.3 million in federal grants and contracts plus $2.2 million from the Puerto Rico Legislature.

As CPRC Director, he set the program on a course that resulted in its growth and development from modest beginnings into a fully-accredited modern primate research center with three facilities (CS, SSFS and CPRC Museum). CPRC management and research programs became a national model for collaborative investigations involving both field and laboratory studies putting the CPRC in the forefront of primate research into genetics; demography; comparative diseases of aging (arthritis, osteoporosis, spondyloarthropathy, diabetes, glaucoma and macular degeneration); socioendocrinology, sociobiology and neurobiology; cognition and communicative behavior; and reproductive biology and embryology. His continued support of the CPRC Skeletal Collection allowed it to expand and become one of the world's most important research resources for osteological investigations on skeletal biology and disease, especially because of its accompanying genetic and life history databases [Dunbar, 2012; Wang, 2012; Widdig et al., 2015, this issue].

Kessler's active promotion of research activities and his ability to establish collaborations with cutting edge researchers throughout the U.S., Canada and Europe resulted in literally hundreds of publications in peer reviewed journals, and dozens of doctoral and masters theses. Some of the other highlights of this era follow.

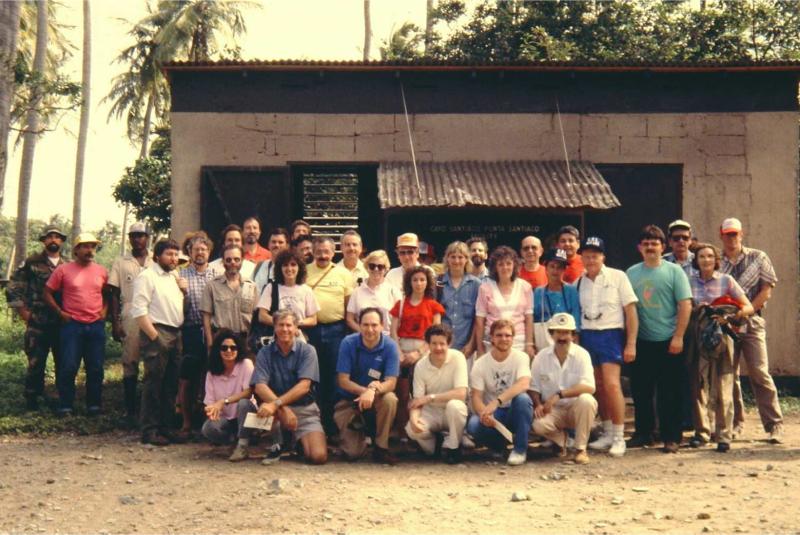

In 1988, Kessler organized an international meeting at the El Convento Hotel in Old San Juan to celebrate the 50th anniversary of CS. Over 40 dignitaries and scientists made presentations. Jaime Benitez, UPR President Emeritus, recounted the establishment of the UPR School of Medicine [Benitez, 1989], and Jose Guillermo Frontera discussed the history of CS under the LPP and the arrival and work of Stuart Altmann [Frontera, 1989]. Benitez and Whitehair are shown speaking at the meeting in Figures 57 and 58, respectively, while Figures 59 and 60 show and identify some of the attendees from the meeting who visited CS. The US Postal Service (USPS) celebrated CS's 50th anniversary with a special stamp cancellation ceremony at the CS workshop on 7 December 1988. Figure 61 shows CS Scientist-in-Charge, Berard, former Scientist-in-Charge Rawlins, CPRC Administrator Torres, and CPRC Director Kessler with USPS Postmasters. Figure 62 shows a commemorative postcard by Rawlins with the special cancellation.

President Emeritus of the University of Puerto Rico and founder of the UPR School of Medicine, Jaime Benitez, presenting his recollections at the Cayo Santiago 50th anniversary meeting in Old San Juan, December 1988.

