Abstract

We continuously receive the external information from multiple sensors simultaneously. The brain must judge a source event of these sensory informations and integrate them. It is thought that judging the simultaneity of such multisensory stimuli is an important cue when we discriminate whether the stimuli are derived from one event or not. Although previous studies have investigated the correspondence between an auditory-visual (AV) simultaneity perceptions and the neural responses, there are still few studies of this. Electrophysiological studies have reported that ongoing oscillations in human cortex affect perception. Especially, the phase resetting of ongoing oscillations has been examined as it plays an important role in multisensory integration. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship of phase resetting for the judgment of AV simultaneity judgement tasks. The subjects were successively presented with auditory and visual stimuli with intervals that were controlled as and they were asked to report whether they perceived them simultaneously or not. We investigated the effects of the phase of ongoing oscillations on simultaneity judgments with AV stimuli with SOAs in which the detection rate of asynchrony was 50 %. It was found that phase resetting at the beta frequency band in the brain area that related to the modality of the following stimulus occurred after preceding stimulus onset only when the subjects perceived AV stimuli as simultaneous. This result suggested that beta phase resetting occurred in areas that are related to the subsequent stimulus, supporting perception multisensory stimuli as simultaneous.

Keywords: Simultanity judgement, Phase resetting, Electroencephalograpy, Intertrial coherence

Introduction

When a falling cup smashes on the floor and simultaneously emits a breaking sound, humans generally receive multisensory inputs from the single event. The brain aims to explain which event generates each type of sensory information and integrate them in an appropriate manner in order to construct unified recognition. It is thought that judging the simultaneity of such multisensory stimuli is an important cue when we discriminate whether the stimuli are derived from one event or not. In addition, it is a common hypothesis that the perception of simultaneity depends on the temporal differences of the onsets of the stimuli, which is called stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA).

In psychological studies, it is known that the detection rates of asynchrony are plotted in a psychometric curve that is related to SOA in auditory-visual (AV) simultaneity judgment tasks (AV SJ task) (Stone et al. 2001; Vroomen and Keetels 2010). The AV SJ task is a psychological experiment in which auditory and visual stimuli with various SOAs are presented to subjects. In this task, subjects are asked whether they perceive the stimuli as simultaneously presented or not. It is known that exists in which the judgment rate of asynchrony is 50 % even though the stimuli are presented with a constant physical time difference. This indicates that subjective simultaneity judgment is influenced by external factors and the internal states of the subjects. Bushara et al. (2001) have revealed correlations between SOA lengths and post stimulus activations in the right insula by positron emission tomography. In addition, Franciotti et al. (2011) have indicated that the latencies of magnetoencephalogram responses in the auditory cortex after auditory stimuli correlate with the detection rates of asynchrony. Although these studies have investigated the correspondence between AV simultaneity perceptions and the neural responses, there are still few studies of this.

In electrophysiological studies, it has been reported that ongoing oscillations in human cortex affect perception (Babiloni et al. 2006; Hanslmayr et al. 2007; Romei et al. 2010). In addition to oscillatory amplitude, its phase is involved in visual processing (VanRullen and Koch 2003; Busch et al. 2009; Mathewson et al. 2009; Dugue et al. 2011). Especially, the phase resetting of ongoing oscillations has been examined as it plays an important role in multisensory integration. This is a phenomenon in which the oscillations in a certain sensory cortex are reorganized into a particular phase by a sensory input. The phase resetting is induced by not only a preferred stimulus but also by another modality stimulus. It has been reported that a sensory input to the somatosensory cortex resets the phase of oscillations in the auditory cortex and amplifies neuronal responses to the auditory stimulus (Lakatos et al. 2007). Recent studies in primates have described that the phase reset is bidirectional and is both AV and visual-auditory (VA) (Kayser et al. 2008; Lakatos et al. 2009). These findings implicate that the phase resetting that is induced in the sensory area, which does not concern the modality of the input stimulus, plays a profound role in multisensory interaction.

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship of phase resetting for the judgment of an AV SJ task. In this study, the subjects were successively presented with auditory and visual stimuli with intervals that were controlled as and they were asked to report whether they perceived them simultaneously or not. Electroencephalography (EEG) signals were recorded from the subjects, and the phase resetting of EEG oscillations was analyzed by Intertrial Coherence (ITC).

