Abstract

Rationale

Thousands of mutations across more than 50 genes have been implicated in inherited cardiomyopathies. However, options for sequencing this rapidly evolving gene set are limited as many sequencing services and off-the-shelf kits suffer from slow turnaround, inefficient capture of genomic DNA, and/or high cost. Furthermore, customization of these assays to cover emerging targets and to suit individual needs is often expensive and time-consuming.

Objective

We sought to develop a custom high throughput, clinical-grade next generation sequencing (NGS) assay for detecting cardiac disease gene mutations with improved accuracy, flexibility, turnaround, and cost.

Methods and Results

We employed double-stranded probes (complementary long “padlock” probes (cLPPs)), an inexpensive and customizable capture technology, to efficiently capture and amplify the entire coding region and flanking intronic and regulatory sequences of 88 genes and 40 microRNAs (miRNA) associated with inherited cardiomyopathies, congenital heart disease (CHD), and cardiac development. Multiplexing 11 samples per sequencing run resulted in a mean base coverage of 420, of which 97% had >20× coverage and >99% were concordant with known heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The assay correctly detected germline variants in 24 individuals and revealed several polymorphic regions in miR-499. Total run time was three days at an approximate cost of $100 per sample.

Conclusions

Accurate, high throughput detection of mutations across numerous cardiac genes is achievable with cLPP technology. Moreover, this format allows facile insertion of additional probes as more cardiomyopathy and CHD genes are discovered, giving researchers a powerful new tool for DNA mutation detection and discovery.

Keywords: Next generation sequencing, cardiomyopathies, cardiovascular diseases, complementary long padlock probes, genetic heart disease, genetic testing, congenital heart disease

INTRODUCTION

Historically, the diagnoses of cardiomyopathies and congenital heart disease (CHD) have relied on morphological and functional findings. More recently, molecular genetic determinants of cardiac disease are increasingly complementing these traditional algorithms, and which can also be used for genetic screening of at-risk family members1–6. Thousands of mutations across tens, if not hundreds, of genes have been reported to cause cardiomyopathies or CHD, highlighting the need for logistically feasible diagnostics that address phenotypes across the spectrum of clinical disease.

No single option for cardiovascular genetic testing is ideal for either clinical or research applications (Table 1). Although whole genome sequencing (WGS) is the most comprehensive option and covers genome-wide coding and noncoding regions while benefiting from relatively straightforward sample preparation, WGS incurs expensive sequencing costs and major computational power in order to align and interpret the resulting raw data7. In contrast, whole exome sequencing (WES) reduces cost by targeting only coding regions of the genome (the exome), which are estimated to comprise approximately 1–2% of the genome and yet contain 85% of disease-causing mutations8. However, in order to reliably and selectively target all ~25,000 human genes, WES requires in solution hybridization enrichment strategies that are often inadequate for ensuring consistent high quality coverage across genes. In fact, current estimates of exome coverage through NGS are only between 90 and 95%7, 9, and thus WES may miss important disease-associated genomic regions. Finally, while WES sequence data is less cumbersome than WGS data, it may still be too complex to interpret accurately and efficiently for the typical cardiovascular laboratory.

Table 1.

Options for genetic testing of cardiomyopathy- and CHD-associated genes.

| Method | Number of genes |

Example vendors |

Service available? |

Approx. cost per sample |

Technical Accuracy and Precision |

Data Analysis |

Turn around time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGS or WES | Entire genome or exome | Illumina, Complete Genomics, Macrogen, others | Yes | $1000 – 15000 | Good (WGS), Inconsistent (WES) | Difficult | Weeks to months |

| Cardiac gene panels in CLIA-approved labs | 1–150 (custom panels not available) | GeneDX, Ambry Genetics, Labcorp, ARUP, others | Yes | $1000 – 5000 | Excellent | Included in service | Weeks to months |

| Cardiac gene panel kits | 30–50 (custom panels available at additional cost) | Illumina, Agilent, others | No | >$300 | Varies depending on panel kit performance | Can be difficult for novice users | <1 week |

| cLPP gene panel | Unlimited (fully customizable) | N/A | No | $100 | Excellent | Can be difficult for novice users | 3 days |

Alternatively, disease-targeted NGS panels interrogate a limited set of known disease-associated genes, allowing for greater depth of coverage with increased analytical sensitivity and specificity7. Because the genes targeted in disease NGS panels are already known to be associated with particular diseases, the interpretation of the resulting sequence data is both faster and simpler than WGS and WES. Unfortunately, disease-targeted NGS panels are currently limited to industry-supplied kits or services that are both expensive and inflexible due to the difficulty in adding/removing target regions. Thus, these offerings may not reflect the most up-to-date knowledge of cardiovascular disease-associated genetics, making their utility to researchers limited.