Leo A. Whitehair, Director of the former NIH Animal Resources Branch, discussing NIH's support for Cayo Santiago and the CPRC at the Cayo Santiago 50th anniversary meeting in December 1988.

Group photograph of attendees at the Cayo Santiago 50th anniversary meeting in San Juan who visited Cayo Santiago on 7 December 1988, the 47th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. See Fig. 60 for identification key.

Key to individuals appearing in Fig. 59.

US Postal Service special stamp cancellation day on Cayo Santiago, 7 December 1988, to celebrate the colony's 50th anniversary. From left to right, US Postmaster San Juan, Kessler, Berard, Rawlins, Carlos Torres, US Postmaster Punta Santiago.

CPRC Cayo Santiago postcard with special USPS cancellation for the 50th anniversary of the colony. Photograph by Rawlins.

At the 50th anniversary, Professor Emeritus of Anatomy Frontera was honored (Fig. 63) as was Adalberto Roig, representing the Roig family that ceded CS to the STM/UPR for the colony (Fig. 64). Also honored was Angel Figueroa who was given the first ASP Senior Biology and Conservation Award by Rawlins and UPR MSC Chancellor, Jose M. Saldaña (Fig. 65).

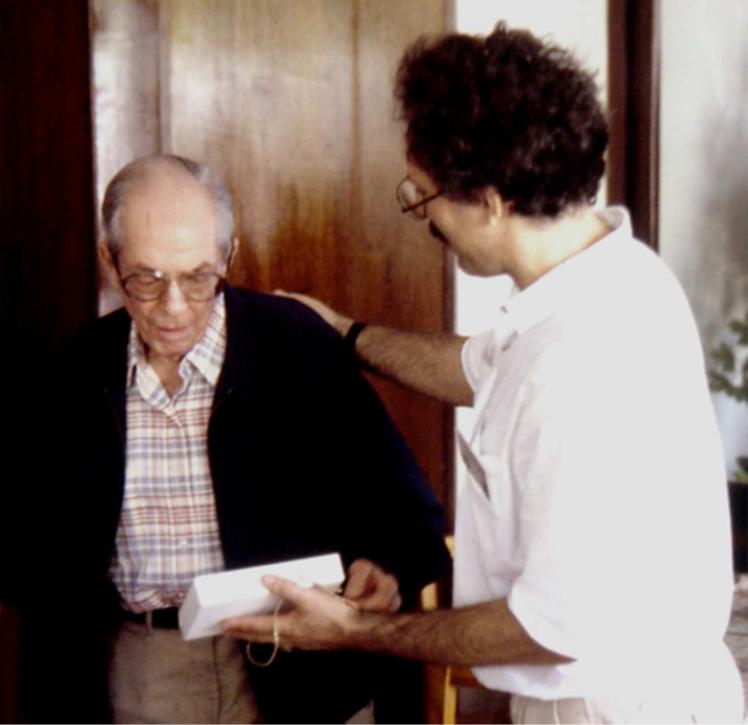

Professor Emeritus of Anatomy, UPR School of Medicine, Jose Guillermo Frontera, being honored by CPRC Director Kessler at the 50th anniversary of Cayo Santiago banquet.

Adalberto Roig, patriarch of the Roig family, being honored by CPRC Director Kessler at the Cayo Santiago 50th anniversary luncheon at Daniel's Restaurant in Punta Santiago on 7 December 1988.