Materials and methods

Subjects

Fifteen healthy males with ages of 20–24 years [mean standard deviation (SD) age, 22.2 2.2] participated in this study. All participants gave their written informed consent. They were all right-handed and had normal hearing and normal or corrected-normal vision. The data of fourteen subjects out of the participants were analyzed because the EEG data of one subject could not be used because of artifacts.

Stimuli

For the auditory stimulus, a pure 2000 Hz pip tone with a 10 ms duration was presented binaurally through earphones (G051; Daiso industry). The intensity of the auditory stimulus was loud enough to be heard (sound pressure level, 61 dB). The visual stimulus consisted of a white ring flash subtending 3.8° in the visual angle that was 4 cm in diameter and that was presented on a black background for 16 ms. A white fixation cross was continuously displayed on the center of the screen. These visual presentation were conducted through the display (DELL P1137; refresh rate, 60 Hz) at a distance of 60 cm from the subjects. During the experiment, the course of events was controlled by the psychophysics Toolbox on MATLAB R2010b.

EEG recordings

The electrophysiological data were recorded by electroencephalography machine (EEG-1200; Nihon Kohden Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) containing 57 electrodes. The electrode layout was modified from the 10–20 system, and reference electrodes were attached to both earlobes. The data were recorded with a sampling rate of 500 Hz. Electrode impedances were kept at <10 kΩ. Vertical and horizontal electrooculograms were simultaneously recorded.

Task procedure

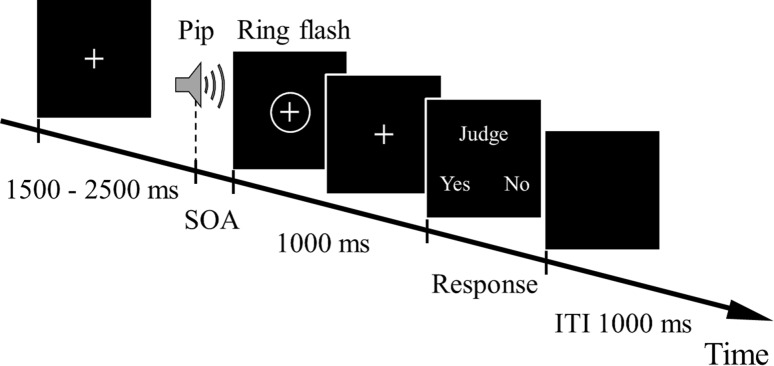

Subjects performed the AV SJ task (Fig. 1) in a silent and dimly lit room that was surrounded by an electrical shield. Hereafter, the case in which the auditory stimulus was presented first is the AV condition, and the converse is the VA condition. The procedure of the AV SJ task was as follows.

A fixation point was presented on the center of the screen.

After a random duration between 1,500 and 2,500 ms, the pip tone and the ring flash were presented with SOA.

After 1,000 ms, the judge screen was displayed. Then the subjects reported whether they perceived them as simultaneous (“ Yes”) or not (“No”) by pressing one of the two buttons with their right index or middle finger. The direction of the “Yes” button was to the left from subjects 1–8. After subject 9, the direction was reversed.

After the subject’s response, the black screen was presented for 1,000 ms as an intertrial interval. Then, one trial was over.

In this experiment, 1 block consisted of 60 trials. Rest was provided to the subjects after completion of a block, and it was finished by pressing an arbitrary button.

Fig. 1.

Time flow of the present experiment [auditory-visual (AV) condition]. In the visual-auditory (VA) condition, a ring flash was presented first. Subjects were asked to report whether the stimuli were simultaneous or not in the judgment screen by pressing a button

Preliminary experiment

For the titration, we conducted a preliminary experiment before the start of the EEG session. The procedure of this session was the same as that shown in Fig. 1. Auditory and visual stimuli were presented with an SOA that was randomly selected from 12 different SOAs (16, 60, 120, 180, 240, or 300 ms for each AV and VA condition). The preliminary experiment consisted of 3 blocks for a total of 15 trials per SOA. At the end of the session, psychometric curves of the detection rate of asynchrony were estimated for each condition. Then, the and the of each subject were determined. The was the SOA rate in which the subject felt that nonsimultaneity became 95 %. For psychometric curves fitting and estimation, we used generalized linear model functions in Matlab.