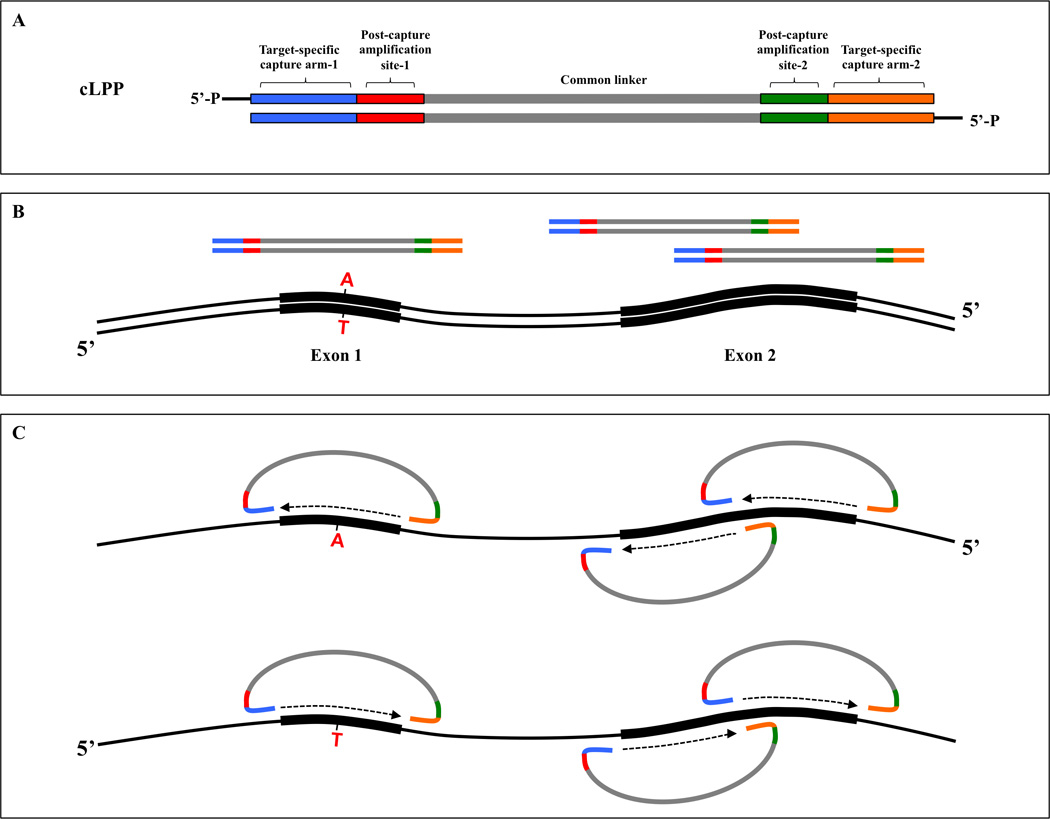

To address these challenges, we have developed a technology termed complementary long padlock probe (cLPP) that utilizes physically tethered amplification primers to rapidly capture and amplify thousands of targets in a single reaction at extremely high specificity and efficiency (Figure 1)10–12. Moreover, because these probes are manufactured through a simple PCR reaction, this technique can by applied at a fraction of the cost of traditional library preparation technologies. The simplicity of this technology allows any researcher the flexibility to add or remove genomic targets at their discretion, and avoids industry kits and services.

Figure 1. Probe target capture with cLPPs.

(A) Each cLPP contains a common linker flanked by post-capture amplification sites (red and green) and two target-specific capturing arms (blue and orange). Probe ends are 5’-phosphorylated to produce functional cLPPs. (B) Schematic of double-stranded genomic DNA (black) with two exons and three cLPPs. Exon 1 is smaller and sufficiently covered by a single cLPP while Exon 2 is larger and requires two cLPPs. A hypothetical point mutation is depicted in Exon 1. (C) Multiplex probe-target hybridization followed by gap-filling and ligation triggers probe circularization and target capture. In contrast to single-stranded probes, double-stranded cLPPs consist of two single-stranded complementary long padlock probes that can capture both strands of a genomic target, thus increasing sensitivity for variant detection.

In this report, we describe the design, construction, and validation of a cardiomyopathy/CHD NGS gene assay that targets 128 genes and miRNAs using cLPPs. Multiplexing 11 samples per sequencing run resulted in a mean base coverage of 420, of which 97% had >20× coverage and >99% were concordant with known heterozygous SNPs. In addition to providing robust analytical performance compared to other modalities such as WES, this platform is also cost-effective, rapid, scalable, and easily adaptable to emerging clinical targets.

METHODS

Patient recruitment

Patient genetic testing for this study was approved by Stanford University Institutional Review Board. We recruited 22 patients from our cardiovascular disease clinics, including two cardiomyopathy families12, 13 (Families 1 and 2) with known DNA mutations or variants. Genomic DNA was isolated using DNeasy Blood and Tissue kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, US). Additionally, genomic DNA from seven members of a third cardiomyopathy family (Family 3) with known DNA variant profiles was acquired from the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute Biobank. Seven HapMap DNA samples were obtained from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ, USA).

Padlock NGS

The protocol of cLPP construction, multiplex target capture, sequence library construction, and sequencing was described previously12 (see also Online Detailed Methods). In brief, oligonucleotide primers containing MlyI (forward primer) and/or BsaI (reverse primer) sites at their 5’ ends, genomic target sequences (18 to 28 bp) in the middle, and bacteriophage lambda sequences at 3’ ends, were used to amplify the probes’ common spacer backbone of approximately 280 bp from bacteriophage lambda DNA. We generated 3,410 individual PCRs of approximately 350 bp in order to target all protein coding sequences, flanking intronic regions, and relevant regulatory regions of target genes and pre-microRNAs (target size range 350 to 425 bp). Multiplex probe-target hybridization followed by gap-filling and ligation triggers probe circularization and target capture. The circularized DNA molecules with captured targets are then multiplex-amplified using custom-designed universal primer pairs directed at the probes’ common backbone, which also included Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) sequencing adapters attached at the ends of these primers. Multiple indexed samples were pooled in equal amounts for 251 bp paired-end MiSeq sequencing. Total time for library construction was approximately four hours. The entire assay time from capture to sequencing start was approximately eight hours.

Sequence read processing and single nucleotide variant calling

Raw fastq read sequences were de-multiplexed and cLPP sequences trimmed from the beginning of each read. We used MiSeq Reporter's Resequencing workflow to align reads to the human genome reference sequence (hg19) in order to obtain the variant call format (VCF) file for each sample. Mapping quality (MAPQ) filtering was set at 30.