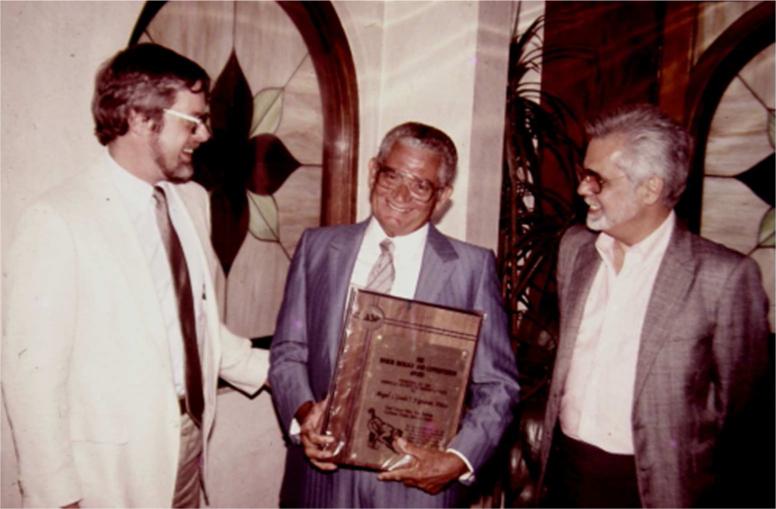

Angel “Guelo” Figueroa receiving the first ASP Senior Biology and Conservation Award from Rawlins and UPR Medical Sciences Campus Chancellor Dr. Jose M. Saldana at the Cayo Santiago 50th anniversary banquet in December 1988.

At this meeting, geneticists from the German Primate Center presented results on the DNA fingerprinting of CS rhesus shipped to their center in 1984. This led to a long-term collaboration with Joerg Schmitdke and his genetic group at the Institute of Human Genetics in Hannover beginning with Berard's studies on the life histories of CS males [Berard et al., 1993]. The collaboration has grown over the years, now encompassing several institutions, and has resulted in numerous publications [for a review, see Widdig et al., 2015, this issue].

One of Kessler's crowning achievements was compiling and editing the complete proceedings from this historic meeting for a special issue of the Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal in April 1989 [Kessler, 1989b].

On the fourth of July 1989, Saldaña and Kessler flew to Washington to meet with staff of Senators Edward “Ted” Kennedy and Bennett Johnston, and Representatives Edward Roybal and Mickey Leland from 5-7 July to discuss increased funding for the CPRC under its pending NIH P40 grant renewal. The meetings were arranged by Patricia Sosa, Legislative Director for Puerto Rico's Resident Commissioner in Congress, Jaime B. Fuster. Saldaña and Kessler also met with Antonia Coello Novello, Deputy Director of NICHD, who shortly thereafter was appointed by President George H. Bush and served as Surgeon General of the US from 1990 to 1993. They all recommended that a letter be drafted to Louis W. Sullivan, Secretary of Health and Human Services, which they agreed to co-sign with Fuster. While in the area, Kessler paid a courtesy call on Whitehair who was supportive of UPR's efforts to gain more support for the CPRC through Congressional action but who informed him that due to budget cuts the Animal Resources Program had no more money to offer the CPRC. On 11 August 1989, the letter, signed by Fuster, Johnston and Roybal was sent to Sullivan. A similar letter was sent to Sullivan by Enrique Mendez, Jr., who was Puerto Rico Secretary of Health at the time. Mendez, a retired US Army Major General and former Commander of Walter Reed Army Medical Center, was a personal friend of Sullivan and shortly thereafter was also appointed by President Bush and served as Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs from 1990 to 1993. While waiting for a response from Sullivan, Hurricane Hugo, the first major hurricane to directly hit CS since the colony was established, struck the night of 17 September 1989 (Fig. 66). Although most structures were heavily damaged or destroyed and all trees stripped of their leaves, miraculously there were no monkeys killed. The SSFS was also heavily damaged and electricity and water were not restored to Punta Santiago or SSFS for several weeks. (The ASP graciously contributed funds to help restore CS.) The only response from Sullivan was a 16 October 1989 letter to Mendez in which he first extended his sympathies to the people of Puerto Rico who suffered the devastation of Hurricane Hugo and then encouraged UPR to help the CPRC attain a “critical mass of categorically-funded research that requires use of the resource” and that the faculty at UPR MSC should “vigorously pursue the acquisition of independent research grants...” He also encouraged UPR to use the NIH Research Center's in Minority Institutions (RCMI) Program to help support the MSC's research infrastructure. This all came at a time when there were only one or two R01 grants at UPR and did not give the CPRC any expectations of receiving additional funding, especially for CS. Although the CPRC's core grant was renewed, this time for five years instead of just three, there was no significant increase in funding despite a greatly increased population size on CS.