Main experiment

In the EEG session, we adopted an SOA that was randomly selected for each trial of the AV SJ task (six options for SOA: 16 ms, and for each AV and VA condition). The SOA of 16 ms and were used to prevent adaptation to the SOA (Fujisaki et al. 2004) and for a catch trial. This session consisted of 6 blocks for a total of 360 trials. was presented for 90 trials for each AV and VA condition, and the other 180 trials were divided equally among the other SOAs.

Data analysis

We used Matlab R2010b (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) for the data analysis. The Electrophysiological data for the trial were classified by the conditions and the responses of the subject: AV-YES, AV-NO, VA-YES, or VA-NO. An automatic artifact rejection excluded trials in which the EEG signal exceeded .

A wavelet transform from 1 to 50 Hz in steps of 0.5 Hz was applied to each data point (Torrence and Compo 1998; Le Van Quyen and Bragin 2007). The parameter of was 6.

In order to evaluate the phase properties, we calculated the ITC of each AV-YES, AV-NO, VA-YES, and VA-NO condition (Busch et al. 2009).

| 1 |

N is the number of trials, and is the phase at time t and frequency f. ITC indicates the phase concentration among all of the trials. The value of 1 indicates perfect phase locking, while 0 indicates random phase distribution.

We used the t test in the statistics toolbox in Matlab as the statistical test of these values. And we adopted the FDR method (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995) for multiple comparisons. Before the statistical analysis, the wavelet amplitude and the ITC data were normalized. The baseline for normalization and plotting was the average of the 300 ms EEG data whose variance was the minimum within the intertrial interval.

Results

Behavioral data

For the preliminary experiment, the mean ± SD for all of the subjects was ms in the AV condition and ms in the VA condition.

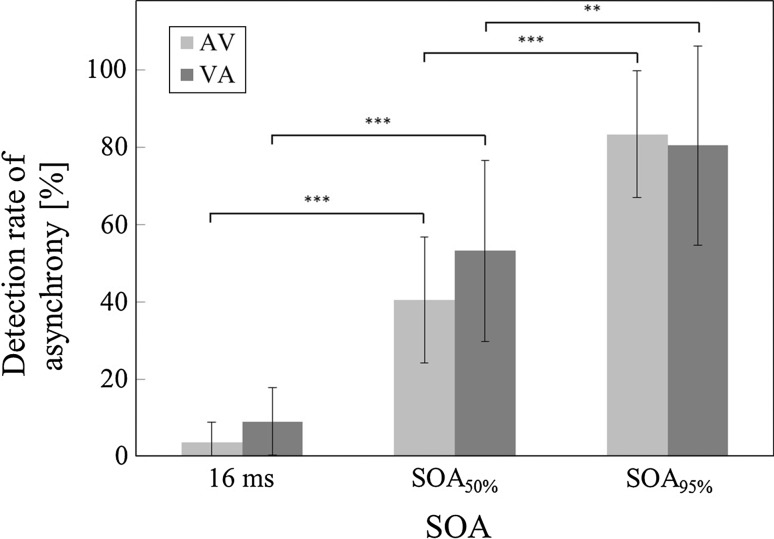

In the EEG session, the mean detection rates for all of the subjects at became for the AV condition, and for the VA condition. These values were consistent with those of previous studies (Fujisaki et al. 2004; Zampini et al. 2005). The detection rates of asynchrony were increased according to the length of the SOA (Fig. 2). The statistical test showed significant differences between all of the combinations of detection rates in the respective conditions (p < 0.01). Hence, it was thought that the subjects did not press the buttons at random but did so according to their perception of simultaneity.

Fig. 2.

The asynchrony detection rates in each stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) in the main experiment. The bar shows the standard deviation (SD). '*' Indicates significance, ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01

Under the condition, we would like to emphasize that the simultaneity perception is not decisive but rather fluctuating. Our aim is to clarify the EEG state, which will affect the discrimination of subtle simultaneity. Although the mean asynchrony detection 40 % for AV, deviated from 50 %, may possibly affect EEG data, most data which reflect the behavior will not be affected. This is because behaviorally the detection rate in significantly differs from 16ms and SOA95 %, respectively.