Whole exome sequencing

Exome libraries were prepared for the seven-member Family 3 using the Ion AmpliSeq Exome RDY Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Life Technologies, Publication number: MAN0010084) then sequenced on the Ion Proton platform (Life Technologies). Additionally, we obtained five publically available WES VCF files from Illumina BioSpace for four HapMap samples: NA12878 (both Illumina HiSeq 2500 and 4000 platforms), NA12891, NA12892 and NA18507.

Comparison of padlock NGS with WES

The platforms’ variant results were normalized for each sample by analyzing only exonic regions of the 88 target genes, followed by removal of DNA variants that did not pass filter in both the WES and padlock NGS VCF files. Variants with depth of coverage less than 20 reads and/or frequencies less than 0.20 in both WES and padlock NGS were also removed. In total, data from 12 unique exomes using three different sequencing platforms (Ion Proton, HiSeq 2500 and HiSeq 4000) were compared to padlock NGS data for 11 unique individuals.

RESULTS

For the padlock NGS assay, we designed and generated 3,410 individual cLPPs that collectively target all exons, flanking intronic regions, and relevant regulatory regions of 88 target genes associated with cardiomyopathies2, 4, 5, 13 and CHD14–18 (Online Tables I; II and Online Figure I). Genes implicated in syndromes for which clinical diagnosis may be challenging were also included, such as CHD7 (CHARGE syndrome), SURF1 (Leigh syndrome), TBX5 (Holt-Oram syndrome), and RAF1/PTPN11 (Noonan and LEOPARD syndromes). Additionally, we targeted 40 precursor miRNAs (“pre-miRNA”), which are mature miRNA plus flanking RNA processing regions that have been associated with cardiovascular development and disease19. Recent evidence suggests that germline mutations in regions encoding precursor miRNAs may have important cardiac ramifications20–22. Online Table III lists all cLPP primer sequences, genomic target coordinates, and associated amplicon lengths for the assay’s targeted genes and pre-miRNAs. The target amplicon sizes ranged from 350 to 425 bp, and primer binding sites were selected such that they contained no SNPs with mean allele frequency (MAF) greater than 0.05.

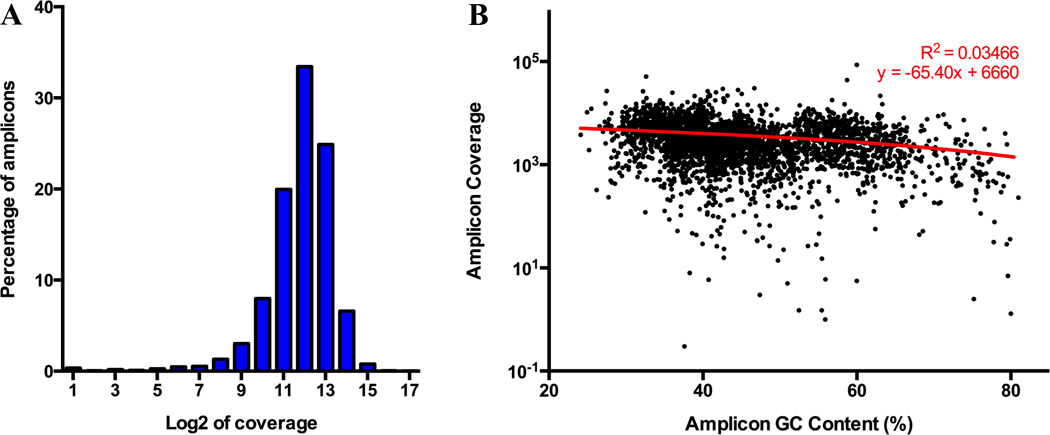

A summary of the assay’s performance metrics is shown in Table 2 and Figure 2 (see also Online Figure II). Multiplexing 11 samples per Illumina MiSeq sequencing run resulted in a mean base coverage of 420, of which 97% had >20× coverage (Table 2). Coverage uniformity was excellent as 95% of cLPP capture products distributed within a 50-fold range (Figure 2A). GC-rich regions, such as CpG islands, are particularly prone to low depth of coverage partly because these regions remain annealed during amplification23. To address this issue, cLPPs were balanced in our assay such that additional cLPPs targeting high GC regions were added to the pool in order to increase their concentration. Thus, the overall depth of coverage obtained by the padlock NGS assay was only minimally affected by GC content (Figure 2B). Greater than 99% of the heterozygous variants detected by padlock NGS for five HapMap samples were concordant with the variant profiles reported by the International HapMap Project for these same samples (Online Table IV). The entire assay time from cLPP multiplex capture of DNA targets to sequencing start was approximately eight hours and the subsequent Illumina MiSeq 2×251 bp sequencing time was 43 hours, resulting in a total run time of approximately three days. The total material cost estimate per sample was $100 ($10 for cLPP target capture and $90 for sequencing). Note that this cost does not include the fixed cost of the NGS instrument itself, which may be prohibitively expensive for individual laboratories to acquire and thus utilization of a core NGS facility would be more cost-effective. Also, this cost does not include bioinformatics personnel support or site-license software that may be needed for data interpretation, depending on the experience of the laboratory. Because of these additional factors, laboratories without prior NGS experience may find the padlock NGS assay, even with its significant cost reduction, to be too challenging to implement on their own without assistance from other laboratories or core facilities.

Table 2.

Padlock assay genomic target and sequencing performance metrics.

| No. of targets | 88 genes + 40 pre-miRNAs |

|---|---|

| Targeted bases | 1.15 M |

| No. of probes (amplicons) | 3410 |

| Target (amplicon) size | 350–425 bp |

| No. of samples per MiSeq run, 2×251bp | 11 |

| % reads align to hg19 | 95% |

| % reads align in target region | 90% |

| Sample mean base coverage | 420 |

| % bases >20× base coverage | 97% |

| % bases >0.2× mean | 87% |

| Concordance of Het SNPs at >20× coverage | 99.70% |

Note the concordance of heterozygous SNPs (bottom row) was determined using the known SNP profiles for five HapMap samples (see Online Table IV).