Satellite image of the eye of Hurricane Hugo approaching Cayo Santiago the night of 17 September 1989. Courtesy of the National Hurricane Center.

In July 1990, Dan C. Williams, ARC Director, died and the Chancellor asked Kessler to also serve as its Acting Director until a replacement could be recruited. A year later, Carlos A. Malaga, who formerly ran the Iquitos Primate Center in Peru, was hired to replace Williams.

In November 1992, the CPRC hosted the NIH-supported 10th Annual Symposium on Nonhuman Primate Models for AIDS (Fig. 67). This was the first of three such symposia hosted by the CPRC. Surgeon General Novello was invited to present the keynote address, but was unable to attend. The UPR MSC had built an ABSL-3 primate research facility at the ARC and NIAID had contracted with UPR and Kraiselburd to conduct SIV research in this facility using rhesus originally from CS. It was hoped that by having over 350 scientists from 15 countries attend the symposium in Puerto Rico more AIDS-related research and collaborations with the CPRC would be forthcoming. At this meeting, the prestigious Jean Baulu collection of antique primate prints was debuted in the Americas (Fig. 68). It was subsequently exhibited at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Scientists, students and staff working at CS were invited to San Juan to view this invaluable art collection.

Program and abstracts for the 10th Annual Symposium on Nonhuman Primate Models for AIDS, one of three held in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Cover artwork by Nancy Hong, CPRC Assistant Curator and Medical Illustrator.

The Jean Baulu Collection of Antique Primate Prints was exhibited for the first time in the Americas at the 10th Annual Symposium. It was later exhibited at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Cayo Santiago's 60th anniversary's main event in 1998 was the establishment of the Dr. Louis S. Harris Endowment at UPR by Harris and his wife, Ruth, who can be seen on the right in Figure 69 with UPR President Norman Maldonado and others dignitaries. At the time, this was the largest endowment ever established at UPR boosting total donations to the CPRC for the 60th CS anniversary to about $300,000 (Fig. 70). The objective of the Harris Endowment was to provide scholarships for Puerto Rican students working on graduate degrees at the CPRC. Adaris Mas Rivera was the first recipient of the award (Fig. 71). After being mentored by Bercovitch and completing her Ph.D. on rhesus behavior at SSFS through the UPR Department of Biology, she became a Scientist-in-Charge of CS.

Signing ceremony and press conference for the establishment of the Dr. Louis S. Harris Endowment and other donations to UPR for the CPRC. From left to right, Antonio Gomez, Luis Cajiga, UPR President Norman Maldonado, Louis Harris, Ruth Harris, Anne Howard Humphrey de Tristani (standing).

San Juan Star newspaper article on the $300,000 in donations, including the Louis Harris endowment, received by UPR for the CPRC to partially mark the 60th anniversary of Cayo Santiago. Courtesy of The San Juan Star and CPRC archives.

Louis Harris and Adaris Mas Rivera, recipient of a Harris scholarship, on the Punta Santiago dock.

On 21 September 1998, Hurricane Georges passed directly over CS (Fig. 72). It was the second major hurricane to hit the island in modern times and, despite the destruction on the island similar to Hurricane Hugo 11 years earlier, again no monkeys were lost.

Satellite photograph of Hurricane Georges passing directly over Cayo Santiago on 21 September 1998. Courtesy of the National Hurricane Center.

On 11 December 1998, the USPS established a one-day “Cayo Santiago Station” to conduct a limited edition special cancellation using an envelope with a silk version of a lithograph the CPRC commissioned for the 60th anniversary showing CS and a rare golden rhesus macaque painted by famed Puerto Rican artist, Luis Cajiga. Income from the sales of these signed lithographs and specially-cancelled sets of envelopes with a new series of Caribbean birds on them (Fig. 73) were used to help support the CPRC. They were also given to UPR officials and visiting dignitaries as gifts.