ITC enhancement with simultaneity perception

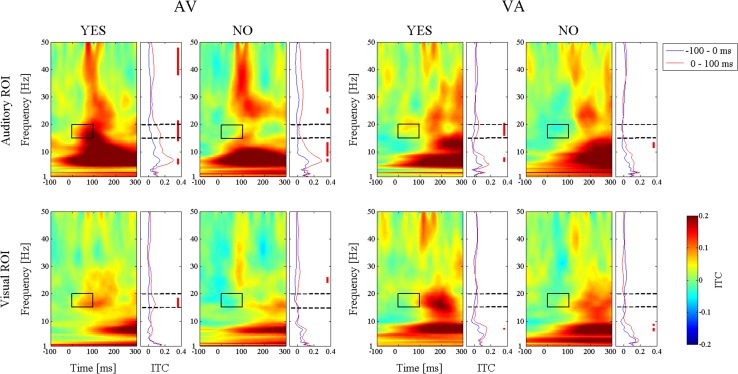

In order to focus on the activity that was evoked by the visual and auditory stimuli, we determined the following regions of interest (ROI). The auditory ROI covered the electrodes on the central area of the scalp (FC1, FC2, FCz, C1, C2 and Cz) and the visual ROI was located in the occipital area (PO3, PO4, POz, O1, O2 and Oz). In Fig. 3, ITC enhancements were observed in a wide frequency band after onset of the preceding stimulus in both conditions regardless of the subject’s perception. In order to investigate the ITC modulations that were purely induced by the preceding stimulus, the time averaged ITC values were compared. The right panels in Fig. 3 show the prestimulus ITC, which was time averaged from −100 to 0 ms (blue line), and the poststimulus ITCs, which was time averaged from 0 to 100 ms (red line). The red bars on the right edge indicate that the poststimulus ITC was significantly larger than the prestimulus ITC. As shown in Fig. 3, we found significant ITC modulations for the time averaged ITCs before and after the prestimulus and the poststimulus periods. Since there are only three values <100 ms and the smallest is 83.4 ms (Table 1), the data during 0–100 ms period in Fig. 3 are hardly affected by the second stimulus.

Fig. 3.

Colormaps showing the time-frequency plots of the intertrial coherence (ITC). 0 ms is the stimulus onset. Baseline was subtracted and the value was averaged across all subjects and the electrodes of each auditory and visual region of interest (ROI). The auditory ROI contains FC1, FC2, FCz, C1, C2 and Cz, and the visual ROI contains PO3, PO4, POz, O1, O2 and Oz. The line plots on the right of the colormaps are the time-averages of the pre- and poststimulus ITC. The blue line is the ITC that was averaged from −100 to 0 ms (prestimulus), and the red line is from 0 to 100 ms (poststimulus). The red bar indicates significant enhancement of the poststimulus ITC compared to the prestimulus (p < 0.05). The conditions and responses of the subjects are horizontally organized. The upper line shows the auditory ROI and the lower is the visual ROI. The box surrounds the poststimulus ITC modulation in the beta frequency band (15–20 Hz, 0–100 ms)

Table 1.

values for all subjects for AV and VA conditions

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV | 225.3 | 138.5 | 142.5 | 119.4 | 114.7 | 146 | 151.8 | 213.9 | 228.7 | 242.1 | 146 | 215.8 | 106.7 | 120.2 |