Figure 2. Coverage uniformity for cLPP capture.

(A) Distribution of log base 2 coverage for 3,410 amplicons captured using cLPPs. Each bar represents a two-fold difference in coverage. Overall, 95% of cLPP capture products are distributed within a 50-fold range (96% within 100-fold). (B) Padlock NGS assay is only minimally affected by amplicon GC content. Each dot represents one amplicon (3,410 total). Best-fit linear regression shows weak correlation (R square 0.03466), indicating that the relationship between amplicon coverage and GC content is negligible.

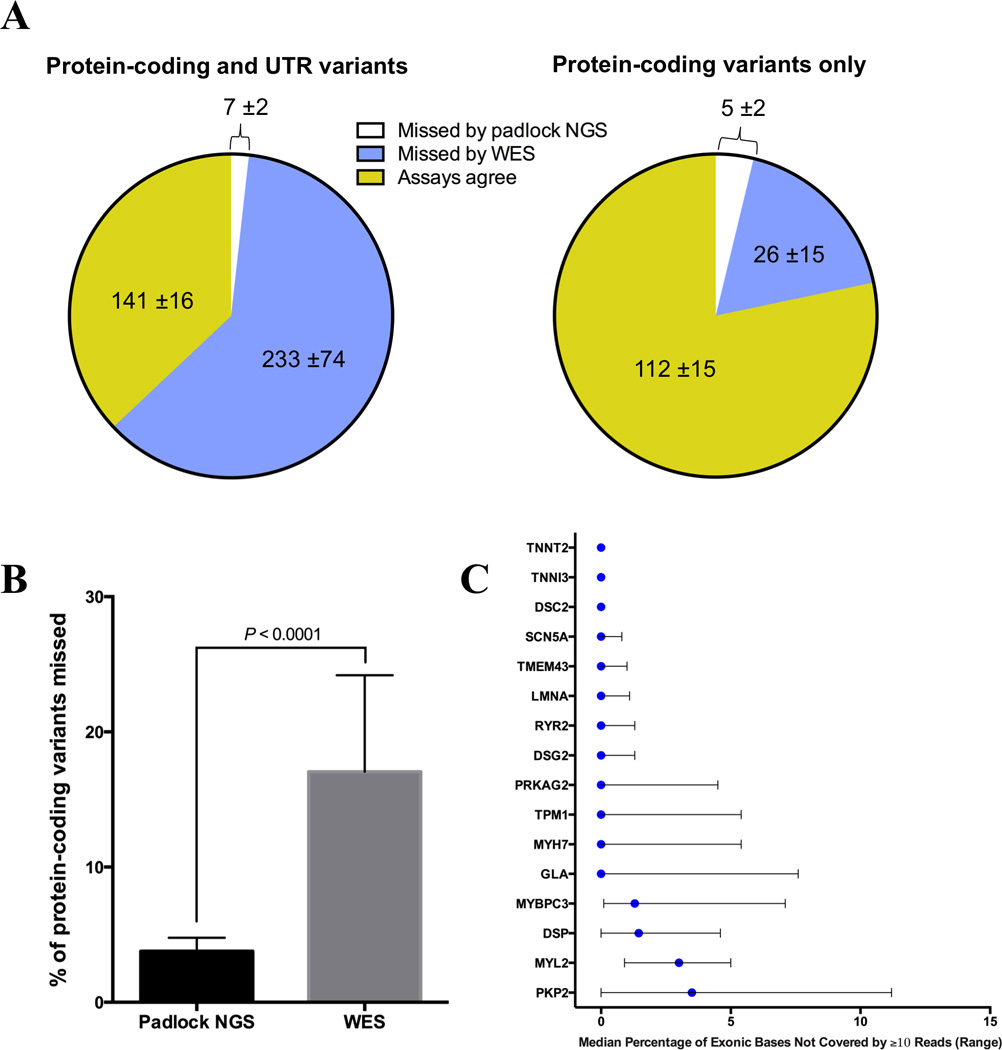

Using data from 12 exomes that were sequenced on multiple platforms (Illumina HiSeq, Ion Proton), we determined that the padlock NGS assay detected significantly more protein-coding variants in the target 88 cardiomyopathy and CHD genes compared to WES (Figure 3 and Online Table V). Furthermore, many WES kits do not capture exonic untranslated regions (UTRs) that have known disease mutations24, including mutations implicated in CHD25 and cardiomyopathy26. The padlock NGS assay, which includes UTRs in its target regions, thus provides a much richer dataset for mutation detection (Figure 3A). Of the 88 genes in the assay, 16 are ACMG-reportable27 and have high clinical value. Using a threshold of 10 reads per base, a typical cutoff used by laboratories for detecting germline heterozygous variants7, at least 96.5% (median) of exonic bases in all 16 ACMG genes were sufficiently covered (Figure 3C), with the majority of genes (12 of 16) demonstrating 100% median coverage. These results are similar to or better than what has been previously reported for ACMG-reportable genes using WGS28. In the future, probe rebalancing to account for increased GC content will further improve these results.

Figure 3. Padlock NGS captures more exonic variants in cardiomyopathy and CHD genes compared to WES.