US Postal Service (USPS) one-day “Cayo Santiago Station” special cancellation envelope to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Cayo Santiago colony, 11 December 1998. The postage stamp is one of four in a set of tropical birds released by the USPS in Puerto Rico in July 1998.

After 13 years, Kessler resigned as Director in April, 1999, returning to his former position as Director of Veterinary Activities, and late in 1999 Berard left Puerto Rico after an equivalent number of years as CS Scientist-in-Charge. After Berard's departure, the CS demographic data base was converted to Microsoft Access (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and now contains data on over 9,000 monkeys. Fred B. Bercovitch, who was doing collaborative research on CS with Berard and other members of the CPRC's genetic group, took over responsibility for overseeing the CS research program for about a year until Iris Velazquez was recruited in 2001 as the new Scientist-in-Charge.

In July 1999, the Director of the UPR Office of Federal and External Affairs, Anne Howard Humphrey de Tristani, niece of former U.S. Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, took Kessler and Gonzalez-Martinez to Congress and to the White House to meet with Congressmen and President Clinton's co-chairman of the Interagency Committee on Puerto Rico, Jeffrey L. Farrow (Fig. 74). The purpose of this trip was to raise awareness of some of the unique programs at the UPR MSC and to gain more federal support for the CPRC.

From left to right, Anne Howard Humphrey de Tristani, Jeffrey Farrow, Matthew Kessler, Janis Gonzalez-Martinez and Carlos Luciano at The White House, July 1999 (see text for details).

Later in the month, Malaga was appointed the CPRC's Acting Director, a position he only held until October 1999 when Bercovitch temporarily took the reins. Upon Rawlins’ recommendation, he was recruited by Kessler in 1988 from the Wisconsin RPRC to serve as a staff scientist. Bercovitch was a prolific publisher, investigator and mentor, and was now being considered for permanent CPRC Director.

However, at the annual meeting of the CPRC EAC in December 1999 (Fig. 75), the members were informed that Edmundo Kraiselburd, PhD, a UPR virologist with research experience in dengue fever and SIV/HIV/AIDS vaccine development using macaques, was going to be appointed as the new permanent CPRC Director and that the former Division of Comparative Medicine was going to be resurrected as the Unit of Comparative Medicine (as “Division” in Spanish has bad connotations). At this meeting, the first of 15 annual CPRC calendars produced by Rawlins and fellow photographer, Zvi Binor, was debuted (Fig. 76).

CPRC External Advisory Committee dinner at El Zipperle Restaurant, December 1999. Standing left to right: Leo Whitehair, Chancellor Pedro Santiago Borrero, Edmundo Kraiselburd, Ronald Desrosiers, Louis Harris, Keith Mansfield, Matthew Kessler, Sarah Williams-Blangero, Richard Rawlins. Seated from left to right: Mrs. Whitehair, Manfield, Desrosiers and Dukelow, and W. Richard Dukelow (Chair)

The first of 15 annual calendars (1999-2014) produced by Richard Rawlins and Zvi Binor for the CPRC. The 2013 version was distributed to all attendees at the 36th annual meeting of the ASP in San Juan.

In January 2000, Kraiselburd was appointed Director and Kessler was asked to serve as Associate Director. At the December 2000 meeting of the CPRC EAC, he was honored for his service as CPRC Director (Fig. 77). When he retired from UPR in 2001, Gonzalez-Martinez was appointed to this position, one she held until late 2013. She worked closely with Kraiselburd (Fig. 78) during these dozen years helping to bring in millions of dollars of NIH funds to the CPRC and overseeing its daily operations.