| VA | 142.8 | 142.5 | 215.3 | 132.3 | 83.4 | 91.4 | 107.7 | 142.2 | 300 | 163.3 | 94 | 121.1 | 146.6 | 164 |

The label number indicates a subject

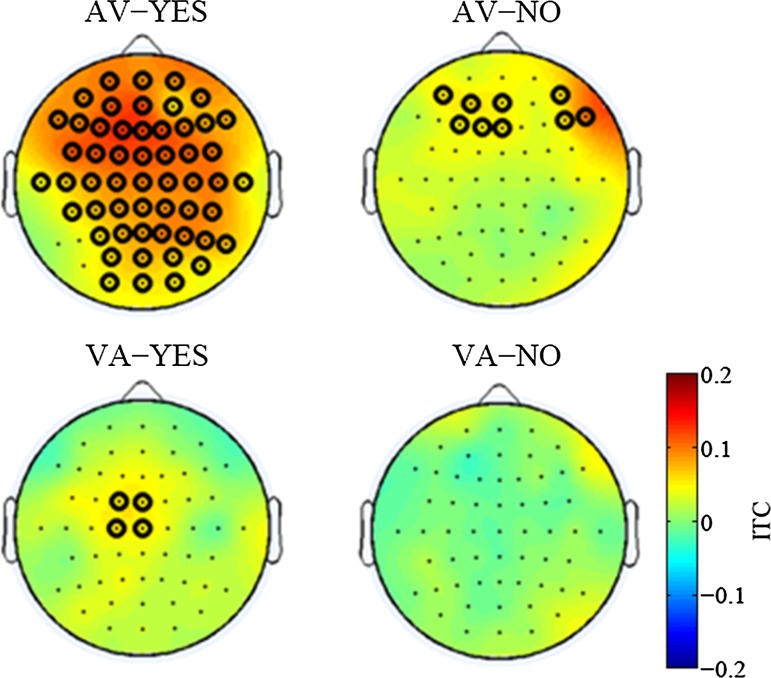

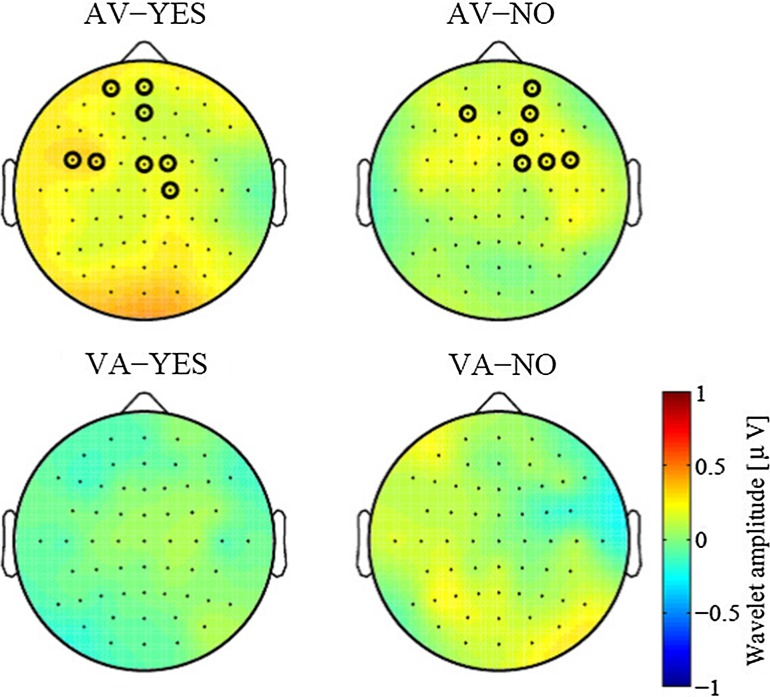

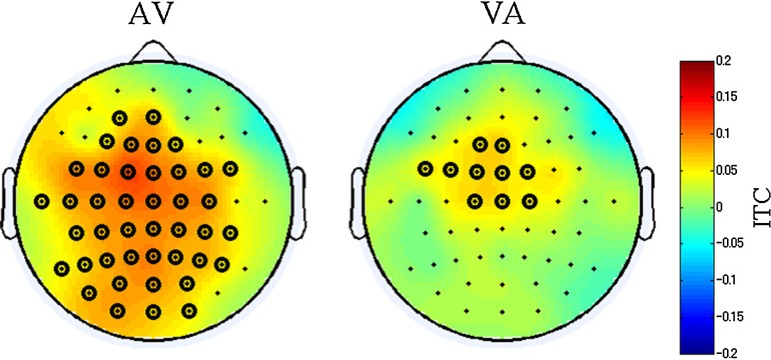

We searched for perception specific ITC modulations that were common to both the AV and the VA conditions and observed that the beta band of the poststimulus ITCs in the ROIs that were related to the following stimuli were significantly enhanced only when the subjects responded ”YES” (Fig. 3). In Fig. 4, the ITC increase of the beta frequency band is displayed topographically. The beta ITC increase was seen in a large brain area that include the visual ROI in the AV-YES condition. In the VA-YES condition, the ITC was enhanced in the frontocentral region, which included the auditory ROI. However, such an ITC increase did not appear in both the AV-NO and VA-NO conditions. In ERP analysis, significant differences between Yes and No for simultaneity were not observed (results are not shown in the paper). Thus, this coherence cannot be captured by ERP, but ITC especially.