(A) Detection of protein-coding and UTR variants within 88 target genes by WES and padlock NGS. Pie charts depict mean number (± standard deviation) of variants detected or missed by WES and padlock NGS. Results are from 12 WES/padlock comparisons (see Online Table V). Padlock NGS misses fewer exonic variants, particularly in UTR regions, than WES. (B) Padlock NGS misses a smaller percentage of protein-coding variants in target genes compared to WES (mean 3.8% vs. 17.1%, respectively). Percent was calculated by dividing the number of missed variants by the total combined number detected by both padlock NGS and WES for each sample. Error bars show standard deviation. (C) Exonic base coverage for 16 ACMG-reportable genes included in the padlock NGS assay. Graph summarizes the data from 32 unique sequence runs of 27 unique samples. Blue circles indicate the median percentage of exonic bases not covered by a minimum of 10 reads, and black bars indicate the range across all sample runs. These results are similar to or better than what has been previously reported for ACMG-reportable genes using WGS28. 12 of the 16 genes achieved 100% coverage, while the remaining four (MYBPC3, DSP, MYL2 and PKP2) exhibited some loss of coverage, likely due to high GC content in target regions. In the future, probe rebalancing to account for increased GC content can further improve these results.

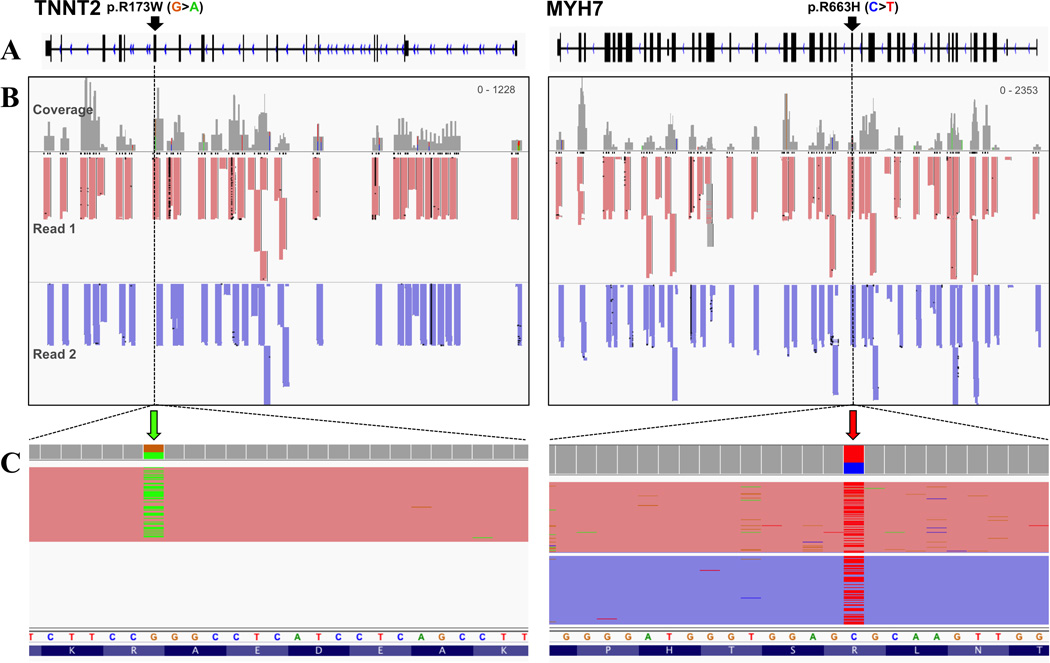

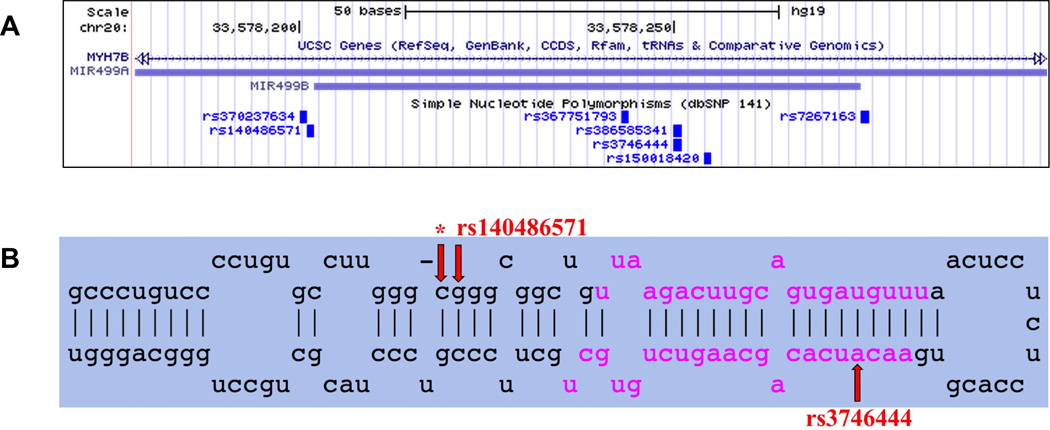

Importantly, the assay successfully detected 15 unique DNA variants across 11 genes in 24 positive control individuals (Table 3). Examples of heterozygous mutations that were detected in two individuals are shown in Figure 4. Lastly, the pre-miRNA sequencing results revealed that pre-miR-499 is a relative hotspot for variants in our sample population (Figure 5), though we did not detect known mutations in the mature miR-499 (miR-499-5p) as has been previously reported20. We did detect a novel nucleotide change in pre-miR-499 (g.33578201 C>T) in sample LMNA-5 that has not been previously described, but it is likely benign since this individual is reported to be healthy.

Table 3.