Former CPRC Director Kessler receiving a distinguished service plaque from External Advisory Committee Chair, Dukelow; Chancellor Santiago Borrero and incoming CPRC Director Kraiselburd, December 2000.

CPRC Director Kraiselburd and Associate Director, Gonzalez-Martinez at work.

In 2001, the CPRC co-hosted the 19th Annual Symposium on Nonhuman Primate Models for AIDS in San Juan with the New England PRC.

From 2001-2007, Melissa S. Gerald served as CS Scientist-in-Charge. She obtained a Leakey Foundation grant and attracted a number of new investigators to CS including Laurie Santos from Yale, Michael Platt and Lauren Brent from Duke, and Dario Mastripieri from the University of Chicago whose master's dissertation student, Angelina Ruiz-Lambrides, became colony manager at SSFS and eventually CS Scientist-in-Charge collaborating with Anja Widdiq and her colleagues in Europe. During these years the focus of the CS culls was to provide monkeys for the SPF colonies established at the SSFS.

In 2006, the Chancellor invited Kessler to join the CPRC EAC on which he served with co-author Rawlins and others through 2013.

The 70th anniversary of CS in December 2008 coincided with the 100th anniversary of the birth of former UPR President Jaime Benitez and the annual Christmas concert at the Luis A. Ferre Performing Arts Center (“Bellas Artes”), Puerto Rico's premier performing arts center. Kraiselburd (Fig. 79) organized a gala event there in conjunction with the 26th Annual Symposium on Nonhuman Primate Models for AIDS, co-hosted by the CPRC and Wisconsin NPRC. This was the third time the meeting was held in San Juan. A benefit of having these meetings in Puerto Rico is that the CPRC and UPR had an opportunity to showcase CS and establish more collaborations. A good example occurred recently when Francoise Barre-Sinoussi of the Pasteur Institute, who was co-awarded the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her co-discovery of HIV in 1983, visited CS. In Figure 80, she is shown receiving a Cajiga CS lithograph from Kraiselburd and Gonzalez-Martinez after touring CS and giving a lecture on HIV/AIDS at the UPR School of Medicine in December 2011. She had previously attended the three symposia in San Juan. This visit resulted in Kraiselburd spending a sabbatical in Barre-Sinoussi's laboratory in France.

CPRC Director Kraiselburd at the reception for the 26th Annual Symposium on Nonhuman Primate Models of AIDS with Cayo Santiago 70th anniversary cake, December 2008. Photograph by Kessler.

CPRC Director Kraiselburd and Associate Director Gonzalez-Martinez presenting Francoise Barre-Sinousi with a Cayo Santiago lithograph by Luis Cajiga after her AIDS lecture at the UPR School of Medicine in December 2011. Photograph by Kessler.

For the 70th anniversary, Rawlins published “Cayo Santiago Macaques - Images” (Fig. 81), a book based on his CS photographs from 1972 – 2008. The volume also contains a brief history of the colony ([Rawlins, 2009]; http://www.blurb.com/b/898239-cayo-santiago-macaques-images) The American Association of Physical Anthropologists also commemorated the 70th anniversary of the establishment of the CS colony by holding a symposium at its 78th annual meeting in Chicago on 2 April 2009. Figure 82 shows the speakers whose papers were published in the volume “Bones, Genetics, and Behavior of Rhesus Macaques: Macaca mulatta of Cayo Santiago and Beyond” edited by Qian Wang [Wang, 2012].

“Cayo Santiago Macaques - Images” published by Rawlins to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the colony contains photographs taken by him from 1972 through 2008.

Qian Wang, right, with presenters at the Cayo Santiago 70th symposium he organized at the 78th annual meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists held in Chicago on 2 April 2009. The papers were published in a 2012 volume Wang edited. See text for details.