Fig. 4.

The topography of the poststimulus ITC in the beta frequency band. The time-frequency section of topography is the same as the box in Fig. 3. The black rings show electrodes that indicated a significant ITC enhancement from the prestimulus (−100 to 0 ms, 15–20 Hz) (p < 0.01). The upper line is the AV condition, and the lower is the VA condition. The responses of the subjects are horizontally organized

Wavelet amplitude modulation accompanied with a beta ITC increase

Previous studies have argued that phase resetting in the true sense is not accompanied by change in power. In order to test the poststimulus modulation of the beta band power, we also checked the wavelet amplitude at the same time-frequency section as shown in Fig. 4. The results are shown in Fig. 5. In the AV condition, there was no significance in the visual ROI (p > 0.2), though power enhancements were observed at several electrodes in the frontal and central areas in both ”YES” and ”NO”. In the VA condition, no electrode in the auditory ROI showed significant similarly (p > 0.2). Thus, the beta ITC increment that occurred in the ROI of the modality of the second stimulus was not accompanied by power modulation.

Fig. 5.

The topography of the wavelet amplitude modulation by the first stimulus. The compared time-frequency section is the same as that in Fig. 4 (0–100 ms vs. −100 to 0 ms of 15–20 Hz). There were few black rings indicating a significant increased amplitude (p < 0.05) even without FDR correction

Beta ITC comparison between simultaneity and nonsimultaneity

In Fig. 4, the characteristic significant enhancement of ITC in the beta frequency band is shown only when the subject judged ”Yes”. In order to confirm that the value of ITC had difference between ”Yes” and ”No” in each condition, we tested the poststimulus ITC (Fig. 6). As a result, many electrodes in a large area including the visual and auditory ROI had greater ITC values in AV-YES than in AV-NO (p < 0.01). Similarly, electrodes in the auditory ROI showed a significant difference between VA-YES and VA-NO (p < 0.01). Thus, the beta band ITC in the brain areas that preferred the following stimulus was significantly enhanced when the subjects perceived simultaneity compared to when the subjects did not.

Fig. 6.

The difference of the beta ITC in the poststimulus period between ”Yes” and ”No” of each condition (0–100 ms, 15–20 Hz). The left topography is the AV condition, and the right is VA. The black ring shows the electrode that had a greater ITC value in ”Yes” than in ”No” (p < 0.05)

Discussions

We assume that the perception of simultaneity should reflect a common cortical state under every stimulus condition such as AV or VA. From this viewpoint for simultaneity perception, we should note that ITC increased in visual ROI immediately after auditory stimulus in AV condition while it symmetrically increased in auditory ROI immediately after visual stimulus in VA condition. Although the ITC enhancement in auditory ROI in AV condition may also affect simultaneity perception, we cannot exclude the possibility of side effects observed only in the AV condition because it is not the case with VA conditions. On the other hand, in visual ROI of VA, we observed ITC increase for simultaneity around t = 200 ms period, that may include both effects of the stimuli. Thus we cannot decide whether this reflects mainly auditory stimulus or both stimuli. If the auditory stimulus is the main cause, it may be possible to assume that delayed phase resetting occurs in visual ROI by the auditory stimulus. However, this hypothesis cannot be proved by the present study.

In both the AV and the VA conditions, a high coherence of phase was observed in the brain regions that correlated to the second stimulus modalities when the subjects perceived that the auditory and visual stimuli were simultaneous. In addition, the wavelet amplitude was significantly enhanced in the fronto-central brain area only in the AV condition.

ITC enhancement by the preceding stimulus

ITC enhancements that are induced by sensory stimuli have been interpreted as phase resetting in previous studies. However, ITC increases that were accompanied by oscillatory power enhancements have not been considered modulatory responses but evoked responses (Lakatos et al. 2009). In the present results, the beta phase resets in the brain areas that preferred the modality of the following stimulus were not accompanied by oscillatory power modulations. Thus, it was thought that pure beta phase resetting occurred by the preceding stimulus in the area that related to the modality of the following stimulus only when the subjects perceived AV stimuli as simultaneous regardless of the stimulus order.