Genomic DNA samples sequenced with padlock NGS assay.

| Sample ID | Relationship | Disease | Reported disease variant(s) |

Padlock NGS correctly detected? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYH7-1 | Mother* | HCM | MYH7 p.R663H | Yes |

| MYH7-2 | Father* | None | None | Yes |

| MYH7-3 | Son* | HCM | MYH7 p.R663H | Yes |

| MYH7-4 | Son* | None | MYH7 p.R663H | Yes |

| MYH7-5 | Son* | None | MYH7 p.R663H | Yes |

| MYH7-6 | Son* | None | None | Yes |

| LMNA-1 | Sister† | AF/DCM | LMNA p.K117fs | Yes |

| LMNA-2 | Sister† | AF/DCM | LMNA p.K117fs | Yes |

| LMNA-3 | Cousin† | AF/DCM | LMNA p.K117fs | Yes |

| LMNA-4 | Cousin† | AF/DCM | LMNA p.K117fs | Yes |

| LMNA-5 | Cousin† | None | None | Yes |

| LMNA-6 | Cousin† | None | None | Yes |

| 1008 | Son‡ | HCM |

CRYAB p.P51L TPM1 p.K37E |

Yes |

| 1009 | Son‡ | None | TTN p.G12895R | Yes |

| 1010 | Son‡ | HCM |

CRYAB p.P51L, TPM1 p.K37E TTN p.G12895R |

Yes |

| 1012 | Uncle‡ | None | TTN p.G12895R | Yes |

| 1015 | Cousin‡ | None | None | Yes |

| 1018 | Father‡ | None | CRYAB p.P51L | Yes |

| 1019 | Mother‡ | HCM |

TPM1 p.K37E TTN p.G12895R |

Yes |

| TNNT2 | NA | DCM | TNNT2 p.R173W | Yes |

| MYH7-R | NA | HCM | MYH7 p.R403Q | Yes |

| 10860 | NA | HCM | MYBPC3 p.W890X | Yes |

| 6350Q | NA | DCM | PLN p.R9C | Yes |

| IK | NA | HCM | MYBPC3 p.R943X | Yes |

| 1141Q1 | NA | HCM | PRKAG2 p.A44T | Yes |

| 6437N1 | NA | DCM | DES p.L136H | Yes |

| 2946N1 | NA | DCM | TPM1 p.T282S | Yes |

| 9196N1 | NA | HCM | MYBPC3 p.S137X | Yes |

| RW | NA | HCM | NEXN p.E332A | Yes |

| NA12891 | HapMap | None | None | Yes |

| NA12892 | HapMap | None | None | Yes |

| NA11840 | HapMap | None | None | Yes |

| NA19625 | HapMap | None | None | Yes |

| NA12156 | HapMap | None | None | Yes |

| NA12878 | HapMap | None | None | Yes |

| NA18507 | HapMap | None | None | Yes |

36 patient and HapMap samples were analyzed in a blinded fashion.

First family;

Second family;

Third Family;

NA=not applicable (no familial relationship). DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; AF, atrial fibrillation.

Figure 4. Padlock NGS assay mutation detection in two individuals.

Schematics of the genomic regions for TNNT2 (left) and MYH7 (right). (A) Exon/intron distribution for each gene with the mutation positions (black arrows) shown in samples TNNT2 and MYH7-1 (see Table 3). (B) Read coverage after paired-end sequencing. Read 1 (red) and Read 2 (purple) in both samples illustrate the specificity of padlock probe amplicon amplification. (C) Detection of the DNA mutation in each sample (colored arrows in zoom view). Note that TNNT2 p.R173W was detected in Read 1 only, while MYH7 p.R663H was detected in both reads due to overlap in coverage. Nucleotides are colored as follows: G=orange, A=green, C=blue, T=red.

Figure 5. Three DNA variants detected in pre-miR-499.

(A) UCSC Genome Browser screenshot of genomic locations for pre-miR-499a, pre-miR-499b, and associated SNPs. Both miRNAs are located in an intron of the gene MYH7B. (B) miRBase34 screenshot of miR-499a stem-loop precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA), which is further cleaved by the cytoplasmic Dicer ribonuclease to generate the mature miRNA (-5p) and antisense miRNA star products (-3p) (pink nucleotides). rs3746444 (MAF 18.35%, g.33578251 A>G) was detected in 13 DNA samples, and rs140486571 (MAF 0.12%, g.33578202 G>A) detected in one DNA sample (2946N1). Although rs3746444 is located in miR-499–3p, the complement to mature miR-499–5p, miR-499-3p is degraded during processing and so has no known biological effect on the heart20. *Indicates a novel nucleotide change detected at this position (g.33578201 C>T) in sample LMNA-5; it is likely benign. MAF, minor allele frequency (calculated from 1000 Genome phase 1 genotype data).

DISCUSSION

Current diagnostic assays for cardiomyopathies and CHD are limited by technical performance, expense, and turnaround time. Here, we describe a cLPP-based approach that yields accurate, high throughput detection of mutations across numerous cardiac genes. Both inexpensive and rapid, this padlock NGS assay can be immediately utilized as a research use only tool for cardiovascular gene mutation discovery, or transitioned to a CLIA-certified clinical laboratory for clinical diagnostic testing after appropriate validation. Moreover, due to cLPPs’ relative lack of probe-probe interaction, insertion of additional probes into the pool as more cardiomyopathy-related genes are discovered is easily achievable, giving researchers a flexible platform for DNA mutation detection.

In general, a major consideration for cardiovascular researchers interested in genetics of disease is whether to sequence their samples using a broad approach (WGS, WES) or more focused approach (disease-specific panels). Clearly, WGS is the gold standard for genome sequencing because it enables global quantification of all variant types (SNPs, insertion-deletions, structural variants such as genomic rearrangements, and copy number variation) in both the minority of the human genome that encodes proteins and the remaining majority of non-coding sequences23, 29. However, the computational power required for aligning and storing WGS sequence reads, not to mention the difficulty in interpreting the numerous DNA variants in the resulting data28, 30, are currently a significant impediment to widespread adoption of WGS.