The 75th anniversary of the CS colony was commemorated in June 2013 by holding the 36th Annual Meeting of the ASP in San Juan (Fig. 83) at which three symposia Cayo Santiago: 75 Years of Leadership in Translational Research, Cayo Santiago: Studies in Development and Physiology, and Circadian Rhythms In Non-Human Primates and Their Modulation of Physiological Functions were held. In addition, Carol Berman delivered a featured address on primate kinship, and a number of other papers and posters on CS research were presented. On 18 June, ASP members toured CS in the largest assembly of visitors to the island in its history (Figs. 84-86). The idea for having this meeting in Puerto Rico was conceived by Gonzalez-Martinez who was in charge of local arrangements and organized at least one of the CS symposia.

Program and abstracts for the 36th annual meeting of the ASP held in June 2013 in San Juan to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Cayo Santiago colony. AJP cover photograph by Rawlins.

Current satellite or aerial photograph of Cayo Santiago. Courtesy of Google Earth.

One of many groups of ASP meeting attendees who toured Cayo Santiago on 18 June 2013.

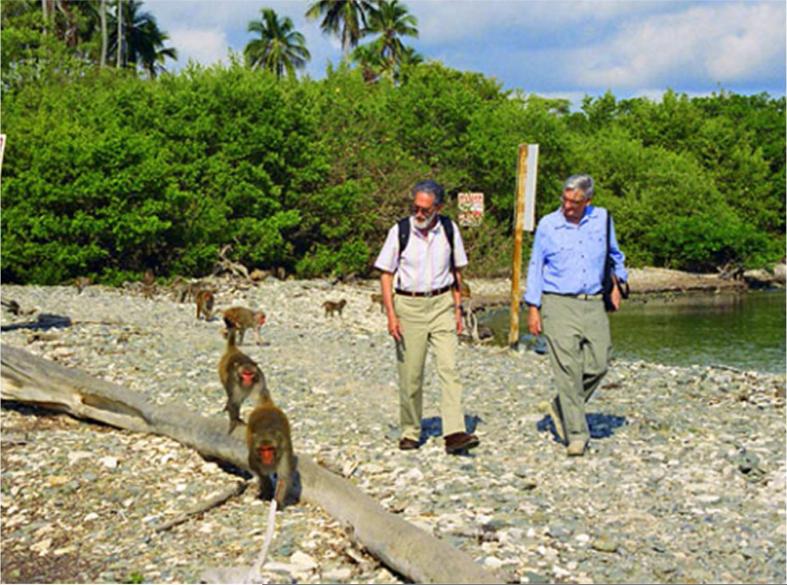

Of those who worked on CS when the colony was founded, only one is still alive. In September 2007, the authors were very fortunate to meet 81-year-old Ismael Solis Arroyo at the CPRC's office in Punta Santiago (Fig. 87). Solis, who is now in his late 80s, began work on CS in mid-November 1938 at the age of 12 as Michael Tomilin's boatman and as an animal caretaker. He also helped plumb the 10,000 gallon water cistern on the Big Cay hill shortly before he left work on CS in 1941 (I. Solis Arroyo, pers. comm., 5 June 2007). He told stories about the early days of the colony including how the monkeys survived WWII food restrictions and how he hid behind bushes to help Tomilin trap monkeys for tuberculosis testing and tattooing using banana-baited cages (Fig. 88). He also divulged anecdotes about Carpenter, the Tomilins and their pet monkey (“Pijita”), their living quarters in the wooden house on CS, and verified some tall tales about Tomilin, “The Monkey Man” [Dorvillier, 1986]. The authors were able to video record two interviews with him, and to take him on a nostalgic tour of CS. He had not been on the island for about 70 years. Figure 89 shows him standing in front of the rock where the Tomilins used to sit in the early 1940s with their pet monkey (Fig. 25).

Former CPRC Director Kessler (left) and former Cayo Santiago Scientist-in-Charge Rawlins, both members of the CPRC External Advisory Committee at the time, meeting with former Cayo Santiago boatman and animal caregiver from the late 1930s and early 1940s, Ismael Solis Arroyo. in September 2007. He was given a copy of their book and a Cayo Santiago lithograph.