The effect of phase reset on simultaneity judgment

Previous studies have suggested that phase reset has modulatory effects on the states of the sensory cortices (Lakatos et al. 2009). Lakatos et al. (2007) and Naue et al. (2011) have shown that neuronal responses for the following preferred stimulus were enhanced when the phase resetting in the sensory cortex had been caused by the preceding stimulus of the nonpreferred modality.

Actually, Busch et al. (2009) and Dugue et al. (2011) have shown that the phase of the ongoing oscillation affects human perception. Thus, it is thought that the process of perception may be affected by the phases that are modulated by the previous sensory inputs. The present study demonstrated that the phase coherence in the beta frequency band after the preceding stimulus was significantly higher when the subject’s perception was of simultaneity than when it was asynchronous. Previous studies have also suggested that the beta frequency band plays an important role in multisensory integration (Sakowitz et al. 2005; Senkowski et al. 2006; Keil et al. 2012). Naue et al. (2011) have shown that the power modulation of the beta frequency band in the visual area varied with SOAs between the preceding auditory stimulus and the subsequent visual stimulus. The beta frequency band relates to AV integration of asynchronous stimuli. If it is true, it is thought that the beta phase resetting that is induced by the preceding stimulus affects the nervous simultaneity judgment on . A conceivable hypothesis about how phase resetting affects simultaneity judgment is that it modulates the state of oscillation in the reset area (Lakatos et al. 2009). The mutual influence of two oscillators may depend on their phase states (for example, Fries 2005). If the oscillatory cortices in auditory (visual) regions become coherent accompanied by the phase resetting by the visual (auditory) stimulus, auditory and visual information would be immediately integrated at the moment when the second stimulus is input. Hence the subject may feel the inputs to be simultaneous.

Alhough these discussions are conceivable, ITC enhancement in fronto-central scalp areas was observed in the AV-YES condition. The possibility that phase resetting in the frontocentral area affected AV SJ cannot be ruled out. However, ITC increments at frontocentral areas in the AV-YES condition were accompanied by wavelet power enhancements (see Fig. 5). A previous study has shown that auditory stimuli evoke beta activity in the frontocentral area (Haenschel et al. 2000). It is thought that ITC enhancements at the frontocentral area in the AV-YES condition might include evoked responses.

Conclusion

In the present study, we investigated the effects of the phase of ongoing oscillations on simultaneity judgments with AV stimuli with SOAs in which the detection rate of asynchrony was 50 %. Our results showed that phase resetting at the beta frequency band in the brain area that related to the modality of the following stimulus occurred after preceding stimulus onset only when the subjects perceived AV stimuli as simultaneous. Therefore, these results suggested that beta phase resetting occurred in areas that are related to the subsequent stimulus, supporting perception of multisensory stimuli as simultaneous.