One option that reduces genome sequencing complexity and cost is WES, which focuses on protein-coding genes while omitting most noncoding regions23. Interestingly, the drop in cost to the $1,000 human genome31 has rendered the sequencing costs for both WGS and WES roughly equivalent29. However, when taking into account the computation-intensive nature of WGS data, the cost reductions associated with WES becomes significantly more attractive29. WES does have technical limitations that cannot be discounted. Differences in the hybridization efficiency of sequence capture probes due to GC content may result in target regions with little or no coverage, and hybridization capture technologies often perform poorly in target regions that bear low complexity or sequence similarity to other regions of the genome. Our analysis of WES data reinforces these concerns, as we found that over 17% of protein-coding variants in cardiomyopathy and CHD genes were on average insufficiently detected. The poor sensitivity of WES should be a consideration for researchers interested in genetic testing of cardiac diseases.

In contrast to global-scale methods such as WGS and WES, disease-targeted gene panels limit sequencing to known disease-associated genes, resulting in more manageable data and storage requirements. Overall, targeted NGS panels focus on clinically actionable genes at higher quality, lower cost, and increased analytical sensitivity and specificity7. Laboratories are also able to use smaller and cheaper sequencing instruments (e.g., Illumina MiSeq vs. HiSeq) and sequence more samples per run compared to WES and WGS7. However, though disease-targeted NGS panels have many positive attributes, unfortunately many are offered only as expensive, inflexible services or kits that may not be easily customized to individual needs.

To address these issues, we sought to use cLPPs that would allow for customizable, inexpensive, rapid, and highly accurate targeted sequencing of cardiomyopathy- and CHD-associated genes and pre-miRNAs. Many target enrichment technologies utilize single-stranded oligonucleotide probes to capture genomic regions before sequencing. In contrast, double-stranded cLPPs, which consist of single-stranded, complementary long padlock probes, capture both strands of a genomic target, thus increasing sensitivity for variant detection12. Because of the large capture lengths that are possible with cLPPs, most human exons can be covered using a single probe, making sequencing more economical. Furthermore, cLPPs’ DNA capture length can be adjusted to the length of the NGS read, which allows for maximization of increasingly longer sequence reads. As with many enrichment strategies, probe:DNA hybridization kinetics can be optimized by redesigning failed probes using new design algorithms such as reducing GC content of hard-to-capture targets, and avoiding common SNPs in probes’ annealing regions12, 32.

The field of cardiovascular genetics is constantly evolving as new disease-associated genomic targets are seemingly reported each month. In order to adapt to these exciting advancements, a flexible platform for detecting mutations is needed that can be continuously improved by as many qualified users as possible. As with the introduction of “open source” computer operating systems such as Linux that allow users to modify and distribute the underlying source code, we believe a similar development is needed in the arena of genetic testing33. In publishing the cLPP primer sequences and genomic target locations, which can be reproduced, customized and expanded by anyone, this padlock NGS assay is therefore the first step in this direction.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Thousands of DNA mutations across more than 50 genes have been implicated in cardiomyopathies and congenital heart disease (CHD).

Options for detecting these mutations are limited as many commercial services and off-the-shelf kits suffer from slow turnaround, inaccuracy, and/or high cost.

Furthermore, customization of these assays to include newly discovered heart disease-associated genes is often expensive and time-consuming.

What New Information Does This Articles Contribute?

We developed a custom assay for detecting genetic variants in genes implicated in hereditary cardiac diseases with improved accuracy, flexibility, turnaround, and cost.

The assay targets known cardiomyopathy- and CHD-associated genes using a novel DNA probe technology termed “complementary long padlock probes” (cLPPs).

Moreover, this assay format allows inclusion of additional probes as more disease-related genes are discovered.

Molecular genetic studies are increasingly complementing traditional morphological and functional findings to diagnose cardiac disease, and can also be used for genetic screening of at-risk family members. Thousands of mutations across tens, if not hundreds, of genes have been reported to cause cardiomyopathies or CHD, highlighting the need for logistically feasible diagnostics that can be used complement the phenotypic diagnosis across the spectrum of disease. Currently, diagnostic genetic assays are limited by technical performance, expense, and turnaround time. To address this need, we employed an inexpensive and customizable DNA probe technology, cLPPs, to efficiently sequence 88 genes and 40 microRNAs associated with cardiomyopathies and CHD. In our validation studies, the cLPP assay correctly detected DNA mutations in 24 individuals with a run time of only three days and at an approximate cost of $100 per sample. Compared to other approaches, the cLPP assay exhibited greater accuracy and detected significantly more DNA variants in target genes. Both inexpensive and rapid, the cLPP assay can be utilized as a research use tool or transitioned to a clinical laboratory for diagnostic testing after appropriate validation. Moreover, inclusion of additional probes as more disease-related genes are discovered is easily achievable, giving researchers a flexible platform for DNA mutation detection.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was in part supported by NIH R01 HD081355 (CS), Stanford Cardiovascular Institute Seed Grant (CS, KDW), the Steven M. Gootter Foundation (CS, KDW), AHA 13EIA14420025 (JCW), NIH R01 HL126527 (JCW), NIH R01 HL113006 (JCW), and NIH R24 HL117756 (JCW). We are offering aliquots of our cardiomyopathy/CHD cLPP assay free of charge upon request.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ACMG