Typical cage used to capture Cayo Santiago monkeys for tuberculosis testing and other purposes during the early days of the colony. Courtesy archives of the Caribbean Primate Research Center.

Ismael Solis standing in front of the “Tomilin Rock” on Cayo Santiago during his nostalgic tour of the island in September 2007 after about a 70 year absence. Photograph by Kessler.

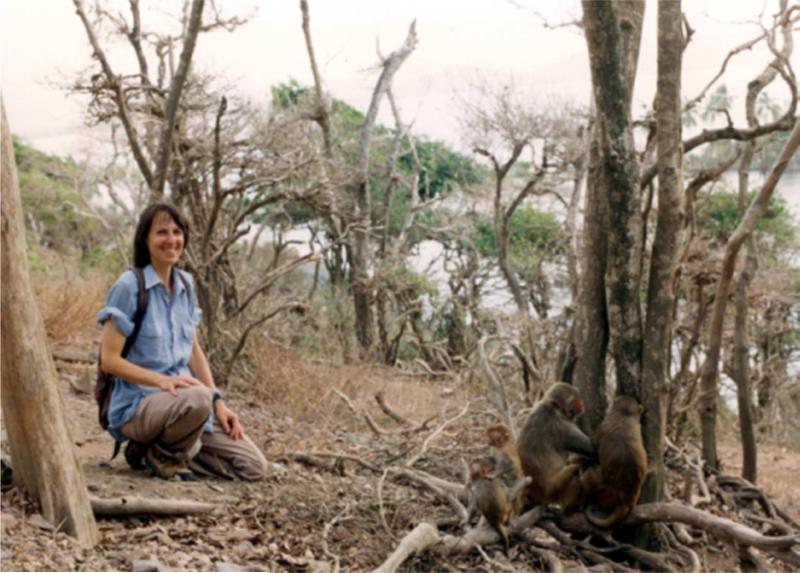

The CS colony has been supported by NIH and UPR for many years, as well as by NSF from time-to-time. Besides institutional support, the monkeys have been cared for by a truly dedicated team of workers and census takers, and supported by an extensive network of “Cayo Santiago alumni” over the years such as Carol Berman (Fig. 90), who conducted her doctoral dissertation research on CS in the 1970s and has continued to study mother-infant relations and behavior over several generations [Berman, 2015; this issue]. Other research teams led by investigators such as Stephen Suomi, Dario Maestripieri, Michael Platt, Lauren Brent, Laurie Santos and Anja Widdig have also promoted the value of the colony for behavioral and genetic studies [see Brent et al., 2015, this issue; Maestripieri et al., 2015, this issue; Widdig et al., 2015, this issue]. Other scientists, who started research on CS and then moved to the SSFS to conduct more detailed studies with CS-derived rhesus, have also supported CS. Several examples from the past few decades are the investigations by the William W. Dawson (Fig. 91) and his group on adult-onset macular degeneration and glaucoma [Dawson et al., 2008], Kenneth P.H. Pritzker and his group on arthritis and bone disease [Pritzker & Kessler, 2012], Charles F. Howard, Jr. on diabetes and metabolic disease [Howard et al., 1990] and, most recently, on circadian rhythm disorders [Zhdanova et al., 2012, 2015 this issue]. Still others, such as Turnquist (Fig. 92), Cerroni and Wang, have conducted extensive research using the CS skeletons [for reviews, see Wang, 2012; Widdig et al., 2015, this issue].

Carol Berman observing mother-infant behavior on Cayo Santiago as part of her multi-generational studies.

William W. Dawson studying the macula of the retina of a Cayo Santiago-derived rhesus monkey at the CPRC's Sabana Seca Field Station.

Jean E. Turnquist, UPR School of Medicine Professor of Anatomy and former Curator of the CPRC Skeletal Collection, demonstrating bones from a Cayo Santiago rhesus macaque.