References

- Alho K, Woods DL, Algazi A, Knight RT, Naatanen R. Lesions of frontal cortex diminish the auditory mismatch negativity. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;91(5):353–362. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(94)00173-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiloni C, Vecchio F, Bultrini A, Luca Romani G, Rossini PM. Pre- and poststimulus alpha rhythms are related to conscious visual perception: a high-resolution EEG study. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(12):1690–1700. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Busch NA, Dubois J, VanRullen R. The phase of ongoing EEG oscillations predicts visual perception. J Neurosci. 2009;29(24):7869–7876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0113-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushara KO, Grafman J, Hallet M. Neural correlates of auditory-visual stimulus onset asynchrony detection. J Neurosci. 2001;21(1):300–304. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00300.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugue L, Marque P, VanRullen R. The phase of ongoing oscillations mediates the causal relation between brain excitation and visual perception. J Neurosci. 2011;31(33):11889–11893. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1161-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franciotti R, Brancucci A, Della Penna S, Onofrj M, Tommasi L. Neuromagnetic responses reveal the cortical timing of audiovisual synchrony. Neuroscience. 2011;193:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P. A mechanism for cognitive dynamics: neuronal communication through neuronal coherence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9(10):474–480. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisaki W, Shimojo S, Kashino M, Nishida S. Recalibration of audiovisual simultaneity. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(7):773–778. doi: 10.1038/nn1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenschel C, Baldeweg T, Croft RJ, Whittington M, Gruzelier J. Gamma and beta frequency oscillations in response to novel auditory stimuli: a comparison of human electroencephalogram (EEG) data with in vitro models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(13):7645–7650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120162397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanslmayr S, Aslan A, Staudigl T, Klimesch W, Herrmann CS, Bauml KH. Prestimulus oscillations predict visual perception performance between and within subjects. NeuroImage. 2007;37(4):1465–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser C, Petkov CI, Logothetis NK. Visual modulation of neurons in auditory cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18(7):1560–1574. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil J, Muller N, Ihssen N, Weisz N. On the variability of the McGurk effect: audiovisual integration depends on prestimulus brain states. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(1):221–231. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos P, Chen CM, O’Connell MN, Mills A, Schroeder CE. Neuronal oscillations and multisensory interaction in primary auditory cortex. Neuron. 2007;53(2):279–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos P, O’Connell MN, Barczak A, Mills A, JzVitt DC, Schroeder CE. The leading sense: supramodal control of neurophysiological context by attention. Neuron. 2009;64(3):419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Van Quyen M, Bragin A. Analysis of dynamic brain oscillations: methodological advances. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(7):365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathewson KE, Gratton G, Fabiani M, Beck DM, Ro T. To see or not to see: prestimulus alpha phase predicts visual awareness. J Neurosci. 2009;29(9):2725–2732. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3963-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naue N, Rach S, Struber D, Huster RJ, Zaehle T, Korner U, Herrmann CS. Auditory event-related response in visual cortex modulates subsequent visual responses in humans. J Neurosci. 2011;31(21):7729–7736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1076-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Marqui RD, Michel CM, Lehmann D. Low resolution electromagnetic tomography: a new method for localizing electrical activity in the brain. Int J Psychophysiol. 1994;18(1):49–65. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(84)90014-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romei V, Gross J, Thut G. On the role of prestimulus alpha rhythms over occipito-parietal areas in visual input regulation: correlation or causation? J Neurosci. 2010;30(25):8692–9697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0160-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakowitz OW, Quian Quiroga R, Schurmann M, Basar E. Spatio-temporal frequency characteristics of intersensory components in audiovisually evoked potentials. Cogn Brain Res. 2005;23(2–3):316–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder C, Lakatos P, Kajikawa Y. Neuronal oscillations and visual amplification of speech. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12(3):106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senkowski D, Molholm S, Gomez-Ramirez M, Foxe JJ. Oscillatory beta activity predicts response speed during a multisensory audiovisual reaction time task: a high-density electrical mapping study. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(11):1556–1565. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senkowski D, Gomez-Ramirez M, Lakatos P, Wylie GR, Molholm S, Schroeder CE, Foxe JJ. Multisensory processing and oscillatory activity: analyzing non-linear electrophysiological measures in humans and simians. Exp Brain Res. 2007;177(2):184–195. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senkowski D, Schneider TR, Foxe JJ, Engel AK. Crossmodal binding through neural coherence: implications for multisensory processing. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(8):401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JV, Hunkin NM, Porrill J, Wood R, Keeler V, Beanland M, Port M, Porter NR. When is now? Perception of simultaneity. Proc Biol Sci. 2001;268(1462):31–38. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne JD, De Vos M, Viola FC, Debener S. Cross-modal phase reset predicts auditory task performance in humans. J Neurosci. 2011;31(10):3853–3861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6176-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrence C, Compo GP. A practical guide to wavelet analysis. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 1998;79(1):61–78. doi: 10.1175/1520-0477(1998)079<0061:APGTWA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- VanRullen R, Koch C. Is perception discrete or continuous? Trends Cogn Sci. 2003;7(5):207–213. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanRullen R, Reddy L, Koch C. The continuous wagon wheel illusion is associated with changes in electroencephalogram power at approximately 13 Hz. J Neurosci. 2006;26(2):502–507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4654-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vroomen J, Keetels M. Perception of intersensory synchrony: a tutorial review. Atten Percept Psychophys. 2010;72(4):871–884. doi: 10.3758/APP.72.4.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods D. The component structure of the N1 wave of the human auditory evoked potential. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;44:102–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampini M, Guest S, Shore DI, Spence C. Audio-visual simultaneity judgments. Percept Psychophys. 2005;67(3):531–544. doi: 10.3758/BF03193329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]