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- Bp

base pair

- CHD

congenital heart disease

- cLPP

complementary long padlock probe

- DCM

dilated cardiomyopathy

- HCM

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- MAF

mean allele frequency

- miRNA

microRNA

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- UTR

untranslated region

- VCF

variant call format

- VUS

variant of unknown significance

- WES

whole exome sequencing

- WGS

whole genome sequencing

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fox CS, Hall JL, Arnett DK, et al. Future translational applications from the contemporary genomics era: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:1715–1736. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norton N, Li D, Hershberger RE. Next-generation sequencing to identify genetic causes of cardiomyopathies. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2012;27:214–220. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328352207e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rehm HL. Disease-targeted sequencing: a cornerstone in the clinic. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nrg3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teekakirikul P, Kelly MA, Rehm HL, Lakdawala NK, Funke BH. Inherited cardiomyopathies: molecular genetics and clinical genetic testing in the postgenomic era. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15:158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. Genetic testing for potentially lethal, highly treatable inherited cardiomyopathies/channelopathies in clinical practice. Circulation. 2011;123:1021–1037. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.914838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Churko JM, Mantalas GL, Snyder MP, Wu JC. Overview of high throughput sequencing technologies to elucidate molecular pathways in cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 2013;112:1613–1623. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehm HL, Bale SJ, Bayrak-Toydemir P, Berg JS, Brown KK, Deignan JL, Friez MJ, Funke BH, Hegde MR, Lyon E. ACMG clinical laboratory standards for next-generation sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:733–747. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majewski J, Schwartzentruber J, Lalonde E, Montpetit A, Jabado N. What can exome sequencing do for you? J Med Genet. 2011;48:580–589. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cirulli ET, Singh A, Shianna KV, Ge D, Smith JP, Maia JM, Heinzen EL, Goedert JJ, Goldstein DB. Screening the human exome: a comparison of whole genome and whole transcriptome sequencing. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R57. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-r57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnakumar S, Zheng J, Wilhelmy J, Faham M, Mindrinos M, Davis R. A comprehensive assay for targeted multiplex amplification of human DNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9296–9301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803240105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen P, Wang W, Krishnakumar S, Palm C, Chi AK, Enns GM, Davis RW, Speed TP, Mindrinos MN, Scharfe C. High-quality DNA sequence capture of 524 disease candidate genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6549–6554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018981108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen P, Wang W, Chi AK, Fan Y, Davis RW, Scharfe C. Multiplex target capture with double-stranded DNA probes. Genome Med. 2013;5:50. doi: 10.1186/gm454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopes LR, Zekavati A, Syrris P, Hubank M, Giambartolomei C, Dalageorgou C, Jenkins S, McKenna W, Plagnol V, Elliott PM. Genetic complexity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy revealed by high-throughput sequencing. J Med Genet. 2013;50:228–239. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomita-Mitchell A, Maslen CL, Morris CD, Garg V, Goldmuntz E. GATA4 sequence variants in patients with congenital heart disease. J Med Genet. 2007;44:779–783. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.052183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schott JJ, Benson DW, Basson CT, Pease W, Silberbach GM, Moak JP, Maron BJ, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Congenital heart disease caused by mutations in the transcription factor NKX2-5. Science. 1998;281:108–111. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rauch R, Hofbeck M, Zweier C, Koch A, Zink S, Trautmann U, Hoyer J, Kaulitz R, Singer H, Rauch A. Comprehensive genotype-phenotype analysis in 230 patients with Tetralogy of Fallot. J Med Genet. 2010;47:321–331. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.070391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaidi S, Choi M, Wakimoto H, et al. De novo mutations in histone-modifying genes in congenital heart disease. Nature. 2013;498:220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lan F, Lee AS, Liang P, et al. Abnormal calcium handling properties underlie familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porrello ER. MicroRNAs in cardiac development and regeneration. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013;125:151–166. doi: 10.1042/CS20130011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorn GW, 2nd, Matkovich SJ, Eschenbacher WH, Zhang Y. A human 3' miR-499 mutation alters cardiac mRNA targeting and function. Circ Res. 2012;110:958–967. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.260752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding SL, Wang JX, Jiao JQ, Tu X, Wang Q, Liu F, Li Q, Gao J, Zhou QY, Gu DF, Li PF. A pre-microRNA-149 (miR-149) genetic variation affects miR-149 maturation and its ability to regulate the Puma protein in apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:26865–26877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.440453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohanian M, Humphreys DT, Anderson E, Preiss T, Fatkin D. A heterozygous variant in the human cardiac miR-133 gene, MIR133A2, alters miRNA duplex processing and strand abundance. BMC Genet. 2013;14:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-14-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sims D, Sudbery I, Ilott NE, Heger A, Ponting CP. Sequencing depth and coverage: key considerations in genomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrg3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chatterjee S, Pal JK. Role of 5'- and 3'-untranslated regions of mRNAs in human diseases. Biol Cell. 2009;101:251–262. doi: 10.1042/BC20080104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reamon-Buettner SM, Cho SH, Borlak J. Mutations in the 3'-untranslated region of GATA4 as molecular hotspots for congenital heart disease (CHD) BMC Med Genet. 2007;8:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beffagna G, Occhi G, Nava A, Vitiello L, Ditadi A, Basso C, Bauce B, Carraro G, Thiene G, Towbin JA, Danieli GA, Rampazzo A. Regulatory mutations in transforming growth factor-beta3 gene cause arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 1. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, Kalia SS, Korf BR, Martin CL, McGuire AL, Nussbaum RL, O'Daniel JM, Ormond KE, Rehm HL, Watson MS, Williams MS, Biesecker LG. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:565–574. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dewey FE, Grove ME, Pan C, et al. Clinical interpretation and implications of whole-genome sequencing. JAMA. 2014;311:1035–1045. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meynert AM, Ansari M, FitzPatrick DR, Taylor MS. Variant detection sensitivity and biases in whole genome and exome sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:247. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chrystoja CC, Diamandis EP. Whole genome sequencing as a diagnostic test: challenges and opportunities. Clin Chem. 2014;60:724–733. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.209213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayden EC. Technology: The $1,000 genome. Nature. 2014;507:294–295. doi: 10.1038/507294a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyle EA, O'Roak BJ, Martin BK, Kumar A, Shendure J. MIPgen: optimized modeling and design of molecular inversion probes for targeted resequencing. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2670–2672. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deibel E. Open Genetic Code: an open source in the life sciences. Life Sci Soc Policy. 2014;10 doi: 10.1186/2195-7819-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D68–D73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.